Networked Broadcasting

Game live streaming is an excellent example of the ways multiple cultural trajectories collide and iterate. It evokes structures and modalities associated with television, but it also fits within broader cultures of gaming and spectatorship, UGC, and telecommunications. It is an emerging form of networked broadcasting. It is entertainment that has typically routed around traditional media production and distribution outlets, tapped into gaming fandom, harnessed the evocative power of otherwise-mundane webcams, and piggybacked on—as well as created—net culture and computer-mediated communication. To some it may seem like game live streaming came out of left field. It is, however, tied to a longer historical trajectory of television and internet broadcasting, yet simultaneously deeply rooted in our contemporary moment, which is filled with online media services, maker/DIY movements, online life, and creative cultural production from all sectors of society.

Television: Artifact, Experience, and Transitions

Media scholar William Uricchio’s fascinating accounts of television help us understand how tied up game live streaming is with historical imaginations of what “TV” could be. As he notes, there has always been an “interpretive flexibility” to television, and one path early developers pursued related to liveness and interactivity. He shows, for example, that as early as 1883, French illustrator Albert Robida described a televisual apparatus that blended broadcasting with one-on-one communication, and could sit in both domestic and public spaces. This interest in facilitating “live extension, interaction, virtual presence, and communication” is woven throughout the history of television across a number of inventors and developers (Uricchio 2008, 291).1

Central to this particular project has been a focus on “technologies of simultaneity” that not only were in the service of communication but also national identity and state. Though the national project is not as resonant with game broadcasting, we can see how liveness works to bond people together, and create a shared set of experiences and identities around which they cohere. Whether it is in smaller streaming communities or large transnational audiences for esports, the liveness of game channels has proven a powerful, affective device. As I’ll discuss in later chapters, broadcasters regularly speak of the power of simultaneity in the productions.2 This ranged from the ability to engage in real time with the audience to harnessing liveness for sports broadcasts. The history that scholars like Uricchio present underscores how this approach has a long televisual history, and one that is tied up with deeper cultural and political formulations.

It’s also helpful to situate networked broadcasting by contextualizing it within transformations happening across traditional media more broadly and within television in particular. There are at least several threads within television studies that I’ve found especially fruitful to pull from to help illuminate game live streaming: television “after” TV, changes in production/distribution/consumption, the postnetwork era, and niche programming.3

As Uricchio (2004, 165) observes in the collection Television after TV, “From its start, television has been a transient and unstable medium, as much for the speed of its technological change as for the process of its cultural transformation, for its ephemeral present, for its mundane everydayness.” The tremendous shifts we’ve seen in just the last several years signal that we need always be attuned to this ongoing “transition” and the shortsightedness of conflating any particular historical instantiation of “TV” to “television” as a whole. This resonates with media studies scholar Sheila Murphy’s (2011, 5) point that television is as much a “cultural imagination” as anything, “more a set of connected ideas, beliefs, and technologies than it is any one thing that can be reduced to the home electronics device with a screen.” Shifting our understanding of television from both the network era model (think of the big three of ABC, NBC, and CBS) and material box in the living room toward broader transformations of the televisual across a variety of devices and protocols helps us situate game live streaming in a larger media context.

Seeing television as always in transition assists us in understanding some of the biggest shifts involving its intersection with digital technology along with alternative financing, production, and distribution models. The growth of the digital distribution of traditional content—such as Major League Baseball’s use of a streaming service and dedicated “app” that lives on everything from tablets to phones to game consoles, HBO’s popular Now service that bypasses cable subscriptions entirely, or Hulu’s streaming service for network television and more—all suggest the ways traditional media organizations have leveraged the internet. More pointedly, though, has been the rise of services like Netflix and Amazon that have distributed acclaimed series like House of Cards or Orange Is the New Black, which are solely available through online services. These shifts have captured both audience and critics attention. The rise of nontraditional paths to production and distribution have highlighted how serialized and televisual content can thrive on systems not linked to airwaves or bundled cable TV packages.

The growth of the net has caught the attention of both scholars and the industry who have tried to make sense of the changes taking place. Some have championed “second screen” experiences whereby television viewers augment their viewing with their cell phones, laptops, or tablets. Marketers’ enthusiasm for “engagement” metrics, often anchored around “social TV,” which is seen as the integration of simultaneous social media practices while viewing, has expanded what gets conceived as media use.4 And in much the same way scholars paid attention to how the introduction of the remote control reshaped home use, I suspect more will explore the ways computational technologies infused themselves into everyday audience experience.

Combined with the growing number of “cord cutters” or “cord nevers”—those viewers who forego traditional cable TV packages and make do with online resources (authorized or pirated)—we quickly get an image dramatically different from television’s classic “network era” in which we all gathered around a box in the living room to watch shows on fixed schedules via a limited selection of channels. Television scholars have argued it is a mistake to equate “television” with that simple image tied to a particular historical moment.5 Our current context is one in which traditional media organizations and the home TV sit alongside a myriad of devices we get content on as well as alternate production and distribution paths.

Televisual experiences are now significantly made up of a range of technologies we wouldn’t call a TV, via services that are distant cousins of ABC, NBC, and CBS, bypassing the airwaves or massive cable packages, and are increasingly tied to our online practices and lives. We still have watercooler conversations about traditional cable/television shows, but we might also talk to groups of friends (perhaps even just online) about videos originating from home recording studios.6 This is one of the most interesting aspects of our current media space: it interweaves traditional production and aesthetics with emerging genres and forms that are frequently created by fans, amateurs, or less mainstream media companies. Viewers consume content across this range. They may watch highly produced shows like HBO’s Westworld while also seeking out amateur YouTube videos or game streams on Twitch. Cycling across devices, from a large-screen home TV to an iPad or PS4, is not unusual. Live game streaming just becomes one more node in the mix.7

These trends are tied to powerful changes in media production and distribution. Television studies scholar Amanda Lotz notes the economic shifts in television production, especially practices that challenged labor structures through using “runaway productions,” which moved crews from union-based Hollywood to places like Canada that offered cost cutting measures. These shifts operated in tandem with new distribution channels—ones that also disrupted traditional revenue models. As she argues, “Changes in distribution shifted production economics enough to allow audiences that were too small or specific to be commercially viable for broadcast or cable to be able to support niche content through some of the new distribution methods, particularly those featuring transactional financial models” (Lotz 2014, 137). Attention to smaller audience segments certainly thrives on platforms like YouTube and Twitch, where viewers can track down content on both large games and quirky small titles that only a handful of people may avidly follow. The simultaneous growth of “reality television” and other content that does not require extensive writing, directing, and acting talent became a perfect breeding ground for the growth of UGC and low-cost game live streaming.8

This overall decline of major TV networks, rise in nontraditional production and distribution, and growth of niche outlets and programming characterize much of our current US television landscape. The emergence of game live streaming sits fairly easily within the historical trajectory of television writ large. Media studies scholar Lisa Parks (2004, 134) uses the term “post broadcasting” not to “refer to a revolutionary moment in the digital age but rather to explore how the historical practices associated with over-the-air, cable, and satellite television have been combined with computer technologies to reconfigure the meanings and practices of television.” Lotz (2014, 8) calls this the “post-network era” (beginning around the early 2000s)—a time when “changes in the competitive norms and operation of the industry become too pronounced for many of the old practices to be preserved; different industrial practices are becoming dominant and replacing those of the previous eras.” Game live streaming operates as a form of media production and distribution within these larger industrial transformations, and is a deep expression of them.

