CHAPTER 5

Stewardship and Craftsmanship

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

—Buckminster Fuller

American architect, systems theorist, inventor, and futurist

It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.

—Attributed to Dr. W. Edwards Deming

America’s eminent scholar, on the methods for management of quality

The assignment of a returning heroic chief executive—master of two worlds—is knitting together the spiritual world with the world of common day. That means creating synthesis among a business system’s attributes such as people (their capacity to think critically and creatively), the quality of operational processes (their capability and capacity), resource management (its efficiency and effectiveness), customer satisfaction (being their obvious choice supplier), profitability, sustainability of business practices, social responsibility, environmental consciousness, and brand identity, to name but a few. In other words, making trade-off decisions rather than favoring features of one world to the exclusion of any of the other.

Note that trade-off decisions that disrespect humanity, society, and the environment are bound to create friction and conflict on some level and at some point in time—most likely when the system is already experiencing unusual levels of stress.

Making trade-offs requires discernment, which relies on insight and understanding of the business system’s purpose and its capability and capacity to become its target audience’s obvious choice supplier. For example, during an economic downturn, one could decide to reduce the labor force, defer system maintenance, and halt research and development activities to reduce cost, thus maintaining or even boosting short-term profitability. Alternatively, one could decide to compensate for a drop in the labor force’s time spent on routine work flow by catching up on back maintenance, initiating new product development, and conducting employee training. The difference between these two decisions becomes particularly evident in a business system’s readiness when economic conditions improve again.

Another difference between these two decisions is evident in the decision-making process—using quantitative or qualitative arguments. Quantitative arguments are firmly rooted in dominant thought patterns of the world of common day—the level of thinking that brought us to where we are today. Decisions are then rationalized with easy to corroborate performance ratios that rely on setting arbitrary numerical goals, in what is known as Management by Objectives (see the sixth business gremlin, everything is created twice).

Qualitative arguments, on the other hand, are based on theory, principles, values, opinions, personal experience, gut feeling, intuition, instinct, or mojo. The following quote, often attributed to Albert Einstein, is rather apropos: “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.”

I believe that intuition and instinct are closely related to the spiritual world in the sense that they contain wisdom, an unwavering knowing, which does not involve reason or any cognitive process. And their benchmark for success is one’s experience of inner peace. Now, be honest with yourself; how many times have you rejected your intuition or instinct and come to regret it? What I am advocating here is that a master of two worlds uses both quantitative and qualitative arguments as demanded by current conditions and unfolding new and unforeseen events. Practical wisdom, remember?

BRIDGING THE DIVIDE BETWEEN NEEDS AND WANTS

Every sales course advises its students to engage a prospective client at the point where his or her mind is at that time. Prospective clients should not be expected to do any mental gymnastics—such as performing a mind shift—so they can catch up with the seller’s level of thinking. For this reason, I observe a divide between the nature of education, management advice, and leadership coaching that executives say they “want” and what they actually “need.” Professor Philip Kotler1 defined a human need as a state of felt deprivation in a person, and a want as a culturally defined product or service that will satisfy that need.

We know what executives’ wants are from market research in the form of studies, questionnaires, and reports—such as the one conducted by IBM on dealing with complexity—and focus groups. Typically, wants are technological tools—electronic devices and software applications—or a leadership and management methodology. What is missing from most of those research efforts is addressing any specific executive needs that those wants are supposed to fulfill. Then, what is an executive decision maker’s need when confronted with a stubborn systemic problem? What are the critical success factors and prerequisites that make a solution—a want—into an authentic solution? How can anyone identify a want when the need is still unknown?

As discussed in Chapter 1, business problems become personal problems for the chief executive. Consequently, executive decision makers’ needs are for stewardship and craftsmanship, a topic discussed briefly in Chapter 4 under the heading “Light Side of the Force of Life.”

In order for a CEO to practice stewardship and craftsmanship, the leader will need to develop a keen appreciation for the flow of energy and information between a business system’s key component parts, which is ultimately responsible for its behavior, performance, and outcome. This flow of energy and information is what I call business mechanics. Once decision makers develop this value consciousness for business mechanics, they are less likely to harm or undermine good business mechanics with their decisions. What I mean to say is that many solutions could satisfy a decision maker by blunting specific symptoms, but only a few will enhance a system’s business mechanics as well—to realign the system’s capability and capacity with the purpose for which the system was created.

Consequently, executives’ needs for solving stubborn systemic problems is the moral will (stewardship) to practice business mechanics correctly, and the moral skill (craftsmanship) to explore which practices make for good business mechanics.

The notion about what is right—what makes for good business mechanics—is similar if not equal to what Robert M. Pirsig describes as quality, in his epic book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values. According to Pirsig, “Quality is the continuing stimulus which our environment puts upon us to create the world in which we live.”

This is no definition of quality because, as Pirsig explains, “to take that which has caused us to create the world, and include it within the world we have created, is clearly impossible. That is why quality cannot be defined. If we do define it, we are defining something less than quality itself.”

Pirsig continues with an explanation for why he believes that what is right for one should not necessarily be right for all. “In a sense . . . it’s the student’s choice of quality that defines him. People differ about Quality, not because Quality is different, but because people are different in terms of experience. . . . [I]f two people had identical a priori analogues they would see Quality identically every time.”

Needless to say, not every decision maker has the same interpretation of what is right because not everyone has the same experiences.

