Chapter 13

Delivering Services through Crowdsourcing

The spread of social media and other technologies continues to empower non-state actors and increase the connections between seemingly disparate populations. Accelerated connectivity is producing conditions where poor standards of living and oppressive lifestyles in one part of the world can produce ideologies and epidemics that can cause catastrophe in other parts. The norms and arguments that define global security are shifting with the realities of contemporary global connectivity. Thus, in some cases, the provision of adequate education and health services is becoming critical to ensuring security and stability. The link between health and security is even more pronounced and apparent. Today, social media technologies can enable the provision of such services in areas where they are critical to ensuring security but are nonexistent or crippled for various reasons. This chapter explores how you can use social media to deliver educational and health services in remote parts of the world.

Delivering Education

Inadequate access to education, especially for girls in rural areas, can severely damage a population's health and security.1 Major powers such as the United States consider increasing global access to mainstream education important to maintaining global security and are, therefore, undertaking efforts to build schools and provide school materials in poor, dangerous, and denied areas. Also, they wish to push back against education that poor children in some areas typically receive, which can be incomplete, in dangerous conditions, and more focused on inoculating children with a certain ideology. However, such efforts are hard to sustain over the long term because they are expensive and difficult to execute.2 Emerging countries such as Indonesia also wish to increase access to education to their rural and poor populations to sustain their development. They are dedicating enormous parts of the economy to providing educational services, but still do not have the resources to deliver education to their entire population in a traditional manner, which requires school buildings, teachers, and books.3

Fortunately, social media technologies can provide educational services to denied populations in an innovative and cost-effective manner. As we discussed in Chapter 2, the use of mobile phones and SMS technology is widespread in even the most rural areas. In the following sections, we discuss two methods by which you can leverage this existing mobile phone use, inexpensive tablet computers, and crowdsourcing mechanisms to deliver education to children in the most remote areas. Delivering education through social media also enables you to collect intelligence about the perceptions of local populations. We address the side-benefits of a social media–based education provision later. However, before we detail the two methods, we need to explore some new research and considerations that will help you structure an education provision through social media.

Understanding How People Learn

In the past decade, academics and non-governmental organizations have tried novel ways of educating children in urban and rural areas using a variety of technologies. Their efforts have illustrated how cheap and readily available social media technologies can provide education, and illuminated the conditions under which children and people, in general, learn best. (From now on, we refer to children as opposed to all people because the findings are more pronounced in children due to of the elasticity of their brains; however, they still relate to all people, including adults.) Some of their findings are surprising, counterintuitive, and go against traditional notions and methods of education. You need to understand their key findings so you know which methods work best and what results you should expect. We do not get into detail about the findings or how they came about—this is not a chapter about education. We only summarize the findings so you can use social media effectively and in a way that is aligned with human behavior. You may find that some of the insights about how people learn may help you better structure influence platforms with other objectives. The key findings are that children learn better when:4

- They are placed in groups of four to five and encouraged to learn educational material together. Children do not need sustained individual attention from teachers. Instead, when in groups, children can teach each other and help each other comprehend difficult or complex parts of the material even in a language they do not fully understand.

- They can go at their own pace and choose subjects that interest them. Everyone learns different information at different rates. Also, they are more likely to pay attention and expend the mental effort to learn something if it interests rather than bores them.

- Information is delivered through metaphors and stories. As discussed in Chapter 11, people do not always pay attention to rational arguments and objective facts. Metaphors and stories possess emotional content that attracts attention and utilizes shortcuts to deliver complicated information, which makes it more likely that an individual will remember and adopt the information.

- Moderators, who are not necessarily full-time, trained teachers encourage children and praise their learning. The encouragement can be as simple as leaving a message saying they are doing a good job.

- The educational material is directly relevant to the children's daily lives. Children are more likely to educate themselves, and their families are more likely to let them, if it is apparent that the material they are learning will teach them vital skills that will boost their family's income. The time anyone spends on education is time they do not spend working and supporting their family. Thus, the immediate economic utility of education must be apparent.

- Rote memorization of facts is replaced by interactive material that focuses more on problem solving and teaching the perceptions, frames, and viewpoints a person can use to make sense of the world. In the age of Google, human brains need not waste effort remembering facts that the Internet can recall for them in a moment's notice. Instead, they need to focus on using the facts and other information creatively to produce an innovative solution to a problem. This is as relevant in the design offices of Apple as it is in the farmlands of Indonesia.

