Chapter 6. Creating a High Performance Team

Research at IBM showed that 25% of the variance in their business results can be attributed directly to variations in the climate and its impact on satisfaction, creativity, motivation, and retention (Nair, 2006). They concluded from various surveys conducted within IBM that the climate is responsible for attracting and retaining talent and improving productivity, effectiveness, and creativity. This productivity translates into results such as growth in sales and earnings, return on sales, and lower employee turnover. Other research showed that a positive work climate can account for nearly 30% improvement in financial results (Creating, 2002; Goleman, 2000). The argument is that a positive climate increases the extra effort that people give above and beyond the formal job expectations. People who are highly motivated are willing to take on the big challenges, innovate, and take risks. Those who are demotivated not only do not do the extra work, but they can also act as anchors pulling the team down. This is supported by a Gallup survey studying employees in 2,500 business units and 24 companies throughout the United States (Buckingham & Coffman, 1999).

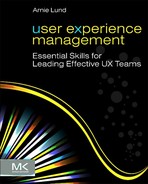

The Hay Group defined climate along six dimensions: clarity, standards, responsibility, flexibility, rewards, and team commitment (Fig. 6.1; Nair, 2006). This climate includes everything that impacts a group’s ability to perform better. According to Goleman (2001), “An analysis of data on 3,781 executives, correlated with data from climate surveys filled out by those who worked for them suggests that 50 to 70 percent of employees’ perceptions of working climate is linked to the characteristics of the leader.”Stringer (2002) argued that the manager’s behavior is what drives climate, and Watkins (2000) argued that leaders have it in their power to create a climate that motivates, grows, and retains the talent on their teams.

|

| Figure 6.1 Dimensions of climate. |

As a manager or lead you can:

• Help create a shared vision, a common understanding of the mission, and team identity.

• Leverage the aspirations, skills, and interests of the group to assemble the right mix to tackle a given problem.

• Focus your team on achieving the vision and big challenges.

• Recognize accomplishments and inspire confidence.

• Work to improve communication and collaboration.

• Drive improvements in practices, policies, and planning.

• Leverage feedback loops to improve.

• Set up and improve the management systems that guide the operation of the team within the larger organizational context.

• Help influence the experience culture within the team even within the context of the larger organizational culture.

• Create opportunities for people to grow, and help drive clarity in roles and responsibilities.

• Ensure that they will have the information needed for effective planning and functioning.

• Have the ability to inspire.

To shape the climate, you need to understand what influences the climate in your organization and the state of the climate; then you need to take action. Action frequently involves beginning with understanding what motivates the individuals on your team, and then crafting interventions based on those motivations.

Hints from Experienced Managers

Hints from Experienced Managers

My toughest challenge: managing a team in a fast-paced, strategically fluid, and high demand environment. In this environment my colleagues and I struggled with a number of questions about how to improve our process and practice to (1) “quiet” the noise and (2) become less reactive and more strategic and (3) make us agile in meeting customer and business needs. Over time, we implemented process and practice changes that made a significant difference here, but we also encountered some important influencers that were harder for us to control — e.g., executive override, divergent goals and incentives across organizations, unclear or changing strategies.

Marilyn Salzman, User Experience Strategist, Salzman Consulting, LLC, Louisville, CO

Define Your Team Identity

Not many management training classes I have taken had staying power. Most have covered things I already knew, but provided opportunities to practice these skills. There was one course on risk taking that had the surprising effect of causing me to quit and move on to a new job. In one class I learned to juggle (it was supposed to teach us the importance of keeping multiple projects going at the same time, but the best part was clearly the juggling). In another class I learned how my style of problem solving changes when I move from the day-to-day stress to extreme stress.

There was an interesting management excellence course that presented a model that I have found very useful. The workshop itself minimized what was formally taught to maximize the learning through experience. At the beginning we were formed into teams and a management structure was put in place across the teams. Each team took on a project. Overlaid on the process were formal exercises in self-reflection about the process. There was a little training in a few basic skills, but the most important part of the experience was achieving the realization that this was a laboratory and what we learned was up to us. It was a chance to see how others saw us and to intentionally change behaviors to modify the perceptions and to see what happened. In the middle of the workshop there was a chance to meet with the facilitators one-on-one to talk about specific challenges with our teams. I had a new challenge and the coaching was a unique opportunity.

The problem was that my team had doubled in size in about two months. I had hired several excellent designers and researchers, and focused half the team on the most important project we had. The lead for the team was the person who had been on it almost from the beginning, but some of the people hired and now working on the team had as much if not more experience in design. Not too surprisingly they were deep in the storming phase of team development. I sat down with the facilitator on a couch we found, she took her shoes off and twisted around, faced me, looked in my eyes, and leaned forward. I definitely felt her attention.

I shared the challenge and she asked a series of questions to explore the context. She had all the right attributes for a good field researcher. She then shared something called the Stafford Beer Model of management. Stafford introduced management cybernetics in the 1950s based on a theory of communications and control (Rosenhead, 2006). According to the model, there are three components to shaping a successful team: managing the present, creating the future, and creating identity. Managing the present is the implementation and optimization done to deliver on the bread and butter UX responsibilities that satisfy most of what those who fund us are looking for. Creating the future is a component that sets the vision of where we want to go. This is the UX leadership we can provide on teams. There is the vision of where we want UX to be within the organization, the vision of the experiences we are trying to create in general, and the vision for the individual projects. We had most of the processes and tools in place for managing the present, and people were executing very successfully. We also had a clear vision of where we were heading, and a strategy for how we were creating the future.

The third component needed to create a highly functioning team was creating identity, which ensures that everyone on the team has shared purpose, values, and behavior. In other words, it is about creating a team culture that bonds people, and shapes the way they see the world and see each other. It is about ensuring that everyone has an answer to the question of why we are here and why it matters to each individual that we are part of the group. It is also about the symbols and tools we share that signal who we are.

Once she pointed it out, it was clear that when my teams perform at their highest levels, they have an identity. When I was at Ameritech, the experience of having the corporation become design centered and focus on our work drove the identity. The branding on the Web site around our lab and user-centered approach (represented in Fig. 6.2 and shown on the corporate Web site and through our ads) became a visible reminder of who we were and what we stood for.

|

| Figure 6.2 Ameritech’s user experience test town. |

One high-level technique the facilitator shared that worked well was to have my team sort themselves into the four corners of the room based on whether they had no idea what the identity of the team was, some sense of the identity but did not know how much of it they shared, a clear sense of the identity of the team but had not fully bought in, or a clear sense of the identity and had fully bought in. Then as a facilitator I randomly selected people from the groups to talk about why they felt as they did, and what it would take to move to the higher level. The sharing helped us understand each other better. The distribution really gave me a feel for where the team was. In listening to each other, some at lower states of buy-in and understanding edged a little higher, and we all got a better idea of what it would take to continue to move the team. This technique also worked well for assessing where people were in buying into the vision and mission, and could even be used to see how people were feeling in general about the climate. With this information I now had the insight needed to grow the team’s identity.

