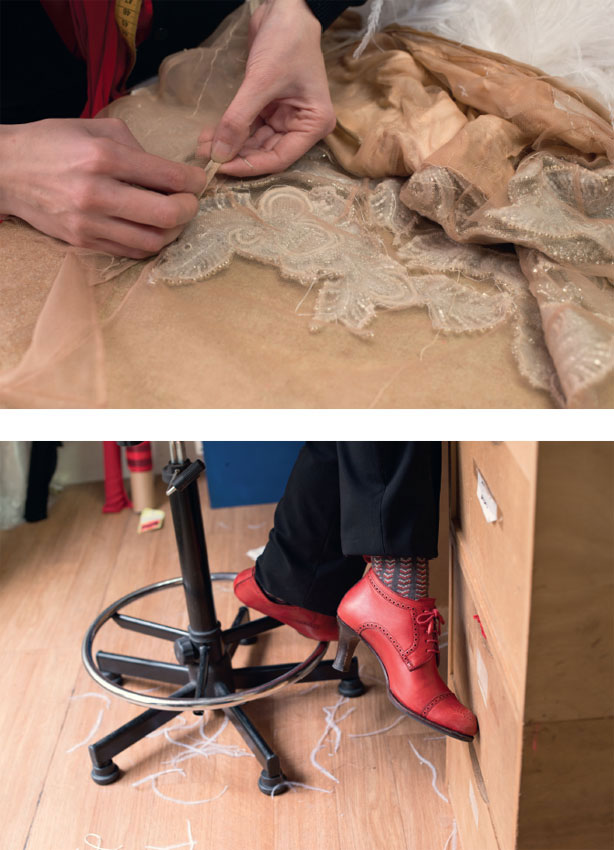

A stitcher puts the finishing touches on a bullfighter jacket for Carmen at the Santa Fe Opera.

The costume shop was doing a rush order around a famous musician’s busy schedule, and he was due in for a fitting shortly. The draper met designer Adele Lutz in the fitting room, ready to try the first costume: a tracksuit embellished with painted flames. Meanwhile, her first hand finished the final assembly on the second outfit. The first hand looked nervously through the small pile of stretchy fabric shapes before her. While she knew how to easily recognize the curved top of a sleeve that gathers into an armhole, or tell left from right pant legs as they join to a waistband, this costume was a full body suit, including a full-faced hood. The pieces she had yet to finish assembling were cheeks and bridge of nose and forehead—not shapes commonly used by a costumer. While the final version would be painted to look like an anatomical chart of the body’s muscles, the mock-up of plain white milliskin had no decoration to help orient the pieces. Trying not to panic, she instead looked for the small markings at the edges. Like any costume’s pattern pieces, they had notch marks used to show alignment. She found the pieces that had mates, and then assumed the remainders had to be the centers: the nose, the chin, and the forehead. From there, she matched triple-notch to triple-notch, single to single, reminding herself that some edges shouldn’t meet anything so there would be holes for eyes and mouth. Luckily the actual sewing didn’t take long, as the pieces were so small, and she joined the head to the neck before David Byrne was ready to try his second costume.

Above and opposite: Stitcher Emma Domingues at Parsons-Meares Ltd. in New York sews rows through layers of fabric to create a quilted texture.

Sewing is the most fundamental part of clothing construction. When the average person pictures clothing being made, they don’t imagine fabric selection or patterning, they visualize someone using a sewing machine, joining pieces together. In actuality, the time sitting at the sewing machine is a fairly small part of the process. Once a person develops proficiency with an industrial sewing machine, which is a muscle car compared to the basic sedan of a home machine, sewing is fast. But, a stitcher’s job also involves pinning pieces precisely together, ironing each seam after it is sewn, and binding edges of fabric so they don’t unravel. The final finishing, done by hand, is of course time consuming as well. Attaching closures like hooks, buttons, and snaps, securing dimensional trim like jewels and braid, finessing linings, and sewing delicate hems are all the job of the hand-finisher.