- Gaming elements, some of which we explored throughout Part III of the book, are integrated into the educational material and are used to deliver the material. Integrating gaming elements in education can involve creating a simple math game that children can play on dumb phones that, for example, gives them points for getting multiplication questions right. In certain cases, especially when children are involved, gaming elements can introduce competition and motivate children to work harder to beat their peers. Games also enable you to quantify and track a child's performance over time. Additionally, just as children are more willing to take medicine if it is packaged as a sweet candy, they are more willing to learn material if it is packaged as an educational game. Another benefit of games is that children are willing to play them over and over again. As we discussed in Chapter 11, repetition improves information adoption. Lastly, in some cases, children can actually play a part in creating educational games. Creating such games improves the children's retention of the educational material. By enabling children to create games, you also end up crowdsourcing educational material and games that you can then provide to others.

Another key finding, and one that is most relevant to you, is that technology can play a significant positive role in delivering educational services. Specifically, existing and emerging social media technologies can help deliver educational material, track progress, and modulate coursework as required. Next, we describe the two methods by which you can use social media technologies to deliver education in denied areas. Many more methods exist, but these are the easiest to implement today. The first method is relatively more complex and expensive to implement but more comprehensive, and the second is simpler and cheaper but not as powerful. Still, both methods are much cheaper and, in cases involving poor, hard-to-reach populations, more effective than the traditional education method of building schools, printing and distributing textbooks, and employing full-time teachers.

Building crowdsourcing platforms to deliver services involves following the same process we detailed in Chapter 8. You can even label the platforms to deliver educational and health services that we describe in this chapter as service platforms. However, to focus on the most distinguishing elements of the platforms and to keep from being repetitive, we will not describe the service platforms in the same structure and format as we described the other platforms in Part III. Instead of going over the process of analyzing the target audience or marketing the platform, we simply focus on how you can design the platform. Assume for both methods that the target audience is a small population of young children in a rural and poor village in a large, developing country such as Indonesia where dumb phone use is widespread although not ubiquitous.

Delivering Education through Tablets and Mobile Phones (First Method)

The first method involves providing inexpensive tablets and dumb phones to children in the area to deliver educational content and track overall and individual performance. Before we detail the design of the platform, we first describe the tablets and mobile phones involved.

Overview of the Tablets and Phones

We briefly covered the different types of tablet computers in Chapter 2. Most popular tablets such as the iPad or Kindle are expensive and provide numerous features, some of which are quite complex and powerful. The tablets we refer to in this section are much more inexpensive and have fewer features, although they still are impressive machines. Such tablets include the UbiSlate tablets (known as Aakash tablets in India) that are priced at around $35–$60 USD and currently are being supplied to Indian schoolchildren. UbiSlate tablets come in two types: the UbiSlate7 and the UbiSlate7+. We focus on the latter tablet, which has slightly more features. (Check the website at www.ubislate.com for the most updated price and feature information.)

The tablets run Google's Android operating system and feature a sufficient amount of memory and power. They enable users to log on to the Internet through either Wi-Fi or cell network connectivity much like an iPad with 3G connectivity or an iPhone. The tablets have a built-in battery that users can charge using a variety of methods, including small, portable solar kits. The tablets are built using special material that makes them durable and able to withstand abuse by children. In all, the tablets are not that different from more powerful Android tablets widely available in the West. Users can use UbiSlate tablets to surf the Internet, play games, read documents, take pictures, make phone calls, watch videos, and listen to music.

The mobile phones are typical dumb phones, the kind that most Westerners used before the advent of the iPhone and smartphones. The dumb phones typically used in developing countries are manufactured by Nokia and enable the user to make and receive phone calls, send text messages, and play a few simple games. Some dumb phones also feature the ability to surf the Internet using a special browser. Dumb phones are fairly inexpensive and widely available in almost every part of the world. Our target audience may have a few dumb phones, which they usually charge by paying a person in their village who possesses a charging station, also known as reliable electricity.

The Process of Using the Tablets and Phones

The tablets and phones both possess certain content and enable the participant, who in this case is a child, to receive educational services. Assume the target audience consists of fifty children, all part of a small village with some access to electricity. A few families may possess dumb phones, but generally the use of social media technology is low.

