Chapter 7

COMMUNICATION

It’s evident that “organizations aren’t the visible, tangible, obvious places which they used to be” (Handy 1997, p. 378). Communication distribution systems—in other words, the technologies people use to communicate—are now an important force in effective internal and external organizational communications. As technology continues to improve and becomes less expensive to implement, virtual organizations will become the norm.

Effective personal and organizational communication is critically important in a virtual project management organization (Cascio 2000; Duarte and Snyder 2006; Scholz 1998). It is also complex, because organizations are not the traditional brick-and-mortar places that they were in the past (Handy 1997, p. 378). On the advice of organizational theorists, organizations of the past often continuously monitored team members; now, many organizations realize, or will realize, that it is not necessary to “own all the people needed to get the work done, let alone have them where they can see them” (Handy 1997, p. 378). Ideally, the continuous monitoring of project team members would no longer be required, because in a VPMO, individuals own their processes, and they need to be left alone to get their jobs done. Virtual project organizations must shift from the traditional structure of single-person leadership to a focus on individuals’ ability to lead and manage themselves (Cascio 2000).

Some people believe that virtual communication will lead to chaos. Technology allows people to access information instantly, and people enjoy many different communication options. In today’s business world, face-to-face communication and even telephone calls are less common because other means and methods of communication are available and convenient. It is a lot easier to send a quick email at 9:00 p.m. to a colleague than to pick up the phone to give her a quick update on a project.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN A VPMO

A traditional team communicates directly through face-to-face contact. Body language, other visual cues, and tone underscore meaning (Duarte and Snyder 2006, p. 142). Virtual teams, of course, must rely on indirect communication in the form of telephone calls, emails, faxes, and other technologically based methods (Duarte and Snyder 2006). Personal contact will always be essential, but it does not require being physically proximate. Continuous contact, more than proximity, is what bonds people together. The virtual project management office can operate with less face-to-face communication, although direct contact is still the best way to facilitate effective communication.

Imagine what it would be like to be on a submarine that has no contact with anyone outside of the selected few on board. What kind of relationship might these individuals have with the outside world? How connected would these people feel after a few months without contact? Think of the people on a virtual team as being on that submarine. Each person has a job to do and a mission to accomplish, but without some access to information from the outside world, they may feel detached and alone. The job of the project manager is to be the bridge for these people to the outside world. He or she must make those people feel connected to the project in such a way that they feel valued and trusted.

Best practice: Designate time each week to reach out to the more distant members of the virtual project management organization. Give peripheral stakeholders a short, personal update on the project. After the update, ask what they think about the project. (Keep in mind that the view of the earth from Pluto is vastly different from the view of the earth from the moon.)

Even though “people can work together connected only by phone, fax, or E-mail” (Handy 1997, p. 378), the virtual project manager must realize that technology cannot make up for poor or lacking communication. Experts agree that the virtual environment requires that communication be clearer and more concise. Reach also is important. Email, blogs, and texts can be important tools, but they have to reach people at all levels of the organization if they are to be effective. Hence, the project manager must learn not only to communicate more, but also to improve the distribution of information.

Figure 7-1 details some of the reasons organizational communication either works or doesn’t. Ineffective communication may be either too intense or not intense enough in terms of the volume, or amount, of communication; its substance; its type; or its quality.

Figure 7-1: Evaluating the Quality of Communication

Real communication is about distributing important information. Project managers should not simply act like messengers. Simply passing along information via email is not real communication; this does nothing to ensure comprehension, nor does it foster connections between people. Project managers should use information as a way to build a rapport with others—in other words, to create trust. It does not take much time or effort to add a few explanatory words to an email. Make communication important and make it count.

Best practice: Everyone in the VPMO must remember that communication is very important. Make communication effective at every opportunity. Shun just passing along data, and embrace passing along tangible positive experiences. Will we remember those who liked us the most, or will we remember those who sent us the most emails?

CHALLENGES

Technology is the link between the individual and the virtual project management office, requiring the organization to carry the burden of a dispersed information technology infrastructure to maintain its remote sites. The virtual organization’s dependence on technology can lead to technical challenges that may exacerbate communication issues (Cascio 2000; Karl 1999) caused by the lack of robust personal contact that comes from day-to-day physical proximity and interaction.

