Chapter 5. New Recombines with Old

WEB 2.0 MAY APPEAR TO BE SOMETHING NEW, DIFFERENT, AND INCOMPATIBLE with business platforms that came before. Although much of the point of this book has been to show that Web 2.0 is different, that difference doesn’t mean that the old world halts and a new world begins.

Web 2.0 strategies can be a component of other business models. One common option is to build communities on the basis of existing products and brands. Another is to build relationships between up-and-coming firms with new technologies and older companies with experience in a field and a strong user base. Along the way, businesses can explore new relationships with their customers and with each other.

Styles of Innovation

Even before economist Joseph Schumpeter described innovation as the “creative winds of destruction” back in 1942, businesses have feared the dark side of innovation. New technologies disrupt the old order and destroy the comfortable relationships, profitable markets, and leadership positions that current companies—called industry incumbents—have successfully carved out for themselves through years of investment and infrastructure. Clayton Christensen’s bestseller, The Innovator’s Dilemma (HarperBusiness), reminded even high-tech winners that innovation comes in disruptive waves from emerging technology niches and ignored market segments, making today’s heroes next year’s zeros.

Using the disk drive as an example, Christensen defines disruptive innovation as a “sleeper” technology that poses an unanticipated threat to industry incumbents, as the new entrants initially satisfy only the requirements of a niche or an emerging low-performance, low-end market. Thus, established firms—even those that are quite capable of the new technology—are led to complacency and inertia by their own mainstream and premium customers, until it’s too late.

Of course, that is not quite the story in digital and online networked technologies or in disruptive business models that change the way businesses make money and cover costs in an increasingly connected online, mobile “flat world.”

Amazon.com certainly did not start with low performance when it immediately attacked the mainstream mass market for books and quickly moved to a range of retail products and affiliate storefronts.

Digital cameras started out more expensive than film cameras of similar performance but held out the promise to all recreational photographers of lower lifetime usage costs because film and development could be replaced by digital images, distribution, sharing, and storage.

Skype and peer-to-peer (p2p) architecture for Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) offered free basic or low-end service, but they targeted and reached a global mainstream and business market through viral marketing and distribution (allowing users themselves to be the routing hub for their international calling rolodex).

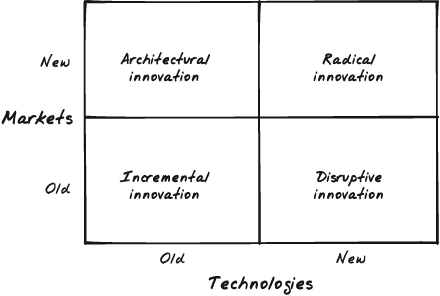

For the purposes of this chapter, we will start with a simplified 2 × 2 innovation typology, shown in Figure 5-1, that positions disruptive innovation (or, as it used to be called, “revolutionary innovation”) along the axes of old-new markets and old-new technologies.

Clearly, new technologies that capture old or existing mainstream markets are disruptive—a bit like revolutionaries who turn the entire population against the old order. But for the mainstream market to move wholesale to a new way of doing things, a large population must believe that it’s worth switching—and that the basis of competition and of how people are measuring and comparing value has changed.

It’s easy to place incremental innovation and radical innovation in this matrix. Incremental innovation is old technology in old markets; radical innovation is new technology in new or emerging markets. Finally, we have architectural innovation, old technologies in new markets, recombining and repackaging existing technologies within redesigned system and product architectures to reach new market segments and niches. Scholars have used these terms for decades to categorize the kinds of technological innovations that cause shifts in the competitive landscape and the relative profitability and market share of incumbent firms compared with new entrants.

Of course, whether one views these innovations as “world-saving” or “creative destruction” depends on where she sits. Specifically, if any of these kinds of innovation or technologies is competence-enhancing and increases the value of the organizational and intellectual assets a company already has in-house, she is likely to be a cheerleader. However, if one of these technologies is competence-destroying and destroys the value of the organizational and intellectual assets a company possesses, she is likely to be a defender and will do her best to eliminate, strong-arm, or legally wipe out these threats. This is the typical zero-sum, win-loss battle between the incumbents, who have a lot at stake, and the new entrants, who have everything to gain.

