Moving from Introspection to Global Diversity at Sodexo

COMPANY: Sodexo

STAGE: Compliance to sustainable

BEST PRACTICES: Global strategy, local implementation, training, diversity scorecard metrics

KEY QUOTE: “What may have initially been sort of resistance, seeing it as a legal mandate, very soon became an enabler of business growth and business success. We went from that class action legal mandate to more of a business enabler.”—Rohini Anand, PhD, former global CDO, Sodexo

Imagine you land your dream leadership job, CDO, at one of the world’s twenty largest employers, with over 420,000 employees in sixty-four countries. You are prepared to make a difference on a grand scale, empowered to integrate diversity into the professional lives of nearly half a million workers. Then, six months in, there comes an $80 million class action lawsuit that directly falls under your leadership purview.

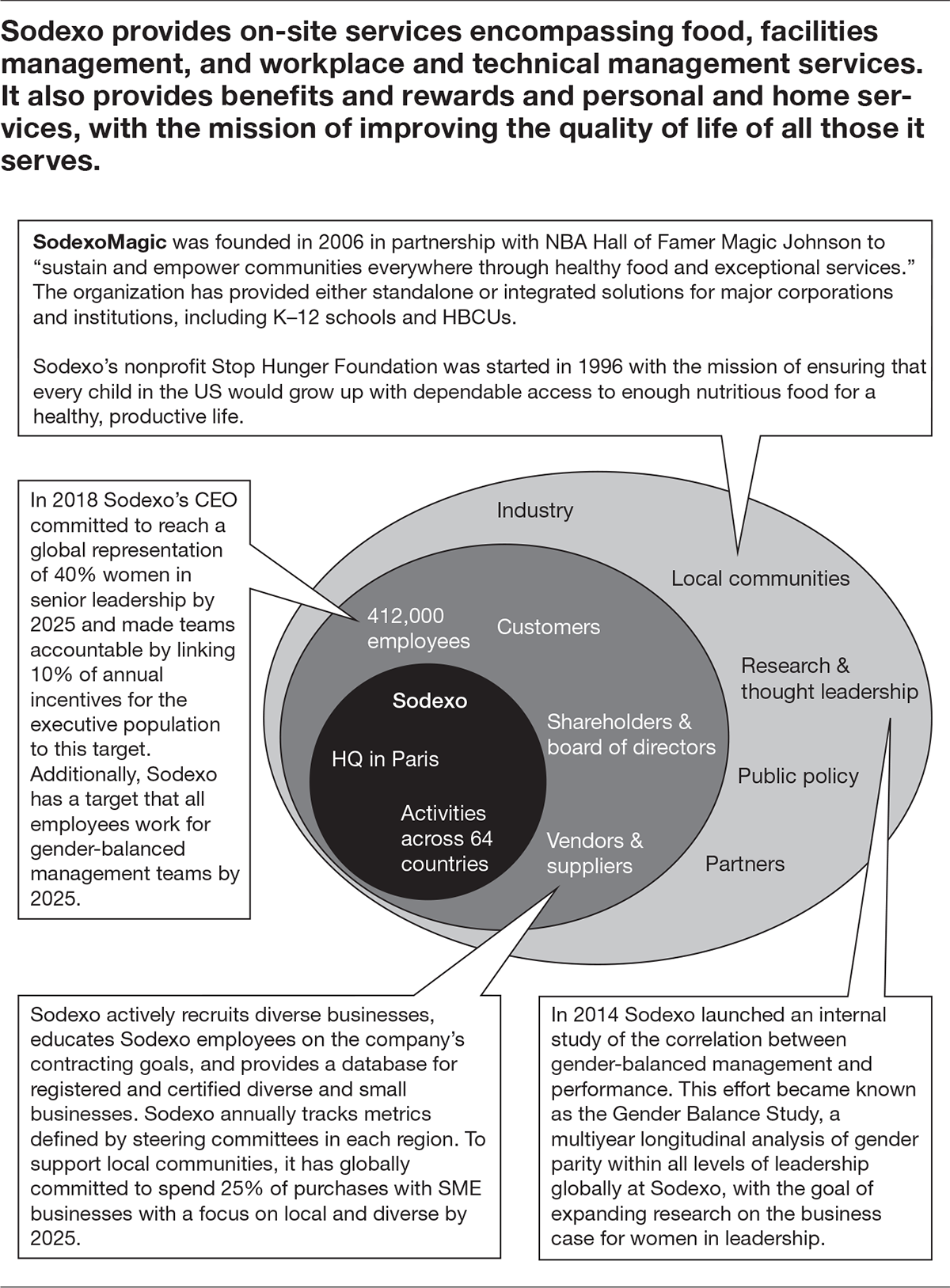

This was the exact experience of Rohini Anand, CDO for Sodexo, a French company specializing in food services and facilities management. The forty-five-year-old company is headquartered in the Paris suburb of Issy-les-Moulineaux. Despite its size, Sodexo is a family business, founded by Pierre Bellon in Marseilles, France, and is still majority family owned today.1

Anand found herself at the company’s forefront during one of the darkest periods for the company. In March 2001 approximately 3,400 of Sodexo’s Black employees filed a class action discrimination lawsuit against their employer, charging that they were routinely barred from promotions and segregated in the company. Of the company’s 100,000-plus North American employees in the year 2000, Black employees held 18 out of 700 upper management jobs and none of the 188 top corporate jobs.2

The company would settle the $80 million suit in 2005; it was the largest race-related job bias settlement of the era. In addition to the monetary settlement, Sodexo denied any wrongdoing through a consent decree, that is, a voluntary agreement between two parties to cease legal activities in exchange for a settlement. The company also agreed to a five-year plan to improve diversity practices. Sodexo agreed to make enhancements to its systems, policies, and practices, including the establishment of an independent panel of monitors for five years to oversee the implementation of the nonmonetary provisions of the decree.