Working across great distances may require working with people in different time zones, from different countries and cultures, and who speak different languages (Karl 1999). Roberts, Kossek, and Ozeki (1998) found that executives dealing with virtual projects were challenged by having to disseminate innovative, “state of the art knowledge and practices” throughout the organization while trying to overcome the fact that although English was the language of business for all the companies within the study, English was not the native language of everyone working on the projects.

Best practice: Respect the schedules of stakeholders in different time zones and schedule meetings as fairly as possible.

People in virtual project management organizations may feel isolated because they do not have the same opportunities for casual social interaction around the coffee maker or water cooler that people in traditional companies do. These social interactions include, on the positive side, the passing on of vital organization information and information on others’ activities, and on the negative side, the passing on of rumors about the organization. Both types of communication are necessary, as even seemingly negative interactions create an atmosphere of connectedness to the organization.

To avoid isolation, team leaders must harness technology to facilitate contact and keep individuals in the loop (O’Connor 2000; Cascio 2000). To encourage good communication, the virtual project manager should ensure that all team members have compatible technology. The virtual project also should quickly organize databases that allow sharing and learning. Duarte and Snyder (2006) recommend establishing “shared lessons, databases, knowledge repositories, and chat rooms” (p. 17) to enhance virtual teams’ learning and communication opportunities.

COMMUNICATING WITH STAKEHOLDERS

The first and most important element of communication is actually doing it. There are many reasons for the failure of organizational communication, but one of the simplest reasons is that communication is not happening often enough. Companies spend billions of dollars each year on communication technology—only for people to act as if they do not have time to put together a meaningful, accurate project status report (yet they seem to have time to post tweets or update their status on Facebook). One possible reason is that it is more fun and interesting to chat away with friends than to talk with people whom one is less familiar with or worse, with someone that one is afraid of.

People spend many hours with others at work, yet our colleagues can be the hardest people to communicate with. Why is this? One reason is that usually, more is at stake in work communications. Friends rarely beat us up for missing deadlines or not always having exact change to cover lunch. But it’s difficult for a project manager to report to clients that a project is running late or over budget. One cannot make everyone in the project a friend, but at least one can make their interactions with others interesting and productive. The less reluctant people are to communicate with each other, the more communication will actually happen.

Virtual project management leaders need to make sure they are communicating with all of the relevant individuals on a project. To determine who the stakeholders for a given project are—in other words, who needs to know what is going on—start by doing a communication assessment. Use Figure 7-2, which lists categories of stakeholders with whom you may need to communicate, as a guide.

Figure 7-2: Common Project Stakeholders

Once the stakeholders have been identified, determine whether the relationship between your organization and the stakeholder is contractual, organizational, or informational. If there is a contractual relationship, the individuals and groups involved need at a minimum certain economic and milestone-related data. Communication with this group should include detailed information about contract milestones, contract changes, contract payments, and the project timeline (schedule). Uncertain whether your organization has a contractual relationship with a stakeholder? Just follow the money. For example, even though a subcontractor of your supplier is not given a check with your company logo, if you follow the money trail, there is no doubt that there is a contractual type of relationship between your organization and the subcontractor.

There is an organizational relationship if there is some kind of organizational connection between the project manager and the other individual or department. Usually these kinds of relationships are obvious because they are shown on an organizational chart. Follow the lines on the organizational chart—if there is a connection, then the relationship is organizational. If this is the case, you need to offer the same information you would if there were a contractual relationship, but your updates should also include any greater implications of the project as it relates to the company. For example, if it is necessary to complete your project before another project can start, you must make sure that stakeholders know this so that they’re aware of the ramifications of a delay in your project schedule. In short, you must explain the bigger picture so that others will understand the situation.

If the relationship is not contractual or organizational, it should be informational. In an informational relationship, updates should be kept as short as possible. Use them to highlight the project team’s achievements. It is important to keep groups with whom you have an informational relationship apprised of progress, but you do not want to pass along too many details. Details create questions, and questions create more questions, and this will result in your spending more time on updating these stakeholders than is necessary. Project managers who spend too much time communicating updates and general information are at risk of falling into the virtual project management information time trap, discussed later in this chapter.

