CHAPTER 7

Using the Camera

In the hands of even a moderately skilled photographer who knows the capabilities of the camera, even a cell phone can produce reasonable pictures. Unfortunately, owning a camera and knowing which button to push doesn’t make you a photographer, any more than owning an automobile makes you a Formula One racecar driver.

—Andy Ciddor, TV Technology

Today’s cameras can create high-quality images. With the right techniques, you can produce interesting and persuasive images. A working knowledge of the camera, lenses, depth of field, shutters, and f-stops is essential to obtain images with the maximum impact.

Key Terms

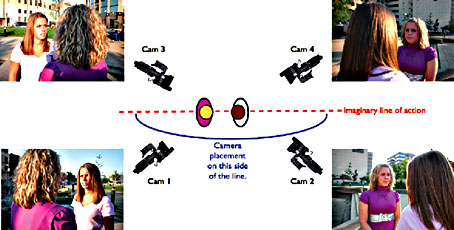

![]() Action line: Also known as an eye line, the 180 line, or the proscenium line, this is the line along the direction of the action in a scene. It is the line that separates the “stage” from the audience. Cameras should only shoot from one side of this line.

Action line: Also known as an eye line, the 180 line, or the proscenium line, this is the line along the direction of the action in a scene. It is the line that separates the “stage” from the audience. Cameras should only shoot from one side of this line.

![]() Auto-focus: Some lenses are designed to automatically focus on the subject.

Auto-focus: Some lenses are designed to automatically focus on the subject.

![]() Backlight control: When there is more light in the background than on the subject, some cameras use a backlight control button, which opens up the iris an arbitrary stop or so above the auto-iris setting to improve the subject’s exposure.

Backlight control: When there is more light in the background than on the subject, some cameras use a backlight control button, which opens up the iris an arbitrary stop or so above the auto-iris setting to improve the subject’s exposure.

![]() Black-stretch control: Some cameras include a black-stretch control menu or button that can be adjusted to make shadow detail clearer and improve tonal gradation in darker tones.

Black-stretch control: Some cameras include a black-stretch control menu or button that can be adjusted to make shadow detail clearer and improve tonal gradation in darker tones.

![]() Close-up shot: Encourages the audience to concentrate on a specific feature. Shows emotion on people and draws the viewer’s attention to a detail/aspect/ portion of an object.

Close-up shot: Encourages the audience to concentrate on a specific feature. Shows emotion on people and draws the viewer’s attention to a detail/aspect/ portion of an object.

![]() Follow focus: This technique requires the camera operator to continually change the focus as the camera follows the action.

Follow focus: This technique requires the camera operator to continually change the focus as the camera follows the action.

![]() Long shot or wide-angle shot: Helps establish the scene for the viewer.

Long shot or wide-angle shot: Helps establish the scene for the viewer.

![]() Macro: Some lenses include a macro setting, which is designed to provide a sharp image almost up to the actual lens surface.

Macro: Some lenses include a macro setting, which is designed to provide a sharp image almost up to the actual lens surface.

![]() Medium shot: The medium shot tells the story; it is close enough to show the emotion of the scene but far enough away to show some of the relevant context of the event. Generally shot from the waist up on a person.

Medium shot: The medium shot tells the story; it is close enough to show the emotion of the scene but far enough away to show some of the relevant context of the event. Generally shot from the waist up on a person.

![]() Pan shot: When the camera pivots to the left or right with the camera pivoting on a camera mount.

Pan shot: When the camera pivots to the left or right with the camera pivoting on a camera mount.

![]() Telephoto lens: A narrow-angle lens that gives a magnified view of the scene, making it appear closer.

Telephoto lens: A narrow-angle lens that gives a magnified view of the scene, making it appear closer.

![]() Tilt shot: When the camera pivots up or down on a camera mount.

Tilt shot: When the camera pivots up or down on a camera mount.

![]() Waveform monitor: An oscilloscope that displays a fluctuating line that traces the variations of the video signal, the sync pulses, and so forth. Individual picture lines can be selected and examined. Its several uses include checking for exposure errors, ensuring that the video does not exceed the system’s limits, and checking the accuracy of sync pulses.

Waveform monitor: An oscilloscope that displays a fluctuating line that traces the variations of the video signal, the sync pulses, and so forth. Individual picture lines can be selected and examined. Its several uses include checking for exposure errors, ensuring that the video does not exceed the system’s limits, and checking the accuracy of sync pulses.

![]() Wide-angle lens: Shows us a greater area of the scene than is normal. The subject looks unusually distant.

Wide-angle lens: Shows us a greater area of the scene than is normal. The subject looks unusually distant.

![]() Zone focus: Camera operators are focused on a portion of the scene. Any time the subject comes into that area, the camera has been prefocused to make sure the action is sharp.

Zone focus: Camera operators are focused on a portion of the scene. Any time the subject comes into that area, the camera has been prefocused to make sure the action is sharp.

7.1 JUST POINT AND SHOOT

Many people just point and shoot. They assume that the camera should be set on automatic, and therefore they don’t worry about it. There are times when the automatic setting is the way to go. However, most of the time the results will be disappointing. The exposure may be incorrect, the auto-iris may fluctuate, and the subject may be blurry. Many times the shots are just plain boring. The audience’s attention will wander and the picture quality varies. That’s unfortunate, considering that by mastering a few basic principles, effective images can be created that look professional.

7.2 WHAT GETS ON THE SCREEN?

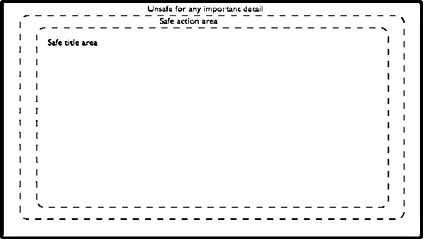

Occasionally, the camera is described as the “eye of the audience.” However, that can be a misleading oversimplification. The camera can be used to deliberately create that impression, but the camera doesn’t automatically convey a true picture of any situation to the audience. If individuals are at a location, their eyes flick around, refocusing, taking in what is happening. They know where they are and can decide for themselves what they look at. Everyone makes his or her own selection from a scene. Television viewers can only see what the director chooses to show them. Only that part of the scene selected by the lens is visible on the rectangular screen in front of them. The audience can only guess at what lies outside the lens’s angle of view. Other things quite near the camera would fill the screen if the lens turned just a little, but these things remain unseen, “out of shot,” because framing is highly selective (Figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1

The camera isolates. The camera only shows what is going on in its frame of the scene. The audience does not really know what is outside the field of view.

(Photo by Josh Taber.)

A hallmark of good directors is their ability to select from moment to moment exactly the right features within the scene that suit their dramatic purpose, yet at the same time convince their audience that this is exactly what they want to see at that instant.

7.3 HOW CLOSE SHOULD YOU GET?

![]() A close-up shot (CU) is great for revealing detail, intimacy, emotion, and drama. Sometimes it can even reveal too much: It encourages the audience to concentrate on a specific feature.

A close-up shot (CU) is great for revealing detail, intimacy, emotion, and drama. Sometimes it can even reveal too much: It encourages the audience to concentrate on a specific feature.

![]() Keep in mind that restricting how much the viewers can see might frustrate them, particularly if they feel that they are missing something going on elsewhere.

Keep in mind that restricting how much the viewers can see might frustrate them, particularly if they feel that they are missing something going on elsewhere.

Be careful not to throw details at the audience too blatantly as if to say, “Pay attention! Look at these details!” Good production techniques are based on persuasion. There are many subtle ways of influencing exactly where your audience looks, without throwing out intense close-ups all the time. You can persuade with images by controlling the way the composition is arranged, such as by moving people around or positioning the lighting.

A long shot, or wide shot, shows the audience a wide view of the scene:

![]() It establishes the scene by showing the audience where the action is located.

It establishes the scene by showing the audience where the action is located.

![]() It lets viewers see how one thing relates to another (such as the various relationships between team members on a basketball team).

It lets viewers see how one thing relates to another (such as the various relationships between team members on a basketball team).

![]() It can give them a good idea of space, unless the director deliberately misleads them by using a much wider lens angle than normal to exaggerate perspective.

It can give them a good idea of space, unless the director deliberately misleads them by using a much wider lens angle than normal to exaggerate perspective.

