Chapter 8

Getting Results: Transfer of Learning

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Discovering how to follow up with your participants

Discovering how to follow up with your participants

![]() Overcoming barriers to transfer of learning

Overcoming barriers to transfer of learning

![]() Recognizing the importance of planning for transfer

Recognizing the importance of planning for transfer

![]() Finding out what great trainers do after training

Finding out what great trainers do after training

“Well, that was a great training session; now back to work!” Have you ever heard a colleague say something like that upon returning from a training session? I have left training with a big binder filled with good ideas. But because work piled up while I was away on a training session, I’ve placed that binder on my desk, promising myself that I would look at it later and implement what I learned. Later came and went, and soon I moved the binder to a shelf next to lots of other binders filled with good ideas. Why does this happen? And when you’re the one in the training role, is that what you want to occur? Of course not! It takes a team effort to ensure that learning transfers to the workplace.

The supervisors, learners, and trainers form a team right from the start to ensure that learning and skills transfer from the training session to the workplace. The pre-training and post-training activities are as critical as the actual training itself, so to ensure transfer of learning and performance, you need to plan for them all. Follow-up actions are useful, to be certain. Just remember that even though transfer of learning occurs after the training session, it must start before the delivery of training, whether the classroom is virtual or physical.

This chapter focuses on both your role as a trainer and your expanded role as a talent development professional. I address the barriers to transfer of learning and the importance of planning for the transfer. I also offer suggestions and tips for what virtual and face-to-face trainers do following a training session.

Making Your Training Memorable: Follow-Up for the Other 50 Percent

An issue cited by trainers since the beginning of time is that the concepts learned in the classroom may not transfer to the job. The training experience becomes a void — an isolated experience that has no practical application in the real world. Some professionals call the follow-up that’s required “the other 50 percent.”

So what’s the “other 50 percent”? You need to look at the entire system from an organizational perspective. The reason that learning does not transfer could be organizational (policies, negative consequences), lack of management support, or the lack of required equipment, supplies, or support system for the learner. Therefore, it may not have been a training problem in the first place.

However, assume that you conducted a great needs assessment and were correct in identifying a training problem, yet the training didn’t transfer. This section considers some barriers that may prevent an effective transfer of learning, as well as some steps that you as a trainer can take to overcome these barriers during the design phase.

Note: I could have placed this topic anywhere in the Training Cycle because transfer of learning starts with the needs assessment, to ensure that a training problem really exists, and it ends with implementation of the learning when the employee is back on the job. I’ve placed it in its own chapter to give it the emphasis it needs. However, because you know there is a need for follow-up at the design stage, be sure to build in strategies you need at that time — early in the process.

Recognizing barriers to transfer of learning

It’s unfortunate, but true: Many barriers exist that prevent learning from transferring to the job, such as the ones in this list:

- Changing behavior is difficult, so participants revert to old habits when back on the job.

- Participants may be the only ones practicing the new behavior, and peer pressure may cause them to reject the new learning.

- The participants’ supervisors may not understand the new knowledge, skills, or behaviors, so they don’t support or reinforce them.

- The participants’ supervisors may not agree with the new knowledge, skills, or behaviors, so they may undermine them.

- The participants’ supervisors may not be proper role models for the new knowledge, skills, or behaviors.

- The informal organizational culture may punish the new behavior. For example, I once worked with an organization that made coded locking systems. Their product’s return rate was increasing, and they found that the returned systems were defective because of production errors. Parts were missing and assembly was incorrect. Company decision makers thought that they needed to retrain all their assembly people, when in effect what they needed to do was to change their compensation system. Employees were paid by the number of systems they shipped on a daily basis, not by the quality of the final product. Not surprisingly, employees had the incentive to work as quickly as they could, as opposed to accurately.

Using strategies for transfer of learning

Even though the ability to overcome some barriers may be out of your hands, you can do your part as a trainer to ensure transfer of training. Although the transfer of training occurs after the actual session, this section presents what you can do before the training occurs, during the training session, and after the session. Use all these ideas for the best assurance of transfer of learning, whether you have a virtual or a face-to-face instructor-led training (ILT).

Pre-training strategies

Trainers can implement numerous strategies before the training even begins to ensure that training transfers to the workplace, such as one of these:

- Perform a needs assessment: As covered in Chapter 4, make sure that you’ve derived the training you provide from a well-conducted and analyzed needs assessment. Be certain that you’ve aligned the training with the organization’s strategic plan.

