Part 3

Doing Strategy Mapping (ViSM)

In Part Two, you saw how The Loft Literary Center used mapping to produce their strategic plan for moving forward. In this part you will learn how to do strategy mapping yourself.

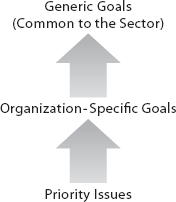

But first, let’s review what strategy mapping can do. The Loft’s experience helps demonstrate that strategy mapping is one of the most productive ways of actively engaging a group in figuring out what to do, how to do it, and why in complex situations when there is no obvious right answer. Strategy mapping, in other words, is what to do when thinking matters. It is a way of replacing what can happen in groups—see Figure 3.1—with what should happen in groups—see Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.1. An Unproductive Group Talking Over One Another and Going Around in Circles.

Figure 3.2. A Productive Group Happily Engaged in Visible Strategy Mapping.

Strategy mapping helps keep groups of people from talking over one another and going around in circles. It helps keep groups from being unclear and confused in their reasoning, unable to listen to one another, and unable to agree. Instead, strategy mapping helps people speak and be heard; produce lots of ideas and understand how they fit together; make use of causal reasoning; and clarify ultimately what they want to do in terms of mission, goals, strategies, and actions. Strategy mapping thus is what is known as “procedurally just,” meaning participants feel they are treated fairly and as a result are more likely to implement agreements. Strategy mapping is also “procedurally rational,” meaning participants see each step of the process as making sense and that therefore the final result is likely to be sensible. Strategy mapping therefore joins process and content in such a way that good ideas worth implementing are found and the agreements and commitments needed to implement them are reached. The result is living strategic plans that act as useful guides to action.

In the following sections we will take you through the steps of developing a strategy map.

Step One: What Do We Have to Change to Create Strategic Success?

Creating an Issue Dump

If you want to change the world for the better (which is what strategic management is about), you must sort out which important issues you, your group, and your organization face that have to be addressed in order to be successful. So, the starting point has to be, What do we think the important issues are?

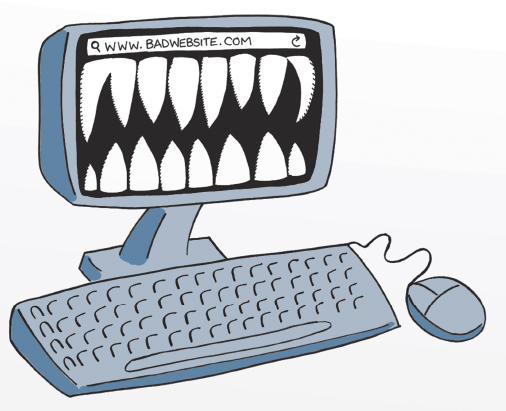

But, what is an issue? Perhaps, one person thinks it is

the website

But this doesn’t tell us much. The statement doesn’t say enough to let us know what the issue is—meaning what has to change. It doesn’t imply what has to be done. For example, one kind of issue is something that is undesirable and requires attention, so that putting “not,” “avoid,” or “stop” in front of the statement will indicate a kind of improvement. Alternatively, an issue can be something positive that someone should do something about, for example, an opportunity that is worth exploiting. In either case, the wording should imply that something is to be done (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. An Unhelpful Website.

In the first case, we might say

our website isn’t good enough

This now tells us what’s wrong and thus implies what has to be changed. However,

people can’t find information on our website about what we do

is more specific. The extra words help express more about the concern. If we add a verb to this last statement, we can get

put more information on the website about what we do

This statement suggests a specific action about exactly what we can do to make change. And just to repeat, strategic management is about doing something to change things for the better.

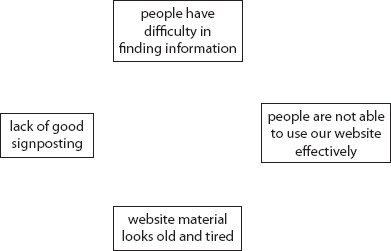

Sometimes two issues are embedded in one statement. For example, someone might say, people have difficulty in finding information and using our website effectively. The “and” indicates two separate ideas. Thus actions taken to help people find information might include, for example, a review of what is available on the website and augmenting it, but those actions may be different from actions taken to make the website effective, such as using a better layout and more appropriate signposting. One therefore should turn the single statement into two statements.

The best way to see the set of issues facing the organization is to write them in rectangles rather than as lists. See Figure 3.4 for an example of an early issue dump related to the website.

Figure 3.4. An Early Dump of Issues Relating to the Website.

Note that because it is useful to change the wording as your thinking evolves, it is helpful to always make the first character lower case. That way you are not discouraged from adding words to the front of what you first wrote.

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Think about something that is bothering you professionally or personally and try expressing three or four issues related to the concern. Scatter the statements around the page. When doing so, try to meet the requirements set out above—namely, give each statement an action orientation by starting with a verb and include only one idea in each statement. Number each statement as you write it. Numbering the statement will help when making links and navigating the map later. Following these guidelines will give you a good sense of what needs to change.

Fran’s Vignette

We authors use mapping all the time. For example, Fran, one of the workbook authors, had just started a new job as dean of research and development for a business school faculty and was keen to use the mapping processes to help her. On the basis of a number of conversations with the previous dean and her new boss, and also with other senior staff on the faculty, she realized that there were a large number of issues and considerations she needed to understand. She also knew that she then would need to start building a commitment among the staff to a new, as yet unarticulated, strategy. Specifically, it became clear that one of her most important tasks was to develop a new strategy for research and development for the business school.

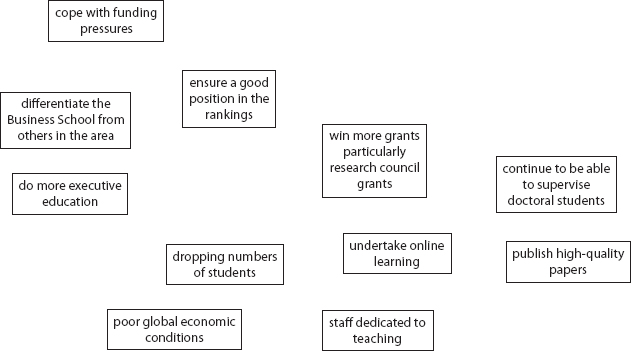

One of the apparent emerging issues focused on ensuring that the school improve its position in the research rankings (a common consideration for many business schools in order to stay attractive to faculty and students) (see Figure 3.5). She believed that managing this issue was one way of helping differentiate the school from others in the area. She was acutely aware that student numbers (including doctoral students) were declining due to global economic conditions. Thus she felt that the faculty would benefit from a concentration on research grants (both from public research agencies and from industry) rather than straight consultancy, as winning grants would both help improve the rankings and would pull in more funds. She also wondered whether improved rankings would also attract more doctoral research students.

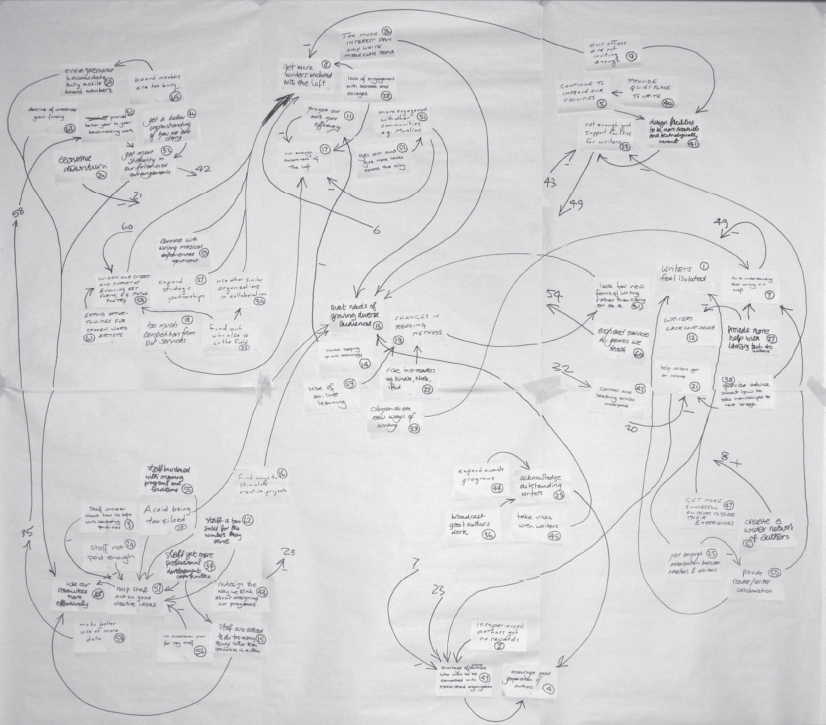

Figure 3.5. Fran’s Initial Dump of Issues.