In addition to this shifting landscape of production, broadcast, and consumption, there is the long history of attempting to leverage interactivity in various ways. Children’s television and shows with various forms of game content have been particularly creative in trying to find ways to bring audiences in through interaction. Quirky systems like the Winky Dink (launched in 1953), which provided children crayons and a transparent sheet to overlay on the TV screen so they could directly draw on it as a means of interacting with special content, are probably some of the earliest experiments in trying to get viewers to work with programmed material. More contemporary shows like Blue’s Clues or Dora the Explorer formally structure themselves around a model of audience participation where they attempt to engage children in visceral, embodied ways by asking them to answer queries that the show’s characters make. Though audience participation doesn’t actually change the content, they are all examples of pushes to blur the boundary between program and viewer.

Other shows sought to encourage interaction such that audience input would actually change the content. The TV Powwww format (launched in 1978) had viewers use their telephones to call in and verbally issue a command (shouting “pow!” to fire on a target) that was then carried out in a real-time broadcast video game. The 1980s’ BBC show What’s Your Story utilized a phone-in choose-your-own-adventure model that allowed the audience to shape how the narrative unfolded. The 1980s’ Canadian production Captain Power, picking up on the same technique as Winky Dink in merging content and equipment, offered a special toy for engagement. Children who had purchased the “Powerjet XT-7 Phoenix” (a light gun akin to the NES Zapper) were able to “fire” at the TV and carry out live battles. As the system warned, “The TV show will fire back. It will fire back. Score, or be hit. Do you understand?” (Toal 2012). Finally, shows such as Big Brother or competitions like Eurovision that rely on direct viewer engagement through voting systems also point to ways producers have sought to draw audiences into how content actually unfolds.

I leverage these threads of scholarship and examples when I use the term networked broadcast. Game live streaming—rooted in globally distributed user-content creators utilizing third-party platforms, involving social interaction as a core component of the broadcast, and embedded as well as amplified across a variety of sites—exemplifies the notion of a network. Game live streaming is, as I will show throughout this book, an assemblage of actors, technologies, and practices. It is a form that plays with the boundary lines between audience and producer. Content is co-constructed through the network and via the transformative work of play. This network of connections and content, all within a broadcast frame, articulates where game live streaming sits. Media studies scholar John Caldwell (2004, 45) argues that understanding the current moment in which digital technologies intersect television requires paying “as much attention to the communities and cultures of production” as to “either political economy or ideologically driven screen form.”

Thinking of game live streaming as a new form of networked broadcast also speaks to a long-standing concern among some scholars who have seen TV as an overly individualized, personalized, and privatized microspace of viewership. While these tendencies are possible, and may even come to eventually dominate game live streaming, at its infancy they are not the core orientation. Game live streamers are deeply embedded in social networks and communities of practice. The platform has been rooted in communication between broadcaster and audience members, or audience members with each other. And though viewers can surf across a variety of niche channels in this space, they do so within a larger platform milieu—one that sees itself as both a “Twitch family” and a host to numerous smaller subcommunities. The network—figured in production, distribution, and consumption—is a central metaphor and actual anchor for game live streaming. Combined with the transformative properties of play, it is a vibrant space of new media development that builds on the history of television.

Internet Broadcasting

I would be remiss if I only looked at game live streaming through the lens of television or transformations in that space. In Murphy’s (2011, 88) book How Television Invented New Media, she prompts us to ask, “How is new media not just television all over again?” She wants to make sure we don’t overlook the televisual in the lineage of “new media,” and it is certainly the case that live streamers have their eye on TV conventions and pull from them at times. Her historical look at television’s influence on gaming (and new media broadly) anticipates what we see in game live streaming, and her book is incredibly valuable in situating a range of digital media within a longer television history.9

While she is working her analysis from the direction of understanding how television provided a foundation for what we often black box as new media, I find the question generative in the reverse direction as well, primarily analyzing with an eye toward internet and game culture. Though the internet is increasingly used to distribute traditional media content, Murphy’s question can be productively turned to allow us to weave in early net histories around cam culture, UGC on sites like YouTube, and the rich legacy of multiplayer gaming and spectatorship to understand the growth of internet broadcasting. Game live streaming, while resonating with television and the televisual, also has a lineage that is a motley mix of several other domains rooted in specific technologies and cultures of the internet.10

CAM CULTURE

As someone who used old modem-based bulletin board systems and watched the variety of enthusiastic experiments that bubbled up on the net in the 1990s, I immediately thought of early internet cam culture when I first saw live streaming. The dream of videophones and telecommunication where you can talk and see people has long held sway in the popular imagination. What was striking in the mid-1990s is how viable it became for everyday users. We perhaps take this for granted now given programs like Skype or the small cameras that come preinstalled on everything from laptops to tablets to phones, but only a couple decades ago people were starting to play with live video feeds.

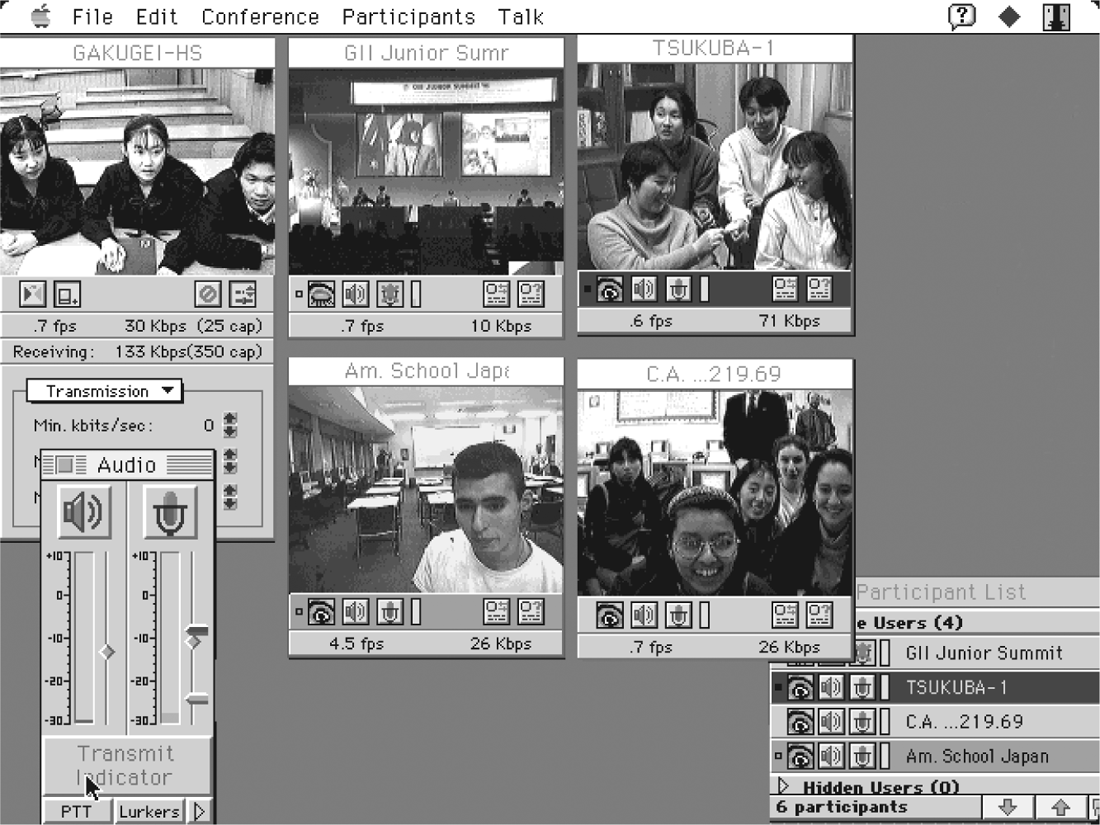

Using low-resolution black-and-white cameras, people began to connect with each other in real time over the internet, most notably through a free program developed in 1992 called CU-SeeMe (see figure 2.1).11 While early initiatives were often based in education or science (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration being a notable early adopter), many of the connections that were getting made were simply opportunities to meet people and socialize.

