The Budget Process

A BUDGET IS A blueprint for achieving specific goals. Your unit’s budget is part of your company’s overall strategy. So you need to understand your company’s strategy in order to create a useful budget.

How can you familiarize yourself with your company’s overall strategy?

- Watch the overall economic picture. A company’s strategy during a recession will be far different than in a booming economy. Make a point to listen to your manager’s and colleagues’ views on sales and the economy—and make your own observations as well. Are you deluged by résumés, or is good help hard to find? Are prices rising or falling?

- Stay on top of industry trends. Even when the economy is booming, some sectors are going bust; your budget will need to reflect that reality.

- Steep yourself in company values. Every company has values, sometimes formalized and sometimes just “the way we do things.” The very best companies keep those values in mind during every decision. Suppose your budget calls for a cut in the company’s contribution to health-care plans. If the company’s values view such cuts as anathema to its overall commitment to employees, your proposal will be dead on arrival.

- Conduct SWOT analyses. Every company has strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Keep them in mind as you build your budget.

Understanding top-down and bottom-up budgeting

If your company does top-down budgeting, senior management sets very specific objectives for such things as net income, profit margins, and expenses. For instance, each department maybe told to hold expense increases to no more than 6 percent above last year’s levels. It’s left up to you to allocate your budget within the parameters to ensure that the objectives are achieved. For example, suppose Amalgamated Hat Rack decides that it wants to increase overall profitability by 10 percent. That could mean, among other possibilities, launching a new product line to generate new sales, or cutting overhead by upgrading technology, which would reduce the need for part-time workers.

In addition, if your company does top-down budgeting, make sure to look at the overall plans for sales and marketing, as well as cost and expense plans, as you prepare your budget. The company’s sales plan determines, to a large extent, how much money will be available for the budget. The marketing budget will give you an idea of what the company will be emphasizing in the coming year. Further, many companies strive to reduce expenses as a percentage of revenue every year, no matter how slightly, as a way to improve profitability.

In companies that do bottom-up budgeting, managers aren’t given specific targets. Instead, they begin by putting together budgets that they feel will best meet the needs and goals of their respective departments. These budgets are then “rolled up” to create an overall company budget, which is then adjusted, with requests for changes being sent back down to the individual departments.

What Would YOU Do?

Was the Budget on Track?

SIMONE WAS PLEASED. Recently promoted as manager of her company’s human resource department, she had worked hard to develop the budget for her unit for the coming year. She had negotiated with management for the resources she needed, had made the assumptions behind her requests crystal clear, and had checked to be certain that her budget aligned with the company’s strategy. But Simone also knew that preparing her budget and getting it approved were just the beginning steps in the budgeting process. As the coming year unfolded, she would have to find ways to assess whether the budget she had worked so hard to create was staying on track—or going off the rails. Though she understood the importance of tracking her budget, she felt somewhat uncertain about how to approach this responsibility.

This process can go through multiple iterations. Often it means working closely with other departments that may be competing against yours for limited resources. It’s best to be as cooperative as you can with other departments during this process, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t lobby aggressively for your own unit’s needs.

Preparing a budget

As a manager, you are expected to put together a budget for your department each year. Your compensation may depend, to a large extent, on your ability to stick to that budget. So it’s in your best interest to create a realistic budget when you start out. But don’t sandbag either; it won’t do you or your company any good.

Begin by setting goals. You may want to improve your division’s performance over the previous year, increase net income for the company, or decrease costs—maybe even all three. How do you think your department can accomplish everything it has set out to do? That’s where the budget comes into play. After all, a budget is a plan with numbers.

Start with a list of three to five goals that you’d like to achieve—and put a completion date on them, too. For example:

- Increase gross sales by 5 percent by June 30.

- Decrease administrative costs by 3 percent as a percentage of revenue by the end of the fiscal year.

- Reduce inventories by 2 percent by the end of the fiscal year.

Be sure you know the scope of the budget you’re supposed to produce. Scope implies two things: the part of the company the budget is supposed to cover and the level of detail it should include.

- The smaller the unit that you’re focusing on, the more you need to budget at the detail level. If you’re creating a budget for a twelve-person sales office, you typically won’t need to worry about such capital expenditures as major upgrades to the building or the computer equipment. But you should include estimates of what kinds of office supplies you’ll need and how much they will cost.

- As you move up the organizational ladder to include more people and larger departments in your budgeting, your scope broadens. You can assume that the head of the twelve-person office has thought about paper clips and travel expenses. You’re now looking at capital expenditures, studying the broad-brush outline and looking at how it all rolls up together.

Other issues to consider:

- Term. Is the budget just for this year, or the next five years? Most budgets are for the upcoming year, with quarterly or monthly reviews.

- Overview. Does your budget need to be accompanied by an overview of your strategic plan—for example, your plans for increasing sales or market share? If so, you need to be prepared to defend it.

Take a hard look at your assumptions for the coming year. After all, a budget, at its simplest, takes current data, adds assumptions, and creates projections. Let’s suppose you think sales will rise 10 percent in the coming year. If that’s true, you may have to add two more people to your unit. But when you get before your budget committee, be prepared to defend your assumption that sales will rise 10 percent.

