Framing a new agenda for semantic publishing

In 1686 Gottfried Leibniz finished the most comprehensive of his contributions to the field of logic, Generales Inquisitiones de Analysi Notionum et Veritatum, a work of formal logic focusing on the relationships between ‘things’ and ‘concepts’, truth and knowledge. His method was to develop a system of primitive concepts, to create compilations of tables of definitions, and to analyse complex concepts on the basis of a logical calculus. And his aim was to create an ‘alphabet of human thought’, using letters and numbers to denote concepts and to derive logical conclusions (Antognazza 2009, pp. 240–44). His intellectual ambition?:

[G]o back to the expression of thoughts through characters, this is my opinion: it will hardly be possible to end controversies and impose silence on sects, unless we recall complex arguments to simple calculations, [and] terms of vague and uncertain significance to determine characters… Once this has been done, when controversies will arise, there will be no need of a disputation between two philosophers than between two accountants. It will in fact suffice to take pen in hand, to sit at the abacus, and—having summoned, if one wishes, a friend—to say to another, ‘let us calculate’ (quoted in Antognazza 2009, p. 244).

Over three centuries later, we live in a modernity in which we pervasively rely on calculation, often now in the form of computable information. And we’re still debating the potentials of calculability. Leibniz may have been overly optimistic in his time, but are the aspirations to artificial intelligence and the semantic web still overly ambitious today? ‘When will we be able to build brains like ours?’, asks Terry Sejnowski, Francis Crick Professor at the Salk Institute in Scientific American. ‘Sooner than you think’ he replies, pointing to developments in computer and brain sciences (Sejnowski 2010). Pure fantasy, this is not going to happen anytime soon, replies John Hogan a couple of issues later (Horgan 2010). We still don’t know whether Leibniz’s aspiration for calculability can be realised.

The internet now constitutes a consolidated and widely accessible repository of a remarkable amount of human meaning. Yet, ‘computers have no reliable way to process the semantics’ of web content, lamented Berners-Lee, Hendler and Lassila in their seminal 2001 article introducing the semantic web. ‘In the near future’, they say, the semantic web ‘will usher in significant new functionality as machines become much better able to process and “understand” the data that they merely display at present’ (Berners-Lee, Hendler and Lassila 2001). A decade later, this promise was called Web 3.0 (Hendler 2010), but it remained little more than a promise. As we work over that now enormous body of represented human meanings which is the internet, we still have nothing much better than search algorithms which calculate statistical frequencies of character collocations, as if ‘set’ always meant the same thing every time the word is used.

The problem may be the extraordinary complexity of human meaning, as expressed in language, image, sound, gesture, tactile sensation and spatial configuration. The web may be able to record writing, sound and image, but our capacities to turn these into computable meanings is still limited. Meanwhile, the broader computer science agenda of artificial intelligence has become narrower as its results have proved disappointing. Hubert Dreyfus says that the roots of the problem are in the ‘rationalist vision’ of its research program, based on a ‘symbolic information-processing model of the mind’ and its incapacity to represent ‘the interests, feelings, motivations, and bodily capacities that go to make a human being’ (Dreyfus 1992, p. xi).

What then might be more modestly achievable in that peculiar discursive space, academic knowledge work?

The academic language game

Modern biological taxonomy orders life according to each lifeform’s evolutionary relationship to a predecessor. Species are groups of biological individuals that have evolved from a common ancestral group and which, over time, have separated from other groups that have also evolved from this ancestor. In the taxonomic hierarchy established by Linnaeus in the eighteenth century, a species (for instance, ‘sapiens’) is a member of a genus (homo—hence the formal, Latin naming scheme creates the term ‘homo sapiens’), a family (hominids), an order (primates), a class (mammals), a phylum (vertebrates) and a kingdom (animals). Living things are classified in this system in ways which, after careful application of definitional principle, are often contrary to commonsense. The everyday concept of ‘fish’ no longer works, since the systematic analysis of evolutionary variations in recent decades has shown that lungfish, salmon and cows all share a common ancestor, but lungfish and cows share a more recent common ancestor than lungfish and salmon (Yoon 2009, pp. 255–58). Commonsense semantics suggests that fish are more alike because they look alike and live in water. Careful semantic work, based on disciplinary definitions and principles, tells us something remarkably and revealingly different.

