Introduction to Urban Lighting and Evidence-Based Lighting Design

Urban lighting and illuminated nights have become a necessity for many regions around the world and street lighting is now considered a basic infrastructure in developed countries. Owing to its wide scope, urban lighting has always been a popular topic in the field of lighting design. Issues that receive the most attention include lighting for urban monuments, architectural lighting and themes around urban beauty and aesthetics, as well as lighting for drivers and visual performance. Another theme that has raised significant interest in recent years is light as a part of people’s daily lives: the light that enables people to travel around their neighbourhood or their city on a daily basis; the light that allows them to see themselves and their neighbourhood. This book looks at pedestrian lighting from environmental psychology, behavioural and societal points of view, explaining different issues around the subject. It explores the needs and experiences of people regarding the night streetscape and looks at how these needs can be addressed by public lighting.

The focus of this book is evidence-based design: the chapters explain what constitutes an evidence-based approach and how it can be used in lighting design. While the book has been written by experts, it is intended for a wide audience.

The results of academic research are usually used to create new standards and guidelines for lighting designers and local authorities. However, when it comes to ‘soft’ topics such as people and the lit environment, there are many factors involved, which cannot necessarily be simplified into a guideline booklet. The design equation becomes much more complicated when it takes into account who will be benefiting from the street lighting, what they will be doing, where and why. This book emphasises how the design context and environment can affect the way guidelines can be used and aims to enable designers and policy makers to make informed decisions in their projects.

Evidence-Based Lighting Design

Evidence-based design (EBD) is a research-based approach designers use to understand how people interact with the built environment and how the built environment influences behaviour. It is adapted from evidence-based medicine, where scientific research supports decisions about the most effective and efficient treatment. EBD emerged in the health sector in the 1980s, when designers made use of a credible body of research linking design to improved patient safety and faster healing. For example, single hospital rooms are consistently proven to reduce infection compared to wards. When applied to lighting, the evidence-based approach found that lighting does indeed affect human health and wellbeing. Studies exist about the psychological effects of lighting, carpeting and noise on critical-care patients, and evidence links a well-designed physical environment with improvements in patient and staff safety, wellness and satisfaction.1 Architectural researchers have studied the impact of hospital layouts on staff effectiveness2 and social scientists have studied guidance and wayfinding.3 Architectural researchers have conducted post-occupancy evaluations (POE) to provide advice on improving building design and quality.4 While the EBD process is particularly suited to healthcare, it is also useful in other fields of design.

So how can EBD be applied to create a sense of safety and security in urban spaces at night, to make a neighbourhood more legible after dark and to encourage a more inclusive night city?

What is evidence-based design?

Evidence-based design is a process for the judicious and conscientious use of current best evidence from research and practice when making decisions about the design of an individual project. EBD is also known as research-informed design, although some experts define these two terms differently. They argue that because the literature for research-informed design comes from education and not from the healthcare disciplines, research-informed design differs from EBD.5 For further details, see George Baird’s Building Evaluation Techniques.6

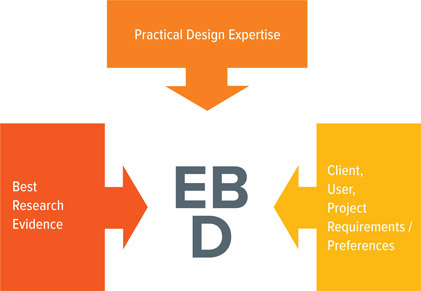

Evidence-based design does not consist of ready-made answers to complex problems. Instead, it is a process whereby the designer and the client find the answers themselves. EBD is the integration of practical design expertise, the client, the project, the user requirements and preferences, and the best research evidence into the design decision-making process (see Figure 0.1).

An evidence-based approach simply means that we look beyond the limitations of our own knowledge for reliable information upon which to base our design process. The aim of EBD is to create a bridge between research and design practice, augmenting the existing knowledge of organisations, communities, designers, their clients and end users with available evidence about the ways in which people interact with the new and complex environments that we now occupy. Reliable information about anthropospatial behaviour can inspire new thoughts and ideas.