In university and many professional costume shops, the stitcher job is a learning position, and is closely supervised by the first hand. Stitcher is the entry-level position, and then workers progress to first hand (also called draper’s assistant), and then to draper or pattern maker. In other professional shops, however, stitchers are equally skilled craftspeople and may stay in that position their whole careers. Drapers and first hands sew also if a project is on a tight timeline, but not with the same speed and accuracy as the full-time stitchers. Fine sewing is more than mechanically running fabric through the machine. Often the fabric needs to be given a subtle tension to keep slippery fabric from shifting or coaxed into smoothly rounded shapes like the shoulder of a suit jacket. A stitcher with a good “hand” for fabric is much like a sculptor, forming the flat fabric into a precise three-dimensional shape.

The first hand’s job, cutting fabric, also takes finesse and planning. The first hand ensures there are enough markings on the fabric pieces so that they can be correctly matched up during assembly. Small pencil or chalk marks called notches form a code to tell the stitcher which piece matches to which, and, on curved or stretchy areas, they provide calibration to be sure the shape does not become distorted. After tracing the pattern pieces, the first hand cuts them out, adding the correct amount of extra fabric at each seam—enough to allow adjustability, but not so much that the inside of the garment becomes bulky. On printed fabric, the pattern pieces need to be laid out with care, either to match the design across seams, or to place the graphics of a large print strategically along the body. Should those large swirls be straight down the center of the jacket or offset? Should the darkest section of the print lie at the waist or at the hip? First hands also calculate how much fabric is needed for each garment, and coordinate logistics with the rest of the team—does the fabric need to be beaded or dyed before cutting? Do they need to save half a yard for the milliners to cover a matching hat?

Above and opposite: Costumer Quentin Desfray at work at Atelier Caraco Canezou in Paris.

COUTURE AND STAGE—COSTUMER QUENTIN DESFRAY

Quentin Desfray stands at a cutting table in a sun-lit ground-floor workshop of the Atelier Caraco Canezou in Paris. He traces a series of long, narrow panels on sheer fabric, and then secures them with closely spaced pins so that the delicate surface does not shift as he cuts. A co-worker comes down from the second-floor studio and confirms that she was in fact supposed to cut six bodices from the fabric she holds in her hand. Upon hearing his affirmation, she nervously mentions that the fabric will only be enough for five. He sends her upstairs straightaway to confer with Claudine Lachaud, the boss.

Desfray grew up steeped in influences that would lead him to his chosen career. His mother danced ballet for the Paris Opera, and she and his grandmother were both serious seamstresses. Desfray began his six years of study in costume and fashion while in high school, and continued his training through college. His current job at Atelier Caraco Canezou is perfect for him, as the shop’s reputation for finesse has brought them haute couture clients like Givenchy and Dior that supplement their stage construction work. “I wouldn’t like to do just costumes or just fashion. The advantage here is that we do both. Stage work is great, but I love haute couture also. Fashion is more technical, more precise. The more complicated it is, the more I like it.”

During college, an internship at an opera drew his focus to costume work. After he finished his studies, he went on to work for the prestigious operas at the Garnier Palace and the Bastille. Working as a stitcher, he appreciated when those at his level were included in the collaborative process. Whether or not that happened depended on the designer. At the Bastille Opera, Italian designer Franca Squarciapino created evening dresses for the large chorus in the Lady of the Lake. The designer came up with a modular plan to make five basic styles of dresses with variations so they would look like fifty completely different gowns. She used a wide range of fabrics, and worked directly with the stitchers to find different decorative treatments of jewels, lace, or ruffles for each dress.

He learned a lot at the “enormous” Bastille shop. He gravitated toward ballet work there, partly due to his exposure in childhood, and learned the traditional, labor-intensive methodology of tutu construction. That credential is what first brought him to Caraco, as no one in-house had the specialized training to properly stack the gravity-defying layers of netting. He has now been “nearly full-time” at Caraco for two and a half years, but is still technically freelance. He continues to work at the Bastille Opera from time to time, and for other venues including the Moulin Rouge, Théâtre du Châtelet, and for films. Unlike the opera, where he works as a stitcher, his position at Caraco is as “costumer.” While a select few of the employees do most of the patterning, the costumers do some as well. The costumers routinely adjust patterns, cut the fabric, construct garments, and also do the hand-finishing. The system is more project-based than in most shops, with one or several costumers taking responsibility for a given garment, and seeing it through all the steps of construction.