FIGURE 2.1. Global Schoolhouse classrooms collaborating via CU-SeeMe. Photo by Yvonne Marie Andres, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Some, including myself, used programs like CU-SeeMe to augment their social connections in a variety of online spaces (see figure 2.2). For those who spent time solely with text, the camera offered an exciting new arena of play. As the early instruction book Internet TV with CU-SeeMe put it, “Computer-based videoconferencing is startling. It redefines your relationship with your computer and, more importantly, how you communicate electronically with other people around the world” (Sattler 1995, 2). Even in these early moments of using web cameras to connect with others online, people were sensing the power they had to shift otherwise-instrumental encounters to more relational ones. Using the technology to talk to each other and connect, frequently across distances, became a central part of these early explorations.

FIGURE 2.2. Multiwindow internet session from 1998 showing the author with friends simultaneously together in a text-based virtual world in the background and CU-SeeMe in the foreground.

Internet users experimented with how to visually connect to one another and create shared spaces mediated through cameras. Media studies scholar Ken Hillis (2009, 9), in his rich study of online life, conveys the immense affective power of webcam usage, writing that “at times these encounters induce feelings of absence and ‘wish you were here,’ yet mostly they have the opposite effect: everyone feels that they are somewhat in each other’s presence.” This sense of presence at a distance, that you are somehow together with others via video, is a powerful hook in our shared network experiences. As cameras became less expensive and broadband access more widespread, technologies evolved that allowed inexpensive forms of telepresence.

The late 1990s and early 2000s were a tremendous moment of exploration for those looking to develop broader broadcasting possibilities, in particular though continual live streams of their everyday lives. Sometimes these involved sexual activity, but often they were simply mundane feeds allowing viewers to peek in and, notably, chat with the broadcaster.12 One of the earliest examinations of this phenomena was internet researcher Theresa Senft’s (2008) chronicling of the rise of the 1990s’ “cam girls”: women who would live broadcast often out of their house 24-7 to viewers who stopped by their website.13 Though all too often these early net forays were written off as simply exhibitionism, Senft presents a much more nuanced analysis of the ways that “immediacy and intimacy” were created in these spaces between broadcasters and audience. Both Hillis and Senft highlight these links, the flow of conversations, getting to know and be known (even if within a frame of performance), and the disruption of an easy story of voyeurism. Understanding viewers as connected to the broadcaster (sometimes invoked through the metaphor of “family”), the emphasis on being “responsive,” and the affective nature of cam work is key to this early moment of interest broadcasting, and harkens to similar moves we see within game live streaming.14

Senft’s insight into not only the culture and aesthetics of camming but also the material and economic aspects provides a useful foundation for thinking about what we see on platforms like Twitch. Her notion of microcelebrity—described as “a new style of online performance that involves people ‘amping up’ their popularity over the Web using technologies like video, blogs and social networking sites” (Senft 2008, 25)—plays a powerful role among professional live streamers. Though she argues that both traditional and new forms of celebrity require one must “brand or die,” Senft distinguishes microcelebrity as dependent on “connection to one’s audience, rather than an enforced separation from them” (26). Fame on these platforms is one tied up with the affective and relational work broadcasters undertake.15

From these earliest moments of experimentation, the interaction between the person on camera and the watching audience was central. As the documentary We Live in Public (2009) recounts in its telling of some of the earliest experiments with online streaming, the audience being able to “chime in” has always been central to internet broadcasting. The film notes that whether it was in the broadcasts of early internet shows on the groundbreaking 1998 Pseudo.com network, which mirrored traditional television in having scheduled shows around various topics, or its founder and early cam adoptee Josh Harris’s wired-up house that broadcast 24-7, a sidebar text window hosting the audience chatting away in real time was always part of the way these ventures mixed the televisual and internet culture.16

Though these early forms of cam broadcast certainly fit neatly within a story of the rise of reality TV, the distribution paths and synchronous communication between audience members with the broadcaster and each other are distinctive to the internet. Early cam culture highlights how average internet users in the 1990s were taking up various technologies, and mobilizing them to their own social and interactive ends. The power of televisually connecting in real time with others, navigating a space of communication and performance simultaneously, and revealing otherwise-mundane but evocative daily life to others are lines that connect these older video experiments to current game live streaming.

UGC, YOUTUBE, AND LABOR

While camming as interactive social space remained fairly niche in the 1990s, a second thread of internet culture played a notable role in the growth of live streaming: the rise of UGC.17 The creative works of people well outside traditional industry production has been central to new media development in the last several decades. Players making “mods” (modifications) to alter their games or create content for them, fans producing videos or stories to augment or celebrate media properties, artists producing mash-ups, or extensive databases and catalogs created by users to facilitate the activities of others are all examples of UGC, and have become a strong component of internet culture. Audiences have been active in taking up this content.

Over the last decade, the creative activity of everyday users on YouTube and other sites has been tracked by a number of scholars, detailing a circuit that flows from user-producers to other audience members across a corporate platform.18 For example, YouTube’s 2017 statistics note it had “over a billion users—almost a third of all people on the Internet—and every day, people watch hundreds of millions of hours of YouTube videos and generate billions of views.” Although traditional creative industries such as music or film production companies now supply significant content to the platform, its roots and the bulk of its material have historically come from users. Videos on the site range from independent musicians distributing their songs to silly pranks and stunts. Gaming-focused videos have grown in popularity. As it has come to be identified as a site of value, YouTube has also been monetized and regulated.

The site regularly serves as an exemplar of what is termed “participatory culture.” Media scholar Henry Jenkins (2006a) describes our current moment as one in which fans are active producers and consumers of all kinds of material generated not by major media entities but instead by each other. Rather than simply passively consuming content produced by large companies, a notion of participatory culture is meant to evoke a sense that average people are generating all sorts of stuff and engaging meaningfully with it—and each other.19 Digital media researcher Axel Bruns (2006, 2) has proposed the term “produsers” to describe those who undertake “the collaborative and continuous building and extending of existing content in pursuit of further improvement.” This collaboration can take place not only between fans and commercial content but within communities too. Sometimes that content is wholly new, while at other times it remixes and repurposes existing properties, from books to songs to movies to games. Ultimately this perspective on cultural production is one that focuses on the mix of top-down and bottom-up creative practices across not only corporations but also individuals and communities—ones often rooted in fandom.

Internet and media scholars Jean Burgess and Joshua Green (2009, 25) leverage the concept of “vernacular creativity”: “the wide range of everyday creative practices (from scrapbooking to family photography to the storytelling that forms part of casual chat) practiced outside the cultural value systems of either high culture or commercial creative practice”—to understand what we see, for example, on YouTube.20 One of the strengths of Burgess and Green’s approach to understanding the circuits of production and consumption is their emphasis on seeing not only the creation of videos but also the sharing and discussion of them as a form of social networking. This approach is incredibly important for analyzing game live streaming, and as I will discuss throughout the book, the networking and relational aspects are central for understanding not only the creators on the platform but those who are in the audience too.

They also resist any move to claim such activity as “either trivial or quaintly authentic,” and instead want us to see how it “occupies central stage in discussions of the media industries and their future in the context of digital culture” (ibid., 13). Their focus on “consumer-citizens” is, as we’ll see, particularly resonant for understanding game live streaming. While they rightfully argue that that simplistic dichotomies between professional and amateur, or commercial or noncommercial, is not analytically helpful, we can reflect on how the labor on these platforms is situated within contemporary capitalism. The platforms on which UGC frequently live are typically commercial entities in and of themselves, or are supported by advertising and thus tie them to such systems.

