CHAPTER 2

SEEKING VALUE

Blockchain-inspired solutions include three of the five design elements of blockchain: distribution, immutability, and encryption. Organizations are using these solutions to improve record keeping and transparency and to modernize cumbersome or manual processes, including those that cross enterprise boundaries. Through 2023, the majority of solutions inside established organizations and called “blockchain” will be blockchain-inspired and developed for one of these purposes.

Applied in the right context, blockchain-inspired solutions could, for example, improve efficiency; reduce back-office costs; speed up confirmation, settlement, and traceability; and improve data quality and management.1 An example of a high-potential solution that fits these criteria is currently in development at the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) to replace its twenty-five-year-old Clearing House Electronic Subregister System (CHESS), a computer system that records shareholdings, manages share transactions, and facilitates the exchange of title or ownership when people sell financial products for money. Today, CHESS handles as many as two million trades per day.2 The system is a true workhorse, but twenty-five years is a long time in the world of technology. Dan Chesterman, CIO of ASX, explained that he concluded in 2015 that the exchange had reached the natural limit of what it could do to improve CHESS’s capability and efficiency.3

Sticking with the status quo was not an option, given the opportunities and challenges pressing on the ASX. CHESS runs a proprietary messaging protocol, which makes it difficult for the ASX to attract listings from the AsiaPac and the Middle East. The Australian government also opened competition in clearing and settlement of equity trades.4 ASX does not have a credible competitor in Australia, but technological advancement could change that. For those reasons, the organization will need a new system to maintain its status in Australia and be a viable global partner beyond the continent. In 2016, ASX presented its roadmap to replace CHESS with a “distributed ledger technology” (DLT) solution—in other words, CHESS as a permissioned blockchain.5 However, the roadmap also stipulated that ASX will build an ISO20022 messaging option for ecosystem participants that don’t want to use the DLT capability. With this announcement, ASX established itself as one of the first national securities exchanges hoping to use blockchain technology for its mission-critical financial settlement systems.

The ASX and others developing blockchain-inspired solutions see benefit in using this new technology, even without tokens or decentralization as part of the design. Starting with equities, the ASX plans on incorporating other securities asset classes and new products. Eventually, this vision could be a building block in revolutionizing the Australian markets and others. There are risks, however. We clarify those benefits and risks for you in this chapter and give you tools to evaluate the solutions you see in your market.

To be clear, we firmly believe that blockchain-inspired solutions do not deliver on the full promise we see for the real business of blockchain. Still, these solutions are not without value. For the right application in the right context, they could enable improvements in document management, traceability, and fraud prevention and create other efficiencies. Using a taxonomy of blockchain-inspired archetypes, we discuss ways to distinguish the high-benefit solutions from those with low benefit. But before we describe the archetypes, let’s revisit the matter of centralization in blockchain-inspired solutions and how it affects the four business currencies (data, access, contracts, and technology) that form the core of the blockchain-inspired benefit-risk calculation.

BUSINESS CURRENCIES WITH BLOCKCHAIN-INSPIRED SOLUTIONS

To recap, the four business currencies are major sources of value and competitive advantage in digital, not just blockchain, environments. In the simplest interactions, users “pay” for free access to software or a digital solution with the details they reveal about their interests and habits; the digital platforms in turn use this data to attract advertisers, develop new products and features, and increasingly steer customers to take certain actions. The lack of an explicit and multilateral contract between the user and the digital platform provider means there is no limit to how much data the provider can collect or how often it uses the data and in what situations.

All centralized digital platforms exert control over the data that runs through them. This means that blockchain-inspired solutions exert centralized control over data just as digital platform do. Furthermore, because blockchain-inspired solutions are not designed to be decentralized, they instead operate with some level of central coordination and governance of the network. Centralization is achieved by including aspects of database management mechanisms as part of the information architecture; the database mechanisms determine which entity acts as a transaction authenticator and validator and therefore decides what gets written to the ledger. Although, as we explained earlier, a blockchain is not a database and lacks a central authority, blockchain-inspired strategies blur those distinctions. Some would argue that a “centralized blockchain” is a contradiction in terms and that a blockchain that includes a database is not a blockchain at all. Ignoring these semantic arguments, we call these solutions that exploit database technology blockchain-inspired.6

Most important, a centralized solution has a single authority and does not use a decentralized consensus algorithm to validate the identity of participants and authenticate the transactions. Also, a centralized architecture with a single authority creates a single point of failure for the network. Put simply, all the promises you hear about blockchain as more secure and reliable than traditional data architectures are not true if the design is centralized. Security is not the only consideration, either. Without tokenization and decentralized consensus, a blockchain-inspired solution cannot enable participants who do not know each other to exchange value without a third party validating the exchange.