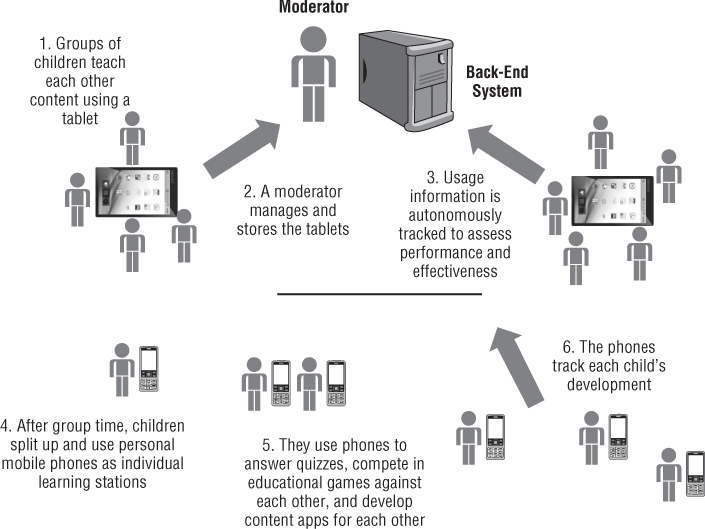

You need to build a service platform made up of tablets, phones, and a back-end system that manages the data. The overall process is that groups of children use the tablets together to review and learn educational material. They then use the phones individually to take tests and receive feedback. The children also use the tablets and phones to create and share educational content with their peers. The back-end system tracks how the children use the tablets and phones, the content on the devices, and the performance and feedback of each child.

First, you need to purchase five tablets and load them with educational content. Each tablet focuses on a specific subject such as math or biology. Educational content can include anything from screenshots of textbooks, to videos of lectures, to simple applications and games that help children learn some basic concept. Free repositories of such content already exist—examples include Khan Academy (http://www.khanacademy.org) and PhD Gaming (http://www.phdgaming.com). You can update the information on the tablets remotely because they will have Internet connectivity through the cell network. To enable Internet access for the tablets, you need to purchase and install a prepaid SIM card in each tablet so they can access the local cell network.

Designate either a local village person or a person from your organization as the moderator for the village. If the person is a member of the community, you may need to incentivize him by providing him with a dumb phone to use. The moderator will take care of the tablets and oversee the program for you. Give the tablets to the moderator, along with an ability to charge the tablets. In some cases, providing the moderator with the ability to charge things might be incentive enough.

The moderator is primarily responsible for maintaining and storing the tablets and handing them to groups of four to five children. The tablets rotate through multiple groups over the course of a week or day. The children access the educational content on the tablets as they wish, albeit with a little structure and help from the moderators. As we discussed in the education findings, children are remarkable at teaching themselves and each other various subjects, often regardless of the difficulty of the content. The children can also use the tablets to create educational content including games and quizzes, which you can collect through the tablet's Internet connectivity. You can also program the tablets to collect information about exactly which group is accessing the tablet at a given time, what they are doing with it, and how they are using it. After group time, the children return the tablet to the moderator.

The children then use the dumb phones as their individual learning station. Some families in the area likely have dumb phones, but you may need to provide others with one. Each family thus possesses a dumb phone with ample incentive to maintain it and ensure that their children can use it. You can tell the families that they are allowed to use the phones for other things only if they ensure that their children get to use it for two hours a day. Equip each phone with simple educational content, including simple games, and a prepaid SIM card that connects the phone to the cell network. When the phone has access to the cell network, you can also enable it to remotely download new and updated content and games.

The children use the phone to review some of the content they learned during group tablet time at their own pace. They also use the phone to respond to blast SMS quizzes that test their retention of the content. See Figure 13.1 for a picture of an example SMS quiz.