However, Web 2.0 and its particular brand of collaborative, digital, and online networked/interactive user-led innovation doesn’t fit neatly into this conventional 2 × 2 competitive innovation matrix. That isn’t surprising, as these innovation categories were coined to describe technological breakthrough innovations in the physical world of disk drives, semiconductors, steel mini-mills, photolithography equipment, and manufacturing processes. In the following sections, we’ll discuss some newer categories of online digital networked collaborative innovation that are breeding disruptive business models in high- and low-tech industries.

Competitive or Collaborative Innovation?

A few industries—media, telecom, and banking, among others—seem to stay above the competitive fray. Initially, these industries were well protected from the turbulence of emerging technologies, pure-play competitive startups, and global new entrants. Governmental regulations, high barriers to entry through committed investments in irreplaceable and costly infrastructure, complex contracting structures, and relationships combined with strong and enforceable property rights had, to this point, insulated them against the changing landscape.

Yet in erecting walls against all possible disruptors and competitors, while assuming away the option to become network partners and ecosystem allies, the companies in these protected and highly regulated industries may have been mistaking the good Dr. Jekyll for the evil Mr. Hyde.

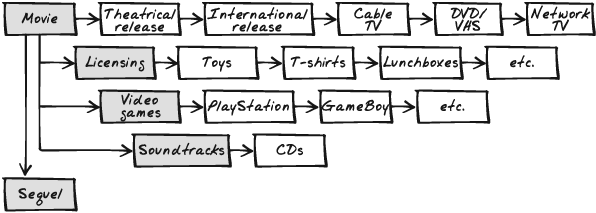

In the early 1980s, during the advent of videocassette recorders, the movie studios fought major legal battles to try and stop home recording and video rentals. So, at first, studios priced their movies so that rental stores could afford to buy only a few copies, disappointing many customers who wanted new and popular releases. Of course, with the high video prices and artificial scarcity of video rentals, “cannibalism,” or eating into live-at-the-theater big-screen profits, was reduced. It took 15 years to see that the actual outcome of the new videocassette recorder technology was to enormously expand the entire market. In 1980, industry revenues from both big screen and video were $2.4 billion, by 1995, the market was $12.3 billion, with home video rentals bringing in $7 billion.

Figure 5-2 shows the multiple revenue streams and network effects that are now possible for movie studios with online and digital distribution. The challenge for the movie studios has changed from creating blockbuster movies and distributing them through a limited physical channel of distribution—the movie theater—toward more effective monetization and value capture of the expanded digital distribution market in cable pay-per-view, DVDs and rentals, network TV, video games, music soundtracks, and other potential syndication, licensing, and remixing opportunities.

Another example comes from e-commerce. It would be easy to see offline independent and chain bookstores as strict competitors of online booksellers like Amazon. However, just like the video story, sales in one domain seem to produce a “lift” in the other, and vice versa. The key to Netflix, Flickr, Amazon, and other online companies is that the sales of offline physical products can get online “buzz.” These online sales, referrals, rankings, and reviews enjoy a wider and more targeted word-of-mouth marketing, creating a chain reaction or critical mass of adoption and social influence.

Even when industry leaders recognize a potential network partner or ecosystem player, they will sometimes turn down the opportunity in order to protect their own cash cows or maintain control of their “walled garden.” In the financial world, this could be one of the explanations for why, of all the major retail banking centers in the world, only Japan had a different magnetic strip on its credit cards that made the cards usable only at Japanese ATMs. It certainly seems to have been why Citibank, the first bank to introduce and invest in the ATM infrastructure back in 1977, waited until 1991 to allow its ATM cards to work on other banks’ ATM networks. A simple analysis of indirect network effects would have shown that everyone’s ATM cards are more valuable when they work on all machines.

