CHAPTER 1

Meet The New Corporate Facts of Life

It is not the strongest of the species that survives; nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.

—CHARLES DARWIN

FEW LOGOS ENJOY as much global recognition as the Nike Swoosh. You see it on people's clothes and shoes all over the world. But Bill Bowerman and Phil Knight, founders of the iconic Nike brand, never thought of themselves as mere apparel and footwear salesmen. It all started when Bowerman, a nationally recognized track-and-field coach at the University of Oregon, always searching for ways to improve the performance of his athletes, joined forces with one of his former runners to create and market better running shoes. One of the company's early innovations came from Mrs. Bowerman's waffle iron, which inspired a more effective design for the soles of high-performance footgear.

Like many of the companies you'll meet in this book, Nike constantly strives for excellence but cannot avoid its share of serious business problems. Corporations, after all, are only human (or, more accurately, collections of humans). In the late 1990s, Nike came under attack for some of its suppliers’ terrible labor practices. The press and the public condemned the unsafe working conditions, forced labor, and child employment involved in the manufacture of some products bearing the Nike Swoosh. When Nike did not swiftly move to address these issues, protesters burned Nike shoes, boycotted Nike products and demanded action. In 1998, the company's earnings dropped by a whopping 69 percent. Swoosh had obviously stepped into a quagmire.

While that experience didn't knock Nike off the track, it dramatically changed the rules of the game. Redefining its entire perspective on supply chain management, Nike moved to clean it up by training and auditing suppliers and choosing to do business only with those who adhere to fair and legal labor practices. But the campaign did not stop there. Nike moved beyond managing risk and rebuilding its brand, and assumed a leadership position, with the overriding goal of redefining every aspect of its business and thereby transforming an entire industry.

While the company aims to find new and better ways to serve its customers’ needs to grow and to make money, it does so under an overarching umbrella of sustainable growth through innovation. For instance, it uses its Flyknit technology to make lighter weight and more custom-fitted shoes. But the process accomplishes even more. By weaving the upper portion of a shoe with a single thread, the manufacturing process creates far less waste than conventional methods. Additionally, a waterless dyeing technology conserves a valuable resource by using CO2 rather than H2O to dye textiles. On a broader scale, Nike collaborates with NASA, the U.S. Department of State, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to encourage innovations for more socially and environmentally sustainable materials. The company also shares intellectual property for green product design, packaging, and manufacturing with competitors in order to help the entire industry operate more sustainably.

My research into Nike and scores of other forward-looking companies during the past several years has identified seven powerful, interconnected forces that will trigger a catalytic change in the global business landscape:

- Disruptive innovation

- Economic instability

- Societal upheaval

- Stakeholder power

- Environmental degradation

- Globalization

- Population shifts

These irresistible forces have created what I call The New Corporate Facts of Life (NCFOL). They cannot be ignored. Although the incremental changes of the past did not fundamentally alter the business terrain, and required relatively minor tactical adjustments, the ones emerging from this era of catalytic change demand a major shift in strategic thinking. We stand on a brink of changes every bit as massive as those that shaped the Industrial Revolution and the Information Age.

Like many of the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, Henry Ford's automobile provided more than horseless transportation; it launched an era of mass production and modern management techniques. It paved the way for a sprawling infrastructure of roads and fueling stations, and supported a vast array of new industries. And as it reshaped the landscape, a large percentage of the population shifted from an agricultural to an urban lifestyle. Likewise, the Information Age has irreversibly transformed everything we do, from buying and selling goods and services to accessing entertainment, knowledge, and social communication.

The NCFOL are also reshaping our world in powerful and irreversible ways. They demand that business leaders think deeply and ask questions about the future of their companies, such as how do we innovate in a world where our products and services can become obsolete overnight? What investment decisions must we make in the midst of global economic instability? How should we respond to the social upheaval rocking the world? How can we best serve our increasingly powerful stakeholders? What steps can we take to protect the environment from continued degradation and remain profitable? How can we enter emerging markets with the greatest rates of population growth and a burgeoning middle class? How should we operate in this highly interdependent global maket?

The NCFOL do not affect just the global business giants like Siemens; they cascade into every nook and cranny of every little entrepreneurial venture on every street corner in every country on earth. Ignore them at your peril. If you despair that they pose insurmountable problems that only others can solve, they will eventually undermine your future. Redefine them as opportunities, as Nike has done, and you will greatly improve the odds that your organization—be it a business, a government agency, a not-for-profit or community organization, or an educational institution—will thrive. Milton Friedman's well-known observation that “the business of business is business” has rapidly changed to a view that business cannot ignore the world in which it operates. The two are inextricably interconnected. One cannot thrive if the other suffers.

This book will present not only the case for embracing this new reality but also many practical models and tools that will help any organization seize and profit from all the opportunities this new reality creates.

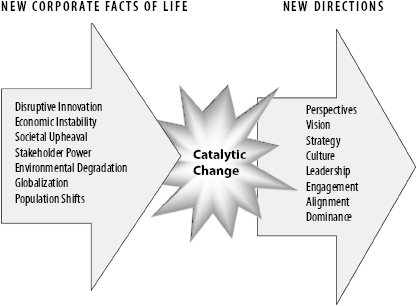

As Figure 1-1 illustrates, you can redefine key aspects of your enterprise by shifting your perspectives, redefining your vision and strategies, and executing your strategies through culture, leadership, engagement, and business model alignment to achieve and maintain dominance in your field.

In the chapters ahead, we will consider how the forces on the left may require rethinking the basic aspects of business on the right. For instance, when you think about your corporate culture, should you make some important changes in the light of disruptive innovation (“Does our current culture promote creative breakthroughs?”) and globalization (“Have we created a culture that transcends national boundaries?”)? At the end of each chapter, you will find The New Corporate Facts of Life Barometer, which will help you weigh the need for change in your organization. Although not every NCFOL will dramatically affect a given aspect of your business, you should still consider them all. The balance of this chapter will conduct a satellite's-eye tour of The New Corporate Facts of Life and both the challenges and opportunities they pose.