An overall view of this type does have its disadvantages. Although HD helps this situation, the audience may not be able to see subject details clearly in a wide shot. The viewer can see the speed with which the player runs after the ball, but not the expression when he or she drops it (Figure 7.2).

CAMERA SHOTS

![]() Extreme close-up (ECU or XCU) or big close-up (BCU) is a detail shot.

Extreme close-up (ECU or XCU) or big close-up (BCU) is a detail shot.

![]() Close-up (CU) is generally framed just above the head to the upper chest. This shot is sometimes called a “head and shoulders” shot.

Close-up (CU) is generally framed just above the head to the upper chest. This shot is sometimes called a “head and shoulders” shot.

![]() Medium shot or midshot (MS) cuts the body just below or above the waist.

Medium shot or midshot (MS) cuts the body just below or above the waist.

![]() Long shot (LS) or wide shot (WS) generally features the entire person in the frame, just above and below the body. The European term for a long shot of a person is a full shot (FS).

Long shot (LS) or wide shot (WS) generally features the entire person in the frame, just above and below the body. The European term for a long shot of a person is a full shot (FS).

![]() Extreme (or extra) long shot (ELS or XLS) or very long shot (VLS) shows significant space above and/or below the subject.

Extreme (or extra) long shot (ELS or XLS) or very long shot (VLS) shows significant space above and/or below the subject.

FIGURE 7.2

When shooting people, shots are classified by the amount of a person taken in.

Long shots have the advantage of allowing the viewers to select, to choose whatever attracts their attention in the wide view. But it also gives them the opportunity to look around and start thinking about whatever catches their interest rather than concentrating on the specific point that the program is trying to make at that moment.

Any well-edited program needs a series of closer and wide shots, each carefully chosen for its purpose. These shots assist the audience to establish the scene, observe what is going on, interpret action, and see details.

SHOOTING FOR THE INTERNET

Compressing video to be used on the Internet deteriorates the overall quality of the video. Any time footage is compressed, a bit of the quality has to be sacrificed. Here are a few points to keep in mind when shooting something that will be streamed on the Internet:

![]() Do not use more camera motion than you need. Whenever there is camera motion, the result is more compression.

Do not use more camera motion than you need. Whenever there is camera motion, the result is more compression.

![]() Use a tripod to give the most stable shot possible (you usually should use a tripod anyway).

Use a tripod to give the most stable shot possible (you usually should use a tripod anyway).

![]() Limit camera pans and tilts; when you do use them, make sure the motions are slow and smooth.

Limit camera pans and tilts; when you do use them, make sure the motions are slow and smooth.

![]() Light the subject well.

Light the subject well.

![]() Keep the background simple. The more detailed it is, the more the video will need to compress.

Keep the background simple. The more detailed it is, the more the video will need to compress.

7.4 HOW MUCH CAN WE SEE?

How much of the scene the camera shows will depend on several factors:

![]() The camera’s viewpoint (angle)

The camera’s viewpoint (angle)

![]() How far the camera is from the subject

How far the camera is from the subject

![]() The angle its lens covers

The angle its lens covers

As we noted earlier, the lens’s coverage (lens angle, angle of view) varies with its focal length. The zoom lens can be adjusted to any focal length within its range. If it is a 6:1 (six to one) system, then its widest angle will be six times the narrowest.

Some zoom lenses are fitted with a 2X extender (Figure 7.3). You can flip in this extender when you need a longer lens. The extender will double the focal length of the lens. However, there will be a noticeable light loss. Another way of altering the maximum or minimum angle of your lens system is to clip or screw on a supplementary lens (diopter lens). There are both telephoto and wide-angle conversion lenses available for this purpose. However, there can be some light loss, depending on the diopter (Figure 7.4).

FIGURE 7.3

The 2X extender is located on the side of the lens.

(Photo courtesy of Canon.)

FIGURE 7.4

Wide-angle lens adapter.

(Photo courtesy of VF Gadgets.)

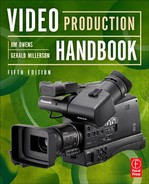

7.5 LENS ANGLES

Lens angles significantly impact the video images that the camera will capture, as well as the audience’s interpretation of those images.

If the angle from the viewer’s eyes to the sides of the TV screen is reasonably similar to that of the camera’s horizontal lens angle, the viewer will get a realistic impression of space, distance, and proportions. This is referred to as a “normal” lens angle. With today’s variety of screen sizes and shapes, this angle is by no means precise, but for all practical purposes we can assume that it is around 20 to 28 degrees.

What are the disadvantages if the camera operator shoots with a lens angle that is appreciably different from “normal”? Well, some interesting things can happen to the image. With some subjects, the audience may not even notice anything. However, wherever the audience can judge proportions and perspectives, such as looking up at a tall building or a close-up of a person, differences between images shot with different lens angles will be obvious.

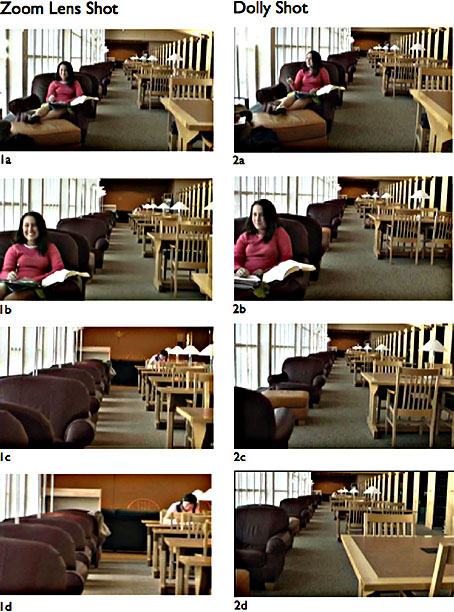

A telephoto or narrow-angle lens (long focal length) will give a magnified view of the scene, making it appear closer. The telephoto lens is advantageous when the camera operator cannot move the camera closer to the subject or does not want to. But there are also disadvantages. The telephoto lens often has the effect of flattening subjects because it compresses depth. This compression can also make subjects look unnaturally close (Figure 7.5). Movements are affected as well. Even fast-moving subjects seem strangely slowed by a telephoto lens as they move toward or away from the camera. The telephoto/narrow-angle lens is also difficult to hold steady; even the slightest vibration is magnified and causes image shake. The camera needs to be mounted or rested on something firm in order to obtain a steady image.

FIGURE 7.5

Changing the lens’s focal length alters its coverage proportion. In this situation, the camera stayed the exact same distance from the subject but the lens was changed.

(Camera photo courtesy of JVC.)

A wide-angle lens, on the other hand, shows us a much greater area of the scene. Everything in the image looks unusually distant. The lens seems to emphasize space and depth. Movements toward and away from the camera seem faster than they really are.

The wider the lens angle (i.e., the shorter the focal length), the easier it is to hold the camera steady and to move around smoothly while shooting. Although the wide-angle lens has many advantages, it cannot be used all of the time because there will be too many long shots. If the camera is moved in close to the subject in order to get a close-up shot, subjects will look distorted with a wide-angle lens.

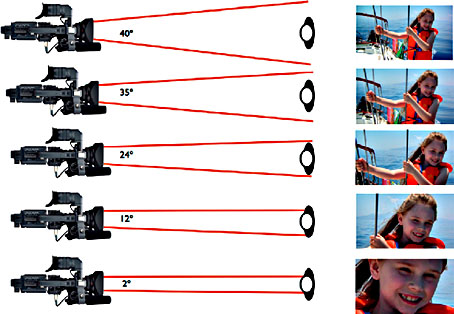

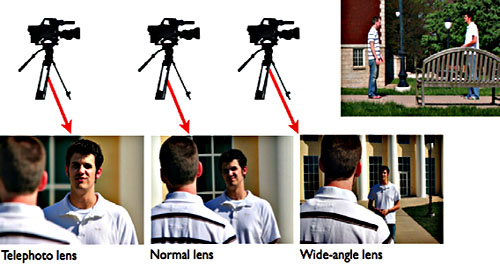

7.6 SO WHY MOVE AROUND?

If the subject can appear closer and farther away by simply varying the lens angle, why bother to move the camera? Why not just zoom the lens? It is far less trouble.

Although, at first glance, changing the focal length seems to give more or less similar results to those obtained when repositioning the camera, when you look at the image critically, it becomes obvious that there are distinct differences in the results (Figure 7.6). You’ll find these differences summarized in Tables 7.1 and 7.2.