At least some of the explanation of Europe’s surprisingly strong recent economic health comes from both the European Union and the euro with its integration and positive network effects compared with the once-independent currencies and fragmented markets of the European nations.

PayPal’s person-to-person online payment system, piggybacking on the hypergrowth and the success of eBay’s online auction transactions, was viewed as a startup competitor rather than a potential ally by the major banks that wanted to protect their finely tuned and highly profitable SWIFT cross-border and inter-bank system for wire transfer of funds. (Several of them tried to develop their own person-to-person online payment systems.) PayPal’s system never reached a critical mass of networked online users because it lacked the visibility and daily volume of n-sided market transactions of an online partner like eBay. Not surprisingly, eBay acquired PayPal in 2002, listening to its customers who preferred it over eBay’s homegrown system.

The key is that allies and ecosystems can join forces in expanding and opening up markets to create a win-win situation. Competitors and a competitive perspective on innovation tend to divide markets and leave a lot of potential expanded network-effects value and opportunities on the table.

Styles of Collaborative Innovation

In the new-style online collaborative innovation, the entire perspective of innovation changes. We move away from a situation in which new and old companies compete in an industry for competitive advantage in capturing new and old markets using different kinds of innovative technologies. Instead, we have big and small companies whose users collaborate, often across industry boundaries, in innovative ways. So, the fundamental axes of the collaborative innovation matrix are different from those of the competitive innovation matrix.

The styles of collaborative innovation are distinguished by whether the collaborative interaction is between

Crowds of users, called user-led or democratized innovation.

Crowds collaborating to solve problems for companies, called crowdsourcing.

Companies that provide new platforms on which innovation communities and ecosystems can form, including open source, ecosystem, and platform innovation. This yields a number of different paths for innovation, as shown in Figure 5-3.

Democratized Innovation

Eric von Hippel’s book Democratizing Innovation (The MIT Press) observes that lead users often develop and modify products for themselves and freely reveal what they have done so that others can adopt the developed solutions. He calls the trend toward these primarily user-centered innovation systems the “democratization of innovation.”

As open source software projects show, horizontal or peer-to-peer innovation communities, consisting entirely of users, can function as self-organizing and regulating entities without manufacturer or corporate involvement. So, the keys to democratized innovation in the online collaborative world are the wide distribution, ease and low cost of tools for innovation, combined with the tools for interaction and communication. Peer interaction and recognition between users catalyze innovation, personal expression, and creativity. The Linux open source community is a good example, says Chris Hanson in Democratizing Innovation:

Creation is unbelievably addictive. And programming, at least for skilled programmers, is highly creative.... Community standards encourage deep understanding.... For many, a free software project is the only context in which they can write a program that expresses their own vision, rather than implementing someone else’s design or hacking together something that the marketing department insists on.... Unlike architecture, the expressive component of a program is inaccessible to non-programmers. A close analogy is to appreciate the artistic expression of a novel when you don’t know the language in which it is written...this means that creative programmers want to associate with one another: only their peers are able to truly appreciate their art...it’s also important that people want to share the beauty of what they have found....

Web 2.0 technologies such as RSS, wikis, podcasting, and social networks increase the intensity, frequency, and ease of online collaboration and community-building.

Crowdsourcing Innovation

Crowdsourcing or crowdcatching is a problem-solving and idea-generating process in which a company throws out a well-specified problem to a selected crowd or group of people for solution. Some well-known crowdcasts are in the form of competitions—prizes are used as an incentive, and the “winning” solutions are chosen by a set of judges. It provides a focal point for the “wisdom of the crowd” to emerge from unexpected and interdisciplinary sources and individuals.

Let’s start with a simple framework used by economists for analyzing knowledge as an economic good and apply it to the recent case of Goldcorp, a company in the “old-economy” mining industry. Rob McEwen had become the CEO of Goldcorp, a low-yield Canadian gold-mining operation, when the gold market was depressed, operating costs were high, and the miners were on strike. “Mining is one of humanity’s oldest industrial pursuits. This is old old economy. But a mineral discovery is like a technological discovery. There’s the same rapid creation of wealth as rising expectations improve profitability. If we could find gold faster, we could really improve the value of the company.”