The initial excitement Anand had about her new role was quickly overshadowed by an enormous legal mandate to turn things around quickly, under a watchful eye. As the first CDO ever at the company, she had no playbook for how to build a DEI strategy from the ground up while meeting strict compliance parameters being set by others.

“There really was no roadmap,” she recalled. “I don’t think people knew what to do, or how to make it happen, or where to start, or where to go from step one. There was a lot of resistance because this was seen as a legal thing. It’s one more thing we have to do on top of our day jobs.”

Surprising to Executives, Not to Workers

CEO Michel Landel remembered the shock felt when the lawsuit was disclosed. “It was very painful,” he recalled. “Our culture has been built around strong values and a spirit of service and progress, and the majority of promotions in our company are internal. So, when we were told employees felt that we’d discriminated against them, we were surprised.”3

Leadership’s lack of awareness about employees’ DEI struggles isn’t unusual; I’ve seen it before. In most organizations, a leadership perception gap exists between how executives and managers view the organization’s inclusivity and how employees experience working there. For example, a Gartner survey had these findings:4

- Only 41 percent of employees agree that senior leadership acts in their best interest, compared with 69 percent of executives.

- Only 56 percent of employees agree they feel welcome to express their true feelings at work, compared with 74 percent of executives.

- Only 47 percent of employees believe leadership takes their perspective into consideration when making decisions, whereas 75 percent of senior leaders feel they do.

That is, roughly three-quarters of leaders see their organizations as inclusive, while less than half of workers do. That’s a massive gap that contributes to leaders having no clear sense of what it is like to be in the lower or middle ranks of the organization, especially for employees from different backgrounds. The mere fact that they are leaders contributes to this difference: research on perspective-taking has demonstrated that possessing power itself impedes a person’s ability to understand the perspectives of others.5 Thus, it is not surprising that Sodexo’s mostly White male leadership at the time lacked insight into the experience of Black employees and was shocked by the class action lawsuit.