Ownership over a blockchain solution becomes a major issue with solutions under central control. With decentralized blockchains like Bitcoin, there is no owner and access is open to anyone (pseudonymously) who wants to participate and has the infrastructure to do so. Blockchain-inspired solutions, in contrast, usually have one owner or a limited group of owners, and membership is restricted to the parties invited by the owner to participate. For that reason, blockchain-inspired solutions are also referred to as closed, private or permissioned blockchain networks.

These dynamics of technological and business control have a direct impact on the competitive opportunities and threats a given solution can enable. Figure 2-1 reprises figure 1-3, which mapped the degree of digitalization or programmability and the degree of decentralization operating in the business environment. In figure 2-1, blockchain-inspired solutions are represented by the shaded area, with clear boundaries based on the degree of centralized control.

FIGURE 2-1

The blockchain-inspired benefit zone

This figure offers a strategic view of what centralization means for a blockchain. Any given blockchain-inspired solution will capture a smaller band of territory in relation to the degrees of digitalization and decentralization. Some blockchain solutions, such as ASX and its CHESS replacement, provide a highly controlled and centrally operated and governed solution to a market problem. The rationale for this choice is sound. As Chesterman explained during an on-stage conversation at Gartner IT Symposium/Xpo October 2018 in Australia, “We aren’t solving a trust problem. People do inherently trust the ASX to be the source of truth for the data that is in CHESS. We’re solving a data synchronicity problem.”

Other solutions that are similarly led by one company or a small group of companies may aim to exert control over others in the value chain. Eventually some solutions hope to evolve toward decentralized collaboration over time. The distinction can often be seen in how a solution trades in the four business currencies. Let’s examine each currency, with an eye on how it operates in the blockchain-inspired phase of the spectrum.

DATA

Data is an important currency at all stages of the blockchain spectrum, but it is most vulnerable during the blockchain-inspired phase.7 This vulnerability is especially apparent with blockchain-inspired solutions designed to facilitate interorganizational interactions in a value chain. If your organization participates in one of these blockchains, and the governance of that blockchain allows a single actor or subgroup to access or control all the data that flows through it, then you may be exposing your business information without receiving commensurate insight or value in return.

To demonstrate what we mean, we’ll use the example of the blockchain collaboration TradeLens. Launched in August 2018 by shipping giant Maersk and global technology firm IBM, TradeLens is a blockchain-inspired logistics solution designed to streamline information sharing in the supply-chain industry.8 Daniel Wilson, director of business development in Maersk for the TradeLens collaboration, told us that the solution came out of a larger exploration of digital solutions for the logistics industry. “There is a dire need in our industry for digital transformation, such that all participants have reliable and predictable information flows. We saw that a blockchain platform would go at least some way to remedying those pain points.”

For context, more than five thousand container ships sail the earth’s oceans, and some of these vessels carry as many as twenty thousand containers of worldly goods.9 The shipping industry needs air-tight records to manage those volumes, but much of this record keeping is still paper based. If the documentation is incomplete, is written in the wrong language, or is lost, goods can be held up, creating additional costs.

TradeLens aims to digitalize the process by capturing the necessary shipping information on a blockchain-inspired platform that allows the actors involved in a transaction to access the record when they need it. The TradeLens network had over one hundred global logistics sector participants at its August 2018 launch, and by October 2018, the platform had managed 154 million shipping events, with daily volumes reaching 1 million. Maersk reports that the network of onboarded TradeLens participants represent 20 percent of the addressable global shipping market, and promoters highlight the potential of blockchain to cut the time spent on shipment administration by 40 percent.10

The promise is there. Yet the centralized approach gives some industry actors pause. Executives from German transportation company Hapag-Lloyd, for instance, have publicly expressed their resistance to participating on a platform owned and controlled by a competitor. “Technically the solution could be a good platform,” CEO Rolf Habben Jansen said, “but it will require a governance that makes it an industry platform and not just a platform for Maersk and IBM. And this is the weakness we’re currently seeing in many of these initiatives, as each individual project claims to offer an industry platform that they themselves control. This is self-contradictory, without a joint solution, we’re going to waste a lot of money, and that would benefit no one.”11

When we asked Wilson about the issue of governance, he said, “The perspective of many in the industry is that having a platform that facilitates standards for information sharing would be an unalloyed good, but they have concerns about the governance model. And we’ve changed the governance in the last twelve months to reflect that industry feedback. We are listening to the market. We haven’t heard anything negative in a material sense about the technical approach.”