Recently a climate poll was taken, and we discovered that the new funding model imposed upon us resulted in a big hit to the morale scores. Besides my own surveying of people and discussions with the team, I brought in another organizational consultant and had her do an independent set of interviews and root cause analysis. It turned out that people felt like they were working alone. They felt like there was very little collaboration, and that others on the team would not cover their backs if necessary. They felt like they were not part of a team, or that they would not be rewarded for team behavior. Unfortunately, the new funding model destroyed the team identity.

Knowing this, I worked with my management chain to ensure that we would operate not as a service organization but as a team focused on a common theme. We would still provide some support for individual projects funding us, but focus as a team on a common set of experiences to drive across the projects. Everyone was in this together. I explicitly worked toward identifying each individual’s challenges with those they support, and then brought others to bear to help address the challenges. And when people jumped in to help out, I leveraged an internal awards system to make sure that everyone knew how much I valued this cross-team collaboration. This resulted in a strengthened identity. Clearly, creating identity is one component that needs to be monitored and continually nourished.

Taking the Team Pulse

In the mid-1990s there was a wave of corporate downsizing (aka layoffs) going on around the United States and many user experience teams were targeted. There certainly seemed to be an air of doom and gloom in the conferences. Since Ameritech was going through its own process there was also a vibe in the air that was working against the creative energy that was necessary for us to be successful.

Many of the companies conducted work climate surveys. These are usually questions about the local organizational effectiveness, the effectiveness of the more global organization, senior management and the strategic direction, job satisfaction, compensation, diversity, and other topics that Human Resources is concerned about and that are relevant to the culture the company is trying to drive. Experience shows that people often rate their own team as being great, but they have more doubts about their sibling organizations, and people in different parts of the company are seen as ruining the company. It seems that the further away others are organizationally the less positive people are about them.

I concluded that the survey questions conducted at Ameritech were not getting at the factors that I sensed were important for my user experience team’s attitude about their work climate. As I result, I developed my own survey within the R&D organization and customized it for my own team (Lund, 1996a). I then monitored changes in the results quarterly to drive tactical activity around creating a better climate, and to understand how events in the larger organization were impacting my team’s attitude. I also ran the survey on another segment of the user experience of the community to compare attitudes of my team to the larger external professional community.

The survey was intended to measure several factors. The first factor and the one that accounted for the greatest amount of variance was “Conditions for Excellence.” It consisted of items like “I am fully using my skills to benefit my company. I am growing in my job. I am challenged by my work.” This factor is basically at the heart of what is needed to create a flow state (Csikszentmihalyi, 1982) — where a person’s skill is roughly matched by the challenge they face, and both increase over time. When you are really enjoying your job, you are in that state and time flies by, the work is creative and insightful, and everyone is energized. Other studies have shown that having the right work is one of if not the most important factors in job satisfaction. I have found that when I get up in the morning and I am not excited by the work that lies ahead, I start thinking about the next gig. As a manager, therefore, one of the things you should continually try to work on with your team is to get the best match possible between what the business needs and what excites the individual — you are trying to achieve a portfolio of projects that balance individual excitement with your strategy.

The second factor was “Work Valued.” It had items like “My creativity is valued. My work is respected by my management.” The UX twist on this factor is clear, and since management includes management above the UX manager it also reflects a desire to be respected within what may be an engineering organization. This is a factor that the manager can actively influence. You are one of the most important people in showing what is valued and how to interact with each person on your team from day to day. You also have the ability to make people’s work visible to management higher in the chain (and to let people know you have done it).

The third factor was called “Stress Manageable,” although more recently it is positioned as work-life balance. It includes the items “I am not stressed excessively. My job does not interfere with my home life. I am not overworked. I am ‘in control’ of my work situation.” The last item recognized the literature that much of stress (e.g., during times of change) is feeling that things are out of control. You may be bothered by the hours you are putting in for a deadline, but if at some level you feel that what is happening is because you have chosen it, you can handle it better than if you are feeling randomized from managers in the clouds.

The fourth factor was related to work valued, but recognizes the unique relationship we have in UX if we are centralized. It is called “Partnership,” and includes “I feel in contact with the organizations that use my work. The organizations that use my work value my contributions highly. I feel personal ‘ownership’ for ensuring the success of the organizations that use my work.” To ensure you are meeting the needs of your partners, evaluation of your team’s performance should be through 360 feedback from the teams. Are they MVPs on the teams they support? This is only half of the information you need as a manager to help ensure that the entire system works effectively. The other half is understanding what your team members are feeling as they work with others on a project. If your team feels they have no impact with teams, and that the work is not being recognized and used by those they are doing it for, it strikes at the heart of their feelings of self-worth. If a manager finds an issue here, it is critical that you get deep into the root cause analysis and address it.

I have mentioned elsewhere that at Ameritech we had a wonderful lab. Any physical resources we needed seemed to be there. Yet I would sometimes get feedback that something was missing. So the fifth factor, “Resources”, attempted to address the issue with statements like “I have the resources (e.g., hardware, software, and lab) to fulfill my responsibilities. I have the information I need to fulfill my responsibilities. I know how to use my role in the company to fulfill my responsibilities.” What matters most to people is whether they feel they are in control of their careers and daily work lives, and a key element in that is whether they have the information they need (especially from upper management), and whether they feel like they understand the rules of the game and how to play it to get things done. Issues in this area often are tied to having a trusted, candid relationship with the team, and knowing what information to share, how to share it, and when. It is also about leveraging the team to share best practices and to help each other in navigating the company to get the job done.

A final factor was truly a check on the pulse of the organization. It was about “Motivation” and included “My bias is toward ‘making it happen,’ in spite of obstacles. My work is important. My work is important to me personally. I am committed to helping the teammates with whom I work excel.” It was another angle on the first factor, getting at the fundamentals of how people view their work and how it motivates them as well as working in a bit of motivation around team identity and collaboration.

The Gallup Organization created a standardized instrument called the Q12 that was used by many companies to assess climate (see http://gmj.gallup.com/content/811/Feedback-Real.aspx). It is a survey of 12 questions that identifies how engaged employees are based on a large number of focus groups and thousands of interviews, and correlates highly with superior job performance. Many of the questions touch on the same categories found in the Ameritech study. They address clarity of expectations and support for growth, availability of resources, recognition and the value placed on work, and other issues.

What People Want

Reviewing the literature, the factors that other people have identified match well with what I found in the survey I derived from my team. There was an article in the January 28, 2008, Christian Science Monitor (2008) titled “Seven Things Employees Want Most to be Happy at Work.” It noted that researchers are increasingly finding that it is the intangible aspects of the job such as respect, trust, and fairness that are important to people. Another study they report found that the top three things people want are interesting work, being appreciated for their work, and a sense of being a part of what is going on. The seven intangibles they list in the article are

• Appreciation

• Respect

• Trust

• Individual growth

• A good boss

• Compatible co-workers

• A sense of purpose

Joy and pride in the work and the exercise of our profession is at the heart of what matters to people, and it is tied to the path we chose for our lives. Most of us want to have impact. We entered the field because we want to make a difference in people’s lives; we want our work to change technology so that the world is getting better in some way. That means we want whatever we do, whether it is ideation, exploratory design, uncovering new needs, design and development, or evaluating existing products to find its way into what is created by the companies in which we are working.

