PART TWO

Personality Type, Brain Dominance, and the Creative Process

Coming up soon are forty strategies to help you generate song concepts. But first, we'll take a look at the source of all your creativity—your thinking style. The objective: Whole-brain writing.

What do I mean by whole-brain writing? Simply that the ideas and images supplied by the “creative” right brain have been shaped and edited by the structural left brain into a unified lyric. A first draft often delivers less than its promised potential. Virtually all of the more than one hundred lyrics that will illustrate the upcoming strategies went through several revisions before they could appear on the printed page as “role models.” But lyrics, after all, are not produced whole from an automated machine; they evolve in stages from a cerebral process.

This chapter will give you a clearer picture of the creative process in general and your individual process in particular. First you'll identify your “type”—that is, your natural style of behaving and thinking—by means of a short questionnaire: The DPS (Davis Personality Scale), a personality assessment instrument based on Carl Jung's theory of Psychological Types. Then we'll examine your type in relation to your songwriting style.

Although every brain is unique, members of each type group tend to produce writing that shares characteristic strengths as well as characteristic potential weaknesses. Armed with this new awareness of how your type/brain dominance shapes your rough first draft, you'll have a much clearer picture of how to achieve a polished final draft.

![]()

Identifying Your Personality Type and Brain Dominance

The short questionnaire on Davis Personality Scale (DPS) that you're about to answer asks you to rate your everyday ways of thinking, acting and deciding—not how you believe you should be or wish you were or how you plan to change, but how you actually behave. The questionnaire is in no way a “test.” There is no right or wrong answer because there is no good, better or best type. All thinking styles are essential to a balanced functioning of the world.

As you read each set of four polar-opposite statements, you may think that the most desired response is a balanced middle ground between two extremes. It isn't. Strong preferences create strong, achieving personalities—an Einstein, a Bernstein, a Hepburn, a Streisand. The objective is to indicate as honestly as you can your preferences—however mild or extreme.

First read each pair of polar opposites. Then on the scale beneath them, mark two (2) Xs, one on each side of the -0- on the dot that indicates where the degree of your preference lies. Be sure to give a preference to one end of the scale over the other, however slight; for example I-8, E-9. I suggest you use a pencil rather than a pen: As you gain a better understanding of type terms, you may want to modify some of your initial responses. Stop reading a minute and take the questionnaire now. After you fill in your four-letter type, I'll define the letters I/E, S/N, T/F and J/P.

What the Letters Mean

Now that you've identified your type, what do those four letters signify? The I/E scale represents two opposite sources of energy—Introverting, that is, being energized from within by reflection; Extraverting, being energized from without by interaction. The S/N scale represents two opposite means of perception—Sensing, knowing via the five senses, or iNtuiting, knowing via unconscious insights. (“N” is used for Intuiting as “I” already stands for Introverting.) The T/F scale represents two opposite means of coming to conclusions—by Thinking, nwhich is objectively based on logic; or by Feeling, which is subjectively based on people-centered values. The J/P scale represents two opposite behavioral styles—Judging, which is organized, purposeful and decisive; or Perceiving, which is unstructured, flexible and open-ended.

Extraverting (E), Introverting (I), Judging (J) and Perceiving (P) are the four attitudes we have toward life; Sensing (S), Intuiting (N), Thinking (T) and Feeling (F), the four functions by which we learn and decide. Because these eight terms are used around the world to refer to Jungian psychological types, I'll be using them throughout the book interchangeably with the capital letters that represent them.

Type and the Brain

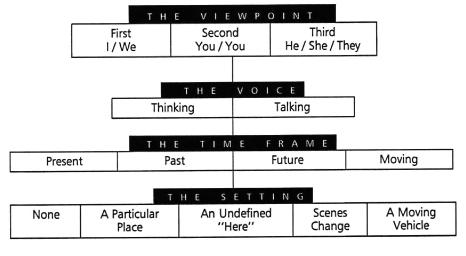

Now let's look at the way that type mirrors brain function. This stylized model points up the distinctive nature of the two hemispheres:

Adapted from Left Brain. Right Brain (1989).

The left has tight, vertical, nonoverlapping cells needed for fine motor movements; the right has horizontal, overlapping and more widely spaced cells needed for visual/spatial tasks. The left brain can be compared to a microscope that provides a closeup of the details—the parts; and the right brain compared to a telescope that provides a broad view of the possibilities—the whole. Whole-brain thinking integrates the parts and the whole.