On the technology, Wilson added, “We are working through various forums for the discussion of standards. We are using open-source technology; all the data structures are open. Someone else could take the same technology and build their own platform, but why would they do that? The value is having all the information in one place, having a one-stop shop.”

Meanwhile, a rival shipping industry blockchain-inspired solution has been announced. The Global Shipping Business Network has nine shipping industry signatories, including COSCO and the Shanghai International Port. The network has declared its intent to develop a blockchain solution, though what the solution will look like in practice is not yet clear.12

The data access and commercial concerns expressed by Hapag-Lloyd come up with any solution built with centralized technology governance and central ownership. The concerns are exacerbated for information-intensive solutions. When blockchain-inspired solutions allow a single large company with superior AI analytical capability to view and access the data and influence the flows from every party in the system, the benefits could accrue disproportionately to that actor, with the disparities multiplying over time. The lack of tokens in blockchain-inspired solutions reinforces the centralization of power, since there is no mechanism to allow participants to control their information, provide consent, or trade it as an asset.

Thus, when we say data is a currency, we mean that the form, ownership, and governance structure of blockchain-inspired solutions can give participants more or less control over the data they input. Know what and how you’re “paying” before you sign on to such solutions.

ACCESS

The business that owns a blockchain-inspired solution controls access to a process or a portion of the market. Businesses that want to participate pay for that access explicitly through fees or a subscription, but they also pay implicitly by locking themselves into the solution or exposing their competitive information.

In contrast, the concept of permissioned access doesn’t exist in blockchain-complete solutions. Any participant or node can join a blockchain peer-to-peer network. The blockchain design in fact favors participation because decentralized consensus-based decision making gets stronger and more trustworthy when more nodes are involved. Access and participation define the ethos, grounded in the idea that transparency drives adherence to the rules. The concept is similar to eBay’s early use of member reviews to allow people to call out bidders or sellers who didn’t honor the terms of an auction. Make it open, transparent, and accountable, and everyone will play nice.

The theoretical benefits of open access are clear, but the reality is more complicated. Open access is a challenging concept for many leaders used to seeing boundaries inside and beyond their organization. For them, a blockchain-inspired solution, with its permissioned access, defined interactions, and known actors, is more familiar and comfortable and can be applied today within their organization.

Yet there is risk in these familiar waters. Taken to an extreme, blockchain-inspired solutions trade on scarcity rather than availability. Solution creators make these forms of blockchain useful so that “customers” and “partners” see short-term benefits. But this “value” could be coerced in the right circumstances. For instance, a major customer or channel partner could make participation in its centrally controlled blockchain a condition of ongoing partnership. In these situations, access to the blockchain solution will be synonymous with access to the market. If you refuse, you lose the ability to connect with your end customer.

CONTRACTS

Contracts specify the terms and conditions of doing business. In blockchain, those terms are captured in the technology of the blockchain itself, either as a smart contract—lines of code that capture and execute the business rules and agreements of a blockchain—or in the underlying technology stack.a The rules allow the blockchain to execute transactions without human intervention.

But who defines these rules, and who decides on modifications to them? If one actor defines the rules and owns the blockchain, then there is reason to be wary. In contrast, if decisions are community based and the smart contracts and their maintenance are transparent, they could serve as equalizing forces that keep the rules and their consequences visible. You therefore need to understand the source of the smart contracts, who is in charge of the maintenance of the related code, and who bears the liability in the event of an error. Smart contracts and the rules they execute should never be regarded as a technical issue. It’s a business issue, as control of the contract gives control over the value produced and exchanged by the blockchain.