We also want to be respected and rewarded for the work we do. As other studies have shown, it is not necessarily the money, it is recognition for the importance and uniqueness of what we do and knowing that it is indeed valuable for the business and for users. As a manager, one of the roles you play is trying to paint that road more explicitly and clearly. You can make it a point in team meetings, one-on-ones, and even in broadcasting status notes to try to draw out those connections. Certainly it is important to work hard at taking the extra steps to recognize good work. When you see good work that is not getting praised, encourage the clients to say something nice about the work. Make sure people know about the praise you are receiving about them. When I get praise about people, I try to share it with senior management as well as to draw out the business impact of the excellent work.

Praise that feels specific and detailed means more than a general “Way to go!” I received a copy of one note, for example, from a general manager in the business and that person’s boss (a vice president) about how wonderful it was that we had done a particular usability test (conducted and reported by one of my researchers, Alexander), and how vital it was to listen to the users. I forwarded that to my boss, his boss, and even his boss. The most senior executive in turn circulated it with his praise about the importance of the work to every manager in the IT organization. That communicated a message of recognition not just to Alexander but to my entire team, and served to strengthen the UX brand across the entire IT organization.

At a more local level, one of my new employees, Sindhia, bought several small inexpensive items from a store: a lantern, a Rubik’s cube, and a football. She then started a process where every few weeks at one of our staff meetings whoever had an object would present it to someone else on the team for something good they did. The lantern was for a good idea, the cube was for help in solving a tough problem, and the football was for going the extra mile. Every month the person who had received an award would then pass it with the appropriate specific praise to another person. This is a fabulous and light way to recognize people, and it contributes to team identity.

There are the usual corporate reward programs, and you should leverage whatever tools you have available. Sometimes the corporate awards are bigger formal awards, and sometimes it is possible to get money for “light” awards like gift certificates that can be handed out when you or others catch someone doing something special. Another activity that can be powerful is to make it a point to reward or recognize those who are friends of user experience. As they move up in the company and prosper they may have even more influence in creating a great work environment for user experience people and helping you prosper. Remember it is not just the big formal award; it can be just as powerful to take a moment to say a sincere thanks and to be explicit about what we are thankful for that makes a difference. I have to say that I have been fortunate to have had members of my team over the years who even occasionally give me a pat on the back. During a recent round of organizational changes, for example, I was feeling some stress and was not my usual self. I cannot tell you how important it was to me when I came into my office and found a card on my desk from a member of my team with a word of encouragement.

What makes a great work environment for designers and user researchers? People certainly want growth and growth opportunities. In many engineering environments user experience people feel a glass ceiling that is hard to get through. They see paths for project managers and engineers all the way up to the highest levels in the corporation, but often they do not see the same path for user experience. Many go into management because they see that as the only way to continue to grow and reach higher levels of reward, or they may move into other disciplines such as project management where there seem to be more possibilities. Movement to grow skills in new areas of interest is great, and it is a wonderful way to drive more design thinking through the entire corporation, but you would like to avoid having people move because they do not see any other opportunities. One of the values of having higher level user experience people at the VP and CEO levels is that it provides an example of what might be possible. You can help create an effective UX program by getting involved in shaping the rules used to evaluate performance and support growth.

Moving Through the Growth Cycle

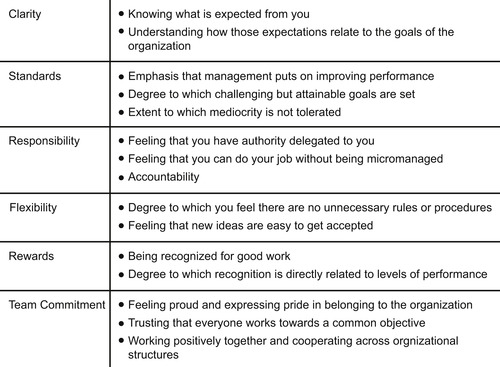

A fairly common model of team formation is shown in Fig. 6.3. The first stage in the model is forming. This is when the team first comes together with your first hires, or when your team undergoes major changes (e.g., a reorganization or a rapid period of hiring). Everyone is a relative stranger (including the manager), and everyone’s strengths and weaknesses are unknown. Everyone wants to make a great impression right away, wants to be assigned to work they will enjoy, and wants to start showing success. Some handle this by becoming hyper-conservative, and others handle it by becoming hyper-assertive. The team may feel more impersonal, people may be a little guarded and dependent, and some slowly feel their way into a situation while others jump in heedless of impact.

|

| Figure 6.3 Team formation model. |

Your role as the leader in these early days is to be more directive in leadership style, perhaps more than you are used to or are comfortable with. The idea is to clarify roles and responsibilities quickly, and assign who is doing what. Get everyone focused on a set of goals and objectives, and show progress toward those goals. Be more hands-on and keep up on what is happening and provide lots of guidance. Keep communication flowing. You do not know what everyone can do, so you want to learn as you work with team members and help them to learn from each other. Start to bring people together by building out the strategic framework, clarifying the common purpose and values of the team, establishing operational norms and policies, and working together to define your vision and mission.

Pretty quickly the team is likely to move into the storming stage. My experience is that as individuals start to get grounded in their space, they want to start really showing what they can do. Since the members of your team do not completely understand their peers yet, they get frustrated when others (who in turn are trying to establish themselves) do not yield to their will and seem to get in the way. They sometimes forget to share what is on their minds, so other team members see them as loose cannons. The team becomes like a dysfunctional family, confronting and blaming as communication breaks down. People may rebel against you and against each other, some may try to seize control from you or from each other, and others may simply react in an emotional counterproductive way.

The manager needs to become the therapist and provide a directive (to keep the team moving forward) and supportive style. I have found that if values of openness and communication were established up front, you can leverage those to bring people together; avoid assigning blame; and just get conflicts and disagreements out in the open with an attitude of “We’re in this together. How do we move this forward?” It is important to give lots of feedback both on what you like and what you want to see happen. You want to give each member of the team a sense of where they are succeeding so they understand what success looks like, that they are getting the visibility and recognition that they desire, and that they are on the right track. But you also want to end the superstitious and counterproductive behaviors that cause misunderstanding and problems. This is probably not the time to overreach; instead it is the time to help team members become successful as they focus on the tasks at hand. Extra steps to connect people at a human level can be important during this time — morale events, time working on joint projects together as a team, and so on. This is a good time to get people laughing together.

The norming stage is when people are settled into their jobs and they begin to understand each other. I liken it to the time after I had been married for a few years or a friendship that is deepening. You understand what you like about the other people on the team and know how to work around what annoys you about them, and they understand your unique strengths and weaknesses and how to deal with them. You begin to understand what team members are going to do in different situations, and they understand what you are going to do. You have a personal connection with others on the team, and appreciate and enjoy much of its diversity. When conflicts happen, and they do, there is a habit of getting them resolved early rather than late, and it is relatively straightforward to get most resolved. At this stage people are clearer on their respective roles, and they are more open to feedback. The team has found ways to communicate reasonably effectively, and the team identity is starting to form — there is team cohesion.