Best practice: Consider mapping the lines of communication for all of a project’s stakeholders—in other words, study their interactions and how they overlap. The web of communication is very important in a virtual project management organization because of the value of open communication. Understanding how communication operates within a team is important for project success.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE AND COMMUNICATION

Anyone who has spent time in an organization is familiar with a standard organizational chart. Lines and boxes connect people together in a manner that shows the reporting structure of the organization. However, an organizational chart does little to show the actual communication structure of the organization. In the practical world, few organizations are rigid and structured enough to have clear lines of direct communication such as those seen on an organizational chart.

Because the lines of communications may be blurred, in most organizations individuals piece together information to create the big picture. The rumor mill is often a good source of information. There are always individuals who are so connected they learn things sooner than others. Find out who these organizational listeners are and ask for their perspective. A virtual project management office may spend a lot of money and time communicating the organizational vision, but that might not be the most effective manner to communicate other information. So it is important that individuals learn how to assimilate all of the incoming data and create a view of the organization that is consistent and accurate. If people have an alternative source of information, then the official channels might not be as effective.

In the VPMO, it is also important that individuals and leaders come together to create creative, independent groups that have individual and specific purposes. One may want to fault the organization for not providing a road map for doing so, but the reality is that these kinds of connections need to develop naturally. If they are forced, communication may become stilted, and weak communication is one reason that people resist change.

Best practice: There should be a way for feedback to be passed along to the highest levels of the company without any filtering layers. Project managers do not need to report to top management, but there must be a mechanism for project managers to be heard. Consider asking the CEO to meet informally with different project managers to gather their thoughts on ways the organization can improve.

Think of an organization like an onion instead of like a hierarchical grouping of lines and boxes. The sections of an onion are so tightly pressed together that the onion appears to be a solid ball, but each layer is really connected only at the base. The layers are similar to each other, but each layer grows at a different angle and the layers are different sizes so that they can fit into one another to create what looks and feels like a solid sphere from the outside. This onion metaphor helps us better understand how individuals in an organization are connected. An individual is like a layer of the onion, connected to the whole, but completely different from the other layers. It is critically important for the leadership in a VPMO to recognize these different human constructs. Leaders who do are better equipped to move their organization from homeostasis towards a particular goal.

People want to retain their individuality without losing their identity, and they also want to be part of a greater whole. On the surface, this appears to be a paradox. People in virtual project management organizations must learn to work in conjunction with one another, yet each member of the team can and should make his or her own bold contributions to projects. Individuals can achieve a sense of connection to the projects they work on by integrating part of themselves into their work. A clothing designer, architect, or artist gives a little of herself with every piece of work; everyone wants to have that same sense of creation. Once a project team member has done his part of the work, he must pass the baton along to someone else, who will then add her own perspective to the project in progress.

Consider creating, developing, or evolving flexible and open systems of communication that will be responsive to new situations. Organizations that will be successful in the future are those that are tightly integrated without being codependent. In the past, organizations strove to be like an apple, a homogenous mass, completely solid, with no room for sudden change. Now organizations must strive to be more like an onion, with layers that fit together neatly, to remain resilient and flexible without losing sight of the whole or the individual.

Best practice: Reflect on the fact that organizations should be more like an onion than an apple. Consider how the structure of the organization might affect organizational communication.

Best practice: Always consider how you communicate with others in the organization. If people are fairly close by, consider walking down the hall to talk with them rather than just sending an email. Visit vendor locations to see how they operate and observe their processes. You can learn more from talking face-to-face, so do your best to make personal contact whenever possible.

COPING WITH NEGATIVE COMMUNICATION

A three-step process (see Figure 7-3) will help those working in virtual environments cope with negative communication. The process can also be used in traditional office environments, but it is applied differently. It is important to recognize the difference and to apply the correct techniques to the situation to avoid more communication problems in the future.