Going back to theorist Tizania Terranova’s (2000, 34) foundational piece in which she asked us to consider the ways that the “cultural and technical work” of the internet is “a pervasive feature of the postindustrial economy” is a useful continued provocation for looking at platforms like YouTube and Twitch. Terranova, in tackling a framework for understanding a digital economy, asserted that we should not avoid thinking of labor, even if it doesn’t look like the typical wage labor we are used to. Instead, she asks us to consider immaterial, often-free labor as central to how new media works. As she puts it, “Free labor is the moment where this knowledgeable consumption of culture is translated into productive activities that are pleasurably embraced and at the same time often shamelessly exploited” (ibid., 37). This approach helps us recognize the range of contributions made to platforms—from the production of YouTube videos to status updates on our favorite social media—as a form of labor that often taps into powerful affective, even relational modes. While the question of exploitation is one both theorists and users themselves wrestle with, at a foundational level this immaterial labor that unpins so much of our current digital life is a crucial part of understanding live streaming.

In many ways, this book extends the conversation about labor and the digital economy by situating the activities of the live streamers I chronicle here as undertaking new forms of media industry work. Production and distribution are salient categories that broadcasters themselves take up and articulate. For variety streamers, vernacular creativity sits alongside of and gets worked through traditional industry logics, while simultaneously pushing back on and at times transforming them. And for esports companies, live streaming is deeply located within unfolding shifts in sports/media industries. Game live streaming continues a conversation about labor in the digital economy, but also extends it by situating it within a media industry frame tied up with varying forms of practice and compensation.

Indeed this double side of YouTube has, for gamers, long been the norm as it became an important venue for remix and original work as well as amateur and commercialized activity. The platform offered gamers some of their first opportunities to not only engage in creative labor but also attempt to monetize it. “Machinima”—video productions that use game engines to create their content—found an ideal home on the platform so much so that it inspired the creation of the multichannel network (MCN) structure: a collection of many individual broadcasters banded together as a collective. Commentaries, tutorials, and general game entertainment shows have also taken off over the last several years. Due to the possibilities for compensation through the platform’s advertising system, some content creators have been able to make a living from their UGC. Launched in 2007 as the YouTube Partner Program, approved content providers get a cut of the revenue from the commercials that run on their channels alongside their own original productions. Though in April 2017 the monetization model shifted the threshold for partners to start making money (at the time of this writing, you must now have ten thousand lifetime views on your channel), the program was groundbreaking for the way it sought to wed UGC and commercialization.

In her study of one group of content producers, the Yogscast, game studies researcher Esther MacCallum-Stewart provides insight into the rise of an expert team of media producers via their deep fandom. She traces the growth of podcasts and webcasts (typically recorded videos) within gaming, and shows how these casters “are not only spokespeople for the gaming community at large but they are also a powerful force in both spreading information and advertising various aspects of games and gaming” (MacCallum-Stewart 2014, 83). Tracing their economic success, she notes that their work is not limited to simply information dissemination. MacCallum-Stewart considers their own status as celebrities, and leveraging the work of authors like Matt Hills (2002), positions these broadcasters as “big name fans”—a group that has gained notoriety, yet at its core retains a fannish identity and is deeply dependent on other gamer fans for its success. This border identity and the extensive work these content producers do (including community engagement) are similar in many ways to the live streamers in this book. Although the broadcasters I have studied produce a slightly different kind of content and raise unique issues with their live interactions with their audiences, the themes around fandom and communities are resonant with those MacCallum-Stewart identifies.

As she describes in her case study of the Yogscast, what began as fan activity grew into a business. Game studies scholar Hector Postigo (2016) has done important research investigating forms of gamer productions that are monetized, including “converting play into YouTube money.” Of particular value in Postigo’s work is his look at how the technology of YouTube is a critical component of the UGC system. Focusing on the affordances of the platform, he explores how everything from the uploading system to the ability for viewers to comment and rate work transforms “making gameplay” into “making game pay.” His analysis is particularly helpful in both revealing the nature of this form of UCG and pushing against simple dichotomies of exploitation/freedom or work/play when trying to understand YouTuber’s content production. As he argues, “Under these conditions, one should not conceptualize play and production as distinct. Rather, the creative and the productive processes are melded in the context of making gameplay, and play and production are unified processes” (9). In many ways, this is indeed the dream that YouTube sought to make real in its formulation of how the system would work, and Postigo insightfully reveals not only the labor of these gamers but also how the platform facilitates the commercialization of their creative output.

As live streaming has developed, more users from YouTube have begun to broadcast on sites like Twitch, and at the same time, content has cycled out from the live streaming space back onto YouTube as a host for VOD shows. Many of the themes around content production along with the relations between games, producers, and the fans of each can be seen first arising on YouTube. Some of the earliest experiments with UGC monetization and the development of sustainable economic models for producers began there. It, and the integration of UGC into gaming broadly, is a key node in tracing out a history of game live streaming.

Multiplayer Gaming and Spectatorship

Into this mix of inexpensive video telecommunications and the rise of UGC, we must now fold in the long robust history of multiplayer gaming and pleasures of spectatorship. From the earliest days of digital gaming, people gathered together to share their play, cooperate, and compete. Arcades were an important site of multiplayer gaming, and fostered not only competition but also spectating one another’s play as you waited your turn or admired a skilled player at the controls.21

As home consoles rose in popularity (and arcades faded), people found themselves seated next to each other on floors and sofas playing together, often still having to hand off controllers. Game consoles brought digital play into the home, and as such, it became a part of domestic leisure practices and contexts. Sharing devices, controllers, and cartridges with families and friends alike extended the notion of multiplayer gaming beyond the constraints of the game itself to the social milieu in which play is located.

The growth of the personal computer as a device for play also fostered multiplayer experiences. In the beginning, this mostly ranged from once again taking turns at a machine to sharing games on disks. Eventually hooking machines up together into local area networks (LANs) and jumping into shared digital space to game together in real time became a significant development (especially around competitive gaming and early esports).

With the rise of the internet, the ability to play with those not in your immediate geographic area grew. No longer needing to be physically present together (bodies or machines), networked gaming online quickly took off starting in the mid-1990s. Massively multiplayer online games, team-based first-person shooters, or one-on-one strategy games all came to be hugely popular. With the growth of mobile gaming, one more node was added to the story in which the everyday experience of digital play is now deeply, even mundanely situated in a multiplayer context often mediated through a network.

Woven throughout all these variations on multiplayer gaming is the experience of spectating play. Whether waiting for a turn at an arcade machine, having a console controller passed over, or watching a heated online battle continue after your character has “died,” spectating has been a part of gaming since the beginning. Even with single-player titles, watching another person move through the game can be compelling and entertaining. At times spectators even share labor with the primary player, as in the case of offering tips or helping map out the game space. Game scholar James Newman (2002, 409) has described these forms of engagement as having a notable role in play, arguing that though the spectator may not have their hands on the controller, “they nonetheless demonstrate a level of interest and experiential engagement with the game that, while mediated through the primary player, exceeds that of the bystander or observer.” Spectating has its own set of pleasures and forms of affective experience. It can itself be a form of ludic engagement and has long played an important role in gaming.