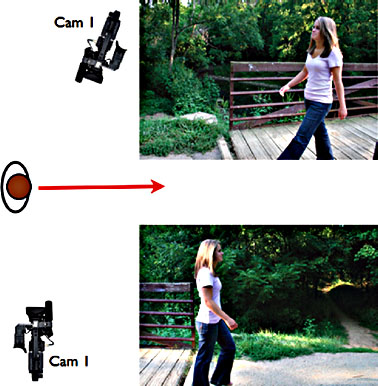

FIGURE 7.6

Changing the focal length (lens angle) of the lens significantly alters the proportions of the image. Subjects will be compressed or appear farther away. Note the impact that the telephoto and wide-angle lenses have on how the image looks.

(Photos by Josh Taber.)

Table 7.1 Selecting the Right Lens

| How much of the scene is sharp? |

|

| How prominent is the background in closer shots? |

|

| How hard is it to focus? |

|

| Camera shake |

|

| The impression of distance and depth in the picture | Because distant planes appear closer when shot with a narrow-angle lens, a distant back wall will look nearer and the room will appear smaller. Planes in the picture that are at an oblique angle to the camera (a side wall) will be shortened. Three-dimensional subjects will look squashed because their depth or thickness along the z-axis (near-to-far direction) is compressed. Conversely, a wide-angle lens will cause these same dimensions to appear stretched or deeper than usual. All planes will look abnormally far away. Impressions of size and space are exaggerated. |

| The accuracy of the shapes (geometry) | The wider the lens angle, the greater the distortion in closer shots of three-dimensional subjects. |

The lens’s focal length affects a number of areas simultaneously. How noticeable these effects are in the image depends on the subject and the scene.

The lens’s focal length affects a number of areas simultaneously. How noticeable these effects are in the image depends on the subject and the scene.

It’s a good general working principle to use a normal lens angle as much as possible and to move the camera viewpoint rather than just zooming in and out with a stationary camera. Actual camera movement gives life to an image. Whenever a camera moves, we see significant changes in the image. Various surfaces become progressively hidden as the camera moves past; others are gradually revealed. Although this effect becomes most obvious when travelling past foreground images, such as a series of columns or through a group of trees, it is one of those natural everyday phenomena that help us to interpret our three-dimensional world. It is even more pronounced when the camera trucks (or crabs) sideways.

Table 7.2 Why Change the Lens Angle?

| To adjust framing | A slight change in lens angle: When excluding or including certain objects and repositioning the camera or subject would ruin the proportions. |

| For otherwise unobtainable shots | Using a narrow-angle lens: To capture subjects that are situated a long distance from the camera and are inaccessible or where the camera cannot be moved (located on a camera platform). Using a wide-angle lens: Where the normal lens does not provide a wide enough shot because of space restrictions |

| To adjust effective perspective | Altering the lens angle and changing the distance between the camera and subject alters the subject/background proportions. Using a wider lens angle enhances spatial impression and increases the depth of field. Using a narrower lens angle reduces spatial impression and compresses the depth. |

| To provide simpler or more reliable changing operations | Zooming in/out instead of dollying may produce smoother, easier changes in shot size (but the perspective changes because of the focal lengths of the lens) (Figure 7.7). Zooming provides rapid changes in image size more safely than fast dollying (for dramatic effect or to suddenly reveal detail). Zooming in/out on a flat subject is indistinguishable from dollying, but it avoids focus-following problems. Lens angle changes can avoid close-up cameras coming into picture. |

Whenever a lens is zoomed, it simply magnifies and reduces the exact same shot. The natural effects that make shots from a moving camera so persuasive are simply not there.

There will certainly be times when the camera operator will deliberately widen or narrow the lens angle for practical or artistic reasons (Table 7.1). Don’t hesitate to vary the lens angle as needed to overcome a problem or to get an effect. Don’t just alter it casually. For example, if a camera operator is shooting a parade from a balcony and getting useful group shots with a normal lens angle, the operator may also use a wide-angle lens to take in the lengthy procession or a narrow-angle lens to show details. Using one lens angle would significantly limit the shot opportunities. The camera operator certainly couldn’t rely on running up and down to new viewpoints to provide the variety of shots needed.

If the director wants to show details on a distant statue located at the top of a building, he or she will certainly need to use a really narrow lens angle (long focal length). There will be some compromises to make. However, it’s unavoidable. Space will be squashed, and the form of the building itself may appear distorted. If you are using a narrow-angle lens when alternative camera positions are available, such distortions are unjustified.

On the positive side, the way in which a wide-angle lens exaggerates space offers invaluable opportunities in a crowded location or where the budget is limited. A wide-angle lens can make the smallest setting appear spacious. Even a couple of scenic flats linked together can create the illusion of an entire room if shot strategically with a wide-angle lens. Table 7.2 summarizes the practical advantages of the wide-angle lens.

7.7 THE ZOOMING PROCESS

There are several methods of controlling the lens’s zooming action. A camera operator working on a dramatic production may prefer a manual zoom system, which allows the shot’s coverage to be subtly readjusted as picture composition varies. But for the split-second decisions and fast zooms involved when shooting a sports event, motorized systems may prove more convenient.

Controlling the Zoom

There are three primary ways to control a zoom lens:

![]() Manual zoom control ring (or barrel ring). Turning a ring on the lens barrel varies the zoom lens’s focal length. This is a precise method, giving total control over the zoom action throughout the shot.

Manual zoom control ring (or barrel ring). Turning a ring on the lens barrel varies the zoom lens’s focal length. This is a precise method, giving total control over the zoom action throughout the shot.

![]() Power zoom. Many zoom lens systems can be controlled by a two-way rocker switch (see Figure 7.7), which activates a small motor. This will drive the zoom toward either the wide-angle or the telephoto end of its range, stopping where needed. The zoom speed may be adjustable or vary with finger pressure on the switch. The power zoom is widely used and particularly adaptable to all types of production in the studio and in the field. Zoom lenses on professional cameras generally have the switchable option of selecting between remote/manual/auto methods of iris control using the same hand.

Power zoom. Many zoom lens systems can be controlled by a two-way rocker switch (see Figure 7.7), which activates a small motor. This will drive the zoom toward either the wide-angle or the telephoto end of its range, stopping where needed. The zoom speed may be adjustable or vary with finger pressure on the switch. The power zoom is widely used and particularly adaptable to all types of production in the studio and in the field. Zoom lenses on professional cameras generally have the switchable option of selecting between remote/manual/auto methods of iris control using the same hand.

![]() Remote control. Remote control units are available for most cameras. They allow the camera operator to zoom the camera’s lens from behind the camera. This unit is generally mounted on a tripod arm (pan bar).

Remote control. Remote control units are available for most cameras. They allow the camera operator to zoom the camera’s lens from behind the camera. This unit is generally mounted on a tripod arm (pan bar).

The zoom lens can be a creative tool when used with discretion. When shooting a ballgame, zoom in to a closer shot as the action grows tenser. Zooming in rapidly so that the camera seems to swoop into a scene, particularly if it is on a jib arm arcing over the action, can produce dynamic results. But if you use a similar zooming action at the wrong time, your audience will probably get frustrated.

FIGURE 7.7

Zooming simply magnifies and reduces the picture. It does not produce the changes in the scene that arise as the dolly is moved through a scene. Increasing the focal length narrows the lens angle, filling the screen with a smaller and smaller section of the shot. These photographs illustrate the difference between the zoom and the dolly. Notice that there is not much of a difference between images 1b and 2b. However, as the dolly continues in 2c, it begins to show a different perspective, showing that there is a table between the two chairs on the left. Photo 1d zooms past the table, whereas the dolly perspective in 2d takes viewers up to the table and allows them to see the top of it.

To test this effect, try dollying in toward a person while zooming out at a corresponding speed and keeping the person the same size in the frame throughout. The result is bizarre, but it demonstrates the extent to which the lens angle and camera distance can affect a shot.

7.8 FOCUSING

Focus is an incredibly effective tool for directing the audience’s attention. The eye is always attracted to the part of the image that is in focus. This means that a knowledge of focus, depth of field, and lenses is essential if the camera operator and director want to use the camera creatively as a tool for storytelling.

There are a number of techniques that camera operators use to capture the action in focus.