However, she was aware that a number of staff saw their focus as teaching, as they were dedicated and inspired instructors and reckoned they had little time to devote to research. Also, the school would need to ensure that if staff were to be successful in getting grants, then staff would need to have sufficient time to produce high-quality publications. Of course, if more time were devoted to research, then time would be distracted from working with doctoral students, since there were only so many hours in a day.

In thinking through these issues, she realized that she wasn’t sure a key school administrator was of the same view, since he believed that increasing online instruction was an important way forward. He thought that by providing virtual lectures, for example, they could reach a wider audience. Others in the business school saw that better tapping of the executive education market would be a good way to resolve some of the financial pressures.

While Fran appreciated all of these viewpoints, she worried that there was a danger of not taking a long-term view and considering how the school could sustain its competitive advantage. For example, using online classes might not be a winner, since lots of other schools were considering the same activity. She also wondered how long it would be before they had saturated the executive education market. And then there was the issue of retaining the really dedicated researchers she had in the school. If they felt marginalized, they might leave.

There were just so many things to think about! How could she get her head around the situation? How could she think about the long term but also take care of the immediate pressing issues? She needed to get all of these issues out of her head so she could stand back, see how they fit together, and have a go at figuring out how they might be resolved. She also felt that if she got them out, she could help some of her colleagues appreciate why she was so concerned about the future of the school. She could also then not only build a shared understanding of the interactions between the issues, but also help herself and others explore a way forward. She also knew that her colleagues would come up with some additional issues that she had missed.

She had a full pad of removable self-stick notes (sticky notes), so she started writing the issues down—putting each issue on a single sticky note and positioning it on her office whiteboard. Before long she had twenty-five sticky notes stuck up! What is more, she realized that even more issues could be added. Even so, she felt better as a result of getting the issues out in front of her. Doing so was cathartic. She could now begin to stand back and look at the situation more thoughtfully.

At that moment Alison, Fran’s deputy, knocked on the door for a chat. Fran invited her in and immediately noticed her curiosity about what was on the whiteboard. Fran began to explain what she had been doing. Very quickly Alison grabbed the sticky note pad and started adding issues. The whiteboard began to fill up (see Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6. Fran and Alison Adding to the Initial Issue Dump.

They both began to feel quite excited about what was emerging, as they could begin to see some possible synergies between their points of view, although they were also struggling with what should be included in a joint view and what shouldn’t. Fran wanted to stick to what she saw as strategic issues, but Alison wanted some of the operational issues to be included as well, since they provided valuable context. Besides, she argued, they had an impact on the long-term future—an argument Fran readily accepted! After all, there has to be a strong connection between strategy and operations, or else the strategy is relatively useless. They agreed to use different colored pens to denote which issues were strategic and which were operational. They also found themselves rewriting a few of the issues to help each other make more sense of the statement. They ended up with statements that were between four and eight words long and often explicitly action-oriented.

After about twenty more minutes they felt that they had a good overview of the situation—at least as they saw it—and wanted to get department heads involved. Doing so would help Fran and Alison see what they had missed, and they would also build more of a shared understanding across the whole team. They both felt much better now, since at the very least they understood and appreciated one another’s point of view. They also had a sense of how to make progress. A good hour’s work!

Fran was also aware that she might need to involve others beyond department heads in her deliberations, not just for content reasons but also for political ones. She wanted to make sure that the outcome would be something that all were comfortable with and willing to implement. Careful stakeholder management was critical.

Fran next needed to work out how to manage and make sense of the issues. . . .

![]()

When working with a group it is important to ensure all feel and are able to participate. A well-crafted invitation bringing the group together helps. Once the group is assembled, regularly encouraging participants to contribute their views is therefore important. Making contributions will help each participant feel he or she is part of the process and likely will build emotional as well as cognitive commitment to, and support for, any strategies that are developed.

More immediately, however, participation will help develop a wider appreciation of the situation and a more robust view as people contribute actions, and their explanations and consequences are captured. Of course, participation can be encouraged as part of a commitment to a more engaged and inclusive workplace or broader democracy by a public and nonprofit organization. When there is not such a general commitment, participation can be quite useful for the very instrumental reason of increasing the probability of implementation of strategy.

Following is another example of an issue dump, this time involving a health care organization.

Health Care Vignette

The senior management team of a health provider (part of a larger managed health care system) was reviewing their strategy after having received two fairly negative external reports. The team started by generating issues on sticky notes and attaching them to a flip-chart-sheet-covered wall. This allowed participants to vent some of their frustrations, but more importantly helped them get an appreciation of the myriad issues facing the team. Getting clear about the issues would also help the team determine which ones to address first.

Relatively early in this process, one of the participants put up an issue stating “we need to improve our HR (human resources) services.” The HR representative immediately felt under attack. She appreciated that there were gaps in the service and the speed of response wasn’t that great, but the demands on her small group were significant and there simply weren’t any additional resources available. The others didn’t understand the difficulties she was facing! The HR representative stopped writing up issues and began to withdraw from the process.

The senior manager on the team noticed the HR representative’s withdrawal and slowly was able to draw her back into the group. He asked her to write up a number of issues that she thought explained the poor service, such as “lack of adequately trained staff,” “too few staff,” and “all departments wanting answers at the last minute rather than giving the HR department enough time to provide a thoughtful answer.” As the HR representative put them up on the board, two things happened. First, she felt better because she could explain why the services weren’t great, and second, other participants began to appreciate her situation and how difficult it was. There were comments such as, “Oh, I didn’t realize that you were struggling with lack of staff” and “Yes, we are rather last minute, aren’t we?”

The team now needed to see what they could do with the issues. . . .

![]()

Two important lessons may be drawn from this short vignette. First, to keep the strategy conversation open and engaging, encourage those contributing the statements to avoid prescriptive words as much as possible, This will reduce the chances that someone will feel attacked and become defensive. Encourage participants to avoid using the words need, ought, and should. Instead, ask participants to phrase the issues so that they are possible or proposed actions. Phrasing issues as actions can engender a more creative, open, and accepting spirit.

Second, encouraging others to respond with explanations and other perspectives, rather than just disagreeing, often softens what can feel like harsh or uninformed views. Using a “round robin” contribution process can help, since this will ensure that all are given a fair voice without continual interruptions.

Beyond the reasons here, continually provide reassurances and encouragement to the participants and prompt them to make further contributions that both support and contradict issues. This will stimulate a more comprehensive issue-capture process. Make sure there is both time and opportunity to place apparent criticism in a wider context. It is important to keep participants involved and the process open because the real issues facing a group are often sharp, critical, and even threatening, and without thoughtful facilitation they often simply get washed over by politeness or worry about the consequences of raising them.

Bundling Issues Statements into Clusters

Moving the statements into clusters held together by a common theme or subject matter helps make sense of the unfolding material and provides an initial overview of the material. Creating clusters with clear white space (on a whiteboard or flip-chart-sheet-covered wall) between them makes it easier for participants to absorb the material since they can concentrate on one cluster at a time. Clustering can help identify issues that might be missing from a cluster.

Fran’s Vignette Continued

Recall that Fran and Alison had captured their issues on a whiteboard and Fran next needed to work out how to manage and make sense of the issues.

Later on in the day, while reviewing the picture on the wall, Fran realized that there were a number of clusters representing different themes within the material that she and Alison had identified. For example, there was a cluster of material around gaining grant funding and another around ensuring teaching quality remained high. She began to move her sticky notes around to reflect these common themes. Some of the clusters were quite large and others were quite small. Did this mean that she hadn’t considered the smaller clusters enough? Should there be more statements in these clusters? Should she add more?

She needed to play with the clusters and get a feel for the different strategic themes that were emerging. . . .

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Practice what Fran did. Think about what’s on your mind. What issues have you been thinking about? Build upon your earlier issue dump and capture more ideas.

Once you have generated all of the issues that come to mind, see if there are any emergent clusters and move the sticky notes so that they clearly reveal these clusters.

Step Two: Why Change the World?

Changing your world for the better—that is, engaging in strategic management—means that you must sort out which important issues have to be addressed by you, your group, or your organization in order to be successful. You must also be clear about the purposes and priorities to be served by addressing these issues in order to provide a focus for effectively expending energy, financial resources, staff time, political capital, and other commitments. Recall that one important view of strategy is that it is about purpose and the prioritization of energy, emotion, cash, and so forth to achieve those purposes.