He appreciates the exacting standards he has learned from the owner of Caraco Canezou. “Claudine hates zippers,” he says, smiling at the vehemence of his boss. “She is passionate about costume and she likes to keep things authentic. If it’s lacing [in the time period] it needs to be lacing.” He recalls a couture wedding dress the shop made for an A-list celebrity client. The dress was all sheer lace, covered in beading. The shop spent two months joining the delicate pieces invisibly together, and adding all of the decoration. Most of the sewing had to be done by hand, and at times as many as eighteen stitchers were involved. One week before the deadline, Desfray melted a small hole with the iron in a layer of netting on the inside. They had to redo the whole back panel—even the most beautifully sewn patch would not suffice. A year later, the horror of the moment is still evident on his face. “But she got married—it’s all good!” he says laughing. Clearly his talents far outweigh his mistake, as he is still a mainstay at the shop.

Costumer Manon LeGuen at Atelier Caraco hand sews a coat lining for an eighteenth-century opera.

Costumer Lucie Lecarpentier trims scales on a mermaid costume for a commercial event at Atelier Caraco.

Lecarpentier moves the costume carefully so as not to disturb drying glue.

Above and opposite: Costumer Anne Blanchard at Mine Barral Vergez costume shop in Paris does delicate finishing on a beaded and feathered 1920s evening dress.

Stitcher Louisa Williams at Parsons-Meares, Ltd.

A LOVE OF SEWING—STITCHER LOUISA WILLIAMS

Louisa Williams sits at her industrial sewing machine, a pile of fabric pieces to her left. The pins form a dashed line along one edge of the wool, adding a temporary sparkle. She takes the top bundle off the pile, nudges a lever with her knee to raise the machine’s presser foot, and positions the corner of the bodice. The colored flecks in the fabric become a blur as the machine accelerates. Without varying her speed, she pulls the pins out as they come near the needle, and a smooth gray seam replaces the line they had formed.

Louisa Williams is a professional stitcher who works at Parsons-Meares, Ltd. in New York City. She has worked at the shop for twenty-six years. Williams started sewing at age sixteen, in her native Jamaica. She learned just because she loved to create clothing, but it quickly also became a way for her to earn money. She was a quick study, because as she puts it, “I took paper, and I cut patterns, and I started to sew. When I was seventeen years old I had a lot of work. I made bridal dresses, everything. I was gifted.” At the age of twenty-nine, with her three small children in tow, Williams and her husband came to the United States to seek better opportunities. She first worked at Michael-Jon costumes and then Brooks Van Horn, one of the top shops at the time, but soon found a home at Parsons-Meares. Williams is grateful to the owner, Sally Ann Parsons, for her consideration over the years. “She never laid me off because I had kids, [which was crucial when] my husband and I separated. My two girls got a scholarship for college. I didn’t have to pay a penny … You know, when you achieve something, you have to love the people who did it, who support you.”

The good will that Williams has felt from the shop over the years is of course a two-way street. She is a lovely, upbeat person who always has a smile for a timid new hire, and her enthusiasm is contagious. During summer months, she often works with headsets on, listening to her beloved Yankees on the radio. Co-workers are occasionally startled by a cheer when the team scores. She glows when recounting the accomplishments of her children and her two grandsons but she also takes great pride in her own work. She loves seeing costumes she has constructed onstage, and saw her favorite, Cats, several times. She also has a great fondness for The Lion King. “I love Cats. I could close my eyes and do Cats … the textures, that beautiful painting. I love Phantom too, but Cats was my favorite.” Williams had ample time to develop this love. Given that most costumes for Cats lasted only a few months due to the extreme athleticism of the actors, Parsons-Meares made a lot of body suits over the show’s nearly twenty-year run on Broadway. Due to the custom painting, the costumes are tricky to construct. The spandex must be coaxed and eased to keep the textured designs perfectly lined up where the pieces join. Williams’ work philosophy is simple, however. “I do it because I love to sew.”