Rather than applying prescribed solutions, or wants, without any serious investigation of their appropriateness given the current state of the business and its desired state, learning the principles of business mechanics is what bridges the divide between needs and wants. In the words of Benjamin Franklin, “Being ignorant is not so much a shame, as being unwilling to learn.” 2

STEWARDSHIP

Stewardship is an appointed position of authority that is bestowed upon the person who accepts responsibility for the management of assets that are given in his or her trust by its beneficiary. Stewardship is also a discipline regarding the responsible planning and management of resources. Stewardship—the moral will to do what is right—relies on a theory or system of moral principles and values to assess whether a course of action is good or bad. A steward is held accountable for the soundness of their discernment in their decision-making processes.

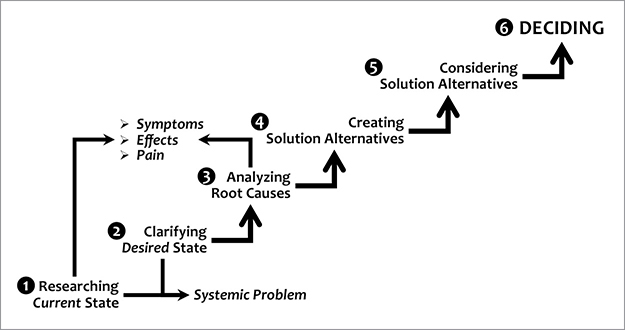

Figure 5.1: Sound Decision-Making Process

Decision makers are held accountable for their decisions, which they can only justify successfully when they have done their homework—when they can explain convincingly how they arrived at their decision.

We obtain a better understanding of the meaning of the verb to decide by considering its Latin origin, decaedere, which means “to cut off” (derived from de [off] and caedere [to cut]). What is cut off are alternative options or courses of action. In other words, it means coming to a resolution or choice in the mind as a result of discernment, consideration, or settling an argument. Reaching a successful decision takes many steps (see Figure 5.1).

The role of a chief executive is that of a steward who is responsible for the sustainable development of a business system’s capability and capacity in order to realize the system’s intended purpose for which that system was specifically created. CEOs are thus expected to leave the company in better shape—which includes more than simply its financial health—for their successor than when it was handed over to them by their predecessor.

The immediate monetary beneficiaries of a business system are the owners or shareholders, who share in the profits when the company does well but lose, to a maximum of their invested amount, when the company does poorly. Hence, the naming of their investment as risk capital. Ultimately, the potential reward should be commensurate with the potential risk, which is an integral part of an investment decision.

Shareholders are part of an extended group called stakeholders, which is any individual or group of people who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives. In addition to shareholders, this group includes indirect beneficiaries, or people whose livelihoods and well-being are tied to that of the business system, such as employees, vendors, buyers, users, professional service providers, the community in which it operates, local government, and trade associations.

Stakeholders and enterprises are bound to each other by contractual relationships. Each party gives up something in return for something else, which makes it a two-way street. Of course, the numerous stakeholders in an enterprise have various self-interests that may not always be properly aligned with each other. In fact, they may be conflicting. Solving such conflicts is the exclusive domain of the system’s steward, which demands of him or her the moral will to do what is right and thus to avoid and resolve friction and conflict, making sure that a chosen solution does not provide seeds for future conflict.

Moral Compass

We already established that a steward knows a solution is “right” when she or he experiences peace of mind. Will, as in moral will to do what is right, refers to a steward’s intention—informed by the voice of the id—to value humanity more than shareholders’ desire for money. This matters because by eliminating humanity—the spiritual world or the path of the heart—from the equation, decision makers can defer the defense of their decisions to cold-hearted mathematical calculations.

The certainty that universally verifiable mathematics provides is intended to unburden a decision maker’s conscience, which is often expressed to stakeholders in the all too familiar advice: “Don’t take this personally, this is business.” This line of reasoning wants us to believe that emotion should be separated from business (that is, when it suits a decision maker). After all, employees are expected to be fully engaged and motivated, and to have heart for the business. Yet such emotional investment is personal.

However, morality is not a luxury (the affordability of which is debatable); it is critical to the successful resolution of any conflict, large or small, in private, public, and among nations. As Einstein said, “Not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted.” A lack of moral fiber, demonstrated by either an individual or a corporation, influences public opinion and thereby people’s behavior toward the culprit. Don’t underestimate the influence of globalization and social media on your reputation.

Although the consequences of such a change in behavior, as measured in monetary terms, is unknown and unknowable, successful stewards must nevertheless take these into account during their decision-making processes. After all, employees who trust that management will do the right thing and will fight for the success of their employer instead of “looking out for number one,” which is the main reason the war for talent exists.

To paraphrase Colonel John R. Boyd: tools and technology do not increase bottom-line results; employees do when they use their minds.3 Employees have finely attuned antennae for picking up cause-and-effect relationships between their experience of friction and conflict and executive decisions. They use their own moral compass to discern what is right and wrong, and they will act accordingly. In addition, they are willing to do the near impossible to make a wrong decision work, up to a certain point and for a limited amount of time only. So, don’t tick them off unnecessarily—that is, without a defensible reason.

CRAFTSMANSHIP

Trying to determine the essential attributes of craftsmanship is, perhaps, an attempt at defining what may prove to be indefinable. Craftsmanship is not the only indefinable concept in the English language. This is how Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart described, rather than defined, hard-core pornography in his opinion in the 1964 case Jacobellis v. Ohio: “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description, and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.”