Figure 13.1 SMS quiz example

Remember that you can track which child is using which tablet and for what. You can also track which phone belongs to which child's family and how they are using it. You can program both the tablet and phone to regularly and automatically upload information and usage metrics to your data management system. Using the same connectivity, you can also frequently update the tablets and phones and the content on it. The moderator also needs to keep track of who is using what device. Because you can track which child is using which tablet and phone, you can make sure that the child receives an SMS quiz to her phone that pertains to what she reviewed on the tablet. The data management system can track the child's response and thus also track her performance and educational content retention. Moderators and volunteers from around the world can also text message the child every once in a while and provide her with encouragement and solicit feedback. For cases where families have multiple children, you can either provide multiple phones or simply ask each child to respond with their name. Your moderator can also ensure that each device is collecting information about the correct child. The information you collect does not have to be perfect or that individualized. You simply need an idea about how children in the village are doing overall and whether the trends of retention and performance are positive. Lastly, the children can also use the phones to text each other questions and create games that they share with their peers. The moderator can reward the children for creating and sharing games and content. You may need to integrate services such as GroupSMS (http://www.grouptext .info) that enable users to mass text a group of people. This way, the group of children who review a tablet together can also send each other text messages about what they have reviewed or quiz each other without bothering the other groups. See Figure 13.2 for a graphical overview of this method.

Figure 13.2 Tablet and phone method overview

Over time, as the method grows in acceptance and popularity, you likely need to scale up your efforts to more villages. Because you are crowdsourcing content and games from children throughout, you can then send the same content and games to other children. In this way, your educational content will become refined and more relevant and applicable to your target audience. The children will start teaching the other children digitally in the most austere parts of the world for a fraction of the cost and effort without requiring school buildings, outdated textbooks, or full-time teachers.

Delivering Education through Mobile Phones Only (Second Method)

The first method involves purchasing and distributing both tablets and phones, which can get expensive and, in some cases, may be hard to manage. The second method reduces the cost and complexity involved by distributing only dumb phones to children to deliver educational content and test their performance. The second method is similar to the first method in many ways, but the focus is solely on the phones.

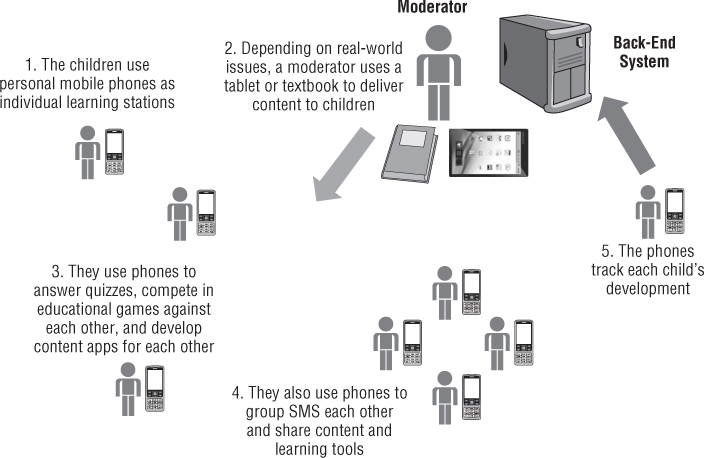

You still need to designate a moderator for the village, and purchase the same type of dumb phones with prepaid SIM cards. The key difference is that you need to preload the phones with more educational content. You may need to provide the moderator with books or a single tablet that he can regularly distribute and use to supplement the content.

Each child's family receives a phone that the child uses as an individual learning station. Depending on conditions on the ground, the moderator provides books or a single tablet to rotating groups of children. The groups of children also review the content on their phones together. The children then receive blast SMS quizzes on their phones and encouragement from the moderator and volunteers, and send out responses, feedback, and share content with others. The data management system and the moderator track the performance of each child by regularly and automatically collecting various usage metrics from the phone. See Figure 13.3 for a graphical overview of this method.

Figure 13.3 Phone method overview

Compared to the first method, the amount of content you deliver to children will be smaller through the second method. You also need to be more creative about how you package the content for a device with a small interface, memory, and processing power. Still, the second method provides educational content and tracks overall performance much more effectively than the lack of any educational service or a haphazard and infrequent one. Unlike schools that often shut down and reopen, with the second method, the children will at least always interact with updated educational content.

Side-Benefits of Delivering Education

A service platform not only enables you to deliver humanitarian services, but it also enables you to use the platform as an intelligence collection, solution, or influence platform. The social media technologies and crowdsourcing techniques involved in service platforms are the same as in other platforms. A participant with a dumb phone can use it to educate himself, provide you with intelligence and solutions, or engage with others about their views and willingness to engage in certain behaviors. By providing phones to families, you are also expanding the size and diversity of your target audience. You can even encourage or mandate the adults in the family to use the phones for regularly providing you with intelligence about illicit activity in their region. Also, take note that when you are providing education to children, you are also influencing them and their families. The content they learn can significantly alter how they view the world. You are also improving their views of you because you are openly helping them by providing them with a critical service that will improve their lives. Additionally, asking children to create and distribute educational games that their peers will like is no different from asking participants to submit solutions to complex problems.