As a UX manager or lead in this stage you can do more coaching and be less directive. You see who you can trust to really run with their jobs and who takes a little more engagement. You also see how the team is working, and are able to help them grow to independence as they build knowledge and skills. It is a time to refresh the strategic framework, and to start introducing some of those big bets and big challenges that further grow the team together and begin to really establish your unique brand — your unique mark on the organization. More and more leadership is delegated to members of the team, and you are able to drive your own initiatives while working on unblocking and supporting the team. You are providing a supportive leadership style.

The final stage (some models include a further excelling stage, but I see that as part of this final one) is called performing. A team that is performing is like a well-run professional kitchen or a sports team that is really clicking. Everyone has the same goal, but everyone knows their individual roles and responsibilities. They do their jobs, but are able to adapt as circumstances change and as others have to adjust to the circumstances. There are often multiple interdependencies, but nobody is dropping the ball, or if they do someone else is there to pick it up. The team is focused on the goal. They trust each other, they are committed to the team goals and each other, and they are open. They are interdependent and support one another, and you see real collaboration. Think about a design team that has been in this stage. The image is often a group huddled around whiteboards doing a lot of sketching, talking, and creating. There is always plenty of laughter. Ideas spontaneously pop up, and people pull together to make things happen.

This is the stage that brings the greatest joy for many managers, because now you can really challenge and grow the team. You are reinforcing what you like, but you are also moving the bar higher and engaging the team to collaborate in achieving the higher bar. You want to stay out of the way, but not disappear. The team is successful when you do not need to be there, but it is better when you are. You challenge individuals and the team as a whole. This is when you can drive big bets and the results inspire and transform organizations. Even better, members of the team on their own initiative are doing things that exceed your expectations but align with your dreams.

It is frustrating that whenever you go through a major change such as when people are added, an organizational change such as layoffs, or something else significant, the team can go all the way back to the forming stage. The good thing working in your favor is that at least some of the team has been through this before, so the rails are already laid to move more quickly through the stages. You probably need to harness your experienced people to help you help the new ones understand what they are experiencing and how to embrace it.

Managing Through Change

Everything is in a state of flux, including the status quo.

Robert Byrne

I have been through major changes at several points in my career. One of the most stressful was when I was at Ameritech and the first waves of layoffs were going through the industry. Many people who had assumed they would have lifetime employment suddenly were finding themselves out of work. At one company a manager was shot and there were bomb threats at the job site. After the layoffs there was survivor’s guilt, and while the company was completely reinventing itself the organization needed to adjust to missing people who had been part of the family. A milder change, but one that still added stress to the management role, was when my team moved to a new organization and doubled in size within a month, and then more recently moved again, had layoffs, grew again, and then completely changed in how it was funded. In our industry, the norm is change. Managing through change often requires you to go back to the forming stage in the growth cycle. Sometimes it is traumatic; sometimes it is exciting.

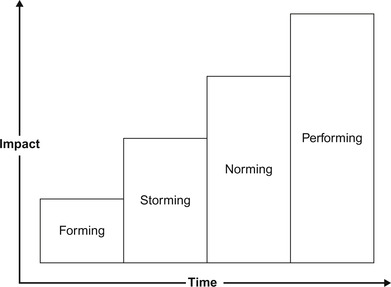

I have noticed that the best description of the emotions people tend to go through during change is well-represented by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ (1969) grief cycle shown in Fig. 6.4.

|

| Figure 6.4 The grief cycle. |

This experience is typically triggered when the change is unexpected. A fair criticism — but one that it is hard to avoid — is that if people had known what was coming they might not experience the change in quite this way. Changes that the UX manager is driving can and should involve the team, and people can move through the stages very quickly. But changes that senior management is driving and where decisions must be made without involving the team typically cause members of the team to experience most if not all the stages of the grief cycle.

When people feel the changes are hitting them unexpectedly, it is the unexpected nature that is the problem and they feel powerless. The core to helping people through the process is to help them regain a sense of structure, predictability, and control. Building on that structure, the goal is to re-engage people in a positive vision that will motivate them. To do that, one of the best techniques is to engage them in refreshing the vision and mission of the team. With my Windows Server System team, when we made the changes, we set up an offsite and began by explicitly presenting this grief cycle and recognizing that the feelings were normal. We then divided into the new teams, and the new teams began to work on reinventing their vision and mission statements and bonding around the leadership of their new managers. That approach seemed to work well. When my current team doubled in size, we began by gathering at an offsite and started to build out our strategic framework (especially identifying the shared values, roughing in the elements of a vision, and starting to build a mission statement).

As the changes at US West Advanced Technologies started during the acquisition by Qwest, the company leveraged guidance from change management consultants Price Pritchett and Ron Pound. They identified a variety of principles useful in helping people reacquire a sense of structure and control, and how to focus them on the future. These (fairly self-evident principles) include:

• Keep a positive attitude.

• Take charge.

• Set a clear agenda. Give your troops clear-cut marching orders. Focus on short-range objectives, and establish clear priorities. Nail down each person’s job, roles, and responsibilities. Focus on hard results rather than intangibles.

• Pay attention to process.

• Promise change … and sell it (carefully).

• Get resistance to change out in the open.

• Raise the bar. Show a sense of urgency.

• Encourage risk taking and initiative. Motivate to the hilt.

• Create a supportive work environment. Spend freely with “soft currency.”

• “Ride close herd” on transition and change. (I found this means spending more than the usual amount of time one-on-one with people listening and seeing where people are in the curve and supporting them.)

• Rebuild morale. (This is a good time to crank up the pats on the back.)

• “Beef up” communications efforts.

• Go looking for bad news.

• Re-recruit your good people.

• Take care of the “me” issues in a hurry. Play the role of managerial therapist.

• Be supportive of higher management. (Do it by finding what you can support, and being candid and honest about your own feelings and how you are working through them.)

• Be more than a manager … be a LEADER.

Winning Loyalty

The secret of managing is to keep the guys who hate you away from the guys who are undecided.

Casey Stengel

Creating team loyalty begins with being a leader rather than a manager. The goal is to be the kind of person that people want to follow and to create loyalty, rather than just relying on the formal designation of manager. At a workshop on ROI at the Usability Professionals Association (UPA) one year, the representative from Intuit talked about loyalty as a metric. Customer loyalty is another step beyond customer satisfaction. It is satisfaction that is so great that the customer is willing to put their own reputation on the line by recommending the product or service to one of their friends. Employee loyalty is similar. It is a willingness to follow that is so great they are willing to recommend you and your team to their friends and colleagues. Your own employees are recruiting on your behalf everywhere they go and pulling others with them as they try to follow you.