In the model The Four Attitudes & Four Functions a Symbolic Brain Model, the eight sets of descriptive phrases identify major characteristics of our eight functions and attitudes. Their inherent polar-opposite relationship forms a kind of invisible X: Introverting and Thinking in the upper left cerebral cortex contrast with their opposites, Extraverting and Feeling in the lower right; similarly, Intuiting and Perceiving in the upper-right cerebral cortex contrast with Sensing and Judging in the lower left.

First read the two descriptive lists vertically to gain a sense of the distinctive nature of the two hemispheres: your literal, logical, sequential left brain, in contrast to the imaginative, visual, holistic right brain. Then, to better appreciate the antithetical nature of the four pairs—I-E, S-N, T-F and J-P, compare the descriptions of each pair by reading them alternately line by line.

| THE FOUR ATTITUDES & FOUR FUNCTIONS A SYMBOLIC BRAIN MODEL | |

|---|---|

| The Left-Brain Microscope | The Right-Brain Telescope |

| Introverting (I) Private/reflective Focuses energy inward Interest in concepts Develops ideas alone Requires reflection time Considers before answering Sets own standards Seeks underlying principles | Perceiving (P) Inquiring/flexible/open-ended Broad vision/approximate Follows the flow Juggles multiple projects Works spontaneously/needs freedom Mindless of time Energized at last minute Resists closure |

| Thinking (T) Impersonal/objective/just Analytical/critical Challenging/questioning why Values clarity/coherence Logical/reasoned Detects discrepancies Seeks meaning Cause/effect thinking | Intuiting (N) Imaginative/insightful/theoretical Figurative/visual/abstract Innovative/future oriented Changing/radical Recognizes patterns Sees the big picture Wonders “what if?” Enjoys independence Synthesizes Random/amorphous |

| Sensing (S) Realistic/practical/factual Literal/syntactic/concrete Traditional/present oriented Consistent/conservative Matches by function Sees the small detail Makes statements Breaks into parts Sequential/structured | Feeling (F) Personal/subjective/humane Accepting/appreciative Accommodating/agreeable Values empathy/compassion Persuasive Sees similarities Seeks harmony Enjoys affiliation Value-based thinking |

| Judging (J) Organized/industrious/decisive Narrow focus/precise Follows a schedule Deals with one thing at a time Works from lists/plans/goals Time conscious Completes tasks early Seeks closure | Extroverting (E) Sociable/active Focuses energy outward Interest in people/things Develops ideas in action Plunges into experience Readily offers opinions Needs affirmation Avoids complex procedures |

As this model suggests, you possess all these qualities which you use in varying degrees every day, both consciously and unconsciously. Taking the DPS you discovered that you tend to use one of each pair of opposites more than the other, thus creating your type/brain dominance profile. That profile can range from an all-left or all-right preference–ISTJ and ENFP respectively–to fourteen other types whose preferences are split between the two hemispheres. Now that you have a better understanding of what the letters I, E, S, N, T, F, J and ? represent, I recommend that, before moving on, you look back at the DPS to see if you want to modify your ratings on any of the four scales. A slight shift in preference could change your type.

Visualizing Your Type and Cognitive Style

On two models that enable you to visualize your mental process. The first shows how the eight attitudes and functions relate to general areas of the brain. The second illustrates the four cognitive styles: the cerebral dominant Intuitive/Thinker (NT), the right dominant Intuitive/Feeler (NF), the limbic dominant Sensing/Feeler (SF), and the left dominant Sensing/Thinking (ST). (The term “limbic” comes from the limbic system, the ancient part of the brain under the cerebral cortex).

When you feel confident about your DPS results, you're ready to envision your four-letter type and your two-letter cognitive style as they function in your brain. Shade in the four wedges representing your four favored attitudes and functions with a colored pen or pencil, leaving your four less-favored wedges blank; then shade in your cognitive style–NT, NF, SF or ST.

As we begin to discuss the creative process in terms of right-and left-brain function, you'll be better able to “picture” your individual thinking style at work.

WrapUp

Rest assured that every type can and does write successful songs. Though you share common characteristics with other members of your type, you are unique. And it is your uniqueness that you want to develop to the utmost.

![]()

Tracking the Four-Step Creative Process

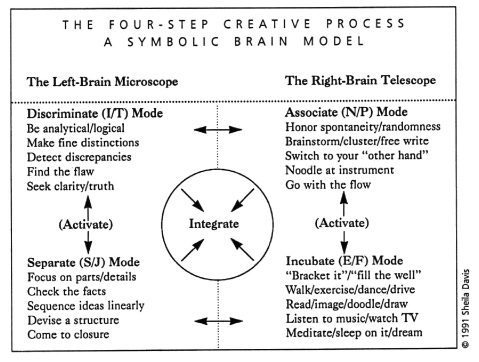

Experts in the burgeoning field known simply as Creativity suggest that it's a multi-step process. I've identified the four steps as Associate, Incubate, Separate and Discriminate. How we activate the songwriting process, and in what order we proceed, seems to be a matter of our type. Naturally, what counts is the destination: A whole-brain song. You can activate the process in either a right-mode or a left-mode way.