Sorting out the issues means you need to know how working on one issue may have an impact on other issues. This means identifying the causal links that indicate what leads to what—in other words, means-ends relationships.

To clarify means-end relationships, asking, “How we can change things, and what are the consequences of changing them?” can help in understanding these causal links.

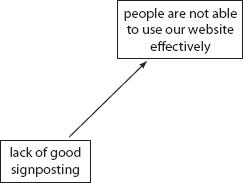

But what is a causal link? One member of the group might say, “People are not using our website effectively because there is a lack of good signposting.”

Alternatively, someone might say, “We need more signposting, because people are not able to use our website effectively.”

In both cases, the person is arguing for a causal relationship, or link, whereby improving the website is achieved by making navigation easier. The link expresses a means-ends relationship in which navigation is a means to the end of improving the website.

Entering Causal Links

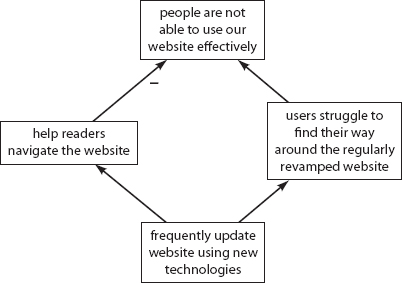

An arrow is used to represent the causal link. The arrow implies “may lead to” or “may cause” or “might result in.” For example, in Figure 3.7, the arrow indicates that the lack of good signposting leads to or causes people are not able to use our website effectively.

Figure 3.7. Causal Links Are Shown by an Arrow Leading from a Means to an End.

In this case, the means or cause of “lack of good signposting” is believed to lead to the end or outcome of “people are not able to use our website effectively.”

Of course, there is a danger of having the arrow point the wrong way and thus not express an action leading to a desired outcome. For example, when we want to show a means-ends relationship, the arrow should go from the means to the end. Thus, in a chain of arrows, the bottom of a chain of arrows (the first statement in the chain) is the first action, or “means,” and leads to an outcome, or “end,” which in turn becomes the action or means leading to a second outcome or end, which then becomes the action or means leading to the subsequent outcomes or end, and so on up the chain to increasingly higher-order outcomes. In essence, a chain of argument is created around mean-ends relationships.

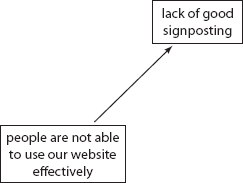

It is easy, however, to get the direction of arrows wrong by confusing chronological relationships with causal relationships. For example, consider the statement concerning effective use of the website: someone might code people are not able to use our website effectively so that there is lack of good signposting (see Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8. Example of an Inappropriately Coded Link.

In this case, the inappropriate coding illustrates chronology rather than causality.

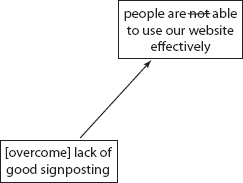

The link is now expressing the idea (link) that because “people are not able to use our website effectively” we therefore need to “[overcome the] lack of good signposting.” It seems logical because the “need” is the driver. But our map should consist of statements linked to show actions leading to outcomes, or means to ends, rather than needs leading to actions. The arrow therefore should go from lack of good signposting (the means) to people are not able to use our website effectively (the end). Said more positively, we overcome the lack of signposting in order for people to use the website effectively. The means causes the desired end. Remember, strategic management is about taking action to change the world in desirable ways.

Alternatively, thinking in terms of if-then statements can help get the causality right. For example, if we “[overcome] lack of good signposting,” then “people [will be] able to use our website effectively.” Note as well that avoiding using prescriptive words, as discussed earlier, can also help prevent us falling into the trap of using chronological links rather than causal links. For example, look at Figure 3.9, in which some rewording helps us get the causality right.

Figure 3.9. Rewording of the Issue Statement to Reflect a More Action-Oriented Language.

This rewording can help ensure more of a “let’s change the world” perspective.

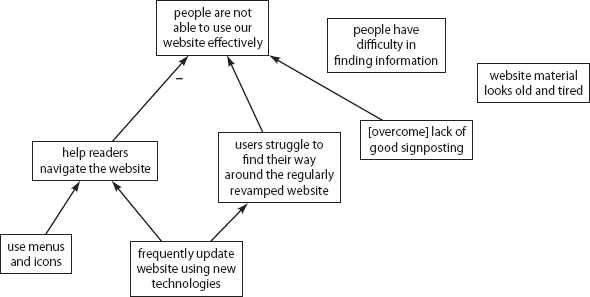

As we try to establish what causes what among the issue statements, we will often see that an issue statement has been written so that it really consists of two statements that are causally linked. For example, see Figure 3.10.

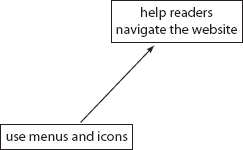

Figure 3.10. Example of One Statement That Needs to Be Split into Two Causally Linked Statements.

In this statement, the word to implies causality, meaning we want to “use menus and icons” in order to “help readers navigate the website,” so we have two statements that are causally linked. In Figure 3.11, you will see that the two statements have been split and causally linked.

Figure 3.11. The Same Statement Split into Two Causally Linked Statements.

Why is it so important to pull the single statement apart? The reason is that menus and icons are two separate means of helping readers navigate the website. If we didn’t pull the statement apart, we would likely miss asking ourselves whether there are other possible options to navigate the website.

Something else to keep in mind is that sometimes an issue can have a negative impact on another issue. For example, people are not able to use our website effectively will have an adverse effect on getting more people to use our products and services.

Where this is the case, a negative link is used. Negative links are represented with a small minus sign at the head of the arrow. The negative link does not imply a negative outcome but rather that the outcome of an action is the opposite of what has been written. Therefore people are not able to use our website effectively would lead to NOT get more people to use our products and services. Sometimes a dilemma might arise when an apparently attractive action option has both negative and positive consequences—meaning some of the arrows out of the option will have negative signs on them and others not.

In Figure 3.12, the suggestion frequently update website using new technologies can have the positive benefit of help readers navigate the website and thus negatively link to people are not able to use our website effectively, BUT if done frequently (possibly due to adopting all the latest technological advances), then users struggle to find their way around the regularly revamped website, thus resulting in them being not able to use our website effectively. The dilemma shows both the dangers of updating too frequently and the advantages.

Figure 3.12. Example of a Dilemma Created by Having Both Positive and Negative Arrows Lead from an Action to an Outcome.

Health Care Vignette Continued

Recall that the team had surfaced a number of issues and was beginning to understand one another’s perspectives better—they had clustered the material and were exploring the clusters in more detail.

The health services team was reviewing the cluster relating to staffing. One of the issues within the cluster was the lack of appropriate training (the patient demographics had changed, resulting in nurses having to deal with challenging patient cases). They noticed that this issue linked both positively and negatively to the issue relating to ensuring high-quality patient care—thus illustrating a dilemma. If they sent staff on training courses, then ultimately they would have better-quality staff and ensure patient care. Unfortunately, in the short term they would be short of staff (because the courses weren’t offered very often and also were in another location, so staff would have to spend several days at a time out of the service), resulting in poor, rather than good, patient care. They therefore needed to manage the training carefully! This observation gave rise to a number of suggestions for potential actions—such as, for example, taking on some short-term contract workers—which helped elaborate the map further in an attempt to resolve the dilemma.

The group began to realize that they needed to capture some of the links between the issues. . . .

Extending the Causal Chains by “Laddering Up” and “Laddering Down”

The process of offering explanations is “laddering down” a chain of argument, with arrows always pointing from an explanation to its consequence, or an action to its outcome. Likewise, the process of exploring consequences is “laddering up” by building chains of argument going up a hierarchy. In the health care vignette, laddering down to provide explanatory issues had helped build a shared realization that the HR manager was hardly stupid or incompetent; instead, there were very good reasons why what many assumed were easy things to do could not be accomplished. More specifically, the HR department was overwhelmed both by the behavior of others (including those who might have thought the HR manager was stupid or incompetent!) and because of resource limits. Bringing these explanations to the surface meant something could be done about them. Leaving them unsaid and unaddressed would cause needless frustrations and inaction or, alternatively, might lead to making agreements that are unrealistic because constraints have not been made explicit.

