THE ORIGINS OF THE COCKTAIL

WHEN IT COMES TO COCKTAILS, IT’S BEEN A WILD RIDE.

Of course, you can drink cocktails like perfect ladies and gentlemen if you have a mind to (though the more you consume, the harder that will be), but the ride the cocktail itself has taken—whew!

I’ll give it to you in a blow-by-blow narrative, but first a little quiz. How long do you think the cocktail has been around? Since before Prohibition? Pre–World War I?

Try again. The venerable and very American cocktail is more than 200 years old. Hell, the Martini is over 150. That’s a lot of history there, embedded beneath our cultural skin, for something as apparently frivolous as a simple mixed drink, but read on.

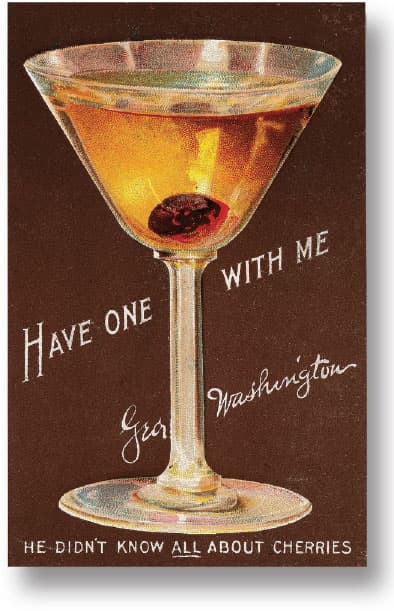

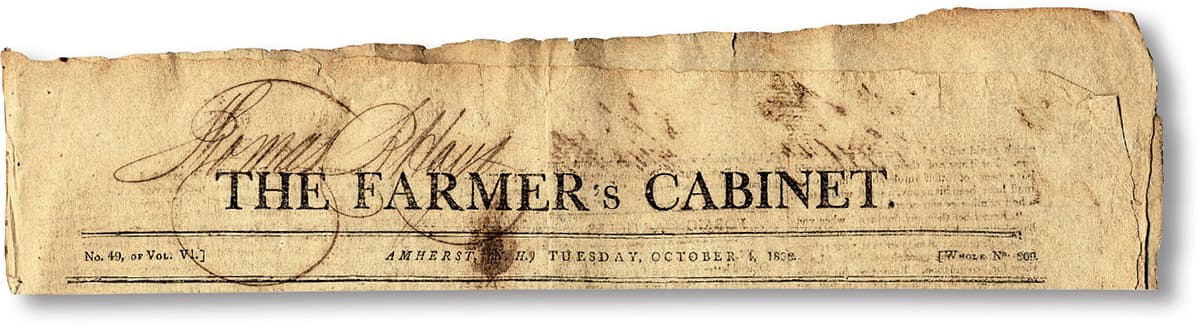

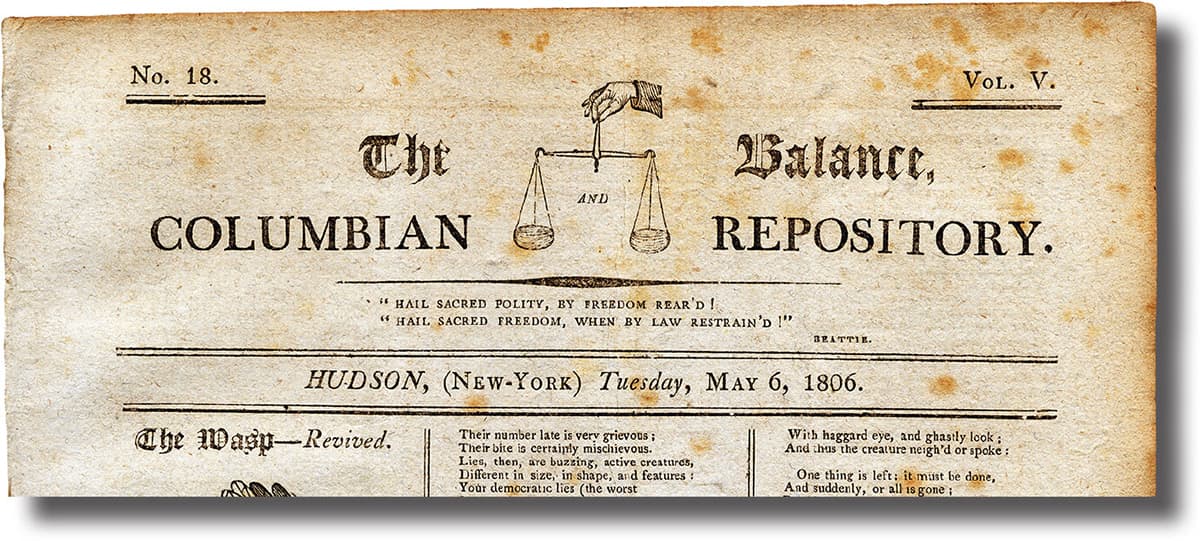

The newly minted cocktail first got noticed when Thomas Jefferson was president. It was cited with barely contained contempt in an 1803 New Hampshire newspaper as evidence of the intemperance of modern urban youth. What exactly this beverage was got defined for the world three years later in a New York newspaper—and not in a particularly positive way there either. The citation noted what kind of drink it was (a “bittered sling”) and then suggested that Democrats who drank them would, under their effects, vote for anyone. Ah, but the real shocker was not spelled out by the definition:

COCKTAILS WERE MORNING DRINKS.

