A Simple Framework

for Leading Innovation:

The Three Boxes

Leaders already know that innovation calls for a different set of skills, metrics, methods, mind-sets, and leadership approaches: they understand that creating a new business and optimizing an already existing one are two fundamentally different management challenges. The real problem for leaders is doing both, simultaneously. How do you align your organization on the critical, but competing, behaviors and activities required to simultaneously meet the performance requirements of the current business—one that is still thriving—while dramatically reinventing it?

Managers and executives, consultants and academics, and analysts and thought leaders around the world have long wrestled with this question, and in response, some of them have developed a concept known as “ambidexterity”: an organizational capability of fulfilling both managerial imperatives at once.1

But what’s missing is a simple and practical way for managers to allocate their—and their organization’s—time and attention and resources on a day-to-day basis across the competing demands of managing today’s requirements and tomorrow’s possibilities. Managers need a simple tool—a new vocabulary, if you will—for managing and measuring the different sets of skills and behaviors across all levels of the organization. They need a practical tool that explicitly recognizes—and resolves—the inherent tensions of asking people to innovate and, at the same time, to run a business.

What’s more—as anyone who has tried to lead innovation knows—the challenge goes beyond being ambidextrous in order to simultaneously manage today’s business while creating tomorrow’s. There is a third, and even more intractable, problem: letting go of yesterday’s values and beliefs that keep the company stuck in the past.

What leaders need now is the Three-Box Solution.

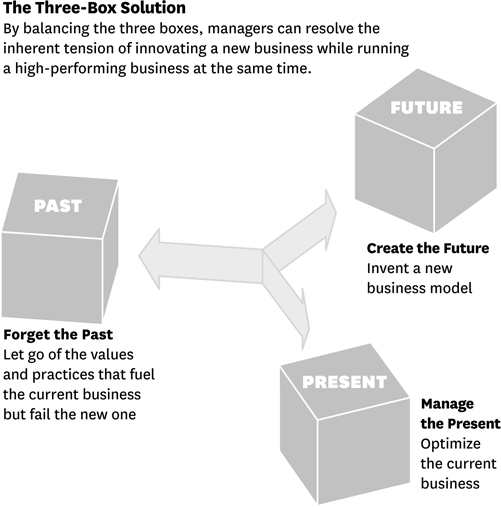

The Three-Box Solution

The ability to achieve significant nonlinear change starts with the realization that time is a continuum. The future is not located on some far-off horizon, and you cannot postpone the work of building it until tomorrow. To get to the future, you must build it day by day. That means being able to selectively set aside certain beliefs, assumptions, and practices created in and by the past that would otherwise become a rock wall between your business of today and its future potential. This basic idea is behind what I call the Three-Box Solution (see figure 1-1).

The Three-Box Solution is a simple framework that recognizes all three competing challenges managers face when leading innovation. It’s a powerful guide for aligning organizations and teams on the critical but competing activities required to simultaneously create a new business while optimizing the current one. In the three boxes, companies must do the following:

- Box 1—Manage the present core business at peak efficiency and profitability.

- Box 2—Escape the traps of the past by identifying and divesting businesses and abandoning practices, ideas, and attitudes that have lost relevance in a changed environment.

- Box 3—Generate breakthrough ideas and convert them into new products and businesses.

Success in each box requires a different set of skills, attitudes, practices, and leadership (see table 1-1).

TABLE 1-1

The Three-Box Solution

| Strategy | Challenge | Leader behavior | |

| Box 1 | Run core business at peak efficiency; use linear innovations within existing business model to extend brands and/or improve product offerings. | Keep focus on near-term customer needs; optimize operations for high efficiency/lowest reasonable cost; reduce variance from plan; align rewards and incentives with strategy. | Set challenging goals for peak performance; analyze data to quickly spot and address exceptions and inefficiencies; create a culture of doing everything smarter, faster, cheaper. |

| Leaders at all levels, especially CEOs, must pay regular attention to each box. | |||

| Box 2 | Ability to build the future day by day begins here; create space and supporting structure for new nonlinear ideas; let go of past practices, habits, activities, and attitudes. | The past always fights back, so be prepared to make tough calls about values Box 3 needs to leave behind (remembering that some are still useful and needed in Box 1). | Establish formal regime of planned opportunism (i.e., gathering and analyzing weak signals); champion the ideas of maverick thinkers; do not tolerate obstructionism—set an example for the enterprise by visibly and publicly penalizing foot-draggers; anticipate the need for an orderly process of experimentation. |

| Just as Boxes 2 and 3 must be protected, Box 1 must remain focused and undistracted. | |||

| Box 3 | The nonlinear future is built mainly by experimentation that tests assumptions and resolves uncertainties, hedging risk; new learning either strengthens an idea or reveals its weaknesses. | It’s not always obvious which ideas to pursue first—you need a method to gauge relative value and priority; expand variance, knowing success rate in Box 3 experiments is low; do not trim sails on Box 3 projects in a downturn. | Measure progress of Box 3 efforts not on revenue development but on the quality and pace of learning from experiments; since many nonlinear ideas launch into embryonic markets, it’s important to test assumptions not only about the product but also the business model and the developing market. |

| With the three boxes kept in balance, a business can change dynamically over time. | |||

By balancing the activities and behaviors associated with each box, every day, your organization will be inventing the future as a steady process over time rather than as a onetime, cataclysmic, do-or-die event. Simply put, the future is shaped by what you do, and don’t do, today.