Also note from the health care vignette that the HR manager had, in expressing her views, written “all departments wanting answers at the last minute, rather than giving the HR department enough time to provide a thoughtful answer.” Including the expression “rather than,” as she did, can be very helpful, because it provides a better understanding of the meaning of “last minute.” Thus issues gain additional meaning from their context—that is, from the statements linked in and out of them and from their explicit or implicit contrasting elements. Participants therefore should be prompted whenever possible to articulate contrasting aspects of an issue as a way of helping increase the understanding of an issue.

When linking the material within and across the clusters, it is helpful to move the material in the clusters into a hierarchical structure that places those issues relating to very broad and overarching considerations—which are often very strategic and more general outcomes—at the top of the hierarchy and those issues that are more detailed and specific—which are more likely to be operational issues—farther down. The hierarchical arrangement helps ensure that resulting links drawn in show a relatively neat flow up from issues that are more detailed means to issues articulating broader ends. See Figure 3.13.

Figure 3.13. Building a Hierarchically Arranged Cluster by Moving Broad Issues to the Top and More-Detailed Issues Farther Down.

In this case, some links are already drawn in. This tidying up process also helps identify dilemmas and will also be useful when considering some of the analyses.

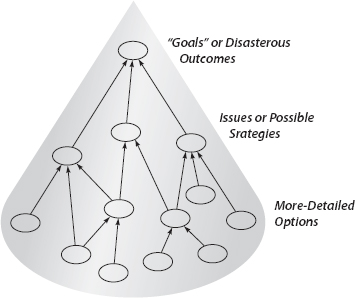

When the laddering up includes goals and negative goals (that is, undesirable outcomes or consequences that are at the same general position in the hierarchy as goals), the resulting hierarchy will begin to produce clusters that take a fairly generic “teardrop” shape (see Figure 3.14). The teardrop fans out from the goal to include issues that will need to be addressed in order to achieve the goal. Each issue, in turn, fans out to include an array of options that might be chosen to address the issue. When specific issue options are selected, the issue in effect becomes a strategy for achieving the goal.

Figure 3.14. The Structure of a “Teardrop.”

Source: Eden and Ackermann, 1998, p. 236.

Health Care Vignette Continued

The health care group members were exploring some of the dilemmas emerging from a review of their clusters.

They were becoming more engaged with the process and enjoying linking the material. As the conversation about positioning the statements on the wall unfolded, it revealed some interesting differences in viewpoint about some of the links.

For example, members of the group gently challenged proposed links by asking for further clarification regarding their rationale. The ensuing explanations not only generated further issues (as a chain of argument was elaborated), but also prompted others to provide their alternative points of view, which were also added to the developing map. For example, when discussing how get more beds linked to provide better patient care, an additional issue—determine best pathway for the patient—was added. This was because the statement’s contributor believed just getting beds wasn’t enough, since in many cases have patients stay at home would be better. What the health services unit needed to do was think about patient pathways. This triggered another group member to note that if that was the case, then that would help clarify who we need to work with as the patient pathways would certainly involve getting contributions from other specialists such as dieticians, physical therapists, and so on.

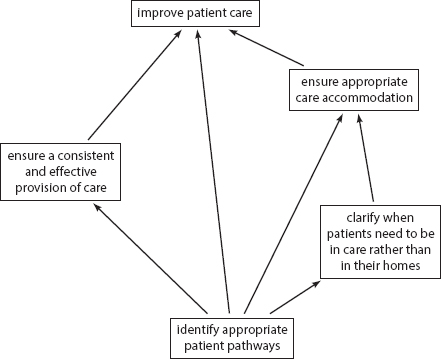

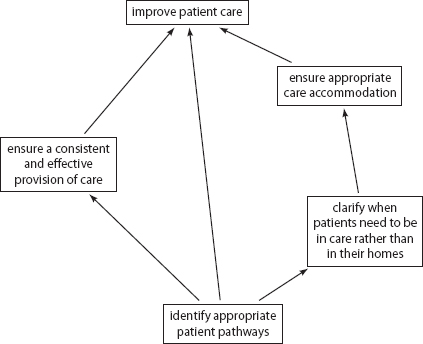

After about an hour and a half of work linking and reorganizing their material, the health services management team went for a coffee break. They felt good about what had been achieved. However, while considering their progress and what had emerged over coffee, one member of the group observed, while looking at the map, that in the process of linking they seemed to be repeating themselves, which he thought might explain why the map seemed to look unnecessarily messy. For example, he noticed that there was a chain of argument linking an issue both directly and indirectly to another issue and wondered if both chains of argument were needed. In other words, was one chain redundant because it was a summary of the more detailed links (see Figure 3.15)?

Figure 3.15. The Health Care Example Showing Redundant Links.

Two other members of the group caught on immediately. As one of them noted, “We have identify appropriate patient pathways linking to clarify when patients need to be in care rather than in their homes, which supports ensure appropriate care accommodation and thus improve patient care (in essence A → B → C → D), but we also have identify appropriate patient pathways linking directly to improve patient care (A → D) and identify appropriate patient pathways linking into ensure appropriate care accommodation (A → C).” He questioned whether they needed these extra links. His comment got a lot of responses. One of his colleagues said, “Well, identify appropriate patient pathways does help us improve patient care as it will ensure a consistent and effective provision of care.” Then he laughed at how he had inadvertently illustrated the essence of the query and noted that this extra statement had already been captured (A → E → C). However, another colleague noted, “We don’t need the link between identify appropriate patient pathways and ensure appropriate care accommodation—that is covered through the link to clarify when patients need to be in care rather than in their homes—we should take that out” (see Figure 3.16).

Figure 3.16. The Health Care Example with Redundant Link Removed (contrast with Figure 3.15).

The health services group now wanted to think about what these clusters suggested for their strategy—how did they relate to the goals. . . .

![]()

It is worth noting that the tidying up of links needs to be done carefully as there is a balance to be had between refining the structure to allow for managers to be able to distinguish interesting insights from the map’s structure with pruning too radically and losing richness and ownership. Remember there is always the balance between procedural justice (including the views of all) and procedural rationality (developing a tight structure).

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Step Three: Making Sense of Your Map

As we can see, issues don’t exist in isolation from one another. When statements are linked together, a different appreciation of the situation will emerge. The emerging causal map helps ensure that strategic actions meant to manage one issue will not also exacerbate or confound another issue (see Figures 3.17a and 3.17b). By understanding what is meant by particular issues, it is easier to determine options to resolve them. For example, the issue of patient care noted in the health services example is one all can agree upon, but unless there is agreement on the issues surrounding it, and how they might be resolved, it is possible that actions being taken can confound one another and progress can be impeded.

Figure 3.17a. The Paddlers’ Opposing Actions Confound Each Other.

Figure 3.17b. The Paddlers’ Complementary Actions Facilitate Progress via Alignment in Direction of Energy.

The developing map also helps reveal where there may be gaps in one’s or a group’s understanding of the situation.

Typically, there are a lot of issues on a map, and it is important to be able to make sense of all the material and subsequently focus on where to prioritize taking action. Given that strategy maps are causal networks, they can be navigated in a manner similar to a road map. Maps can be as big as several hundred contributions, which is not surprising if we are involving a large number of people in the process and are taking a broad organizational perspective. With any map, and particularly large maps, some method for focusing on what is most important is crucial; otherwise it would take many days to check all of a map in detail.

As noted earlier, initially the issues can be clustered in content-oriented themes. For example, a theme might capture all the issues relating to training. When within- and cross-theme links are created, however, the themed clusters are no longer discrete entities and theme-specific content is not the most appropriate way of making sense of the material. Instead, as the statements from one cluster are linked to statements in other clusters, the material becomes clustered in new ways through inter-cluster means-ends relationships. The resulting strategy map is now becoming a strategic change model. The “new” map can help participants engage with a big causal picture and figure out how to manage the messy interrelatedness of issues. Said differently, a key objective for the group now becomes figuring out how best to use the causal chains to understand what to do, how to do it, and why, and thus to manage change effectively.

But first, some tidying up typically is needed. As noted, issues typically do not relate just to the other issues in their particular original thematic cluster. They also relate to issues in other thematic clusters. This reflects the interconnectedness that abounds in an attempt to develop strategies to affect how organizational or other systems work. Because issues don’t act in isolation from one another, a causal map typically can become quite messy, as links appear to go all over the place. Reorganizing the map almost always helps, and restructuring the issues according to their links (rather than according to the initial themes) will give different insights.

In addition to different insights from the resultant “tidied up” map, a better sense of priorities and where to focus energy typically emerges. As one public-sector executive director noted, “I have more initiatives than I can wave a stick at. What I need is a better sense of where the priorities are!”

