Chapter 4

The Proper Care and Feeding of Your Facilities

Theatres are not simply buildings, but resemble complex organisms with internal systems dependent on one another to further their mission. The bricks and mortar, tools, shops, stages, costumes, props, scenery and especially the people make these institutions the places thousands flock to when they wish to escape, reflect, and dream. Theatres are also like second homes, as a place to nourish our bodies and minds, rest, and grow. Like any home, they require a great many things to keep them and their occupants operating the best they can.

The care and feeding of your theatrical home begs for careful planning. How do the different areas of our building relate to one another? How do things move in an out? What items are required to complete the necessary tasks of this space? How do you maintain and replace worn pieces? What safety precautions keep everyone happy and healthy? What is the present psychological atmosphere of the workplace? Your role as TD is to be a leader in answering these questions. That doesn’t mean having all the answers, but it does mean constantly examining these and other questions.

The job description of the TD may require taking a leadership role outside of the scene shop. This might include sound technician, PM, master electrician, and master carpenter. In most cases your responsibilities will be to oversee the scenery construction shop and possibly the machinery and condition of the stage. Often the scene shop is the largest space outside the theatre itself and has the most abundant and sophisticated tools as well as a large staff. This often makes considerations of maintenance of your domain of the utmost importance to the institution, which may also lead to your input being sought throughout the institution. This includes knowing when to seek out additional assistance from outside experts within the theatre community and from other industries.

In this chapter we will concentrate on the TD’s role as supervisor in the Scenic Construction Shop. Many of the ideas we will explore can be implemented in other areas of the theatre. All of these questions can be added to your “toolkit,” giving you a method for exploring the development of the scene shop as well as other areas of your theatre.

4.1 Shop Design

The scene shop is a critical component of any producing organization. Depending on what type of organization you work for, educational, community, regional, or commercial, will greatly affect the type or work, location, and size of this facility. As the TD, you may very well be the manager of this shop.

The scene shop is primarily, by definition, a shop where scenery is constructed. Like many things in art and life, it is so much more than what is on the surface. In most cases it is the largest nonperformance space of the artistic producing entity. It will be the site where dreams become reality. Sometimes it will be a magical place and you will be like Santa, your workshop full of cheery carpenters pulling together to make all the scenery ready for opening while they sing heavy metal songs like elves singing Christmas carols. Other times you will feel like Saruman, watching as orcs tear down trees and burn them to create seemingly horrible things that you feel forced to create by the evil Sauron. Reality will fall somewhere in between, and hopefully it will be more like Christmas than the end of Middle Earth.

In most cases you will inherit a shop. It will not be something that you have designed or had any input in its creation. If you are lucky enough to create your own or renovate an existing space, look around at as many other shops in a variety of different manufacturing disciplines as possible. You can see firsthand what works, and more likely what doesn’t. No matter what level of input you have on the space, the first question to ask is, “What does this space need to do?”

This question is the one that relates to programming. If you ever build a new facility, architects and consultants use this word to describe the process of determining who will use it and what they will be doing there. Many shops are not only for building scenery. They may need to allow for space to paint, or props may need an area for larger construction projects. Along with the physical construction, we must also concern ourselves with the planning of the construction process and general staff support. Things like offices, break rooms, personal belongings storage, even bathrooms must be considered.

Other questions get more to the heart of the construction process. What type of scenery does this organization build? Different raw materials, like wood, steel, aluminum, plastics, foam, fabric, and drapery, require different infrastructure support. Scenery construction involves so many different processes that do not appear together in almost any other industry. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set standards that advise against many of the different manufacturing processes from occurring together in the same space. Despite this fact, it is commonplace to see welding facilities and wood cutting tools in adjacent areas. As the TD, one of your major responsibilities is to mitigate the dangers caused by these different processes occurring close together.

Besides the types of products and the materials used, we must also ask ourselves what type of individual will use this facility. Will the shop see students, freelance carpenters, year round staff members, or a combination? Ultimately this question will relate directly to the purpose of your organization and be at the heart of the type of work you do and its level of complexity. If you have a largely student-based workforce in an educational setting, you may choose to have tools that are more likely to be found in shops they may encounter upon entering the workforce. You may find that with a large freelance workforce that grows from one or two to forty, you need a large number of hand tools to accommodate the changing workforce size. With a primarily full-time group, facilities like break rooms and locker rooms become an important part of making the shop not only a functional manufacturing facility, but a place where your employees feel valued since they will likely spend at least one third of their life there.

Location, Location, Location

One of the most defining characteristics that you will likely have no control over will be where your shop is located. Shop location may rank just above closets and below machinery rooms for HVAC in the hierarchy of geographic importance. The first level of this is whether the shop is on-site or offsite, meaning is the shop physically connected to the theatre or not.