What You Will Get from This Book

I have developed the Three-Box Solution over the course of thirty-five years of working with and doing research in corporations worldwide. It is the foundation of my thinking and teaching about strategy and innovation. In presenting the three-box framework to students and executives, I have been gratified to see how strongly it resonates with people. Business leaders from all kinds of organizations, such as GE, Tata Consultancy Services, Keurig Coffee, IBM, and Mahindra & Mahindra, who are featured in this book have told me they value the simplicity and clarity of the framework. But even more, they recognize that these ideas have the power to solve complex and intransigent business problems. As Beth Comstock, who serves as the president and CEO of GE Business Innovations and GE’s chief marketing officer (CMO), told me:

The three-box framework allowed General Electric to develop processes around our “protected class” of ideas that are given more time and space to prove their worth after they pass through an initial stage of rigorous testing. This “pivot-or-persevere” mind-set has allowed us to function more as a start-up and given rise to products such as the Durathon battery, which we took from lab to market in five years. Along with helping to set and align our portfolio, the three-box framework led us to think of innovation as a process. It’s the way we’re evolving the company and becoming faster, simpler, and more inventive.

Her colleague, Raghu Krishnamoorthy, the vice president of human resources at GE Crotonville, echoes these themes, emphasizing the lasting impact of the ideas on the company:

The three-box framework gave our business teams the opportunity to reflect, debate, and establish the strategic center of gravity in both short and long terms. And it sparked new conversations within the organization relative to where energy and resources should be spent to achieve the best balance in managing “the current” while creating “the future.” The approach proved to be effective across the company as leaders recognized a more powerful correlation between quantum improvements and quantum change and made a lasting impact in expanding our views, strengthening our culture, and positioning our organization for continued growth.

My aim in writing the book is to provide insight and guidance that will help you and your organization attend to the long-term future with the same commitment and consistency with which you are driven to act on the clamorous priorities of the present. My hope is that the Three-Box Solution will make your job of leading innovation easier, with a simple vocabulary and set of tools that you can cascade down and across your organization, as GE has done.

The Three-Box Solution describes and illustrates, with in-depth examples, the framework for building the future continuously instead of waiting for the next crisis or for a new competitor to come out of the blue with a brilliant future you never imagined. The book is meant for leaders at all levels—from the small team to the functional department, from the business unit to the corner office, from managers responsible for the daily execution of the core business to those who drive and inspire innovation. The more people in a company who understand how the three boxes work, the better prepared that organization will be to anticipate and exploit changes of all kinds—to act instead of react. The Three-Box Solution framework has the potential to transform the future of any organization that embraces it, whether it’s a large, for-profit enterprise; a midsize business; or a small nonprofit institution.

Let’s turn to the story of one of those organizations.

Transforming Hasbro

In the mid-1990s, toy giant Hasbro saw itself as a product company. Its offerings consisted mainly of toys (among them G.I. Joe, Transformers, and My Little Pony) and board games (The Game of Life, Monopoly, Candy Land, and Chutes and Ladders). Hasbro competed in an industry broadly referred to as “family entertainment”—toys and games described by marketers as appealing to “kids from two to ninety-two.” Until the 1990s, people typically purchased Hasbro products in a retail store. Customers shopped, bought, and returned home with a toy or game.

Today, Hasbro is very different; it’s a self-styled “branded-play company.” Its relationships with customers may or may not begin with a physical product on a physical shelf. Instead, the Hasbro universe features numerous constellations serving as points of entry. Customers get to know and use Hasbro’s core brands across multiple platforms: online games and fan sites, movies and television shows, digital gaming systems, and comic books and magazines produced through partnerships with Disney and other companies. The goal is to create many opportunities for ongoing exposure to, and experience of, the various Hasbro brands. Hasbro has parlayed the popular Transformers line, for example, into a wide array of media, products, and experiences. (See the sidebar, “Transformers’ Metamorphosis into a Lifestyle Brand.”)

Transformers’ Metamorphosis into a

Lifestyle Brand

Hasbro’s line of Transformers toys and action figures is aptly named. Since the creatively changeable products debuted in 1984, they’ve morphed into an ever-expanding array of branded manifestations beyond the toys themselves:

- Universal Studios Hollywood, Transformers: The Ride-3D (you must be at least forty inches tall)

- Movies and television shows

- Clothing (T-shirts, jackets, hoodies) in infant, child, and adult sizes

- Character costumes, including helmets, masks, armor, and weaponry

- Backpacks and lunch bags

- Games for Xbox and PlayStation console systems

- Room décor, including Transformers-themed comforters, sheets, pillowcases, and wall decals (be sure to get Mom’s permission first)

- Print and digital comic books (through an arrangement with IDW Publishing)

Many of Hasbro’s other brands have also pursued this kind of ubiquitous experiential marketing strategy—lifestyle brands that have a 360-degree impact and influence on consumers. While families might once have played board games together on rainy days or in the evening, today they can wear branded Transformers clothing, go to Transformers movies, travel to theme parks to experience a 3D Transformers ride, or decorate their children’s rooms with Transformers bedding. The Box 3 strategy is to create and capture value from the brand across multiple platforms.

Source: Photos copyright TRANSFORMERS® and copyright 2015 Hasbro, Inc. Used with permission.

For Hasbro, the differences between the past and now are dramatic. Yet, over the years during which I have closely observed this company, I have been struck by the fact that the changes were not sudden but were the result of continuing attention, experimentation, and learning—some of it ambiguous or inconclusive—that spanned most of two decades. For Hasbro, inventing the future was more of a steady process than a cataclysmic event.

The story of Hasbro’s transformation neatly showcases the themes at the heart of this book: how organizations can, in a balanced way, manage their present core businesses at peak efficiency and profitability (Box 1); escape the insidious traps of the past (Box 2); and innovate nonlinear futures (Box 3).

Why Is It So Hard to Balance the Three Boxes?

