The Metaphor of the House

In order to understand what an option is, let’s relate it to something in the real world. Most are familiar with how real estate works. In real estate there are basically two ways to make money. You can buy the property, live in it, wait a long time, then sell the property, hopefully at a profit. The second way to make money in real estate is to buy the property and rent it out. This brings in an income from the rents regardless of the value of the property. If later you sell the property for a profit then so much the better. But the real income was from the rent, not necessarily from the future appreciation of the property.

The problem with renting the property is that during that time you don’t get to enjoy the use of the property and generally cannot do with it as you please. How could you create an income flow from the property and at the same time maintain all the use, rights, and benefits of the property? There actually is a way.

Let’s assume you buy a house for $120,000. Shortly after purchasing the house, someone comes to you and says that they would like to buy your house, but not now. What they offer is to buy an option on the house from you. Here’s how it would work.

They will give you $10,000 for the right to buy your house anytime within one year for $125,000. Here’s what the contract means. You get $10,000 now. That $10,000 is yours to keep no matter what happens. If the value of the house goes up during the year then the option purchaser has the right, not the obligation, to purchase your house at any time during the year for $125,000.

Let’s say that the value of the house goes to $180,000. Then sometime during the year the option purchaser will force you to sell the house for $125,000. In that event you not only get the $5,000 profit on the sale of the house, but you also get to keep the $10,000 option money that was given to you upfront. Remember you only paid $120,000 for the house. Therefore you made a $15,000 profit on the property.

On the other hand, if the property does not appreciate in value, then at the end of the year, assuming that the value of the house has not changed and is still worth $120,000, the option purchaser would not exercise his right to buy it for $125,000. Therefore you will keep the house, and you get to keep the $10,000 option money. In any event you have made at least $10,000 on the house in a year.

In essence you have rented the house out for the year without the hassles of dealing with tenants, and you got to enjoy the benefits of the house at the same time. Remember though that during the period of the option on the house, you do not have total control of the house. You do not have a right to sell the house during that period. The option owner in essence controls that aspect of your house. The only way that you could sell the house during the period of the option contract would be if you bought the option back from the purchaser. Depending on the value of the house at the time, you may have to pay more or could pay less than the original $10,000 to get out of the contract.

You might say that this is not a bad deal for the property owner. But who in his right mind would buy an option such as this on a piece of property? Let’s look at it from the point of view of the purchaser of the option. We already understand how you will make out from such a deal.

If the purchaser has some kind of information or simply a good hunch and thinks that the value of the house within one year will go to $180,000, then in essence for $10,000 he can control that property during the year. If the house does go to $180,000 he simply exercises his option and buys the house for $125,000 and then immediately resells the house for $180,000. Now he has a nice profit of $45,000 ($180,000– $125,000–$10,000 = $45,000).

Notice that in order for the purchaser of the option to break even on the deal, the value of the house must appreciate at least to $135,000. In other words it has to increase first to the $125,000 purchase price, then another $10,000 to pay for the cost of the option. Remember that you get to keep the $10,000 option money regardless of what happens.

What then is your risk as the option seller? If the property appreciates you have no risk of loss. The only thing that you are giving up is the possibility of making a larger profit than the $15,000 which you will receive if the property appreciates higher than $135,000. No matter how high the value of the property goes, you are limited to a profit of $10,000 on the option plus $5,000 on the appreciated sale of the house. Therefore your risk on the upside is simply a loss of opportunity for more profit. What you are getting then is a bird in the hand. You are making your money upfront on the rental of the house through options rather than tenants. You are giving up the speculation on the future appreciation of the house.

What happens then if the house does not appreciate in value. Assume that the value stays between $120,000 and $125,000. What happens is that the option expires worthless and you get to keep the $10,000, and you can do it again for another $10,000 for the next year if you can find someone to buy the option.

The third possibility is that the value of the house declines. Let’s assume that the value of the house goes down to $110,000. This is where your real risk exists. Obviously the option will not be exercised, and you will get to keep the $10,000. But now if you try to sell another option where the purchaser buys your house for $125,000, you are not going to get as much for the option since the value of the house is $110,000 rather than when the house had a value of $120,000.