- Coach management: If managers have requested specific training for their employees, meet with the managers to gain specific information from them, as well as to let them know exactly what their roles will be in supporting and reinforcing the training. Encourage them to meet with the learners to help them know why attending this training is important. In some cases, you may want to give them a checklist of topics to cover with their employees, or even suggested questions.

- Inform managers about the training: Provide management briefings about the training. Inform them about how the training supports the organizational goals. Let these folks know the objectives, the expected outcomes, and the expected benefits. Alert management to any organizational barriers that may adversely affect the desired outcome. Engage the managers in problem solving through the barriers and get their commitment to support the group solution.

Provide pre-training projects: Get participants and their managers involved in the training concepts before the training begins. You can do this by having them complete instruments or surveys that will, in turn, be used as resource material or data in the actual training program.

For example, the supervisor interview is one of my favorite techniques. I create a list of four to six interview questions that are directly related to the content of the training session. I ask participants to interview their supervisors before coming to the session. When we reach specific topics in the session that are related to the interview questions, I ask participants to share their supervisors’ comments. Often the supervisor is as interested in how the information was used as the participant, which creates a good basis for discussion when the learners return to the workplace.

Training strategies — during the session

You can make use of numerous strategies during the session to ensure that training transfers to the workplace:

- Provide practical application: Make sure that every topic you cover in the training is job related and has a specific real-world application.

- Use actual examples: When conducting role plays, simulations, and other activities, use actual data and experiences. These can come from the interviews you have with managers or participants prior to the session.

- Build in plenty of practice opportunities: After you know the knowledge and skills required of the learners, design activities that include practice with feedback.

- Poll expectations: Before conducting the training program, poll the expectations of the participants to assure them that you’re providing them with the skills and information they need.

- Include transfer to the job in debriefings: When you debrief on any activity, make sure that one debriefing topic is a discussion of how participants can apply the lessons of the activity to their jobs.

- Encourage follow-up actions: Participants can fortify and augment what they learned by tapping into additional resources from a list that you can provide. They could plan to discuss with their bosses how they will implement what they learned.

- Create a reminder: Participants can note their primary goals on their tablets, laptops, smartphones, or other locations where they will see them often.

- Use a meeting invitation: Have participants send a meeting invitation to their supervisors to discuss what they learned and what they’d like to implement.

- Have peer transfer partners: They can be called many things: learning buddies, peer mentors, or learning partners, but the idea is to assign them before learners leave the training session. These partners connect on a weekly basis by email or phone to answer each other’s questions and to provide moral support. This has become one of my favorite tactics with virtual training.

- Create an action plan: After the training has been conducted, have participants list what they are going to do on the job as a result of training. Discuss participant ideas with the entire group.

In any virtual session — depending on the topic — I have participants share their planned action either in an email to me or a personal chat to me. In a month, I email each participant, include their action item, and offer my support.

Post-training strategies

Transitioning learners from “I tried it” to “I’ll apply it” requires facilitators to design follow-up activities and provide tools to both the learner and the supervisor. For learning to transfer, the participant must be committed to the change. In addition, the supervisor must provide the learner with support. As a trainer, you must support both the learner and the supervisor.

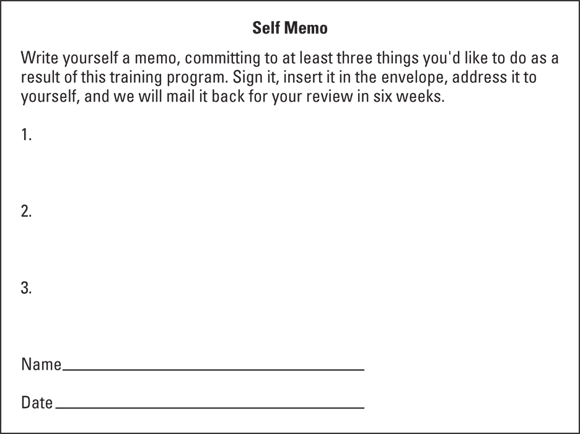

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 8-1: Self memo.