To Activate–The Right-Mode Way

We've all experienced that sudden insight that arrives unbidden while showering, walking, driving: Motion appears to put the right-brain into gear. Some songwriters choose to activate the process with such activities as free writing, doodling, or noodling at an instrument. This gives the storehouse of unconscious images and insights a chance to rise to the surface of the conscious mind.

It's as Randy Travis says, “I just pick up a guitar and sing till I hear something I like …” Lyricist Billy Steinberg clearly values his unconscious, “I try to write without thinking. When you're on the phone, do you ever doodle on a pad and draw strange things that you aren't consciously thinking about? This is much like how I start my best song lyrics.” Mike Stoller of the fabled team of Lieber and Stoller described the collaborators'approach, “It was like spontaneous combustion.… I would just play riffs [at the piano] and Jerry would shout lines, almost like automatic writing.”

To Access the Right Mode: Be physically active. Noodle at an instrument. Doodle on a pad. Extravert: Verbally brainstorm. And honor the random.

To Activate–The Left-Mode Way

Other writers prefer to start the process with a concrete “part” and work from the part to the whole. Michael McDonald, for example, likes to rhythmically structure: “I usually write around a certain melodic rhythmic figure that is going to be the bottom theme of the song. Everything is an offshoot from that.” Comedy writer Dave Frishberg finds his structuring element in a newfound title: “I start out with a title and premise and then try to map out the scheme of what will happen in the lyric. I plan how I will arrive at the punch line or the climactic lyric moment and then construct the lyric to make it happen.” (emphasis mine)

To Access the Left Mode: Think “part.” Narrow the options. Choose a title or motif or chord progression. Devise a structure. Work step by step.

To Associate -A Right-Mode Step

When the lyric concept or music motif has announced itself, unconsciously, or consciously, let it expand, that is, let it connect to other random thoughts and sounds. For example, Tom Waits says, “Sometimes I'll turn on the tape recorder and start playing, just making up words before I have any words.… I'll [even] do it in Spanish, anything that makes a sound. Then I'll listen to it and put words to it.” That's free associating! Paul McCartney summed up the Beatles'right-brain process by admitting, “There's a lot of random in our songs … writing, thinking … then bang, you have the jigsaw puzzle.”

To Access the Associate Mode: Be spontaneous. Brainstorm for related lyrical ideas and/or rhymes allowing words to connect without censure. Let your music flow freely. Resist closure.

To Incubate–A Right-Mode Step

Sometimes the first associations fail to fuse. Creativity can't be rushed. Your concept may simply need incubating time. This step in the process can be enhanced by meditation or movement: Veteran lyricist Mitchell (“Stardust”) Parish told me, “Once I had the title, I'd walk around with it for a while to let it percolate.” Richard Rodgers claimed, “I usually get the approach sitting in a chair or walking around outdoors. Then I'll do the tune on a piece of paper or at the piano.”

My teaching experience has verified that many writers start to write too soon–especially J-types: In their hurry to come to closure, they may zip past this essential step. The first draft shows it: The lyric's all surface and no depth. Not enough time was taken to create a believable situation and develop a genuine character who feels a real emotion. We hear rhymes without reason. I encourage you to believe that the more time you spend incubating, the less time you'll spend revising.

To Access the Incubate Mode: Walk around with it. Imagine. Become the character. Feel what the singer's feeling. Sleep on it.

To Separate–A Left-Mode Step

After the initial “aha” and the whoosh of associated ideas comes the separating process, both musically and lyrically. After incubation, shift to the left-mode to structure ideas, determine the form, to separate into parts–verse/climb/chorus/bridge and so on. Stephen Sondheim consciously practices the separating process: “I write on legal pads in very small writing … I find it very useful to use a separate pad for each section of the song.“Then comes the winnowing down process of ‘how much can this song take?’ You can make points, A, B and C, but you don't have room for D, E and F. As you do that, you eliminate certain colors and it becomes more apparent what the song should be about.”