Steps for Creating a Budget

- Analyze your company’s overall strategy.

- If your company does top-down budgeting, start with the targets given to you by senior management. If your company does bottom-up budgeting, create these targets yourself.

- Articulate your assumptions.

- Quantify your assumptions.

- Review: Do the numbers add up? Can you document your assumptions? Is your budget defensible?

Role-playing may help you here. Put yourself in the position of a division manager with limited resources and many departmental requests for funding. How can you make your case for two additional staff members so that the division manager grants your request ahead of all the others?

Articulating your assumptions

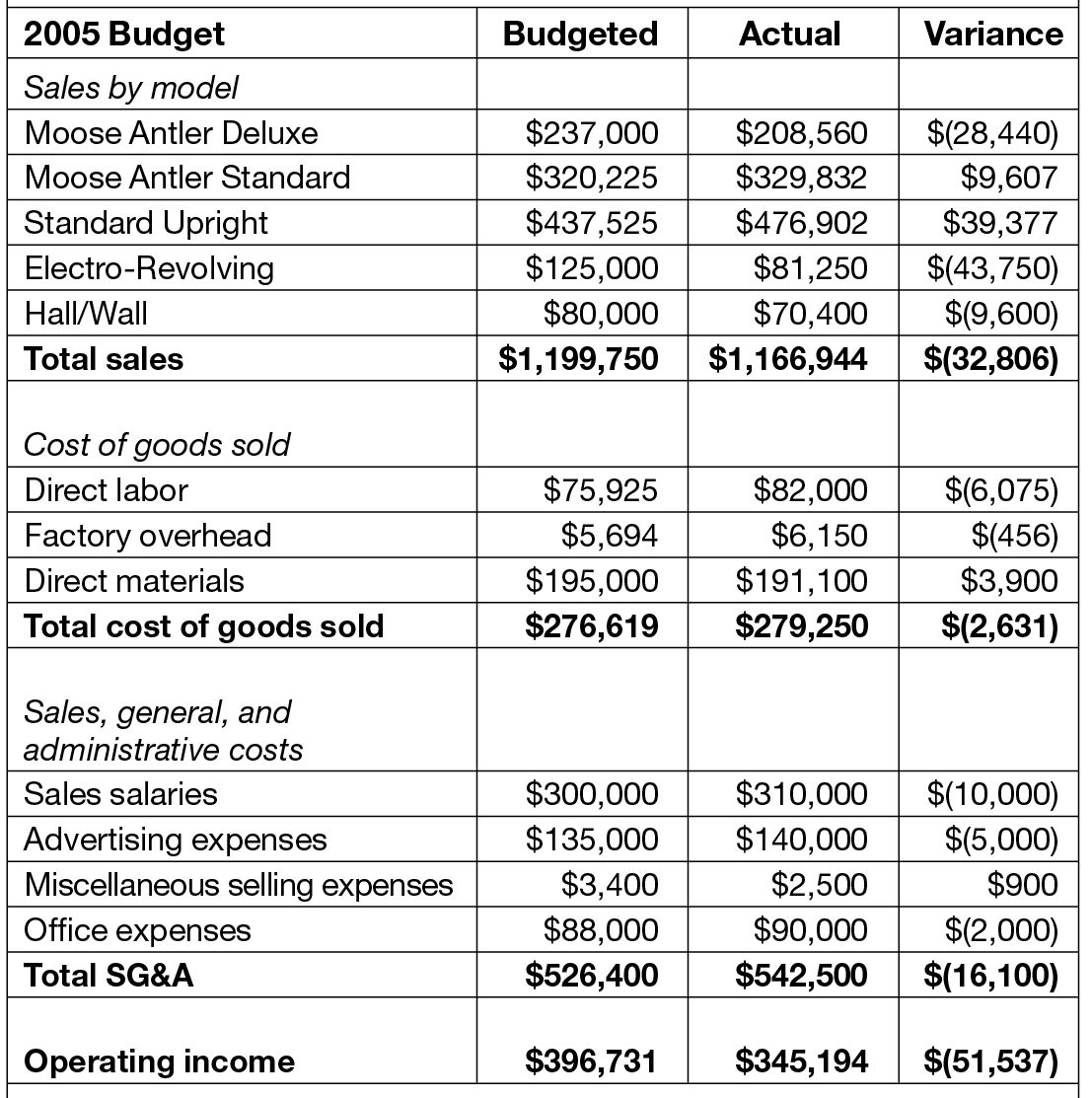

The easiest way to get started is to take a look at your department’s most recent budget. If you’re the manager of Amalgamated Hat Rack’s Moose Head Division, you might decide to look at the 2005 budget (shown in the table “Moose Head Division, Amalgamated Hat Rack”) to get ideas about how to increase revenues, cut costs—or both.

Moose Head Division, Amalgamated Hat Rack

Source: Harvard ManageMentor® on Finance Essentials, adapted with permission.

Don’t start off by looking at specific revenue or cost line items, because revenues and costs are integrally linked. Instead, begin by asking yourself what events you want to see happen over the time frame you’ll be budgeting for and what revenues and expenses are associated with each.