![]()

Figure 7-3: The Process of Correcting Negative Communication

First, you have to identify whether the negative communication is a face-to-face issue or a virtual issue. There are critical differences in the dynamics between traditional, collocated teams and virtual teams. A traditional team communicates directly, through face-to-face contact. People use the communication style they are most comfortable with to express dissatisfaction; people who like to vent in person are unlikely to send a negative email. Negative in-person communication should be responded to in person. Matching your response to the perpetrator’s style of communication will help ensure that the message is received.

What if the negativity is communicated virtually? Virtual teams, of course, rely on indirect communication in the form of telephone calls, emails, faxes, and other technologically based methods (Furst et al. 2004, p. 7). Keep in mind that the perpetrator of the negative communication may blame technology for creating a misunderstanding. As part of the process of addressing the negative communication, you must educate the individual in virtual etiquette and make it clear to him that future communication should be clearer and more concise. Avoid allowing him to blame technology, unless there is some real technical hindrance.

Furthermore, you need to follow up regarding negative communication. If no one follows up, you won’t have an opportunity to correct the process. Clarify what was negative about the communication, and replace it with something positive. The more you can eliminate negative communication, the better off the organization will be.

Best practice: Monitor the effectiveness of the identify > address > follow-up process when dealing with a negative communication issue, and determine what can be done better the next time.

Research indicates that virtual project managers, like brick-and-mortar ones, face conflict during the team forming and storming stages of the Tuckman model. Other research has emphasized that in the virtual environment, trust is essential for effective management. It can be reasonably concluded that a competent PM will gain the trust of team members (Duarte and Snyder 2006). Duarte and Snyder (2006) report that competent project managers are those who effectively communicate with customers and teams and set high expectations. Because the forming and storming stages are the first two phases of a project team’s life, the team has not yet been able to establish the necessary trust with the project manager. It may be helpful for the project manager to meet face-to-face (electronically or traditionally) with the team to demonstrate her competence, which should increase the trust quotient.

Best practice: Coping with negative communication is always challenging. Address people’s negativity quickly, concisely, and consistently. Doing so will help you create a positive culture.

DELIVERING CLEAR, DIRECT, AND CROSS-CULTURAL INFORMATION

The leadership of the organization is responsible for making sure that important information is delivered in a timely, clear, direct manner. Good communication is self-reinforcing because people will remember and use the content of the message. A message that is confusing or full of obscure technical jargon is not effective. Clear communication accurately communicates a message. It must be complete and devoid of vague references that could be misinterpreted. Direct communication clearly explains the message and the expectations for the person receiving the message. It is also focused on the topic at hand.

Best practice: Consider how many times you communicate with others in one day. How many of those communications could accurately be described as clear? What can you do in the future to make your communications clearer?

If the audience for a message is international, leadership must determine if the message will be effective cross-culturally. Clear communication is understood by everyone, regardless of their culture or native language. A message going to an international audience must be even better crafted than one that is sent to your immediate team. Just translating your marketing materials is not sufficient; the message must be communicated with the same level of clarity and passion as it is in English. If a message is vague and unclear or not meaningful to recipients from other cultures, you may need to create a new message that works well internationally. Keep in mind that culturally specific references, for example to American football or certain U.S. celebrities, will probably mean little to, and so fall flat with, international audiences. To get additional perspectives on an important project message or announcement before sending it out, consider asking multiple colleagues to review the message. Better yet, to ensure that the message is clear, consider asking reviewers from multiple countries for their feedback.

Best practice: When communicating internationally, consider using different examples to make the point clearer. Try to insert more relevant examples that will resonate better with individuals from other nations. Instead of examples pertaining to baseball, consider using soccer examples.

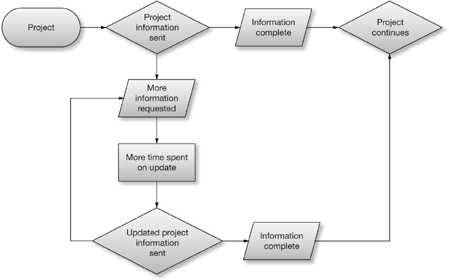

DELEGATING AND RELEGATING COMMUNICATION

Providing information often leads to questions, which lead to answers, which lead to more questions or a desire for even more information. On top of this, the nature of the virtual project management organization creates a need for more information. Because people in virtual environments lack the kind of water cooler social networking opportunities they would have in brick-and-mortar businesses, they also may not be getting as much information as they would in traditional offices. They may rely on the virtual project manager to answer questions and research more information, which takes time—time that virtual project managers should be spending on managing the project. These project managers may find themselves in what we call the virtual project management information time trap, illustrated in Figure 7-4.