While we all recognize craftsmanship—the moral skill to identify the right thing to do—and while we can describe what it looks like and how it makes us feel, we cannot formulate a conclusive definition of those succinct qualities that turn performing a trade or profession into craftsmanship. Craftsmen possess an inner knowing about what constitutes doing something the right way. They do not question whether they should be doing it any other way. Moreover, cutting corners goes against their natural disposition; it violates their integrity and thereby the id of who they are. Because there is pride and honor in their work, you cannot even force them to do what is wrong—it is just not done, period.

In developing my own craftsmanship in root-cause analyses and change leadership, I learned to identify the complex interdependent relationships among the major tangible and intangible aspects of a business system, and how to make them visible with simple and easy-to-comprehend models as you see throughout this book. Note that the relationships between separate individual parts are what turn individual value links into a value chain. Therefore, a value chain is only as strong as the weakest relationship—interface—between two value links.

Communication

Responsibility for the successful maintenance of these relationships is often incorrectly ascribed to the discipline of communications—an academic discipline that deals with processes of human communication. This silo of specialized knowledge is just a channel or medium for passing messages between a sender and a receiver—it is the faucet, not the water. Its main concern is to accurately convey the sender’s intent and to avoid or reduce noise from garbling the content.

However, relationships (connections) that tie separate value links (nodes) into a value chain (network) are shared boundaries across which information is exchanged. These shared boundaries are commonly known as interfaces. Although proper communication processes may improve clarity of transmissions, the essence of an exchange of information is in its content, which demands familiarity with the principles of business mechanics.

Unfortunately, few silo managers possess that kind of knowledge. In fact, interfaces have become a no-man’s-land between two or more links of the value chain for which very few leaders feel any sense of responsibility. Why? Because we have committed ourselves to the process of managing the actions of individual links of the value chain rather than their interactions. As a result, issues that remain unattended are falling in the cracks between two silos of specialized knowledge. These issues make themselves known enterprise-wide in the form of acute or latent problems, and they will persist, recur, or become acute until they are addressed with an authentic solution.

In a worst-case scenario, latent problems can become acute, and acute problems can grow in severity, or even reach a fatal date—urgency—after which their detrimental power skyrockets or can no longer be corrected and causes a business to implode. This was discussed in Chapter 1, under the subheading “Measuring a Problem.” By now you should understand why alleged performance improvement measures such as benchmarking, accountability, and cultivating “A” players/teams are ineffective; no individual value link can outperform the capability and capacity of the value chain as a whole.

Establishing and maintaining properly working interfaces within a complex network of business processes requires a give-and-take decision-making process that is cognizant of what needs to be done three to five steps into the future and across multiple value links, which is a key characteristic of craftsmanship. Imagine the feeling of extreme frustration when finding oneself in pursuit of an intended outcome (effect) that requires a specific course of action (cause) that is no longer available because of a past decision by you or your executive? This is the message made visible with a decision tree.

Pursuing the creation and implementation of prescribed generic deliverables and milestones as a precondition for changing a specific system’s behavior and performance are doomed to fail because no two business systems are identical in their level of complexity and their reaction to unfolding events. However, once you understand business mechanics, you don’t need to memorize tricks, procedures, or best practices because you are capable of figuring out what the system requires here and now by yourself.

Knowing Why

Performing one’s trade or profession the right way does not imply a faithful reliance on following a strict protocol that prescribes when, where, and how specific tasks must be performed and which tools should be used. Craftsmanship is about knowing the goal of a methodology, what it aims to accomplish, why something is done, when, how it works, where to apply what practice, and by whom. The why is informed by circumstances, such as the task at hand, the materials or substrate with which to work, critical success factors that determine the success of the end result that a principal intends to achieve, and prerequisites that determine the success of the production and delivery process, including cultural, environmental, social, and ethical aspects.

Typically, artisans require fewer specialized tools because they know how to perform a greater variety of tasks with the same tool. Just visit Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, where modern-day craftsmen are still making exquisite colonial furniture with period hand tools—no computer-controlled routers or laser-guided power tools in sight. They are testimony to the fact that craft is in the man (or in the woman), not the tool. Craftsmanship is, first and foremost, a way of thinking with some tools attached. And, executives who invest more in tools and technology than in craftsmanship are themselves the cause of complexity, which they decry as the source of their bewilderment.

In Understanding Variation: The Key to Managing Chaos, Donald J. Wheeler discusses the uses and limitations of tools:

While it is easy to focus on the tools, and while it is easy to teach the tools, the tools are secondary to the way of thinking. Learn the tools and you have nothing. You will not know what to do. You will not know how to use the tools effectively. Learn and practice the way of thinking that undergirds the tools and you will begin an unending journey of continual improvement. Without major capital expenditures you will discover how to increase both quality and productivity, and thereby improve your competitive position.4

Craftsmanship in business is an individual executive’s unique ability to translate performance theories (relationships between cause and effect) into their intended physical results (relationships between means and ends). The success of such translations depends on understanding the principles that govern business mechanics and the possession of sufficient insight to predict the outcome of one’s actions—tools are just a means to an end, not an end in their own right. Success depends on the design of the business’s facility, organizational climate, and corporate culture, which are unique executive responsibilities.

Quality

In other words, craftsmanship is an individual’s expression of quality. Therefore, craftsmanship is expressed differently by different individuals, because each has different experiences with properties that constitute quality for them.