In addition at the end of the option contract, if you were to have to sell the house at this time let’s say for personal reasons, then you would take a $10,000 loss on the house. But at least that loss is made up by the option money that you received. Another way of looking at it is that you incur that downside risk any time you buy property. The difference is that you at least have the $10,000 in option money to soften that downside risk. It is $10,000 more than you would have had if you had simply bought the property and held it without selling the option in the hopes that the property would appreciate.

This is all well and good as a metaphor with real estate to help understand how options work. But how on earth do you find people who are willing to buy options on property? In real estate it’s not easy at all. In fact it’s next to impossible. You would have to be sitting on just the right property and have a lot of connections to cut a deal as I have described.

Now let’s turn to stocks. Here it’s not difficult to find buyers who are willing to pay money in order to control your stock for a given period of time. In fact there is an option exchange where options on stocks are bought and sold through brokerages. It’s as easy as selling and buying stock. In fact a market order for an option on the buy or sell side can be executed in a matter of seconds. So you don’t have to go hunting for buyers.

The Call Option

What was described in “The Metaphor of the House” is a call option. A call option gives the buyer the right, not the obligation, to purchase a stock at a specific price within a specific time period.

Here’s how it works. Let’s start with the assumption that you have purchased XYZ stock at $30 per share. You want to sell a one-month option on that stock for $2.00 per share. Assuming that you purchased 1,000 shares of stock then you have invested $30,000 for XYZ stock at $30 per share.

You get a quote on the price of a one-month option at 30 (the price for which the option purchaser has the right to purchase your stock), and you find the 30 option is worth $2.00. Each option contract is for 100 shares of stock. Since you own 1,000 shares you can sell 10 contracts (10 × 100). You tell your broker to sell 10 one-month 30 option contracts at $2.00. So $2,000 (2 × 10 × 100) is now deposited into your account. That $2,000 is yours to keep no matter what happens just like the option money on the real estate.

One month passes by. Remember that the term of the option was one month. At the end of one month assume that the stock price is more than $30 per share. Your stock will be called away from you, meaning that you will have to sell the stock at $30 per share. This is the same price you paid for it. In that event you break even on the stock and make $2,000 for one month on your $30,000 investment.

On the other hand let’s assume that the stock price stays the same. At the end of the month the stock price is $30 per share. In that case your stock will not be called away. You will get to keep your stock and you get to keep the $2,000. Now you can sell options for another month against the stock.

The third possibility is that at the end of the month the stock has declined to $28 per share. Your stock will not be called away and you get to keep the $2,000. You will also be able to sell another 30 option contract against the stock. Albeit you will not get as much money for the 30 option now that the stock is at 28 as you did when the stock was at 30.

The Option Contract

There are several terms that need to be defined before we can continue. They are the option price, the strike price, and expiration.

All options are contracts. There are three components to this contract.

• The agreed-upon price of the option

• The price at which the option may be exercised

• The duration of the option contract and its expiration date

1. All option contracts are for 100 shares of stock. The price of the option is multiplied times 100 per contract. This means that if the price of the option is $2.00 then one contract will cost $200.

2. The price at which the option may be exercised is called the strike price. If you sell an option with a $35 strike price, this means that you have agreed to sell your stock for $35 if it is called away by the purchaser of the option. The process of calling your stock away by the purchaser (requiring you to sell your stock) is known as exercising the option. You will then receive what is known as an assignment. You are assigned the sale of your stock at $35 per share.

In order for this to happen, the stock must be greater than the strike price before the option expires. If the market value of the stock is not greater than the strike price then there would be no reason for the owner of the call option to want the stock at the strike price. If the market value of the stock is below the strike price then the call purchaser could simply go on the open market and buy it for less money.

In actuality you don’t have to do anything. If you are assigned the sale of your stock, then your brokerage will simply sell it on your behalf. You will simply wake up one morning and see that your stock is gone and the money from the sale is in your account. If you did not have the stock in your account then it will still be sold, the proceeds placed in your account, and your account will show that you are short the stock. This means that you must eventually replace the stock you are short.

