INTRODUCTION

The Cost of Ignoring the New Rules of Real Value Creation

It’s all a question of story. We are in trouble just now because we do not have a good story. We are in between stories. The Old Story—the account of how the world came to be and how we fit into it—is not functioning properly, and we have not learned the New Story.

—THOMAS BERRY, “THE NEW STORY”

IN 1999, THE NEW YORK TIMES chronicled the egregious behavior of the Royal Caribbean cruise line. The company, founded in Norway but based in Florida, was censored for dumping toxic waste and spent fuel in the Caribbean Sea and US coastal waters, endangering the coral reefs, beaches, and sea life that their customers book passage to enjoy.

Before ships set sail, the waste containment system is inspected, so the dumping was clearly intentional. Dumping spent fuel lightens the load, saves fuel costs, and avoids waste disposal fees back in port. It also endangers the ecosystem and is a clear violation of the public trust. The actions for which Royal Caribbean was censured put both the company’s long-term interests and reputation at risk.

What was the ship engineer thinking? Why risk tarnishing your own brand to save money today?

A TALE OF A SYSTEM GONE WRONG: FROM ROYAL CARIBBEAN TO BOEING

Fast-forward to 2016, when James Robert Liang became the first Volkswagen employee to admit guilt in the company’s rogue program to undermine government emission standards. For Liang and others at VW, the constraints on emissions signaled the need to innovate—not by building a better diesel engine, but by designing and installing software to fake the real emission levels during testing.

The VW story was shocking when it broke, but also mystifying. How long did they expect to keep the deception secret? By the time of Liang’s admission of guilt, the company had already paid out $15 billion in penalties and even greater claims, and lawsuits were piling up in both the United States and the far larger European market.

And Boeing may never fully recover from the deadly consequences of a culture driving too hard toward the bottom line. In April 2020, as the coronavirus roiled the airline industry, Boeing announced that customers had canceled orders for 150 of its best-selling plane, the 737 Max. By then, the plane had been grounded for over a year as the company worked to fix the ill-designed operating system that was linked to two airline crashes—hundreds of lives, and the trust of pilots in Boeing itself, destroyed. The sidelining of those assets resulted in hundreds of flights being canceled each day at the peak of the 2019 summer travel season. A $4.9 billion charge against earnings was just the first step in assessing the cost of the business failure—the opening pitch in the game of blame and valuation of lives lost that will proceed over years, if not decades.

Tell me which of the pressing issues of our time keep you awake at night, and I will tell you how the old rules of profit maximization and short-term thinking contribute to those problems.

Globe-hopping brands with big footprints and deep supply chains and the extensive reach of industry, technology, and commerce touch virtually every aspect of our lives. Climate change is a product of industrial processes. It is a problem with unimaginable consequences that cannot be solved without collective action; it now tops the list of global concerns. We can easily connect the dots between consumers shopping on the basis of price, low-cost labor markets, and the working conditions where human rights violations and even human trafficking persist. The economics of overconsumption and unsustainable growth create boom-and-bust cycles that favor some but push others to the side. Marketing of unhealthy products. Tax avoidance. Obesity. Our infatuation with guns. Food waste. Deforestation. Pervasive inequality and its consequences.

For good or for ill (and it’s both), global business—talent-rich, capacious, and connected—is the most influential institution of our age, akin to the Church in the Middle Ages. Clues to the power of business are found in daily headlines and in politics.

We need a new script.

This book offers a different—and more useful—set of rules that can transform the game of business. And it provides stories about how the game is already changing according to the new rules.

The rules followed by corporations aren’t set in one place, like the Vatican. They emerge from Congress, regulatory agencies, and trade associations. They are set by investors with different time frames and definitions of a fair return on investment (ROI), and by outside activists, internal agitators, and purchasing agents who are under pressure to redefine the narrative about business success. But, ultimately, they emerge from business itself—they are a function of embedded assumptions, decision rules, protocols, and incentive systems that shape intentions and behavior.