Creating systematic order is an old practice, as old at least as Aristotle’s categories and logic (Aristotle 350 BCE). Markus, however, points out an enormous difference between modern disciplinary knowledge and earlier forms of philosophical wisdom, integrally related as they were to the persona or habitus of the thinker. Modern knowledge becomes objectified and made widely accessible in the form of disciplinary schemata:

The idea of the system destroys this ‘personalistic’ understanding of the socially most esteemed form of knowledge which claimed to be an end in itself. It divorces philosophy—further regarded as a value in itself—from its direct impact upon the life of its practitioners (or recipients), from its personality-forming, illuminative influence, and thereby creates the conceptual preconditions within the framework of which the modern conception of the autonomy of cultural accomplishments first becomes intelligible (Markus 1995, p. 6).

In this view, the creation of disciplinary knowledge as an autonomous discursive space is a peculiar accomplishment of modernity which requires the development of shared schematic and discursive understandings.

In the founding moments of philosophical modernity, Kant speaks of an ‘architectonic’ or an ‘art of constructing systems’. On the one hand, this is an a priori way of seeing: ‘the idea requires for its realisation a schema, that is, a constituent manifold and an order of its parts’. On the other hand the process of construction of schemata is at times circuitous:

only after we have spent much time in the collection of materials in somewhat random fashion at the suggestion of an idea lying hidden in our minds, and after we have, indeed, over a long period assembled the materials in a merely technical manner, does it first become possible for us to discern the idea in a clearer light, and to devise a whole architectonically in accordance with the ends of reason (Kant [1781] 1933, pp. 653–55).

In this tradition, the early Wittgenstein attributes these schematic qualities to language itself, positing the world as an assemblage of facts nameable in language, alongside a propositional facility which ties those facts together (Wittgenstein [1922] 1981). In other words, he attributes to natural language an intrinsic logic of categories and schematic architectonics. The later Wittgenstein claims that natural language works in much more slippery, equivocal ways.

Schematic conceptualisation becomes the stuff of ‘ontology’ in the world of the semantic web, as if such representations are unmediated or true expressions of empirical ‘being’. As Bowker and Starr point out using as their case studies the disease classifications used on death certificates and the system of racial classification that was apartheid in South Africa, schemata do not unproblematically represent the world ‘out there’. They also reflect ‘the organizational context of their application and the political and social roots of that context’ (Bowker and Star 2000, p. 61). How objective are the categories when much their definitional purport is contestable? And despite their promised regularities, they are fraught with irregularities in data entry—what ‘goes’ in which category? How does the context of application affect their meanings in practice? ‘We need a richer vocabulary than that of standardization or formalization with which to characterize the heterogeneity and processual nature of information ecologies’, they conclude (Bowker and Star 2000, p. 293).

The later Wittgenstein developed perspectives on language which were very different in their emphases from his earlier work. Meanings do not simply fit into categories. Apples and tomatoes are both fruit, but apples are more typically regarded as fruit than tomatoes. To this semantic phenomenon, Wittgenstein attached the concept ‘family resemblance’ as an alternative instead of strict definitional categorisation, a graded view of meanings where some things more or less conform to a meaning expressed in language. And instead of a world of relatively unmediated representational meanings, Wittgenstein proposed a world of ‘language games… to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life’ (Wittgenstein 1958, pp. 2–16). Something that means one thing in one text or context may—subtly or unsubtly—mean something quite different in another. As meanings are infinitely variable, we can do no better than pin specific meanings to situation-specific contexts.