Figure 7-4: Virtual Project Management Information Time Trap

A project manager who finds himself in this time trap must immediately regroup and consider the kind of information that is being distributed, either officially or unofficially, that is causing stakeholders to have so many questions. Excessive demands for more information indicate that the project manager is not providing enough regular updates, the project is starting to spiral out of control, or others in the organization doubt that the project manager will be able to complete the project.

Work needs to be done before one can communicate about it, so if the project manager is spending too much time on communication with stakeholders, he needs to review his process of communication. Communication should be the final step of the project process, after all of the process steps have occurred. The communication process is a way of taking credit for milestones and achievements. If one is spending too much time on the final link in the chain, one needs to find a way to make more work happen.

Best practice: Have you been caught in the virtual project management information time trap or seen someone who was? What was done to improve the situation?

To avoid the virtual project management information time trap or to get out of it, the project manager must follow a process of delegation and relegation. Here, delegation is the process of asking someone else to handle some of the communication regarding the project. Relegation is a way to better compartmentalize requests for information and to more efficiently communicate information and expectations about the information.

Delegation

Project updates should be a shared responsibility, not just something to be completed by the project manager. Once the reporting and informational requirements (framework) of the project information to be tracked have been determined, then the virtual project manager needs to decide who is responsible for gathering up the details.

When a project is being planned, the project manager should consider appointing a project historian. This is not a full-time position, nor does one person have to stay in the position for the life of the project. The project historian should ask everyone for informational updates about the project, and she should also gather information on what individuals and groups have done for the project. If stakeholders feel that they have the right to ask questions about a project, then they should be asked what they are doing to support the project. It’s natural for stakeholders to ask questions and voice concerns, but they should also be held accountable for their actions related to the project.

The project historian is a better person than the project manager to ask stakeholders what they are doing in support of a project, because if the project manager asks this kind of question, stakeholders may perceive it as annoying or confrontational. During the conversation, the project historian can use peer pressure in a positive way by talking about what other stakeholders are doing for the project. If you’ve ever had to raise funds for charitable organizations, you know that telling prospective donors that others have donated to the cause can help push them to donate. Stakeholder peer pressure can be an effective way to help gain more support for the project.

Best practice: Assign the project historian not only to chronicle the project, but also to create a repository of information that can be reviewed at the end of the project during a lessons-learned session. Subcontractors and consultants also should provide progress updates to be included in the repository of project information. This information can also be used to develop future projects of a similar nature.

Relegation

A virtual project manager needs to shape stakeholders’ expectations by relegating communication to the most appropriate time. The project manager should not drop everything to answer an email from a stakeholder. Even if you think that dashing off an answer will resolve the question quickly, it is better to wait. Quick responses rarely result in closure. Keep in mind the unwritten organizational axiom that emails that are answered quickly will always result in a follow-up question. Supposedly quick answers become time wasters when they create or do not resolve uncertainty.

SOURCES OF RISK

Uncertainty about what someone wants or is trying to say could be attributable to any of the five basic sources of risk related to communication, as given by Garrett (2007):

A lack of understanding

Shortcomings of language or interpretation

People’s behavior

Haste

Deception.

A Lack of Understanding

It is critical that communication regarding requirements and deliverables be understood by the recipient. Not all stakeholders will have the same level of knowledge about the project, so certain information, abbreviations, acronyms, or technical jargon might be confusing. A project manager must keep his audience in mind when crafting messages. Communication cannot succeed if the audience does not fully understand it.

Shortcomings of Language or Interpretation

Human language is complex, and verbal communication usually has elements of tone and body language that help us decode other’s meaning and intention. When people communicate virtually, body language cannot help convey their meaning, so the messages they send could be perceived as incomplete or confusing. Written communication can be interpreted in different ways by different people.

On international projects, keep in mind that translations are not always as clear as one would expect. Additionally, even if the project language of choice is English, team members may interact with people whose primary language is not English.