These suggestions identify strategies that you can use to ensure that learners apply what they learn:

- Follow up with letters, emails, or phone calls: A few weeks after the program is completed, you can write follow-up notes or make phone calls to remind participants of some of the concepts and ask how they’re doing in applying them. The phone call has the advantage of being interactive and allows participants to share barriers they’re encountering and get ideas from you about overcoming them. See the upcoming sidebar “Assisting learners with change.”

- Use mobile devices: Everyone has a smartphone or tablet to receive messages, so determine whether you can put learning into the palm of your participants’ hands. Follow up with concise tips and reminders to help your learners stay focused on implementing their new skills.

Share the follow-up: When you follow up with participants, track what you learn. If someone asks a practical question that wasn’t covered in the training, or if the same question comes up several times, take note. Share this information with everyone in the class via an email or a tweet, or on a class site that you have established for them.

You may want to credit one of the participants with follow-up: “Dan brought to my attention that we did not ________________.” This crediting will encourage others to bring these things to your attention.

You may want to credit one of the participants with follow-up: “Dan brought to my attention that we did not ________________.” This crediting will encourage others to bring these things to your attention.- Form support groups: As a trainer, you can encourage participants to form support groups. A small group of people can commit to meeting after a specified period of time to discuss how they have applied the learning, what problems they have encountered, and what they have done to overcome the problems. They may also prefer to form an online support group. I was recently invited to participate in a Zoom call with a group of participants in which lively discussion ensued.

Have a reunion: If support groups don’t appeal to the participants, you can call for a reunion and have participants demonstrate how they’re implementing what they learned in the workplace.

I’ve heard of some groups who were so dedicated to reconnecting with the other participants that they met after work.

I’ve heard of some groups who were so dedicated to reconnecting with the other participants that they met after work.- Enlist past participants as mentors: Match participants who have attended the training in the past with participants who have just completed the session. If at all possible, bring them into the classroom at some point during the session to meet each other.

- Play Twitter Tag: Before everyone leaves the session, obtain all participants’ Twitter usernames. Tweet a practical-but-new idea related to the topic to everyone. Name someone at the end as the “Twitter Tag, you’re it.” That person tweets something within 24 hours and names another person from the group. Try this as one of your activities during the session, too.

- Do a quick survey: Use a tool like SurveyMonkey to conduct a quick survey about how each learner is using the content in the workplace. Compile it and share it with all learners.

Use other feedback: Think about other ways to gather data about the success of the session. For example, if you taught a computer class, you can check the help desk calls immediately after the session to determine whether there are references to your session. If there are, it means that participants are trying the skills but still need assistance. Perhaps there is a better method to use next time.

Organize a collaboration tool for participants to share successes, ask questions, or just to stay in touch in general.

Organize a collaboration tool for participants to share successes, ask questions, or just to stay in touch in general.- Provide job aids: Job aids are short, written or electronic guides or check sheets that summarize the steps of a task or job procedure. They may also be performance support systems (PSS) or posters that can be taken back to the workplace. Job aids serve as reminders to the participants after the training has been completed. They are especially useful after a skill training program. However, job aids can also be effective in reminding participants of key behavioral concepts.

- Spread the news: Suggest that supervisors ask their employees to share what they learned with the rest of the department. This sharing could occur during a staff meeting, or time could be set aside just for the topic.

- Encourage management support and coaching: The best way to assure post-training application is to have participants’ managers provide support and coaching. You could provide a sheet of coaching tips to managers and then follow up to offer assistance to them in the coaching process.

- Meet with managers: Three to four weeks following the session, meet with the managers in person or on a call to determine whether the training addressed the needs and whether the employees are applying the skills and knowledge. You may also use this time to determine what other needs could be addressed in the future.

Doing What Great Trainers Do after Training

Many of the same strategies that you use with participants are things that you can do for yourself to ensure continuous improvement. For example, you can write yourself a memo, committing yourself to at least two things you’d like to do better as a result of facilitating your session. Sign it, insert it in an envelope, address it to yourself, and ask someone to mail it back for your review in a month. When it arrives, it can serve as a reminder of what you were supposed to have accomplished.

Make a habit of reviewing your training notes immediately after the session and make additions or changes while it’s all fresh in your mind.

Be sure to study the evaluations. What suggestions do the participants have for you? What can you do differently next time, based on the feedback? Review several sets of evaluations to identify any trends and the changes they may require on your part.