Recently, Gunther Kress has argued—and we have argued similarly in the work on ‘multiliteracies’ we have undertaken with him and others (Cope and Kalantzis 2000, 2009)—that language is not a set of fixed, stable and replicable meanings. Rather, it is a dynamic process of ‘design’. We have available to us ‘resources for representation’—the Designed. These resources

are constantly remade; never willfully, arbitrarily, anarchically but precisely, in line with what I need, in response to some demand, some ‘prompt’ now—whether in conversation, in writing, in silent engagement with some framed aspect of the world, or in inner debate (Kress 2009).

This is the stuff of Designing. And the consequence is a trace left in the universe of meaning in the form of the Designed, something that in turn becomes an Available Design in a new cycle of representational work. These, then, are Kress’s principles of sign making: ‘(1) that signs are motivated conjunctions of form and meaning; (2) that conjunction is based on the interest of the sign-maker; (3) using culturally available resources’. The design process is contextually specific, dynamic and no two signs mean precisely the same thing:

Even the most ordinary social encounter is never entirely predictable; it is always new in some way, however slight, so that the ‘accommodations’ produced in any encounter are always new in some way. They project social possibilities and potentials which differ, even if slightly, from what there had been before the encounter. As a consequence, the semiotic work of interaction is always socially productive, projecting and proposing possibilities of social and semiotic forms, entities and processes which reorient, refocus, and ‘go beyond’, by extending and transforming what there was before the interaction… It is work which leads to semiotic entities which are always new, innovative, creative; not because of the genius of the participants in the interaction but because of the very characteristic forms of these interactions, in which one conception of the world—the ‘ground’ expressing the interest of one participant—is met by the different interest of the interlocutor (Kress 2009).

These things are true to the slipperiness of all language, and particularly so in the case of vernacular, natural language. In disciplinary work, however, we create a strategically unnatural semantics to reduce the contextual equivocations and representational fluidity of natural language. Disciplinary work argues about meanings in order to sharpen semantics—in discussions of what we are really observing, to define where one category of thing ends and other begins, to clarify meanings by inference and reasoning. These are peculiar kinds of semantic work, directing focused semantic attention to provisionally agreed meanings in a certain discipline. The peculiar insightfulness and efficacy of this semantic work is that it helps us do medicine, law, philosophy or geography in some relevant respects better than we could with mere commonsense expressed in natural language.

Of course, semantic slipperiness and fluid representational design is true of academic work, and even productively so when it becomes a source of generative dissonance and innovation. Our point here is the strategic semantic de-naturalisation in disciplinary work, the relative ‘automomy’ (to use Markus’) word of disciplines from individual voice, and the comparative ‘objectivity’ of disciplinary discourses as communally constructed artefacts.

However, the prevailing temper of our times does not sit well with formal semantic systems. The postmodern language turn follows the later Wittgenstein into a realm of meanings which trend towards ineffability, and infinitely varied meanings depending for their semantics on the play of the identity of the communicator in relation to the ‘role of the reader’ (Barthes 1981; Eco 1981).

Disciplinarity, or the reason why strategically unnatural language is sometimes powerfully perceptive

The semantic web in the formal sense is the system of web markup practices that constitute RDF/OWL. This system, however, may prove just as disappointing as the results produced thus far by computer scientists working on artificial intelligence. It may bear as little fruit as earlier modern aspirations to create systems of calculable meaning on the basis of formal logic. The reason lies in part in the infinitely extensible complexity of human meaning, into which natural language analyses provide just one insight.

This book has suggested an approach to meaning which has the modest objective of doing a somewhat better job than search algorithms based on character collocations. Where the semantic web has thus far failed to work, we want to suggest a less ambitious agenda for ‘semantic publishing’. By this, we mean the active construction of texts with two layers of meaning, the meaning in the text (the conventional stuff of representation in written words, pictures and sound) and, layered over that, a markup framework designed for the computability of the text whose effect is to afford more intelligent machine-mediated readings of those texts.