TECHNOLOGY

There’s a battle under way in the technology sector to define the dominant systems used to build blockchain solutions. The stakes are as high as those of the past, the combatants both familiar (IBM, Oracle, Intel, SAP, Microsoft, Samsung SDS, etc.) and new (Ethereum, R3, Quorum, NEO, Digital Asset, Fisco, and over a hundred other potential platforms). The familiar competitors stake their authority on worn positions: trusted source versus open source, stability versus flexibility, and so on. Vendors are going hard after enterprise blockchain budgets. Some have designed specific solutions to common industry issues. Others claim that they can build anything.

Many of the solutions that are already live are transitional; their primary purpose has been to fulfill an immediate need or opportunity. They should be viewed as learning platforms, not as long-term solutions, since blockchain technology is continuously evolving and maturing. The ongoing maturation of blockchain technology is important, particularly with blockchain-inspired solutions, since solutions built with centralized governance cannot be easily (if at all) decentralized later. The technology designed for a centralized architecture cannot be used for decentralization, and vendors have no incentive to enable it, especially if the blockchain uses their system and technology stack. Open solutions built from the outset to handle some degree of decentralization will allow you to upgrade faster and evolve in that direction over time.

BLOCKCHAIN-INSPIRED ARCHETYPES

The four business currencies offer a lens for evaluating the hundreds of blockchain-inspired solutions in development right now. How does a solution handle data? Who gets access? Who defines the contracts? Who develops the technology? Answers to these questions clarify the balance of benefits and risks in blockchain solutions on offer from trading partners or vendors. Having these answers could also help you decide in advance what qualities you want in the solutions you build or buy.