In the commercial scene shop world it is unlikely that your shop would be attached to a performance venue. Commercial shops have multiple end users, and as a result send their scenery to venues all over the world. Broadway, trade shows, and touring productions tend to get their scenery from shops in this fashion. The commercial scene shop is many times a standalone entity or a component of a larger production only based company that also offers lighting and sound rental, and maybe even costumes and props. All of this scenery is built to go on trucks, sea containers, and trains, shipping to their end user.

Educational and other not-for-profit scene shops are often self-producers. For the most part the scene shop makes scenery for their productions. That’s not to say that scenery doesn’t leave and go other places, but that is usually secondary to the main goal of producing scenery for those institutions’ programs. The opportunity for an on-site shop exists with these types of organizations. You will find, however, that an on-site shop is not the rule.

Either type of shop has advantages and disadvantages. Building away from the theatre allows for more room, better tooling, no limitation on noise, and usually a less costly building. Some advantages of on-site facilities are no need to transport scenery or personnel, tools and materials are closer, scenic elements may be able to be constructed in larger pieces, and by and large you and your staff will be closer to the rest of the company.

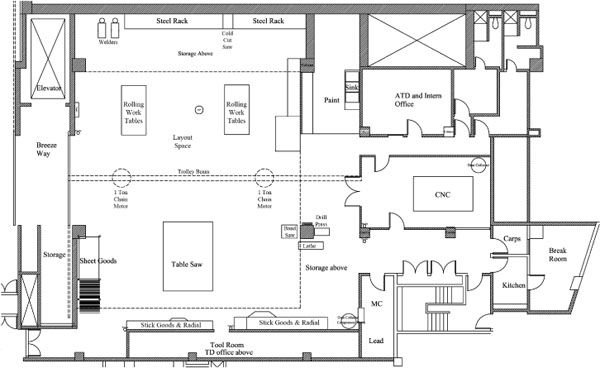

Figure 4.1 Sample Scene Shop Layout

One situation that might occur with an on-site shop is the necessity to build onstage. This challenge poses a limitation on the amount of programming and the maintenance of the theatre space. The stage is the most valuable space for any performing arts institution. While building, it is very difficult to allow any other activities to occur in the space. The opposite is true when you need to move forward with the next production, only to have to avoid being in the theatre due to a performance. Take care in planning the transition from one activity to another. Leave plenty of time for the preparation of the space for the performance.

The location of the shop is important to the mentality of a shop. Being in close proximity to the rest of the company is vitally important. We work in a collaborative art form. Being able to see and hear the work of others artists increases the effectiveness of our own work. Not to mention, sometimes face-to-face interactions will solve a vast number of issues much faster than a trail of e-mails.

Materials of the Trade

Once the shop has a location we must determine how materials get in and scenery comes out. What type of materials and how much of that material is very important? If you are going to be solely a wood construction shop, then 16 feet is probably the longest piece of material you will need to bring in. If it’s steel it could be 20 or even 24 feet depending on your vendor. You can ask for things to be cut down before delivery, but that will increase costs and create more waste.

In addition we must consider how much material we can handle and store at a time. Buying in bulk will save on the cost of material as well as delivery charges. You will most likely have to bill materials on a per project basis or per show for your institution’s accounting. If possible, having an internal inventory system for the materials you use the most can allow for large purchases and makes those common materials available when you need them. Items like plywood and stick lumber are used in almost every production in various amounts. Take care not to over buy and end up with too much material that either warps on the rack or has to be charged off to a project unused. Look at trends for previous years if possible to determine a good amount to start with.

Storage: Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Consider if you have room for the material. Do you have racks that can store material? If you have room for racks that go above what you can reach easily, do you have access to a forklift or hoist to move the material? It is important to know where to put things so they are accessible, but do not interfere with the most common tasks during construction. Keep the proximity of materials close to where they come into the shop, but more importantly near where they will be worked with. That means keeping the raw materials near the saws they will be cut with. Keep the materials supported properly as to minimize warping and out of the way of the action of your tools.

Storing tools and hardware is about keeping access easy and obvious while protecting these items from dirt, damage, and possibly theft. As we mentioned before, minimizing the number of places to find a tool or fastener will ultimately increase efficiency.

Stock scenery should be out of the way, and ideally out of the shop to help maximize the amount of space available for construction. If you must store stock scenery on-site, keep it to common sizes like 4' × 8' platforms or common step units with similar rise and run, like 8" rise with a 10" run. Make sure to keep a list of all these items and take care to maintain them. If you keep items like doors and windows, document them with pictures so you don’t need to drag them out every time you want to show a designer a stock piece.

Measure Twice, Cut Once … Then Assemble

Now that we have the raw materials in the shop, we will begin creating scenery with them. The materials must be cut and assembled into pieces and then assembled into larger scenic elements. As previously stated, ideally the raw materials will be close at hand to the tools used to mill them. Once they are cut, the next adjacent space will likely be an assembly area. One of the most challenging things to find space and time for is trial assembly. Making time and space to fit up elements as much as possible in the shop will save time at load in. It will not only speed things up, but also make a better final product.