To get at that kind of loyalty there are a few additional principles that build on the standard leadership principles. First, genuinely care about each individual. For myself, I try to explicitly and implicitly establish a kind of contract with each individual who joins my team. I do not expect people to work for me forever, and I will not hold them forever. I will “compete” to deserve their loyalty and their best efforts by working to grow them further than anyone else, to help them be successful, and to help them get rewarded to the maximum extent possible for their work. I will work to remove barriers for them and to do everything I can to create a great working environment. I will try to match their interests and passions with what I need to get done. In return I expect them to give their best while they work for me, just as I am giving my best to them. If the time comes when they have grown beyond the team and their role, or if someone has lured them away with a situation better than I can offer, then we will part friends and colleagues. Indeed, I will help them get there.

It is important to be genuine. A nice phrase is “listen hard, talk straight.” There is also “practicing what you preach.” Living the values you believe and express is the place to start. You want to be as honest and transparent as you can. There are times you cannot share everything because of the constraints you are under in a given situation, but try to share everything you think people will want and need to know. Also make it clear where the boundaries are on what you can answer and why.

Finally, make sure you are rewarding success and shaping the right behaviors. Catch people doing the right thing, and recognize and reward it. When something is happening that is clearly bad and going to hurt, catch those things early. Talk them through with the person and describe the behavior you want to see, then recognize and reward that person as they work to get there. In conditioning theories, punishment has a tendency to generate random behavior whereas positive reinforcement has the ability to focus behavior. I have found it works for teams in the workplace and not just in the laboratory.

Identify Shared Values

Trust takes a lot of moxie and commitment to build. It takes a long time, and you can lose it overnight.

Max DePree

Values are the beliefs that are shared by the team. They are at the heart of the emerging culture of your team, and when articulated provide rules of collaboration to help resolve conflicts. Right after I doubled my team in size, we were back in the team formation stage. There was already feedback that people were reporting misunderstandings in their conversation, mistrust of motives, and other communication issues. Worse, people were struggling with how they could resolve the issues. A lot of people were coming to me to “fix” the problem with the other person (by implication, to whip them into shape). I laid the groundwork for dealing with this by getting everyone on the same page about the values we all agreed on and what we wanted as the rules of engaging one another. This was one of the techniques I adapted from the Sapient culture. At Sapient we used it to get workshops off on the right foot.

I set the workshop up simply as wanting to identify the shared values we wanted to use as we interacted with each other and the teams with whom we work. We began by throwing out individual words and thoughts. Some of the words stimulated people to talk about things that mattered to them such as what it means to grow in trust of another, what respect means, and so on. After collecting all the words and phrases, we clustered them to find the key words that captured the big thoughts. We eventually got to a list that we all agreed were the shared values. After the offsite, I then started thinking about how we could represent the core ideas that we were talking about and how we wanted to work together as a team. I wanted to avoid the traditional sports metaphors, and thought back to successful team building experiences. One, which I describe in the section describing morale events (Chapter 7), was the experience in a gourmet kitchen. I found a picture of such a kitchen and created a poster (Fig. 6.5). We posted them around the team spaces.

|

| Figure 6.5 Team values. |

In subsequent one-on-ones and sessions working with team members struggling with how to work together we were able to draw on the shared values. I could point to the values that we all agreed on, and begin with the understanding of the common goals. We could then brainstorm about solutions to the conflicts that were consistent with exercising the values. I was also able to set up metrics and goals in terms of the values, and to build growth in relevant values within the team commitments.

Clarity in Roles and Responsibilities

RACI

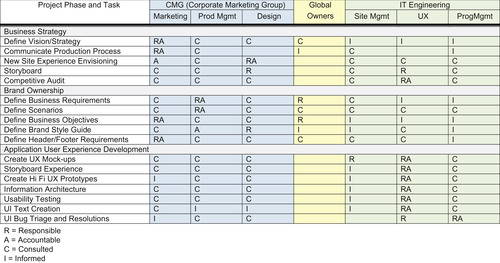

One of the common themes woven throughout the discussions of how to put an effective user experience team together, how to resolve conflict, how to manage through change, and how to collaborate across discipline boundaries is to reach clarity on roles and responsibilities. There are a variety of tools to do this. Within my current organization, the tool of choice is the RACI matrix, also known as the Responsibility Assignment Matrix or the Linear Responsibility Chart. There are variations on the classic RACI based on additional roles to be assigned and there are variations on the approach (e.g., the OARP, the owner, accountable, responsible and participant).

In our organization, the R in RACI is the person who is responsible. People who fall into this category do the work to achieve the task. In some organizations there is only one R, and others assist in supporting roles; in other organizations there can be many Rs taking responsibility for different portions of the overall project. The A is the person who is accountable. There should only be one person who is on the line to make sure the task or deliverable is completed. This may be the person who signs off that the work that the R person or persons have done is complete and acceptable, or it may be a person who is both the A and the R for a project. There are also C people. These people are consulted and their opinions are sought. They do not have veto power. Their input is not mandatory, but it is carefully considered and incorporated. It is a good practice to ensure that they understand how their input was used (or not) and why. Finally, there are the people who are kept informed. This is typically just one-way communication.

RACI is just a tool to add clarity. An RACI can be defined for how various disciplines and organizations should work together through the course of a software development project (see Fig. 6.6). It lists all the deliverables that make up a typical project, and assigns the appropriate roles to each person for each deliverable. When I joined the IT organization, one of the early projects I was part of included going through the existing process, integrating user-centered design into it, and then redefining the RACI to include user experience.

|

| Figure 6.6 RACI example. |

Another way we have used RACI is to resolve interorganizational conflict between collaborating UX teams. There is a user experience team in corporate marketing responsible for branding, which supports the marketing organization in its definition of the design direction they would like key areas of the corporation to head. My team, on the other hand, is responsible for the detailed design of many of these areas, and is in the organization creating the platform and common design patterns across the site. We negotiated an RACI to help clarify how we will work together across our respective organizations and through the process. Starting the project by laying out the principles and getting senior management sign-off, and then drawing out the implications within the RACI, has made it easier to collaborate effectively. When our respective designers bump up against each other, we both can pull out the RACI as a way of resolving the differences. The third way we have used this tool is to clarify roles and responsibilities within the user experience team itself, especially where there are several people working together on a project (and indeed when there are several people leading different aspects of the project such as research, design, and overall planning).

Gavin S. Lew

Managing Director, User Centric, Inc., Chicago, IL

How do you train someone to be a user researcher or designer? In most cases it starts with formal education. Professors usually do a good job teaching information architecture, design, and user research principles. But in the end, that’s all theory. In reality, much of what we do cannot be learned in school. Success in the user experience field depends on understanding subtleties and perspectives that are very hard to teach, yet make the difference between a good researcher and a great one. At times researchers may do something in a way that goes against personal logic, but makes sense with an understanding of overriding priorities, the client’s greater objectives, or our relationship with the client. The challenge comes in figuring out how to teach those nuances to individuals on a team. This is why we have implemented a mentoring/apprenticeship model.