![]() The most popular method is called follow focus. This technique requires the camera operator to continually change the focus as he or she follows the action, constantly turning the focus ring to keep the subject sharp whenever it begins to soften. However, focusing is not always as easy as that. With practice it can become a reflexive action. That does not mean it becomes easy.

The most popular method is called follow focus. This technique requires the camera operator to continually change the focus as he or she follows the action, constantly turning the focus ring to keep the subject sharp whenever it begins to soften. However, focusing is not always as easy as that. With practice it can become a reflexive action. That does not mean it becomes easy.

![]() Zone focusing refers to when camera operators are assigned a “zone” on the field of play or at a news event. They calculate the aperture so that basically everything will be in focus when the player or other subject moves into their zone. They generally do not try to shoot the subject when they are outside of their zone.

Zone focusing refers to when camera operators are assigned a “zone” on the field of play or at a news event. They calculate the aperture so that basically everything will be in focus when the player or other subject moves into their zone. They generally do not try to shoot the subject when they are outside of their zone.

![]() Prefocusing is when the camera operator focuses the camera on the subject before beginning to record. An example would be when a talk show host wants to show the audience a still photograph. Usually the host will place the photo on a stand located on his or her desk. Because one of the cameras has usually prefocused on the stand, the photo is instantly framed and in focus. Prefocusing is also required whenever a zoom lens is used. We will continue our discussion of prefocusing later in this chapter.

Prefocusing is when the camera operator focuses the camera on the subject before beginning to record. An example would be when a talk show host wants to show the audience a still photograph. Usually the host will place the photo on a stand located on his or her desk. Because one of the cameras has usually prefocused on the stand, the photo is instantly framed and in focus. Prefocusing is also required whenever a zoom lens is used. We will continue our discussion of prefocusing later in this chapter.

Many lenses also include macro systems, which are designed to provide a sharp image almost up to the actual lens surface. However, it is difficult to avoid a camera shadow when lighting such close subjects.

As the subject gets closer to the camera, the depth of field becomes shallower, so focusing is more critical. How noticeable a fall-off in sharpness is will depend on the amount of fine detail and tonal contrast in the subject.

7.9 AUTO-FOCUS

Many video cameras are fitted with an automatic focusing feature. This is a useful device for the occasions when the camera operator is preoccupied with following the action, is not sure where the subject is going to move to next, and might get the focusing wrong in the heat of the moment. But why not switch to auto-focus all the time so that we can forget about focusing altogether?

If the camera operator relies entirely on the automatic focus features in the camera, the resulting images will vary greatly. The auto-focus system simply sharpens the focus in a selected zone of the shot, irrespective of what is appearing there. So it needs to be used with care.

While auto-focusing can be very accurate, here are some situations that can be problematic:

![]() When the subject is not in the center of the picture. If two people are placed on either side of the frame, auto-focus may sharpen on an unimportant distant object in the center of the screen and leave the subjects soft-focused.

When the subject is not in the center of the picture. If two people are placed on either side of the frame, auto-focus may sharpen on an unimportant distant object in the center of the screen and leave the subjects soft-focused.

![]() The camera operator may want to focus on someone near the camera and a distant person at the same time, but auto-focus may sharpen on one or the other—or neither.

The camera operator may want to focus on someone near the camera and a distant person at the same time, but auto-focus may sharpen on one or the other—or neither.

![]() If shooting a subject through a foreground framework, such as a fence or branches, the system will focus on this foreground rather than the more distant subject (Figure 7.8).

If shooting a subject through a foreground framework, such as a fence or branches, the system will focus on this foreground rather than the more distant subject (Figure 7.8).

![]() If following someone who is moving around within a crowd, the auto-focus system is likely to readjust itself continually, focusing on nearby people instead of the intended subject.

If following someone who is moving around within a crowd, the auto-focus system is likely to readjust itself continually, focusing on nearby people instead of the intended subject.

![]() When the camera operator zooms to change the size of the shot, the autofocus system may refocus as the shot is recomposed.

When the camera operator zooms to change the size of the shot, the autofocus system may refocus as the shot is recomposed.

![]() If the camera operator is shooting a distant view and anyone (or anything) moves into the shot, closer to camera, the system may refocus on the secondary subject instead and defocus on the real subject. If, for example, the camera operator is panning around a scene and moves past a foreground tree, the system may readjust to focus on the tree.

If the camera operator is shooting a distant view and anyone (or anything) moves into the shot, closer to camera, the system may refocus on the secondary subject instead and defocus on the real subject. If, for example, the camera operator is panning around a scene and moves past a foreground tree, the system may readjust to focus on the tree.

When dealing with any of these situations, the best solution is to switch to manual focus to avoid the problems. Nevertheless, when used wisely, autofocus can be a useful tool.

7.10 DEPTH OF FIELD

Depth of field, or the focused zone, is usually defined as the distance between the nearest and farthest objects in focus. When shooting something in a distance, everything seems clearly focused. But refocus the lens onto something a few feet away, and only a limited amount of the shot will really appear sharply focused. Now focus on something very close to the camera, and sharpness becomes restricted to an even shallower zone.

FIGURE 7.8

Auto-focus systems cannot accurately focus on subjects behind broken-up foregrounds such as fences, branches, or the cage in the photo shown here.

(Photo by Lynn Owens.)

How obvious this effect is varies with the amount of detail in the scene.

The depth of field varies with the following factors:

![]() The distance at which the lens is focused

The distance at which the lens is focused

![]() The size of the image sensors

The size of the image sensors

![]() The focal length of the lens

The focal length of the lens

![]() The lens f-stop (aperture)

The lens f-stop (aperture)

Alter any of these elements, and the depth of field changes.

Depth is greatest when any of the following is true:

![]() The lens is focused at a distance

The lens is focused at a distance

![]() A wide-angle lens is being used

A wide-angle lens is being used

![]() The lens aperture is stopped down (f/16) (Figure 7.9)

The lens aperture is stopped down (f/16) (Figure 7.9)

FIGURE 7.9

You can achieve a large depth of field by using a wide-angle lens and a large-numbered f-stop such as f/22. The bright sunlight in this photo allowed the large-numbered aperture.

Depth of field is shallow in the following situations:

![]() When you are focusing on subjects close to the camera

When you are focusing on subjects close to the camera

![]() When you are using a telephoto (narrow angle) lens

When you are using a telephoto (narrow angle) lens

![]() When you open up the lens aperture (f/2) (Figure 7.10)

When you open up the lens aperture (f/2) (Figure 7.10)

Don’t be misled into thinking that you can use a wide-angle lens to improve depth of field in a shot every time. In some situations, the wide-angle lens works well at increasing the depth of field. However, when you switch to a wide-angle lens, the subject will look smaller, and by the time the camera gets close enough to compensate, the focused depth may become the same as before—only now there may be distortion and exaggerated depth too. It all comes down to the type of shot the director is trying to capture.

FIGURE 7.10

The shallow depth of field shown here was achieved with the use of a telephoto (narrow-angle) lens along with a fairly small-numbered f-stop such as f/4.

(Photo by Chad Crouch.)

7.11 MAXIMUM SHARPNESS?

Of course, it is not necessary to always get everything in the picture as sharp as possible. There are certainly situations when the director will want to see everything in the shot clearly—for example, when showing widespread action such as in a ballgame or when presenting an interesting building. Another example is when the director wants to create depth in the picture by having the shot include a person near the camera and another some distance away, both sharply focused. Then the camera operator could use a wide-angle lens, stopped down as far as the light levels permit.

There will be other times, though, when the director wants the audience to concentrate on a specific subject and disregard the surroundings. This can be achieved by deliberately restricting the depth of field or by using a larger lens aperture or a narrower lens angle. Now, because of the limited depth of field, the subject will appear sharp against a defocused background, where anything likely to confuse or distract merges into an indistinct blur.

7.12 DIFFICULT TO FOCUS?

Sometimes there is insufficient depth of field to focus clearly on the whole subject. That is a specific problem in close-up shots. Stopping the lens down would help, of course, but there may not be enough light to do so without underexposing the image. If it is impossible to increase the light level, what can one do? Several compromise solutions are available. However, please note the word “compromise“—the results may not always be optimum (Figure 7.11).

![]() The best method may be to sharpen focus on the most important part of the subject and leave the rest defocused. Although this situation is not ideal, it is a way to show the viewers exactly what you want them to see.

The best method may be to sharpen focus on the most important part of the subject and leave the rest defocused. Although this situation is not ideal, it is a way to show the viewers exactly what you want them to see.