Separating also embodies contrast: Cynthia Weil told me, “In a bridge I try to say something I haven't said before–taking the story one step further.” Discussing musical form, Jimmy Webb suggests, “The chorus should always have a different melodic and chordal character than its verse … Sometimes it is advisable to modulate the end of a verse to a different key–often high–to set up the chorus.…”

To Access the Separate Mode: Break into parts. Contrast the parts. Sequence ideas. Put causes before effects. Solidify rhyme scheme and meter.

To Discriminate–A Left-Mode Step

And last comes discrimination, that essential of all art–making fine distinctions. By accessing our helpful critical editor, we can detect the flaw, prune the redundancy, revise the awkward phrase, and thus transform a mediocre first draft into a marvelous final. Johnny Mercer clearly enjoyed this part of the process, “I type dozens of alternative lines. And I look at these alternatives, and I gradually weed out the poor ones until I think I've got the best lyric I can get.” Rupert Holmes asserts, “The biggest part of being a good lyricwriter is learning to be a good editor.” John Prine agrees, “You don't write, you edit.”

To Access the Discriminate Mode: Seek clarity. Unify the time frame, voice, viewpoint and tone. Distinguish figurative from literal. Perfect the syntax.

The Ongoing Process

That's just the first go 'round. Your song, of course, needs a response from an audience. Then, after some critical feedback, the revision process will again spiral through discriminate/separate and yet again, incubate/discriminate and on and on until you feel 100 percent satisfied that you've polished the lyric to its ultimate best.

WrapUp

As you begin to relate your process to your type, you may understand why you find some steps more enjoyable than others. (As do we all!) Perhaps you'll even want to try a different mode of activating a song. Though you may have a favorite “system,” trying it another way will help you increase the creative flow.

![]()

How Your Type Influences Your Work Habits

Every aspect of your type influences your songwriting in some manner. Here we'll examine how your primary source of energy, E or I, affects the collaborative process and how your favored decision-making style, J or P, influences your work mode–when, how often, and maybe even how much you write. A few guidelines will suggest how to get the best out of your personal style.

Extraverts, Introverts and Collaboration

The Extraverted Style

Extraverts thrive on face-to-face collaborating because conversation (for them) stimulates the flow of ideas. E's often don't know what they think till they hear themselves say it. Siedah Garrett characterized the E preference when she admitted, “My reason for co-writing is that if I sat down in a room by myself, it would be quiet for a very long time!”

An E-Guideline: Try to structure your writing time so that it serves your energy needs. Voice-activated extraverts, for example, can benefit, when alone, from taping themselves talking aloud as they move around the house, or walk or drive, and the natural E-avesdropper would be wise to travel with a pocket pad for converting those overheard one-liners into hook choruses.

The Introverted Style

Introverts, on the other hand (or brain), do their best thinking in private: Dean Pitchford, in discussing his work habits with collaborator Tom Snow said, “Tom and I each happen to do our best work alone and we spend very little time together in a room.”

Introverts–who in this country are outnumbered three to one–tend to feel shy about saying that they work better by themselves, as if it were a flaw. But, introversion, like red hair or black eyes, is a natural genetic alternative, not an anomaly.

An I-Guideline: So Introverts, honor the fact that you require, for your best writing, to write apart. Seek composers who similarly like to write a tune or set a lyric without any distractions. Respect your natural style and make it work for you as it works for Pitchford and Snow (and worked for Rodgers and Hammerstein).

The J/P Polarity and Personal Work Habits

Your preference for either the J or P style tends to predict how and when you write best. Time–oriented, routine-loving J's often set up a regular writing schedule. Fred Ebb–of the Broadway team of Kander and Ebb–said: “Johnny Kander and I work daily from ten to four. Even when we're not working on a specific project, we still work daily on whatever comes to mind.” J's are often self-described “morning types”: Alan Jay Lerner claimed, “I never begin a new song at any time of the day other than early morning.”

The right-brain counterpart, P's, find schedules confining: Kim Carnes says, “I'm not a nine-to-five writer who can sit in a room and say, ‘Hey, we're gonna write today!’” P's prefer spontaneity and flexibility and tend to work best in a last-minute burst of energy. Cole Porter (clearly an EP) said: “I have no hours. I can work anywhere. I've done lots of work at dinner sitting between two bores. I can feign listening beautifully and work. That's the reason I like to go out!”

A J/P Guideline: Remember there's no right or wrong or better way. Honor your way: Try to identify the pattern of your creative needs and arrange your work sessions-structured or spontaneous-for your optimum creative output.

Type and Writer's Blocks

Virtually all writers have experienced that frustrating moment when they can't find the right rhyme or line or chord. With luck, it passes quickly. Then there's another kind of extended fallow period when we fear we may never come up with another idea. Both are instances of that ancient bugaboo known as writer's block. But both can be avoided as you learn to sense when the right brain is the wrong brain-or the left brain is the right brain.