McEwen realized that if he could speed up the “knowledge production” process—to find new ideas about where to dig for high-grade ore on his property faster—he could turn around his failing company. Most companies use three conventional forms of knowledge production:

R&D knowledge production in company and academic labs focused on basic research or applied research

Learning-by-doing, involving lead users and communities of practice

Integrative or coordinative knowledge including standards and platforms

McEwen needed results fast. He recalls that his “eureka” moment came as a result of a seminar at MIT in 1999, where he first heard about the impact of the Linux operating system and the open source revolution. Here was an unconventional and revolutionary approach to speeding up the “knowledge production” process without costly long investment cycles or big, risky bets. “I said, ‘Open source code! That’s what I want.’” After all, if Linux could attract world-class programmers to help make better software, maybe Goldcorp could attract world-class geologists to help find gold. McEwen issued the Goldcorp Challenge in March 2000—Goldcorp revealed all of its geological data regarding their Red Lake gold mine online, asking geologists to tell them where to find 6 million ounces of gold. The prize money totaled $575,000; the top award was $105,000.

More than 1,400 virtual “prospectors” joined the Goldcorp gold rush and downloaded company data. Like alchemists, many of the final contest winners turned Goldcorp’s raw information and data into actionable knowledge about where to dig for gold. McEwen says that the contest was a major success: “We have drilled four of the winners’ top five targets and have hit on all four.” Additionally, the discoveries have been high-grade and high-yielding ore deposits. “But what’s really important is that from a remote site, the winners were able to analyze a database and generate targets without ever visiting the property. It’s clear that this is part of the future.” Making the data available for download on the Web, allowed scientists, engineers, and geologists from 50 countries to participate, and the panel of 5 judges could evaluate and compare the creative approaches and targets of an astonishingly diverse set of submissions.

The numbers speak for themselves. In 1996, the Goldcorp Red Lake mine was producing at an annual rate of 53,000 ounces at a cost of $360 an ounce. After the contest and some modernizing in 2001, the mine was producing 504,000 ounces, about 10 times more, at a cost of $59 an ounce. With gold prices at $307 an ounce, that’s like $248 in profit per ounce rather than a $53 loss per ounce.

The mining industry as a whole has benefited. As Michael Polanyi pointed out in his book Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy, personal knowledge or “tacit” knowledge such as riding a bike, scoring soccer goals, or intuiting where to dig in 55,000 acres of Red Lake property is usually hard to transfer or reproduce. But any of us can make the effort to deliberately share and transfer this kind of knowledge and skills to others by “codifying” it in a formula, script, program, model, expert system, demonstration, or recording.

The problem comes when the inventor or idea originator wants to get paid. Once knowledge is produced and codified, as in a mathematical formula or digital code on the Web or video, it becomes fluid (an economic good that is difficult for the creator to control privately), “infinitely expansible” (like the Energizer bunny, it doesn’t get depleted by usage), and cumulative—leading to a combinatorial explosion of social and public goods. This benefits many individuals and companies through knowledge “spillover,” but it may or may not result in profit or payment to the sponsoring company or to the generators of the idea and the knowledge. Thus the term “externality” applies when an economic good produces positive or negative effects (value or noise) that cannot be captured or “internalized.”

An online contest can turn out to be an unexpected solution to the externality problem. According to Ronald Coase in his article “The Problem of Social Cost,” in the Journal of Law and Economics, and explained in Dominique Foray’s The Economics of Knowledge (The MIT Press), the size of the externality can be reduced by expanding the area in which knowledge is voluntarily shared. So, the collective production of knowledge in technology consortiums, multicompany research centers, and R&D agreements can be used to “internalize externalities.” Before the Web, coordination and organization costs made a very large number of knowledge-sharing partners infeasible.