Academic knowledge is an ideal place to start to develop such an agenda. From here, the agenda may spread into other spaces in the web, in the same way that the idea of backward linking which weights search results in the Google algorithm derives from the idea invented half a century earlier by Eugene Garfield, the idea that citation counts could serve as a measure of intellectual impact.

Natural language is not readily computable because of its messy ambiguities, its context-variable meanings, and the vagaries of interest in which often dissonant nuances of meaning are loaded into the roles of meaning-makers and the different kinds of people in their audience. If language is itself semantically and syntactically endless in its complexity, then on top of that the infinite variety in contexts of expression and reception multiplies infinite complexity with infinite complexity. None of this complexity goes away in academic work. However, such work at times sets out to reduce—at least in part—the contextual slipperiness and semantic ambiguities of natural language. This is the one aspect of the practice of intellectual ‘discipline’.

To define our terms and reflect on our context, an academic discipline is a distinctive way of making knowledge a field of deep and detailed content information, a community of professional practice, a form of discourse (of fine semantic distinction and precise technicality), an area of work (such as an academic department or a research field), a domain of publication and public communication, a site of learning where apprentices are inducted into a disciplinary mode, a method of reading and analysing the world, an epistemic frame or way of thinking, and even a way of acting and type of person. ‘Discipline’ delineates the boundaries of intellectual community, the distinctive practices and methodologies of a particular area of rigorous and concentrated intellectual effort, and a frame of reference with which to interpret the world.

Wherever disciplinary practices are to be found, they involve a kind of knowing that is different from the immersive, contextually embedded knowing that happens pervasively and informally in everyday life. Discplinarity deploys a kind of systematicity that does not exist in casual experience. Husserl draws the distinction between ‘lifeworld’ experience and what is in ‘transcendental’ about ‘science’ (Cope and Kalantzis 2000; Husserl 1970). The ‘lifeworld’ is everyday lived experience. It is a place where one’s commonsense understandings and actions seem to work instinctively—not too much conscious or reflective thought is required. It is a place where the ambiguities of and ineffable complexities of natural language at once enlighten insiders and confound strangers. Knowledge in and of the lifeworld is amorphous, haphazard and tacit. It is relatively unorganised, acquired by accretion in incidental, accidental and roundabout ways. It is endogenous, embedded in the lifeworld to the extent at times that its premises and implications are often all but invisible. It is organic, contextual, situational.

The ‘transcendental’ of disciplinary knowledge is, by comparison, a place above and beyond the commonsense assumptions of the lifeworld. In counterdistinction to the relative unconscious, unreflexive knowledge in and of the lifeworld, science sets out to comprehend and create epistemic designs which are beyond and beneath the everyday, amorphous pragmatics of the lifeworld. Disciplinary knowledge work is focused, systematic, premeditated, reflective, purposeful, disciplined and open to scrutiny by a community of experts. It is deliberate and deliberative—conscious, systematic and the subject of explicit discussion. It is structured and goal oriented, and so relatively efficient in its knowledge work. It is exophoric—for and about the ‘outside world’. It is analytical—abstracting and generalising to create supra-contextual, transferable knowledge. It is sufficiently explicit to be able to speak above and beyond the situation of its initial use, to learners and to other disciplinarians, perhaps in distant places or adjacent disciplines. All in all, disciplinary practice is more work and harder work than the knowing in and of the lifeworld.

The disciplinary artefacts of academic work are the result of deliberate knowledge design work, special efforts put into knowing. This work entails a peculiar intensity of focus and specific knowledge-making techniques, working at the interface of everyday life and specially designed efforts to elicit deeper knowledge. Disciplinary work consists of things people do that make their understanding more reliable than casual lifeworld experience. To become critically knowledgeable about phenomena of the embodied lifeworld, and in ways of knowing beyond taken-for-granted experience, requires systematic observation; the application of strategies for checking, questioning and verification; immersion in the culture of the way of knowing under examination; and the use of multiple sources of information.