Figure 1-1. NCFOL Require New Business Directions.

Disruptive Innovation

Disruptive innovation occurs when a new product, service, or business model renders the old way of doing business obsolete. The Internet has disrupted everything from health care to shopping to dating. Telemedicine puts patient records on handheld devices and in the cloud, while smart grids redefine energy use. Personal computers bring instant information, interactive communication, productivity software, and endless entertainment to our desks and laps, while smartphones put it all in the palms of our hands.

Disruptive Innovation Economic Instability Societal Upheaval Stakeholder Power Environmental Degradation Globalization Population Shifts

The proliferation of cell phones provides an excellent case in point. A 2012 United Nations (UN) study reported that cell phones have been lifting more people out of poverty than any other innovation in history. The World Bank estimates that by 2012, approximately 75 percent of the world's population enjoyed access to cell phones, with 5 billion of the 6 billion mobile subscribers living in developing countries. Access to mobile communication advances human and economic development in so many ways—from paying bills, finding the lowest-priced products and services, and accessing health-care information, to keeping abreast of local, state, national, and international news, sharing information, joining protests, and pushing for more democratic processes.

Kenya has been leading the mobile wallet revolution since 2007. M-Pesa (M for mobile plus Pesa, the Swahili word for money) has created a mobile financial system that has transformed the lives and businesses of more than half the country's adult population. Launched as a joint venture between Vodaphone and Kenya's Safaricom, M-Pesa's mobile payment system allows Kenyans to transfer funds, pay bills, and eliminate the need for Masai herders to carry cash after selling their goods at the market. Cell phone technology goes beyond apps and gizmos; it promotes equality. Later in this book we'll see how innovations such as mobile devices contribute to other new corporate facts of life, including societal upheaval, stakeholder power, and globalization.

The 2012 GE Global Innovation Barometer survey of 1,000 global executives predicted that future innovations that address human need would eclipse those that merely generate high profit. The report does not urge company leaders to ignore the bottom line, but it does urge them to peer into the future, where shared-value innovations will increase access to health care, enhance wellness, improve the environment, spur job growth, promote energy security, and elevate education. Companies that seize those opportunities will reap the profits.

Challenges

Technology empires rise and fall quickly. In 2000, Microsoft owned the software universe, Apple languished as a niche player, Google had not yet evolved a business model, and the founder of Facebook had not yet graduated from high school. By 2012, RIM's Blackberry, once a disruptive innovation that married cell phone, Internet, and computer technologies into a handheld device, had lost most of its market share to other smartphones, especially to Apple's iPhone, and its stock had fallen by 93 percent. When digital photography replaced film, Eastman Kodak's business collapsed. Apple's iTunes transformed the music industry, and online travel sites all but eliminated travel agencies.

Opportunities

To keep up with such changes, companies must redefine how they foster innovation. The 2012 GE Global Innovation Barometer revealed that 88 percent of executives believe that the twenty-first-century approach to innovation will differ radically from yesterday's business-as-usual methods. The most forward-looking companies are adopting a new innovation model whereby they form and benefit from strategic alliances, tap into the creativity of individuals and smaller companies, and customize solutions to meet local needs.

Many have gone far beyond conventional corporate responsibility to create affordable solutions to major local problems in emerging economies. They do a world of good that not incidentally improves their bottom line. Unilever, for example, tackled the life-and-death problem of safe drinking water in developing countries and came up with a low-cost, high-quality solution, Pureit, a portable water-purifying device that makes water for drinking for less than half a cent per liter without using a single watt of electricity or existing tap water. Having launched the product in 2004, Unilever estimates that by early 2012 about 35 million people were using Pureit. With a tenfold growth forecast by 2020, Pureit will at that point become a multibillion-dollar business.

Even the least technological companies can create disruptive business models. Starbucks reinvented the coffee shop by turning their locations into ecofriendly gathering spaces with trendy design, Internet access, and their own music collections. Muhammad Yunus, a college professor in Bangladesh, launched global microfinancing through Grameen Bank by first helping local women start businesses funded with only a few dollars each. Zipcar and peer-to-peer car-sharing schemes, such as Spride Share, have disrupted traditional rental car companies by allowing people to rent vehicles by the hour through a network of screened renters.

Disruptive innovations range from the complex (developing a new computer operating system) to the simple (putting wheels on luggage). Although many companies launched during periods of economic prosperity, others sprouted despite adverse economic conditions. Apple, Microsoft, IBM, and Disney all came into the world during recessions.

All companies—not just those in the technology sector—face a daily onslaught of game-changing disruptive innovation. How do you stay on the leading edge of blindingly fast change? Courageous leaders choose to revolutionize the world, not just evolve with it. That means shifting your perspectives and rethinking the very design of your organization.

Economic Instability

Financial uncertainty threatens all countries, industries, and people. Our hyperconnected world links economies around the globe, in which events in even the tiniest countries impact the biggest ones. Industries in Thailand rely on industries in the United States. Small businesses in India depend on the success of global giants based in Germany. When a financial crisis strikes Europe, both private and public sectors must pull together to address the problem. What happens in Athens affects what happens on Wall Street. The business practices that took down Lehman Brothers and threatened the collapse of large institutions like AIG, Ford, and General Motors caused a tsunami-sized ripple affecting homeowners, merchants, and people in every imaginable job, from bricklayers to bankers, in every country from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Bailouts in the United States that helped save companies and jobs and thwarted a total economic collapse drove up the U.S. national debt, lowering its credit rating and threatening tax increases. The ripples flooded all the way to China.