Yet, it is also true that the rules and expectations that companies choose to follow are unquestionably tied to the belief that shareholders own the firm and that clarity of managing to a single objective of shareholder value leaves us all better off. The evidence to the contrary is overwhelming, but systems change is hard, especially when the ideology is reinforced by the tenure system in classrooms and myriad forces in boardrooms.

The old rules derive from the power of the shareholder mindset. The new ones are derivative of the change that is enabled when other, more powerful contributors to value creation are revealed. The threads of this conversation about corporate purpose are woven throughout the rules that mark the chapters of this book.

The underlying narrative about the purpose of the corporation, and the practices and mindset that give shareholder primacy its power, are giving way, at last, to the reality that business and society are truly codependent. New, future-oriented sources of power and influence are already affecting the game, and a new cadre of business leaders are redefining business success. Business schools are catching up with boardrooms wrestling with a new road map—one that points the way to new measures of progress and is consistent with the values of the new generation preparing to lead.

THE COST OF IGNORING THE NEW RULES OF VALUE CREATION

The stories of Royal Caribbean, and VW and Boeing, follow a similar line. To dump waste carries some risk, but it is guaranteed to reduce the cost of doing business and keep prices low to consumers. The ship’s engineer was likely rewarded for finding a way to cut costs. The engineers at VW cared about the environment, but the rules and incentives that defined the culture were principally designed to grow market share. Boeing scuttled protocols and silenced contrary voices in the campaign to beat Airbus. Wells Fargo maxed revenues by creating the conditions for account managers to push products onto unwitting customers. Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase created innovative securities for the mortgage market that purported to shield investors from risk (they did not) and helped fuel the housing bubble and subsequent mortgage meltdown of 2008.

And before all of these examples became front-page news, there was Enron, a high-performing stock in the late ’90s that proved to be a house of cards and spectacularly collapsed in 2001.

Enron failed several years into the design of a program I founded in 1998 with a grant from the Ford Foundation to support fresh thinking about the role of corporations in both classrooms and boardrooms. I chose the Aspen Institute, founded by a Chicago industrialist in 1949 and known for problem-solving through dialogue and leadership development, as the program’s home.

A decade earlier, in 1989, I had left a job at Bankers Trust as a lender to manufacturers and importers of apparel to join Ford’s Program-Related Investments division. As the head of Ford’s venture in what today would be called “impact investing,” I oversaw a $100 million portfolio of loans and investments structured to encourage banks and insurance companies, from Allstate to Bank of America, to coinvest in community-based economic development.

My territory at Ford was a big leap from New York’s garment center. I visited US-operated factories in El Paso’s neighboring city Juarez, Mexico, and villages in Bangladesh experimenting with microcredit, as well as US locations from Arkansas to rural Maine to inner-city Cleveland. The globally astute members of the foundation’s board included corporate titans like David Kearns of Xerox, Ratan Tata of Tata Industries, Henry Schacht of Cummins Engine, and Bob Haas of Levi Strauss.

These trustees were at home with the intentions of the program and didn’t question the risks we took. Instead, they posed questions that caused us to consider a peculiar divide between the foundation’s work and its origins. We were investing and spending Henry Ford’s vast wealth without pausing to think about how it had been created.

With seven years of banking under my belt, I understood that at Ford we were working in the shadows of business but without directly considering the private sector’s role and impact on the foundation’s mission of expanding economic opportunity in the United States and globally.

When I began the Business and Society Program at the Aspen Institute, we started by probing the connections between how leaders think about their responsibilities and the attitudes imparted by teaching in business classrooms. It was the heyday of the MBA; rising executives all seemed to come through business schools.

The demise of Enron seemed to happen overnight. It occurred while my colleagues and I were testing a format for dialogue among business leaders that over several years included Ken Lay, the CEO of Enron; and executives from Shell, McKinsey, PwC, BlackRock, General Dynamics, Cummins Engine, and Pepsi. As we headed home to New York from our conference center in Aspen, Colorado, the attacks on the Twin Towers reverberated through the markets and permanently reset our worldview.