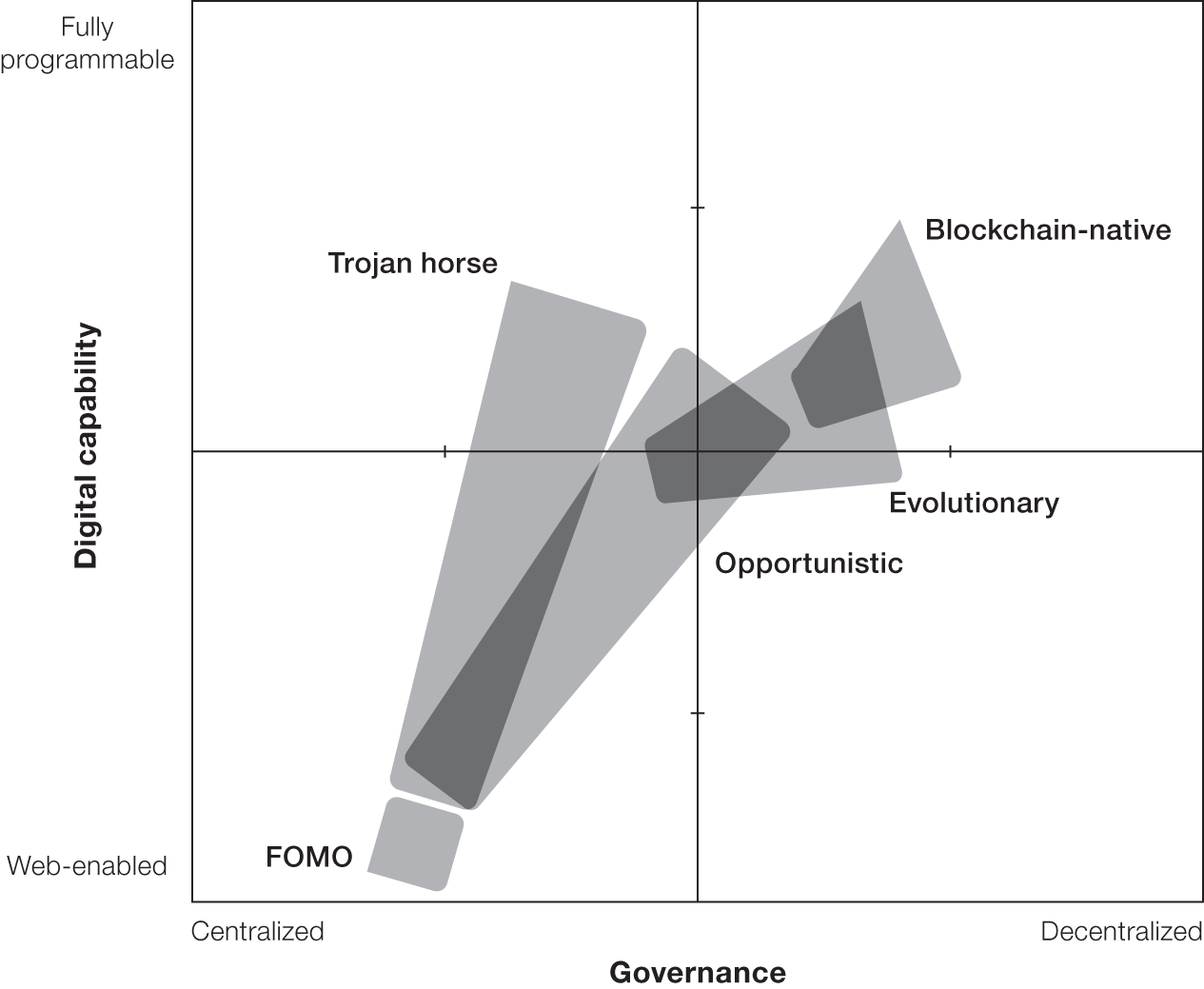

You’ll be asking these questions often, given the explosion in blockchain activity we see in the market. The hundreds of blockchain-inspired proofs of concept, pilots, and implementations under way vary in how they deal with the four currencies. In light of those differences, we have identified five blockchain-inspired archetypes (figure 2-2). Some of them keep open the possibility of evolving to a decentralized, tokenized model over time; they can migrate from blockchain-inspired to blockchain-complete if design principles permit. Other archetypes reinforce centralized operational approaches that are incompatible with blockchain-complete solutions. You incur risk in adopting any new technology, but you will benefit from taking a first step. To help you decide how, we present a closer view of the five archetypes.

FIGURE 2-2

The blockchain-inspired archetypes

FEAR OF MISSING OUT (FOMO) SOLUTIONS

In a recent conversation Christophe had with leaders of an auto insurance company seeking to develop a blockchain solution for automotive claims handling, we asked a question common to these kinds of client interactions: Why blockchain? The leaders wanted to capture and store information about the driver, the vehicle, and the context of an accident, believing this data could streamline accident investigations through a more transparent process. Yet none of what they described requires blockchain. In fact, blockchain in this closed, centralized context could be more expensive, complex, and higher-risk than alternatives built with standard database and messaging technology. Christophe told the leaders what he thought, but they shrugged and said their senior leadership had told them to find a way to use the technology. The company’s desire to use blockchain is less a reflection of the technology’s relevance to the problem than it is a reflection of pressure on organizations to keep up with digital trends.

We regularly hear from organizations developing blockchain tests or pilots to address an in-house problem that could be solved better, faster, and more cheaply with an established approach. For some leaders, the hype around blockchain creates tunnel vision that makes them unable to consider alternatives. Other leaders know that they should compare different options but see no value in doing so; their boss, under the influence of blockchain FOMO, has said go blockchain or go home. As the CIO of a regional financial services firm told David at Gartner’s Middle East Symposium in 2018, “You don’t understand; my CEO told me to do blockchain.”

FOMO-driven blockchain projects are unlikely to save costs or create value. They are not pointless, however. Exploring an advanced digital solution like blockchain could send a message to the market that your organization is innovative and on top of current trends. That message can cause prospective customers to give you a second look. It can also force competitors to invest time and resources for similar FOMO reasons.

Yet leaders need to be wary of developing a false sense of security about their knowledge of blockchain and carefully control the money they spend on these kinds of solutions. If a project fails to produce value, some leaders will believe they tried blockchain and failed, when they simply had the wrong use case. Too many FOMO blockchains damage the credibility of blockchain in the business. In addition, when businesses insist on preemptively implementing blockchain solutions in the enterprise, these solutions often burden the existing systems and processes and create additional costs that bring no increase in efficiency.

TROJAN HORSE SOLUTIONS

For this archetype, one powerful actor or a small group of actors develops a blockchain-inspired solution and invites—or sometimes requires—the ecosystem participants to use it. These solutions are by definition blockchain-inspired because they have a single owner or a small collective of owners who are known to each other. Though some providers with centralized solutions will use words such as decentralization and consensus (a feature of decentralized systems), the archetype’s central ownership strongly indicates that the system design is centralized as well.