There is a danger, of course, that when a group looks at a complete causal map, only issues that have “noisy owners” will get prioritized. A useful way to avoid this situation is to engage the group in a rough analysis of the structure of a map. Understanding the structure of the map and the connections between and among the issues helps the group determine which of the issues:

- Are central in the network, and therefore affect the most other issues

- Are relatively peripheral, and therefore are likely to be more marginal

- Offer high leverage in terms of achieving desired outcomes

- Contribute to solving the most, and the most important, issues

Exploring these properties of the map allows for a more considered understanding of where priorities might be established. The analysis usually can provide some sort of guiding basis for negotiating agreements on how to proceed.

So Where Do We Start? Let’s Begin Making Sense of the Map!

As we noted earlier, once the group has captured all of the issues and links as they see them, it is important to take stock of what has emerged. An important part of taking stock is getting a sense of what is urgent versus what is important, what is central versus peripheral, and so forth. Making sense, however, can be difficult if the map remains quite messy.

One way of creating a less messy initial causal map is to avoid drawing in long links by instead drawing in a short arrow that does not go to the distant statement to which the first statement is linked, but instead points to the number of the statement written in at the end of the short arrow. For example, if issue statement 45 was to link to issue statement 23 (on the opposite side of the map), a very short arrow from 45 with 23 at its head would capture the link without the need for someone to draw the long arrow (see Figure 3.18). Likewise, a short arrow linking the number 23 (not the actual statement) with statement 45 at its end also should be indicated in order to ensure that the 23 → 45 link is retained no matter where attention is focused (see Figure 3.18). However, while this is apparently less messy, it can impede a group’s ability to see the emergent structure and some of the interesting insights that result. This is why “tidying up” by remapping the material onto a new mapping surface can be helpful. To do so, however, a break in the workshop (perhaps for coffee) usually will be required so that the facilitator and one or two participants can do the remapping.

Figure 3.18. “Long Links” Can Be Avoided by Having Short Arrows Come from or Point to the Number of Another Statement.

Photograph repeats Figure 2.8, showing the map after the group had added links (note that Paul has put in a “solid” arrow in the upper center to show the merging of several arrows).

Another way to manage the process of remapping is to start by focusing on the issues that appear to have the most links around them, that is, with the very “busy” issues (see Figure 3.19). Move the sticky notes that are the busiest issues to the new mapping surface first and then bring with them the issues immediately supporting them, meaning those that link into the focal issue. Before doing so, however, make a duplicate sticky note for each busy issue and place the duplicate one on the original mapping surface in the place where the original was so as to retain the memory of the initial structure and to avoid losing links. Next, bring those issues that are consequences (links out) of the focal busy issues. Starting the remapping process with the busy issues reflects their centrality in the map and can often quickly produce interesting insights.

Figure 3.19. A “Busy” Concept Has Many Links In and Out.

Transit Vignette

A city-owned transit organization’s management team was reviewing their issue map, and they were somewhat astounded to see that one of the biggest causal clusters was related to communication. It had thirty-five issues! They recognized that communication was a key strategic issue, but the sheer volume of material connected together around this topic was quite a surprise. They hadn’t thought it was such a big deal.

How were they to manage this issue? As they began to review the issue’s contents, they realized there seemed to be sub-clusters relating to audiences. For example, there was a causal bundle of issues relating to communications within the organization itself, as well as another causal bundle of issues relating to communications with other transport providers (for example, other bus companies, taxi companies, and so on). And then there was another bundle of issues relating to communicating with the public. Suddenly they began to realize why some of the previous initiatives relating to communications hadn’t been too successful—they were assuming one approach to communication would suit all purposes!

The group began to break down the big cluster into the small sub-clusters and restructure them with the most superordinate issue statements at the top. They knew they had to be careful because they didn’t want to lose any links. One team member suggested taking a photo. That way they would have a record. This was quickly done. Another member of the team then suggested that if they put up more flip chart paper and moved the sticky notes, they wouldn’t need to rewrite the statements, but they could use a small blank sticky note with just the reference number on it to replace each statement as it was moved from the original map to the redone map. That way they would retain the original map’s network structure.

![]()

Another useful aid to understanding and navigating the map is, with the group’s help, to label the new causal clusters (perhaps using a different color sticky note to distinguish it from the other sticky notes). As with some of the issues on the original map, some of the causal clusters will be more central than others, with some clusters being well connected to issues in all, or virtually all, of the other clusters. Other clusters typically will have only a small number of connections to other causal clusters.

Fran’s Vignette Continued

Fran and Alison had generated a lot of issues, and Fran had done some rough clustering and was keen to identify the strategic themes emerging, but she needed to do some tidying first.

She was reviewing her map and moving the issues around to further tidy up the map. After taking a quick photo, she had identified the busiest issue and put it in the middle of a flip-chart-sheet-covered wall space that she had put up alongside the whiteboard. She made careful note of where on the whiteboard the busy issue had come from. She continued to move material across, but found it difficult at times to get the structure into a perfect hierarchy. She tried hard not to have links crossing over one another, but sometimes it simply wasn’t possible. She was beginning to realize why she had found the situation she was facing so complex. Not only were there a lot of issues, but many of the issues had multiple explanations and consequences. The interconnected statements formed a “system” of highly interconnected issues.

When she finally had a tidied structure, she liked the look of it. Its shape and the links indicated interesting properties. Standing back she was amazed to see that a couple of the issues she had thought were really significant actually were pretty inconsequential. They simply didn’t have many links to other important issues. She realized that she had been wasting some of her energy by focusing on some things that just weren’t very big deals. She felt relieved, freed up, and energized by this insight.

Next she had to understand what impact the issues had on the faculty goals, but before doing that she had to find a time for getting all her team together. . . .

![]()

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

As noted, it can be very useful to rearrange the clusters to move away from content-oriented clusters to causal clusters. Now have a go at doing that exercise with your sticky notes.

Making Sense of the Overall Map: What Can We Learn from Our Map?

Creating causal clusters usually provides valuable help in making sense of the big picture. Additional insights can be gained by exploring the structure of the map. Useful structural characteristics to look for comprise finding “orphans,” exploring goals, identifying central issues, and identifying feedback loops. The first two are discussed here; the third and fourth are discussed later.

Finding “Orphans”

Orphan issues are those issues that are not connected to another issue statement. They currently have no in- or out-arrows. Sometimes orphans are genuine—they are isolated issues. More often the connections simply got missed when the group was putting in causal links. Locating orphans usually helps tighten the map’s structure through identification of missing links.

Exploring orphan clusters will lead to similar considerations. Are any of the clusters not connected at all to the other clusters? Again, this might mean that links have not yet been identified. However, it might also mean that the issue cluster is a totally separate issue area and thus is worth considering in its own right. It may well be an issue that will need to become a priority, with some prioritized agreed-upon actions toward the bottom of the cluster hierarchy.

Exploring Goals

As is the case in most strategy work, understanding the organization’s goals (its purposes) is important. Clarifying purpose is important for all organizations or multiorganizational collaborations, whether they are large or small, government department or agency, or a nonprofit organization. Goals are what the strategies aim to achieve, and they provide an overall sense of purpose for the group and organization. Each organization has its own preferred terms identifying purposes—for example, goals, objectives, aims, and so on. Arguing over the fine points of terms is, in our experience, generally a waste of time. It is, however, important to use the terminology that the group is comfortable with while also being clear about what the label means to the group.

A goal or a statement of purpose can be seen as something that is good in its own right. The group would want to aim for it almost regardless of anything else. For Fran, as dean of research, and for her faculty, a goal thus might be to “become recognized as excellent at research,” or for a local community-development team it might be “ensure a safe environment within which to live.”

A good way of teasing out goals or objectives is through exploring why issues are issues. People only identify issues as issues if they either support or undermine their important goals or values. These goals may never have been made explicit. Supporting a goal means the issues highlight opportunities that might contribute toward achieving a goal. Undermining a goal means the issues pose threats that can negatively affect goal achievement, perhaps making the goal difficult or even impossible to achieve.

To start identifying goals, identify those issues that are at the top of a “teardrop.” Teardrops are a hierarchically organized network of causally related statements with a single topmost statement, intermediary statements linking into it and a number of statements at the bottom of the network (shaped like a “teardrop”). This is different from clusters, which are either content-oriented clusters (a bundle of material that is in some way tied together through a common content-related theme, or by a dense set of causal links) or causal clusters (a relatively small network of statements and causal links that represent an “island” of linked material with relatively few links to other causal clusters) as they focus on a single point.