Figure 0.1

Integral components of evidence-based design (EBD)

Evidence-based lighting design does not tell you the exact product to choose, or the illuminance and luminance and distribution of light. But the process of turning to credible research and experience may offer a pathway to answer these questions, which most certainly will not come out of a standard manual. EBD is an approach to assist designers to make decisions about design solutions based on the available knowledge about the impact of those solutions on people, costs and management, among other factors.

Now the question is are research outputs the only source of evidence?

What is evidence?

The etymology of the word ‘evidence’ goes back to the concept of experience, relating to what is manifest and obvious.7 The Oxford English Dictionary gives a number of definitions for the word ‘evidence’, such as clearness and obviousness, facts making for a conclusion, information tending to establish fact, etc. A unifying theme in all definitions of evidence is that it needs to be independently observed and verified. This highlights the importance of ensuring that the evidence used to inform practice (and policy) has been subject to scrutiny.

However, what counts as evidence and in what circumstances? Evidence is considered to be knowledge derived from a range of sources. Knowledge has been defined as ‘an awareness or familiarity gained by experience, a person’s range of information’. Knowledge can be categorised into two types: propositional/codified and non-propositional/personal.8 In reality, the relationship between the two sources of knowledge is dynamic; however, propositional knowledge has gained higher prominence. Propositional knowledge is formal and derived from research and scholarship and is mainly focused on generalizability. Non-propositional knowledge is informal and comes primarily from practice. It forms part of personal knowledge linked to the life experience and cognitive resources that a person brings to the situation to enable them to think and perform.9 In order to practise evidence-based design, practitioners need to employ and integrate multiple sources of both types of knowledge, informed by a variety of evidence bases that have been critically scrutinised. Furthermore, these processes are context related within a complex, multifaceted design environment.

Different sources of knowledge

The characteristics of knowledge generated from four common types of evidence available for use in practice are described below.

Knowledge from research evidence

Research evidence has been ranked as the priority over other sources of evidence in the delivery of evidence-based practice. Additionally, research evidence tends to be perceived by some as providing final answers to design questions. However, such evidence is rarely constant and may change as new research develops. Therefore, research evidence needs to be viewed as provisional. The production and use of evidence is a social as well as scientific process, which does not allow it to attain the required level of ‘objectivity’. Thus, there is no such thing as ‘the’ evidence. Research evidence is socially and historically constructed.10 It is not certain, acontextual and static, but dynamic and eclectic. Finally, research evidence, although crucial to improving design process, may not on its own inform practitioners’ decision-making.

Knowledge from professional experience

Knowledge accrued through professional practice creates the second part of the puzzle in the delivery of EBD. This knowledge is expressed and embedded in practice and is often implicit and instinctive. Practitioners not only act on their own professional knowledge, but also resort to the expertise of others to inform their practice. This type of knowledge can usually be attained through post-design evaluations of different projects. However, it can be argued that such sources of knowledge, if not generated systematically, are subjective, biased and lack credibility. In order to avoid this problem, such knowledge and reasoning requires integrating the four different types of knowledge discussed here within the contextual boundaries of the design environment. While practical knowledge is an important source of information, the interaction of practical knowledge with research is not straightforward or linear. Therefore, its role in, and contribution to, evidence-based practice requires to be revealed and articulated.

Knowledge from clients and users

The third source of evidence that contributes to practice is the personal knowledge and experience of users and clients. This source of knowledge can be collective or individual. Collective involvement is about the participation of groups or communities in the design and planning process. In contrast, individual involvement concerns individual clients and users and their encounters with individual practitioners during the process of design and delivery. Using collective knowledge from clients/users is a common practice in policy-making and usually has justifiable methodologies and approaches. However, the gathering and incorporation of individuals’ values, experiences and preferences into evidence-based practice is a complex issue and melding these with other sources of evidence into design decisions requires expertise.