3. The last component of the contract is the duration of the option contract. This is quoted as a specific day rather than a time frame. Typically the standard monthly contract expires on the third Friday of any given month. (Technically it is the Saturday, but the markets are not open on Saturday.) Therefore a July 35 option on XYZ stock means that the option expires on the third Friday of July with a strike price of $35 per share of XYZ stock. The various strike prices and their expirations are set and fixed by the exchange.

The Covered Call

What we have been describing so far is a covered call. This is the term used when you sell a call option on stock you already own. Therefore you are said to be covered by the stock.

It is possible to sell a call without owning the stock. If you do this you are said to be naked the call. This is probably one of the most dangerous things that you can do. As long as the price of the stock does not go up you are fine. The stock could go to zero and you still get to keep the option money from the sale of the call.

On the other hand if the stock goes up beyond the strike price then your stock will be called away. But you don’t have any stock. Therefore when your stock is sold you will be short the stock and eventually you will be required to purchase the stock on the open market at a probable higher price to replace the stock that you are short. Obviously there is no limit to the loss that can be incurred.

Before you go out and start selling covered calls as a strategy it should be noted that even though if the stock goes up there is no risk of loss, only opportunity, there is risk of substantial loss on the downside. Although you are mitigating that loss with the sale of an option, your real risk for loss is the decline in the value of the stock.

The Put Option

The put option gives the purchaser the right, not the obligation, to force the seller of the option to purchase his stock at a specified price during a specified time period.

What this means is that if you sell one July 30 put option on XYZ stock, any time prior to the third Friday of July you may be required to purchase from the owner of the put option 100 shares of XYZ stock at $30 per share regardless of its market value at the time.

If you purchase a July 30 put option on XYZ stock this gives you the right to force the seller of the put option to purchase your stock at $30 per share regardless of its market value at the time.

Why would you want to buy a put option? Let’s say that you own 100 shares of XYZ stock which you purchased for $32 per share. Earnings on the stock are coming out in less than a month. You are afraid that if the earnings are bad it could devastate your stock. So you buy a put option that expires after the earnings announcement with a strike price of $30. If there are bad earnings and the price of the stock declines to $20 per share, you can force the seller of the put option to purchase your stock at $30 per share. Therefore your loss would only be $2 per share plus the price that you paid for the put option.

No matter how sure you are of your position Murphy is always alive and well. Something can go wrong. And sometimes it can be devastating. You never want to be in a position where if something devastating goes wrong you can lose a good portion of your entire account. Therefore savvy investors will always use some form of a hedge (protection) in order to limit the loss.

Most put options are purchased as hedges or insurance policies against major declines in stock positions. It is also possible to purchase put options as an alternate strategy to shorting stock in the belief that the stock will go down.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Values

The price of a call or put option is determined primarily by the laws of supply and demand. But the law of supply and demand only governs what is known as extrinsic or premium value.

Assume that XYZ stock is selling for $32 per share. A call option with a $30 strike price has a value of $2 intrinsically. What this means is that the owner of the call option can force the seller of the option to sell his stock to him for $30 per share. He can then immediately sell the stock for $32 per share on the open market. Therefore the option has a value of at least $2.00.

This is known as intrinsic value. You can always find what the intrinsic value of a call option is by subtracting the strike price of a call option from the market price if the market price is higher. In the case of a put option, subtract the strike price from the market price if the market price is lower. Ignore the minus sign. An option that has intrinsic value is said to be In the Money. An option that has no intrinsic value is said to be Out of the Money. If the market price of the stock is exactly the same as the strike price it is said to be At the Money.

If an option is selling for more than its intrinsic value then the difference between the intrinsic value and the price of the option is said to be its extrinsic value or premium value.

The price of options which are In the Money will be made up of two parts, intrinsic value and extrinsic value. The price of options which are Out of the Money or At the Money will be made up of only extrinsic value. The price of an option is affected by the price of the underlying stock. Assuming the same amount of time remains until expiration, as the price of the underlying stock goes up or down, the price of the option will also go up or down (although not necessarily at the same one to one ratio).

Let’s assume that XYZ stock is selling for $30 per share. You have purchased a July 35 call option for $1. The next day the stock is selling for $32 per share. Because the stock is closer to the strike price at $32 per share than it was at $30 per share, the value of the call option should also increase. This is because it has a better chance at $32 of being In the Money by expiration than it had when the stock was at $30. How much it will increase is for another discussion. The only thing that is important here is to understand that the $1.00 option that you purchased when the stock was selling for $30 is worth more now that the stock is selling for $32.