We’ve dubbed these solutions Trojan horses because they look attractive from the outside. They have a respected brand behind them, they enjoy seemingly strong technological foundations, and they address known, expensive, and wide-reaching problems in an industry. Yet the price of admission is potential exposure of proprietary data and process and commercial activity without equal access to the same. Viewed through the lens of the business currencies, Trojan horse solutions require the participants to relinquish some control over their data and contracting terms in exchange for access to markets and technology.

Walmart’s food-tracking blockchain appears to fall into this category.13 This solution was developed to track the produce supply chain. Walmart was reportedly motivated by the desire to prevent foodborne illness and reduce the costs of produce contamination. In the non-blockchain environment, it can take weeks or longer to pinpoint the exact farm or processing plant responsible for a contamination, and dozens of people can fall ill in that time. Such an outbreak occurred in the United States in late November 2018 involving romaine lettuce, which disappeared from store shelves for more than a month after the incident.14 These events waste uncontaminated produce and damage brand reputation. Complete, accessible records will allow stores like Walmart to more quickly pinpoint the origins of a contamination and stop it at its source.15

Undeniably, the industry needs better ways to stop food contamination. Yet once supply chain partners input their data to a centralized system, those companies risk getting locked in to sharing their data with that system but without due compensation for that information.

The potential long game for Trojan horse blockchain-inspired solutions follows the path of market disintermediation—a path cut by powerful channel partners since the beginning of the industrial age. At first, these dominant firms encourage trade partners to participate by offering a solution to an existing problem and access to a desired end customer. But once in the system, the participants are locked in—the platform owner can refuse to do business with them unless they stay or accept new terms and conditions.16 Over time, these Trojan horses can analyze the platform data and shift sourcing to the lowest-cost or lowest-leverage actors in the network. They can also gradually pressure producers to increase quality, reorient production, and lower costs so the platform owner can attract more customers, which encourages still greater polarization of volume. Customers benefit at first in the form of greater convenience, improved products, and lower costs. Eventually, however, the consolidation of power in the market decreases competition, which risks making the supply less reliable, less diverse, less influenced by customer choice, and more expensive. Put directly, Trojan Horse solutions drive deeper centralization.

OPPORTUNISTIC SOLUTIONS

The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) is the post-trade clearing and settlement intermediary for the US financial system. Like the ASX in Australia, the DTCC manages post-trade processes and serves as a single source of record for trading activity in the US market. In 2006, the DTCC built a mainframe solution called Trade Information Warehouse (TIW). As Robert Palatnick, managing director and chief technology architect for the DTCC, described it, the mainframe was supposed to be “the central golden record of credit default swaps.”17

“There were a lot of manual and paper-based processes which the mainframe addressed when the solution was launched in 2006,” Palatnick said. “But since the financial crisis, a number of exchanges have been created and the volume of over-the-counter trades is down. With the mainframe due for an upgrade and the size of the market decreasing, we found the cost to be too high. So we came together with technology providers, experts, and our clients, and decided TIW represented a good opportunity to do something significant and impactful with blockchain.” The company is currently working to design its TIW using distributed ledger technology and cloud-based solutions. When we spoke with Palatnick, the TIW was in structured testing with fifteen participating banks, and managed roughly $10 trillion in outstanding positions.

Like the CHESS replacement in Australia’s stock exchange, TIW falls into the category of opportunistic blockchain-inspired solutions. These solutions address known problems or opportunities, and the initiating company has qualified the risks of using untested technology, the costs associated with blockchain as compared with other technological options, and the benefits that are likely to accrue. The solution is blockchain inspired, but there is no pathway to increased decentralization (nor would a central authority like the DTCC want it).

Opportunistic blockchain-inspired efforts offer value through improved record keeping or process-level efficiencies. The Australian stock exchange also saw the potential to derive additional value from market expansion to customers outside its main geographic area.

Organizations also gain useful experience with opportunistic blockchain-inspired solutions. These efforts lend credibility to the technology and to the implementing team and give everyone experience with some of the cultural and technical challenges of distributed data sharing.

For the former CIO of a Middle Eastern bank who went live with a blockchain payments initiative in early 2017, the benefits of opportunistic blockchain-inspired solutions were worth the effort. The solution was designed to connect a defined group of high-volume customers operating in different countries to execute cross-border payments without the intermediary SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication). The system was taken offline after six months, however. According to the CIO, there was “a lack of ROI.” Talks with a large overseas partner that planned to use the system collapsed, and without those volumes, the system was not worth the costs.