Quality is the path one chooses to walk through life, and the experience of peace of mind is its sign of success; that is how you know you are on the right track. Pirsig says about peace of mind: “That which produces it is good work and that which destroys it is bad work.”

Therefore, executive decision makers must possess the ability to see what looks good and an ability to understand the underlying methods to arrive at that good, which is not a one-size-fits-all criterion. Expecting that good will naturally follow when applying the underlying methods is an illusion. Pirsig writes, “The way to see what looks good and understand the reasons it looks good, and to be at one with this goodness as the work proceeds, is to cultivate an inner quietness, a peace of mind so that goodness can shine through.”

This goodness occurs when subject and object become one and their activities effortless. Athletes describe this experience of concentration on the present moment as “being in the zone.” In classical music, it’s the difference between playing all the notes flawlessly while showing great technical command of one’s instrument, and pouring one’s heart and soul into interpreting the spirit of a musical composition with great sensitivity to emotional feelings of oneself and others.5 Craftsmanship is not exhibited in what one thinks but in how one thinks. It’s not about what one is expected to perceive as reality but in how one perceives reality for oneself. Although knowledge can be transferred to another person, it cannot be understood for that person.

Therefore, rote learning is no substitute for gaining understanding, insights, and wisdom. Obtaining a keen insight into the complex relationships between means and ends and cause and effect is like doing push-ups; no one can do them for you. No one can make you do them; you must want to do them yourself. Yes, it will be hard, but once you gain that insight, you open a door to a whole new world of possibilities and opportunities that are yours for the taking. You will have, what German psychologist and linguist Karl Bühler called, an “aha-erlebnis”—or what we call an “aha moment”—named appropriately after the word that is commonly uttered when new insight is gained. There is a clear difference between knowing and understanding!

PAINTING THE BIGGER-PICTURE PERSPECTIVE

Whenever you paint a bigger-picture perspective of the challenge before you, you are going to discover what the right thing to do is. Because you have discovered what is right and can articulate why it is right, doing what is right becomes easier too.

Process mapping is a wonderful method for painting bigger-picture perspectives. All you need to do is identify where the process you want to map begins and ends as well as what actors are involved (people, departments, processes, functions, computer applications, interfaces) and then take inventory of their behavior—the actual activities and tasks they perform. You will discover an unexpectedly large number of interactions between actors, with frequent interdependencies on each other for the successful completion of the tasks they were designed to perform.

Process maps demonstrate that a business system is a network of nodes and connections. They show how the success of one department is dependent on that of many others, even if they are not performed within the same building, city, state, or country, thus breaking down the walls between departments and responsible managers. I like to say that the benefit of having these maps is you can hang them above your desk because they will start conversations. After all, these maps make it possible to trace the consequences of a decision, omission, mistake, or change in specific daily activities of one department on that of one or more other departments. This explains why it is not uncommon for their effects to be experienced enterprise-wide, which is another way of saying that they are inherent to the system’s design, organization or structure, implementation or operation, maintenance, and management. Process maps demonstrate why solving systemic problems demands executive sponsorship for change.

A process map’s level of accuracy can range from a detail-oriented flow of data, information, documents, or objects to an aggregated rendition thereof. And I can report from personal experience that making processes visible creates common ground among all participants, even when relationships between two or more of them are polarized. When everyone identifies their own specific contribution within a mapped process, in relationship to that of anyone else, they realize they are all in the same boat. Everyone takes pride in their own work, knowing all too well that no one knows more about what goes on inside the mapped process than the ones who are actually doing all the work. From there on out, finding the root cause(s) and creating an authentic solution becomes a team effort.

Scale Preferences

General George S. Patton Jr. discussed the issue of perspective in relationship to the required scale of maps:

Whereas most commanders demanded the most detailed, largest-scale maps they could obtain, Patton declared his “opinion that, in the High Command, small-scale maps [which show a larger territory with fewer details] are best because from that level one has to decide on general policies and determine the places, usually road centers or river lines, the capture of which will hurt the enemy most.”6

Big-picture perspectives challenge actors to break out of the comfort zone of their own world, within their specific area of expertise, within one of the nine links of the value chain. They need to let go of a high level of detailed, analytic knowledge, and embrace more general and synthetic knowledge instead.

In his televised interview with Bill Moyers on the topic of The Power of Myth,7 Joseph Campbell referred to Colin Turnbull’s experience when visiting with Mbuti Pygmies, a nomadic tribe of hunters and gatherers living in the dense jungle of Zaire.8 One day, Turnbull brought a Pygmy, who had never been out of the jungle, onto a mountaintop. The man was utterly terrified by the panoramic view of the plains below, stretching as far as the eye could see. Because the animals grazing on the plains in the distance looked so small, he believed that they were ants just across the way from where he stood. Having lived his life among the trees, he had no practice in judging perspective and distance. He literally could not see the forest for the trees. Overwhelmed by this new and unexpected experience, he rushed back to the familiarity of the forest, which was a landscape without horizon.

This shows that one cannot understand the mechanics of a business system as an integrated whole from the perspective of one of its component parts. Moreover, many people feel insecure when confronted with a different perspective on the reality of their daily routine. A common knee-jerk reaction to the experience of uncertainty is to strive for certainty, which—by means of micromanagement—tends to make processes more rigid and resistant to change. Because the world around us changes, we are changing right along with it.

Therefore, the antidote to uncertainty is adaptation to change. Reliant on practical wisdom, executive decision makers will know the right course of action, and they are thus motivated to provide their wholehearted executive sponsorship for change. And they are committed to follow through until completion.