Let’s assume now that the stock is selling for $36 per share. The 35 call option now has an intrinsic value of $1.00 per share plus whatever premium it may warrant for the time remaining until expiration. The premium (extrinsic) value is also known as time value because time is what you are really buying when you buy an option.

Opening and Closing Contracts

Whenever you buy or sell an option for the first time you are said to be opening a contract. At any time until expiration you have the right to get out of that contract. This is called closing the contract.

In order to close an option contract you simply create an opposite transaction from what was used to open the contract.

For example: let’s assume that you sold a July 30 call option for $2.00; and $200 was deposited to your account. Time goes by and the price of the stock has not moved. The July 30 call option is now valued at $1.25. It has decreased in value because there is now less time available. At this time you wish to get out or close the contract. Since you sold the option for $2.00 initially, all that you need to do now to close the contract is to buy an option with the same strike price and same expiration for $1.25. It does not have to be from the same person that bought your option. In fact you will never know who that person was.

All July 30 call options are equal and interchangeable. This means that all options of the same type (call or put), the same strike price, and the same expiration date are the same. When you buy back an option that you previously sold or sell an option that you previously bought, then you are closing the contract and have no further obligation. Whether you make money or lose money in the closed transaction is simply a matter of what you paid for the option versus what you sold it for. In the above example you sold the option for $2.00 and bought it back for $1.25. In this case you made $0.75 or $75 profit on one contract.

The pricing of an option is not an arbitrary endeavor. Options can be viewed as the market sentiment on the underlying stock. The more demand there is for an option, be it a put or call, the larger the value of the premium. The largest amount of premium is found with a strike price At the Money. As the strike price goes either further In the Money or Out of the Money the amount of premium on the option is reduced.

Another thing that affects the pricing of an option is how close it is to its expiration date. The premium on an option is reduced exponentially as the expiration date approaches. This makes logical sense. In reality, time is what the option purchaser is buying. This is known as time decay. But time does not decay the premium of an option at a constant rate. The closer an option is to expiration, time decay accelerates at an exponential rate.

Delta

The Greeks are an aid to helping you understand how options are priced. They are Delta, Theta, Gamma, and Vega. These are terms (borrowed from the Greek alphabet) which are used to describe what is happening to the price of an option. For our purposes we are only interested in Delta and Theta. Every brokerage firm’s option software will provide you with these values.

Delta is technically defined as the amount by which an option will increase or decrease in price if the underlying stock moves by $1.00.

But Delta is much more than that. Delta is actually your oddsmaker. If an option is absolutely At the Money it has a 50–50 chance statistically of expiring either In the Money or Out of the Money. Therefore an option whose strike price is At the Money has a Delta of 0.50.

Let’s take a look at how this works. Assume the stock has a price of $100 and its option with a strike price of 100 has a Delta of 0.50. This actually means two things. First if the stock price increases to $101 the premium value of the 100 call option will increase by $0.50 (the percentage amount of the Delta). Of course the price will actually increase by $1.50 because it will now have $1.00 of intrinsic value plus the $0.50 of increase in premium value. If the price of the stock goes to $99 then the call option will lose $0.50 of premium value. The other meaning of a Delta of 0.50 is that there is a 50 percent chance that the 100 strike price option will be At or In the Money at expiration or a 50 percent chance that the 100 option will be Out of the Money at expiration.

For our purposes we are going to be using Delta as the oddsmaker. Other than At the Money which always has a Delta of 0.50, other things can affect the value of Delta. Delta can be affected by volatility.

You can think of volatility as a fear factor. Most investors in the market are mostly long the market, meaning that the purchaser or owner of stock is betting that the stock will go up. As the stock declines in price, fear sets in. The more the stock declines, the more fear there is. This fear is measured as volatility. The higher the volatility, the higher is the price of an option, especially a put option.

Volatility also affects what is known as the expected movement of the stock. This in turn affects the Delta of the option. Remember Delta is the oddsmaker. If the expected move of the stock increases then the odds that it will be In the Money or Out of the Money at expiration is affected.