The Temporary Block: The Causes and Solutions

Too Narrow a Focus-A J-Mode Left-Brain Block: Because J's like to stay with a task until it's completed, they doggedly sweat out a block (and in the process make themselves miserable): Diane Warren confessed, “I'll have the whole song almost done and I'll need one line at the end of a bridge or something. Logically, I should just walk away and take a drive.… But I'm a masochist … I'll work three days on that one line and it drives me nuts!” If Diane had heeded her (right-brain's) message and headed for the freeway, she'd have probably gotten the needed line before reaching the corner-and had three days to write another three hits!

Similarly, Marty Panzer admitted to me how self-defeating it is to stay in a stuck place, “Sometimes I'll sit with pencil and paper in hand, and ten hours will go by and nothing will happen. And finally I go shave and while the radio is playing and my mind is on a hundred other things, the one line that I've been trying all day to get will come right to mind.” That's how the resourceful unconscious works when given the chance.

The trick is to become aware of where in your brain you are. Whenever you get that stuck feeling, it means it's time to shake up the neurons a little: You've stayed too long in a left-mode close-up on apart when you need a wide-angle look at the whole. The flexible Ps take a more spontaneous approach when they feel blocked: Carole King suggests, “Get up and do something else. Then you come back again and trust that it [whatever's missing] will be there.” “Trust” is the key. And that technique is called “bracketing.”

Bracketing-A Right-Mode Incubating Solution: In bracketing, you say to your uncooperative left-brain, “I'll put a bracket around that [line], [chord], [rhyme]”- you name it-“I'll move on, and come back to it later.” Bracketing suggests that you trust your process, that you know that the missing word or note awaits at a lower layer of consciousness, and that if you just relax, it'll eventually bubble to the surface. And that's exactly what it does. Smokey Robinson summed the P-bracketing approach, “If the song isn't flowing in the right direction, I'll just put it down; don't try to force it.” (Italics mine, and pun intended).

Sleep on It-A Right-Mode Incubating Solution: Like bracketing,'sleeping on it'can be considered a significant aspect of the right-brain incubating mode. It gives the creative process something essential that it needs. Sting, who as we know from his hit album, Synchronkity, is a follower of Jungian theory, commented, “Original ideas begin in the unconscious.… Our logical minds are in compartmented boxes, and those boxes are disturbed when one is asleep … and [when we're] not being logical, an idea can flow from one rigid box into another.…”

The extraordinary insights and creative inspirations that have emerged while the mind is presumably asleep have been well documented. Composer Burton Lane, in discussing the genesis of “When I'm Not Near the Girl I Love,” told me, “I dreamed that tune.” The previous day he'd been trying to come up with a melody to Yip Harburg's title, but had been unsuccessful: “A tune woke me up in the middle of the night … but I didn't connect the melody then with that title. And that wasn't the first time it's happened. Many times it will come out and I don't realize that it's a tune for the thing I've been thinking about!”

An Overload of Options: The Right-Mode Block

Just as intensive concentration on a problem can cause a left-brain jam, extensive openness to the possibilities can cause a right-brain overload. P-types often suffer from right-brain mental clutter (as evidenced by their paper-strewn desks and overstuffed files). Because they're adept at seeing alternative solutions, they sometimes find it difficult to sort through all their treatment options for a given lyric or melody and come to closure on one.

Organizing-The J-Mode Separating Solution: A P-mode overload requires a J-mode solution: A shift to the organizing area in the lower left brain for sorting out and winnowing down. It means spiraling back to the Separate process. So P's it's time to neaten your desk, answer your mail, alphabetize your files, weed out your ideas, narrow your options-and choose one.

A Different Kind of Type-Caused Block

Sometimes writers feel that their creative juices have simply dried up. This is another kind of block caused by an aspect of our dominant function. Each type seems to produce its own characteristic self-limiting injunction that cuts down on productivity: The intuitive can get blocked by a need to be original; the feeling type by an excessive fear of boring or not pleasing an audience; the sensate by an overzealous focus on the mechanics of writing and doing it “right” and the thinker by a goal to come up with an important or “great” song. Becoming aware of your own self-critical inner voice can help you to purposefully countermand it. Why not stop reading for a few minutes to think about any unfinished songs you may have. Can you identify why you haven't finished them? Mull it over. Then think of some recent top-ten records that you consider unoriginal, boring, imperfect, and less than “important” songs. Might it be worthwhile to give your unfinished lyrics another look? Possibly they've had all the incubating time they need and are now ready to be brought to life.