More rigorous knowledge-making strategies include corroborating perceptions with others who have seen the same thing and which can be further tested and verified by others; applying insight and awareness based on broad experience that moderates emotions and feelings; justifying opinions and beliefs to oneself and others, including those whose judgement is to be respected based on their expertise; taking into account ideologies which represent interests broader than one’s own and with a longer view than immediate gratification; taking into account statements whose logical consistency can be demonstrated; developing perspectives based on long, deep and broad experience and which are broadly applicable; grounding principles in critical reflection by oneself and others; and forming intelligence in the light of wary scepticism and an honest recognition of one’s own motives. The knowledge that is founded on these kinds of knowledge-making practices and purposeful designs for engagement in and with the world help form a person who may be regarded as knowledgeable, a person who has puts a particularly focused effort into some aspects of their knowing.

Knowledge worthy of its name consists of a number of different kinds of action, which produce deeper, broader, more trustworthy, more insightful and more useful results. We have to concentrate on our ways of knowing to achieve this greater depth or expertise. We have to work purposefully, systematically and more imaginatively at it. What, then, do we do which means that our knowledge transcends the everyday understandings of the lifeworld?

Knowledge processes

Disciplinary work consists of a number of knowledge processes. It is not simply a process of thinking or a process of understanding in the cognitive sense. Rather it is a series of performatives—acts of intervention as well as acts of representation, deeds as well as thoughts, types of practice as well as forms of contemplation, designs of knowledge action and engagement in practice as well as concept. The deeper and broader knowledge that is the result of disciplinary work consists of the kinds of things we do (knowledge abilities) to create out of the ordinary knowledge. Fazal Rizvi calls the practices entailed in creating reliable knowledge ‘epistemic virtues’ (Rizvi 2007).

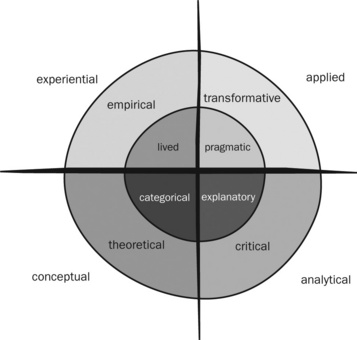

Figure 15.1 shows a schema of four-by-two knowledge processes.

Experiential knowledge processes

Disciplinary practice has a basis in lived experience. Some of this may be bound up in the peculiar disciplinary and discursive practices of a field of endeavour (Cetina 1999; Latour and Woolgar 1986). In other respects it is bound up in personal experience, social background and socio-ethical commitments. In other words, the personal and professional profile of the person informs a certain kind of rhetorical stance (Bazerman 1988). In a work of academic representation this is noted explicitly in credits attributing institutional location and role, and biographical notation that sits alongside the text. The knowledge does not simply speak for itself. Its interlocutor needs to be trusted. And, more subtly, the experiential identity aspect of an authorial agenda is also to be found in the rhetorical structure of the text.

Disciplinary work may also have an empirical basis, either directly in the reporting of observations, facts and data or indirectly reporting on already published empirical material. Empirical work involves the experience of moving into new and potentially strange terrains, deploying the processes of methodical observation, carefully regulated experimentation and systematic reading of experience. This involves refined processes of testing, recording, measurement, quantification and description. In the documentation of empirical data, clear coding and markup according to established and agreed disciplinary categories will facilitate more effective data mining. In some disciplines, the test of veracity is replicability, which requires clear documentation of empirical methods.

Conceptual knowledge processes

Academic disciplines use categorical frames of reference based on higher levels of semantic distinction, consistency and agreement within a community of expert practice more than is commonly the case in natural language. Here, we may make knowledge by grouping like and unlike on the basis of underlying attributes, and we may abstract, classify and build taxonomies (Vygotsky 1962). This kind of knowledge work includes defining terms, refining semantic distinctions and classifying empirical facts. This is what makes the language of the disciplines unnatural by comparison with the casual ambiguity of vernacular natural language. In the domain of digital text making, this is the space where specialist tags, dictionaries and glossaries are made.