The High Price of Gold Plating

Understanding a business system starts with the acquisition of fundamental knowledge about what a business system is. Unfortunately, the way we are educated about business is through in-depth analyses of the nine separate links that constitute the value chain. Each link is then broken up even further into narrowly defined silos of specialized knowledge. Motivated by personal performance goals and annual performance evaluations, managers within each silo develop their own doctrines and assumptions regarding the (financial) contributions of their individual silo to a business system. Moreover, numerical performance goals that encourage operational efficiency are still perceived as successful, even if they reduce effectiveness and cause difficulties for other departments further down the end-to-end process.

As Deming pointed out, when you take apart a motorcar into its component parts, you no longer have a motorcar; you have a collection of parts. Then, when you reassemble the motorcar using only the top components that the motor vehicle industry worldwide has to offer, there is neither a guarantee that all those superior parts will actually fit together properly, nor any assurance that this motorcar will actually deliver a superior performance.

Strict compartmentalization of a business system, in addition to a management approach that sets arbitrary financial or numerical goals for every silo manager with line-item responsibility, causes everyone to dance to the beat of their own drummer. Each department develops the latest and greatest in their field of expertise and promotes the implementation thereof—including its requisite tools—within the business system. They will even compete with other departments for additional budget to realize their ideas for their silo only.

For the purpose of calling attention to this unfortunate phenomenon, Colonel John R. Boyd coined the derogatory expression “gold plating,” remember, an urgent reminder that rethinking the allocation of limited funds—resource management—is way overdue.

Undermining Operational Effectiveness

Boyd worked on the development of fighter aircraft that had the intended purpose of gaining and maintaining air superiority.

The negative effect of gold plating is an increase in aircraft complexity, a higher all-up weight and larger size, which increases the drag ratio, wing loading, and visibility from the ground and in the air while reducing her maneuverability. This is then compensated with an even bigger engine that burns more fuel, requiring larger fuel capacity—which increases her weight even more. Because the aircraft is now bigger and heavier, she develops more drag, has a higher wing-load, is more visible, and is less maneuverable. This calls for even more state-of-the-art solutions such as stealth technology, that . . . I trust you understand where this rant is going.

Not only are gold-plated aircraft more expensive to buy—they are also exponentially more expensive to operate and maintain. After all, maintenance of a gold-plated aircraft’s additional specialized systems, functions, and components requires more time and increased crew training. In addition, expensive specialized replacement parts need to be kept in stock.

Consequently, to offset these cost increases, aircraft designers now develop a multipurpose aircraft, thus tapping into budgets of several service branches of the armed forces. The suggestion is for the Air Force, the Navy, and the Marine Corps to share the same airframe, albeit with some adaptations to satisfy each of their specific needs.

Because these gold-plated multipurpose aircraft require a longer turnaround time, their readiness for action is less than that of a single-purpose aircraft. Readiness is even further reduced by the smaller number of aircraft that each service branch can afford to acquire and operate.

In conclusion, aircraft designed as a compromise between the specific needs of two or more service branches—each tasked with distinctly different defense functions—results inevitably in suboptimization—an aircraft that is a jack-of-all-trades, master of none. Moreover, it is rather ironic to read about low tech, or even antiquated, technologies defeating high-tech developments. The all-too-common practice of gold plating defeats the specific purpose of a technologically advanced aircraft.

Likewise, gold plating individual processes, departments, computer platforms, silos of specialized knowledge, or value links has an equally negative effect on business system performance. The actual benefits of adding glamorous tools and advanced technology hardly ever outweigh the drawbacks of subsequent increases in system complexity and decreases in operational effectiveness at becoming the target audience’s obvious choice supplier. Therefore, such change initiatives should not even make it to an executive’s short list of investment proposals. Sound stewardship should act as a safeguard against this unfortunately common trend or best practice.

Creating a Common Point of Departure

That said, in order to design, build, develop, or change a business system—which includes solving systemic problems caused by complexity and events—every participant with deep domain expertise should start from the same departure point.

Although doctrines and assumptions regarding different areas of expertise are necessary, no doctrine or assumption should be allowed to dominate the conversation. Having one doctrine rule what is right risks creating false impressions that anything else must be wrong.

Executives often say conflicting ideas are wrong because they never heard them before. Therefore, decision makers must be encouraged to study, contemplate, and question unfamiliar doctrines and assumptions when they are advanced by people within various areas of expertise. After all, looking at the same challenge through the lens of different doctrines only increases one’s understanding of it—aha-erlebnis—which in turn increases the chance of developing better hypotheses and theories that result in the creation of previously unknown and unexpected solutions.

When Boyd started the development of a new jet engine for the future McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle fighter aircraft, he found himself surrounded by engineers who covered a wide range of disciplines and specializations. Needless to say, every one of them understood a jet engine from a different point of view. Therefore, Boyd feared, because they already had an engine, that each engineer would just focus on identifying deficiencies one by one among those parts within their area of expertise and then come up with suggestions for improvement. Yet no individual part has an independent effect on the engine’s performance. In other words, no single part can cause the engine to outperform its current capability and capacity. Consequently, performance improvement of a part—including elimination of deficiencies—should only be conducted if and when it improves performance of the system as a whole simultaneously.