Filling the Well

Every outpouring requires an inpouring: The creative well needs to be filled up periodically in order to have something to draw from at writing time. A few sources of replenishment include reading good literature and poetry; going to films, theater and museums; and, of course, listening to a wide range of musical and lyrical styles. Consider, too, that taking a walk, watching TV, and chatting on the phone are not “goofing off,” but rather a necessary (incubating) break in the creative process.

Honor your favorite way to fill the well, or try a new one. Yip Harburg said, “I do something physical-walk, hit a golf ball around, go to the zoo.…” Franne Golde suggests, “Go see friends, read the newspaper, go to the beach. You got to feed yourself.” Valerie Simpson offers a thought you might want to pin on your wall: “If you don't try to force it, a song will find the proper moment to come to life.” Exactly.

WrapUp

Here's a brain model that helps you picture the four modes of the creative process-associate, incubate, separate, discriminate–and suggests some ways to access each. (You'll find detailed descriptions of the right-brain techniques on Bight-Brain, Left-Brain Techniques: Defining Our Terms–34.)

![]()

How Your Type Shapes Your Lyrics

Just as your favored attitudes (introversion or extraversion) tend to shape your work style, so do your favored functions (sensing or intuition and thinking or feeling) tend to shape your language style. Here are the major ways in which the functions combine to effect a first draft-along with some helpful hints on how to revise the flaws-or better yet, to avoid them. As you might surmise, the revision generally requires tapping the function that is the polar opposite to your favorite.

The Sensing Style

Common Characteristics: Because sensates are here-and-now realists with acute powers of observation, their lyrics often embody names, numbers and places (“Do You Know the Way to San Jose?”/“99 Miles From LA”); are set in the present tense (“Piano Man”); and are made memorable with small concrete details (“Chestnuts roasting on an open fire”).

The Sensate/Thinker (ST) tends to write from an objective distance with a clearly structured beginning, middle and end (“It Was a Very Good Year”). STJs often exhibit a dry wit and satiric flair (“It Ain't Necessarily So”). The Sensate/Feeler (SF), more than any other type, is given to story songs (“16th Avenue”/“Taxi”). Conservative SFJs tend to express society's traditional values (“Easter Parade”/“God Bless America”).

Potential Problems and Solutions: Because sensates like to do things “the right way” and believe “rules” were made to be followed, some may adhere too strictly to their chosen rhyme scheme, rhythm pattern and song form, producing a possible singsong monotony. Regarding rhythm, S-types benefit from a reminder that songs are made up of sound and silence: cutting out padded words like just, very, really will create more space for holding notes; rhythmic monotony can also be eliminated by consciously varying the meter from verse to chorus to bridge. The “telegraphing” of a rhyme can be avoided with a little purposeful delay. (SLW, Small Craft Warning–Prewriting Suggestion, provides detailed guidelines and exercises on rhythm and rhyme.)

The Sensate's emphasis on “itemizing facts” can result in a lyric that lacks a clear emotion, point or meaning. For the revision, Sensates will need to access their intuitive perception with its knack for seeing possibilities. An SFJs second draft often needs to explain the implication of a plot that contains a series of factual details without a clear point. Sensates, just ask yourself, “What does my song mean? What message do I want to send? With what universal situation do I want the listener to identify?”

The Intuitive Style

Common Characteristics: Intuitives are imaginative, future-oriented, hopeful thinkers whose language is usually more abstract than concrete (“Imagine”), who like to pursue the possibilities beyond the reach of the senses (“Over the Rainbow”), and are attracted to fantasy (“Yellow Submarine”).

Intuitive/Feelers (NFs) are considered the most “poetic” (metaphoric) of the types. Their lyrics often feature “confessional” revelations (“I'd Rather Leave While I'm in Love”). Idealistic INFJs often write songs that inspire others (“You'll Never Walk Alone”/“Climb Every Mountain”).

Intuitive/Thinkers (NTs) are given to asking questions rather than making statements (“What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?”) NTs are inclined to see the ironic aspect of a situation (“Send in the Clowns”) and to be critical of society's mores (“Who Will Answer”).

Potential Problems and Solutions: Because intuitives (Ns) think in insightful leaps rather than in a step-by-step process, their lyrics may lack a linear ordering of events and omit important plot details. These factors can combine to make their first drafts difficult to follow. NF plots often suffer from a blurring of multiple emotions—where the singer's feelings from both “then” and “now” have not been differentiated. Drafts of ENFPs—whose four dominants all reside in the right (holistic) brain—may especially lack clarity because of the use of fused literal/figurative language, mixed viewpoint or voice, and poor sequencing of ideas. (The right-brain doesn't own a watch!)