Disciplines put concepts to work in theories that model the world and build explanatory paradigms. Theoretical work builds conceptual schemas capable of generalising from the particular, abstracting from the concrete and explaining processes whose workings may not be immediately obvious. Theory making involves building conceptual schemes, developing mental models, and conceiving and representing systems. It becomes the basis for the interpretative frames that constitute paradigms, and a reference point for confirmation or distinction of new work in relation to the generalisations that have hitherto been agreed. In the world of digital markup, this is the stuff of taxonomic and other concept-to-concept relationships.

Analytical knowledge processes

Disciplinary work involves developing frames of reasoning and explanation: logic, inference, prediction, hypothesis, induction and deduction. As a knowledge process, this involves making sense of patterns, analysing conceptual relations, and developing rules or laws which reflect regularities and systematic reasoning. In the world of markup, this is the stuff of conceptual dependency relations.

Disciplinary work also often analyses the world through the always cautious eye of critique, interrogating interests, motives and ethics that may motivate knowledge claims. It promotes, in other words, an ever-vigilant process of meta-cognitive reflection. This is represented in documentation via discussion of points of empirical, theoretical and ethical distinction of new work from earlier works.

Applied knowledge processes

Disciplinary work is also application-oriented, either directly or indirectly in the case of basic research. It is pragmatic, designing and implementing practical solutions within larger frames of reference and achieving technical and instrumental outcomes. What purpose knowing, after all, other than to have an effect on the world, directly or in the case of basic research, indirectly? This kind of knowledge process involves practical forms of understanding and knowledge application in a predictable way in an appropriate setting. In terms of markup practices, its referrents of application might include time, place, industry or social sector—in which case it might be possible to come back at various times after initial publication to review the intellectual work against the measure of the text at the sites of its application.

In its most transformative moments applied disciplinary work is inventive and innovative—redesigning paradigms, and transforming social being and the conditions of the natural world. This kind of knowledge process may be manifest as creativity, innovation, knowledge transfer into a distant setting, risk taking, self-enablement, and the attempt to translate emancipatory and utopian agendas into practical realities. Among the measures of the impact of the work may be markup by other users of the sources of ideas, schemas and practices.

Some disciplines may prioritise one or more of these acts of knowing, these disciplinary moves, over others. In any event, these are the kinds of things we do in order to know in the out of the ordinary way of academic disciplines. Each step of the way, disciplinary work involves kinds of semantic precision which constitute a phenomenon we would like to call ‘strategically unnatural language’. The dimensions of this unnaturalness become an agenda for semantic publishing.

Towards a new agenda for semantic publishing

The ‘semantic web’ conceived as a series of formalisms at the intersections of XML, RDF and OWL has not thus far worked, and postmodern sensibility may have forewarned the inevitability of its failure. However, if the semantic web has failed to realise its promise, rudimentary semantic publishing practices are in evidence everywhere.

For instance, semantic tagging has notably sprung to prominence in the world of the digital media. Soon after the appearance of the social bookmarking website Del.icio.us in 2004, the tagging practices of users came to be observed and commented on. Thomas Vander Wal called this practice ‘folk taxonomy’ or ‘folksonomy’—in the case of Del.icio.us, tagging was designed to assist classification and discovery of bookmarks. David Weiberger characterised the difference between taxonomy and folksonomy as akin to the difference between trees and fallen leaves: ‘The old way creates a tree. The new rakes leaves together’ (Wichowski 2009).

If there is anything particularly semantic about the web today (beyond the text itself), it is this unstructured self-tagging practice. However, this practice has severely limited value as a support for online knowledge ecologies. At best, folksonomy is a flat world of semantic ‘family resemblances’. Tags are quirkily personal. They mix terms which have semantic precision in disciplines with vague terms from natural language. They give no preference to disciplinary expertise over commonsense impressions. They have no dictionary or thesauri to specify what a person tagging really means by the tag they have applied. Tags are not related to tags. And to the extent that tag clouds add some grading of emphasis to the tags they represent, they simply provide a measure of lowest common denominator tag popularity, mostly highlighting the tediously obvious. Might folksonomy be just another moment of postmodern epistemic and discursive angst? Must we succumb to the anti-schematic zeitgeist?