As you become more experienced with crowdsourcing, expect to deploy platforms with multiple diverse objectives. Doing so will incentivize the target audience to participate and can help obscure more sensitive objectives. Use one type of platform, such as a service platform, to incentivize participants to participate in another type of platform, such as the intelligence collection platform. Meanwhile, you need not advertise that you want participants to join a platform to provide you with intelligence. You can simply advertise that you are encouraging participants to join so they can receive a service, and only then make it known that a condition of receiving the service is also providing intelligence.

You can also use one service platform to deliver multiple services, including health services as we describe next. By using the same technology for multiple purposes, you are saving enormous amounts of money and making it easy for the target audience to engage with you on a number of levels, help themselves, and help you.

Delivering Health

When we refer to delivering health services, we do not primarily mean delivering medicine, although social media can help amplify medicine delivery efforts. Instead, we refer to delivering health-related services such as the ability to diagnose individual disorders based on symptoms, collect aggregate information about health problems in an area to track epidemics, and provide updated and critical health and safety information to populations.

The link between health and security is more obvious and immediate than between education and security. Because of this link and other reasons, a significant amount of money and effort has been spent on delivering health services through social media technologies. A number of organizations have deployed health services platforms, also known as mobile health or mHealth projects and applications. The platforms typically deliver two types of services. The first type helps users figure out what ails them and provides a diagnosis. The second type collects and aggregates medical information about many users for various purposes. Some combine the two types.

However, many such platforms are unsustainable for various reasons, stymied by regulations, or not applicable for poorer and more denied populations. They typically focus on expanding health services in the Western world. They require their users to have Internet access through either computers or their smartphones. Although such health services may not appear directly relevant to your needs, you still need to know about them. You can adapt the services for access via dumb phones, and as smartphones and Internet access become more widely available, many developing regions will gain the ability to access similar services. If you can deliver such services, you will drastically improve the health of the populations and prevent catastrophic epidemics. In the subsequent sections, we review some of the platforms by their type and briefly describe how you can adapt them to deliver basic health services to denied areas and improve the health and security of populations globally.

Diagnosing Health Problems

Virtual diagnostic platforms or applications are becoming widespread because they are relatively easy to make and deploy. A popular example of a diagnostic service is WebMD's symptom checker, which is available at http://symptoms .webmd.com. When first accessing the service, a user plugs in some basic demographic information about herself such as her age. The user then identifies various symptoms from which she might be suffering. As the user selects symptoms from the list, the service reasons about what ailments the user may be suffering from and presents them in a list. As the user picks and refines her symptoms, the list of ailments decreases until only a few remain. Finally, the service presents the user with the ailment she likely suffers from according to the information she provided, and also provides information about her ailment. The user then has an idea of how and why she is sick and what she needs to do about it.

Other virtual symptom checker and diagnostic services also exist. An Android application and website named Symcat, available at http://symcat.com, works similarly. Different diagnostic services primarily differ in the algorithms they use to figure out a diagnosis for the user, and the data they use to train their algorithms.

Problems with Existing Diagnostic Services

Diagnostic services are mostly available in the Western world for Western populations, and they are not always applicable for populations in developing regions. They create algorithms based on data collected in Western hospitals about Western populations, and thus are more adept at understanding the symptoms and diagnosing the ailments that people in rich, developed countries typically suffer. Also, they design the interface of their applications in such a way that the applications only work on computers and smartphones. For example, WebMD's symptom checker enables users to click on parts of a diagram of a body to indicate where on the body they are suffering pain or discomfort. A user with a dumb phone that has only SMS messaging capability cannot use such an interface.

Lastly, assessing the accuracy and precision of diagnostic services is difficult, which is not a critical issue for most Western diagnostic service users. Many people who use such services likely do it for ailments that are not very serious, like colds and the flu. If they do it and find out they have something more serious, they have the option of going to a doctor to get a proper diagnosis. People in developing regions are regularly threatened by much more serious diseases such as malaria and do not always have the option of going to a doctor to get an accurate diagnosis and treatment. A mobile diagnostic service would be a significant help for people in areas denied of traditional diagnostic services. Upon learning of his condition, a person in rural Africa may not be able to visit a clinic, but he may be able to still acquire generic drugs or take some simple precautions that could save his life or prevent the spread of his disease. Fortunately, adapting such applications for dumb phones and less wealthy populations is not difficult.