The Goldcorp contest was well organized to allow the company to immediately judge the value and quality of the submitted ideas and mining targets and then pay the contest winners a fixed amount for their contribution. In economic terms, this provided a fixed incentive for the contest participants as well as a way for Goldcorp to internalize or monetize the virtual gold rush through actual mining operations.

In the Goldcorp Challenge, the top contest winner was a partnership of two Australian groups (Fractal Graphics and Taylor Wall & Associates) that developed a powerful 3-D graphical model of the mine. Winning the prize gave publicity to the firms’ competence in 3-D models of mines, and according to Nick Archibald at Fractal Graphics, the industry now has a new way of doing exploration. “This has been a big change for mining. This has been like a beacon in a sea of darkness.”

In short, Goldcorp struck gold on the Web by:

Accelerating relevant “knowledge production” (on where to dig for gold) by world-class experts at a relatively low fixed cost (total prize money was $575,000).

Incentivizing “collective production of knowledge” by making its company-proprietary (but raw) data sets available to download for the contest, while maintaining sole rights to mine and exploit the knowledge generated about target sites.

Capturing knowledge spillover and cumulative learning across a range of disciplines by reviewing, judging, and evaluating the diversity of approaches and then testing the target sites.

Monetizing the winning models immediately by exploring the mining targets and paying, publicizing, and promoting the contest winners.

The web sites of the Innovation Challenge, World Bank Development Marketplace, X PRIZE Foundation, Goldcorp Challenge, Bayer Material Science Prize, Netflix Prize, Ansari X PRIZE, Innocentive, and Red Hat Challenge illustrate the range of companies, industries, and technologies experimenting with crowdsourcing innovation.

It doesn’t even require a well-publicized contest. The blog Billions With Zero Knowledge (http://www.billionswithzeroknowledge.com/) uses the T-shirt company Threadless as an example of creative design-intensive community production that seems to be much more powerful and innovative than just “crowd-sourced manufacturing.”

Open Source, Ecosystem, and Platform Innovation

Companies have adapted to user-centered innovation in different ways. Several authors have described how companies have innovated by providing platforms from which externally generated innovations can result, and where users—as well as ecosystems of affiliates, third-party developers, and service providers—can form innovative communities.

After reviewing some definitions and examples, we’ll discuss a more recent and wildly popular platform innovation: Apple’s iPod and the ecosystems that have developed around it. Although the iPod does not use a Web 2.0 business model, it illustrates how companies can capture and multiply network value from ecosystems and passionate, loyal users.

Steve Weber’s The Success of Open Source (Harvard University Press) explores how open source catalyzes innovation and enlarges the scope and scale of knowledge domains because “property in open source is configured fundamentally around the right to distribute, not the right to exclude.” He echoes Larry Lessig’s well-known argument that a “commons” functions as a “feedstock for economic innovation and creative activity.” But he adds a more nuanced innovation benefit: the importance of DIY participation in creative activity by individual users, simply for the sake and value of the individual or community creative act—even if this participation is not immediately measurable as an increase in knowledge stocks or directly related to a breakthrough innovation.

Marco Iansiti and Roy Levien’s The Keystone Advantage (Harvard Business School Press) argues that the very best companies are “keystones” or orchestrators of their ecosystem or “value network”—their large and distributed network of partner companies and customers. They use the examples of Wal-Mart, Microsoft, and Li & Fung to show how keystone companies provide “platforms” that other firms and users can leverage to spur innovation.

Geoff Moore, the best-selling author of Crossing the Chasm and recently Dealing with Darwin: How Great Companies Innovate at Every Phase of Their Evolution (Portfolio Hardcover), coined the term platform innovation. In his blog (http://geoffmoore.blogs.com/), he refers to Intel’s shift from microprocessor products to all-purpose mobile computing and communications platforms and devices as a good example of platform innovation. The key is to leverage a potentially ubiquitous product or device into a market-making, online distribution platform and channel.