Aside from where you assemble, you must also consider how you will be working on the materials. Tables and saw horses allow for you to work on scenery from a standing position. Anything that can be done to elevate the work will help improve the conditions for your carpenters. Building scenery is extremely physical work and by elevating it you decrease injuries and improve the quality of work. As a side note on elevated surfaces, try to keep them all the same height so they may be used in concert with each other.

Does It All Fit Together?

Trial setup also provides an opportunity to add hardware such as doorknobs and possibly mock up automation. Allowing other departments to work on elements in the shop can improve efficiency as well. Having electrics and props place practicals or install hardware for hanging curtains will lessen their work load in the theatre. This will ultimately leave less to be scheduled during the normally short load-in period. The more that you can make functional in the shop, the more confident you can be going into tech. This area is ideally as big as the playing space in your theatre and resembles the path your scenery will take to get there.

The units you have assembled in the shop may need to be broken back down into smaller pieces. The goal is not always to be making the largest piece of scenery possible to come out of a shop. The time added by assembling things in the shop, even if they must come back apart is usually worth the investment. When determining the size of pieces to ship, there are many things to consider. Perhaps the most important question is this: what is the smallest opening the scenery must pass through to get from the shop into the venue? Do not just think about how something might fit through the door, but what corridor and corners it might need to pass through, or whether it will need to be lowered down a shaft or lifted up before it goes through a door. What kind of equipment do you have or need in order to move the scenery out of the shop and into the venue? Put the scenery on wheels or carts to ease movement, but remember to take the size of the cart into consideration when determining pieces. It might be possible to build a 10,000 pound unit in one piece, but if you only have people to move it, that might not be the best option. Consider what is reasonable and safe as well as what fits.

4.2 Tools of the Trade

Determining how to move things in and out of the doors is what can make or break a shop, but how our materials are manipulated and turned into scenery are our primary tasks. The equipment our staff uses will affect the life of the shop at all times of operation. For the purposes of this discussion we will discuss types of tools, stationary or ground supported tools and hand tools.

The BIG Tools

Stationary or ground supported tools help to dictate the shop space. Allocating space for the tools and room for the material to be fed into and out of the tools creates a dance of craftspeople and material. When the layout works well, people and material can move uninhibited. Examples of these types of tools are a table saw, band saw, miter saw, metal cutting saw, drill press, and welder. These tools require space for the equipment, the material, and other accessories such as dust collection. Although a full explanation of dust collection is outside the scope of this text, it is important to consider the access to these systems when placing large tools. Also consider if these tools require other types of protective measures. If you have a metal shop with welding capabilities, you would ideally not be welding on a wooden floor or be in close proximity to wood dust.

Discussing all of the stationary tools that you might need is a text all on its own. We will highlight a few that are common to theatrical construction and a must have. In a wood shop it is common to essentially cut two types of material, sheet goods and dimensional lumber. It is possible to build entirely from sheet goods, but you still may desire tools that are traditionally used for cross cutting lumber, or cutting perpendicular to the grain.

At the heart of any shop is the table saw. This is one of the most versatile tools in your space. It also takes up the most room, so careful consideration must go into this tool’s placement. In most cases this will be a stationary tool (cabinet saw), but you can use mobile options (contractor saw) as well. A good table saw has the ability to rip, cut parallel to the grain, and crosscut a wide variety of nonmetallic materials. When purchasing a table saw, it is important to consider the power of the machine (horse power), safety measures (guards, dust collection, “Saw Stop”), power requirements, fence, maximum blade size, and runoff table needs to name a few. In some shops, you may find one is not enough. You may choose to add a second table saw or a panel saw, which orients the material vertically rather than horizontally for cutting. A panel saw is more useful as a tool to cross cut full sheets rather than ripping.

Although the table saw can rip lumber, it is not effective or safe for cross cutting to length. Imagine trying to cross cut a 16' long 1×4 on table saw! There are two stationary/ground supported tools that do this very effectively. A miter or chop saw and a radial arm saw. The first is a very flexible tool used by contractors, cabinet makers, and all types of wood construction tradespersons. The chop saw allows for cuts at multiple angles while being essentially mobile and has multiple options that can make it a very useful tool. The limitation of the miter saw is the speed of which it can cut. If you need to make a large number of perpendicular cuts, such as when processing large cut lists, a radial arm saw may be a good addition. The radial arm saw is a tool for a production shop that needs the ability to work through a lot of material quickly. It can be turned on and left on while in use, unlike the chop saw that has a momentary trigger that must be initiated for every cut. The radial can also accommodate a dado blade and can crosscut deeper material. Many radial arm saws have the ability to rotate for angles, but it is not as easily done as with the miter saw. With both options, power, dust collection, and run off needs must be considered. The ideal runoff table will allow 16 feet to one side and at least 8 feet on the other so a board can be cut in half.