In September 2012, Germany's top court voted to ratify and contribute to Europe's 700-billion-euro bailout fund. With that vote, Germany joined the 17-nation Eurozone behind the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) designed to throw a lifeline to Greece, Spain, and other troubled European Union (EU) countries. But German voters balked at that idea, endangering Prime Minister Angela Merkel's hold on government. The international community called for decisive and urgent leadership. Economic experts feared that Italy, the Eurozone's third largest economy, was too big to bail but too big to fail. Meanwhile, Greece's debt woes grew ever larger as Greece and Spain dealt with a 25 percent unemployment rate and France risked losing its wealthiest citizens in the wake of a threatened 75 percent income tax on the rich. The EU economic crisis fanned the flames of the global firestorm ignited by the 2008 financial meltdown.

Challenges

Businesspeople in the United States and other developed nations cry foul when manufacturing moves to China, India, and Bangladesh, yet those who object want affordable giant flat-screen TVs, iPads, and designer clothes. As wages in emerging nations such as China rise, manufacturers seek even cheaper labor elsewhere. However, a company must consider more than labor costs. The cost of transportation, import and export duties, maintaining a secure supply chain, shipping time, and fluctuating currency values also figure into manufacturing strategies. Many manufacturers now realize that it makes more sense to manufacture closer to the customers who buy their products. Companies such as Apple, Coleman, Caterpillar, Ford, GE, Whirlpool, and Toto recently onshored some of their manufacturing. The Boston Consulting Group's 2011 report, “Made in America, Again: Why Manufacturing Will Return to the U.S,” predicted that by 2015 many goods destined for North American consumers will bear “Made in the U.S.A” labels.

In addition, many firms have joined the recent trend of moving higher-skilled white-collar jobs to nearby countries where closer time zones help them better serve clients. Tata Consultancy Services Ltd., India's largest software exporter, and midsized competitor MindTree Ltd. have responded to tighter U.S. visa rules by hiring technology professionals in the United States to serve the needs of their clients there. France's Capgemini's global outsourcing operations capitalize on nearshoring by moving marketing, legal review, finance, and human resource services from the United States to Guatemala City and from Paris, Brussels, and London to Kraków, Poland. Capgemini's clients save up to 50 percent on labor costs while gaining access to college-educated staff who speak multiple languages with customer-friendly accents.

Economic instability swings both ways. Booming economic periods usher in their own challenges and opportunities. New businesses prosper and move from ramshackle garages to plush corporate buildings. Companies go global and expand into previously untapped markets. Launching your business in foreign countries may lower your production costs and reach new consumers, but not unless you navigate the landmines of politics, piracy, corruption, and cultural differences.

In boom times, technology companies drove up wages as they bid for high-tech workers, and the housing industry enjoyed skyrocketing home prices as banks extended loans to people who previously could not qualify. Builders erected new communities that needed new infrastructure to overcome the problems associated with jammed roadways, water shortages, and overcrowded schools. All of this proved unsustainable, however, and the bubble burst. People lost their jobs, much of their wealth, and most, if not all, of their retirement funds. As economies thrive, companies must manage growth while also creating contingency plans should new bubbles burst and threaten their very existence.

Opportunities

The period of economic decline that began in 2008 strongly affected consumerism as people bought less, demanded bargains, and searched the Internet for everything from used furniture to prescription drugs. Whole Foods Markets, an upscale pricey grocer for connoisseurs of organic food, introduced lower-price-point products and built smaller suburban stores to attract more middle-income customers. Walmart, once disdained by many as a poor shopper's paradise, attracted price-conscious customers who never would have set foot in their stores before 2008. People looking for online deals flocked to businesses like Groupon and Pinterest.

Today, many companies strive for ever greater efficiency to keep costs down. Companies such as UPS, Coca-Cola, and Novo Nordisk believe greater efficiencies today will enable them to remain profitable during tomorrow's inevitable difficult times and keep them positioned for long-term growth.

Other companies expand their presence in emerging and second-tier markets by offering low-cost products and services. Medtronic's Healthy Heart for All program brings pacemakers to hundreds of thousands of patients in India. Medtronic, the world's largest medical device manufacturer, set up rural camps with low-cost electrocardiogram (ECG) machines to send wirelessly transmitted ECGs to doctors hundreds of miles away. Relying on existing technology, the company's creative business model allowed it to enter new markets and position itself for expansion throughout the developing world.

Challenging economic times amplify societal challenges. Rising unemployment, increasing income inequities, escalating housing foreclosures, and expanding poverty and desperation plague cities and countries around the globe. A 2009 Boston University Report, “Beyond GDP: The Need for New Measures of Progress,” stressed the use of more complete measures of a country's well-being and progress to revise economic measures by, for example, adding so-called community capital indicators for ecological, social, human, and infrastructure progress. Doing so would give policy makers and society more complete data for making decisions by tracking whether a community is plundering its community capital rather than living off its interest.1 Companies such as Unilever, adidas, and BMW measure more than just economic value. They track resources saved, lives touched, and impacts on the communities they serve.

Societal Upheaval

Corruption, political unrest, poverty, food shortages, terrorism, pollution, unemployment, unfair labor practices, limited education, inadequate health care, and crimes against humanity erode the quality of life for people around the world. An oppressed and struggling population, armed only with smartphones, rises up to demand change. The resultant upheaval affects businesses far beyond that country's borders. Conventional corporate social responsibility, which often received more lip service than serious strategic investment, has become an imperative in today's turbulent world. Business leaders who fail to anticipate and manage societal issues make a big mistake because those issues can take down a company. Rather than ignoring societal upheaval, smart executives look for the opportunities hidden in all the noise of revolution.