We need schematic form, but with the rigidities of traditional taxonomy and logical formalism tempered by flexible and necessarily infinitely extensible social dialogue about meanings. We have attempted to create this in the infrastructure we described in Chapter 13, ‘Creating an interlanguage of the social web’. Here, for now and by way of conclusion to this book, are our guiding principles, each of which corresponds to the ‘knowledge process’ ideas we introduced in the previous section of this chapter.

The principle of situated meaning

Disciplinary meanings are situated in communities of disciplinary practice. In this respect, there is more to knowledge than contingent language games (Markus 1986, pp 17–18) and the endlessness of variations in representational voice and reception. In fact, the struggle to agree on a strategically unnatural language entails ongoing debates to minimise these ever-present semantic contingencies. Communities of disciplinary practice are constantly involved in the critique of commonsense misconceptions (what you might have thought ‘fish’ to be) or ideological spin (on sources of climate change, for instance). This is not to say that individual members or even whole communities of disciplinarians are necessarily exempt from blindsighting by conventional wisdom or ideological occlusion. But the discursive work they do aims to refine meanings in order progressively to add perspicacity to their knowledge representations and extend them incrementally.

However, our digital knowledge infrastructures today do not provide disciplinarians with formal knowledge-representation spaces with which to refine the computable semantics of their domain. Static and ostensibly objective schemas are at times available—ChemML might be an archetypical case—but these do not have an organic and dynamic presence in the communities of intellectual practice they serve. They are not in this sense sufficiently situated. Operationally, they reflect a legacy of centralised and hierarchical knowledge systems, which needs to be opened out to the whole discipline.

Moreover, they need to be situated in another sense. Unlike Wikipedia, the authorial positions of people involved in the tag definition and schema formulation dialogue need to be made explicit in relation to the work they have done—the paradigm they represent, the empirical investigations they have done, the specific area in the subdiscipline. Suchman draws an important distinction between representationalism and situated action, the former purporting to represent the world in relatively unmediated ways (for instance, in our example, received ‘ontologies’—the word itself is revealing), the latter constituting ‘the cumulative durability of force and practices and artifacts extended through repeated citation and in situ re-enactment… It is only through their everyday enactment and reiteration that institutions are reproduced and rules of conduct realized’ (Suchman 2007, pp. 15–16). Scollon recommends a focus on chains of mediated action (Scollon 2000, p. 20), in which terms, the discursive practices of schema formation need to be embedded in disciplinary work and an integral part of the chains of action characteristic of each discipline. Our informatic infrastructures must be built to support this (inter)action, rather than impose semantic rigidities.

The conceptual-definitional principle

If the situated is to extend its meanings beyond its sites of experiential depature, if our chain of mediated disciplinary action is to produce a body of knowledge autonomous of individuals and accessible to all, we need to provide our disciplinary communities with the tools for introducing concepts, defining their scope and exemplifying their contents. Rather than flat tags whose meanings are taken as given, disciplinarians need to be given spaces to add concepts, define concepts and exemplify them. Brandom calls this a process of ‘making beliefs explicit’, in which ‘the objectivity of representational content is a feature of the practices of assessing the correctness of representations’ consisting of a series of practices of giving and asking for reasons… and justifying beliefs and claims’ (Brandom 1994, pp. 78, 89, 639). This is how dialogue is established about the relationships of concept to purported referrent.