Moreover, eliminating unwanted characteristics does not imply the system is now everything you would want it to be. Therefore, instead of directing attention to characteristics that are not wanted, attention should be focused on properties that are wanted. Boyd wanted those engineers to identify properties and characteristics they would want right now, not at some future date, if they could create whatever they would want to create. After all, if they cannot envision that here and now, then how could they be expected to revolutionize the jet engine in the real world where conditions constrain their abilities.

To prevent any doctrine or assumption from restricting anyone’s vision for the new engine’s ultimate design possibilities and performance capabilities, Boyd created a common point of departure by describing a jet engine as follows: “Cold air goes in the front door; hot air comes out the back door; it goes faster, and we call that thrust.” He wanted every functional expert to measure the validity of their contribution to the new jet engine against this common departure point—major premise—as opposed to trying to justify any gold plating exercises against the doctrine of their own area of expertise. As a result, they developed an engine that exceeded everyone’s expectations.

Similarly, for us to create universal understanding of the mechanics of a business system, we should define a common point of departure for all leadership positions and all areas of specialized knowledge within the nine functions of the value chain.

The reason why this is necessary becomes painfully apparent when business leaders are asked to describe what a business system is or to draw an image of what it does. Their replies range from making money to organizational charts, process maps, logos, products, and buildings. There is no consensus. Contrast this with mentioning the Statue of Liberty, the Golden Gate Bridge, or the Eiffel Tower, when instantaneously an image pops up in your mind, an image that is the same for everyone, even if you never saw any of them in real life.

With everyone judging the opinions of others—and validating their own opinions against fundamentals of areas of expertise with which they are, or are believed to be, familiar—everyone is right and wrong at the same time. Without a common point of departure, discerning which ideas, concepts, challenges, and solutions are in the best interest of the system as an integrated whole is confusing at best and catastrophic at worst.

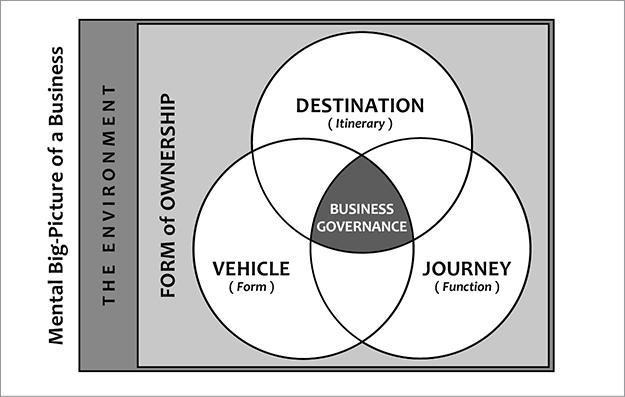

For us to understand and communicate the fundamental principles of a business system—the business mechanics that are responsible for its behavior and performance—I designed a mental big-picture perspective, displayed in Figure 5.2, as my preferred common point of departure.

Figure 5.2: The Business Mechanics Model

In order to provide all participants with a common point of departure, the author created this business mechanics model—a mental big-picture perspective of a business as a singular, unique, integrated, and open system.

Every journey that is undertaken with an intended destination in mind requires a vehicle that is appropriate for that particular journey to that particular destination. Because the individual parts of this trinity (journey–destination–vehicle) are interdependent of each other in complex ways, changing the destination requires the journey to be adjusted or changed as well. And a decision to pursue a different destination causes inevitable changes to the journey. When the journey is changed, the vehicle must be adjusted or changed accordingly because form follows function. Then, when the vehicle changes, or is proven to lack the necessary capacity and capability to continue the journey toward its destination, either the journey or the destination needs to be adapted. Shaping and adjusting of business mechanics is the unique function of business governance.

Journey

Typically, when we talk about business, we refer to commerce, doing business, or the exchange of products or services for money (income generation)—in other words, every form of interaction with members of one’s intended target audience. The journey describes how the vehicle—see below—participates in and establishes its presence in the market, both physically and emotionally. These activities become tangible and visible in marketing and branding expressions, customer service, and other forms of social engagements, including sponsorship agreements, philanthropy, and demonstrations of corporate responsibility and environmental consciousness. The journey is, so to speak, the counterbalance to the supply side of the value chain.

Earlier I used the expression “forms follows function.” So, if the journey is the function of a business, then the vehicle is its form.

Vehicle

Every business is a manmade system, which means it is an integrated whole that consists of two or more parts—it cannot be divided into independent parts. Furthermore, the essential properties that define such a system are properties of the whole, which none of its parts possess individually. In other words, a system is not the sum of its parts; rather, it is the product of their interactions. Therefore, when a system is taken apart—analyzed—it loses its essential properties and, so do its parts.

Parts that belong to a system share the following characteristics:

1. Each individual part has the ability to affect the behavior of the system as a whole.

2. The effect an individual part can have on the system depends ultimately on the behavior of at least one other part; all parts are interconnected—no part is isolated.

3. Each part can be taken to form a subset or sub-system. Yet, just like individual parts, no subset has an independent effect on the system as a whole.

Characteristic of such a manmade system is its purpose-built nature—it is, so to speak, a vehicle for the pursuit of a well-defined destination, following a deliberate or strategic itinerary that describes the journey ahead. Without the vehicle there can be no journey. Hence, one can tell the function of such a vehicle simply by observing its form and behavior—form follows function. Who would mistake an iconic yellow school bus for a dump truck or a taxi?

Whenever a business system—the vehicle—is said to have a purpose of its own, it’s raison d’être, the system functions as an organism as opposed to a mechanism. So, what is the principal purpose of any organism? Survival. And it is necessary for the organism to develop its capability and capacity to adjust and adapt itself in order to survive the uncertainty and disruptive effect of new and unforeseen circumstances.