![]() It is possible to split focus and choose a compromise focusing distance that keeps all subjects clearly enough in focus.

It is possible to split focus and choose a compromise focusing distance that keeps all subjects clearly enough in focus.

![]() Sometimes a pull focus or throw focus is appropriate. For example, suppose that two people are being shot at different distances from the camera and it is not possible to get them both in sharp focus. The camera operator might start by focusing on the first person, and then, at the appropriate moment, change the focus to sharpen on the second person. The method successfully directs the audience’s attention, and the effect can be dramatic. So it is a technique that needs to be reserved for the right occasion.

Sometimes a pull focus or throw focus is appropriate. For example, suppose that two people are being shot at different distances from the camera and it is not possible to get them both in sharp focus. The camera operator might start by focusing on the first person, and then, at the appropriate moment, change the focus to sharpen on the second person. The method successfully directs the audience’s attention, and the effect can be dramatic. So it is a technique that needs to be reserved for the right occasion.

![]() Ideally the situation can be improved by moving the subjects or altering the camera position so that they are both about the same distance from the camera and within the available depth of field.

Ideally the situation can be improved by moving the subjects or altering the camera position so that they are both about the same distance from the camera and within the available depth of field.

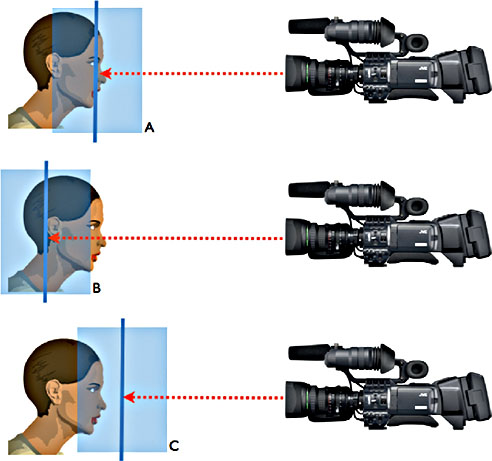

FIGURE 7.11

When accurately focused, (A), the most important part of the subject should be the sharpest. The specific focus point (as represented by the darker blue line in the illustrations) should have a large enough depth of field (represented by the light blue field) to keep the subject in focus as she moves a little forward or backward. Note that the incorrect focus point, as demonstrated in B and C, would make it easier for the subject to move out of focus.

(Camera photo courtesy of JVC.)

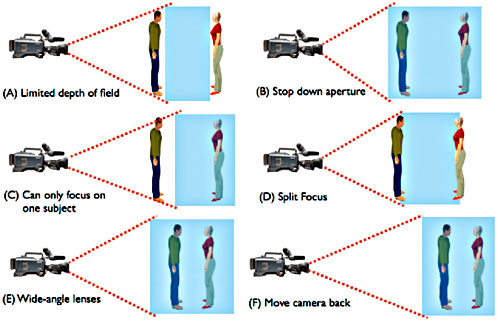

Limited Depth of Field

If the depth of field is too limited for your purposes, you can do the following (Figures 7.12 and 7.13):

![]() Stop down. Increasing the depth of field will require a high light level.

Stop down. Increasing the depth of field will require a high light level.

![]() Focus on one subject. Let others soften.

Focus on one subject. Let others soften.

![]() Split focus. Spread the available depth between both subjects (now none is really sharp).

Split focus. Spread the available depth between both subjects (now none is really sharp).

![]() Move subjects closer together. This way, they will be roughly the same distance from the camera.

Move subjects closer together. This way, they will be roughly the same distance from the camera.

![]() Use a wide-angle lens. The depth of field will increase, but the subject will now appear smaller.

Use a wide-angle lens. The depth of field will increase, but the subject will now appear smaller.

FIGURE 7.12

Pulling focus can be used to guide the viewer through a scene. Notice the change of focus in the two photos shown here.

(Photos by Josh Taber.)

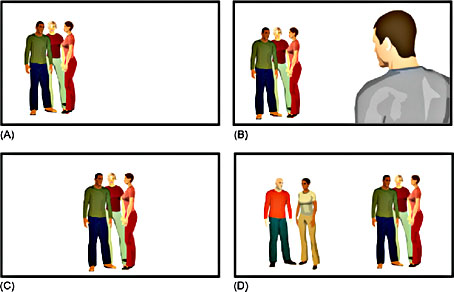

FIGURE 7.13 Dealing with a limited depth of field. When a limited depth of field creates problems (A), here are a few solutions:

![]() If the aperture is stopped down (a higher f-stop number), the depth of field will increase (B).

If the aperture is stopped down (a higher f-stop number), the depth of field will increase (B).

![]() If there is not enough depth to cover two people (C), it may be possible to split focus (D).

If there is not enough depth to cover two people (C), it may be possible to split focus (D).

![]() Wide-angle lenses have a much wider depth of field than a telephoto lens (E).

Wide-angle lenses have a much wider depth of field than a telephoto lens (E).

![]() The closer the camera is to the subject, the shallower the depth of field. By moving the camera farther back, a wider depth of field will be created. However, the subject will be smaller.

The closer the camera is to the subject, the shallower the depth of field. By moving the camera farther back, a wider depth of field will be created. However, the subject will be smaller.

(Camera photo courtesy of Panasonic.)

7.13 PREFOCUSING THE ZOOM LENS

The zoom lens is a fine tool for the creative camera operator, but it also has some nasty pitfalls for the unwary. When following fast-moving action, the camera operator may run into difficulties.

Depth of field will significantly change as a zoom lens moves through its focal length range. When zoomed out (wide-angle view), there is normally considerable depth of field available, and focusing is easy. Usually, so much looks sharp in the picture that the camera operator cannot judge exactly where the best focus is. But zoom in to a close-up shot (telephoto or narrow-angle view), and the depth of field becomes relatively shallow. In fact, there is always the danger that instead of being focused exactly on the subject, the lens was really focused some distance nearer or farther away. Consequently, when zooming in from a good, sharp long shot to a close-up, the image may be completely defocused, and then the camera operator has to hurry to correct the focus. This is especially tense for live, on-air productions (Figure 7.14).

FIGURE 7.14

When focusing is extremely critical, especially in dramatic productions, a focus puller is often used to adjust the focus of the camera. This allows the camera operator to concentrate on framing.

The only solution to this dilemma is to remember to prefocus the zoom before taking the shot. The camera operator takes a trial close-up shot of the subject immediately beforehand so that the focus can be crisply adjusted; then he or she zooms back to the wide shot (without changing distance), ready to start shooting the action.

PREFOCUSING THE ZOOM

If zoom lenses have not been prefocused on the subject by zooming in for the close-up, the picture may become defocused during the zoom move from long shot to close-up.

![]() The long shot may look perfectly in focus. However, this is because of the depth of field created by the wide-angle lens.

The long shot may look perfectly in focus. However, this is because of the depth of field created by the wide-angle lens.

![]() As the lens zooms in to a telephoto (narrower angle), the depth of field becomes much more restricted, and it is possible that the shot will be totally out of focus.

As the lens zooms in to a telephoto (narrower angle), the depth of field becomes much more restricted, and it is possible that the shot will be totally out of focus.

![]() The best method of keeping zoom shots in focus is to zoom in close to the subject, focus, and then zoom out. This should allow the camera operator to zoom in and out, keeping everything in focus.

The best method of keeping zoom shots in focus is to zoom in close to the subject, focus, and then zoom out. This should allow the camera operator to zoom in and out, keeping everything in focus.

EXPOSURE

7.14 What Is “Exposure”?

Every video camera requires a certain amount of light to function effectively and produce quality images. However, the camera’s sensors can only handle a limited range of tones. When shots contain a wide range of tones (brightness values), directors cannot hope to reproduce them all absolutely accurately in the final image.

![]() If the amount of light from a surface exceeds the chip’s upper limit, it will reproduce as white in the video picture. It will burn out or clip to a blank white.

If the amount of light from a surface exceeds the chip’s upper limit, it will reproduce as white in the video picture. It will burn out or clip to a blank white.

![]() Conversely, where a surface reflects too little light, it will fall beyond the system’s lower limit and crush to an overall black tone.

Conversely, where a surface reflects too little light, it will fall beyond the system’s lower limit and crush to an overall black tone.