In Tunisia, a 26-year-old fruit vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi protested government corruption and abuse and his village's 30 percent unemployment rate by drenching himself in paint thinner and setting himself ablaze in front of the governor's high gate. News of this December 17, 2010, event rapidly spread throughout the Arab world and beyond. Tunisian revolutionaries, employing a new arsenal of social media weapons, drove Zine-el-Abidine, the country's 23-year dictator, into exile and ignited what became known as the Arab Spring, as uprisings spread to Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, Libya, and Iran. Frustrated people around the world, including disaffected young Americans who flocked to the Occupy movement to protest societal and economic equality, continued to rise up and demand change. In 2011, the self-proclaimed “99%” launched the Occupy Wall Street movement that spread to other cities, where hundreds of thousands protested corporate greed and inequity and the perceived excessive influence of corporations on government. Even people in the richest countries on the planet suffer the effects of homelessness, crime, limited education, racial and gender prejudice, illegal immigration, and teen pregnancy, to name but a few social ills. Businesses cannot ignore such problems. Whether you sell products in the Middle East or Middle America, you operate in the context of a society. If that context becomes hostile or creates dangerous conditions, the effects can cascade all the way to your bottom line.

Challenges

Companies must navigate social, cultural, and political landmines both at home and abroad. When a company fully appreciates both the power and responsibility of its brand, it will address social issues to protect and positively enhance its image. They do not pay lip service to responsibility; they act on it. They police their supply chains for abuse of workers, unethical and illegal practices, and improperly acquired and processed raw materials. They strive for greater traceability of raw materials and transparency of business practices. When it became clear that the sale of illegal minerals from the Congo used in some smartphones and computers finance terrorism, the U.S. Congress passed the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, which required companies to disclose and crack down on their use of Congolese “conflict minerals.” Armed groups have used minerals such as tin, tantalum, gold, and tungsten (used by manufacturers in everything from smartphones to jewelry) to finance horrendous humanitarian atrocities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) region. In 2012, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission began requiring companies to disclose their use of conflict minerals originating in the DRC or adjoining countries.

More than 1,100 garment workers died and hundreds more suffered serious injuries in the 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh. Three weeks later, clothing makers around the world joined together to create a legally binding agreement to improve safety and working conditions for Bangladeshi factories in their supply chains. More than 70 apparel companies signed the agreement, including H & M, Zara, Abercrombie & Fitch, and PVH (parent company of such brands as Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein). The agreement's five-year commitment calls for independent, publicly reported safety inspections and provides financing for factories to improve safety. Several NGOs backed the agreement, including IndustriALL Global Union and UNI Global Union, which represent workers in 140 countries.

Opportunities

Strategically minded companies can find solutions to social issues that spur business growth and strengthen brand recognition. Water, women, and well-being offered just such an opportunity to Coca-Cola. The company's 5by20 initiative aimed to improve the economic well-being of 5 million women around the world by the year 2020. For instance, the company sets up manual distribution centers, many run by women in nations lacking transportation infrastructure, such as Kenya and Indonesia. Everyone wins. The company successfully enters new markets, and people in the communities gain income from new jobs.

In one case, Rosemary Njeri's distribution business in Kenya expanded from a small enterprise to become the second largest of the 37 centers supported by Coca-Cola in Nairobi. The company trained Rosemary to do required bookkeeping, manage inventory, and apply the necessary technology, and the local Coca-Cola bottling partner provided equipment and signage. Rosemary's business went from two employees to 16, including several members of her family. She has also started a support group of women distributors who meet regularly to discuss and find solutions for the business issues they face. Through efforts such as this, Coca-Cola gains respect for its brand with the message that “every bottle has a story.”

Other food and beverage companies fight obesity and increase revenues by offering healthier products. In the United States, the beverage industry voluntarily replaced high-calorie soft drinks with healthier options in schools. Several large corporations within the industry banded together in 2006 to form the Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative to encourage food and beverage companies to advertise healthier food to children. In the first year, McDonald's, Burger King, Kraft, Mars, and eight other companies pledged their commitment.

Partnering with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—once the height of business heresy—has enabled many companies to benefit both society and their business. When the Clinton Global Initiative began its AIDS initiative in 2002, only 230,000 people in developing nations were receiving medications. As of 2012, that number had grown to 8 million, due in large part to partnerships with pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline. By moving from a high-margin, low-volume to a high-volume, low-margin strategy, these companies bring lifesaving aid to people around the world while improving their profitability.

Addressing a major catalytic change and striving to discover and fulfill unmet needs goes beyond the old ideas of philanthropy and corporate responsibility. Smart, values-driven companies strive to devise innovative and profitable solutions that will simultaneously benefit people and boost the bottom line. All it takes is a new perspective, one that links a company's strategy to a radically new future.

Stakeholder Power

Since the dawn of the public corporation, business leaders focused primarily on their board members and shareholders as their key stakeholders. Yet doing so can lead to unintended consequences. Devout fans of Ben & Jerry's ice cream who admired the company's social conscience still mourn the day in 2000 when Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield sold their business to Unilever and the Ben & Jerry's brand became a sister to Vaseline, Slim-Fast, Ponds, and I Can't Believe It's Not Butter. In a 2008 interview, Jerry Greenfield told Hannah Pool of The Guardian, “We did not want to sell the business; it was a very difficult time. But we were a public company, and the board of directors’ primary responsibility is the interest of the shareholders. So that is what the decision came down to. It was extremely difficult, heart-wrenching.” The buyer didn't matter as long as it paid top dollar. Bottom line: The board and the needs of the shareholders ruled.