Intuitive/feelers will need to spend some time using the left-brain's linear, structured, realistic, sequencing abilities. The NF will benefit from asking herself such questions as 1) Is the singer male or female? 2) Is she or he talking or thinking? 3) Is the singee present? 4) Where exactly are they? 5) What one single emotion does the singer feel? 6) Do I mean “rain” literally or figuratively (as “trouble”)?

Having to focus on small details and think analytically can prove stressful to NFs, but this step in the process is necessary to make their lyrical insights and feelings understood and appreciated.

How the l-E and J-P Preferences Affect Lyric Content

I-E and J-P attitudes not only affect the collaborative process and work habits, they also influence the lyric's style and content.

The I-? Effect: Extraverted lyricists tend to write about interpersonal situations and use the talking voice as though the “you” were present (“Big Shot”/“Gome in From the Rain”). Introverts are inclined to be more reflective and prefer the thinking voice (“Yesterday”/“Gentle On My Mind”).

The J-P Effect: The laid-back, “we'll see” attitude of the Intuitive/Perceptive style is reflected in the lyrics by frequent use of words such as if, maybe, perhaps, someday. Occasionally, a first draft may have the singer indecisive with the listener left wondering, “And so … what's the conclusion?” So N/Ps will then need to give the lyric a clearer, more forceful ending.

Conversely, the lyrics of Js, who like to live by a set of systems, may be studded with words like never, always, should, don't, must, and so on. SJs especially need to be mindful that their fondness for absolutes might render first drafts negative, or dogmatic or preachy. For example, the first draft of an ISTJ (who can be pessimistic) may end up with an overly defeatist conclusion, like “I'll never get over you.” So Js, bear in mind that listeners are more drawn to a character struggling to overcome adversity-as in “I'm trying to get over you”-than to one who's given in to despondency.

ESFJs can have a tendency to exaggerate emotions-confusing overstatement with depth of feeling. They may also create “stereotypes” rather than believable characters. The cure: Spending more time in the introverting/intuiting mode to ponder what a real human being would feel and say and do in the plot situation. This will result in a more credible revision. WrapUp

Warpup

The post-first-draft challenge to all: Clarify amorphous emotions, augment sensate facts with insightful meaning, put events in linear order, come to a clear conclusion, and avoid preachiness. As the role-model lyrics will make evident, every type has the ability to do just that and thus turn out successful final drafts.

![]()

Bight-Brain, Left-Brain Techniques: Defining Our Terms

In the upcoming strategies, you'll practice various right- and left-brain exercises and techniques designed to help you switch hemispheres at will. Here we'll define the most significant brain shifters.

Right-Brain Shifters to Access “The Whole”

Free Associating/Brainstorming

These two terms are virtually synonymous. Essentially, they draw upon the right-brain's ability to see similarities and to make the odd connection. Finding the unsuspected link has been called the key to creativity. A quality that facilitates random discovery is a spirit of playfulness, a willingness to “goof around.” Brainstorming requires suspending our left-brain editor in order to let the right brain do its thing-free associate. So we'll be goofing around.

Imaging

The ability to image plays a significant role in the process of creativity. Many creative thinkers have held that images form the matrix of thought. Although people differ greatly in their ability to produce images, the skill can be facilitated by solitude and relaxation-and baroque music. (More on that soon.) Accessing the right-brain's images and then putting them into words helps bridge the two hemispheres. Research studies have provided extensive evidence to support the theory that developing the skill of producing mental pictures develops mind/brain power.

Clustering

Clustering is a right-brain prewriting technique popularized by Gabriele Lusser Rico in her important book Writing the Natural Way. I recommend clustering as a way to generate ideas that reflect your true concerns. Clustering is a form of brainstorming on paper-letting uncensored ideas radiate from a central “nucleus” word or phrase. Through free association, it draws upon random thoughts and stored experiences. (For a picture of the process and examples of the results, see SLW, Comment–Part Six.)

Free Writing

The process of free writing enables an uninhibited right-brain flow of thoughts by requiring the pen or pencil to stay on the paper without the inhibiting “lift-up pause” caused by analytical thinking. By keeping your writing instrument moving, the mind can-for a two- or three-minute period -let randomness take the initial thought wherever it might want to go. This technique can prove useful in providing spontaneous associated ideas on your song topic before you actually start the lyricwriting process.