For a long time, I have been troubled to see how often organizations fail to invest wisely in their futures while instead placing dominant emphasis on the present. To be sure, the Box 1 present is vitally important. Box 1 is the performance engine. It both funds day-to-day operations and generates profits for the future. Where problems arise is when the present crowds out other strategic priorities—for example, when the only skills brought into a business are those that serve today’s core.

That is shortsighted in every sense of the word. As Box 1 grows in dominance, Box 3 languishes and Box 2 barely exists. This is a tragic waste. Businesses achieve strategic fitness only when they thoroughly understand and carefully manage the benefits and risks of each of the three boxes. The three-box framework will help you deliver stronger overall performance and more-innovative futures while also building an organization fit to survive not just from quarter to quarter but for generations. As Karim Tabbouche, the chief strategy officer of VIVA Bahrain, told me: “Our planning process had become myopic and short term in nature, with our objectives becoming tactical and linear in nature. The three-box framework has challenged us to redesign the planning process, which would allow us to brainstorm Box 2 and Box 3 nonlinear initiatives in addition to undertaking Box 1 operational excellence initiatives. It is important to allocate resources to Box 1, Box 2, and Box 3 projects to maintain a healthy balance among the boxes.”

Yet it is not surprising that so many organizations focus mainly—even exclusively—on Box 1. The Box 1 present is their comfort zone, based on activities and ideas that are proven, well understood, and firmly embedded in the business. Most firms’ organizational structures were built on the successes of the past, refined over time to support the priorities of the present core business, and focused on maximizing cash flow and profit generated by the core.

By comparison, the Box 2 work of avoiding the traps of the past is difficult and painful. It may require wrenching management decisions to divest long-standing lines of business or to abandon entrenched practices and attitudes that are unwelcoming or even hostile to ideas that don’t conform to the dominant model of past success. Moreover, the Box 3 methodology for creating the future consists of leaps of faith and experimentation that are fraught with uncertainty and risk. The regime calls for entirely different management strategies and metrics than does the relatively settled and predictable work of executing the present core business at the highest level.

So Box 1 is, by contrast, a tranquil refuge:

- The rewards of focusing on the present are immediate, easy to forecast, and easy to measure. Markets apply continuous pressure on businesses to maximize present opportunities and opposing pressure to steer clear of nebulous long-term distractions.

- The skills and expertise needed to thrive in the present are known and abundantly available, whereas ten to fifteen years out is a black box. Every bet you place on the future is an exercise in brain-cramping guesswork. And the results likely won’t be known for a long time to come.

- The risks of the present are relatively low. Those that exist—market volatility, macroeconomic forces, competitors’ moves, and regulatory and political changes—are generally well understood and manageable through established means.

- Even though the long-term risks of neglecting the future are immense, they are too distant and abstract to provoke a sense of motivating urgency.

Yet a sense of urgency is exactly what’s needed. To become disproportionately devoted to Box 1 is to leave vital organizational muscles underdeveloped; when you suddenly need them in a pinch, they won’t be ready. The only sane recourse is to exercise all of the organization’s muscle groups regularly, just as you would to keep yourself physically fit. The three boxes, managed together and given the requisite ongoing attention, achieve a level of balance that in the long run helps organizations avoid self-inflicted crises and respond opportunistically to the unavoidable ones.

One of the things you will discover, once you begin to pay daily attention to each of the three boxes, is that they are interrelated and indispensable to each other. I like the way Hasbro CEO Brian Goldner describes them: “For me, the three boxes are like a Russian nesting doll. They are doppelgangers that are influenced by the shape and size of the others and can’t be dealt with separately.”

Another thing you will discover is that although they are interrelated, the three boxes call for divergent skills, disciplines, and management strategies. Leaders therefore need to become more than ambidextrous, as I mentioned earlier, as they transition among the boxes. Because it is so easy to default to Box 1, spreading attention around to all three will require conscious discipline. Hasbro’s Goldner logs the amount of time he devotes to each box: “I quite literally review my calendar every week to make sure I’m allocating enough attention to Boxes 2 and 3.”

The goal of achieving balance among the three boxes requires understanding that each box defines success in its particular context:

- The skills and experience you apply in Box 1 allow you to operate at peak efficiency and execute linear innovations in your core businesses.

- The skills of Box 2 allow you to selectively forget the past by identifying and divesting businesses and abandoning practices, ideas, and attitudes that have lost relevance in a changed environment and would otherwise interfere with your focus on inventing the future.

- The skills of Box 3 allow you to generate nonlinear ideas and convert them, through experimentation, into new products and business models.

Ultimately, the Three-Box Solution is about managing the natural tension among the values of preservation, destruction, and creation—forces with which I was abundantly familiar growing up in India. (See the sidebar, “The Hindu Roots of the Three-Box Solution,” for a glimpse into my framework’s philosophical underpinnings.)

The Success Trap

The biggest challenge you have in balancing the three boxes is that the greater your success in Box 1, the more difficulties you are likely to face in conceiving and executing breakthrough Box 3 strategies. This “success trap” typically arises not from willful inattention but from the overwhelming power of success that the past has brought.

The most pernicious effect of the success trap is that it encourages a business to suppose it already knows what it needs to know in order to succeed in the future. But that’s not true. Organizations that do not continuously learn new things will die.

Like most other forms of popular entertainment, Hasbro competes in a “hits-based” industry, launching many new products in the hope that one or more will become the sort of breakout platform or franchise that vastly overcompensates for the cost of developing products that don’t hit it big. Over the years, Hasbro has had its share of legendary hits (Mr. Potato Head, G.I. Joe, and Transformers), each becoming a growth platform. But until twenty years ago, the company had continued to see itself as a toy and game manufacturer for the retail channel.