It is into this mix of television transformations, internet culture, and multiplayer experiences that game live streaming arises. These are long interweaving trajectories across both traditional and new media. Game live streaming points to the ways that the televisual is worked over by internet and game culture. It can also be a tremendous “canary in the coal mine” for our broader critical considerations. It can give us a glimpse of cutting-edge media activities and cultural shifts. Live streaming intersects with conversations happening in internet culture around user-created content, monetization, and forms of governance. It dovetails with broader analyses of media, especially around alternate production and distribution mechanisms. At the same moment that services like Netflix or Amazon are shaking up traditional television production, distribution, and consumption, game live streaming is at the critical juncture of a new broadcast landscape. Gamers are creating media products for other players. They are doing so not via traditional television but rather through online sites and with techniques resonant with online life and gaming. Tracing out the growth of live streaming from its early roots that intersect the televisual, internet culture, UGC, and gaming, we find a domain that offers insight into the entwining of our network and media lives. It reveals an era of networked broadcast.

The Networked Audience

The notion of the network will figure into the story that follows in a variety of ways: via the assemblage of technologies and actors that make live streaming possible, through the use of the internet for distribution and participation, the construction of a media experience across multiple platforms and sites, and the complex connections and interrelations between broadcasters and audiences. Before diving more deeply into the cases of variety and esports streaming that is the focus of this book, it’s worth saying a few words about live streaming viewers—the networked audience.

Media scholar Alice Marwick (2013, 213) also uses this term in her work on celebrity and social media to highlight the connected nature of the viewers, especially around the practices of “lifestreaming.” As we’ve seen, live streaming is situated in a much longer history of television, the internet, UGC, and games. While it has resonance with other forms of media engagement, from traditional broadcast to recorded gameplay through videos on YouTube, the forms of engagement and work these online audiences undertake should be understood in their own specificity. Though I will discuss them in more detail as I concentrate on specific cases in the remainder of the book, a few broader strokes are worth laying down to help situate audiences.

WHY WE WATCH

While my fieldwork has not focused on audience members, over years of work in this domain I’ve come to have a better sense of why people tune into game live streaming. Simply put, there is no single reason. David Morley (1992, 139) noted that “‘watching television’ cannot be assumed to be a one-dimensional activity of equivalent meaning or significance at all times for all who perform it,” and it is much the same for game live streams. Watching them happens in a variety of contexts, and depending on the game, viewers, broadcasters, and fellow audience members can tap into different pleasures.

There are six clear motivations for why people watch game live streams: aspirational, educational, inspirational, entertainment, community, and ambience.22 These may wax and wane in any given viewing session, they are not singular, an audience member may approach different broadcasts for different reasons, and they are not determined by the content of the broadcast itself but instead tied to the context and disposition of the viewer. These six are a snapshot of what viewership currently looks like, and I anticipate audience motivations will shift and develop as the medium does.

Aspirational: The aspirational mode is an orientation centered on wanting to be a better gamer, although it can be diffuse in its focus and is often an early entry point for many viewers when they find out about game videos. A viewer may aspire to be more skilled, hold greater game expertise, or display virtuosity. They may also aspire to be a popular, beloved public figure like their favorite streamer. While the aspirational at times weaves in with the educational or inspirational modes I will discuss next, it frequently operates at a more affective level as a motivating feeling as well as embodied sense of desire and hope.

Educational: Aspirational forms often become educational motivations. One thread that connects some live streams to recorded game video on YouTube is the learning opportunity. This mode involves an audience member using the broadcast to investigate something about the game—perhaps to help decide if they want to buy it or gain insight into specific techniques for how to play. Within the educational frame, broadcasters may provide everything from how-tos to nuanced critique about a game based on knowledge related to a genre, for example. Viewers may also glean subtler tips and tricks from watching someone play, even if that is not the intended orientation of the broadcaster. Like the aspirational orientation, this mode is often a gateway to game videos, and live streaming in particular.

Inspirational: Another major driver in viewing is tied to fandom. People may find themselves looking up information on their favorite game, series, or even genre, and discover a pleasure in watching another person playing something they are passionate about. This mode tends to spur or trigger deep engagement in the viewer as they connect their own experience with that of the broadcaster’s. It may tap into an aesthetic experience too, of simply appreciating the play they are watching. The audience member may feel things viscerally, prompting a remembrance of their own play. Usually it even inspires them to go play or replay the game being watched. For some it also spurs a desire to stream the game they are fans of, moving them from spectator to producer.

Entertainment: One of the most powerful motivators for watching live streams is the pleasure of being entertained. Often this is through humor and the performance on-screen by a sharp-witted fellow gamer. It can also be through the experience of discovery alongside the streamer, where you as the viewer “travel along” with them as they play the game or experience the emotionality of the game through their play. In live streaming, adept broadcasters are good at drawing the audience into the experience as well. They will ask questions, offer advice, and not only play the game but also “play to” the camera for the audience’s benefit. The entertainment frame can be reminiscent of sitting alongside a friend on the sofa while they are playing or it can tap into the feeling of watching an accomplished performer, as on television.

Community: Woven throughout many of these other motivations can be a desire to have a feeling of community or a social experience. For many, live streaming becomes a place in which their fandom for a game is embodied in the caster, and as a member of an audience, is transformed into a collective experience. Viewers may enjoy connecting to other audience members through the live chat, which sits off to the side of the broadcaster’s stream. There they can talk with other viewers or the broadcaster about the game or their lives, or make idle chitchat. It is common to hear longtime viewers remark on how they originally started watching primarily for the streamer yet ultimately became a part of the larger community on the channel. As I will discuss more in later chapters, broadcasters often work hard to foster this sense of social engagement and connection, and it can form a powerful tie between viewer and channel. On larger esports channels, the community motivation can morph into the pleasures of participating in a large anonymous collective. Much like sitting in a sports stadium and hearing the cheers of the rest of the crowd or participating in a “wave,” joining in a live stream can anchor an individual to a broader group experience.

Ambience: A final category is one longtime viewers often know well, but that can surprise those who aren’t familiar with live streaming. Time and again I’ve spoken to people who keep streams on all day as a kind of comforting background noise and movement. In these moments, play becomes transformed from discrete instrumental action or entertainment to a more mundane yet still-engaging quality of everyday life. I think of this as ambient sociality, where the broadcast becomes a fixture in one’s space. The presence—of the game moving in the background, the broadcaster’s image or voice, or even the audience visualized by the chat window—taps into a desire to be connected to something outside one’s immediate surroundings at a deep sensory level. Much like people have done with television or music over the years, live streams can become a background ambience to everyday life.23

While the remainder of this book will focus on those on or behind the camera, it is important to get at least this small glimpse into the draw of watching live streams. The pleasures of being an online audience member are multiple, overlapping, and can vary even within a single viewer. They evolve and morph over time in tandem with the development of the medium along with the viewer’s own experiences and contexts. Sometimes, as with ambient sociality, they are akin to what we have experienced in traditional television, while at other times, as in the educational mode, they speak to something distinctive in gaming. Overall, they reveal that the audience side of the equation is just as complex and nuanced as the production side, and well worth continued attention, especially by media scholars who might investigate this new form of cultural participation.

TALKING BACK

As I note above, connections with the broadcaster and other viewers can be a powerful draw to game live streaming. One of the most distinctive features of the form at this point is how central an online synchronous chat window for the audience to participate has become. On Twitch, text conversation occurs in a window off to the right side of the screen.24 While originally built on IRC, it has now evolved into a specialized hybrid, though it continues to integrate with chat bots (small pieces of software that monitor the conversation, and do various forms of moderation or info sharing) and still lets you issue traditional IRC commands like “/me action.” The chat window is also a key place where broadcasters can keep tabs on who is coming and going from their channel, see what their audience is saying, and catch questions that they then generally answer audibly via a microphone.