Theta

Theta is the measure of time decay. It is expressed as either a positive or negative number. For now, pay no attention to the + or – sign. A Theta of +0.45 and a Theta of –0.45 both mean that the option value itself will lose $0.45 per day.

The + or – sign refers to what you personally will gain or lose, not what the option value will gain or lose. Remember that as time passes all options will decay and lose value because of time.

If you are the purchaser of an option then you will have a negative Theta (meaning time decay will go against you). The call option you purchased will lose value as time gets closer to expiration.

If you are the seller of an option then you will have a positive Theta (meaning you will benefit from time decay). The reason a seller benefits from time decay is because the option has already been sold. Therefore it must be bought back at some time or left to expire. Therefore the seller wants the option to be at the lowest price possible when it is bought back or for it to expire worthless.

Theta does not stay constant. It is affected by the passage of time and by volatility. The closer you get to expiration the faster Theta will increase.

Risk Graphs

The purpose of a risk graph is to graphically show you what your risk versus reward is. What it doesn’t do is make a prediction as to where the stock is headed. Furthermore the main part of the risk graph is only valid at expiration.

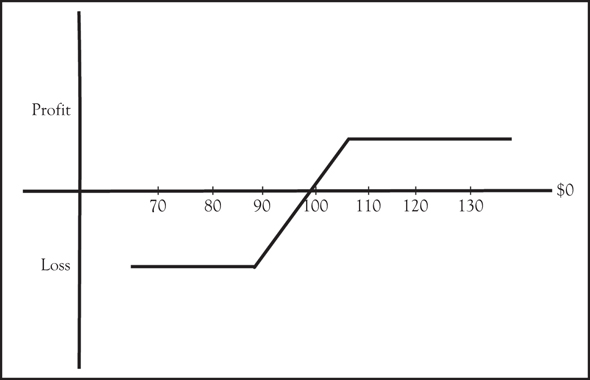

Look at Figure 2.1 This is a risk graph of what is known as a bull spread. The price of the stock is the horizontal line at the bottom, and the profit loss is the vertical line on the left. As the stock is moving to the right, meaning increasing in price, the profit of the position also increases until such time as it reaches its maximum profit potential. At that point no matter how much higher the stock rises the profit is capped.

As the stock is moving to the left, meaning decreasing in price, the loss is also increasing until such time as it reaches its maximum loss. At that point, no matter how much lower the stock declines the loss is capped. You can also tell from this graph what the risk versus the reward is.

Figure 2.2 is a bear spread. As the stock is moving to the left, meaning decreasing in price, the profit of the position also increases until such time as it reaches its maximum profit potential. At that point, no matter how much lower the stock declines the profit is capped.

Figure 2.1 Bull spread

Figure 2.2 Bear spread

As the stock is moving to the right meaning increasing in price the loss of the position is also increasing until such time as it reaches its maximum loss. At that point no matter how much higher the stock goes the loss is capped.

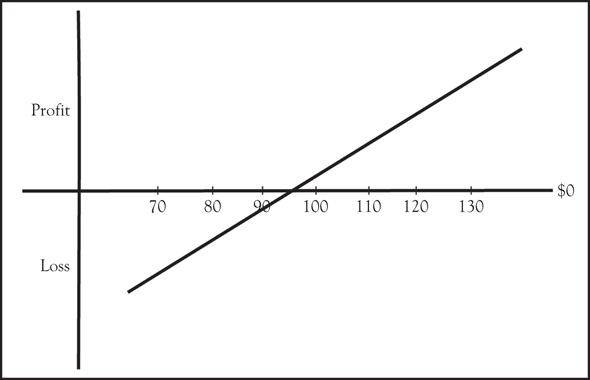

Figure 2.3 is simply a risk graph of a long stock purchase. This means you have simply purchased the stock. As the stock moves to the right and increases in price the profit increases and is never capped. The potential gain is unlimited.

Figure 2.3 Long stock

On the other hand as the stock moves to the left and declines in price the potential loss increases and can be absolute and total.

A risk graph can be created with most brokerage platforms using any combination of options and stock. We will be looking at a risk graph for many of the basic strategies that we cover.