Adapting a Diagnostic Service for Denied Areas

We are currently designing and hope to soon deploy a symptom checker and diagnostic service that populations in developing regions can access through their dumb phones and SMS. You can deploy a similar service, albeit with a little effort. The service has three parts: the algorithms, the data management system, and the SMS interface.

First, create the algorithms that can understand the symptoms and demographic information of people in a developing region, and use that information to diagnose them. Creating and refining the algorithms is arguably the most difficult and technologically intensive part. Various data modeling tools and methodologies can help you create and train the algorithms to ensure they can adequately diagnose a person based on their symptoms and demographic information, including their location (some ailments are more likely to occur in certain areas). You will likely need to work with healthcare and data modeling organizations to create the appropriate algorithm.

After creating the algorithms, you need to create a robust data management system that houses the data you collect from users, runs the algorithm on the data, and then sends the user the diagnosis. The system is the lynchpin of the service platform and helps you coordinate and combine the different parts of the platform.

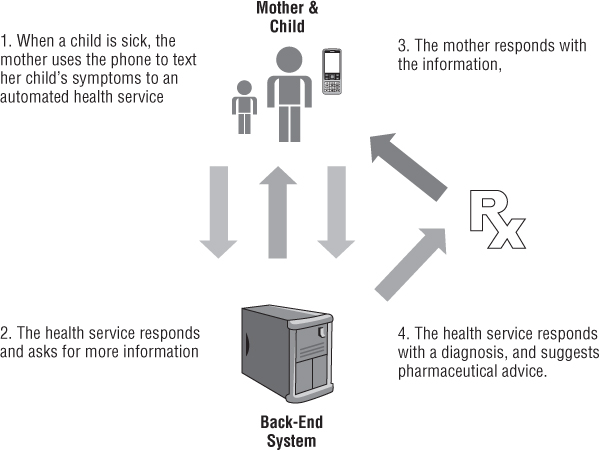

The third and final part involves enabling people in denied areas to interact with your data management system and submit data to it so it can process it and respond back with a diagnosis. Essentially, the user sends an SMS message to the system, via a shortcode, containing her symptoms in a specific format. The system responds automatically with a text message asking for more information. After the user has submitted enough information, the system texts back a diagnosis to the user. The service can also suggest pharmaceutical advice and coordinate delivery of drugs, if appropriate. Figure 13.4 provides a graphical representation of the diagnostic service process.

Figure 13.4 Diagnostic service for denied areas' process

Ideally, you need to create the algorithms in such a way that they can offer diagnoses by using only a little bit of user-submitted information. People in developing regions likely do not want to spend a lot of money sending text messages to your service platform. One way to improve the diagnostic process and collect more information from users without compelling them to send more text messages is to use physical diagnostic tools. Various organizations are working on small tools that you can connect to dumb phones and smartphones that can, for example, measure blood sugar levels.5 You may be able to partner with an non-governmental organization in an area, who sends out a facilitator armed with a physical mobile diagnostic tool that regularly measures some critical information about people in the area. The facilitator can then provide the information to the user who texts it to your system.

You may have noticed that you are simply collecting a form of intelligence from people in denied areas. As discussed at the end of the education section, you can use the information you collect for a variety of reasons. You can use it to refine and improve your algorithms and to track the spread of disease in an area. The next section briefly describes how you can collect intelligence about various health indicators and analyze it to identify and track epidemics and other health events of concern.

Collecting Health Information

Numerous service platforms collect the health information of people for various purposes. They collect information using different methods and for different purposes. Many collect aggregate information about a population to track the spread of epidemics, which we focus on here. You can also easily collect information from populations in denied areas to figure out if they are suffering from diseases, how those diseases are spreading over time, and if you need to be concerned about it.