As regularly as times change, human nature stays the same. People were largely outraged at the cocktail much as they remain indignant today about morning drinking.

Drinking in the morning often means getting over what you were drinking last night, and that kind of behavior is what they used to call dissipated. If that wasn’t sufficiently nefarious, cocktails contained bitters. Bitters may sound benign to modern ears, but at the dawn of the nineteenth century, they were medicine. Adding them to cocktails was the equivalent of dousing one’s beer with Nyquil. No one knows for sure how the cocktail got its name, but I am certain it was because they were your wake-up call—like a rooster heralding the early morning light. And its plumage? Those spicy bitters.

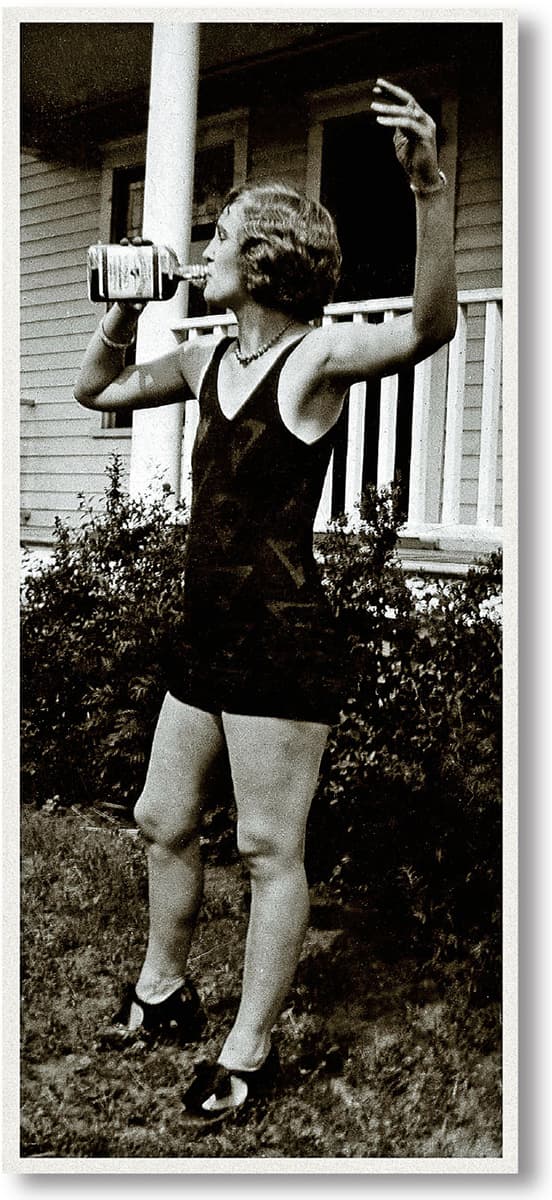

Original flapper photograph, circa 1927

Cocktails were in the realm of sporting men—and by sporting I mean gamblers, hustlers, and protégés of loose women—not baseball fans. And women drinking cocktails? Edgier still. While still roundly eschewed by polite society, the cocktail was becoming steadily more popular. As time progressed, the avenue to more general acceptance made itself evident: the historical equivalent of a tailgate party. Gamblers frequented horse tracks, as did highfalutin horse owners and their hoity-toity offspring and sycophants. To the latter, the sour reaction to the cocktail added a dangerous element that they found very attractive.