A typical reaction when leaders are made aware of this gap—not always so dramatically through a class action lawsuit, more typically through an individual incident—is to entrench themselves and defend both themselves and their organizations, especially in public. Anand was pleased that this was not how Sodexo approached it. Instead, the company acknowledged the pain of the moment and used it as a catalyst for change.

“It was quite a rude shock for the company,” she told me. “We had a French CEO at the time. And he was an extremely inclusive, open executive. And this lawsuit was a difficult time for the company.” In an NPR interview, she described one result of the lawsuit: “I think it made us introspective. You never want to feel that there’s even one person in the company who feels they don’t have an opportunity to succeed.”6 Anand again described this sense of introspection when I interviewed her: “It made the company look within and reflect on how we got here and what we needed to do to change.”

The Introspective Process: Acknowledge, Be Open, Be Humble

Any company facing employee backlash and trying to introspectively understand the current DEI landscape must first acknowledge both the structural systems at play and the individual actors who bring the company culture to life. For Sodexo, part of its structural challenges stemmed from the rapid expansion through acquisition.7

“We went from a French company with 25,000 employees to acquiring Marriott Management Services and growing overnight to 125,000 employees,” said Anand. “So, the processes and systems were not as consistent as they should have been. The company was more focused on the basics such as just getting payroll done. The result was a very decentralized organization.”

Although Sodexo was a large company experiencing the challenges of getting the day-to-day tasks done, I also see these challenges with smaller, newer companies not focused on DEI from the beginning because they are just trying to get off the ground. In the early days of building a new company or navigating the transition through an acquisition, organizations must have DEI at the forefront of their vision and build it into their architecture. Otherwise, an organization will more easily end up where Sodexo did, having endured a damaging lawsuit and still having to build its culture of diversity from the ground up.

The second part of introspection involves gaining an understanding of the lived experiences for all levels and backgrounds of employees. Listening and understanding is the only way to reestablish trust in the organization. Anand described some of the challenges she faced as she led the effort to build a culture of trust after the lawsuit. “I’m Asian American,” she said. “I’ve known African Americans, so I was very, very conscious of my identity, and the need to build relationships and trust with the African American community. Obviously, I was aware of discrimination, but I had not experienced what they had experienced with the toxic history of slavery. So, I had to be open to learning, be humble. Instead of coming in with my own agenda, I listened. I had to make a very intentional effort to build those relationships and to build trust.”

Trust in leadership is a major challenge in most organizations, never mind a company facing a suit from its own employees. According to Gallup’s global database, only one in three employees strongly agrees that they trust the leadership of their organization.8 Yet trust is a critical factor in the success of DEI efforts. Without it, diversity practices alone are likely to fail.9

Rebuilding trust after employees have publicly expressed frustration with the DEI climate of an organization is extremely challenging and often takes many years of intentional efforts to repair. Anand discussed how she began this journey in the early years after the lawsuit settlement: “Building trust began with candid conversations. I acknowledged that I did not know but was willing to learn and to listen. It began with admitting that this was an extremely difficult time for the company and that, while we were not perfect, we were committed to trying.”10

After the period of introspection, Sodexo had a clear way to focus its efforts: by earning compliance with the terms of the lawsuit settlement. Compliance would yield meaningful changes in the organization and was clearly laid out. As Anand saw it, the compliance program was a good place to start because the terms were so concrete. They’d provide a foundation. “The consent decree articulated ten different things that we needed to do and was in place until 2010,” she explained. “Those items in the consent decree became very much our baseline.”

Being at the compliance stage does not feel good for any company. The word itself has negative connotations outside the legal field, suggesting it’s the bare minimum to pass—just barely doing enough. However, compliance is where many organizations like Sodexo have started their DEI journey, either through specific legal mandates or more generally to comply with EEOC statutes. At Sodexo, for example, those initial years focused on meeting certain parts of the ten-point plan given to the company by regulators. Specifically, the company focused on designing and implementing companywide processes for talent selection and performance review.