Existing Health Information Collection Services

One of the most popular examples of such a service is Google Flu Trends, which you can access at http://google.org/flutrends/. Google Flu Trends uses an ingenious but simple method of semantic analysis to figure out how flu is spreading over time in various countries around the world. Google simply keeps track of how many times and when a person in a certain area uses Google's search engine to search for terms related to flu and influenza. Google assumes that people will search for information about the flu if they have the flu. If a lot of people in an area are searching for information about the flu, then lots of people in the area likely have the flu, and so the flu is spreading. Google counts the number of times people in an area search for flu-related terms and figures out if, at a given moment in time, a lot of people in a specific area are searching for things related to the flu. Google can then figure out where and at what rate the flu is spreading at any given time. According to studies cited on its website, Google Flu Trends is fairly accurate.

Other services collect much more detailed and personal information about a person's health. They actively seek out people and ask them about their health. They either ask the person and/or store the information using social media technologies. Many such services focus on collecting health information in hard-to-reach, rural, and poor areas. A quick search on the Internet will easily reveal several.

We have already covered some of the technologies and platforms these organizations use to collect data. For instance, the FrontlineSMS software community released a version of its software now known as Medic Mobile (http:// medicmobile.org) and previously known as FrontlineSMS:Medic. Medic Mobile's website features several tools that anyone can download and use to collect health information. Another example of a technology that we have covered and is relevant to collect health information is crowdmaps. You can see an example of a crowdmap that encourages people to text in information about health and other related items at https://smsinaction.crowdmap.com.

Unfortunately, for various reasons either much of the information these services collect goes unused or the services do not collect enough information for it to be useful. One reason is that the organizations and individuals behind the services simply do not know what to do with the information. The organizations collecting the data are typically non-profits that are either wary about turning over their data to companies and governments or are willing to share the data but do not have the right contacts. Another reason is that the various organizations do not coordinate data collection and so end up repeating a few projects. They either collect data about one area over and over again or they only collect data about one item. Some even haphazardly collect data without paying attention to consistency and reliability. Assessing the validity of their data is difficult.

Two other reasons have to do with the problem of approaching issues in poor regions with the same mindset as approaching issues in Western, developed regions. The first reason concerns the issue of privacy. People in the West typically are wary about sharing personal health information with others, especially organizations that they do not know. Although many Westerners do not have access to health services, many in the West still have the luxury of being picky about with whom they share data. People in poor regions that are likely rampant with disease do not have that luxury, and so are not as concerned about privacy. In many cases, they are willing to share information with others as long as it can help them and their families. Some organizations are understandably but needlessly too concerned about privacy in such regions. Thus, they collect incomplete data that is not useful. The second reason concerns the issue of regulations. Western government organizations stipulate exactly how health services should function, including health information collection, and often for good reason. However, some do not seem to realize that such regulations do not exist in other parts of the world and that they can try out things they would not be allowed to try in the West. They artificially limit the types of services they launch and the type of data they collect. Of course, some will abuse the lack of regulations and cause problems. However, we see it as a blessing in disguise that enables you and others to deliver health services in ingenious ways to areas that desperately need them.

Adapting Health Information Collection Services

With knowledge about what types of services exist and their problems, you can easily adapt and create new services to collect information about people's health around the world. You can then create an epidemic tracker and early-warning system. You can also use the same mobile health information collection tools to collect health data from forward deployed units.

You can easily adapt existing health information collection services to serve your needs. The easiest way is to combine and analyze various health data sources to create your own version of Google Flu Trends that looks at trends of other health problems. You can create a semantic analysis tool that, for example, counts how many times people in a certain location tweet or text about a certain illness or symptom. You can then figure out if a disease is prevalent and spreading in a certain area. Creating such a tool is relatively simple.

To get the data, you need to search the Internet for existing data sources and build your own intelligence collection platform. First, search the Internet, news sites, and the Medic Mobile site for services that provide data about people's health issues. Also check out data feeds from the World Health Organization's website (http://www.who.int/research/). Although news and data feeds will be slightly delayed over those gleaned from social media or SMS, they offer important validation for the other data you collect via social media and your own intelligence collection platform. Also, consider partnering with local organizations that regularly collect health data from local populations. By combining the various sources, not only will your accuracy be higher, but your practice at using the different technologies will improve as well.

If enough data does not exist for your region, you may need to create an intelligence platform. The platform should incentivize participants to periodically submit information about their health. We already discussed one such incentive—provide them with an ability to diagnose their ailment. You can create your own platforms using a variety of methods, many of which we discussed in previous chapters. We encourage you to use a combination. Ideally, you should use the types of tools available at Medic Mobile to create a local or directed version of your own platform just to test it out in its entirety. The tools are free other than the cost of text messages, and a broad support community exists to assist in fixing bugs and other issues you might have along the way for your first iteration. Once you've ensured that you can get everything to work, you can use that same deployment for medical use as well as other uses.