In all virtual communications, keep in mind that the message conveyed must be consistent (Garrett 2007), and you should attempt to communicate that message in several different ways, such as by email, phone, or face-to-face interaction—to reinforce the message, action items, and deadlines.

People’s Behavior

When communication is inconsistent or lacking, oftentimes the involved parties will behave in a manner that is inconsistent with the expectations placed on them. If expectations are confusing, individuals will modify their actions based on what they believe to be the expectations. It is common for people to move towards easier guidelines or to behave in a manner that is more aligned with their own agenda than with the goals and objectives of the project. If they believe they have a choice, most people will choose the easier road and follow their own preferences. These are not always incongruent with the goals of the project, if the organization has strong values, but it will certainly not be the most efficient path to project success.

Haste

Haste often leads to undesirable results. Rushing to meet a deadline has a way of increasing the number of mistakes, reducing quality, and causing rework. The pressure to complete a project on time or to attain certain milestones can cause individuals to disregard safety, policy, or procedures in order to achieve the expected goal (Garrett 2007). The pressures of haste can often lead to dangerous situations that can impact a project, or in extreme cases, an entire company or industry. Consider BP’s haste to reach an oil deposit with the Deepwater Horizon. Safety and other protocols were ignored in order to strike oil as fast as possible. Haste, in this case, resulted in the death of 11 people and led to the worst environmental disaster in recent history.

Think about this situation when you are in a hurry on a project. If a virtual project manager feels pressured by an encroaching deadline to cut corners, she should consider how haste could result in a very negative situation for the virtual project management office. If someone has barely enough time to finish the tasks at hand, that person will have little time to communicate his or her status to others. This loss of communication time can seriously impact a project if stakeholders have to turn to less reliable, secondary sources for information.

Deception

Whenever money changes hands, there is the possibility that one party will attempt to deceive another for potential gain. Intentional treachery may be to blame, but deception is usually not intentional; sometimes it is a result of a misunderstanding of the requirements of the project. For example, new system implementations most commonly fail because the system provider unintentionally deceived the client. The supplier believed its solution would fit the client’s needs, but it became apparent during implementation that the system was never capable of achieving the client’s requirements (Garrett 2007).

Note that communication risk is not limited to generally risky or complex projects. It’s important to understand risks associated with communication and work to identify and mitigate them, as risk reduction can increase an organization’s longevity, among other benefits. So how can a project manager do her part to reduce communication risk? She must learn to modify her behavior in the future. In the future, instead of firing off a quick email response, she should wait and consider a more careful answer that has definite closure as its goal. Specifically, the project manager should:

Consider the list of communication risks above when crafting the response (and any time she needs to communicate about a project).

Set a response time for the answer (consider waiting 24 hours).

Close by asking the recipient what he is doing to support the project. This encourages him to provide information instead of asking more questions. The recipient’s answers can be included in the next project update.

Forward these responses (or pass them along to the project historian) to other stakeholders as appropriate. They will show the stakeholders how others are supporting the project. Evidence of stakeholder support will generate more interest than basic updates on budget and schedule would. Showing how others are supporting the project demonstrates its positive effects.

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION

Once an organization is committed to developing or expanding its virtual project management organization, it must come to grips with the fact that moving forward, almost all of the organization’s communication will be done virtually. This does not mean that the organization should consider virtual communication to be the only form of communication, but it must understand that it will be the primary way people in the VPMO reach out to stakeholders. Some might see this as a hindrance to the organization, but a real understanding of virtual communication will allow the organization to leverage its strengths.

Virtual organizations must take advantage of online communication, which is more adaptive than people may realize. It offers a richness of information that was previously not believed to be possible. In the past, virtual organizations were limited to sharing information via simple text interfaces because of cost, bandwidth, and technology restrictions. Hence, online communication was brief, disjointed, and one-sided. Although technology has expanded to offer greater flexibility in communication, it appears that the typical means of communication continues to be the simple memo. Email has made memos easier to circulate, but, in the end, an email is still a type of memo.