Yet compliance is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be a good starting place for a company without a plan, because it provides so much built-in structure. It gives you goals to hit (the line between being compliant and noncompliant) and provides a kind of focus.

But leaders need to go into this exercise recognizing—indeed, trumpeting—the fact that compliance is not the endgame. It’s the foundation. It’s near the start of the necessary journey, not the destination.

Anand recognized the incomplete nature of compliance and, with CEO Landon, made sure that while they worked on meeting the terms of settlement, they also went further. With the structure of compliance giving a path forward, she focused on quickly growing beyond that.

To that end, the company committed to diversity training, work-life effectiveness programs, mentoring programs, employee network groups, leadership education, awards and recognition, and diversity councils. It also invested in internal and external communication through the company’s website and the annual diversity report.11

A diversity scorecard was implemented to measure progress in increasing diversity in the management ranks and to set targets for women and minorities in leadership positions. Later, it added inclusive behaviors as part of the scoring. This scorecard was innovative for the time in the way it used incentives: 25 percent of the executive team’s bonus and 10 to 15 percent of manager bonuses were tied to performance on the diversity scorecard.

Anand remembered how compliance quickly spurred actions the regulators weren’t mandating. “The first year, we trained five thousand people within the organization on compliance training, what we later called the Spirit of Inclusion,” she said, referring to the mandate. “But after that, action came from accountability [with the diversity scorecard]. The important piece here was that it was a protected bonus. Even if the company didn’t do well financially, that bonus was still paid out. That sent a message that we’re in for the long haul. Accountability is really important. How are we holding the managers and individuals accountable for really showing progress and being clear about what their progress looks like?”

In the first seven years of the implementation of the diversity scorecard, the percentage of minority employees increased by 23 percent, and the number of women employees rose by 11 percent.12 For companies finding themselves in the compliance stage, they should embrace it and then be prepared to grow beyond it by taking the time to understand what the organization desires and needs from DEI to thrive.

“I think the baseline is compliance,” Anand said. “Absolutely critical. But clearly, there needs to be a compelling reason for people to change. So that’s the business case, and it has to be embedded within your core business strategy. Yes, it is about social justice. And it is about [its] being the right thing to do. And we all want to do that. But unless it really is embedded within the mission, the value proposition, and your core business, it’s not going to move beyond that legal and compliance space.”

Chipping Away at Resistance

A first step in moving beyond compliance is to understand how DEI impacts your business. Anand explained it this way:

Engaging a predominantly White male executive team and getting their buy-in was one of my first priorities. They had to overcome their view that DEI was simply a legal requirement and irrelevant to the business. They also had to be convinced that it was a way to attract and engage the best talent. And they had to see DEI as a market differentiator and an enabler of business success if we wanted a truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive organization as an outcome.

To get there, the executives had to take ownership of their own learning journeys. I had to influence these leaders, chipping away at their resistance, so that ultimately, they demonstrated their inclusive leadership.

While engaging the executive team alone is a necessary step, it was only the first step. The next was to look at all systems involved in the talent process and figure out how they were blocking progress or reinforcing bias, or doing both. That required a deep dive and partnering with many groups across a vast organization—a task made more complicated by Sodexo’s recent annexation of a large company in Marriott Management Services.

Consequently, as a new leader, Anand had to build credibility with management and establish a reputation as someone who knew what she was doing and could deliver. She found herself needing to find practical ways to encourage the commitment needed to make the culture more diverse and inclusive while aligning it with the realities of a low-margin business to get the buy-in of senior leaders.