After acquiring the data, build a simple semantic analysis tool such as the one we described before to analyze mentions of symptoms. Of course, this is easier said than done. In practice, properly creating appropriate analytical tools will be somewhat difficult and require creativity. You have lots of ways to analyze the health data to track the spread of disease. You can do spatial analysis to see the spread of disease over physical space, and therefore can simply plot the mention of symptoms on a map (such as with Ushahidi's crowdmaps). You can also do temporal analysis to see the spread of disease over time by using a simple spreadsheet program that tracks the mention of a symptom along with when it was written. Better yet, you can combine the two types of analyses and create a tool that shows the spread of disease over space and time. Some tools will do this for you, such as Google Earth, ARCGIS, and even crowdmaps. Ideally, you should design your own interface for the most flexibility and analytical power. Real-time information feeding into such a system could easily be the most advanced platform for looking at diseases in the past and in real time. To take it to the next level, you could even use software such as the type created by Recorded Future (available at https://www.recordedfuture.com) that attempt to extract “future events” from the Internet. Simply put, they take a tweet that says “Cholera will hit Zimbabwe in two weeks,” reason that cholera may occur in Zimbabwe in two weeks, and then map it temporally. ">that attempt to extract “future events” from the Internet. Simply put, they take a tweet that says “Cholera will hit Zimbabwe in two weeks,” reason that cholera may occur in Zimbabwe in two weeks, and then map it temporally.

To create an even more robust system, you could bring in past data and do comparisons to your real-time data. You can then test the validity of your analytics. You can also compare the health information you collect with information that measures the existence of other events such as famines, food shortages, and migration. You can then identify correlations between seemingly disparate events and forecast the spread of epidemics with much more fidelity. All this may sound impossible, but it is not beyond the current technical capabilities. It only requires coordination, motivation, and some ingenuity.

As you read this chapter, you may have concerns about the implications of collecting and using information that people typically consider private. Chapter 14 considers the implications of privacy, and how you can use the techniques without infringing on people's privacy and right to freely express themselves."/> considers the implications of privacy, and how you can use the techniques without infringing on people's privacy and right to freely express themselves.

Summary

- You can use social media technologies and crowdsourcing techniques to deliver humanitarian and other services that are integral to security.

- Social media can inexpensively and effectively provide educational services to populations in denied areas.

- Through a combination of inexpensive tablet devices and dumb phones, you can provide education to young people in rural, poor areas.

- You can use crowdsourcing platforms that provide education to complete other objectives such as collect intelligence.

- You can use crowdsourcing techniques to collect information from participants about their symptoms, and use the symptoms to provide them with a diagnosis, all through text messages.

- You can also use crowdsourcing techniques to collect information about the health of populations in remote areas to track epidemics over space and time.

Notes

1. Oxfam International (2011) High Stakes: Girl's Education in Afghanistan. Accessed: 3 October 2012. http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/afghanistan-girls-education-022411.pdf

2. Winthrop, R. and Graff, C. (2010) Beyond Madrasas. Brookings Institution. Accessed: 4 October 2012. http://www.brookings.edu/∼/media/research/files/papers/2010/6/pakistan%20education%20winthrop/06_pakistan_education_winthrop.pdf; United Nations (2010) Millennium Development Goals. United Nations Summit. Accessed: 4 October 2012. http://www .un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG_FS_2_EN.pdf

3. ACDP Indonesia (2010) 2010-2014 Ministry of National Education Strategic Plan. Accessed: 3 October 2012. http://www.acdp-indonesia.org/files/attach/MoNE_Strategic_Plan_2010-2014.pdf

4. Gee, J. P. (2007) What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York; Mitra, S. (2010) “The Child-Driven Education.” TED. Accessed: 3 October 2012. http://www.ted.com/talks/sugata_mitra_the_child_driven_education.html; Robinson, K. (2011) Out of Minds: Learning to be Creative. Courier Westford, MA, USA.

5. Bettex, M. (2010) “In the World: Health Care in the Palm of a Hand.” MIT News. Accessed: 4 October 2012. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2010/itw-sana-0927.html