Chat is where you see mass crowd behavior too, for both good and ill. Researcher Drew Harry, who received his PhD from MIT’s Media Lab and went on to lead the science team at Twitch, did fascinating work exploring potential systems for live streamed crowd experience (2012). He was the first person to explain to me how a fast-scrolling chat window, filled with text that wasn’t conversational but full of excited exclamations, repetitive emoticons, and memes, could be seen as akin to the cheering one would find in a sports stadium. This form of communication, dubbed “crowdspeak” by Colin Ford and colleagues (2017, 859), while appearing on the surface as “chaotic, meaningless, or cryptic,” actually has “‘practices of coherence’ that make massive chats legible, meaningful, and compelling to participants.” Though there remains much to be done to better facilitate communication in live streaming spaces, many viewers have eagerly taken up the chat component of broadcasts.25

From my first interviews with Twitch developers and executives as well as streamers themselves, I was told over and over how central chat is to Twitch. The platform’s annual year in review stats typically includes the number of chat messages that flow through the system. In 2016, for example, there were 14.2 billion chat message sent (Frietas 2016). While YouTube content creators and their audiences use the comments field on a video’s page to communicate asynchronously, what happens in Twitch chat is something quite different. It is a space of real-time dynamic exchange not just between broadcaster and audience but the audience members with each other too. Chat can also include references to things having nothing to do with gaming or Twitch that weave their way into an otherwise-specialized subculture. This component of live streams taps into language around “engagement” that social media marketers often use superficially.26 It is part of a longer trajectory of interaction that spectators, fans, and audiences have always had with media objects. Contrary to the rhetoric of the passive viewer, many studies have shown over the years the creative, active ways audiences take up content. Live streaming chat continues this thread, and as users frequently do, iterates it.

While conversation and symbolic communication (in the form of emoticons and memes) makes up the majority of Twitch chat, it has also been used for gameplay. Twitch Plays Pokémon (TPP) was the first breakthrough that took the chat functionality of the site and, letting users actually input game commands via it, facilitated collective play (see figure 2.3). As you can probably imagine, thousands of people simultaneously inputting actions led to often-humorous, sometimes-frustrating repetitions like endlessly attempting to use an unusable item or accidentally “releasing” Pokémon monsters into the wild. Player-spectators engaged in lively, if at times comic, debates about whether to use a voting system to tally inputs, thus trying to act cooperatively to make intentional game choices (dubbed “democracy”) or surrender to the serendipities of chaos that emerge when thousands of people try to play a game at once—known in the TPP community as “anarchy.” Players took up these positions with humor and frequently real intensity of purpose; your approach became a kind of playful philosophical declaration that itself was battled out via a metacommand system. The chat window evolved to accommodate a flood of commands while retaining discussion (via a commands/text toggle to help people follow it all).

FIGURE 2.3. Twitch Plays Pokémon screenshot, 2014.

TPP also produced an entire subset of fan engagement including stories and complicated mythologies, T-shirts, and memes, and eventually even leaked out into a broader popular culture (see figure 2.4).

FIGURE 2.4. “First date.” xkcd comic by Randall Munroe, Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 2.5 License. https://xkcd.com/1333/.

Indeed, the first time my friends and colleagues started to talk to me about live streaming was as a result of hearing about TPP in major news publications. The idea of utilizing chat for gameplay purposes, and harnessing the engagement of the audience, is now a genre in and of itself that has been used for a variety of games on the platform.

AUDIENCE WORK

There is something generative about the way that TPP pushes a reflection on the nature of audiences to the fore. The very idea of “watching” can conjure up an image of a passive, individualized, even isolated spectator. Yet this is something contemporary media studies has long problematized, well before we began collectively inputting game commands as we watched live streams. Media scholars Sut Jhally and Bill Livant (1986, 125), situating audiences within a media economy, argue that understanding “watching as work” addresses the concrete “value creating process” that audiences are engaged in as well as helps us think more broadly about viewership. Though their account is primarily focused on a critical materialist conceptualization of audiences, it does speak to the low-level affective ways audiences are always entangled in value production within the media industries. A model of viewing where people are always engaging with content, decoding what they watch, and making meaning of it within their specific contexts has been fundamental to contemporary media theories for decades now (Hall 1980). This engagement is deeply situated in personal and social conditions; understanding it as such disrupts the rhetoric that viewers are simply isolated passive receivers of a given media message. Whether it is via material arrangements and domestic conditions or identities and culture, we are always working with the media in our lives refracted through our specific contexts.

As I discussed earlier, theories of participatory culture have been central to understanding contemporary media and internet life. An important part of that intervention was highlighting the “once invisible work of media spectatorship” (Jenkins 2006b, 135). Though some examples in this domain focus on concrete transformations and interventions that audiences make to media they engage with (from remixing and republishing content to facilitating bottom-up funding campaigns), the approach illustrates the fundamental status of audiences as active. Theories of participatory culture build on a much longer history within cultural studies that understands the active engagements we all make with culture, even when commercialized.

This mode sets up for us a richer understanding of viewership reflected in the diversity of motivations, contexts, and uses of spectating live streams. From learning to be a better competitor to talking to people on a channel, live streaming audiences are regularly engaged and often social. Streaming communities will also frequently expand the sphere of interaction with other platforms or creative activities, such as forming groups in games or producing fan art. While some audience members may use a broadcast for a kind of ambient presence, this too can speak to an intentional form of engagement. Even lurking, quietly taking inspiration, or simply following a favorite broadcaster by clicking on a button all point to ways in which audiences actively navigate, experience, and are working with content.

These practices embody broader media trends where audiences are not simply consuming content but are also part of a circuit of production through their engagement. Aside from ways they are enlisted into productions by their very presence (something I explore more in later chapters), their own gaming becomes linked up with the experiences of spectatorship. Viewing others playing games can animate a desire to play, or play in particular ways (for instance, adopting the techniques and strategies of pro gamers). It can be an affective experience, pulling you in and kindling a ludic stance. It can be visceral and embodied; you can find yourself leaning forward, at attention.

Amid understanding spectatorship in these ways, we need to keep an eye on how the laboring audience is constructed and deployed within broader industrial shifts. That turn is crucial to not painting an overly celebratory or liberatory narrative about the active audience. Media scholar Jonathan Sterne (2012) wisely cautions about how “interactivity” and attention is leveraged into “market value,” arguing, “When people’s participation becomes someone else’s business—and here I mean business in the market-share and moneymaking sense of the term—the social goods that are supposed to come with it can be compromised.” Internet scholar Kyle Jarrett (2008b) likewise prompts us to critically reflect on the ways that interactivity becomes bound up with a notion of the neoliberal subject via systems that push us to always produce, always consume.

It is certainly the case that game live streaming is built on the commodification of a range of labor, and its audience work neatly dovetails with how the media industries have been realigning their production and economic models to deal with the internet. Enlisting participation for the purposes of monetization is in the DNA of not only Facebook and Twitter but Twitch as well. Traditional media has long chased after a dream of interactive audiences—valuable ones that can be captured and sold to advertisers—and the growth of new metrics and participatory fan communities online has been tantalizing to those in the business of selling audiences.27 A significant part of the rhetorical framework around Twitch is, indeed, a focus on the breadth and measurability of its engagement—a particularly enticing rubric for advertisers.