The Hindu Roots of the Three-Box Solution

In the Hindu faith, the three main gods are Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma. Vishnu is the god of preservation, Shiva is the god of destruction, and Brahma is the god of creation. This triumvirate of familiar Hindu deities corresponds to the work of sustaining a thriving business. Like Vishnu, the firm must preserve its existing core; like Shiva, it must destroy unproductive vestiges of the past; and like Brahma, it must create a potent new future that will replenish what time and circumstance have destroyed.

Hindu myth makers paired each of the three gods with symbolically relevant wives. Vishnu’s wife is Lakshmi, who bestows wealth, just as Box 1 produces current profits. Shiva’s partner is Parvathi, who symbolizes power, a vital Box 2 necessity when selectively destroying the past. Brahma is betrothed to Saraswathi, who symbolizes creativity and knowledge—the critical inputs for Box 3 innovations and the wellspring of future profits.

According to Hindu philosophy, creation-preservation-destruction is a continuous cycle without a beginning or an end. Each of the three gods plays an equally important role in creating and maintaining all forms of life. Further, Hinduism states that while changes in the universe can be quite dramatic, the processes leading to those changes usually are evolutionary, involving many smaller steps. Consistent with this philosophy, the work of sustaining an enterprise is a dynamic and rhythmic process, one that never ends.

I have never before encountered an organization that has encoded the Three-Box Solution into its organizational scheme as explicitly as Mu Sigma, a rapidly growing decision sciences and big data analytics firm with headquarters in Chicago and an innovation and development center in Bangalore, backed by Sequoia Capital and General Atlantic. Inspired by his grandmother’s narration of stories from Hindu mythology, Mu Sigma founder and CEO Dhiraj Rajaram has used the three main deities of the Hindu faith to conceive a sustainably harmonized approach to the cycles of preservation, destruction, and creation.

The company divides its leadership into three “clans”—the Vishnu (preservation), Shiva (destruction), and Brahma (creation). On the company website, the leadership team members are explicitly designated Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma. The designations are not arbitrary. They are based on an assessment of the natural propensities of each leader. The expectation is that having explicit roles will help the cause of harmony among the three boxes.

The three clans engage in a dynamic, cyclical process of challenge and response. According to Rajaram, “There is a contest among the clans, with each one testing the other to provoke the most rigorous defense of its plans and ideas.” Vishnu challenges Shiva over what to preserve versus what to forget; Shiva challenges Brahma over which new ideas are truly worth pursuing. “Only when each intended move is explored and challenged from every angle can the best solutions emerge,” said Rajaram. Creating the clans, he added, “was a way for the three-box concept to become ingrained in the company culture. It is the constant engagement of these three that helps organizations to benefit from change.”

The risk for a business of Hasbro’s type is that it could become complacent, resting on its laurels and perhaps failing to notice changes in the environment that could threaten a formerly secure business model. That is why organizations must develop the Box 2 capacity to overcome the influence of the past, to divest one identity in favor of another.

That said, one thing Hasbro has going for it is a history of executing sudden and startling mutations. Founded in the 1920s by three brothers named Hassenfeld, the company was first a textile-remnants business but soon began to manufacture pencil boxes and other school supplies. When its pencil supplier raised prices, the company began manufacturing its own pencils, a successful enterprise that lasted into the 1980s and provided profits that funded other products and ventures. Coinciding with the postwar plastics revolution of the 1940s, the company launched its earliest toys (doctor and nurse kits with play stethoscopes, thermometers, and syringes). Mr. Potato Head debuted in 1952.

Businesses less metamorphic than Hasbro may face a steeper climb to develop their Box 2 disciplines. The work of Box 1, being founded on past success, is typically structured according to the operational disciplines engendered by that success. The fruits of success are real and the demands to sustain them are constant. From this defining DNA, firms create their systems, processes, and cultures. These structures shape the way an organization approaches everything it does: how it hires, promotes, invests, measures performance, formulates strategy, and evaluates ideas and opportunities. Linear ideas (those that conform with the past) tend to be adopted easily, whereas nonlinear ideas (nonconforming and therefore both uncertain and threatening) tend to be rejected easily.

One of the practical implications is that you don’t want Box 1 teams being distracted from their performance goals—and they don’t want to be distracted from the goals either. The general manager of MeYou Health, Trapper Markelz, told me about the time his company tried to use the “core” sales team to sell a radically new product:

In 2014 my Box 3 dedicated team had a powerful new product. Initially, we used the [shared corporate] sales team, but it was not prioritizing our product because it targeted different customer segments at a different price point. Sales were lagging significantly behind targets. Before learning about three-box thinking, I believed this to be a training problem. After three-box thinking, I came to understand the challenge: my business unit was asking the sales team to do different (Box 3), while the rest of the company was asking them to do more (Box 1). We can’t expect them to do both. So I proposed to the CEO that we fund the creation of a separate sales and marketing team for my business unit.

This is the trap that past success can engender. Ideas that differ substantially from those we are accustomed to almost always struggle to take root. As much as we might pay lip service to the fact that the future will differ dramatically from the past, we often behave as though it will be exactly the same.

Had Hasbro continued to see itself as a toy and game manufacturer whose customer relationships existed only at the retail point of sale, it would not be the successful company it is today. In the intervening decades, it transformed itself by shedding its old identities. That is among the many reasons why Box 2, whose mechanisms explicitly target success traps, is such an important enabler of Box 3 innovation. Later on you will see, in the example of United Rentals (chapter 4), that Box 2 disciplines can sometimes also be useful in helping to reconceive the way the Box 1 performance engine executes the core business.