The events that followed from the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, and the failure of Enron that fall will always be conflated in my mind. Enron died by a host of decisions that enabled it to dominate key markets and to prop up earnings per share. The old rules of profit maximization that governed Enron enriched some but ultimately failed all of us.

It’s time for a new set of rules.

The old rules paid off, at least for a while. This book is about the changes—the forces that are conspiring both inside businesses and in the business ecosystem—that enable executives to think and manage differently. It is about the consequences for businesses that fail to embrace the new rules, and a new definition of business success.

Sociologists talk about the scripts that guide human behavior—the interplay of intentions and decisions that look obscene when exposed but are, in fact, cultural norms. The engineers and professionals and managers at Enron, VW, and Boeing were not malcontents laying the seeds of the company’s own destruction; they were operating within the protocols of their companies and within highly competitive industries.

Public capital markets are complicit. With all of the attention paid to so-called socially responsible investors, the stock price still falls when a business invests in public goods—for example, when a tech company announces that it is adding jobs; or a drug company spends on R&D without an immediate payback; or a consumer product company, like Pepsi, or a retailer, like CVS or Walmart, reduces its exposure to a product with a profound social cost that contributes a lot to the bottom line. When Pepsi cut marketing budgets for regular soda to make room for “good for you” drinks and snacks, it paid the price on Wall Street. In chapter 3, we see that Pepsi ultimately gave in to these pressures but continued to build a portfolio of healthier products for which it is also known.

The playing field is complex. But the corporation itself is not moral or immoral—it is not good or bad like a person—rather, the decisions made by the company are what have good or bad results. And the decisions are a function of the rules and incentives and metrics that influence behavior in the executive suite and on the shop floor. The rules are set by leaders—they reflect what the leaders believe to be true and what they value. To move the needle on the problems that keep us awake at night, to break this vicious circle, we need to change how business leaders—and their counterparts in finance—think and act.

In the early 2000s, in the wake of Enron’s demise, the highly respected dean of the Kellogg School of Management, Don Jacobs, announced a new screening process to weed out the “bad apples” before they enrolled. But we don’t fix the system by closing the gates at Kellogg or Harvard, or by sending midlevel engineers from VW or top executives of Enron to prison, as necessary or satisfying as that may be. We need to unravel the rules of the road under which the decisions of the executives of Enron—and a host of players revealed since—make sense.

The first step is to look deeply into the business system and how the core assumptions and dominant beliefs—the mindset of the executive—are shaped and reinforced and in turn shape the incentives for the middle managers, the engineers, and the CFOs.