The average brightness of the lens image falling onto the sensor is primarily determined by the lens aperture (f-stop). The goal is to adjust the aperture so that the most important tones, usually people’s faces, are clearly visible. This process is called “adjusting the exposure.” “Correct exposure” is a subjective choice.

The video camera operator can always see the image in the viewfinder or on the screen. The operator can assess the picture continually, and if it is over- or underexposed, he or she can immediately compensate. In video/television production, the camera itself is the light meter.

Let’s take a practical example. The camera operator shoots someone who is standing out in the sunlight. He or she adjusts the exposure by altering the lens aperture until the person looks good in the viewfinder or, better still, on a high-grade picture monitor. The subject’s face tones, in particular, appear quite natural—neither too light nor too dark. However, the subject’s white shirt looks washed out and has no detail, or maybe the subject’s pants look black, with no signs of modeling in the material at all. The director might be willing to accept these results, unless this is a fashion shoot, meant to show off the quality and attractiveness of the clothing.

Don’t expect to always show good tonal gradation in everything in the scene. There will usually be something in the shot that crushes out to white or black. How successfully the shot is exposed will depend not only on the range of the tones appearing in it but also on the effect the director wants to capture. The director may want to deliberately underexpose an image to make it look more shadowy and mysterious. Or he or she might overexpose a shot of the seashore to create a high-key effect (Figure 7.15).

It is easier to control the tones in a studio by altering the lighting or by adjusting the aperture. But elsewhere, particularly on location, the camera operator may have to make the most of what is available, and at times the selected lens aperture may have to be something of a compromise.

If parts of the location scene appear as large blank white or black areas in the image, there may not be much you can do about it. The obvious remedy is to reframe the shot or change the camera position to keep the harsh white or black areas out of the picture altogether. If lighting equipment is available, it may be possible to lighten darker tones or shadowy areas (Figures 7.16 and 7.17). Occasionally, troublesome surfaces can be masked off (have someone standing in the foreground to obscure a large blank white wall). If the object that catches the eye is small, such as the sun reflected in a table mirror, it may be possible to reangle it or remove the mirror altogether. Again, choosing the optimum exposure may involve a certain amount of compromise.

FIGURE 7.15

Directors cannot expect that every image will be captured with good tonal qualities. In this image, the director could choose to get good exposure of either the field of play or the audience.

(Photo by Shannon Mizell.)

FIGURE 7.16

Lights were used to try to match the exposure of the presenter to the details on the ice of the hockey rink behind the talent. Otherwise, the ice would be entirely white or the talent would be entirely black.

FIGURE 7.17

Additional lighting or some type of reflector can be used to lighten darker areas when working outdoors.

7.15 UNDEREXPOSURE AND OVEREXPOSURE

When a picture is underexposed, all of its tones will appear much darker. Results are usually dull and lifeless. Detail and modeling may be clear in light tones (even clearer than usual), but middle to dark areas look muddy and merge to black (Figure 7.18).

FIGURE 7.18

Taking the time to expose an image properly is essential for quality pictures.

It is worth remembering too that when the camera receives insufficient light from the scene, other image defects can also develop, such as lag (image smearing on movement) and picture noise.

To fix underexposure, open the lens aperture to provide the camera’s chips with a brighter lens image. (Of course, this will reduce the depth of field to some extent and could make focusing harder, particularly when using a narrow-angle lens.)

Increasing the video gain on a camera does not really compensate when the camera sensor is not getting enough light for maximum performance; it simply boosts the video signal. However, it will certainly enhance the picture, perhaps even making it look bright and well contrasted. The downside to video gain is that the quality of the image deteriorates the higher the gain is set.

When a picture is overexposed, all of its tones will appear unusually light. Even fairly light tones in the scene will block off, whereas darker areas of the scene will often be easier to discern than normal. Stopping down a little improves reproduction in light tones but reduces the visibility of shadows. However, it is impossible to electronically compensate for grossly over- or underexposed areas. They will have little detail. Again, lowering the video gain setting is not a good solution. It will simply reduce the overall brightness of the image (Figure 7.18).

7.16 AUTOMATIC EXPOSURE

If judging exposure is a matter of artistic choice, how is it that so many video cameras utilize an automatic iris most of the time? Leaving aside those people who would otherwise be careless about exposure, the auto-iris is a useful tool when you are in a difficult spot. It continually adjusts the lens aperture to maintain an average video signal.

Under typical location conditions, whether outside or inside, light levels can change considerably as the camera’s viewpoint changes. If you were to walk around a location with a light meter, you would probably see its needle bouncing up and down each time you repositioned. The camera may need to be stopped down to f/16 in a sunlit courtyard but opened up to f/2 inside a house.

Strictly speaking, if the camera needs to follow along with action that moves from the exterior to the interior, then the camera operator needs to keep an eye on the viewfinder and adjust the exposure to match the different light levels.

Some may wonder, if camera operators already have to follow focus as they move and keep the shot properly framed, how can they adjust the exposure at the same time? That is why even experienced camera operators under these conditions may leave exposure to the auto-iris and concentrate on focusing and composing the picture.

Ideally, the lens aperture is set for the correct exposure of the main subject. If the same subject appears in a succession of shots in the same scene, the exposure needs to be constant, not change about as incidental background tones vary. Yet changes of this kind are unavoidable when using an auto-iris.

It is easy to fool an auto-iris. If a lighter tone is brought into the shot (e.g., the subject opens a newspaper or takes off a jacket to reveal a white shirt), the iris will close down a little and darken all the other tones in the picture, including the subject’s face. Take the light area out of the shot or pan away from it, and the auto-iris will open up. Image tones will lighten. Take a long shot, and face tones may look dark, but zoom in to a close shot, and because other picture tones are now excluded, the face reproduces much lighter.

Under certain conditions, the auto-iris can also cause bad underexposure. Normally, if you are shooting inside a room, the system will open up and produce well-exposed images. However, suppose the person being filmed moves over to a window. The auto-iris will see the intense daylight and stop the lens down. As a result, the person could now appear as a silhouette, while the sky may be well exposed (Figure 7.19).

FIGURE 7.19

Brightly lit backgrounds will cause the auto-iris to underexpose the main subject.

Some cameras have a backlight control that can be switched on when the background is bright in the image. This opens up the iris an arbitrary stop or so above the auto-iris setting to improve the subject’s exposure. This may overexpose the lightest areas, but the subject would now be better exposed.

Although the auto-iris system has its own problems, these variations are often preferable to badly overexposed or underexposed images. And in practice, they may be too slight to worry about or may even pass unnoticed by the viewer. However, they are still there. Your decision about how to respond to these challenges all depends on how critical the final result is.

7.17 CAMERA ADJUSTMENTS

Manufacturers create a default that will give the camera operator the best average setting. Generally these settings produce a good image. However, there are times when a few adjustments can lead to great images. Our impressions of picture quality are very subjective. It is surprising how often we prefer a picture that looks just a little warmer or has slightly exaggerated contrast when compared with the original scene.

The most common camera adjustments relate to the lens, focus, lens aperture, shutter, video gain, and white balance. These changes can usually be completed on the camera or with a camera control unit (Figure 7.20). Within certain limitations, almost all of these areas also can be adjusted with editing software. Image quality can be altered in a number of ways, for a specific shot or perhaps for an entire scene:

FIGURE 7.20

Instead of using a white card to white-balance the camera, one can use light blue cards for the color balance process, resulting in a warmer image.

(Photos courtesy of Vortex.)

![]() Sharpness. Sharpness can be adjusted (or manipulated) by the use of special-effect filters (mist, soft focus, ripple, etc.) and by defocusing the lens.

Sharpness. Sharpness can be adjusted (or manipulated) by the use of special-effect filters (mist, soft focus, ripple, etc.) and by defocusing the lens.

![]() Brightness. Brightness can be adjusted with the lens aperture or video gain.

Brightness. Brightness can be adjusted with the lens aperture or video gain.

![]() Tonal range and contrast. Tone and contrast can be modified by adjusting the gamma (higher gamma settings produce a coarser, exaggerated contrast lower settings result in thin and reduced tonal contrasts). Lowering the pic-ture’s black level moves all picture tones toward black and crushes the lowest tones. Raising the black level lightens all picture tones but does not reveal detail in blackest tones.

Tonal range and contrast. Tone and contrast can be modified by adjusting the gamma (higher gamma settings produce a coarser, exaggerated contrast lower settings result in thin and reduced tonal contrasts). Lowering the pic-ture’s black level moves all picture tones toward black and crushes the lowest tones. Raising the black level lightens all picture tones but does not reveal detail in blackest tones.