In her book on leading global DEI, Anand describes this journey from compliance to tactical efforts:

With these advances, Sodexo gained stature as a thought leader in DEI. Sodexo’s leadership, who had previously considered DEI merely a legal requirement, now saw it as an asset to the company. The legal requirements became an irrelevant threshold that the company far exceeded as they realized the benefits. When the consent decree monitoring committee expired in 2010, the leadership decided to appoint an external DEI advisory board for several years after to ensure Sodexo continued to remain intentional in addressing DEI and had an external perspective to inform that commitment.13

Leadership’s early efforts started to differentiate Sodexo meaningfully for clients as well. In this way, Sodexo’s DEI strategy matured from compliance to tactical efforts.

Thinking Globally, Acting Locally

Tactically, Sodexo faced even more challenges. It was one thing to absorb 125,000 new employees from the Marriott acquisition (and the attendant systems, processes, and culture that came with them). Sodexo also had to deal with the fact that in the United States alone, the organization was now spread out over twelve thousand locations.

“My concern was, this is such a decentralized organization,” Anand explained. “Our managers work out of client sites, so how are we going to kind of build this inclusive culture?” Fortunately, the decentralization proved to be more of an amplifier than a dampener. “As we started to roll out our initiatives,” she said, “our managers started sharing some of it with their clients. The clients started seeing what we were doing. So then the clients started asking for our expertise and our knowledge.”

In a way, Sodexo’s effort went a bit viral within its complex network of sites. Suddenly, executives saw how the DEI compliance effort was good for business. “That really expedited the engagement across the organization,” Anand said. “What may have initially been sort of resistance on the part of the organization, seeing it as a legal mandate, very soon became an enabler of business growth and business success. We went from that class action legal mandate to more of a business enabler.”

One unique attribute of Sodexo’s DEI journey is its global nature. While the company managed negative perceptions and a significant backlash in the United States because of the class action lawsuit, it also had to build a global DEI strategy for its eighty countries under the strained circumstances.

The challenges of a global DEI strategy are significant. Diversity management requires understanding how each country defines and conceptualizes diversity from a social, legal, and political perspective.14 For example, while gender equality is generally a global issue, other issues vary by country. In India, the caste system has historically been the focus of diversity efforts, while in the United Kingdom, race, ethnocentrism, and class issues are prevalent. South Africa has historically focused on race but also more broadly on sexual orientation, HIV status, political opinion, and culture.15 It can be overwhelming for organizational leaders to understand the sociopolitical norms in every country their organization operates in and then to master local DEI-related legal statutes. For example, employers must evaluate what employee data is legally permissible to collect; this ruling varies by country.

All these considerations still do not guarantee cross-cultural competence—the knowledge and skills needed to effectively communicate, understand, and interact with people across cultures. Sodexo experienced this challenge when it realized it could not implement certain scorecard metrics that accounted for the ethnic composition of the workforce in France or Germany, because it was illegal to collect this data in those countries.16 Thus, the company had to figure out how to implement the bonus system in a place where it couldn’t use the data the system was based on.

Anand was promoted to global CDO in 2007 and quickly started to understand these intricacies in global DEI strategy. In general, she implemented a rigorous global approach in terms of overall goals and governance and then created flexibility lower down so that programs could be resourced and implemented at the local level in a way that comported with the local needs.

“So we have a global framework around our strategy. And that strategy then gets localized,” she said. “For some, it might be to focus first on people with disabilities, like in Brazil or in France, where they have quotas around people with disabilities. For others, it might be generational considerations, for instance, engaging or retaining youth. In China, for instance, where there’s a lot of mobility in the workforce, that becomes important. Figuring out what those pain points are in different parts of the world is managed locally, but it’s all under a global framework.”