None of the tools discussed thus far are very good at cutting wood in an irregular way. There are a variety of hand tools that allow this, but a band saw is the primary stationary tool for this job. The long flexible blade allows you to cut curves with ease. Unlike hand tools, by moving the material rather than the tool you may find more control over the work. The cut depth and distance from the blade to throat determine the size of material you are able to work with. Re-sawing lumber, while not as common an activity in a theatre scene shop, is a function to be considered. Cutting giant blocks of foam is also a consideration that will be limited by the size of material your band saw can handle.

Most assembly tools in wood working are hand tools, but there are some tools used for finishing and joining that are ground supported tools; stationary sanders, lathes, planers, joiners, drill press, and router tables/shaper tables are just a few of them. Many of the earlier mentioned tools will not be used all the time or may not be necessary in your shop. The stationary sander however is very useful. It can be used on a variety of material, even metal. But avoid using the same sanding station on metals and wood as fires can occur, especially in dust collectors. They take up little space and allow a great deal of control over the material as you work with the sander. The drill press is also useful in milling both wood and steel. A vertical mill or Bridgeport is a significant upgrade in functionality and machining from a standard floor supported drill press and could be appropriate for your shop.

If you have a metal shop, you will need to cut and join material together like you would with wood. In general the cutting of material can be done with stationary and hand tools, but joining material together requires more complex equipment. Cutting material can be accomplished with a tool that uses a cold process or hot process. An example of a cold process is a cold cut saw, which is like miter saw for metal. The blade moves very slowly and is irrigated with a light weight lubricant and coolant as it cuts. A metal cutting band saw works in a similar fashion. A hot process is found in saws like an abrasive chop saw, plasma torch, or oxy-acetylene cutting torch. Cold saws are slow, but produce a clean cut that requires little if any modification before welding. Hot processes create sparks and fire hazards but are much faster and capable of cutting through very heavy material. Hot processes also tend to require a great deal of cleaning up before the material can be rejoined and are often less accurate.

There are a variety of other things that can be done to metal with stationary tools. Another option for cutting and manipulating material is an ironworker. This type of machine can combine the ability to shear, bend, punch, and nip material. The ironworker essentially uses brute force to shape the metal quickly and can be moderately accurate. The punch option is a great alternative to drilling holes, although as with most fast processes the punch is not as easy to make accurate as a mill or drill press. If you need to tap a hole or size something for machinery, a drill press or mill is a better choice.

The ironworker can bend steel into angles, but for ornamental bending and circles Hosfeld manual benders and roller benders are worth exploring. Using a Hosfeld is a skill all in its own, but some truly beautiful things can be made with this tool. Roller benders come in manual and electric versions. If you have ever made a circle by kerfing steel, you will relish in the joy of having a circle bent with a roller bender.

Before welding you may need to prepare the steel with some grinding. Many of us have used stationary grinders for this purpose. We encourage you to look for alternatives, as these tools are essentially for maintaining chisels and if the tool rest is not adjusted properly, they can cause serious injury. As mentioned previously, a stationary sander may be the option.

Now that all the material is cut, bent, shaped, and has its holes punched or drilled it’s time to put it back together. You will use a fastener, bond the material with adhesive, weld the material together, or use some combination. We discussed punch or drilling above for tapping and bolting applications, so let’s talk about welders. Welding creates many hazards. Consideration for the proximity of this activity to flammables and other unprotected personnel is of the utmost importance. You can divide welding into arc and fuel gas welding. Fuel gas welding, such as oxy-acetylene, is rare with its slow speed and the hazards of having highly flammable gases indoors. You may find it to be a very useful educational tool as the speed of welding with gas is slower and allows a more suitable process for teaching. Arc welding is more common and more efficient in most cases. Stick, MIG, and TIG are the common types of arc welding. The most common, and arguably the most easy to use is MIG welding. MIG welding uses a consumable wire that fills the void created in the parent material as the welding occurs. MIG can be used for steel and aluminum (with modification). Although TIG is the choice of most for aluminum, if you do not weld aluminum on a normal basis or need it for an educational purpose, it may not be a tool you choose to invest in.

Although not a tool, be aware of the need to clean metal before working it. Steel often comes with a light oil or pickling which prevents rust. Finding a place to do this with a nonflammable solution like Simple Green is a challenge and can be time consuming. It also makes a mess.

The Power Is in Your Hands

The volume of dizzying information and types of hand tools is overwhelming to say the least. We will not discuss all the myriad tools needed to run a shop, but try to discuss some big decisions that will inform those tool chooses. First off, hand tools can be powered by people or by some other force. Before the advent of steam, most tools were human or animal powered, but today it is almost impossible to consider doing our work without them.