Game studies scholar Nick Taylor’s research on esports and the process of “audiencing” brings this conversation directly into the terrain of this book by looking at how esports audiences have developed from a space where the line between player and spectator was quite blurry to a more formalized boundary akin to traditional broadcast frames. Drawing on work by Jack Bratich (2005) and Shawn Shimpach (2008), he argues for understanding esports and live streaming audiences within a framework that recognizes the “extent to which our participation in contemporary media forms is circumscribed” (2016, 304). His examples of how esports audiences at events are positioned in ways that serve to enhance media productions or amplify the affective side of tournaments (for example, in building “hype”) are instructive for helping us think about the ways these emerging audiences are woven back into productions in fairly constrained ways.28

So how to thread this needle? How should we understand the active work of live streaming audiences within a distinctly commercialized sphere of new media development? Rather than shy away from arguments about the commodification of audiences and the labor they engage in, or write off that engagement as simple exploitation or hollow participation, we need to understand how audiences are often knowing participants in the construction of new media forms, even ones for sale. Live streaming audiences are not dupes, though they may not always fully wrangle with the extent to which their engagement is a market commodity or the long-term costs.

In large esports broadcast events, there are absolutely moments when we might turn a critical eye to the ways that tournaments facilitate the production of an audience for broadcast and commercial purposes. The cameras that turn back on spectators show them wearing team jerseys or game hats, and play up the mass of the crowd. The handing out of “thunder sticks” and white poster board for signs—all of which let audiences create visually compelling, booming, and often-flashing cheers—are prime fodder for the camera. And yet at the same time we have to balance such accounts with the genuine passion, fandom, and authenticity of expression at work in the space. Esports audiences are often knowingly and meaningfully engaged as fans happy to support their scene, including the commercial entities involved. They regularly acknowledge the tension and are often highly attuned to coarse cash grabs.

And in variety streams where audience members are frequently deeply supportive of and connected to a broadcaster, understanding this balance requires even more care. Though both broadcaster and audience member are certainly “at work” in some way (as I’ll detail more later), and contributing to the financial health of the platform—including even just as data points, statistics that fill up business PowerPoint decks and press releases—they are usually knowing, intentional, and still striving for meaningful creativity and connection. Even as the platform leverages the affective pull of live streaming, we would be remiss to write it off as simply about exploitation.

Media is ultimately co-constituted through spectators, producers, and texts, and seeing it as relational is key. Jenkins has called for “refusing to see media consumers as either totally autonomous from nor totally vulnerable to the culture industries.” As he maintains, “It would be naive to assume that powerful conglomerates will not protect their own interests as they enter this new media marketplace, but at the same time, audiences are gaining greater power and autonomy as they enter into the new knowledge culture. The interactive audience is more than a marketing concept and less than ‘semiotic democracy’” (Jenkins 2006b, 136). His encouragement to document these circuits is an inspiration for the work here. While in the following I will speak more directly to issues around labor, precariousness, and affective economies as well as critically reflect on how engagement is regulated, the analysis is anchored in a model that sees audience engagement and co-creation as central to the story, and my frame is one in which commercial platforms like Twitch occupy complex, often-ambivalent positions within the broader circuit of production and sit alongside often-knowing, meaningful, user engagement.

Building a Platform

PAX East, while not the original flagship convention that takes place in Seattle, is a tremendous weekend event. Tens of thousands of people come to the Boston Convention Center to celebrate, discuss, and play analogue and digital games as well as participate in fan and celebrity panels, hyped-up developer sponsored demos, and amazing cosplay (costumes based around characters). Given that I was living just across the river in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it was easy enough to pop over, so in 2013 I attended my first PAX and had a chance to check out the Twitch booth.

Descending the escalator to the large exhibition hall can be an overwhelming experience. Lots of noise, lights, booths, and crowds fill the space. I knew enough to scan while I had a bird’s-eye view and spotted the Twitch booth off to the right, lit in its ubiquitous “Twitch Purple” hue. Its space that year featured a broadcast area with sofas for interviews and gaming with various personalities, a small demo area that focused primarily on Smite (a multiplayer game it was hosting a tournament for), some standing room, and several large screens to watch the ongoing broadcast. While not the largest booth there, it still took up a good chunk of floor space, and you could sense the company was figuring out how to showcase itself at an event otherwise dedicated to game developers and fan merchandise.

When I returned to the convention in 2014, it was clear that more was being done to make the booth a place to watch the broadcasts that were being piped out worldwide as well as hang around and mingle with others. Large screens were hung around the booth, drawing crowds to watch both the live on-site performers and the production that was being broadcast online (see figure 2.5a). This was no small detail. Twitch had secured a deal with ReedPOP, the event services company that produces the PAX expos, to be the exclusive streaming partner for the event. This meant that the company would not only be featuring content each day as in the prior year (hosting streamers and developers, for example). It was now the site to go to for PAX East coverage if you weren’t able to attend but wanted to keep up with the event. The booth was also the location for the Capcom Pro Tour fighting game competition and the TeSPA Collegiate Hearthstone Open (see figure 2.5b).

FIGURES 2.5A AND 2.5B. Audiences hanging out at the Twitch booth and watching fighting game competitions, PAX East, 2014.

Although the competitions definitely caught my eye, the thing I noticed most that year was that the booth became a hub where people congregated to meet others who used the platform. Name tags were available for everyone to note their Twitch username on. One popular streamer described his PAX experience this way:

It was more of a networking situation for me, and a time to meet with some of the personalities or some of the friends I’ve made, other streamers, and to be able to meet my viewers. I hang out and get to know these people. There was crazy happenstance meetings that we couldn’t plan. Just being around the convention I ran into people that have led to other relationships that are opening up doors for me. It’s just being around and being part of the community. And when I say community, now I’m talking about a much broader community, which is the Twitch community.

Being at the booth became an important part of the convention work and fun for many streamers. Broadcasters were meeting Twitch staff and each other—often face-to-face for the first time—and just as important, fans were swinging by to catch glimpses of their favorite personalities. Some of those streamers held a microcelebrity status; though likely not recognized outside the convention hall, inside they were experiencing their reach for the first time as people approached them to introduce themselves, say how much they loved their stream, and get a photo with them. Others got an additional notoriety bump as Twitch invited them onto the stage to help host sponsored game sessions.

As I hung around that booth for the weekend, I saw the beginnings of a fan culture emerge not around a game but instead around broadcasters. While the concept of cultural intermediaries—a class of professionals who promote the consumption of symbolic goods and services—can at times be resonant in understanding game live streaming, it also doesn’t fully capture things.29 Media scholars Sean Nixon and Paul du Gay (2002, 498) argue that the often-implied denigration of intermediaries or overly simplistic conservatism assumed in the concept (that they merely act as promoting given cultural artifacts) might cause us to overlook the more complex interplay of production and consumption, creative action, and the “interdependence and relations of reciprocal effect between cultural and economic practices.” These broadcasters were not only doing the work of bringing games to audiences but also had themselves become valued creative producers. They didn’t simply promote games, though that is a frequently implied part of a broadcast, but were doing something more as well. Game scholar Austin Walker (2014, 438) describes this expansive work of broadcasters as one in which “new communities grow around these streamers which sometimes offer an alternative to consumption-oriented ‘gamer culture,’ which work to bring attention to social and political concerns, and which highlight the work of independent and underrepresented developers, organizations, and groups.” Seeing them at PAX East, in the mix of game culture broadly, and interacting with each other and their fans, it became clear that they were “talent” who were transforming play. They were also helping build a budding industry that was (and is still) trying to situate itself within a larger game and media ecology.

Over time, this theme was picked up and integrated in earnest into the design of the booth. A dedicated area was constructed for streamers to meet their fans and give autographs. Special trading cards and various other swag were made for the broadcasters to hand out (see figures 2.6a, 2.6b, and 2.6c).

FIGURES 2.6A, 2.6B, AND 2.6C. Meet and greet, VIP area, and broadcaster novelty card at Twitch booth, PAX East, 2015.