Ultimately, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to a global DEI strategy, and many companies that have made progress in their headquarters region have lost momentum and interest when taking their efforts global. In other situations, employees outside of the organization’s home country will resist DEI efforts that feel generic and indifferent to their local experiences. Amelia Ransom, leader of engagement and diversity at software company Avalara, once shared with me a peanut butter analogy for global DEI strategies. Her analogy has always stuck with me (no pun intended):

You really have to learn what the motivations are in the places where you’re doing business. It doesn’t look the same. Being Black in Brazil is not the same thing as being Black in the Americas, and so we can’t just spread our strategies like peanut butter around the globe. The challenges are different, the structures are different, the expectations and culture are different. So you have to actually be solving for other things. Being a woman is very different in India. The expectations on the family and all look very different from the expectations on a woman in the Americas. . . . But if you can’t center it in the country and not put US expectations on what good looks like . . . You have to have something that suits your organization but also the allowance for regional expectations and regional progress and regional success.”17

Even a seemingly simple task like localizing a workshop on courageous conversations for a multinational company can present cultural minefields that can derail the whole training. In 2021 my consulting organization set out to train people from a US technology customer service organization in ten global locations on how to have courageous conversations about racial discrimination.

In some countries, our work was dismissed as not relevant to their culture (though we know that historically, racism can be found in every region of the world), yet other countries told us our training would be impossible to implement because of cultural norms.18 In some places, it was socially unacceptable to be confrontational, even in the face of discriminatory treatment. My team ended up having to work directly with representatives from each country to make sure the training content would land well in each location while fighting to maintain the core messages of the training so that all employees in the division would be on the same page about company expectations to speak up against discriminatory behavior.

Sodexo dealt with a common localization challenge: DEI was being stereotyped as an American issue. Some country-level CEOs derided the diversity initiative as unnecessary because, they said, “We don’t have those kinds of problems here.”19 As a result, Anand and her team decided to implement a country-by-country strategy that focused on getting buy-in from country-level CEOs and their executive teams, building the business case for each country and training.

For example, the US compliance training was adapted to what the company called Spirit of Inclusion, a more global version that trained executives to identify two important dimensions of diversity in their country and how those were connected to their abilities to drive business in the future.20 This is a strong example of how a global approach to something like DEI training must be altered for local relevance to be successful.

Another global DEI challenge Sodexo faced was uneven progress. Efforts were taking off at faster paces in some places while making no headway in other places, despite similar resources. In Europe, women resisted training on gender equality in 2007, until the company facilitated a discussion about gender that included both men and women.21 At the same time, in India, grassroots gender-equality initiatives such as women’s networking groups, a task force to tackle women’s issues in the workplace, and development of male “diversity champions” were all well received and successful straightaway. One unique challenge in India, however, was that the Sodexo North American mentoring program could not be replicated, because the Indian personnel considered it socially unacceptable for the woman to reach out directly to a male mentor for support. The program had to shift its structure so that the mentor had more responsibility for the mentoring relationship. In China, the experience for women’s gender initiatives was predicated on leadership commitment and partnering with external organizations to develop cross-industry women’s networking events.22

This tailoring of approaches to fit the local norms isn’t easy, of course, but it’s necessary. And to prevent the loss of momentum, seeing and recognizing where there is progress is a key element of every company’s DEI journey. Sodexo’s slow but steady improvements demonstrate the importance of acknowledging progress. In the company’s 2010 diversity and inclusion report, Anand wrote: “Our number one priority globally is to ensure representation of women at all levels of the organization, particularly at the most senior levels. Currently, 20 percent of Sodexo’s senior leaders are women and we have an ambition to increase this to 25 percent by 2015. It is an ambitious target, but we know that it can be done because we have clear processes in place to help us to accomplish it.”23

Indeed, the company exceeded its goal of having women make up at least 25 percent of its top two hundred leadership positions globally by 2015. The proportion was actually 31 percent.24 By 2020, Sodexo had reached gender-balanced teams at most levels of the organization, including 60 percent of the board, 30 percent of the executive committee, 40 percent of all senior executives, 44 percent of managers, and 55 percent of the total workforce.