When a person joins our team, he or she is assigned a mentor. The mentor’s first role is showing the ropes to a new person, answering administrative questions, and generally helping that individual become acclimated. As the new person begins working alongside a mentor on projects, he or she begins picking up on the important subtleties of user research. The mentor provides anything from general guidance to help with specific tasks, and may give input regarding performance and career advancement. The mentor pairs have quarterly lunches to talk about progress and personal development. The mentor also gives feedback to management, so we’re aware of where consultants may need help, and can determine how to place consultants on projects where they need more experience (or have a special area of interest).

Most mentor relationships continue for at least a year, and mentors may change on a yearly basis. But our feeling is that no one ever really outgrows the need for a mentor. Even our senior people have said they need mentors to keep growing. This tells me the system works, and is valuable. Forging these kinds of cooperative relationships with the support of upper management strengthens the whole team. Everyone becomes better in an environment where they can openly share their expertise and readily learn from others. Mentorship fosters just this kind of cooperative interaction and continuing growth.

The mentoring program is also an attractive selling point in recruiting new researchers and designers. I emphasize to applicants that we don’t expect them to know everything. We want them to come in with a willingness to learn how to apply what they already know, and to fill in gaps in their knowledge as they work alongside more experienced consultants. This fosters organic growth, which is always best in an organization. When you can bring people in with the right background, then give them the growth opportunities they need, the whole organization will be stronger as they take more responsibility and move forward in their careers. Mentorship is one of the keys to making this happen.

Organic growth is also made possible through internships and apprenticeships. Many of our senior and management staff began as interns or apprentices. Bringing someone in for a three-month commitment enables us to learn whether they have the intellect and the capacity to do what we need them to do. In turn, they can learn about our work and whether they like it here. If it’s a mutually good fit, we may hire them. We’ve found great success with this model; half of our company has been built on organic growth. Some people who’ve come in through internships during graduate school have risen to director positions within ten years.

However, there are only certain economies that will support apprenticeships and internships. When the market is booming and demand is high, people may not want to take the risk of quitting one job to take a three-month contract. On the other hand, when the market is poor and there is less opportunity, there’s much less risk involved and short-term opportunities become more attractive. There are times and places for different practices. Often, we find ourselves locked into a practice. Adapting to the changing workplace will ensure that you have the most appropriate positions to secure top talent.

Finding and training the right people is never easy, but internships, apprenticeships, and a good mentor program have made a big difference for our company. We’re able to hire the right people, train them in more effective ways, and enable everyone to benefit as they learn from each other’s strengths and grow together.

Natalia Kirillova

Managing Partner, Business Development Director, UIDesign Group, Moscow, Russia

My company was founded in 2003 when there was still no usability market in Russia. One of the main problems we faced was that nobody knew what usability was and why customers would need our services. We have carried out a major effort to establish the market, to educate it and to move it forward. Eventually, when the business started to grow, we encountered another problem that was even more difficult to solve. There were no trained professionals around. Today there are still no educational programs in usability, user experience, user centered or interactive design in Russia. Lacking qualified resources is even more painful because the market is growing.

The only solution is training the staff ourselves. My story will look very familiar to companies in young UX markets. Mature markets have similar issues. Our discipline is complex, dynamic and developing. A good UX consultant should be equipped with knowledge, experience and skills related to how technology works, and how to talk to users and elicit requirements. This person has to know user research techniques and when each of them is to be applied. He or she needs to have a good grasp of visual design, as well as decent communication and prototyping skills. They should be a broad-minded person who can consult onsite. Today UX services come together with search engine optimization, marketing, web analytics and other areas. How do you obtain these “golden” brains and hands?

We started training and teaching in 2004, when we decided to assign a mentor to every new employee in the project. The particular feature of this method is that the mentors assign tasks and then do not leave the trainees alone for a long time. The trainees are supposed to work under the direction of their mentors in order to learn how the professionals deal with different issues. To track the progress in mastering new skills and acquiring experience, it is good to have a list of personal competencies for every trainee, and to regularly update the record with the types of projects and work completed. Learning from a user experience mentor reminds me of other professional fields where creativity plays a significant role, like painting, cooking or any other art or handicraft. To obtain the full skills of a chef, an apprentice has to observe the master’s work for a long time. That is how a new master can be created.

Though practice means a lot, it is not enough. Practice should be supported by the theory. There are several ways to train professional skills and advance knowledge. They should be offered in an appropriate combination for the individual (defined by a mentor depending on a trainee’s personality):

1. Internal and external seminars and workshops provide a chance to apply theory and sometimes include practice.

2. Books and articles give fundamental theory.

3. Authentic blogs and news help to keep a trainee up to date.

4. Activities such as conferences and participation in professional societies provide the state of the art.

The careful application of these activities gives an opportunity not only to learn, but also to discuss and exchange opinions with colleagues. It helps them to develop a personal opinion on different issues and to broaden their horizons. This is crucial for a mature consultant. Besides professional knowledge and experience, working in the user experience field requires accuracy, curiosity, self-discipline, creativity and many others. Some of them, such as creativity, are possible to train, but it takes a lot of time. I belong to those who believe that creativity is a skill and is not simply an inborn talent. Everybody can become a creative thinker when trained using techniques such as brainstorming, brain writing, mind mapping, and storyboarding.

Gavin S. Lew

Managing Director, User Centric, Inc., Chicago, IL

If a team is going to be highly productive and functional, leaders need to understand the dynamic presented by having different generations working alongside one another. Even though our company’s two principles are a Baby Boomer and a Generation X-er, our company was recently named one of the Top 50 Generation Y Employers in Chicago. Why? We recognize that Generation Y has different needs, and we try to understand and adapt to them, rather than succumbing to the irritation and aggravation that can prevail in multigenerational work environments.

One way to understand the differences in these groups is by looking at advancement. Baby Boomers came of age in a work environment where if you stayed with a company a certain length of time, you would be promoted. This was accepted, and even if someone excelled at work, there was an understanding of “doing one’s time.” The Boomer generation shared a set of ideals, rules formed around those ideals, and people followed the rules.

Generation X came along, and while they focused more on relationships and their personal rights and skills in the workplace, they understood the legacy of the Baby Boomers. The ideals and rules, while not embraced by the Gen X-ers, were (perhaps grudgingly) accepted. This group was more individualistic, and while they might have looked for ways to have more control over their career advancement, they still played by the rules the Boomers had laid out.

Generation Y, on the other hand, grew up in a high-tech world, and they expect things to happen at a different pace than the Boomers or Gen X. Short attention spans may have started with Generation X, but they became a given with Gen Y. The Boomers’ mentality of “Wait seven years and something good will happen” will not fly with Gen Y. They need something happening — whether it’s advancement, a title change, or some kind of ego boost — every 18 months. Gen Y-ers also feel entitled to praise — they were, after all, raised in an era where everyone on a team got a trophy. They need to feel valued and sense that they’re moving forward. Rather than facing this as a frustration, the wise employer will recognize that Generation Y is a smart, technology wise, and flexible generation. If we’re willing to re-tool our approach, we can better capitalize on their strengths.