Still, the CIO spoke positively of the experience. He said his bank gained confidence in blockchain as reliable for that specific use case, and his technology team learned how to build and operate a blockchain system. “We got good experience of how it all worked, we spent [very little], we discovered that working in even the smallest of consortia was painful, and our tech exit strategy maintained the client experience.” He added, “It was good PR for the bank!”18

Put again in the perspective of the currencies, opportunistic blockchain-inspired solutions present some loss of control over data and contracts. But as the bank CIO acknowledged, the solutions do offer some payoff in market access and technology experience.

EVOLUTIONARY SOLUTIONS

The technological immaturity of blockchain today makes complete solutions difficult to implement in an environment with mission-critical systems. Nevertheless, some organizations are exploring blockchain-inspired solutions that they intend to evolve toward blockchain-complete as the technology matures. To maintain the possibility of a future transition, owners must, from the outset, make architectural and operational decisions that enable decentralization and tokenization, even if those elements are not used in the initial deployment.

Sweden’s effort to build a blockchain real estate registry offers a useful example of a solution with evolutionary potential. In much of the developed world, private citizens hold a majority of their wealth in their homes, which people may use as collateral to secure low-interest loans. Despite the economic relevance of property as an asset, buying and selling real estate is an onerous, technical process that is limited in form. Owners, buyers, and real estate agents trade copious documentation at the point of sale, sharing the paperwork with mortgage companies, banks, and legal entities involved in verifying ownership and reviewing contracts and financial arrangements. Each actor may receive, fill out, or review the documentation digitally, but the number of process steps and the volume of people who touch each transaction can stretch the process by weeks or months and introduce error, more so when paper is involved. Additional delays follow after “closing” once the paperwork goes to the government registry office, where it can languish for weeks before officials record the sale and issue a formal title. Those time lags can be costly, limiting opportunities in the real estate market, creating numerous parallel and inconsistent systems, and allowing fraudulent owners to apply for loans or make business deals on properties they don’t own.

Sweden’s Lantmäteriet, the government mapping and land registry office responsible for regulating real estate, is testing a blockchain solution to clean up the process and potentially save $106 million annually. It formed a partnership with SBAB Bank; Landshypotek Bank; Telia Company, a telecommunications firm; Kairos Future, a management consultancy; and ChromaWay, a blockchain technology vendor. As Lantmäteriet Chief Innovation Officer Mats Snäll stressed, “The goal is to develop a blockchain ledger on which real estate transactions will run, with nodes eventually distributed and ideally decentralized across organizations in the ecosystem.”19 The Lantmäteriet blockchain network could eventually include mortgage lenders, real estate brokers, law firms, real estate agents, property developers, and private buyers and sellers. The aim is to enable a more efficient and transparent record than exists with today’s public register of real property.

The first transaction took place in the network in June 2018. In its nascent, “inspired,” form, the system operates as a closed or permissioned network running on a limited number of nodes. Each party to the property exchange uses a separate interface to access the network, and the system uses a combination of technologies, including a centrally-managed database instead of a ledger. No digital tokens are included within the initial design. A smart contract validates the process, but the contract is currently not self-executing: it merely validates that an exchange happened; it doesn’t execute the exchange.

The Swedish Lantmäteriet must resolve several issues before it can reach scale. Some matters are administrative (e.g., Swedish law requires ink signatures on real estate transactions while European Union law allows for e-signatures), and some are operational (the various participants in real estate transactions have different business cases for participation, not all of which are aligned). The blockchain solution might also surface cultural problems. For example, customers may need time before they accept a decentralized, digitalized process for exchanging their primary source of wealth. Financial questions, such as who pays for the solution and who benefits from it, must also be addressed. Finally, the Lantmäteriet must consider the regulatory governance of multiparty networks. What’s more, a group of banks and real estate companies are developing a competing online web portal system that could divide the market or become a better short-term solution. These challenges notwithstanding, promoters of the blockchain land registry assert that the solution could evolve into a network that connects all the actors in an ecosystem in a “permissionless” way. The business currencies in such a solution would trade at a low to moderate risk level for participants.

BLOCKCHAIN-NATIVE SOLUTIONS

The fifth and final blockchain-inspired archetype are the solutions “born on the blockchain.” Developed by startups or greenfield innovation efforts, these solutions create a new market or a disruptive approach to an existing business model using blockchain as a foundational element. Some solutions in the native archetype are still blockchain-inspired due to the immaturity of the core elements of decentralization and tokenization, but their development separate from existing enterprise environments will allow them to evolve toward blockchain-complete solutions over time.