These top points are frequently heads—that is, statements with arrows coming into them, but with no arrows coming out. Sequentially look at each of the heads and ask yourself and your group, why is this issue an issue? Why does it matter? What would the consequences be of addressing this issue? Answering these questions either will result in laddering up to a goal or else will surface one or more further issues that then lead to a goal. (Do note, however, that the “goal” may be worded as a negative, for example, “we go bankrupt,” which would count as a negative goal. In addition, since issues are often “problems,” they may detract from goal achievement. In this case, the link would be a negative one leading to the goal, meaning that the issue may lead to not achieving the goal. In the end, of course, you will want to have mostly positive goals to strive for, as well as perhaps some negative ones to avoid. More on these possibilities will be said later.)

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Try laddering up to the goals so you understand better why the issues concern you and others and what your goals in practice are (rather than those goals that are just rhetorical). (See Practice 5.)

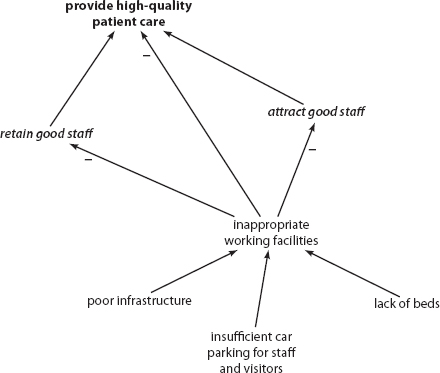

Health Care Vignette Continued

Following their coffee break—a reward for sorting out a number of the clusters—the health care group got back to sorting their issue map, thinking about what their clusters suggested for their strategy. How did they relate to the goals?

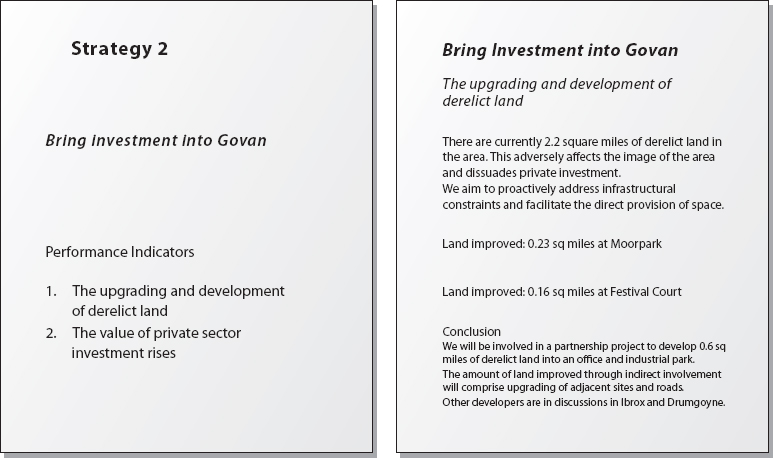

The group noticed that inappropriate working facilities was at the top of a cluster. It had lots of issues linking in, such as insufficient car parking for staff and visitors, lack of beds, poor infrastructure, and so on. To see if it was a goal—something that was good in its own right—they tried converting the language to something more positive and aspirational—for example, develop appropriate working facilities. (The “positive” statement might also be created by adding stop, avoid, or not, if this wording captures a more realistic aspiration.) While the group agreed that they should capture the statement develop appropriate working facilities, they didn’t see that as being a goal. It was more of a means to a goal, which meant that it was a possible strategy or even an operational action.

Following this conversation, they asked themselves what they would achieve by overcoming inappropriate working facilities. Two particular outcomes immediately came to mind: the first was provide high-quality patient care and the second was attract and retain good staff. After some discussion, they agreed that providing quality patient care was a goal and something to aspire to; they were less clear, however, about whether attracting and retaining staff was a goal or just a means to an end. The idea of attracting and retaining staff suggested two strategies, since keeping good staff was different from gaining new ones. Both strategies in turn would help in achieving the patient goal. The resulting structure began to look like the one in Figure 3.20.

Figure 3.20. Example of the Health Care Organization Laddering Up to a Goal.

The group continued to explore the consequences of inappropriate working conditions before moving on to other “head” issues or issues at the top of a teardrop and laddering up from them. Before long the group had about fifteen candidate goals. They now needed to consider carefully how these goals related to one another.

They also knew that the next step would be to begin to prioritize where to focus their energy, as they would not be able to address all of the issues. . . .

![]()

In laddering up, sometimes the consequence of the issue is worded negatively. For example, when exploring the consequences of reduced funding, a city might find itself having to reduce services and thus not be able to achieve the goal of, for example, presenting itself as an attractive tourist destination. The link between the issue relating to reducing services would therefore negatively link to the goal of presenting an attractive tourist destination. However, it is also possible that in laddering up negative goals may emerge. These are ramifications for which converting them into a positive frame would not be seen as a realistic goal. For example, as a result of the issue of too few staff, there is the consequence of stress and burnout in staff. The group might agree that stress and burnout must be avoided at all costs. Converting this negative goal into a positive, namely avoid stress and burnout in staff, is unlikely to gain much attention. However, rewording the statement in this “positive” yet still rather negative way might prompt participants to generate a goal that says provide an enjoyable environment within which to work. The process of considering rewording the negative goal thus facilitates the generation of a new goal.

Once the laddering up from all “heads” of teardrops is complete and draft goals are identified, it is time to begin to explore how the goals relate to one another. It is unlikely at this stage that there are no connections across the multiple “ladders” that have now been created. Spend time considering how goals have an impact on one another.

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Build the goals system for the interlinked issues area you have been working on. This will clarify the purposes of the organization.

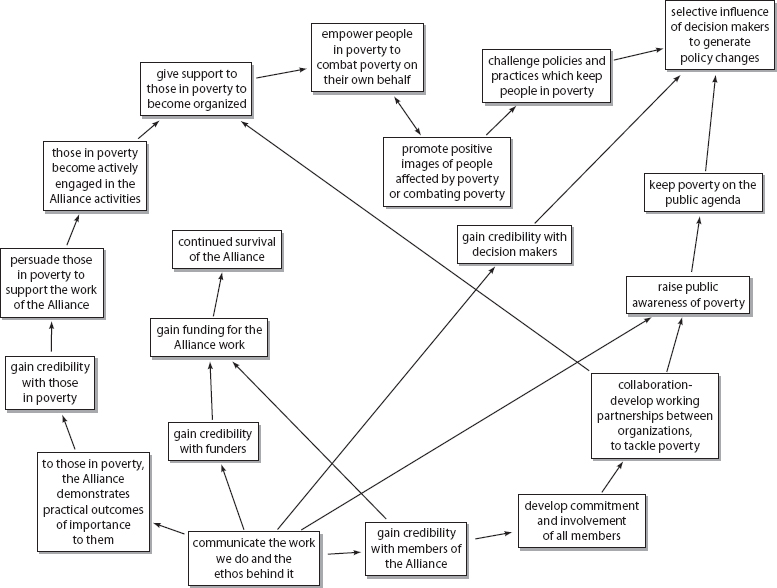

Anti-Poverty Vignette

The top management team of a nonprofit alliance (a multiorganizational collaboration) focused on reducing poverty had just finished identifying their goals and were reviewing the system of goals they had created. They were surprised, and interested, to see that there were two dominant chains of goals (out of three) (see Figure 3.21).

Figure 3.21. The Draft Goals System for a Nonprofit Anti-Poverty Alliance.

Source: Eden and Ackermann, 1998, p. 252.

The first chain targeted policy makers and comprised goals relating to working collaboratively with other organizations, growing public awareness, and influencing policy makers. The second chain of argument concentrated on goals relating to working with those in poverty and encompassed goals about gaining credibility with this population, giving support, and empowering those in poverty. The team appreciated that two of the alliance’s most important stakeholders had goals addressed toward them.

The third chain, however, was the one that they were most uncomfortable with. This chain focused on gaining funding in order to make sure the alliance survived. While this was of paramount importance, if they were going to be able to stay in business and continue the work, it seemed illegitimate at first to have this as a goal. On reflection, however, they concluded that it was in fact a very real and salient goal and one that they needed to work toward.

Perhaps most significantly, the group realized that their goals demanded totally different skills from staff members. In other words, the skills for influencing policy makers were completely different from the skills needed to work with those in poverty. Appreciating these two almost opposing strands of purpose was a real breakthrough for the group, and would not have surfaced without an exploration of the structure of the goals as a system of interconnected goals. The group did, however, need to discuss whether some goals might be purely for internal purposes and not disseminated to a wider audience.