If you drank a cocktail, you were a little dangerous, and therein lay the seeds of its fame. It was the bad-boy syndrome.

The economic stature of this group, in our class-conscious society, incrementally tamed the new drink form by making it fashionable. So, by the 1830s, at racetracks and boxing rings, the cocktail baton was passed from sporting men to sportsmen. With that, it began to appear at foxhunts, polo matches, and other superior (more moneyed) forms of morning entertainment.

This is the nature of how all innovations are eventually deployed as bona fide cultural elements. The new is often shocking merely as a result of our phobic resistance to change. Add to that any more specific tweaking of our societal noses (hair-of-the-dog morning drinking, in this case)—and the knee-jerk result is the impression of absolute scandal. It happens consistently, and there is no better example than in the realm of popular music. Violent reactions were had to all of the following genres of music: ragtime, jazz, rock and roll, and rap. Ragtime was considered mindless pabulum; the rest were perceived as savage incitements to sex or violence.

For all its incremental progress, it would be another fifty years before the cocktail got another big leg up, ironically, against the backdrop of the American Civil War.

What happened between those early nineteenth-century newspaper columns and 1862 was the integration of the cocktail, through familiarity, into more general acceptance. By this time, it had ceased to be typecast as a morning drink and was consumed at less controversial hours. Those upstanding curative bitters were now themselves under attack as “snake oil” and sham medicine. Ironically, cocktails now represented their most honest, forthright use. Still, there were no standards of measurement or ingredients, and no pre-eminent cocktails—yet.

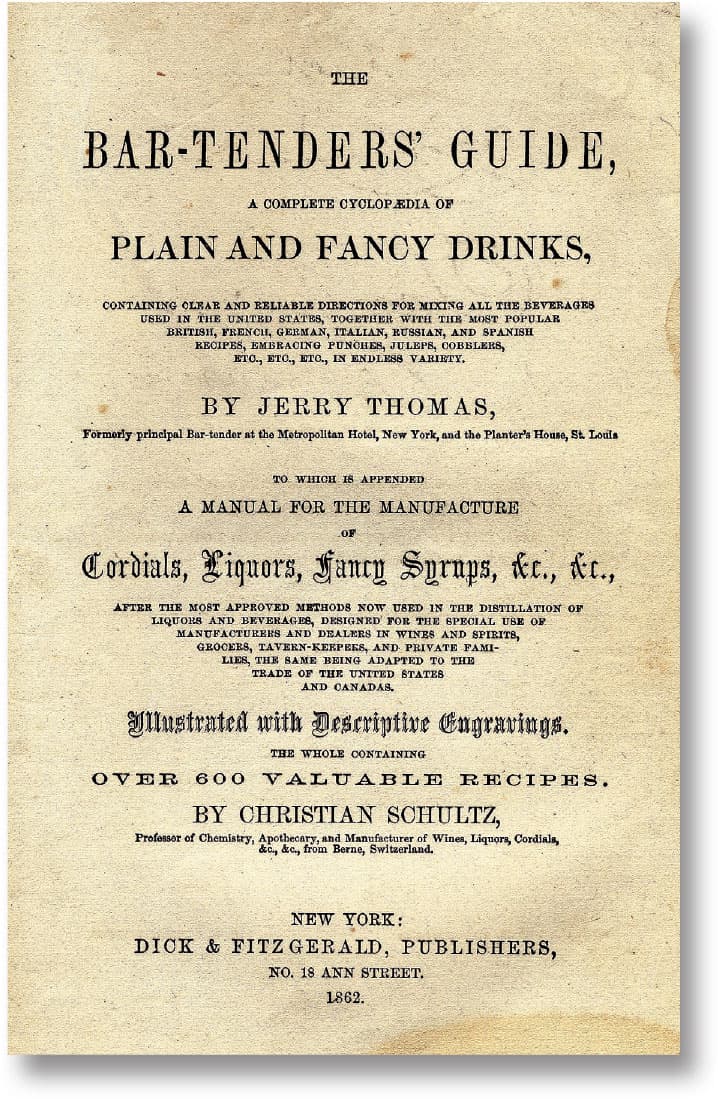

A flashy bartender named Jerry Thomas changed all that when, in 1862, he authored the first bartender’s guide ever published.