One sector with significant blockchain-native activity is higher education. Woolf University, for example, is a native blockchain entity that hopes to become the first blockchain-powered educational institution. Founded by a group of academics from Oxford and Cambridge, it aspires to be a nonprofit “borderless, digital education society,” a decentralized Airbnb for degree courses. Woolf University connects professors with students via secure contracts and captures a record of the learning exchange so that the student can get credit and the professor can get paid. The WOOLF is the native token used in the smart contracts, but instructors can choose to be paid in WOOLF or in their country’s fiat currency. Woolf University will seek EU accreditation and anticipates a global platform launch in 2019.

Native blockchain-inspired solutions will insert new business models or approaches into legacy industries. Untested technology will be the major currency risk. These solutions will appeal to participants who want to control their own data and experiment with decentralization.

BLOCKCHAIN-INSPIRED SOLUTIONS ON THE PATH TO DECENTRALIZATION

The five archetypes of blockchain-inspired deployments clearly illustrate the wide world of exploration in blockchain. The designs and business motives underlying each archetype dictate both the costs of participation and what you get from it. Solutions based on FOMO can offer some opportunities to learn but rarely advance an organization’s digital capabilities or degree of decentralization. A Trojan horse carries its participants steeply north on the grid in figure 2-2, enabling stronger digital capabilities but within a centralized model. Opportunistic solutions carry implementing organizations in a northeasterly direction, but hit a hard limit because of their lack of decentralization. Evolutionary and blockchain-native solutions have the greatest potential to prepare organizations for decentralization and future blockchain-complete deployment.

The majority of businesses that derive measurable value with limited risk will do so with an opportunistic, evolutionary, or blockchain-native archetype. Trojan horse blockchains will gain market attention and possible traction, but are unlikely to bring long-term value to anyone but the platform owner. If time and market pressure were to change Trojan horses’ ownership structures, then these prototypes could evolve toward an evolutionary model.

YOUR REAL BUSINESS LENS

WHAT DID YOU LEARN?

Blockchain-inspired solutions will dominate the market until around 2023. These solutions take advantage of three of the five key blockchain design elements and usually address known challenges involving intra- or interenterprise data sharing and workflows. Well-designed solutions will bring benefits, but you need to weigh the risks and costs involved. Because blockchain-inspired solutions lack decentralization as a design element, participants who do not know each other cannot trade or exchange value without a third party validating the exchange. Instead, these solutions usually have one owner or a limited group of owners, and membership is restricted. In this context, the business currencies of data, access, contracts, and technology could be controlled by a single actor or subgroup, depending on the design and purpose of the solution. The five blockchain archetypes reflect varying degrees of centralization: FOMO-based solutions (most in-house projects), Trojan horses (e.g., Walmart), opportunistic solutions (e.g., ASX), evolutionary efforts (e.g., Sweden’s Lantmäteriet), and blockchain-native solutions (e.g., Woolf University).

Organizations cannot use blockchain-inspired solutions to create or exchange new forms of value, as new digital native forms of value require tokens operating in a decentralized environment. Thus, the blockchain-inspired phase of the spectrum is not an end game but rather a way station en route to the blockchain-complete phase.

WHAT SHOULD YOU DO ABOUT IT?

As a leader, you will want to review and benchmark your blockchain development against the four business currencies of data, access, contracts, and technology to understand the mid- to long-term value propositions and risks. Ask the following questions with your executive team: How will your organization pursue blockchain initiatives? What archetypes best fit with your strategy? How will you manage your business currencies? If you’re already involved in blockchain pilots, proofs of concept, or full implementations, are the solutions inspired? If they are, where does the network data reside? Who has access to it? And who writes the contracts?

WHAT’S NEXT?

Organizations pursue blockchain initiatives for internal use and through partnerships and consortia efforts in a specific market, geographic location, or value chain. Indeed, consortia have been the driving force behind much blockchain activity. Consortia also present a significant challenge for organizations, despite the potential benefit of sharing risk with like-minded partners. You should remain wary of ceding control to a powerful central power or to competitors. To consort or not to consort? That is the question we address in the next chapter.