There are two schools of thought we might use when choosing hand tools. Are they disposable or not? This question comes from two additional questions: who will be using them, and what is their purpose? This ultimately informs the choice of the quality and disposability of the tool. Now right here you might be thinking, always use the best tool for the job. Spend extra money if needed to get the best tool. With large power tools, this is certainly true, but with hand tools it’s not so simple. If you have a project that requires a messy process that could destroy a tool, like carving foam, maybe you buy cheap steak knives from the dollar store rather than fine chef’s knives. In addition if you have mostly students in your shop who change semester to semester or temporary carpenters as a workforce, you may find that tools walk off or get damaged by misuse. Buying $20 screw drivers may not be an option if you need to replace them every 3 months. A favorite example of mine are chisels. Chisels are not screw drivers or paint can openers, except when they are misused that way and the blade edge is broke off. As a result you may choose to spend less on this item.

Hand power tools are a lot more like stationary tools. They don’t walk off as easily and tend to be more of investment. The obvious questions about what types of materials you will be working on and the processes needed to manipulate them exist, but some new questions arise. How many craftspeople need to use these tools? How much does the size of your crew change from day to day? Also consider what happens when a load in starts and you need to continue construction in the shop. Having enough tools to move a large number out of the shop is difficult to achieve and maintain, but without it productivity in the shop can come to a screaming halt.

A big decision about power tools comes in the choice between electric and pneumatic. Both have some great advantages. Determining the type of fasteners is one major factor. It isn’t one way or another; you certainly should have both options available in your shop. The speed and low cost of pneumatic fasteners makes them a great choice in the shop, but the tether of a hose to an air compressor makes them less useful outside of the shop space. Electric power tools can be battery or AC powered. AC gives more power. Battery-powered tools give the most flexibility, but have the challenge of less power, the need for recharges, and some added weight. As technology has improved the battery powered tools have closed the gap on their AC counter parts and even created some tools that mimic pneumatic fasteners. In the realm of cordless drills this is especially true, although we are still firm believers that if you need to drill holes in steel and can’t use a drill press, please use an AC drill. Remember that these tools require additional support systems in your shop, like an air compressor, or multiple electrical outlets to run the tools or even to charge your batteries.

Processes besides wood and metal working may also occur in the scene shop. Softgoods, fabric construction, foam sculpting, rigging and painting are just some to consider. Softgoods require a clean area where fabric can be cut and sewn as well as having grommets attached. Good scissors that are only used for fabric and an industrial sewing machine are not just tools for a costume shop. They are vital tools and the skills to use them should not be underestimated.

With foam and painting, there are many procedures that use sprayers. This requires ventilation and some need access to compressed air. One tool a TD uses that is extremely valuable but needs careful planning to use is the airless sprayer. This is a pump that pushes paint without an exterior hookup to an air compressor, and it is an amazing tool for back painting. A trained individual with plenty of paint and easy access to the scenery can back paint a set in a day. Also think about spray booths for the use of materials like spray paint. If you can’t find an alternative to a toxic chemical don’t only think about protecting the user, but also those passively being exposed to the chemical.

Now that you have all these tools you must figure out how to power and store them. All tool power should run through an emergency shut off that cuts power to all outlets and tools. Actuators for this should exist in multiple locations. Your building’s electrician should be able to help you with determining how to make it happen. Stationary tools are a little more straightforward, but considerations for power hand tools takes some planning. Having access to air and power at multiple locations improves productivity. Hose and power reels mounted to the ceiling help keep cords out of the way.

Sorting the tools and hardware is seemingly a never ending struggle. How to organize and store enough to maintain a productive shop without making it impossible to find what you need is a favorite topic of debate in any shop. There are as many opinions on how to organize tools and hardware as there are TDs. Try to keep the number of locations for like items to a minimum. Stocking screws in four areas in the shop may make it easier to get to them, but tends to create confusion when looking for items. Minimize the number of fastener sizes to the necessary lengths. Do you need every narrow crown stapler size in 1/8" increments? Probably not. Less is more. Use like tools. Yes Brand A might make a better cordless drill, and Brand B makes a better cordless circular saw, but they use different batteries. Struggling to find the right battery is not what you want to be doing during a tech rehearsal that is being held while you go to fix a problem.

Although not directly concerning the scene shop, consider how you need to move tools and hardware to other spaces. Will you need to take tools away from those used in the shop? Are there some tools that you wish to have as dedicated load-in or strike tools and hardware? These questions will have a lot to do with where you are moving scenery to and from. It is not likely that you can create a fully stocked mobile shop, but hitting the most common tools and fasteners will save trips to and from the scenic studio.

There is much more that could be said on the subject of shop design. This chapter just scratches the surface and aims to get you thinking about the problem from all angles. Look at as many other shops as possible and maintain flexibility in your space design. Things change and so may the needs of your space. To further understand this complex component of Technical Direction see the companion website to this book for a detailed list of many of the items we have discussed and other items to include in your shop.

4.3 Maintenance and Repair

Maintenance and repair of equipment and your building is an ongoing and tragically sometimes ignored process. The rigors of constructing scenery can leave little time for the upkeep of your shop and spaces. Being aware of these challenges requires that you plan time to complete these tasks.