![]() Color intensity. Increased saturation emphasizes the strength of color Reduced saturation (diluting with white) gives a more pastel effect.

Color intensity. Increased saturation emphasizes the strength of color Reduced saturation (diluting with white) gives a more pastel effect.

![]() Color fidelity. To simulate firelight or moonlight or make a picture warmei or cooler, shooting with “wrong” color temperature filters or gels may suffice Otherwise, color balance can be changed by adjusting the video gain, white balance, black level, or gamma of the separate red, green, or blue color channels (Figure 7.21).

Color fidelity. To simulate firelight or moonlight or make a picture warmei or cooler, shooting with “wrong” color temperature filters or gels may suffice Otherwise, color balance can be changed by adjusting the video gain, white balance, black level, or gamma of the separate red, green, or blue color channels (Figure 7.21).

Changing Camera Settings

Changes in black level or gamma should only be made if a waveform monitor is available. I would never suggest altering individual RGB settings in camera. These changes should be left until post. Furthermore, whatever settings you choose to alter, I would recommend that you always carefully mark the original settings of the controls so that they can be returned to their original positions/settings, thus restoring the camera to its former status (Figure 7.22).

—Tony Grant, Producer/Director

FIGURE 7.21

Camera remote control unit (CCU). The CCU can be used from a remote location to control the main electronic adjustments in the camera that affect picture quality (exposure, black level, gain, etc.).

(Photo courtesy of JVC.)

FIGURE 7.22

Waveform monitors are used when adjusting camera settings.

(Photo courtesy of Tektronix.)

7.18 PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS

When shooting a scene that contains a variety of tones, it may not be possible to accommodate the entire range. There are times when the director may have to accept that the lightest or the darkest areas will be lost in detail-less highlights or shadows. However, a few other options can be utilized to enhance the image in some limited situations.

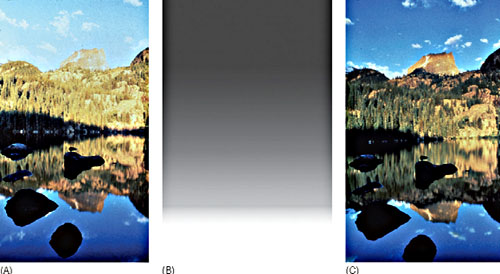

Graduated Filters

When shooting in the field, there are times when you will find that the main subject is properly exposed, but distant skies are far too bright and distracting. This can be a particular problem when the foreground subjects are dark toned.

A graduated filter can often help you to overcome this dilemma. Its upper section has a neutral gray tint, which reduces the brightness of the image in that part of the picture. So it will “hold back” the overbright skies while leaving anything in the clear lower section unaffected.

Graduated filters have a gradual tonal transition, giving a soft blend between the treated and untreated areas. There are also graduated filters that can be used to create a deliberate effect (Figure 7.23). One-half of the filter may be orange and the other half clear or blue tinted. Some color filters have a central horizontal orange or yellow band, which, with care, may simulate the effect of a sunset.

FIGURE 7.23

(A) A graduated filter. (B) A scene shown without the use of a filter. (C) Here the camera operator used a graduated filter to enhance the sky.

(Photos courtesy of Tiffen.)

The main disadvantages of this otherwise useful device are the following:

![]() The filter will not work for every shot; it only works in specific situations.

The filter will not work for every shot; it only works in specific situations.

![]() You cannot pan or tilt the camera when using this filter, or the effect will be obvious to the viewer.

You cannot pan or tilt the camera when using this filter, or the effect will be obvious to the viewer.

Tonal Adjustments

How successfully can a camera reproduce the scene that is being shot? The tones that are seen on the screen are usually expected to correspond exactly to those in the scene. However, in practice, video has a tendency to exaggerate or to reduce apparent tonal contrasts in the reproduced picture. At the lightest and darkest extremes, video cannot distinguish between subtle differences in brightness, so those tones appear merged into dense shadow or blank highlights.

As we saw earlier, if there is a difficulty in seeing detail or tonal differences in shadows, trying to improve things by opening up the lens aperture will probably overexpose the lightest tones. Extra video amplification won’t help either. Some cameras include a black stretch control, which will make shadow detail clearer and improve tonal gradation in darker tones. There may even be corresponding camera circuitry to improve reproduction of the lightest tones.

TEN COMMANDMENTS OF SHOOTING VIDEO

1. White balance must be done. Don’t forget to white balance your camera in every lighting situation.

2. Take plenty of recording material. Take two to three times as much recording medium (flash memory, hard drives, or tape) than you think you will need. It is better to have too much than not enough.

3. Take more batteries than you think you can possibly use. Also, take your power adapter and charger with you even if you think you won’t be near power … you never know.

4. Use manual focus. Since auto-focus always searches around as you move your camera or your subject moves, you have more control when you manually focus the camera. Plus, it also saves your battery for other things.

5. Don’t zoom when shooting. (Okay, you can do it sometimes.). However, zooming during the shooting of a production is often the sign of an amateur. Don’t overuse it.

6. Get a mic. Use an external microphone to capture your audio. The in-camera microphone picks up distracting camera sounds. Also, always monitor your audio with a headphone. Not listening to your sound is like not looking at your viewfinder.

7. Use a tripod. There is nothing like a steady shot. Most professionals use tripods 90% of the time.

8. Don’t use a tripod. Okay, I know that this sounds like I just contradicted #7… oh well. Video is made to capture motion—either your subject’s motion or your camera’s motion. There is nothing like a dynamic shot, such as following someone through a crowd. This movement may require more takes and is difficult to master. When successful, it really adds energy to a production.

9. Make sure that you shoot plenty of footage. You don’t want to have to go back to shoot additional cover footage. Shoot plenty of cutaways and extra material. Today’s recording medium is cheap.

10. Take care of your gear. You need it to work. Keep it in protective cases, keep it from dust, and keep the lenses clean.

HANDLING THE CAMERA

7.19 Panning and Tilting

If it is not possible to get a sufficiently wide shot of the subject to show it completely, or if the distant view does not have enough detail, there are two general solutions.

The first possibility is that a series of separate shots can be taken, which are then edited to build an overall image in the minds of your audience. However, when developing this sequence, avoid amassing a disjointed, random collection of images.

Alternatively, the camera can be panned or tilted carefully and systematically over the scene to relate various parts (Figures 7.24 and 7.25). Take care, though, to avoid a series of brief, erratic pans or long, “empty” pans that wander over unimportant things. Each pan needs to have a clear purpose and finish by settling on an interesting feature of the scene. Above all, avoid panning from side to side over the scene. Although this can be a great temptation, you are not likely to use these sequences when you see the results.

FIGURE 7.24

A pan shot is when the camera pivots left or right on a camera mount, such as a tripod, or as a handheld camera.In a pan shot, the camera mount or handheld operator pivots the camera.

(Photo courtesy of Vortex Media.)

FIGURE 7.25

A tilt shot pivots the camera up or down on a camera mount. The correct command is “tilt up” or “tilt down.”

Like all camerawork, panning and tilting should be smooth and controlled. Above all, avoid overshooting, such as going beyond the final point and then having to correct the shot by reversing the pan a little. It draws attention to the error. Ideally, each movement should be brought to a smooth finish. If the pan has a jerky start or finish, is hesitant, its speed is uneven, or it wavers up and down, the result will look crude in the finished production.

Don’t be tempted to pan or tilt too quickly because the image may become an indecipherable blur. Most of us fall into that trap when first shooting a landscape. We pan briskly, trying to show everything only to find that the result on the screen is extremely disappointing as details break up (“strobe”) during the movement.

Try panning or tilting across a scene so that it takes an object roughly 5 seconds to travel from one edge of the screen to the other. That is about the fastest rate that can be used to avoid movement breakup. There are situations in which a rapid whip pan or zip pan can be used deliberately for a startling dramatic effect, but the technique is seldom used.

If a handheld camera is required to follow the action over a wide arc, camera operators should not try to turn their bodies on their heels. Instead, the body should be facing midway through the action, ready to make a smooth, balanced movement, and the camera operator will twist his or her body to follow the action. The result will be much more controlled. Keeping the knees slightly bent can also help (Figure 7.26). When using a tripod, remember to check that it is level before panning, or the framing may move upward or downward during the pan.