Suddenly you stood the chance of getting the same whiskey cocktail at one bar as you might across town, or across the country. A slew of other bar books followed. All of these books were how-to manuals by bartenders for bartenders. They were technical trade manuals, the equivalent of TV repair handbooks. Sure, the general public could buy them, but … why? And as with such specialized texts, what they contained were definitions, directions, measurements, classifications, and subclassifications. The cocktail was merely one of those details, and in terms of mixed drinks, it was hardly the first.

A Mint Julep wasn’t a cocktail, it was a julep. A Sloe Gin Fizz wasn’t a cocktail, it was a fizz. A Singapore Sling wasn’t a cocktail, it was a sling. (Okay, on this last point I’ve taken some dramatic license. There were slings in those days, but not yet anything called a Singapore Sling.) There were also crustas, fixes, sangarees, Negus, scaffas, smashes, cobblers, flips, punches, swizzles, and oh yes, cocktails.

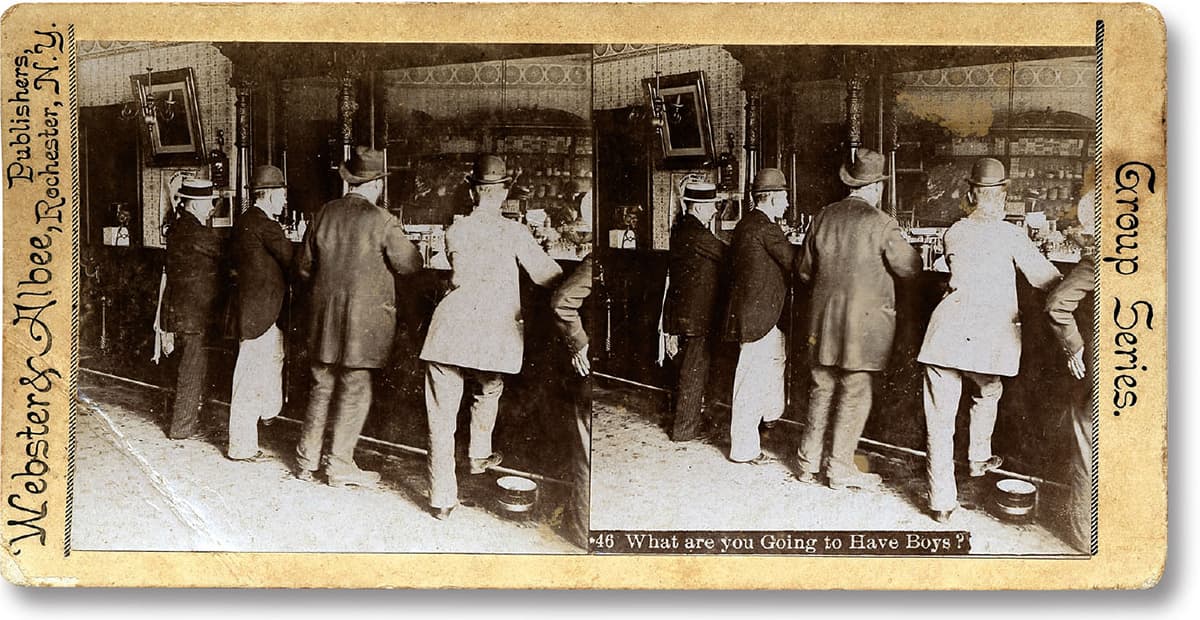

Candid bar stereograph, circa 1886.

All would be considered cocktails today.

Nowadays, we think of practically any beverage made with hard liquor as a cocktail. In those early days, though, that would have been equivalent to proclaiming that all breeds of dog were the same.

Each of these drink “breeds” was made in a slightly different glass or contained slightly different ingredients and combinations of ingredients. Cocktails were booze-of-choice, sugar, bitters, and maybe a dash of liqueur, stirred (or shaken) with ice, and strained into a stemmed glass with, perhaps, a fruit peel garnish. A julep had crushed (or shaved) ice. A flip had egg in it. A crusta had a sugared rim. Punch had fruit juice. The cocktail was not even the patriarch of the family. Juleps preceded it, as did swizzles, possets, slings, and syllabubs, among others.

COCKTAILS, THOUGH, HAD THE BENEFIT OF UTTER SIMPLICITY.

They tasted good and got the job done. Eventually, the formerly shunned cocktail cannibalized the other categories. All hail King Cocktail.

Whoa! Not so fast. There were going to be some major bumps in the road, before cheer leading that level of cocktail veneration.