Some companies have opted to change their status to become “Benefit Corporations,” legal entities that must create a “material positive impact on society and the environment and to meet higher standards of accountability and transparency.”2 One Benefit Corporation, Patagonia, embraces a mission it calls The Change We Seek®, which mandates that the company “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”

Regardless of their legal status, companies must pay equal attention to an expanded universe of people who touch and who are touched by their organization: employees, customers, competitors, suppliers, community leaders and citizens, governments, NGOs, and alliance partners. When they involve all stakeholders, companies can reap the benefits of greater collaboration, innovation, loyalty, and awareness of both challenges and opportunities. Ignoring stakeholders can lead to a tarnished brand image, higher costs, disaffected suppliers, more frequent employee turnover, increasingly dissatisfied customers, and combative governments, communities, and NGOs.

More than ever, companies must reach outside the confines of their own operations to embrace all of their stakeholders. Although they must honor their legal obligations to put the interests of shareholders first, those interests increasingly benefit from positive relationships with all stakeholders. Profits and value now depend on attracting and retaining the most talented workers, enhancing the well-being of communities, creating respectful partnerships with suppliers, thrilling customers with more than a great product and a responsive customer care center, cooperating with regulators, and collaborating with domestic and foreign governments.

It takes but one small spark to ignite a forest fire. In 2011, Molly Katchpole, 22, a nanny living in Washington, D.C., was working two jobs and living from paycheck to paycheck when Bank of America announced that it would start charging her a $5 fee for making even one debit card purchase per month. Irate, Molly broadcast her displeasure on the Internet and started a petition on Change.org. To her surprise, she gathered 306,000 signatures from other folks fed up with big banks squeezing money from working people.

Around the same time, art dealer Kristen Christian vented her outrage with arrogant bankers on Facebook and encouraged her friends to stop doing business with the big banks.3 Kristen's messages ultimately spawned the November 5, 2011, Bank Transfer Day, when 610,000 people switched from big banks to smaller banks and credit unions. When the targets of consumer wrath, including Citigroup and Bank of America, called in police and security guards to manage the throngs withdrawing their money, they only reinforced their image as care-nothing bullies. Videos of skirmishes with protesters went viral on the Web. Although 610,000 may not seem like an overwhelming number, given the millions of Americans with bank accounts, a Javelin survey reported that 1,456,000 customers cited bank fees as the reason for transferring from big banks in the 90 days following Bank Transfer Day. Bank of America, reeling from pressure from the media, Congress, customers, and Change.org, agreed to drop the fee.

Challenges

Like Molly Katchpole and Kristen Christian, anyone can use smartphones, social media, and the Internet to become a global advocate and citizen journalist. Companies must continuously scan vast sources of information from The New York Times to YouTube and Twitter to see who loves and hates them. Potential employees can check out prospective employers on www.glassdoor.com, where people post comments on management and the work environment much as they would a hotel or book review. Advocacy groups target large companies, calling for more ethical business practices and greater responsibility in products, operations, supply chains, and more humane treatment of workers. NGOs harness technology to globally rally people around local environmental and social concerns.

Opportunities

Fully engaged employees bring their best efforts and creative ideas to work. A GreenBiz 2012 article, “Sustainability-Engaged Employees More Satisfied, Study Shows,” shared the story of Jeslin Jacob, a recent business school graduate disturbed by the fiberglass waste that her employer, a roofing company, was sending to landfills. After receiving a lukewarm response to her concerns from senior leaders, she took the initiative to create a market for fiberglass dust that not only diverted waste from landfills but also saved the company thousands of dollars a year. Jacob said, “I feel like I've left an invisible green signature on the products we make. And the more products we sell, the greater the impact of the project. Now that is a great incentive for me to grow business and that makes every day at work satisfying.”

Engaging suppliers can also yield far greater results than merely monitoring them. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable procurement bring increased emphasis to supply chain management. Companies shifting from a top-down to a collaborative approach to suppliers find ways to operate more efficiently and responsibly throughout the supply chain. Ford Motor Company trains suppliers and works with them on ways they can support the company's sustainable agenda. Companies such as Coca-Cola and Siemens AG recognize and reward suppliers for innovation and performance in helping them achieve and exceed CSR goals. InterfaceFLOR works with suppliers to develop new production processes and reduce costs and to increase profit margins for both their company and their suppliers.

Collaborating with NGOs turns former adversaries into so-called critical friends. At one time, such organizations as Gap, Swiss Re, and the International Timber Trade Organization viewed cooperation with NGOs as sleeping with the enemy. Now they partner with them to improve their products, solve supply chain problems, and operate more responsibly. In 2006, the Levi Strauss Foundation partnered with Business for Social Responsibility to launch HER-Project, a woman's health education program, in factories in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, and Pakistan. Five years later, the program, which focuses on improving women's health and helping factory workers connect to nearby health-care services, had aided more than 90,000 women in 65 facilities. One study found that for every dollar a company invests in factory health clinics, health education, and wellness training, it reaps $3 in increased productivity on the factory floor.

Environmental Degradation

A World Wildlife Fund 2012 report stated that at our current rate we are using 50 percent more resources than the earth can ultimately provide. If developing nations were to match the U.S. rate of consumption, humanity's needs would require 3.6 more planets. The old model that humans can plunder the earth at will and suffer no consequences has become obsolete. Environmental degradation brings drought, floods, unclean water, disease, death, security threats, and pollution. This sad state of affairs should concern corporations every bit as much as it does environmental activists. Negative perceptions of a company's impact on the environment decrease brand value; positive perceptions increase it.

Companies such as Sara Lee that source agricultural products in countries around the world face the problem of food shortages caused by climate change and severe weather conditions in various regions. Australia offers a dramatic case in point. The Deniliquin mill, the largest rice mill in the Southern Hemisphere, once processed enough grain to meet the needs of 20 million people around the world. But six years of drought reduced Australia's rice crop by 98 percent and led to the mill's closing in 2007. In a 2008 New York Times article, Ben Fargher, the chief executive of the National Farmers’ Federation in Australia, said, “Climate change is potentially the biggest risk to Australian agriculture.” The collapse of Australia's rice production contributed to a doubling of rice prices in early 2008, an increase that led to stringent export restrictions, panicked hoarding in the Philippines and Hong Kong, and violent protests in Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Haiti, Indonesia, Italy, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, the Philippines, Thailand, Uzbekistan, and Yemen.