Linear and Nonlinear Innovation

Another challenge you will have in balancing the three boxes is that Box 1 and Box 3 require distinctive forms of innovation. Leading innovation calls for fundamentally different management approaches in the two boxes. That’s why it is critical to distinguish between the respective types of innovation.

There are many typologies used to classify innovation: Innovations can be sustaining or disruptive. They can be incremental or radical. They can be competency enhancing or competency destroying. They can relate to product or process. However, I divide all innovations into two main types:

- Linear innovations improve the performance of your current business model. As such, they are part of the work of Box 1. For example, Hasbro developed Star Wars–themed versions of two of its classics: the game of Monopoly and Mr. Potato Head (“Darth Tater”). Both were brand extensions within an essentially unchanged business model. This type of innovation builds on the present core, making use of Box 1 knowledge, systems, and structures. Linear innovation is thus straightforward, unambiguous, and unthreatening to the status quo.

- Nonlinear innovations, the domain of Box 3, create new business models by dramatically (1) redefining your set of customers, (2) reinventing the value you offer them, and/or (3) redesigning the end-to-end value-chain architecture by which you deliver that value. As you will see, Hasbro executed variants of all three approaches, offering new value to new sets of customers across a dramatically redesigned value chain.

Preparing for Futures You Cannot Predict: Planned Optimism, Weak Signals, and the Daily Built Future

As the cliché asserts, “Fortune favors the well prepared.” Equally true is that misfortune afflicts the unprepared. Partly because their energies are overinvested in the Box 1 present, leaders often find it difficult to remember that the future is now. It is built day by day, a little at a time, beginning with what you do today that adds something new to what you did yesterday. Karan Gupta, managing director of IE Business School, told me that using the three-box framework has had an impact there:

Though the three-box idea is simple, it is extremely difficult to put into practice. Getting out of one’s daily activities and focusing on the future is easier said than done. However, applying the three-box model produces major impact. Constant reminders and the promise to “look in the mirror every day and ask oneself what one has done in Box 3 today” have helped our managers to excel in their daily activities and focus on the future. I noticed a remarkable change in managers. They performed their daily activities more efficiently so that they could free up time for Box 3 ideas.

Daily investments in Box 3 activity prepare you for whatever the unknowable future brings—good or bad. Failing to make those investments will likely result in a disappointing or endangered future.

Why is it so difficult to practice this simple lesson? Because when you neglect the future today, you don’t see the damage today.

Consider a Box 3 activity for an individual: doing regular exercise to ensure future health. Executives with hectic travel schedules commonly find it difficult to sustain an exercise routine. Everyone knows that travel can be draining. Since a single day’s failure to exercise exacts what feels like only a trivial cost, it is easy to choose not to go to the hotel fitness room to exercise. However, the costs of this choice accumulate over time, leading to a future of declining health in the form of added pounds, greater unrelieved stress, lower energy and endurance, and perhaps the higher risk of a serious illness.

As with the failure to make ongoing investments in personal fitness, businesses that do not attend to their own futures day in and day out are likely to be surprised eventually by a crisis—one that may have been brewing for years. On the other hand, if you proactively attend to the future every day, you earn the opportunity to shape the future to your advantage. Businesses must develop an active innovation culture through what I call planned opportunism. Planned opportunism is about a set of leadership behaviors and actions that prepares you for the futures you cannot predict. In practice, that means building an assortment of forward-looking competencies and embracing the disciplines of experimentation that create the flexibility to both pursue and shape the unexpected opportunities that come your way. The issue is not one of predicting the future; it is about being prepared for circumstances you do not exclusively control.

Planned opportunism is one of the Three-Box Solution’s most important concepts. It is a way to compensate for unpredictability of all kinds—good and bad. A simple example of this lurks in an observation that many business thinkers have made but which most organizations find difficult to put into practice: businesses that make across-the-board cuts, including cuts to strategic activities, during a downturn recover less resiliently than those that make more targeted cuts or even increase their investments in key Box 3 initiatives. In the latter case, it is planned opportunism that allows a business to deal with difficult circumstances by acting from a position of strategic confidence rather than one of fear or panic.

Institutionally, Hasbro became quite good over the years at practicing planned opportunism. I have included in table 1-2 a list of strategic discontinuities—diverse nonlinear changes relevant to Hasbro’s competitive environment—that occurred during the years between the mid-1990s and 2015. How likely is it that the Hasbro of twenty years ago could have predicted all of these changes? Not very. But it would have been able to generate informed hypotheses pointing in productive directions. To do that would have required a level of insight formed in part by what futurists call “weak signals.”2

Twenty years of strategic shifts in family entertainment, 1995–2015

| Technology | Family entertainment concepts | Retail channels | Demography | Globalization |

|

Proprietary gaming systems/platforms

Robotics Rapid growth of internet and wireless, evolving to dominant entertainment channel Handheld digital devices and media (cameras, smartphones, tablets, etc.) Shrinking product life cycles plus rapid technology advances put intense downward price pressure on technology-based games. |

Families spend less time playing together; play is thus more age segmented. Parents in two-income households spend less time with children but have more money to entertain children. Parents prefer toys and games that offer enrichment value. Many children are hyper-scheduled and have less leisure time; when they play, they are often by themselves and prefer fast-paced video games. |

Big-box stores drive retail consolidation, crowding out small mom-and-pop and boutique outlets. Large retailers drive economies of scale, demand high levels of supply chain integration. Big players offer private-label products. Bankruptcy of “traditional” competitors leads to further consolidation. |

Children “grow older younger,” lose interest in traditional toys at an earlier age. Aging population makes grandparents a powerful buying segment; they often “own” play activities with grandkids. Adults find opportunities for play in social and/or work settings (gaming as a strategy or simulation tool). Growing minority populations soon gain majority status. |

Potential growth in emerging markets, where concepts of play are different and disposable income is low. But … … in emerging markets, new approaches to product design, manufacturing, and marketing will be needed to overcome cultural, market, and logistic barriers. Thus, Western firms need to build new competencies. Growth potential in developed markets can be pursued through existing competencies. |

Weak signals consist of emergent changes to technology, culture, markets, the economy, consumer tastes and behavior, and demographics. As the term suggests, weak signals are hard to evaluate because they are incomplete, unsettled, and unclear. But they are the raw material for developing hypotheses about nonlinear changes in the future. Hasbro devised a method for tapping weak signals and using them to make inferences about possible futures that might develop.