The biggest challenge to companies innovating in this area is to convert from an engrained culture of competition to the collaborative culture necessary for creating trusting relationships and developing myriads of new partners and ecosystems. It’s not easy for a company like Intel—whose chairman and former CEO Andy Grove wrote a book titled Only the Paranoid Survive (Currency) and rose to power as a take-no-prisoners competitor—to turn around and preach “Give to get.”

Online Recombinant Innovation

The recombinant DNA techniques discovered in 1973 founded genetic engineering and sparked a biotechnology revolution. Recombinant DNA emerges from new combinations of DNA molecules that are not found together naturally and are derived from different biological sources. In an analogous way, innovation that shows recombination or new combinations of different companies’ technologies, processes, systems, and business models can be termed recombinant innovation to differentiate it from innovation that comes from only one company and source.

Bridging, Not Disrupting

Rather than rebelling against or completely disrupting the old business order and replacing the infrastructure that took decades of development and investment, the new click-and-mortar, online-offline network partnerships are recombinant business model innovations. They focus on building new networks and business models based on collective user value and hypergrowth social network opportunities.

Integrating Ecosystems: Apple’s iPod

Apple’s iPod is not precisely a web application. At its heart, it combines iPod hardware for playing music (and pictures and video), iTunes software for managing that content (shown in Figure 5-4), and an iTunes store that runs over the Web (shown in Figure 5-5). The iPod exemplifies the integration of new technology with existing systems, and its continuing growth into new areas (such as the web-capable iPhone) demonstrates how different technological ecosystems can coexist. Physical hardware can both benefit from network effects and create surrounding businesses based on those effects.

However, the iPod combines much more than just components made and controlled by Apple. The first four ecosystems we’ll discuss are illustrative examples of platform innovation, and they demonstrate how Apple has captured value from its ecosystems and expanded and widely distributed this value to its partners. You’ll see the overall increased returns from collaborative innovation.

In this example, a lead company—here, Apple—conceives, designs, and orchestrates the external innovation and creativity of many other outside participants, users, suppliers, creators, affiliates, partners, and complementors to support an innovative product, service, or system. The final (and fifth) ecosystem—the iTunes and major record label partnerships—is used as a contrasting example of recombinant innovation and will be discussed later.

Platform Innovation Ecosystem #1: Production

To create the iPod, Apple first assembled a production ecosystem—a group of companies all over the world that contributed to circuit design, chipsets, the hard drive, screens, the plastic shell, and other technologies, as well as assembly of the final device.

Although many people still think of the manufacturing process as the key place to capture added value, the iPod demonstrates that Apple—the creator, brand name, and orchestrator—has actually figured out how to capture the lion’s share of the value: 30%. The rest of the value is spread across a myriad of different contributions within the network of component providers and assemblers, none of them larger than 15%. Researchers, sponsored by the Sloan Foundation, developed an analytical framework for quantitatively calculating who captures the value from a successful global outsourced innovation like Apple’s iPod.

Their study (http://pcic.merage.uci.edu/papers/2007/AppleiPod.pdf) traced the 451 parts that go into the iPod. Attributing cost and value-capture to different companies and their home countries is relatively complex, as the iPod and its components—like many other products—are made in several countries by dozens of companies, with each stage of production contributing a different amount to the final value.

It turns out that $163 of the iPod’s $299 retail value is captured by American companies and workers, with $75 to distribution and retail, $80 to Apple, and $8 to various domestic component makers. Japan contributes about $26 of value added, Korea less than $1, and the final assembly in China adds somewhat less than $4 a unit. (The study’s purpose was to demonstrate that trade statistics can be misleading, as the U.S.-China trade deficit increases by $150—the factory cost—for every 30 GB video iPod unit, although the actual value added by assembly in China is a few dollars at most.)

Suppliers throughout the manufacturing chain benefit from sales of the product and may thrive as a result, but the main value of the iPod goes to its creator, Apple. As Hal Varian commented in the New York Times:[32]

The real value of the iPod doesn’t lie in its parts or even in putting those parts together. The bulk of the iPod’s value is in the conception and design of the iPod. That is why Apple gets $80 for each of these video iPods it sells, which is by far the largest piece of value added in the entire supply chain.