Valentina Abramova and Jacek Polak in the workroom at Barbara Matera Ltd. in New York.

Close-up of Polak, a tailor, at work.

Tailor Roma Dreizis at Barbara Matera Ltd.

Lord Farquaad’s sleeve for Shrek the Musical at Parsons-Meares.

First Hand Ashley Rigg pressing a hem at the Santa Fe Opera.

PART OF THE PROCESS—FIRST HAND ASHLEY RIGG

First Hand Ashley Rigg started in the performing arts as an opera singer. She got as far as her senior year of college and then she realized that she did not really like the lifestyle associated with performing. “I had no idea what to do—I had been singing since I was twelve,” she recalls. She returned home, and was working at a restaurant and “one of my co-workers, a student at the local college, was volunteering at the costume shop and she just couldn’t stop talking about it. And I thought ‘I can do all those things!’ I started sewing when I was very young, but it never occurred to me it was something you could do and get paid. And so I went down to the school and talked to the people in the shop and decided that’s what I should be doing.” Rigg went back to college, and after a few years graduated with her new major. She worked for a while as a stitcher at the Cleveland Playhouse, and did some freelance design work. Then her career took a detour. Her father, who owned a drapery business in Florida, lost his workroom supervisor and Rigg went down to help out. “I missed the collaboration and it was a lot of rectangles—it wasn’t as interesting for me.” She drifted into a position selling advertising for a newspaper. After a time, “my boss handed me a brochure for the Florida Grand Opera—I was supposed to be calling the marketing person.” She could tell from the credits in the brochure that the opera was a large enough operation to have a fully staffed costume shop. “So I called the costume director, and two days later I had an interview and I was back in theater.”

While Rigg had done some designing, she enjoyed it mainly as a means to have interesting things to build. “I want to have my hands in it,” she says. She soon realized that if she wanted to work at the higher levels of the profession, she needed some more training. She went to North Carolina School of the Arts and received an MFA in costume technology. She is now continuing her training in the professional world, learning “more than one way to do things. From grad school people tend to know just one way. The more you know the more valuable you are.” She plans to move up to a draper position, and at some point to teach. This is her third season working at Santa Fe Opera. “I hope to keep coming back if I can find the right position. There aren’t many summer places where the co-workers are of this caliber.”

Rigg’s favorite projects are ones where all those involved work seamlessly together. She recalls a production of Into the Woods during graduate school that gave the witch a mere nine seconds to change from ugly to glamorous, and the actress had to do it herself onstage. “Everyone involved in this had the right attitude. Everybody wanted to make it work and no one wanted to compromise the design, so everyone was really creative in coming up with their own little piece of the process—what can I do to work with you?” For her part, Rigg equipped the “ugly witch” dress with snaps along the shoulder, and then a zipper down the front, but offset from the center. The dress design happened to have a front panel whose edges featured a decorative band. Rigg turned these into flaps that made a perfect place to hide a zipper. “I feel like the audience is looking for something to open at the front or back so if you conceal it it’s more of a surprise.” When the actress opened the dress, it had enough weight to fall to the floor, revealing the pretty dress underneath. She loosened the long train where it was tucked up, and with her other hand she pulled off her hat, which had mask and wig attached, and that was it. The builds were all completed in time for the actress to have ample time to practice, and eventually she got the change time down to four seconds.

Stitcher Hali Hutchinson at the Santa Fe Opera.

Stitcher Ari Lebowitz at the Santa Fe Opera.

A close-up of an industrial serger sewing machine.

Edwin Schiff, Stitcher at the Santa Fe Opera, at the industrial iron.

A stitcher operates the foot pedal of an industrial sewing machine.

A stitcher rips out a seam to alter the fit of a dress.

Costumer Françoise Bianchi sewing at MBV costume shop in Paris.

Sewing fabric is in many ways the common link for costumers. From designers to drapers to craftspeople, most begin their careers by stitching. And, at the end of a production’s build time, the final touches tend to be stitching. In a shop the day before dress rehearsal most likely everyone from the assistant shop manager to the draper to the dyer is sewing buttons and labels, finishing hems, and adding rows of lace.