Companies such as Toyota, Natura Cosmeticos, and Lockheed Martin have already heeded the threats posed by environmental degradation and have chosen to travel the path toward sustainable, profitable growth. The 2011 Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) by Standard & Poor 500 reported that 91 percent of the S&P 500 publicly discloses greenhouse gas emissions. It makes good business sense because these companies report that a 60 percent emission reduction project will pay for itself in three years or less. As with the other New Corporate Facts of Life, smart companies can convert the threats into opportunities. Not only will the planet and its inhabitants benefit from corporate efforts to protect the environment, but the companies themselves will profit from new sources of energy, less extreme weather events, the approval of investors, enhanced revenues and profits, and more innovative products.

One prominent U.K. retailer, Marks & Spencer (M&S), redefined retail for the twenty-first century. Robert Swannell, the company's chairman, views sustainable business development (environmentally, socially, and economically responsible growth) not as a corporate responsibility program but as a fundamental business factor. With revenues of £9.7 billion ($15.7 billion) in fiscal year 2010–2011, the company attributed £70 million of its profits to sustainability initiatives. M&S calls this approach Plan A. They've created no Plan B because they do not believe in doing business any other way. Adhering to Plan A, M&S works with customers and suppliers to maintain seven pillars: involve our customers, make Plan A how we do business, climate change, waste, natural resources, fair partner, and health and well-being. Between 2006 and 2011, M&S kept growing while reducing total carbon emissions by 13 percent, recycling 94 percent of its waste, and generating 54 percent of its energy from renewable sources. It obtains 90 percent of its wild fish and 76 percent of its wood from environmentally sustainable sources, and its stores now sell energy in addition to clothing and food.

Challenges

Greenpeace's 2011 “Dirty Laundry” report exposed the fact that China's footwear and apparel industry discharges 805 tons of industrial waste every second and that clothes manufactured there often contain toxic, hormone-disrupting chemicals. To prompt change, the advocacy group invited the two largest sports apparel companies, Nike and adidas, to compete in a Detox Challenge to publicly commit to eliminate all hazardous chemicals from their supply chains and products by 2020. Activists and supporters registered their support online and appeared on streets in front of Nike and adidas stores in 29 cities around the world on July 23 at exactly 11:00 a.m. Central European Time, not to picket (that's so 1990s) but to perform a choreographed striptease. Videos (many not appropriate for family viewing) spread across the Internet and attracted coverage by mainstream media and the blogosphere. While Nike and adidas pondered a response, PUMA, third in the industry, made the first commitment. Nike and adidas soon followed. Although the three companies did not know exactly how they could honor their pledge, they knew they needed to come together with others in the apparel industry to find solutions.

Several months later, leading apparel and footwear companies, Nike, adidas, C&A, PUMA, H&M, and Li Ning, announced the creation of a Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals (ZDHC) Programme to eliminate hazardous chemicals over the life cycle of apparel and footwear products by 2020. Through its Joint Roadmap, ZDHC members have set forth a new standard for the apparel and footwear industry, with specific commitments and timelines. Goals include educating suppliers, eliminating certain chemicals from the production process, developing transparent stakeholder engagement programs, and monitoring and publicly disclosing results. Other apparel companies, including Levi Strauss, Jack Wolfskin, Marks & Spencer, and G-Star Raw, signed the Joint Roadmap. As of June 2013, ZDHC participants made measurable progress by setting up seven workstreams, among them training, assessment and auditing, and initiating a chemicals management best practice pilot. Each workstream pursues specific 2015 milestone targets that they hope to achieve by 2020.

Companies must not only protect their brand image; they must stay ahead of increasingly complex regulations both at home and abroad. For example, American automakers began creating lighter, more efficient cars like the Chevy Volt and the Ford Fusion to prepare for 2025 U.S. regulations that will require an average fuel efficiency of 54.5 miles per gallon. When the European Union's 2006 Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive (RoHS) and the 2005 Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) directive emerged, smart companies standardized their global operations. Complying with regulatory requirements in each country, state, or city often means a company must manage sourcing, production, and logistics differently in various regions and play catch-up when tougher regulations arise. Companies such as HP and Cisco opt to go beyond the minimum requirements of each country by applying a so-called gold standard to activities throughout the world. Doing so helps them meet or exceed the highest standards while increasing efficiency and staying ahead of competitors.

Each year we experience severe weather conditions like Hurricane Sandy, the 2012 frankenstorm that devastated areas of the Caribbean and the mid-Atlantic and northeastern United States and that adversely affected the southeastern and midwestern states and eastern Canada. Sandy not only killed people and destroyed homes, it slowed energy production, strangled supply chains, and created a ripple effect throughout the entire U.S. economy. A year earlier, the March 2011 Japanese tsunami changed the course of nuclear power expansion worldwide after the nuclear meltdown and release of radioactive materials from the Fukushima I Power Plant. By January 2012, 19 countries had shut down 138 civilian nuclear power reactors, including 28 in the United States, 27 in the United Kingdom, 27 in Germany, 12 in France, and 9 in Japan.

Some companies do not sit around waiting for NGOs, governments, or weather conditions to force changes in their business practices. Instead, they become the force for change. In 2005, Walmart placed sustainability center stage when then CEO Lee Scott presented his vision for twenty-first century leadership. Viewing sustainability as the biggest strategic driver for the next 40–50 years, the company set long-term goals: operating with 100 percent renewable energy, achieving zero waste, and selling products that protect the welfare of people and the environment. Walmart's new requirements for packaging, transportation, plastics, toxins, water use, agriculture, and more sent eco-shock waves throughout their massive global supply chain.