![]()

Once the goals system has been developed from the issues, it is worth considering how it stacks up against existing goals and whether the existing goals should be added or not. In many organizations the goals that are publicly espoused are different from those used in practice, and it is worth exploring the connection between the two views of purpose. This exploration may lead to a shift in what is publicly stated and also what is told to staff. Public and nonprofit organizations typically publish their goals, and presumably they should be consistent with what the staff are working toward. More aspirational goals can also be added to the unfolding picture in a way that takes cognizance of the issues already captured and other goals. Ideally, the resultant goals system will provide a powerful message regarding the organization’s direction, and these goals will often be used as the basis for developing a mission or vision statement.

Fran’s Vignette Continued

Fran had managed to find a time for getting the senior management team together.

In tidying the new issue clusters that were emerging from a lot more statements, and considering the implicit goals, the team had begun to identify a goals system that would provide a focus for direction.

However, rather than getting a buy-in to the emergent goals system, there was resistance! She had thought that all of the senior leadership team saw the goals of the business school as she did. However, when they started laddering up to goals and reviewed the results, some members of the senior leadership team argued against a few of Fran’s proposed goals. They suggested some rewording to change the emphasis, and also suggested other goals. Moreover, they compared what Fran and they had captured with what had previously been presented to staff, on the basis of a previous strategy, and found a couple of anomalies. There were goals that were supposedly the focus of the school but in reality were not influencing practice in any noticeable way.

As they began to play with the goals structure, Fran also realized that there were a number of goals that were generic to all universities or business schools—for example, ensure high-quality learning—that did little to differentiate her school from others. The team began to focus their energies on considering what could be added that might provide differentiation and therefore potentially create a competitive advantage for the school (see Figure 3.22).

Figure 3.22. The Goals-Issues Hierarchy.

Fran also reminded them all of the goals of the university overall, since a new university-wide strategy had just been released. She wanted to make sure that there weren’t any instances in which the university’s direction and the direction of the school were diametrically or even slightly opposed. Thankfully, after reviewing the strategy document, they saw that the university’s strategy was sufficiently broad to allow the goals she and the team had developed to dovetail nicely with the wider organizational aspirations. This complementarity would allow the team to position the school so that it clearly contributed to helping fulfill the university’s aspirations.

Fran and her team now needed to test how the goals were supported by the issues, identify the key priorities, and ensure that the strategy was owned and understood by all. . . .

Identifying Central (Possible Priority) Issues

The map of issues will help in exploring emergent goals and also in developing a draft goals system. It will also give useful clues as to which issues are possible priorities. Most issue maps will contain a larger number of important issues than there is time, funding, personnel, or other needed resources to address effectively. Some means is therefore needed to determine where the most advantageous places are to focus attention and energy.

One way to establish priorities is to look at the structure of the map and identify which are the central issues—those that seem to be most knitted into other issues. Said differently, central issues therefore are those issues that have a high density of links around them. Central issues are usually good starting points for evaluating priorities. Although this characteristic seems to be focused solely on structure and not content, remember that the structure was derived from the content, and so an analysis of structure is also an analysis of content. Also bear in mind that in the process of tidying up the map, you are most likely to have finished with the most central issues in the center of the map in order to avoid unnecessary multiple crossed links.

Health Care Vignette Continued

The team had built and reviewed their goals map; they next needed to determine where to focus energy so as to achieve these goals.

The material was now in relatively neat causal clusters, which helped the team explore the structure of the map. However, they were a little surprised by some of the issues’ positions. Issues they had initially thought were really significant were now relatively peripheral, and some things they hadn’t even thought about had emerged as really central. For example, while they had recognized the importance of staff development, it had not really occurred to them how significant it was for staff to be able to work in a truly multidisciplinary manner and that this would influence considerably the better provision of training. They began to feel that they were getting a good handle on the situation and were beginning to identify a range of strategic actions that would help them in achieving their goals.

But there was still some exploration to do of the issue map—were there any other interesting properties of the map to take account of?

Identifying Feedback Loops

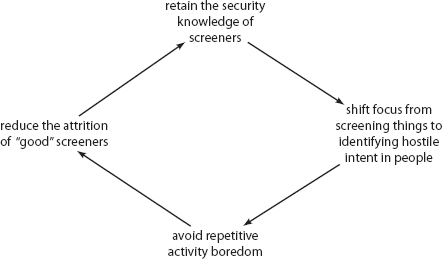

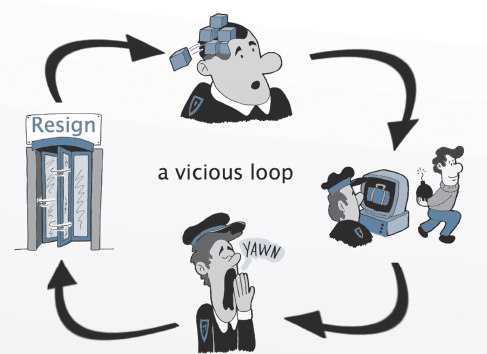

Seeing if there are any feedback loops is another important means of identifying priority issues. Feedback loops involve circular causality, which in a map shows up as a circle of arrows. The loop of arrows typically represents either a “vicious” or a “virtuous” circle. For example, the map could reflect that poor commitment of staff means more mistakes are being made, which causes demoralization of staff which in turn feeds poor commitment of staff—a vicious circle. Vicious and virtuous circles all have an even number of minus signs.

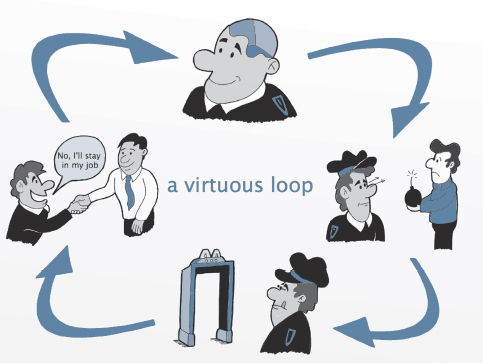

Sometimes feedback loops can be counterintuitive, so that without seeing them on a map nobody is aware of their effect on the future of the organization. Loops also can just be hard to see on a big map. When identified, however, loops are always worth exploring. This is because they reflect dynamic behavior. A strategy to stop a vicious circle is usually required; alternatively, a strategy to exploit a virtuous cycle may be needed.

Check first to ensure that all the links in a loop are correct. Check to see that all the links are causal, meaning they are means-end links rather than chronological ones. If the loop remains, then consider the nature of the feedback loop, since this can help in determining what action to take. For example, determine whether the loop is vicious or virtuous (see Figures 3.23a, 3.23b, and 3.23c). In these figures we show visually the behavior of both the vicious and virtuous cycles that can be created from the same feedback loop. Figure 3.23a shows the mapping logic of the feedback loop, and we have attempted to visualize this behavior in Figures 3.23b and 3.23c. In Figure 3.23b we show how this loop behaves as a vicious cycle in which, because of boredom from repetitive activity, good screening staff are resigning. This means the organization is losing the knowledge and experience of the screeners, which means inexperienced screeners are only able to do quite routine screening, rather than pay attention to people who may have a very hostile intent. Unfortunately, routine screening means boredom. Obviously there will be a limit to the continuous operation of the feedback loop, since at some point there will be no experienced screeners!

Figure 3.23a. The Feedback Loop as a Map.

Figure 3.23b. The Loop as a Vicious Cycle.

Figure 3.23b. The Loop as a Virtuous Cycle.

In Figure 3.23c we show this same feedback loop operating in a virtuous way in which the screener is experienced enough to spot hostile intent, which is not a boring activity, and therefore fewer screeners resign. This means that knowledge grows and there is a higher possibility of identifying hostile intent. Once again there will obviously be a limit to the cycles in which there is stability in the labor force and all screeners are experienced.

Vicious and virtuous circles can involve escalating behavior. This escalation can be in a virtuous manner of continuously improving the situation, or a vicious manner in which the organization is trapped in a downward spiral. Prior to declaring bankruptcy, the city of Detroit, Michigan, provided a good example of a vicious circle. The decline of the auto industry resulted in a lack of jobs, which negatively affected city tax resources, leading to tax increases. A lack of jobs and middle-class flight out of the city for a variety of reasons resulted in poorer residents, fewer taxpayers, less revenues, declining infrastructure and services, more crime, and a huge pension liability without resources to cover it. Declaring bankruptcy was one of the only ways of breaking out of the vicious circle, because it would allow a number of liabilities either to be written off or renegotiated.

Health Care Vignette Continued

The team had reviewed the issues and their impact on the goals and were seeking to gain further insights from their work.