Knowledge from design context and environment

In addition to knowledge that comes from research, professional experience and clients/users, the design context and environment contains sources of evidence. In the process of design, practitioners may draw on local surveys and information, knowledge about the cultural and social aspects of the project’s setting, the views of stakeholders, local and national policy and so on. While locally available data sources clearly have a role to play in the development of evidence-based practice, attention needs to be paid to whether the data is systematically collected and appraised, how it is integrated with other kinds of evidence, and how such data can inform the current design project.

Why is EBD so Important?

The use of evidence is important because information about the impact of design solutions on users and maintenance may influence the way design evolves. Disconnected pieces of evidence should not be mistakenly used as EBD to justify bias within design solutions. Rather, evidence should support decisions and, whenever possible, designers and planners should collect relevant information from completed projects in order to update the evidence base. In other words, this means checking whether or not their decisions efficiently and effectively improved the quality and use of the space. Currently there are limitations in maximising the utilisation of EBD. These are related to the lack of explicit cause-and-effect relationships, the fragmentation and sparseness of the available information and methodological limitations. However, the use of systematic reviews can mitigate those problems and bring strength to EBD. EBD is evolving fast, with a rapidly growing body of evidence. Moreover, the implications of EBD to the design process have not yet been deeply explored. However, issues related to changes in the configuration of the design team (for example, by considering the participation of a researcher) and the provision of evidence to designers have started to be explored. Furthermore, discussions about whether EBD aligns with or contradicts new design and production theories and methods (such as lean design and production) and the link between parametrical design and EBD are also emerging. Finally, studies linking the built environment with its effects on people involve a considerable number of variables that can be organised in different ways.11

With the advance of lighting technology and its consequent lower cost, every year we can observe a steady increase in the use of artificial illumination in the outdoor built environment. The importance of the quality of social interaction in our daily lives is well recognised as a significant driver in the design of environments. However, the question is what we base our speculation on this evolving social context.

Lighting research evidence usually comes into practice through the creation of new guidelines and standards. These are particularly useful in technical matters; however, when it comes to ‘soft’ issues like how people interact with the lit environment, guidelines alone cannot reflect the vast nature of human perception and behaviour in every setting. Urban lighting design is a very complex issue which requires a holistic approach by urban lighting designers and planners.

What is this Book all about?

A key issue is how methodical research can be translated into practice and design. There are quite a few challenges that stand in the way of lighting design being more research-based. Research methods may not be fully understandable to lay people, with results normally published in academic papers, using jargon that is not very friendly for design practitioners. There is a culture clash between the way research is set up using a very scientific approach and designers who have been trained to work quite differently. On the one hand there is method, rigour and science, and on the other hand there are practising lighting designers who have intuition, experience and judgement and who are working with their clients’ expectations. This book initiates a bridge between the world of academics/lighting researchers and that of lighting practitioners, by reviewing lighting studies. It is a new resource for lighting designers, planners, local authorities and their clients, and, indeed, anyone who wants to learn more about the ways in which people interact with the lit environment.

In seven chapters, academic experts and practitioners from the field of urban lighting present case studies, definitions, methodologies and research related to cities and their inhabitants. The views covered range from a societal and municipal standpoint to a pedestrian’s experience of the city, drawn from observations and evaluations of completed projects, as well as examinations of the legibility and walkability of public spaces.

Each chapter begins by identifying an issue and considering its significance for the built environment and ends with a valuable summary and specific design suggestions (as a list of bullet points) to enable the generation of appropriate, original, human-friendly lighting solutions for urban areas outside daylight hours.

The concepts put forward in this book aim to address some of the concerns surrounding urban lighting for people after dark. There are other solutions, of course. My intention is to raise basic issues regarding how people interact with spaces and the lit environment and how urban settings must be carefully analysed for both daytime and night-time use by people according to their day-to-day lives. It must be noted that those engaging in urban lighting design ought to proceed with an awareness that not even the best lighting design can correct all problems intrinsic to urban settings – perhaps they can only minimise them.

Note on the reproduction of images in this book: the colour of the images is representative of genuine light conditions and has not been colour corrected by RIBA Publishing.