Other-Hand Writing

In The Power of Your Other Hand, author/artist Lucia Cappacionne offers an effective means to access the unconscious level. In the coming strategies, I will occasionally suggest that when stuck for a line or a phrase, you transfer your pen or pencil from your dominant (writing) hand to your nondominant hand. Your writing may look messy, but the potential discoveries that can result more than compensate. Since brain researchers have suggested that we enhance our ability to crisscross the hemispheres through ambidextrous activities, using your “other hand” may yield additional dividends.

Left-Brain Shifters to Access “The Part”

Systematize/Compartmentalize

To access your step-by-step organizational S/J mode: Make lists, organize your lyrics in alphabetical or chronological order, review your agenda, schedule appointments. In other words, break elements/problems into their component parts and think sequentially.

If you're working on a new lyric, examine each section and ask yourself: 1) What information does the first verse convey? 2) Does the second verse say something new? 3) Does the bridge use a strong contrast device and add more new information? 4) Does the title summarize the essence of the lyric?

Analyze/Criticize

To produce a whole-brain lyric, the final step, Discriminate, is arguably the most important. Developing your thinking function requires sharpening your critical faculties: the ability to discriminate between literal and figurative, to identify a mixed metaphor and unmix it, to recognize and weed out redundancies, to revise poor syntax.

A good way to get yourself into the Introverted/Thinking ?/T mode is to analyze a hit lyric. Choose one from a favorite cassette or CD. But because listening to music engages the right brain, which for analysis is the wrong hemisphere, don't play the record: Read the lyric. This is not the time for feeling (reacting to whether you like or dislike the lyric) but for thinking–being objective and analytical. Using the first chapter's “Digest of Writing Theory” as a checklist, try to identify such elements as the song form, the viewpoint, the development device, the types of rhyme used. Be critical and discriminating. (Simply because a lyric's been recorded doesn't make it whole-brained.) Are there any inconsistencies in viewpoint, time frame or setting? Are there any dangling participles? It's a rare lyric that couldn't have been improved with a little more analytical thinking.

Write Small

Many Is and Js write small, carefully formed letters; it reflects the tighter nonoverlapping connections of the left-brain cells. Conversely, the handwriting of perceptives and extraverts tends to be larger and looser, reflecting the right-brain cellular connection that's more widely spaced and overlapping. Thus a concerted effort to write small, neat letters engages the concentrated and focused abilities of the left hemisphere. Remember this technique when you're feeling unfocused or “spacey.”

Preconditions for Creativity

The Mind/Body Connection

Each stage of creativity requires that the mind be in a suitably receptive mental state. To achieve that state requires that the body be in good physical shape. In addition to the value of periodic exercise, research studies have discovered our basic need to take a break in activity every 90 to 120 minutes. For optimum mental performance, we need to honor that need. So be alert to your body's signals-inattention, hunger, fatigue. A good rule of thumb: When you're nervous, meditate; when you're hungry, eat; when you're tired, nap.

The Power of Music: Go for Baroque

One of the major ways to promote relaxation and improve concentration is through baroque music-a technique now widely used in American classrooms thanks to the pioneering research of Bulgarian educator Georgi Lozanov. Research experiments have verified that 20 percent more subject matter can be covered in the same amount of time with longer retention when largo (slow) movements of baroque works are played in the background! Largo/adagio music has a tempo of about 60 beats per minute (BPMs), and because it tends to sync up with the heartbeat, produces an alpha state, the most conducive for centered thinking.

Record stores now feature baroque/adagio or baroque/largo cassettes with such popular selections as Albinoni's Adagio, Pachelbel's Canon and Bach's Air for the G String-three selections that top the baroque Top 40. To help promote a state of heightened awareness for better absorption and retention, I recommend that as you read this book you play baroque music in the background. The goal is centeredness-a readiness to alternately perceive and conceive and thus integrate the part and the whole.

Pen/Pencil and Paper or PC

Although in the upcoming exercises I may make more references to pencil and paper than to a PC keyboard, a computer will serve equally well-if not better. Keep that in mind if your MO is PC. I've found that the ability to quickly scroll, delete, block and relocate enhances my whole creative process-whether priming rhymes for a lyric, planning a seminar, or editing a book. The reduction in paper clutter alone has been a definite plus of keyboard creativity.

WrapUp

You may now feel a desire to put down the book for a bit (especially if you're an E). If so, take a break-if only to stare into space. Or, you might want to get more familiar with those four steps in the creative process-associate, incubate, separate, discriminate -and decide to reread this section with some Bach in the background. Be attuned to the message from your mind/body, and honor it. And whenever you're ready for the first strategy, turn the page.

![]()