When evaluating how to keep your work environment in good repair, it is important to concentrate on the maintenance so that you minimize the repair required. Maintenance should be done on a consistent basis at scheduled times. Try to search for obvious breaks in your schedule to allow for maintenance to occur. It is also a good idea to spread out your maintenance. It is unlikely that you can complete all of it in one fell swoop. Different equipment also requires different periods of time between maintenance. When reviewing the maintenance schedule outlined in the tool manuals, take into consideration how much you use that equipment. For example, a tool may require greasing every 6 months, but that is based on heavy use. If you rarely use a tool, maybe it can wait until a year goes by. The inverse is of course true, if you use the tool more heavily than the normal maintenance cycle suggests.

If possible, it helps to spread out the maintenance work to your staff. One strategy is to create areas in the shop or onstage that are the responsibility of certain staff members. Each carpenter works on a certain area during cleanup and takes time to keep up with the necessary procedures to keep things running smoothly. Another option is to set aside weekly times solely devoted to maintenance, outside of normal shop cleanup time.

Remember that some maintenance requires a trained professional. Don’t hesitate to have a specialist work on your valuable equipment when the level of care is beyond your capabilities. Sometimes it’s worth investing in additional training to be able to service specialty items, like chain motors. Even if you do get training in maintaining something, having someone else to call in an emergency is a good idea. No matter how well you maintain your equipment something may fail, and usually at the most inopportune time. Calling someone who is not trying to build scenery can save the day and is worth the expense.

Keep track with a maintenance log of tools and systems so you know when the last maintenance occurred. The date of purchase and any repairs should be listed as well as description of the repairs completed. This log can also act as an inspection log for systems like rigging and automation systems that are complex and have multiple components that each requires maintenance.

Beyond the obvious lubrication and tightening of fasteners remember the consumable items that your tools use. Keep saw blades and drill bits sharp. Replace sanding disks and belts, filters, and screens. There is also the need to keep the runoff tables and fences true. Paying continual attention to the condition of guides, guards, and tables associated with tools will make them function better, last longer, and produce a better product.

Maintenance dictated by the manufacturer is a great start, but not everything has a manual. Floors, doors, and windows need repair and maintenance as well. The stage and shop floor are one of the hardest working pieces of your building. Shop built carts and dollies are abused and need attention, hopefully before they break. Stock scenery and soft goods also require attention. Retreating flame retardant on your stock curtains is not only necessary, it’s the law.

Maintaining and repairing equipment has another component, and that is replacement. Sometimes it’s better to get a new item then try to fix it. Upgrades to technology or the prohibitive cost of working on older equipment may make buying new a better option. Also remember that some tools are more disposable and your time is more valuable somewhere else, rather than fixing that $70 narrow crown stapler.

The best defense against being surprised by huge replacement costs is planning for rotation of equipment. This requires investment from your institution, so it is incumbent on you to be an advocate for this kind of forward thinking. Beyond it being necessary, buying new tools is fun. It’s one of the best parts of the job.

Maintenance and repair can be a tedious part of the job, but it is one of the most necessary. However you approach it, make sure you look to the future and try to anticipate problems before they become catastrophes. Good TDs don’t like surprises and excel at seeing into the future. This is just another part of that skill set.

4.4 Morale Maintenance

The truth is sometimes, especially in theatre, we spend more time with those we work with than our families. As a result interpersonal relationships are a critical part of the shop’s function or dysfunction. Depending on the environment your staff and coworkers could be students, theatrical professionals, other tradespeople, or even volunteers. Despite these differences there are some universal ways in which we can maintain a positive work environment. There are literally thousands of pages about this subject. It may be overly simplified, but we like to think that respect is the foundation for a positive workplace.

Respect has many facets and can filter down into every part of how we interact. There are the base level elements of respect that are about allowing each of us to be the person we were born to be and choose to be. Many of these elements are protected by law, and as a supervisor or educator you must be aware of them. Not only because it is the right thing to do, but because you have a legal obligation to do so. Liability is a part of our job and we must take it seriously. Going into the specifics is beyond this discussion, but we encourage you to work closely with your Human Resource professionals to be compliant and proactive about this subject.

Respect for your colleagues work is another element of a positive work place. Respecting others work means empowering them to do their job. We see the job of a supervisor as one who empowers their workforce through communication and planning.

Communicating effectively requires a certain level of trust and bi-directional listening. Information cannot just go one way. If the supervisor is always giving directives without getting assessments from those doing the work or considering the suggestions they make, you will soon be in the dark about what is going on. We have learned to trust the “people on the ground.” Sometimes being up front and directly involved with the project gives you an insight that the TD cannot get as readily. By combining your overview with the details from your carpenters you can make the most informed choices. Listening is also the key ingredient to the design process. In order to problem solve an over-budget design, understanding the creative teams approach and working together is the only way to be successful.