The process starts with these three basic questions:

- What particular factors and conditions does one’s current success depend on?

- Which of these factors might change over time or are changing already, thus putting current success at risk?

- How can one begin to anticipate and prepare for these possible changes so as to cushion or even exploit their impact?

Having answered these questions, Hasbro over time was able to make what in retrospect were smart, nonlinear moves toward an unpredictable future. No matter what business you’re in, you will benefit from being active rather than passive when dealing with time and change. That is the essence of the Three-Box Solution.

As Hasbro looked toward the future, it was able to anticipate some of the discontinuities. For example, the fact that both parents in many households held full-time jobs was already the US norm. Less clear was what that implied for the concept of family entertainment. A falling US birthrate meant Hasbro additionally faced a shrinking customer base. The company might also have seen the growing demographic diversity of its US customers. And as globalization accelerated, it might likewise have developed an appetite for the growth potential in markets around the world.

Similarly, there were weak signals even in the 1980s—the Atari video game and the personal computer revolution, for example—that gave early warning that technology would disrupt the gaming space. However, twenty years ago, there were significant unknowns about the evolution of technology-based gaming:

- How quickly would the internet become a potent channel?

- How could companies combine physical and virtual realms for their consumers?

- Who would be the new competitors in this space (Electronic Arts? Nintendo? America Online? Sony?)?

- Who might be potential new partners (Marvel Comics? Pixar?)?

- Would the PC remain the predominant platform for home technology or would a new one (mobile phones) or an old one (television) supersede it?

- What would be the new economic model when the industry moved from “analog dollars” to “digital pennies”?

Balancing the Three Boxes: Experiment to Grow Knowledge and Shrink Uncertainty

Across domains riven with uncertainty, the best way to address questions like those Hasbro faced is by conducting low-cost experiments meant to test critical unknowns en route to conceiving scalable new business models. As Goldner noted, “You must probe and learn to achieve clarity in embryonic markets.” (As you will read in chapter 3, IBM’s emerging business opportunities process was heavily focused on learning about technology markets so new that, like planets cooling from clouds of gas and debris, they were not yet fully formed.) In such circumstances, the experiments that arise from inferences based on weak signals must be accompanied by robust hedging strategies.

Experimentation is all about learning, but if you can’t forget, you’re unlikely to learn. To succeed in Box 3 creation, you must first excel in Box 2 destruction. The work of Box 2 often comes down to making key distinctions between values that are timeless (enduring for the long run) versus those that are timely (ultimately perishable with the passing of time). Think of roots and chains. If you cut a tree’s roots, it dies. Therefore, leaders need to understand that their organizations’ roots have timeless value and need to be preserved. Conversely, every organization also accumulates chains consisting of once-timely ideas and activities that have lost their usefulness. If you do not find and break the chains, they will keep you from getting to the future.

Organizations need to test ideas for new lines of business both for their alignment with timeless values and for the timeliness of the opportunities they present. Part of the benefit of developing a process for making such judgments lies in its capacity to help enterprises stay centered within their mission and vision.

Hasbro has never lacked for creative ideas, but one of its ventures in the 1970s offers a cautionary tale about getting ahead of oneself. In 1970, when wild adventures in diversification were in vogue across many industries, the company launched a chain of nursery schools under the Romper Room brand (made famous by a popular children’s television program). There was an element of timeliness to the idea; the administration of President Richard M. Nixon had recently begun a program of child-care credits. Moreover, Hasbro believed that the schools would build on its successful line of Romper Room–branded toys. But when a product company jumps into a service business, it risks violating a timeless value and venturing out of its depth. That’s where Hasbro found itself. “We’d get phone calls saying, ‘We can’t find one of the kids.’ The whole company would stop,” Alan Hassenfeld, a member of Hasbro’s founding family, told the Wall Street Journal in a December 13, 1984, article. After five years of a bold but ill-advised strategy, Hasbro exited the nursery school business.

Not every nonlinear idea will be right for your business. Part of a sound hedging strategy when experimenting with nonlinear ideas is to assess how far may be too far to stretch your existing business model and internal skills. By 1970, Hasbro had settled into being primarily a maker of toys. As it considered the Romper Room nursery-school idea—notwithstanding the brand leverage it stood to gain through the schools—Hasbro could have concluded that its internal skills and culture didn’t suit the demands of an early-childhood-education business model (whose degree of difficulty it may have underestimated). Getting out of the business required recognizing that the unfamiliar business model had taken Hasbro too far from its timeless center.

Balancing the Three Boxes: Structure as a Lever to Unlock New Value

“Box 2 is the most challenging in a company like Hasbro that’s been around a long time,” said Goldner. (See the sidebar, “Hasbro’s ‘Forgetting’ Challenges in the Mid-1990s.”)

Hasbro’s “Forgetting” Challenges in the

Mid-1990s

In light of the nonlinear shifts identified in table 1-2, one can speculate about several core assumptions that Hasbro needed to selectively forget to ensure future success:

- We are a product company.