Opportunities

To dispel the myth that going green costs more and hurts the bottom line, business leaders like Coca-Cola Enterprise's CEO John Brock promote the fact that managing resources brings savings, efficiency, and a positive return on investment. Brock points out that most of the company's environmental projects, such as lowering water and energy use and increasing recycling, quickly pay for themselves and enable the company to reinvest in its business and sustainability efforts.

The investment world now respects sustainable investing and impact investing. A 2012 MIT Sloan Management Review report, “Sustainability Nears a Tipping Point,” reveals that institutional investors such as pension plans and universities increasingly seek companies that not only make a profit but also adhere to high standards of social and environmental responsibility. Forward-looking investors like companies that compete for a spot on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) because they will most likely outpace less stable, less efficient, and less innovative competitors over the long run. Said Roberta Bowman, SVP and CSO of Duke Energy, “In addition to the more traditional ‘socially responsible investors’ we are finding that some of our mainstream investors are now looking at sustainability performance as an indicator of overall business value.”

Globalization

“It's a small world” is a saying that once denoted a coincidence; now it has become a reality. Globalization has created hyperconnected markets where communications technology and rapid transportation link citizens of the world together as never before. Just as information, ideas, talent, products and services, and investments travel the globe, so too do problems stemming from overpopulation, resource depletion, and income disparity. Peace and stability will provide the best solutions not just for individuals and governments, but for the world's business enterprises.

Most global issues defy easy solutions. When a 1993 NBC broadcast exposed child labor abuses in Bangladesh, highlighting a factory that supplied Walmart and other apparel companies, pending U.S. legislation threatened to close the American market to Bangladeshi garments if another case of child labor became public. In response, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association reportedly dismissed thousands of children from garment factories. Unfortunately, this action drove the victims into more dangerous work, such as welding and even prostitution. In contrast, when Levi Strauss faced a similar situation in Bangladesh, it allowed the children of factory workers to leave their jobs and attend school without losing wages and benefits. Jobs would await them when they reached legal age.

Starbucks’ strategy to implement sustainable, globally recognizable, locally relevant design sparks innovation and boosts brand loyalty. Works by local artists decorate café walls; school children paint murals for the burlap wall coverings; cement floors remain bare in a SOHO Oregon store; and local green providers supply handcrafted furnishings. In Paris, repurposed wine barrels decorate a Starbucks storefront, with retired champagne bottle racks adorning the interior. Considering itself in “the moment of connection business,” Starbucks seeks ways to connect with each local community across 55 countries while promoting its own global commitment to responsible growth. Starbucks serves the world and makes money one community, one store, and one cup at a time.

Challenges

Global supply chains have become increasingly complex and visible. Companies like Starbucks must consider growing conditions, agricultural practices, their effect on trees and wildlife, labor conditions, and worker housing in countries far from its Seattle base. One watchdog, The Rainforest Alliance, requires a company to meet more than 100 criteria in order to receive sustainable agriculture certification. That certification enhances a company's brand value.

Companies must shield their workers in other countries from violence and navigate a minefield of unfamiliar cultural and ethical mores. When developed nations went into an economic free fall in 2008, many businesses ramped up their strategies to enter emerging markets such as Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, and China, where local companies routinely pay bribes to get business done. This puts ethically minded multinationals at a distinct disadvantage and in a precarious position. Pressure to make up for declining revenues lured some executives to resort to bribery in order to remove obstacles and speed growth. When Siemens and Walmart did so, they found themselves embroiled in international scandals. A 2012 Harvard Business Review article, “Greased Palms, Giant Headaches,” reported that bribery and corruption rank a close second to competition and antitrust violations as the most frequent crimes committed by Western companies in emerging markets.”4

Opportunities

Companies will increasingly tap into emerging markets for growth. As of 2012, Proctor & Gamble reached consumers in 180 countries, Emirates Airline flew to more than 70, and McDonald's sold hamburgers in 119. Globalization often serves as a positive force. Consider how China has liftd 400 million people out of extreme poverty by opening their borders to trade.

Although many people think innovation starts in the richest nations and trickles down to the poorest, some companies tap the power of reverse innovation, where customers in the developing world adopt the newfangled first. A 2012 Ivey Business Journal article reported that when U.S.-based Deere & Company decided to produce a new tractor for use in India, it used a zero-based model to design it from scratch and not rely on Deere's current technology. Deere also involved local people on the design team to ensure that the result would match their needs. This approach enabled Deere to enter a new, expanding market with attractive lower-cost models.

Population Shifts

The expanding global population and shifting demographics change the game for all organizations. The UN has declared population growth the biggest problem of the new century, posing serious threats to human health, socioeconomic development, and the environment. The world's population grew from 2 billion in 1927 to 6 billion in 1998 to 7 billion in 2011, with the UN projecting that it will explode to 9.2 billion by 2050. Most of this growth will occur in the poorest countries. Today, 4 billion people, more than half of the world's population, survives on less than $2.50 a day. Pressure from this group, referred to as the Base of the Pyramid, pushes toward the top of society like a volcano about to erupt. A 2012 KPMG report predicted that by 2030 threats to food security due to population growth and related issues of water scarcity and deforestation could escalate global food prices from 70 to 90 percent.

Challenges

The more people on the planet, the more stuff they need, from petroleum products to cucumbers. This puts tremendous pressure on finite resources. The KPMG report also predicted that by 2030, the global demand for freshwater will exceed supply by 40 percent, threatening businesses with water shortages, lower water quality, price volatility, and erosion of their brand image for the wasteful use of water. Water-scarce areas will face the greatest challenges as growers compete for water with consumers and water-intensive industries such as mining and energy. Declining air quality also poses a threat to business. China's average passenger vehicle growth rate of 25 percent from 2000 to 2011 took the country from 10 million to 73 million vehicles. At the end of 2012, approximately 1 billion vehicles careened down the world's roads.