Successfully working with Generation Y also requires a different way of communicating than Boomers and Gen X-ers are used to. Gen Y individuals need to be given very explicit directions and descriptions. Here’s an example (which actually happened at our company): An urgent matter arose late one afternoon, and the Baby Boomer said, “I need help with this; it needs to be done as soon as possible.” The Generation X employee buckled down immediately and worked late. The Generation Y employee left at 5:00 p.m., without notifying anyone. He had plans that night, and figured that getting the project done in the morning would be “as soon as possible.” This wasn’t negligence, but rather was a reflection of the Gen Y employee’s need for a clear definition of the time frame. (He also needed to be told to check in before leaving, something a Boomer would think was second nature. Not so with Generation Y.)

Generation Y doesn’t understand the definitions and principles and ideals that Boomers take for granted (and Generation X picked up on due to proximity). This doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with any of these groups. They just work and communicate differently, with different expectations. Managers need to recognize this fact and adapt to it, because it’s reality. Struggling with it will cause unnecessary frustration, but handling the differences with wisdom and understanding can catapult a team to new levels of productivity and success.

Tharon W. Howard

Director, Clemson Usability Testing Facility, Clemson University, Clemson, SC

I like to think of the “stuff” my teams create as a by-product of good communication between members. The real product of a team is communication; anything else the team creates — like a new interface design or a research study — is just gravy. So if communication is the sine qua non of team building, then my job as a team manager is creating the conditions that allow members to communicate with each other as successfully as possible. However, the problem with a new team or a new member on a team is that people have different communication needs and different styles of communicating, and when new members don’t understand those needs or styles, miscommunication, misunderstandings, and dissention can occur.

One technique I’ve used successfully to deal with this is to use DISC profiling with new teams. Based on the work of William Moulton Marston and his 1928 book, The Emotions of Normal People, DISC was one of the earliest psychometric instruments created, and like the famous Myers-Briggs personality type indicator, DISC classifies people’s psychological traits using four different quadrants and scores them based on how people respond to a series of statements and word associations. DISC is an acronym that describes each quadrant.

D = Dominance: People who score high “D” tend to communicate very directly and forcefully; they value visionary thinking and problem solving, but don’t like a lot of details and can get annoyed when people don’t get directly to the point.

S = Steadiness: People who score high in this area value stability and loyalty. They dislike communication that will “rock the boat” and are annoyed by “mission creep.” They often have to be drawn into a discussion and prefer to listen carefully and then find points of agreement.

C = Conscientiousness: People who score high in this quadrant value logical presentation, accuracy, and clarity of expectations. They are annoyed by communication that is overly emotional and doesn’t “stick to the rules” or pay close attention to protocol.

The way I use DISC with new teams is to contract with Inscape Publishing or one of the several vendors who offer online versions of the DISC instrument and then have all the members take the test and obtain their reports. Then we meet as a group in a comfortable location and we talk about what we’ve each learned about our own communication styles and needs. In order to keep this from becoming too personal or to keep people from focusing entirely on the negative aspects of the different communication styles, we start off by having the team brainstorm about famous leaders who fit each category — Gandhi was probably an “S,” Jimmy Carter was probably an “I,” and so on. Basically, I try to generate a list of people the team respects who exemplify each DISC quadrant so that members recognize that each style offers value as well as limitations. However, asking the team to figure out whether Teddy Roosevelt was a D or an I makes it possible to talk about how people have elements of all four quadrants, and no one should be “pigeon-holed” as a D. This is an important point to make with your team because one of the dangers I’ve discovered with using this approach is that people will often try to use the information in their DISC profile reports to attempt to excuse inappropriate behaviors. They’ll say, for example, “You just have to deal with the fact that I’m a C, and we’re gonna play by the rules here.”

I try to teach my teams that they can’t allow themselves to make this sort of statement since, ultimately, the goal is to realize that “playing by the rules” is a blind spot for both Ss and Cs. It’s a crutch they use when they’re under pressure, but what they need to do in order to become more successful communicators is to find ways to build up their D and I qualities. Their DISC profile is not a clinical measure of who they are and always will be; rather, it’s merely a description of their particular communication tendencies at that moment. However, those tendencies can change.

I have to confess that I’ve had mixed success at getting everyone on a team to buy into the idea that they have blind spots and that they weren’t born a D and can’t change who they are. It’s also a technique that only works well one or two times since repeating the DISC profile with the same members gets stale after the third time. Nevertheless, I can report that using DISC with new teams certainly does get them sharing information about their communication styles and needs, and it does make them more tolerant of their differences. Naturally, they still get annoyed with one another, but they do communicate with each other faster and more effectively, and since my job is to facilitate that communication, that’s a positive result I can accept.

Gavin S. Lew

Managing Director, User Centric, Inc., Chicago, IL

As the person who’s in charge of personnel at our small company, I noticed that many of our human resources policies — which are intended to solve or prevent problems — were actually causing more confusion. After our office manager would implement a new HR policy, I would end up spending an inordinate amount of time answering questions.

As a solution, we began issuing a statement of rationale along with each new human resources policy. Since every policy emerges because of some rationale, we decided it made sense to give people the rationale along with the policy. When given the reasons — from a business perspective — for a policy, most people understand the rationale and fall in line. Of course there will always be individuals who just don’t like rules, but even they do better with this system, because they get the thinking behind it, rather than just having a rule laid on them. If someone has ideas about approaching a matter differently, we’re open to their suggestions. We make it known that we’ll listen to anyone’s input as long as his or her proposed solution considers our rationale.

Since explaining the reason behind policy decisions is so important, we actually spend more time on the underlying principle than the rule when introducing a new policy. This is more difficult than it seems as it requires discipline to provide rationale as new employees come on board. Thus, documenting is essential. We also continue reminding people of the rationale as time goes on. This has alleviated many issues by empowering people to think through things themselves. When questions come up about defining sick time, working from home, etc., there’s no need to quote a rule. People who understand the rationale will make better judgments and come to sound conclusions on their own without being held to the rule of law. When coupled with a mentor or apprenticeship program as described [insert citation], communication can be extremely clear and create a community that supports policies.

As an example, let’s look at our Work From Home (WFH) policy. At User Centric, we recognize that the need for flexibility is paramount to having a well-functioning and productive team, but this is nothing new. Flexibility is different from a permanent WFH schedule that individual employees negotiate. This policy is for those instances where we need to support life’s everyday challenges or to make employees more productive while working on a specific project. So, we made a special WFH option to be used by request.

We thought this policy made sense. Employees found it to be very useful. We asked that employees e-mail at least 24 hours in advance to WFH and that they had sufficient work to do. In our history, we never turned a WFH request down, but then we started to get requests that appeared to be somewhat suspicious. In one example, one employee made a request in the late afternoon for WFH the following day. Basically, the workload to be performed at home was to catch up on e-mail and expenses. We thought that these activities tended to not fill a full business day, so we asked questions and quickly realized that the request was due to a lack of transportation that was known about a week prior.