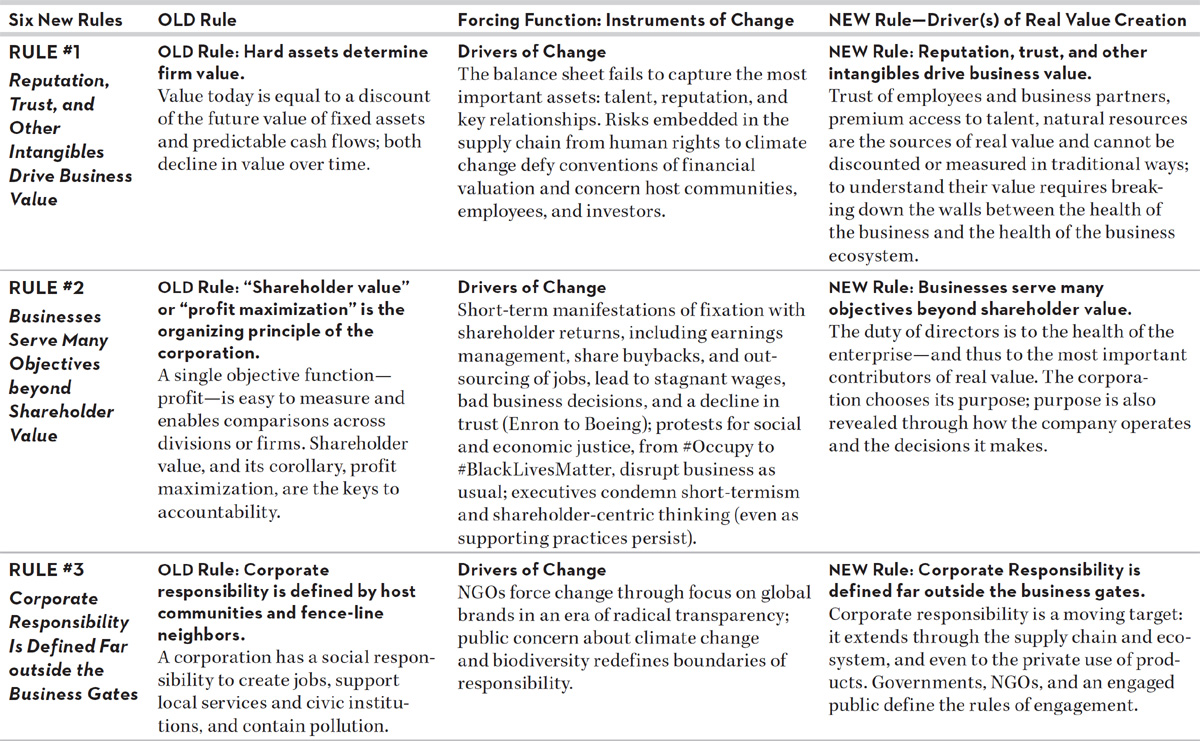

NEW RULES: REAL VALUE

Chapter 1 examines the first of six new rules that are already influencing these assumptions and the conduct of business. Behind Rule #1 is the growth in intangible forms of value, from employee know-how and loyalty to a firm’s reputation and license to operate. These assets are difficult to measure and upset traditional valuation formulas and measures. The measurement of real value connects the company to the natural and human ecosystem on which it depends: the consequences of decisions today on future generations cannot be discounted. Embedded in the understanding of future value—real sustained value—are risks that are easy to ignore today.

Chapter 2 explores the profound shifts taking place as the organizing principle of “shareholder value” gives way to common-sense management behind Rule #2—the reality that companies naturally serve many different objectives in order to flourish. Decades of probing both theory and practice in the work of Lynn Stout, Marty Lipton, Ira Millstein, Lynn Paine, Leo Strine, and other important voices have succeeded, at last, in disrupting the belief that corporate law, aka the laws of Delaware, where many public companies are incorporated, requires public companies to manage the company as if the shareholders own the enterprise itself, rather than shares of stock with specific rights.

These new rules pave the way for business decisions oriented to the future. Importantly, these new rules depend on forms of corporate accountability proving to be more powerful than adherence to shareholder preferences.

Yet, two decades after Enron’s implosion, we are still experiencing the consequences of decades of teaching, as well as the strategic advice aimed at profit or share price as the principal—even single— objective of a well-run business. The old rule of profit maximization is giving way to more critical measures of real value. It is also true that the scaffolding that supports the shareholder mindset is still firmly in place.

The purpose of the enterprise is determined by the board and executive, but, importantly, it is also revealed in how the leaders act— in the choices they consider.

Assumptions and incentives that underpin shareholder primacy have developed a language and narrative of their own. Statements like “pay for performance” and “maximize shareholder value” are spoken as if they were handed down with the Ten Commandments. The drumbeat about shareholder primacy, and performance measures such as total shareholder return (TSR), feed short-term-oriented investors at the expense of employees, stewardship of natural resources, and constructive engagement with host communities.

These inputs are the source of real business value.