Now, what about the purpose of the parts of an organismic system, its organs? They don’t have any. Instead, they have a function that supports the purpose of the organism of which they are an integral part. Notice the language of business becoming biological. The chief executive of a firm, or the senior manager, is generally referred to as the head. And the firm or company is now called a corporation, which is a reference to the Latin word corpus, or “body.”

Unfortunately, not everyone has adopted an organismic perspective on business systems. Too many current decision makers are still stuck in an outdated mechanistic perspective, which suggests that the purpose of a business is not inherent to the manmade system itself; a business system has no purpose of its own, and therefore, neither do its parts. When the Chicago school of economics Professor Milton Friedman expressed his opinion that the only legitimate business of business is business, he clearly demonstrated a mechanistic perspective on business.

Following this line of thinking, as a machine or a tool, the business is just an instrument of its owners, and its only function is to maximize the monetary value it generates for those owners or shareholders. Executives—agents acting on behalf of the machine’s owners or its shareholders—are said to have a fiduciary responsibility. Being a fiduciary means being bound both legally and ethically to act in the shareholders’ best interests. But, what about executives’ fiduciary responsibility for the interests and well-being of employees, buyers/users, the community, and the environment? Which theory justifies degrading the interests of buyers/users—the source of the money shareholders desire—to one of lesser importance?

The unrelenting pursuit of operational efficiency may suggest that the vehicle is perceived as one big cost center that is standing in the way of growing net profits. Do people believe that the way to maximize shareholder value is to minimize cost? In other words, do they believe that profits become infinite when cost is reduced to zero?

It should be evident that executive decision-making processes differ significantly with the decision maker’s perspective on business as a system, and so does the outcome or effect of those decision-making processes. These differences can be explained to a decision maker but they cannot be understood for him or her. Understanding takes a willingness to learn, unlearn, and relearn—to search for the underlying principles that explain why business results, outcomes, or effects are as they are.

Destination

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines destination as “a place to which one is journeying or to which something is sent,” but also as “the purpose for which something is predetermined or destined.” These descriptions seem to align best with an organismic perspective on a business system, indicating that the reason for its creation and its continued existence is inherent in its purpose and its realization of that purpose.

The purpose of a vehicle refers to more than its anticipated outcome; it refers implicitly to the process by which that anticipated outcome is pursued and achieved most successfully. It raises questions regarding a decision maker’s vision, values, ethics, beliefs, interests, personal background, previous experiences, and cultural traditions, as well as the system’s status quo and the current geopolitical and socioeconomic situation in which it operates. Many businesses share the same purpose, for example, building family homes. Yet individual builders can distinguish themselves through their process or philosophy of building, such as tract or cookie-cutter houses, custom-built, certified net-zero or passive house, green building, fast system-built, or 3D printed. These distinctions form the basis of a competitive advantage, thus appealing to different market segments. And, in order to maintain one’s competitive advantage, a business system needs to develop its capability and capacity continually in order to survive and to remain relevant to its intended target audience.

Decision makers with a mechanistic perspective on a business system think of themselves as the owners and shareholders. They make decisions based on what is best for them, what serves their own purpose for owning or investing in that business. Why, then, would they bother spending time and money on developing the system’s capability and capacity, or pursue continual process improvement? If all you care about is growing the business—increasing the business’s size and bottom-line results—then buying other businesses is often regarded as more efficient than developing your own existing business.

When development is regarded as an unnecessary expense, as opposed to a money-making proposition, and the business system is perceived as a machine, the modus operandi becomes “don’t fix it if it ain’t broke, and replace it if it can’t be fixed.” If executives perceive the business system just as tool, then any tool should do as long as it gets the job done, right? Then why do they expect employees to be engaged and to show passion, commitment, and loyalty? Employees rightfully ask themselves, “What’s in it for me?” (other than a pay check).

A mechanistic view dehumanizes the workforce, which causes many contemporary enterprise-wide problems, such as employee disengagement and rapid turnover—both of which increase costs. Beware of the fact that employed people are human beings with purposes of their own. Also, outside groups protest the way organizations infringe on their purposes in life. So, if you don’t like the effect of your decisions, the unintended consequences, then stop its cause!

Business Governance

Because a CEO possesses ultimate authority to make changes to the trinity of destination, journey, and vehicle, she or he is in effect the business system’s governor.9 Hence, business governance is the function that is ultimately responsible for the success and failure of the business system as an integrated whole.

Alas, business governance seems to occur only by happenstance. Instead, everyone focuses on their favored kind of leadership developed for different business models and under different conditions, such as international, global, strategic, agile, moral, change, charismatic, innovative, command and control, laissez-faire, pace setter, situational, transformational, and servant leadership, among others.

These different leadership approaches prescribe specific interpersonal behaviors, actions, and areas of focus, including the selection of which tools to use for different purposes, all in the name of guiding employees in the successful fulfillment of their daily activities. These are poor substitutes for proper business governance, which involves the design, organization or structure, implementation or operation, maintenance, and management of a business system. It is imperative that leaders know the why behind their decisions and actions. Also, it makes accountability a lot easier.

We must recognize the limitations of leadership as another silo of specialized knowledge. After all, different styles of leadership are no more capable of changing the character and nature of a business system than one’s driving style is capable of changing the engine, drive train, and suspension-steering configuration of a motorcar.