But the company is not done. Sodexo is racing toward a global goal of having women represent at least 40 percent of its leadership by 2025 and 100 percent of employees working in entities with gender-balanced management teams.25 Sodexo’s global journey toward gender equality has demonstrated the importance of setting DEI goals, having the appropriate tracking metrics, integrating systems of accountability, and having the patience to see the fruits of the collective labor. Sustainable DEI change does not happen overnight even for the most advanced companies on the journey.

Seeing Clients Take Notice and Influence Grow

When clients started to notice Sodexo’s commitment to DEI, the organization was able to catapult its efforts by partnering with clients to have an impact on the organization’s broader sphere of influence beyond its own walls. For example, in 2006 Sodexo and National Basketball Association Hall of Famer Earvin “Magic” Johnson founded SodexoMagic, a community advocacy group with the following mission: “We serve to uplift communities, to advocate equity, to ensure inclusion, to be a force for change. We sustain and empower communities everywhere through healthy food and exceptional services. We stand with our employees and partners to ensure quality-of-life services that safeguard wellness for all communities to create a just and more equitable future for all people.”26

The organization has been successful combating food insecurity in communities and helping to provide clean and safe learning environments with a highly diverse group of more than sixty-five hundred employees serving consumers at more than seventeen hundred sites in the corporate arena, health care, universities, K–12 schools, and aviation.27, 28 SodexoMagic is a key example of an organization that uses its sphere of influence to have an impact on the world of DEI beyond its employee workforce while adhering to its core mission and values. It’s not about being everything to everyone or mimicking what other organizations have done. It’s about being connected to how your core business can create positive impact in the world around you.

“If it’s a health-care organization,” Anand said, “it’s about addressing health-care disparities. If it’s an education organization, it’s about student achievement. If it’s B2B, it’s about your client base. If it’s B2C, it’s about the customer base. Whatever it is, it really has to be core to what the organization is about. I think that helps to expedite moving further along the continuum, going from compliance to getting buy-in and breaking down resistance. The key is embedding DEI within the business and really getting the value from it holistically.”

Sodexo has continued to use its internal lessons learned about DEI to partner with others to increase the external impact of the work. The company realized the value in sharing its work with the broader business community by externally sharing its case studies. In 2014 Sodexo launched an internal study of the correlation between gender-balanced management and performance. This effort became known as the Gender Balance Study, a multiyear, longitudinal analysis of gender parity at all levels of leadership globally at Sodexo, with the goal of expanding research on the business case for women in leadership more generally.29

As the company has matured in its DEI perspective and under the leadership of Anand, it has become a thought leader on a wide array of DEI topics. For example, in 2019 alone Sodexo USA conducted research and published three white papers on varied topics:

- “Why ‘LGBTQ-Welcoming’ Will Soon Be a Hallmark of the Most Successful Senior Living Communities: A Primer for Operators, Marketers & Leadership”30

- “Addressing Culture and Origins across the Globe: Lessons from Australia, Brazil, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States”31

- “Healthcare Administrators: The 2043 Business Imperative—Advocating for Hispanic Leadership in Healthcare and Cultural Competence”32

In addition, Sodexo offers menu guidelines to help mangers be more culturally aware when celebrating global cultures through food choices.33

Still, Resistance

You might think that Sodexo has it all figured out and is cruising on its necessary journey, virtually frictionless. While the company is a model, there’s still resistance. “I’ve worked at Sodexo for eighteen years,” Anand said. “And for eighteen years, there’s always been resistance in different forms. It doesn’t go away.”

Change management scholars will tell you that resistance is an organic part of any major organizational change.34 Resistance to DEI initiatives can be even more complex than resistance to other change management initiatives because of the implicit and explicit social pressures of the cultural climate. In my experience with executives, though, I encourage them to approach DEI strategy with the same rigor and candor that they bring to other business imperatives, because many leaders are still afraid to speak up. A 2020 study by the Society for Human Resource Management found that 32 percent of HR professionals, those who are supposed to be the most well versed on issues of DEI, did not feel safe voicing their opinions about racial injustice in the workplace.35 This lack of comfort with being honest about DEI manifests itself in leaders all signing off on a new, shiny DEI strategy with no understanding of how they are expected to commit to it and no real intention to support it beyond the head nod to HR. You have to meet the leaders where they are.