In the past, hard-copy memos were the only manner of managing organizational degrees. Hard-copy memos would be handed out to the relevant people. If they had questions, they would walk down the hall to discuss the matter with others. Because a memo was static and might not provide answers for every possible scenario, it was only a piece of the communication relationship. In today’s virtual organization, people do not have same familiarity with one another, so most of the time, documents (usually electronic) must stand on their own. Few people in virtual organizations frequently reach out to discuss information they receive because they assume that it should need no further explanation.

Best practice: No memo ever changed the world. Even the Emancipation Proclamation, the document that forever freed slaves in the states that were in rebellion against the United States, did not change the world. It was the action of people after the document was signed that changed the world. Remember that memos are just pieces of paper; it is the actions of people that actually effect change.

A memo, or any piece of written communication, is composed of two primary elements: a degree of visuals and a degree of voice. The secondary element, which is often unrecognized, is the human interaction (HI) between individuals affected by the memo. In a traditional business environment, people can pass on information via visuals and voice (V&V) as well as through human interaction. The primary vehicle of information transfer in written communication is based on visuals (e.g., words, displays, charts). Visuals can be adapted to video or, in some cases, voice recordings.

The ratio of V&V and HI is not 50/50; it is driven by people’s individual communication style. Keep in mind that there are no requirements for the human interaction element; however, an organizational leader would be considered particularly ineffective if he or she did not allow people to ask questions regarding new processes, policies, or procedures.

There is no magic behind an effective memo or communication. Whether a communication effort works is based on how the material is presented and how well it is absorbed by the intended audience. On a virtual project, this will likely be done online. Technology and a little creativity can help you produce something more interesting and memorable than a static memo, such as videos or podcasts.

The human interaction element includes asking questions and answering them and solving problems. Interaction helps reinforce the message being presented. In a traditional organization, where all parties are available for an impromptu discussion or clarification, this can happen in person. HI is also possible in a virtual environment, and it is important, as it will improve the virtual communication process. Of course, HI needs to be enabled by technology on a virtual project, and sufficient training and support are needed to make virtual HI successful (Runyon 2010). If an organization is committed to regular virtual interaction, it must invest in technology, including video conferencing software or even a video studio.

Best practice: How people interact is often more important than the information that is exchanged. How can tone be used in virtual communication to enhance or clarify a message?

Best practice: Many people can talk for hours, so it is hard to believe that so many of them are actually poor communicators. In terms of communication style, people tend to be similar to birds. Birds sing to attract a mate, mark territory, or share information. Their songs are audible to a wide range of animals, including humans. The bird is unconcerned about who hears its song (if a bird was worried about predators, it certainly would not give its location away by singing). People, like birds, can broadcast information about their lives without always revealing their true feelings. People tend to hold back more information than animals. If a bird feels threatened, it will attack or flee. If a person feels threatened, he can attack, flee, panic, hide, or lie. This variety of reactions makes human communication difficult to understand.

Bees communicate in a substantially different manner. They cannot vocalize, so they must use a complex dance (and possibly scent) to communicate with their brethren. This kind of communication is very specific and substantive. The bee needs to make sure that the hive is aware of a food source or of potential danger lurking in the distance. Bees’ communication is never concealed, and their direct communication is important for the survival of the hive. Directed communication like this is the kind that is effective in a project environment.

Most communication in an organization is general and wholly unrelated to the project at hand. The minority of communication is actually productive. The key to effective communication on a project is getting people to spend a little more time communicating like a bee and less like a bird.

Communication must be an integral part of the VPMO. The organizational structure of the VPMO must allow for communications to flow to and from the VPMO and up and down the chain of command. The VPMO leaders should consider themselves advocates for all aspects of project management. To do this, they must be adept and effective oral and written communicators.

In a virtual world, the written word is sacrosanct, and the virtual project relies heavily on the written word. The VPMO can provide a valuable offering to the project community by helping the project teams communicate effectively. The VPMO should provide training on the different lines of communication, the implications of a relative lack of face-to-face communication, body language, culture, communicating with stakeholders in the virtual environment, and many other aspects of virtual project management.

The VPMO staff may also provide hints to the virtual project manager on ways to assess loneliness. Remember, by nature humans are social creatures. The virtual project manager has to make sure that team members don’t become isolated.