The behavior and performance of a business system will only change in relation to the changes of its business governance: how it is designed, organized or structured, implemented or operated, maintained, and managed. It is rather unfortunate that thought leaders as well as the curricula of institutions for higher learning seem to elevate leadership studies over management studies.10

After all, leadership principles are not a more advanced form of, let alone a replacement for, management principles. Leadership does not solve any of its practitioners’ resistance to providing executive sponsorship for change, because it does not provide a solution to executives’ bewilderment when faced with system complexity and the disruptive effects of new and unforeseen events on its tightly coupled processes. That’s why I wrote The Root Cause!

A business system cannot perform in any other way than how it was given the capability and capacity to behave. This proves that the purpose of leadership is different from that of business governance, and it is therefore no substitute for business governance—because no CEO can lead a business system without understanding its governance principles. We’ll explore this further in Chapter 9, which is exclusively devoted to business governance, and Chapter 10, which discusses the role of the chief executive and the symbiotic relationship between business governance and leadership.

Form of Ownership

The character and nature of business governance is influenced by the business system’s ownership structure—whether it is privately held, family owned, employee owned, or publicly traded. In addition, a business system can be funded by outside groups such as angel investors, venture capitalists, strategic capital investors, or institutional investors, all of whom become shareholders.

Shareholders sometimes express interests different from the purpose for which the business was created. By organizing their efforts—emphasizing executives’ fiduciary responsibility toward them—some shareholder groups have succeeded at influencing business governance and thereby changing the function and form of a business system’s destination, vehicle, and thus its journey. They have also succeeded at replacing executives of whom they don’t approve.

Hence, the difference between a privately owned business and a publicly owned one is the perception of the system’s destination—the system’s purpose and its beneficiaries. When profits are spent on dividends and share buyback programs and are not plowed-back into the business in order to develop the system’s capability and capacity, it indicates a mechanistic perspective on business, whereby satisfying shareholder financial demands is prioritized over customers’ needs.

Any subsequent loss of integrity among the vehicle, the journey, the destination, and their business governance is manifested in the behavior and performance characteristics of the business system as an organic whole, and ultimately in its brand identity, profitability, and market valuation. Dueling destinations—prioritizing service to one’s target audience or to one’s owners/shareholders—is a major source of harmful friction and conflict.

The Environment

You cannot lead a business system, or steer it into another strategic direction if you don’t understand how that business functions as a singular, unique, integrated, and open system. Attempts at changing a system you don’t understand is nothing more than trial and error.

Analysis—the traditional approach to gaining understanding—is, unfortunately, not sufficient by itself. Dividing a whole into its component parts, studying each part separately, and then aggregating what you learned about the parts into an understanding of the whole just falls short. Analysis reveals the structure of a system: how it works. Hence, the product of analysis is know-how. Knowledge is what is contained in instructions, the what and how, better known as best practices. These instructions are often packaged in simple sound bites, buzzwords, and jargon. Understanding, on the other hand, creates insight, which is contained in explanations, the why it works as it works. Insight cannot be transferred in step-by-step instructions, sound bites, or buzzwords because each and every one of those instructions would require an explanation. Understanding is a cognitive process that is different for each and every one of us, but the end result is the same; wisdom—that is, the trait of using knowledge and experience with common sense and insight.

Understanding requires another method of thinking, synthesis, which is a reasoning from cause to effect. Explanations for the occurrence of cause-and-effect relationships are not found within separate parts but in the role or function they perform within the system as a whole. Synthesis reveals those roles and functions, which explains why a system works or behaves the way it does, as it does. While analysis produces knowledge, it is synthesis that produces understanding. Hence, it is synthetic thinking that creates understanding. And the fusion of analysis and synthesis is called systems thinking.

Now, if recognizing cause-and-effect relationships holds the key to understanding, we need to ask ourselves if the cause is not only necessary but also sufficient to explain why the effect occurred. For example, is a factory necessary for building cars? Yes, but is that sufficient? No. It requires raw materials; capital; a workforce that is educated, skilled, trained, and experienced; logistics to and from the factory; electricity; fuel; and so many other requirements. In other words, what is necessary for a cause to provide a sufficient explanation for the effect it creates is known as the environment.

It is the environment in which it operates—the wealth, health, education, consumer preferences, resources, and infrastructure of a country or region—where we find opportunities for a business system and its stakeholders to thrive. Note that the environment includes laws on local, regional, statewide, national, international, or supranational levels, which provide (financial and liability) protections, regulations, policies, subsidies, quotas, industry standards, work safety requirements, consumer protection, general trade practices, sanctions, morals, and ethics that cannot fail to influence decisions regarding a corporation’s business governance practices. I will revisit the benefits of a well-functioning environment in Chapter 9, under “Preconditions for Success.”

In conclusion, nothing can be understood independently of its environment. Every law or principle is constrained by the environment within which it applies. They’re all environmentally relative, which explains the intersection between economic theory and politics. A discussion of economic theory and politics falls outside the scope of this book, although I highly recommend acquainting yourself with these topics.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

Having painted a bigger-picture perspective on business mechanics, I have shown how disparate knowledge and information can be compartmentalized over a business system’s journey, vehicle, and destination, in order to be organized and integrated into an organic whole, which is then directed toward the realization of its intended purpose by business governance.

Because a business system is predominantly perceived as an endless chain of buy and sell transactions, we’ll start our exploration into relationships among the component parts of business mechanics by describing the journey.