“The initial resistance was really about meeting people where they were and using individual strategies to bring them along,” Anand said of her two-decade effort at Sodexo. “For some, it was about getting them to mentor individuals who were different from them so that they could then learn from the experiences of the person they were mentoring. For others, it was exposing them to a learning opportunity within the organization. For others, it was engagement in the community and being able to see what those communities go through. In other instances, it was having White males carrying the messages for me. There were a bunch of different strategies in terms of breaking down the resistance.”

Behind it all, of course, was the data and the business case, and those help. But Anand believes that they only get you so far. One of the most dynamic and powerful ways to get resisters on board is to expose them to the opportunity to walk in someone else’s shoes, as Anand explained:

Eventually, people have to feel it in the heart and the gut, to really change their hearts and minds. So it was exposing them to this sort of variety of experiences. For example, we had fishbowl activities with the African American Leadership Forum, where we had the executive sit on the outside of the African American ERG circle and listen while [Black employees] shared stories about their experiences. Then we had the executive [on the outside] speak to their own privilege and how they were going to be committed to DEI. It was a lot of listening to stories and putting other people’s experiences through either structured activities, mentoring, or informal engagements.

In addition to seeing the data through the business case of showing how it’s benefiting the business and benefiting our clients, it was those kinds of things that helped leaders move beyond resistance.

The Journey Continues

It has been more than twenty years since Sodexo faced the shattering class action lawsuit about racial discrimination. The company’s DEI journey started as a compliance exercise with a brand-new CDO. Since then, Sodexo has earned numerous DEI awards, most notably being honored by DiversityInc for thirteen consecutive years since 2008, and in 2021 was named second of the top fifty companies in DiversityInc’s Hall of Fame.36

When asked to reflect on the journey of Sodexo over the past twenty years and how she knew her work made an impact, Anand shared three areas of impact she is most proud of: metrics, culture, and the sustainability of Sodexo’s DEI program:

We struggled to get senior leaders that were people of color, and women in operational profit and loss roles. So just looking at the numbers of senior executives in those roles [who] are women and people of color today gives me a huge sense of accomplishment. When a person says to me, “Look, I had all these choices as a female engineer, but I came here because of the culture, and because of your commitment to diversity . . .” I mean, in 2002, I never thought that I would go beyond that level. But today, I’m a global executive, thanks to the culture [of Sodexo]. I knew that we had an impact when we saw [that] engagement scores of our people of color and African Americans in particular had gone up incredibly high. They had a sense of belonging to the organization. That was a sense of accomplishment. And I think that fact—that when I was not in the room, and there were other people who were advocating for DEI—I knew I had an impact.

Anand cautions leaders that the journey is not over for Sodexo and that organizations must continue to be diligent in their efforts, even once they have reached this level of success: “Although organizations can go from class action lawsuits to best in class, without intentionality and focus, it is easy to slide back. Addressing DEI is continual and relentless.”37

Although Anand has retired as CDO of Sodexo, she still shares her lessons learned with leaders all over the world. When I asked her what a workplace utopia looks like to her, she preached vigilance:

DEI is an iterative process; it’s always evolving. The external landscape is always changing. Utopia looks like an organization not taking their foot off the pedal, constantly addressing it, not slipping back or getting complacent. We must be prepared to constantly be addressing issues and not sit back on our laurels. For example, when the pandemic arrived, a lot of organizations cut back their support for DEI and cut back their head count. And then George Floyd’s murder happened, and all the other events of 2020, and now all of a sudden, companies had to retool again.

But this is life, and it is going to happen. Utopia is to be constantly vigilant and to keep DEI front and center, regardless of what’s happening.