The analytical principle

Then there is the question of relations of concept to concept. Deacon, following Pierce, speaks of two axes of meaning. The first is iconic and indexical representation, where signifier more or less reliably correlates with signified. Animals can do this. What is remarkable and unique about the words of human languages is that

they are incorporated into quite specific individual relationships with all the other words in the language… We do not lose the indexical associations of words… [Rather we have a] sort of dual reference, to objects and other words… captured in the classic distinction between sense and reference. Words point to objects (reference) and words point to other words (sense)… This referential relationship between words—words systematically indicating other words—forms a system of higher-order relationships… Symbolic reference derives from the combinatorial possibilities (Deacon 1997, pp. 82–83).

Academic work takes this symbol-to-symbol work to levels of analytical delicacy and precision not found in natural language. This is one of the things we need to work on in communities of disciplinary practice, whether in the rhetorical flow of academic writing or in the schemas that also embody dependency relations. We need the simple dependencies implicit in taxonomies (parent, child and sibling concepts), and much more.

The transformational principle

Not only do we need schema infrastructures that push their markups out to the world; we need ways in which the world can speak back to these markups. Every markup is a documented instance of its concept. At every point the instance can throw into question the concept. Schemata must be designed not just to apply, but to allow that the application can speak back. Every concept and every concept-to-concept dependency is open for debate in every moment of tagging. Each tag is not simply a ‘this is’ statement. It is also an ‘is this?’ question. In this way, schemata remain always open to transformation—incrementally or even paradigmatically.

References

Antognazza, M.R. Leibniz: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Aristotle. ‘Categories’. The Internet Classics Archive. 350 BCE http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/categories.html, 2010. [(accessed 22 July].

Barthes, R. Theory of the Text. In: Young R., ed. Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1981:31–47.

Bazerman, C. Shaping Written Knowledge: The Genre and Activity of the Experimental Article in Science. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1988.

Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J., Lassila, O. The Semantic Web. Scientific American; 2001. [May].

Bowker, G.C., Star, S.L. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000.

Brandom, R. Making it Explicit: Reasoning, Representing and Discursive Commitment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994.

Cetina, K.K. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999.

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. London: Routledge; 2000.

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M. “Multiliteracies”: New Literacies, New Learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal. 2009; 4:164–195.

Deacon, T.W. The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: W.W. Norton; 1997.

Dreyfus, H.L. What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1992.

Eco, U. The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. London: Hutchinson; 1981.

Hendler, J., Web 3.0: The Dawn of Semantic Search. 2010. [Computer, January].

Horgan, J. Artificial Brains are Imminent… Not!. Scientific American; 2010.

Husserl, E. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston: Northwestern University Press; 1970.

Kant, I. [1781]Smith N.K., ed. Critique of Pure Reason. London: Macmillan, 1933. [(tr.)].

Kress, G. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge; 2009.

Latour, B., Woolgar, S. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1986.

Markus, G. Language and Production: A Critique of the Paradigms. Dordrecht: D. Reidel; 1986.

Markus, G. After the “System”: Philosophy in the Age of the Sciences. In: Gavroglu K., Stachel J., Wartofsky M.W., eds. Science, Politics, and Social Practice: Essays on Marxism and Science, Philosophy of Culture and the Social Sciences. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1995:139–159.

Rizvi, F. Internationalization of Curriculum: A Critical Perspective. In: Hayden M., Levy D., Thomson J., eds. Handbook of International Education. London: Sage, 2007.

Scollon, R. Action and Text: Toward an Integrated Understanding of the Place of Text in Social (Inter)action. In: Wodak R., Meyer M., eds. Methods in Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage, 2000.

Sejnowski, T. When Will We Be Able to Build Brains Like Ours?. Scientific American; 2010.

Suchman, L. Human-Machine Reconfigurations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Vygotsky, L. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1962.

Wichowski, A. Survival of the Fittest Tag: Folksonomies, Findability, and the Evolution of Information Organization. First Monday. 14, 2009.

Wittgenstein, L. [1922]. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Routledge: London, 1981.

Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations. New York: Macmillan; 1958.

Yoon, C.K. Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science. New York: W.W. Norton; 2009.