Adam Kahane, author of Solving Tough Problems: An Open Way of Talking, Listening, and Creating New Realities, facilitated our first Business Leader Dialogue as the seeds of Enron’s destruction were being revealed. Adam uses a form of scenario planning he learned at Royal Dutch Shell to build the will for change in difficult environments. He would start our dialogues with the following thought: “The system is perfectly designed for the result we have now—if we want a different result, we need to rethink the system.”

As classrooms and boardrooms move to a more coherent and useful conception of fiduciary duty, new questions emerge:

• Can we design companies to be less vulnerable to the demands of capital market actors who operate at a remove from the long-term consequences of business decisions?

• Can we embrace decision rules that balance short-, medium-, and long-term focus; that prioritize the needs of real investors over traders, respect the constraints of natural resources, and treat employees as an asset rather than a cost?

• Can we rethink the incentives and decision rules that govern behavior?

The demand for new measures of business success is heard from Main Street to Wall Street. The new rules of the road are already engaged and are anchored in changes taking place in executive suites, boardrooms, classrooms, and employee networks.

What is needed now is to pick up the pace of change.

Values we take for granted in private, founder-led or family firms with consumer brands like Eileen Fisher, Patagonia, and S. C. Johnson are also finding footing in massive, globe-hopping, publicly traded firms. We see the effect of fresh thinking in the bold move by CVS to stop selling cigarettes, in Pepsi and Coke’s decision to drop its membership in the plastics industry association and rethink packaging, in Google’s pledge to pay a minimum of $15 per hour to contract laborers, and in Shell’s decision to quit the US oil lobby and join a growing number of companies committed to aggressive reductions in their carbon footprint.

In each case, we are invited to go deeper, to better understand the motivations and the business model that sit behind the actions—to ensure that these claims and goals signal fundamental change rather than examples of greenwashing. Yet in each example we also see the impact of external and internal forces driving the change and observe a shift in attitudes at the helm.

The forces of change behind the new rules are compelling. They call on our most basic human instincts and align with growing understanding of our dependence on healthy ecosystems and communities. These stories reveal new forms of accountability and inspire fresh thinking about the role and purpose of business. They clarify what is needed now.

In chapter 3, we explore Rule #3 and how actors like Jason Clay of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and his peers at Oxfam and Greenpeace employ social media and mine the connections in supply chains to radically redefine and expand the responsibilities—and potential—of brands. In chapter 4, which is concerned with Rule #4, we delve into how the same tools are deployed by employees, inspired by #MeToo, #GoogleWalkout, and #BlackLivesMatter, to give fresh voice to business risk, expand the horizons of business leaders, and rethink the relationship between business and its workers.

Chapter 5, which addresses Rule #5, focuses on financial capital— and how the reality that capital is abundant, not scarce, is reshaping the culture of firms.

New norms of behavior explored in these chapters are evident in newly capitalized companies and are propelled by social networks that link employees with environmental activists and worker organizations. The new rules of engagement challenge the centricity of financial capital and the dominance of public capital markets.

We see the new rules in questions about capital allocation and the “talent strategy” in the executive suite. We can see the change in the 2019 decision of the Business Roundtable—a CEO-only member organization representing many of the largest American companies, the voice of big business and industry in Washington—to rewrite its own mission statement to better reflect the aspirations of many US business leaders. The new rules support the 2020 manifesto on regenerative capitalism declared at the World Economic Forum in Davos. They will help set priorities as we weather and eventually emerge from the COVID-19 crisis and, at last, step into the challenge of addressing the structural underpinnings of both racial inequality and climate change. And, importantly, new definitions of business success have already begun to crack mainstream business classrooms where the story of shareholder primacy began and is still in force—classrooms that orient the analysts at Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley and the new recruits at McKinsey and BCG and Deloitte.

The new rules influence—and are influenced by—the change agents who operate within business or challenge it from the outside. They offer a response to withering critiques of capitalism and the decline in trust in business as an institution. The endgame is to secure the remarkable capacity of business to move the needle on socially and environmentally critical goals.