- We make analog-based games that have long product life cycles, command premium prices, and generate high margins.

- We distribute through brick-and-mortar retail outlets.

- Our consumers are kids fifteen years old and younger.

- We make board games that promote face-to-face social interaction in a physical setting.

- We are an American company.

- And so on …

The key to a successful strategy of forgetting may turn out to require shaking things up by changing the organizational structure. Goldner remarked, “Hasbro was historically very siloed. So one of the first things we did [in the early 2000s] was move away from manufacturing categories toward a brand orientation under global brand leaders. This was a Box 2 move; we had to forget how we operated in the past.” (Structural changes may sometimes be a necessary prerequisite to initiating programs of nonlinear innovation. In chapter 6, Mahindra Group CEO Anand Mahindra describes how changing the diversified company’s organizational structure unleashed new market potential and a more entrepreneurial culture.)

Organizing around brand platforms gave Hasbro managers both the accountability and the authority to pursue myriad brand opportunities. And planned opportunism prepared the company to be flexible in developing strategies that could meet head-on the various changes in technology, demography, generational behavior, and global opportunity it already had identified.

In 2000, Hasbro had little presence in emerging markets. Since then, it has invested aggressively and now earns more than 50 percent of its revenues from non-US markets, including significant revenues in emerging markets. The company has increased its emphasis on digital gaming. Hasbro’s global brand teams have leveraged core brands, such as Transformers, across multiple platforms: toys, movies, television, and the internet (including social media). In 2000, Hasbro’s top-eight brands delivered 17 percent of total revenues; as of 2015, they accounted for more than 50 percent.

Between the end of 2000 and the first quarter of 2015, Hasbro’s stock price rose from $11 to $72. This represented a compounded annual growth of 14 percent in market capitalization in fifteen years, despite the turbulence of the dot-com bust and the Great Recession. In sharp contrast, the stock price of Mattel, Hasbro’s major competitor, increased from $15 to $25 during the same period. Even though Mattel exceeded Hasbro in sales revenue—$6.02 billion versus $4.3 billion in 2014—both companies had a similar market capitalization as of April 2015.

One of Hasbro’s strengths is the recognition that nonlinear initiatives sometimes require rebooting. In 2009, the company eyed the growing number of cable TV networks and chose to dive in, partnering with Discovery Communications to launch The Hub Network.3 The audience grew to roughly 70 million homes over four years. Even so, Hasbro decided to pull back from the investment in 2014, giving Discovery controlling interest in a 60/40 split. The move “incentivized [Discovery] to more fully support the network” while allowing Hasbro to “[generate] significant merchandise sales from TV shows built around My Little Pony, Littlest Pet Shop, and Transformers Rescue Bots that air on the channel,” said Goldner.

Hasbro added to its merchandising muscle by entering into a new agreement with Disney around the same time. Disney announced it was giving Hasbro global rights to manufacture dolls from its popular Disney Princess—eleven female characters, including Cinderella, Jasmine, Mulan, and Pocahontas—and Frozen lines. The agreement ended Disney’s nearly twenty-year relationship with Mattel and opened new horizons for Hasbro, whose target market had been tilting predominantly male. This strategic initiative leveraged Hasbro’s existing resources while still taking the company in a new direction.

Goldner has initiated innovations in structure and process to keep strategic thinking sharp and ensure that continuous focus is applied to Box 3 ideas: “We have a team called Future Now that works only on the future of our brands; they don’t think about how to sell the brand this year.” Hasbro also considers ways the boxes can intersect and provide mutual benefit. Goldner convenes what are known as “martini meetings,” so named because brainstorming at the meeting follows the shape of a martini glass. “We start at the rim, as far out as we can, and think about emerging technologies and new inventions. Real Box 3 thinking. Then we narrow these ideas down to those that are most promising. As we move closer to the stem, we see how those technologies can be applied to our current product lines.”

New business structures are often indispensable to giving shape, method, and discipline to managing the boxes in concert. For both better and worse, organizations optimize around their core successes. It makes great sense to do so. But you must also create oases where you direct regular systematic focus beyond the near horizon of Box 1. Otherwise, lacking ready access to weak signals, your future will be starved of nonlinear ideas to develop. Regular meetings and deliverables make it more difficult to slide back into a habit of neglect.

The key point to take away here is that Hasbro has learned to see value in all three boxes, understands that they are interrelated, and has taken formal steps to ensure each gets the necessary attention.

Keeping It Simple: Basic Principles of the Three-Box Solution

Oliver Wendell Holmes is said to have observed, “I would not give a fig for the simplicity on this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.” The meaning of this quote is frequently debated, but I take it to mean that Holmes judged an idea or a tool by its ultimate effectiveness. Until it shows its mettle, he doesn’t give a fig; he remains a skeptic. I use the quote to suggest that this book will show how this simple framework can prove its mettle by helping you tame the apparent complexities of leading innovation. The denser the tangle, the more useful the tool.

The deceptively simple Three-Box Solution has only a handful of principles:

- You should engage in both linear (Box 1) and nonlinear (Box 3) innovations to ensure leadership in the future.

- Success in Box 1 is the primary inhibitor of taking bold action in Box 3. You must develop the discipline of selectively forgetting the past (Box 2) or the past will prevent you from creating the future.

- Optimizing current business models in Box 1 and creating new business models in Box 3 must be pursued simultaneously, yet they call for different activities, skills, methods, metrics, mind-sets, and leadership approaches.

- Managing the three boxes is a journey, not a project. Businesses fail at it when they are sporadic rather than continuous in seeking balance. Like gardens that need regular watering and weeding, each box requires ongoing attention.

- Don’t think about the future as a far-off time. The future is actually now because you are building it day by day.