Our subsequent discussion focused on the fact that the transportation issue was known well in advance and the workload did not represent a full day’s work. The employee said that there was not much work to do, so working from home seemed to make sense. Our response was that had we been aware of the issue, we could have assigned work to be performed. The rationale behind the WFH policy is to allow flexibility but to also allow a full day’s work to be performed, or personal time if warranted. If there is nothing to do then we would like employees to speak up, as there are areas where more effort is needed or fellow team members could use support.

Issuing rationale statements also helps smooth the implementation of new policies by mitigating fears about something new. It may answer questions before they even arise, and assure staff that things are happening for good, well-thought-out reasons. Our intention is to provide for independence and allow for flexibility. We need to improve communication between HR management and individual work effort. While putting new human resource policies in place can be a minefield, we’ve found that simply being up front with a sound, clearly communicated rationale prevents problems, saves time answering unnecessary questions, and fosters better communication overall.

Tim Bosenick

Managing Director, SirValUse Consulting GmbH, Hamburg, Germany

In the year 2000, when I founded SirValUse in Hamburg, Germany, it was my aim to build a small but effective UX research and testing company in 10 years with approximately 12 employees. This clearly failed. Since the beginning of 2010 the SirValUse-Group employs approximately 100 people, and is one of the largest UX research and testing companies in Europe, and I am more tied up in “managing” than anything else.

One of the biggest challenges in this growth process was, and still is, to maintain the quality of our work. Especially between the years 2003 to 2006, when we doubled our sales yearly, many new colleagues started to work at SirValUse with little experience in the relevant areas. This is all tied up with the fact that UX/UCD is a relatively young discipline in Germany and only a few universities offer a relevant education, especially in the fields of “research” and “testing.”

So in 2004 it was our task to incorporate as many new colleagues as fast as possible, but our clients expected our accustomed quality. “Quality” was and will be important to us on two different levels: on one hand it means “quality of process,” and on the other it means “quality of results.” An important aspect of process quality for us was to get the new colleagues familiarized with the standard processes so they would be able to carry out those standard processes independently. These processes concern all phases of a project, from preparing a screener for recruitement and the session guide and performing the session itself, to the analysis of data and the report. The quality of results build on the analysis of the test object and the contents of the screener and the session guide, as well as depth of analysis, arrangement and presentation of the report, and the development of recommendations.

In a first step to help as we added new colleagues, a group of experienced members of the team defined the standards and guidelines for process and performance quality. This process wasn’t that easy because of different practices even between teams. During many meetings and sometimes contentious debates we defined these standards and were finally able to document them in a binding agreement. This process took place from the end of 2003 until early 2004. Afterwards the team worked out a teaching and qualification plan to bring the new colleagues closer to the developed quality standards. The quality measures were coordinated with the management and the HR departments. To make this happen one of the most experienced colleagues was freed from project work to work exclusively on this task.

The training and qualification plan consisted of the following components:

1. Support of exchange in connection of concrete project work

2. Formal qualification measures

3. Accompanied project coaching measures

1. Support of exchange in connection of concrete project work

To support the exchange between colleagues, two approaches were taken.: The complete company was divided into three (later four) teams based on SirValUse relevant branches. The result was that members of one team can work on similar themes and questions and acquire experience in these sectors. One approach to exchanging information is that all team members meet weekly for approximately one hour to discuss projects and discuss methods and results. Problems from one project can be avoided on other future projects.

Another approach to exchanging information is that after the weekly company meeting a project member presents a fascinating 30-minute project from the last 3 months. The focus is mainly on an exciting “best practice” aspect of this project, both methodological and in terms of results. The aim of the event is to transfer learning across the teams and to discuss measures and examples, making it clear how they drive the quality of results.

2. Formal qualification measures

We have determined the following themes as formal qualifications:

• Communication with clients

• Project kickoff, proposal, calculation, briefing

• Project organization

• Running international projects

• Moderate sessions

• Documentation of sessions

• Analysis and interpretation of data

• Creating the report

• Documentation of projects

• Usability and user experience basics

• Usability and user experience methods

• Cross-cultural usability and user experience testing

3. Accompanied project coaching measures

In the middle of 2006 we invented accompanying project measures. Our quality manager collaborated with the personnel manager to develop a coaching plan. The coaching plan included general aspects that repeat and/or sharpen single items of formal qualification measures. All this is broken down into the specific coaching needs of single colleagues.

The essential idea of coaching is to coach in conjunction with real projects, thereby concrete problems of colleagues are adopted and one can learn on the job. With the high involvement of the colleagues we achieved a deeper awareness of learning.

Finally, internal qualification measures were completed with external quality guidelines. For example, at least once a year our external service providers run through a quality feedback. Within our international network UXa (user experience alliance; www.uxalliance.com) occurs mutual feedback after every project and our clients are asked for concrete project feedback regularly. All of the external feedback has in turn influenced internal qualification measures planned for next year.

I am pretty happy and proud in retrospect that we created this “quality offensive” from both direct and indirect acknowledgments from our clients. Also our colleagues are more motivated by the feedback and time the company provides for quality measures.

Tharon W. Howard

Director, Clemson Usability Testing Facility, Clemson University, Clemson, SC

Teams have life cycles; like people, they go through stages of development. I’ve found that when members don’t understand those stages and then encounter misunderstandings and dissention the result is that the team shuts down and stops functioning. To avoid this problem, I train my teams to use Bruce Tuchman’s theory of team development to talk to each other about where they are as a team.

Tuchman was a social psychologist who worked for the U.S. Navy. His job was to try to identify what characteristics of small group dynamics would lead to successful unit performance. To investigate this question, Tuchman conducted a meta-analysis of 50 different research studies that psychoanalyzed small groups. His research identified four distinctive phases.

• Forming: During this initial phase, team members obey social protocols of polite behavior in order to communicate with each other. They try to use social conventions in order to minimize conflicts and to get along with one another until they learn more about other team members and their roles in the group.

• Storming: This is an extremely important and necessary phase of a team’s development, and it’s the point where differences in interpretations of the team’s mission, the scope of the project, means of measuring successful completion criteria, descriptions of each member’s role on the team, and other disputable issues emerge. The term “storming” doesn’t mean that teams have to suffer acrimonious and agonistic debates, but it does mean that there are questions and issues that have to be resolved before the team can move to the next phase.

• Norming: The group reaches some form of agreement about issues raised during the storming phase and begins working out practices and procedures for functioning together and for making collective decisions. During this phase, teams agree on the “rules of the game” and how they will collaborate.

• Performing: During this phase, team members share a common vision and understanding of what constitutes success. They have shared protocols and procedures to which they all adhere, and because they have learned to trust each other, they are able to function autonomously and without overt supervision.

One of the things I try to communicate to my staff about Tuchman’s model is that it’s an iterative model, which is to say that a team can get knocked out of the performing stage and sent back to the storming phase at any time. A new team member, changes in upper management, funding reallocations, new technologies, and many other factors can require that a team renegotiate all of its understandings. More importantly, however, I try to help my staff understand that “storming” isn’t a bad thing and that they avoid storming at their peril. High-performing teams often need to go through long periods of storming to learn to trust each other and to become successful.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.