A large internal VIP and meeting area also became part of the booth, where Twitch employees, partnered streamers, and assorted visitors could mingle. By 2016, the Twitch booth at PAX East had become the largest on the show floor and a huge hub of activity. Its presence and growth at the convention mirrored its overall development. In just a few years, Twitch had gone from a small site that offered gamers a way to experiment with sharing their play with strangers to a prime anchor in game culture; it became a place where taste and gameplay were shaped, and where gamers and their spectator fans rose in prominence alongside the titles they played.

It’s important, however, to not overlook the real challenges associated with such rapid growth. Live streaming platforms have faced tremendous technical, operational, and economic issues. It is no small feat to build out worldwide infrastructure, navigate how to monetize it, and manage all the people participating, creating, and sustaining a live streaming platform with millions of simultaneous users. This is a crucial part of the story, not just for live streaming, but UGC platforms broadly. It is easy to focus on creative individuals—perhaps you remember Time naming “You” the 2006 person of the year for all the content “we” were producing online—and bypass exploring how technological development, organizational structures, or financial systems are central to online life.

In the following, I focus on Twitch itself as an organization and platform as well as an actor that serves as one node in a larger process of cultural co-creation. Game live streaming is only possible via a complex assemblage of technologies, networks, economic models, and governance processes. All these aspects are important to telling the broader story that connects up with individual and organizational practices in the chapters to come. While I’ll be weaving these threads throughout the rest of the book, in the remainder of this chapter I present a bit of history about the company, tracing its beginning as a niche live streaming site to one of the major figures in not only the gaming but also the media industry.

ORIGINS

Twitch’s roots are fundamentally in the cam culture I described previously. Its origins spring from predecessor Justin.tv, a website dedicated to allowing people to broadcast anything and everything. Launched March 19, 2007, by roommates Justin Kan, Emmett Shear, Michael Seibel, and Kyle Vogt, the platform was geared to “lifecasting,” which essentially meant providing a website for people to pipe out their live video to others.30 As Shear described their intent in a Fast Company article, “We were going to enable this new form of reality TV based on streaming people’s lives 24/7, and that was going to be the business. We were going to be reality-TV moguls” (quoted in Rice 2012). With an initial investment of $50,000 by Paul Graham of Y Combinator, and less than a year later $2 million from Alsop-Louie Partners, the platform offered people the opportunity to broadcast whatever they liked (ibid.).31 Kan himself wore a camera and streamed everything from coding sessions to sleeping, and “proclaimed what his new mission would be: ‘democratizing live video’” (quoted in ibid.). Though he ultimately found the prospect of constantly streaming his life untenable, the site drew in others who wanted to provide content.

Kan’s ambition was very much in sync with the cultural moment. Facebook launched just a few years earlier in 2004, then YouTube in 2005, Twitter in 2006, and both Tumblr and the iPhone came out in 2007. This was, without a doubt, an intense period where everyday life was being interwoven with network culture, where people were producing content for each other whether it was routine updates on their daily life or special videos. And it was no longer fringe as in the old cam days; lots of internet platforms were experimenting with giving people ways to share pretty much whatever they wanted, however they wanted.

Despite the ways that mundane life was becoming visible more and more online, Justin.tv didn’t seem to be sustaining content producers and audiences at the hoped-for level. As with many such platforms, the costs were supposed to be defrayed through ad revenue. Yet such a model required advertisers to relinquish a fair amount of control over what their brands would be embedded next to. As journalist Andrew Rice (2012) notes, “Even when the site was thriving, advertisers were wary of the unpredictability of live user-generated video. So were potential investors and buyers for the company.” The potential volatility of allowing users to create all the content for a site is an important challenge that platforms have had to navigate and manage. Alongside this was Kan’s own ambivalence, having grown both weary of constantly streaming himself and “struggl[ing] to find anything worth watching” on the platform (quoted in ibid.).

There are slightly varying ways the story of the shift of focus to gaming that propelled Twitch to emerge is told. I was fortunate to be able to interview Shear, Twitch’s CEO, in 2013, and he spoke compellingly about how, when it came to Justin.tv, the gaming channels on the site were the ones that really caught his attention. Shear regularly speaks about his own gaming roots in interviews, and during our conversation he made a point that deeply resonated with my own thinking: there is an important historical continuum at work in live streaming. He observed,

The way I think about [it] is I spent three-quarters of my childhood watching video games as a spectator. In fact, almost every boy my age and most of the girls did this, because if you think about it, we had one console, the person playing the game, and when they died, the next person took a turn. So there were probably three or four of us at any given time sitting there, and you’re only playing a quarter of the time . . . and so in that way Twitch is not really all that new.

As he went on to explain, what we were seeing through live streaming was simply a “recapitulation” of these connections. The figure of an isolated gamer playing alone in their home was “the new weird thing,” not this (Shear 2013). Live streaming was an extension of the sofa space so many were familiar with.

This connection between being a gamer and seeing the power of the platform was something I heard often in my years visiting Twitch and speaking to people who worked there. Identifying as a gamer and remembering earlier moments of spectating play were consistent threads in what motivated the people building the site early on. This is not unusual in game-focused companies, where being an active gamer, even of the specific titles of the developer you are employed by, is a common part of one’s professional identity.32 Much development in that space comes directly from imagining yourself as the user, from projecting your experiences, pleasures, desires, and values onto the technology. Early Twitch innovation was deeply tied to executives and developers who were also identifying as gamers.

There is, however, a second significant thread in Twitch’s development story: the powerful role of media piracy. Since its inception, the internet has facilitated free and sometimes-illegal access to media. Music distribution and early skirmishes around software like Napster helped set the tone that traditional media companies have taken decade after decade: regulation, enforcement, and technological interventions via digital rights management when possible.33 With the growth of peer-to-peer distribution networks as well as broadband access, the ability to share larger and larger files such as movies and television shows also grew. It should not be surprising, then, that live streaming afforded yet another new path for media content distribution, including piracy.

Justin.tv, along with a number of other sites such as Stickam and Ustream, became a platform where people could rebroadcast live events, particularly sports. Everything from the National Football League (NFL) and Major League Baseball (MLB) to Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) games could be found online in real time. Exclusive broadcast deals (frequently via pay cable channels), blackout zones, and stringent licensing has contributed heavily to sports fans seeking out pirated channels to get games—often ones that they might not otherwise have access to. In an early piece analyzing sports rebroadcasting online, Bruns (2009, 2) described how Justin.tv users addressed a lack of media access through “following a ‘gift economy’ logic: they rebroadcast what sporting events are readily available to them on their local TV channels, and in turn profit by being able to watch the sporting events rebroadcast by fellow users from elsewhere in the world.” The tensions between global online media and local regulations come into sharp relief via these platforms. Communication researchers Burroughs and Rugg note that despite the global frame that television typically circulates within, broadcast rights and regulations tend to still be done on a nation-by-nation basis, and fans regularly leverage a range of technologies (from live streaming to virtual private networks) to get around geofencing (virtual perimeters that regulate access to content by geographic location). They ask us to think about it as a tactical challenge to “the ‘proper’ strategies of mass consumer and television culture” (Burroughs and Rugg 2014, 370).34

This practice, unsurprisingly, did not go unnoticed; media companies and lawmakers got involved. The British Premier League had threatened Justin.tv, and a boxing company had sued Ustream previously (Roettgers 2009). In 2009, a House Judiciary hearing titled “Piracy of Live Sports Broadcasting over the Internet” was held to investigate the situation. Witnesses were called from the MLB, the UFC, ESPN, the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and Justin.tv. Seibel, CEO of Justin.tv at the time, testified before the committee, offering a story of the platform’s place in the emerging networked world as well as its position on the content there. He began by noting that