The next five chapters draw on varied examples, including a coffee-roasting and beverage-brewing company, a global network of Protestant churches, and a large equipment-rental business. Each is distinctively accomplished in using one or more of the three boxes, and a couple of them are exceptional at keeping all three in balance. Most have faced powerful “forgetting” challenges. None of them would ever claim to have all the answers; indeed, the work of trying to sustain balance is automatically humbling.

We will look at the three boxes one by one in the next three chapters, moving from the future (Box 3) to the past (Box 2) and returning to the present (Box 1). The Three-Box Solution is a concept to communicate the balance of leadership for the here and now, forgetting the past, and creating the future as a three-ringed circus occurring simultaneously. We return to the theme of balance across the three boxes in chapters 5 and 6.

At the end of each chapter, you’ll find takeaways that distill the core message in a way you can share with others in your organization. A tools section, also at the end of every chapter, includes discussion points, questionnaires, and activities to help you and your team apply the ideas and develop your own Three-Box Solution.

We begin with the future (Box 3) in chapter 2 because the future is about creation, and creation not only precedes everything else, but the task of creating the future really is where the problem of balance lies. You’ll want to start with a cup of strong coffee.

Takeaways

- Do not distract those who work in the core Box 1 business from their demanding performance goals. Box 1 cannot execute Box 3 innovations. And that is OK. Remember that Box 3 cannot exist without Box 1. Also, what must be forgotten for the purposes of Box 3 may still be vitally important to Box 1.

- Box 2 is the indispensable element of the Three-Box Solution. Most organizations ignore Box 2 as they try to innovate their way to a new model. Even as old ideas and practices choke off the new future they’re trying to create, organizations find it very difficult to overcome the power of the past. The more attention a company pays to Box 2, the more room there is for the Box 3 to achieve its goals. If Box 3 were an NFL quarterback, Box 2 would be the offensive line, providing time and flexibility in which to read the defense, execute, and, if necessary, improvise. Without a well-functioning Box 2 discipline, your Box 3 offense will be stagnant and predictable.

- Good Box 3 hedging strategies are important. In a regime of experimentation and learning, not every step along the way will be successful. You need to develop a process for hedging risk. That typically means testing assumptions through iterative learning stages that, over time, resolve uncertainty and either produce growing confidence or reveal the need for a reboot or exit. Hasbro’s 1970s venture into Romper Room–branded nursery schools might have benefited from better testing and hedging.

- Create formal processes that both serve the goals of Box 3 and increase the likelihood of achieving balance among all three boxes. Sustainable Box 3 activities require both structure and accountability. Hasbro CEO Brian Goldner inaugurated “martini meetings” and the Future Now team to keep Hasbro moving forward on Box 3 ideas. The martini meetings served the further purpose of identifying situations in which the three boxes might intersect. This became procedural reinforcement of the boxes’ relatedness and ultimately contributed to balance. On a personal time-management level, Goldner audits the amount of attention he devotes to each box every week.

- Think of the Three-Box Solution as endlessly cyclical. You are always preserving the present, destroying the past, and building the future. In other words, the business models, products, and services you create in Box 3 will at some point become your new Box 1.

- The Three-Box Solution imposes on leaders a requirement for humility, because it is essentially a strategy for taking action through continuous learning. Learning is intrinsically a humbling activity; to learn is to admit you don’t know everything. Almost every aspect of the Three-Box Solution framework is intended to increase opportunities to listen and learn. In my experience, the most effective leaders also happen to be good listeners, are never arrogant, and are able to disregard rank and status in the service of finding the best ideas. The examples in later chapters will bear this out.

Tools

Tool 1: Assess Your Business

Crafting Three-Box Solutions will require you to look at the way your business operates through a new lens. The starting point is to understand the way things operate now. For instance:

- How easy or difficult is it for your business to generate, refine, incubate, and launch new business ideas?

- Has your company, business unit, or functional department developed ongoing processes for identifying emergent trends, based on weak signals, that are likely to affect your business in the coming years?

- Describe your current planning process. Does it incorporate the voices of maverick thinkers? Does your population of mavericks feel empowered or, conversely, stifled?

- Describe your current method for resource allocation. Does it earmark funds for high-risk projects?

- Describe your current performance management system. Does it support experiments with unknown outcomes?

- Describe your current approach to talent acquisition. In addition to keeping Box 1 well stocked, do you also recruit talent that would support tomorrow’s business?

- What particular factors and conditions does your current success depend on? Which of these factors might change over time, thus putting current success at risk? Do you have formal processes to anticipate and prepare for these possible changes so as to cushion or even exploit their impact?

- How much time does your management team currently spend on Box 1 versus Boxes 2 and 3?

- What barriers prevent your management team from spending more time on Boxes 2 and 3?

Tool 2: Identify Weak Signals

After diagnosing your current situation, initiate conversations around Box 3 thinking. As a management team, identify the weak signals that potentially could transform your industry in the future. In particular, reflect on:

- Customer discontinuities. Are today’s biggest, fastest-growing, or most profitable customer segments likely to be the same ones in ten to fifteen years? Who will be your customers in the future? Are there small or emerging customer segments today that are using or even customizing your products or services in unconventional ways? Which nonconsumers today could potentially become consumers in the future? What would be their priorities?

- Technological discontinuities. What disruptive technologies can open up new opportunity spaces?

- Nontraditional competitors. Are today’s most potent competitors likely to be the same ones in ten to fifteen years? Who will you be competing against in the future? And on what basis?

- New distribution channels. Will there be fundamental changes in your go-to-market approach in the future? What possible supply-chain economies (or diseconomies) might your business face?

- Regulatory changes. What are the potential regulatory reforms? What new opportunities might they open up for you?