In another game-changing development, more than half of the earth's population now lives in cities. Siemens reports the world's 10 megacities account for 2 percent of the planet's population and a staggering 20 percent of global gross domestic product. City infrastructures cannot keep pace with the explosion. According to Siemens’ Sustainable Cities data, in 2010, 82 percent of Americans lived in cities; by 2050 the number will escalate to 90 percent. Cities now account for two-thirds of worldwide energy consumption, 60 percent of water use, and 70 percent of all greenhouse gases. Experts believe China's urban population will reach one billion by 2030. This increase in city dwellers would match the total population of the U.S. Urbanization, driven by economic development, increases consumption and demand for services. While this presents an opportunity for business, it also requires China to shift its emphasis from exports to meeting internal needs, from production to service, and from insensitivity to responsibility with respect to the environment.

A new generation of young people demand change. Mr. Land's students at Sun Valley Elementary School on Happy Lane in San Rafael, California (their real names) have challenged corporate giant Crayola to recycle the 500 million plastic markers the company produces each year. The students’ online petition generated 60,000 signatures the first month alone. “I think it really matters,” said fifth-grader Olivia McCabe. “We live on Earth and if we hurt it, there's no other place we can go to.”5

Opportunities

Companies find new consumers by selling to those at the Base of the Pyramid. The more than 900 million mobile phone users in India can buy a SIM card for about 20 cents and pay only 1 cent per minute. This low-cost, high-volume model creates a market for products and services ranging from banking and sandals to health care and government assistance. In 2010, an estimated 2 billion emerging middle-class consumers in a dozen countries spent $6.9 trillion. McKinsey's 2010 research indicates that this amount will rocket to $20 trillion by 2020, which equates to double the 2010 U.S. consumption. Luxury goods have also trickled into emerging nations. Prada opened its first store in China in 1993, joined by other high-priced designers Gucci, Armani, and Louis Vuitton. In 2012, 22 percent of Prada's revenue came from China and other emerging markets.

The challenges of urbanization bring opportunities for sustainable development. Siemens, General Electric, and Cisco view urbanization as an opportunity to upgrade aging infrastructures to more environmentally friendly ones that improve quality of life and reduce costs through energy and resource efficiency. As rural areas shrink and demand for food increases, solutions that emphasize greater agricultural productivity will come from companies such as farm equipment maker Deere and fertilizer makers Agrium and Potash.

Companies today manage employees spanning four or five generations. Having grown up in the digital age, the Millennials and members of Generation Y expect instant connectivity and gratification through their mobile devices. Far from the old world of nine-to-five glued-to-your-desk employment, this new generation merges their work and personal time, requiring employers to rethink performance review and reward systems, technology support, use of social media, working hours, workspace, and telecommuting. Recent college graduates with a strong social conscience seek responsible employers. As G.P. (Bud) Peterson, President of the Georgia Institute of Technology, told me, “Our students are incredibly intelligent; they want to change the world, and they are convinced they are going to do just that.”

Applying The New Corporate Facts of Life

Birds do it, bees do it, even business leaders do it. They obey the facts of life. The New Corporate Facts of Life will not go away. These are not flavor-of-the-month fads. They will increasingly determine whether your business strategies succeed or fail. Population growth fattens demand for natural resources while reducing their supply. Environmental degradation threatens the very survival of employees and customers. A rival's innovation renders everything you do obsolete. Access to technology connects folks from Aberdeen to Zambia and enables both brand-enhancing praise and damning criticism. Stakeholders become citizen journalists, creating viral blogs and videos that can make or break a brand. One smartphone can start a revolution. Economic uncertainty makes every investment an agonizing and possibly lethal decision. Globalization connects us all through economic fluctuations, fuel shortages, disease, security, commerce, and human rights.

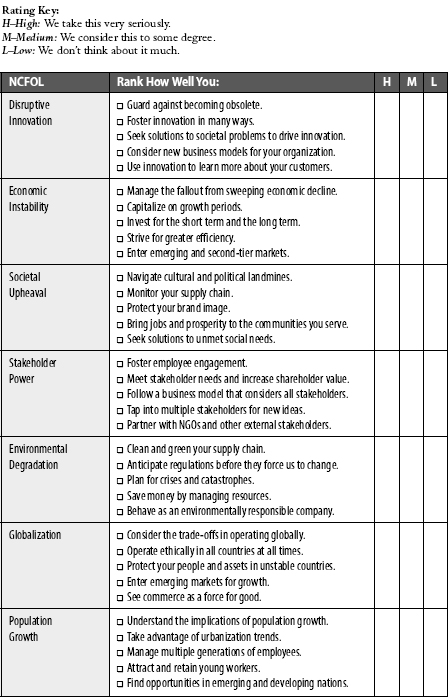

Every time you make a business decision, whether large or small, local or global, strategic or cultural, you should consider its implications with respect to The New Corporate Facts of Life. Here and at the end of each chapter in this book you can formalize such a review with The New Corporate Facts of Life (NCFOL) Barometer (Figure 1-2). Doing so will help you more deeply understand the issues surrounding the decision, the challenges it poses, and the opportunities it offers. Use it yourself. Invite other organizational leaders and cross-functional groups of people at all levels to try their hands at it. Involving a diverse range of internal and external stakeholders of different ages, experience levels, areas of expertise, and perspectives will raise possibilities that you yourself might miss.

After thinking about all this, do you see areas where you should improve your efforts? Which areas will most dramatically affect your business now and in the future? Who else should you engage in discussions of these trends? What areas should you research more thoroughly? Try to convert your answers into a redefined vision and strategic plan for this year, the next five years, and even the next 10 years.

Figure 1-2. The New Corporate Facts of Life Barometer.