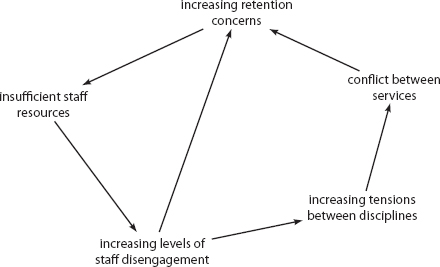

They had noticed that there was a worrying feedback loop that was a vicious circle in which over time the situation would get continuously worse. One of the issues that greatly concerned them was increasing levels of staff disengagement. This in turn was causing increasing tensions between disciplines and thus conflict between services. As a result there were increasing retention concerns exacerbating insufficient staff resources (see Figure 3.24). They urgently needed to do something about this vicious circle—particularly as the loop by its nature dragged in a lot of other issues that were influencing statements in the loop.

Figure 3.24. Example of a Double Feedback Loop from the Health Care Organization—in This Case a Vicious Circle.

As a result of this discussion, and further structural examinations, the team felt their strategy was coming together—now they had to make sure that everyone in the organization was familiar with it. . . .

Reaching Agreement on Goals and Prioritized Issues

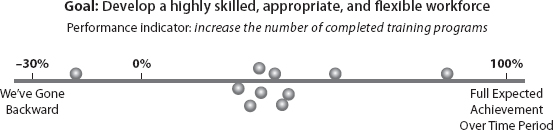

Once you have found and dealt with any ”orphans” (issues that are not yet connected to the main body of the material), explored goals (are they good or bad outcomes “in their own right”), identified central issues (those that are intricately interwoven throughout the map), and identified feedback loops (dynamic behavior), review those issues that have emerged as priorities. These are candidates for strategy development. In the anti-poverty alliance vignette, you saw in Figure 3.21 what the group agreed were its goals and prioritized issues. In the case of The Loft, see Figures 2.22, 2.23, and 2.24 for similar maps that provided them an overall sense of purpose and direction (for example, advance the artistic development of writers) and laid the basis for further development and refinement of strategies to achieve the goals and fulfill the mission.

Now It Is Your Turn for Some Practice!

Step Four: Translating the Map into a Strategy Statement

Following a careful analysis of the map, its structure, and its content, a strategy statement may now be prepared.

Reaching (Tentative) Agreement on Issues Areas for Strategy Development

At this stage, the map will include prioritized issues along with goals. The map thus provides much of the content basis for crafting a strategic plan. The map’s creators have been helped to surface, understand, structure, and analyze the statements and links out of which it was made—that is, the map’s content. Moreover, the process of creating the map greatly increases the likelihood that a resulting strategic plan will be implemented. Specifically, the creators have been helped to build and solidify the relationships, intersubjective understandings, and commitments needed to implement the plan.

That said, the map likely will not be easily understood by those who have not been involved in creating it. Moreover, many audiences for the strategic plan—senior leaders, boards of directors, funders, regulators, and so on—will be expecting a more traditional document. The process of creating the strategy document is therefore a key next step.

Reviewing the map is an important starting point. Take the time to (re)check the validity and thoroughness of the map’s statements and links around the priority issues for which strategies are to be developed.

As the review continues, paying particular attention to those issues that are structurally significant will help viewers develop a sense of possible strategic priorities. Each of the issues can be scrutinized and actions for their resolution identified. Possible actions may be found both by looking at the statements that already link in to a likely priority and by laddering down to develop other ideas.

Before determining which actions to take, however, make sure that all members of the group feel comfortable with the issues selected as potential priorities. Using the map’s structure to determine candidates does ensure that a rational and thoughtful process can be followed, but at times issues need to be added to the prioritized list for a host of organizational, social, economic, and political reasons. For example, an external stakeholder such as a key funding body might expect to see action taken in areas that interest them. Or government policies may dictate that certain actions be taken. When considering which issues should be priorities, consider internal stakeholders’ views as well. Ensuring that staff across the organization (or division, department, or subunit) feel ownership and commitment to the strategy is going to be a key part of ensuring its implementation. Having strategies that are politically feasible and practicable is important.

When choosing which issues to focus on for purposes of developing agreed-upon strategies, we strongly recommend that you always pay attention to relevant resource considerations. In our experience, the most an organization can realistically focus on at one time is between three and five strategies. An effective strategy is about determining where to focus energy; it is about priorities. It is not possible to do everything well. Pragmatically, it is very important to continuously consider who would be putting the actions into place, what resources in terms of both funds and staff would be needed, and what impact this use of resources might have on current operations. Articulating a strategy that is totally impractical can be more demotivating than not having a strategy.

When deciding on strategies and the actions to implement them, it is important to review each strategy alongside the other possible strategies. There are several reasons for doing so. The first is to make sure that an action designed to resolve one issue doesn’t negatively affect another. The second is to make sure any dilemmas are addressed effectively. The third is to explore whether an action chosen to resolve one issue could also help with addressing another issue, perhaps as a result of some adaptation. In other words, by making the action more “potent” it can help address more than one concern (see Figure 3.25). Finally, these checks will help ensure the overall coherency and robustness of the strategic plan by making you think about the organization and its strategic plan systemically, rather than partially.

Figure 3.25. A Potent Option Helps Address More Than One Issue or Achieve More Than One Goal.

Deciding on the Goals System

Next, examine the goals system. Converting this to text can be achieved by writing down the statement at the top of the system and then providing text that illustrates the goals supporting it. For example, the anti-poverty alliance’s goals system map shown earlier could be restated as follows:

To selectively influence decision makers to generate desirable policy changes, the alliance will seek to keep poverty on the public agenda, gain credibility with decision makers, and challenge policies and practices that keep people in poverty. Keeping poverty on the public agenda will be achieved through raising the public awareness of poverty, which in turn will be addressed by communicating the work we do and the ethos behind it and developing working alliances between organizations to tackle poverty.

The first draft might initially sound a little stilted, but should retain the precise structure of the map. Later word crafting can result in a better statement. This process helps ensure clarity about the goals and how they support each other. Make sure the goals statement fully reflects the causal arrows; otherwise, there is a danger of things being done for the wrong reasons. Be sure to review the goals statement against any value statements that exist within the organization to ensure congruence and, where possible, strengthen the connection.

This textual description of the goals may well provide valuable insight into what some people would call the mission of the organization. Many strategic management books devote extensive discussions to differences between mission, vision, and goals statements, and also to the differences between goals, objectives, critical success factors, and other terms. Remember that in this book we are more inclined to adhere to the language that fits the organization and with which the strategy-making group is comfortable, providing there is a shared understanding of the definitions.

Converting Issues into Strategy Statements

Once the goals system is clear, the next activity is to return to the prioritized issues and convert the wording into strategy statements. For example, if the key issue is “insufficiently trained staff,” then the strategy might be reworded “develop well trained multidisciplinary staff,” or alternatively, “stop our staff from being insufficiently trained.” Wording these strategies so that they both stretch the organization and yet are realistic is important, since otherwise the strategy as a whole may be received with some degree of disbelief and ridicule.

Next consider the promising strategies in light of the goals. A good place to start is to see whether the strategies do effectively support achieving the goals. The strategies’ efficacy may be increased if ways can be found to further develop or augment the strategies in such a way that they help achieve additional goals. Check as well to see whether there are any goals that are not being supported by strategies and any strategies that are not effectively supporting goals. In either case, it is worth spending time discussing the finding. If goals are not being supported by strategies, then either strategies will need to be developed or the goal should be revised or dropped. If there are strategies that do not support a goal, either a goal worth pursuing via the strategy must be created, or the strategy will need to be changed or dropped. In other words, every goal should be supported by at least one strategy in a powerful way, and every strategy should support at least one goal in a powerful way. Checking that every goal has strategies for achieving it and every strategy has a goal it helps achieve is an important test for the validity of the agreed-upon goals system and strategies. The structure of strategies linking to goals helps ensure strategic coherence and robustness.

As was the case with the goals system, when translating strategies into text there should be a clear articulation of the causal connections between each strategy and its associated goals. This ensures that staff members taking actions necessary to implement the strategies—and thus achieve the goals—are aware of the causal linkages between each step and can channel their energy appropriately and wisely. If the rationales for the actions are not made explicit, the chances increase dramatically that any actions taken will not help implement the strategy very well, may undermine the strategy, or may not address the strategy at all. A related reason for expressing causality is that doing so helps staff understand how their activities and energy support the strategy and the organization as a whole. When staff can connect their efforts to strategies and goals, they are more likely to think and feel they are making a worthwhile and meaningful contribution.