FIGURE 7.26

When following the subject in a wide arc, the camera operator’s feet should face the midpoint of the arc. This will allow the camera operator to pan smoothly with the action.

7.20 FOLLOWING MOVING SUBJECTS

There is a lot more to taking shots of a moving subject than simply keeping up with it. Dealing effectively with a moving camera is the difference between a good camera operator and a great camera operator.

When one is handholding a camera still, anything moving around in the shot can quickly reach the edge of the frame and move out of sight, particularly if it is moving quickly in a “tight” shot that is filling most of the screen. There are several ways to deal with this situation:

![]() The moving subject can be allowed to move out of the frame altogether (“exit”). This is a good idea if the director wants the audience’s attention to move on to a new subject.

The moving subject can be allowed to move out of the frame altogether (“exit”). This is a good idea if the director wants the audience’s attention to move on to a new subject.

![]() The camera operator can widen the shot by zooming out or moving back to include the movement. This is often the best solution if someone is pacing back and forth or waving his or her arms around (Figure 7.27).

The camera operator can widen the shot by zooming out or moving back to include the movement. This is often the best solution if someone is pacing back and forth or waving his or her arms around (Figure 7.27).

![]() The operator can pan or tilt the camera to keep the subject in the shot (for example, to follow somebody as the person moves around a room). However, don’t use too close a shot here. Not only will the subject itself look cramped in the frame, but it will also be difficult to follow the action smoothly.

The operator can pan or tilt the camera to keep the subject in the shot (for example, to follow somebody as the person moves around a room). However, don’t use too close a shot here. Not only will the subject itself look cramped in the frame, but it will also be difficult to follow the action smoothly.

![]() The camera position can be moved, such as an arc, so that the subject remains in shot.

The camera position can be moved, such as an arc, so that the subject remains in shot.

![]() The camera can move along with the subject, such as a tracking shot, keeping the subject in the frame throughout the action.

The camera can move along with the subject, such as a tracking shot, keeping the subject in the frame throughout the action.

![]() Instead of following the movement, you can let it leave the frame and then pick up the action from a new viewpoint.

Instead of following the movement, you can let it leave the frame and then pick up the action from a new viewpoint.

FIGURE 7.27

It can be difficult to shoot close-ups during fast-moving action. Generally the camera operator needs to zoom out a little to effectively cover the action.

If a single camera is being used to cover the action, the camera operator would need to stop recording, move to the next position, set up the new shot, and begin recording again. In the meantime, some of the action has been missed—unless, of course, the action can be repeated. In that situation, the action begins again from just before the camera was moved to the second position. If two or more cameras are being used, none of the action has to be missed; just cut to the second camera at the right moment.

All of these methods work. The camera operator or director must consider which one is most appropriate, both artistically and practically.

7.21 FRAMING MOVEMENT

At first sight, it seems logical to keep a moving subject exactly in the middle of the picture. However, the image will look unbalanced and boring. Instead, when panning with a moving subject that is running toward something, position the subject a little behind the center of the frame. If the subject is running away from something (such as a thief in a police chase scene), keep the subject just over the center frame (Figure 7.28). The image will look more dynamic; the faster the movement, the greater the offset. Most important, don’t let the subject “move around the frame” through uneven planning.

FIGURE 7.28

When shooting a fast-moving subject, keep the subject behind the center of the frame. The image will be more dynamic.

(Photo by Mark Stokl.)

7.22 WALKING

Handheld shooting is difficult. Unless the director is looking for a bouncy camera style, handholding a camera takes a lot of practice. It is not as easy as it seems to keep the camera level steady and well-composed shots in sharp focus.

When the subject moves away, the obvious response is to have the camera operator walk with the person. However, this can be a significant problem. The route has to be checked in advance to ensure that there are no carpets, steps, cables, people, or posts in the pathway. The camera operator could easily meet unseen hazards as he or she concentrates on the viewfinder image. That is why experienced camera operators develop habits of glancing around (to check out their surroundings and nearby action) and keeping both eyes open when using an eyepiece viewfinder. The safest and best strategy is to use a camera assistant who can get people out of the camera operator’s way or guide the operator around problematic obstacles (Figure 7.29).

FIGURE 7.29

Camera assistants are invaluable to a handheld or Steadicam operator. The assistants can guide the operator around obstacles.

There is always a certain amount of bounce in the camera’s shot as the camera operator walks, especially if he or she is moving quickly. This unevenness may be unimportant or even dramatic if the camera is following someone’s moves over uneven ground, through a crowd, or through a forest. But it can be distracting when the operator is walking within a building.

If moving shots, particularly over rough terrain, are required, the most practical way to avoid camera bounce is to attach the camera to a stabilizer unit such as the Steadicam. This camera mount compensates for irregular movements. There are also several forms of optical or electronic image stabilization, which diminish vibrations and smooth out variations.

7.23 SHOOTING FROM VEHICLES

Whenever shooting from any vehicle, there are a number of points worth bearing in mind:

![]() Resist the temptation to rest the lens or the camera on the glass or the vehicle’s body, since vibration can damage the equipment and blur the images.

Resist the temptation to rest the lens or the camera on the glass or the vehicle’s body, since vibration can damage the equipment and blur the images.

![]() Smeary, rain-speckled, dusty, or tinted windows can significantly degrade picture quality, especially if sunlight is falling on them. The images will show a flattened contrast, defocused blurs, and changing color values that become particularly obvious when edited with other shots.

Smeary, rain-speckled, dusty, or tinted windows can significantly degrade picture quality, especially if sunlight is falling on them. The images will show a flattened contrast, defocused blurs, and changing color values that become particularly obvious when edited with other shots.

The position of the camera in the vehicle will influence the audience impact of the images. Facing forward, subjects appear to move toward the camera, getting closer and increasingly clearer. This is a powerful viewpoint that provides continual interest. A rear view, however, shows everything moving away from the camera, and the audience’s interest tends to fall. No sooner does something come into shot than it quickly becomes too small to see properly. Side windows are useful for shooting distant subjects, but anything close rapidly moves across the screen out of focus.

Shooting someone inside a moving car requires a certain amount of agility. A wide-angle (short-focus) lens is essential because it enables the camera operator to get sufficiently wide shots of the driver. Typical camera positions include the following: seated beside the driver, crouched in the passenger’s foot space, or leaning over from a rear seat. Cameras can also be mounted outside the car, using beanbags, bolt-on brackets, or suction-held pads (Figure 7.30).

FIGURE 7.30

Many devices can be used to secure a camera to a moving car. This photo illustrates how a Cine Saddle (a sophisticated beanbag) can be tied onto a car for forward (toward the road) or backward (toward the driver) shots (also see Figure 8.15).

THE BASICS OF SHOOTING

7.24 Practical Conditions

There are no absolute “rules” for shooting effective images. In fact, if the images are arranged too systematically, the results can look boring and artificial. But there are a number of situations that need to be avoided.

During a busy shooting schedule, there generally is not time to experiment with the composition of each shot. Many times, quick decisions have to be made because a live event is unfolding, there may be production or broadcast deadlines, the crew is standing by, and, from a practical standpoint, time is money. So the pressure is generally on to make quick decisions. However, if the camera operator and director understand composition basics, they will know what to look out for and realize how to adjust the shot for the most appropriate effect. Once camera operators recognize the characteristics that make images unsuccessful, and many are a matter of common sense, they will avoid them instinctively.

Unlike a painter, who can arrange objects on the canvas to suit his or her ideas, a video camera operator usually has to make the most of what is already there. But that does not mean that what the viewer sees cannot be controlled. The director and camera operator can do a great deal to change an image’s appeal. They can select the viewpoint carefully, choose the appropriate lens angle, or control the way the shot is framed. Sometimes they can reposition the subject or some of the objects to further improve the image.

SHOOTING IN 3D

Audiences tend to want to explore a 3D frame longer than they would a 2D frame. Since there is more information to be imparted, most shots tend to stay on the screen a bit longer.

—Steve Schklaire, CEO, 3ality Digital Systems

When shooting in 3D everything is multidimensional. That means all the objects seen on the screen are typically in constant focus as they are with human vision. This is one of the reasons a rack focus effect in 3D looks uncomfortable to the eye and should be avoided.

—David Kenneth, President, I.E. Effects

7.25 SELECTING THE RIGHT SHOTS