Nitin Nohria writes about leadership. On becoming dean of Harvard Business School, he wrote about the importance of the business sector and private initiative to make any real headway on our most consequential problems—from environmental sustainability and climate change to poverty and fixing the health care system.

When business hangs back, we lose our core capacity to invest in our future. Disheartening examples of business on the sidelines include the failure of business trade groups to organize around a coherent policy on climate change and the choice of many public companies to spend the 2018 tax cuts on share buybacks rather than investing in our economic futures, through the workforce and infrastructure.

What will need to be true to harness business capacity for the work of the world? The interplay of citizen-and employee-activists; unusual leaders; and business-led, socially useful innovations is the juggernaut of change and helps us understand how change takes root and grows. What’s needed now is to pick up the pace of change that new rules enable—to separate real value from ephemeral, backward-looking measures of financial value.

And importantly, when the system itself is a risk, when markets are on the path to extinction, we see that value creation requires collaboration and co-creation to stabilize conditions, expose the source of the problem, and redesign the business model.

Chapter 6 explores Rule #6, which is about the path to co-creation, the practices and protocols and playbook that ultimately raise the bar across an industry and assure widespread adoption of new business models. Sometimes the chief architect is the brand with the largest exposure to threat. Often, the change requires a trusted broker from outside industry, a curated coalition of like-minded producers, and a client or customer willing—or forced by necessity—to take a long-term view and work to align the market with the limits of growth and new definitions of value.

I hope this book helps business leaders—but also NGOs and foundations—to think deeply about their role as change agents and how critical these new rules are to the future of business and sustainable markets. I hope it illuminates the old norms and governing rules that hold them back. I hope the book strikes a chord with individuals who seek change but are still focusing on rearranging the deck chairs rather than setting an entirely new course of action. I hope the stories make the change visible and accessible—and help put the old rules of value extraction out to pasture. I hope the story of change demonstrates what is possible now.

Decades of work by scholars and campaigners and like-minded business leaders are paying off. The new rules now need air, voice, scholarship, and practice. In chapters 7 and 8, we look at the road ahead, and how the new rules especially need to be seen and understood by the old rule enforcers—strategy firms and investment banks and compensation consultants and accountants and scholars who keep the status-quo-enhancing decision rules alive.

In chapter 7, we take a closer look at systems design, especially the role of incentives and rewards for executives. The massive shift toward equity-based pay that began in the 1980s produced runaway CEO pay and a premium for stockholders at the cost of employees and long-term investment; it sends signals that directly undermine the new rules and the urgent call to CEOs to lead on issues of consequence for both business and society. The CEO matters; how she thinks, or what he values, are a critically important starting point for change. We need to redesign pay to catch up with the intentions of executives to serve society.

In the last chapter, we return to the role of teachers in business schools who are catching up in important ways and unleashing new talent—but there is more to do. We especially need to crack the finance classrooms that keep the medieval ways of shareholder-centric thinking in place and reinforce the old story. They respond to the recruiters from financial and other professional services that are still tightening the screws to old specs. As Thomas Berry says, the Old Story is not functioning properly, and we have not learned the New Story.

Enterprises that operate in the give and take of global markets have the power to translate small changes into influential, industry-scale protocols. In incremental but important acts, through the power of small but influential groups that are embracing co-creation over race-to-the-bottom competition, we have begun to see a shift in what constitutes a high-quality business decision that stands the test of time.

The new rules are already written. The forcing mechanisms described in this book and summarized in the chart that follows this introduction give them staying power. Change agents both outside and inside the enterprise are rethinking protocols and decision rules for investment and business strategy.

It’s time to play by the new set of rules.

NEW RULES: REAL VALUE

![]() OLD RULE

OLD RULE ![]()

Hard assets determine firm value.

Value today is equal to a discount of the future value of fixed assets and cash flows.