Follow up with the participants, sending them any materials that you promised to send. This is a great opportunity to find out how they’re doing and how you may be able to help them transfer the skills.

If you don’t have a Smile File, start one today. A Smile File is a place where you can keep all your kudos. If you did a great job facilitating, you’re sure to receive notes, emails, and cards complimenting you on something special or thanking you for going out of your way. Your Smile File will be useful when having a difficult day. Reading the wonderful things participants have said makes it all worthwhile.

These days, resiliency (individual and organizational) is on every leader’s mind. I recently shared a Resiliency Checklist with individual leaders from one organization, delivering them in person to offer additional support and receiving a very warm welcome. One manager was so appreciative that he started to tear up.

Understanding Your Talent Development Professional Role

As a talent development (TD) professional, you need to expand your thinking from training to serving a broader talent development role:

- From a trainer’s perspective, knowledge transfer refers to what individuals learn and how they implement it, transferring it to the job.

- From a TD professional’s perspective, knowledge transfer refers to how knowledge is shared, transferred, and implemented throughout the organization.

Knowledge transfer and sharing are critical for your organization now. Organizations have been operating in a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) area for many years, but not until the pandemic did every company realize how important knowledge transfer was. The only two words I heard more often than pivot during the pandemic are resilience and agility. Both words are key to an organization’s ability to ensure knowledge transfer, innovation, and success. Both relate to individuals in the company as well as the organization itself. When you have your TD professional hat on, what do those concepts mean for your organization’s ability to not just survive, but to thrive?

- Agility is an organization’s ability to rapidly evolve and adapt to meet the changes required for results.

- Resilience is an organization’s ability to anticipate and prepare for both incremental and disruptive change.

Both of these characteristics depend on your organization’s knowledge management. Knowledge is an organization’s intellectual capital. We live in a knowledge-driven economy, so knowledge becomes an organization’s asset, and the ability to transfer it throughout the organization makes it more valuable. Nancy Dixon, author of Common Knowledge: How Companies Thrive by Sharing What They Know (Harvard Business School Press), believes that knowledge is transferred in five ways:

- Expert transfer happens when an individual must seek the knowledge from an external expert.

- Strategic transfer occurs infrequently but is of critical importance to an organization’s intended future.

- Far transfer happens when individuals learn from doing nonroutine work and then transfer their learning to others.

- Near transfer occurs when an individual reuses knowledge from another team or individual based on repeated tasks.

- Serial transfer occurs when an individual immediately applies knowledge learned from one activity, such as training or coaching.

You might say that sounds great, but what are the actual methods that support knowledge transfer? Well, here’s where you come in. You know a lot more about it than you might think. You already have some of the knowledge transfer tools in your training toolbox, including simulations, storytelling, professional development, job aids, and role plays. Because you have the tools, you are prepared to implement the transfer of learning discussed in this chapter.

Some of you may have the next level of tools related to career development, such as job rotations, job shadowing, mentoring, coaching, and cross-department teamwork. A few others include after-action reviews, process documentation, communities of practice, and even just attending meetings.

Today’s fast-paced, knowledge-driven economy requires that organizations continue to innovate and adapt to be positioned to ensure that the right people have the right knowledge at the right time. As you can imagine, that catchy phrase is easier said than achieved.

Knowledge benefits an organization only if employees and teams are willing to capture, absorb, accept, and apply knowledge when it’s needed. Your organization can shape its culture to increase its institutional knowledge and ability to thrive.

Although short, this chapter contains concepts that are critical for all trainers to know. Transfer of learning and transfer of skills beyond the classroom are why you are in business. In this fast-moving world, it would be easier to “call it quits” at the end of the training session. But a great trainer makes sure to complete follow-up activities to ensure that transfer of learning has occurred.

As you leave this chapter, remember the words of one of the pioneers in the training profession, Robert Mager, who stated in his book Making Instruction Work (Center for Effective Performance, 1997): “If it’s worth teaching, it’s worth finding out whether the instruction was successful. If it wasn’t entirely successful, it’s worth finding out how to improve it.”

Training isn’t just for learning; training is for doing. That means you’re expected to make sure that the learning is transferred to the workplace.

Training isn’t just for learning; training is for doing. That means you’re expected to make sure that the learning is transferred to the workplace.