Another part of communication requires the honest assessment of skills and products. The scene shop is a manufacturing shop. There is a product. Not every technical direction task or project has scenery involved. There are also services that are provided, running shows, planning load in, construction drawings, customer service, etc. In a school environment, where your goal is teaching students skills in technical production, assessment must be the foundation of your work. Teaching and testing skills is a constant part of the process. It may be harder to assess and give feedback in other environments, but that should not discourage you from trying. If something good happens, let your staff know. Pass along praise, and do not forget to say thank you.

What is harder is knowing when and how to bring up problems with someone’s work. A review or a pink slip should not be when a staff member finds out there is a problem. Neither should it be in a public manner on a daily basis. Show the individual respect by discussing the concerns you have in a private manner. If it can be done on neutral ground (not your office) it may be received better. Documentation of the issues and the conversations about them should occur when simple discussions do not work. Not only does this send a message and create a plan of action to correct these challenges, but it shows you proceeded with respect and clarity about the performance of the individual. When performance issues escalate, bring your supervisor and HR department into the discussion. Having a third party involved is a protection for both you and those that work under you.

Planning and doing your homework shows respect as well. Having the necessary information correctly and efficiently put together will make your staff’s job easier. You are busy and go to tons of meetings. Your boss needs you to meet certain deadlines and your job depends on it. Although you cannot forsake this, not completing the tasks needed for your carpenters to build scenery, letting materials run out, or leaving tools unrepaired will cause your team to break down and the trust between you and your staff will be damaged. Remember that those individuals in your shop can be your closest allies. When they do well and succeed, so do you, and vice versa.

The last part to touch on is the respect for people’s psychological well-being. This can mean a lot of things. Sometimes it’s making sure people can take the time off they are entitled to or being responsive to challenges outside of the workplace that cause them to miss work or be distracted. It can also mean celebrating at work and taking time to show you care about your staff as people. Pay attention to the mood in a shop. If morale is down it can do more damage than any other catastrophe.

The power of the baked good should not be ignored. Doughnuts, cupcakes, shop lunches, and break time popsicles can make a difficult time a little more bearable. It gives us a chance to step away from the grind, have a treat, and socialize. It’s even better when other shops can participate. The more the merrier. Celebrating birthdays, births, marriages, any milestone that seems appropriate and for which the person being celebrated does not mind the attention is a great boost to shop morale.

Traditions are important ways to bring a sense of team and mutual respect to an institution. Creating and celebrating these traditions can be a positive reminder of the work we have done together. Stagehands love telling stories, and if a tradition can come from a unique story in the shop, all the better. One of my favorite traditions is a celebration we called Meatfest. Multiple times a year, the people of Florida State University School of Theatre would gather to eat meat and tell stories about what we had seen and done. It was simple and ultimately just about people getting together. That tradition became a bit of a legend and has made its way across the country with each of us that participated in those events in school. Now there are Meatfest celebrations at theatres all over.

Maintaining positive morale in your institution takes great care. It is more important to me than any tool, building, or technique. Performing arts are about people. They are the greatest asset of any shop or institution. Without them, what’s the point? Take care of one another. You won’t regret it.

4.5 Health and Safety

Safety Culture

The question of health and safety brings forth high emotions in many of us. One might feel under protected and fearful of the conditions in which they are asked to work and live, or overly burdened by restrictive work rules that inhibit efficiency and ease, or some combination of both depending on the situation and timing. All of these conditions have a source, and it is often a lack of knowledge and ownership. The single greatest tool for improving these attitudes is by developing a safety culture.

Our friends at the Department of Labor define safety culture as “consisting of shared beliefs, practices, and attitudes that exist at an establishment. Culture is the atmosphere created by those beliefs, attitudes, etc., which shape our behavior.”1 It is very easy to spend huge amounts of time and energy creating policies which are based on law and reason which fall short because the members of the team do not buy in to the underlying values represented in your practices.

There are many facets to developing this idea. Each one is less effective on its own. Policies and procedures do little without accountability and training. Knowledge of safe and unhealthy practices is easily diminished by myths or partial knowledge. Finally the thing that seems to make it all fall apart is a lack of employee ownership in the process.

As the TD you will often be asked to be a leader in the developing safe and healthy practices in the workplace. While being a manager gives you authority, consideration of the concerns and views of your team will be the key to success. One option to instill ownership and give a voice to everyone is the establishment of a Health and Safety Committee. A Health and Safety Committee is often an advisory unit, not a policy setting one, but it does provide the opportunity to establish a dialogue within the workplace and a medium for discussing issues. The part of upper management and administration cannot be diminished in this equation. The TD can be placed between the safety of those producing and those administering in a potentially difficult and hazardous way. Facilitating the flow of information up and down the chain of command is vital to ensuring the best working conditions possible for everyone.

OSHA

There are many resources for research and development of safe and healthy work practices. Many are free or little to no cost. OSHA, or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, is one of the greatest resources for this, and it’s the law. The OSH Act was made law in 1970 and outlines an employer’s responsibility to provide for a safe workplace and puts in place means for the protection of employees who report violations.