For example, do you expect to sell more products? How? If you plan to increase sales of your company’s current products, there will be additional sales and marketing costs—maybe even new hires—associated with this strategy. Or if you intend to expand the company’s product line, you will need to budget for a new product development initiative.

In the case of the Moose Head Division, the Standard Upright and Moose Antler Standard exceeded sales expectations in 2005. If these have the highest sales numbers, would it make sense to increase the sales projections for them, or should you stick with the 2005 sales volume for your 2006 projection? If you’re looking to increase sales volume, the Standard Upright is a good choice: it beat its 2005 projection by 9 percent. Could you increase the anticipated sales for this model by 5 percent or 10 percent in 2006? In order to achieve this increase, how much more would you need to spend on marketing? To make the decisions, you’ll also need pricing, market, and other relevant data.

Alternatively, do you expect to eliminate some products? At Amalgamated, the Electro-Revolving model is faring poorly. Would it be better to eliminate this line entirely and promote the newer Hall/Wall model? It would eliminate $81,250 in sales, but since the Electro-Revolving is very expensive to produce, perhaps the net result of discontinuation would not affect the bottom line very much.

Other questions to ask yourself include:

- Will you keep prices the same, lower them, or raise them? A price increase of 3 percent would have more than eliminated the budget’s 2005 gross sales shortfall—provided that the increase did not dampen sales.

- Do you plan to enter new markets, target new customers, or use new sales strategies? How much additional revenue do you expect these efforts to bring in? How much will these initiatives cost?

- Will your salary expenses change? For example, do you plan to cut down on temporary help and replace these resources with full-time employees? Or will you be able to reduce salary costs through automation? If so, how much will it cost to automate?

- Are your suppliers likely to raise or lower prices? Are you planning to switch to lower-cost suppliers? Will there be a drop-off in quality? If so, how much will it affect your sales?

- Will your product have to be enhanced to keep your current customers?

- Do you need to train your staff?

- Are there other special projects or initiatives you are planning to pursue?

Quantifying your assumptions

Each of your assumptions and scenarios must be translated into dollar figures. If your entire staff of twelve needs sales training, you need to find out how much it will cost to train each person, and multiply that number by twelve to calculate the total cost. Some costs or revenues are easier to project than others—which is why it’s always a good idea not to prepare your budget alone. Coworkers and direct reports will have valuable suggestions. Trade publications can often provide industry averages for a range of costs.

Once you’ve translated the assumptions into numbers, you need to incorporate those numbers into budget line items. Because your budget needs to be compared and combined with others, your company will probably provide you with a standard set of line items to use. In some cases, your quantified assumptions will constitute the entire line item—for example, you may have listed and quantified all the product development projects you’ll be pursuing next year. In other cases, your assumptions will be incremental: if you plan to boost sales by raising prices, you’ll start with last year’s sales figures and then increase them by the appropriate amount.

Tip: As you put your budget into its required format, be sure to document your assumptions. It’s easy to lose track during the translation, and you will want to be able to explain them—and revise them—when needed.

When you have compiled your budget, take a step back. Does the budget meet the goals that have been set for your unit? For example, if your goal was to increase gross sales by 5 percent, does the budget in fact do so? It’s easy to overlook overall goals as you get into the line-by-line detail.

Furthermore, is your budget defensible? You may be perfectly happy with it, but not everyone else on the budget committee may be. Once again, you have to push your assumptions. Could you do as well with one extra staff member as with two? If not, be sure you can prove it.

Tips: Budgeting

- Stay goal oriented. If you aim to increase sales, make that the overriding concern of your budget. Don’t let other issues sidetrack you from your main goal.

- Be realistic. Most new managers would like to double sales or cut expenses in half. But remember: you’ll be held accountable for the results.

- Don’t try to do it alone. Include your team members—they may have detailed knowledge about certain line items that you don’t.

- Don’t use the budget as a substitute for regular communication with your staff. Team members should hear directly from you about the funding for line items that affect them most directly—not by reading the finalized budget.

- Don’t blame denied requests on the budget. Be direct: tell an employee if a requested business trip is unlikely to be worth the expense, instead of saying, “We just don’t have money in the budget.”

What You COULD Do.

Remember Simone and her need to track her budget for the HR department?

The mentors suggest this solution:

Simone needs to assess the performance of her budget at least monthly. In particular, she should pay special attention to large positive and negative variances, and figure out what’s causing them. For example, a variance might be a one-time variation—in which case Simone wouldn’t need to change anything. Still, she should keep monitoring such variances over subsequent months to make sure they do indeed straighten themselves out. If a variance doesn’t represent a one-time aberration, Simone will need to assess why the variances are occurring and develop responses to them—which she could do by brainstorming ideas with her team.

In addition to tracking and addressing variances, she should also reassess forecasts quarterly as well as inform senior management if it looks as if she’s not going to make her annual budget goals. That way, management can adjust the overall company forecast accordingly. Finally, Simone should also inform senior management if her unit’s performance is turning out better than expected. And by saving her original budget assumptions and estimates, she’ll be able to improve her budgeting ability for next year.