While OSHA is educational and must be followed as law, its effectiveness is compromised by the complexity of the act and the challenges of enforcement. There are two sections of the Act that most often relate to our work, Part 1910 and Part 1926. The entertainment industry in this country has very little regulation specifically about our work. These two sections outline general industry and general construction workplaces.

NFPA 101

NFPA 101 is the set of codes and standards from the National Fire Protection Agency known as the Life Safety Code. While OSHA deals directly with the Hazards and Conditions in the workplace the Life Safety Code as described by the Association itself is “the source for strategies to protect people based on building construction, protection, and occupancy features that minimize the effects of fire and related hazards.”2 The usefulness of this document for the TD continually shows when dealing with the interaction between audience and the stage. Questions of egress and occupancy are often discussions when dealing with flexible spaces and shop built audience seating systems. How big can a step be? How wide is the aisle? Do these seats need to be fastened to the floor? Is there enough house lighting available for the audience to see? While some of these questions seem far outside the realm of the TD’s responsibility, we will often be tossed square into the middle of these things and having a resource to guide the discussion is ideal.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Another law that often coincides with NFPA 101 is the Americans with Disabilities Act. Like OSHA, ADA is administered by the Department of Labor and is the law of the land. Not only is this an important component of general legality in the workplace, but when discussing seating arrangements and accommodations for disabled patrons, this will guide you.

Entertainment Services and Technology Association (ESTA)/PLASA

Although there are few laws directly related to the entertainment industry there is an independent organization known as the Entertainment Services and Technology Association that has merged with the Professional Lighting and Sound Association, PLASA which has published standards through ANSI. This organization brings leading professionals in the entertainment industry together to determine best practices in areas such as rigging, atmospheric effects, and control protocols for technology such as lighting control. Where there is a gap in regulation, many industry specific practices may be represented by PLASA standards.

Training

Training may seem obvious, but it is also a large portion of the laws which govern workplace health and safety. Preventing injuries and long-term health issues can be mitigated in a number of ways. We must understand what we are using and how to use it. Practical, documented, consistent training is vital to your safety culture.

The place to start is with knowledge about the materials we use. For instance, OSHA requires training in the use of the Global Harmonizing System of Classification and Labeling Chemicals. This system has replaced Material Safety Data Sheets with a more universal and easily readable version for every material and chemical produced for us in the United States. Understanding the physical processes used is also extremely important. How to use tools properly, climb a ladder, lift a heavy object for instance will instruct our interaction with the physical processes of producing for the theatre.

Once we establish the understanding of What? and How? we should ultimately then ask Should we? Understanding the risks allows us to then evaluate if there is a less dangerous option. Maybe there is another product or different saw that would make the job safer.

Developing a documented training regimen can be challenging, but with the help of those invested around you the load can be lightened. Ideally you would be able to create an annual program which addresses the many hazards we face in the work place. Looking to OSHA, the manuals for your tools, texts such as the Health and Safety Guide for Film, TV, and Theatre by Monona Rossel, and independent consultants or training companies can help guide you along the way and fill in the gaps in your knowledge. There are independent training organizations to train in the use of items such as fall arrest and proper respirator fit testing and medical examination. You can also seek a certification in entertainment-based specialties such as theatrical and arena rigging or entertainment electrician through the Entertainment Technician Certification Program (ETCP). Remember that you don’t need to know everything; you just have to know where to find the answers.

PPE

Personal protective equipment or PPE is often thought of as the first line of defense, but we often think of it as the last. We have cultivated a concern for our own and each other’s health and safety first, then researched our compliance with the law and best industry practices, then trained ourselves on the hazards we may find, and worked toward finding less dangerous alternatives. After doing all this for whatever hazards we have left, we must still try to mitigate there effect on us. PPE is our shield.

Using protective equipment should be like putting on clothes in the morning, and cloths are technically PPE if you think about it. It all goes back to that community of best safety practices. We cannot eliminate all hazards or risk. So evaluating the risks and properly insulating ourselves against them is essential. One of the most difficult things about getting people to use PPE is defining when the right time to use it is. Fortunately the law states our responsibility to understand, use, be provided, and trained on its use.3 Within our own institutions we must be vigilant in holding each other accountable for best practices and use of PPE. Be consistent and act as a model for its implementation. Be careful in allowing too complex of a policy where there are a number of exceptions to policies. This will only weaken your program and create confusion and lack of trust.

Continuing the Conversation …

Creating a healthy and safe work place is an ongoing process. Do not get discouraged by the massive amount of dangers you may be faced with mitigating. Do your best to use the resources available to increase your compliance with the law and nurture a safe and healthy workplace. Remember that your greatest tools are those that work next to you. Do not forget the common sense items like taking breaks, working with a buddy, staying focused, and communicating with one another.

As we have said on multiple occasions in this text, do not feel as though you must have all the answers. Look to experts, request additional professional training, and speak up. The TD wields great power and ultimately great responsibility. Being responsible also means recognizing when and seeking out help.