Those clever folks at Apple figured out how to combine 451 mostly generic parts into a valuable product. They may not make the iPod, but they created it. In the end, that’s what really matters.

Platform Innovation Ecosystem #2: Creative and Media

The iPod is also part of an ecosystem and contributes to the indirect network effects of Apple’s other key product: Macintosh computers. Even though iPods, and the iTunes software that supports them, were originally compatible with Macs only, the cachet of the iPod has continued to help sell Macs even after the iPod developed Windows support.

Beyond the iPod and iTunes, Apple’s creative and media ecosystem includes software such as iMovie, iDVD, Aperture, Final Cut, GarageBand, and QuickTime (a key technology for the video iPods). These are all Apple products, but many other companies also provide software and hardware for this space, notably Adobe and Quark.

Platform Innovation Ecosystem #3: Accessories

As any visit to the local electronics (or even office supply) store will show, the iPod has inspired a blizzard of accessories. Bose, Monster Cable, Griffin Technologies, Belkin, and a wide variety of technology and audio companies provide iPod-specific devices, from chargers to speakers. Similarly, iPod fashion has brought designers, such as Kate Spade, into the market for iPod cases, along with an army of lesser-known contributors. Also, automobile companies and car audio system makers are adding iPod connectors, simplifying the task of connecting iPods to car stereo systems.

iPod accessories are a $1 billion business. In 2005, Apple sold 32 million iPods, or one every second. And for every $3 spent on an iPod, at least $1 is spent on an accessory, estimates NPD Group analyst Steve Baker. That means customers make three or four additional purchases per iPod.

Accessory makers are happy to sell their products, of course, but this ecosystem also supports retailers, which get a higher profit margin on the accessories than on the iPod (50% rather than 25%). It also reinforces the value of the iPod itself because the 2,000 different add-ons made exclusively for the iPod motivate customers to personalize their iPods. This sends a strong signal that the iPod is “way cooler” than other players offered by Creative and Toshiba, for which there are fewer accessories. The number of accessories is doubling each year, and that’s not including the docking stations that are available in a growing number of cars.

Most industry participants were surprised by the strength and growth of the accessory market. Although earlier products such as Disney’s Mickey Mouse or Mattel’s Barbie supported their own huge market for accessories, those were made by the company that created the original product or by its licensors. Apple has taken a very different path, encouraging a free-for-all; it accepts that its own share of the accessories market is small, knowing that the iPod market is growing.

Platform Innovation Ecosystem #4: User-Provided Metadata

Even before the iTunes music store opened, users who ripped their CDs to digital files in iTunes got more than just the contents of the CD. Most CDs contain only the music data, not information like song titles. Entering titles for a large library of music can be an enormous task, and users shouldn’t have to do it for every album.

This problem had been solved earlier by Gracenote, which is best known for its CDDB (CD database) technology. Every album has slightly different track lengths, and the set of lengths on a particular album is almost always unique. So, by combining that identification information with song titles entered by users only when they encountered a previously unknown CD, Gracenote made it much easier for users to digitize their library of CDs.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, Apple simply connected iTunes to CDDB, incorporating the same key feature that made CDDB work in the first place: user input. Whenever a user put in a CD that hadn’t previously been cataloged, iTunes would ask that user if he wanted to share the catalog.

Apple has no exclusive rights to CDDB, but it benefits from its existence nonetheless. Users get a much simpler process for moving their library to digital format, and contributing to CDDB requires only a decision, not any extra work.

Recombinant Innovation

The music industry is perhaps the most difficult ecosystem the iPod has to deal with—and the most frequently discussed. The music industry has dealt with the Web and the Internet broadly as a threat rather than an opportunity, as it saw its profits disappearing when the transaction costs of sharing music dropped precipitously. So, how did Steve Jobs get the record labels—which had been suing Napster and Kazaa—to sign up for the iTunes store to offer online, downloaded music?

Apple presented its proposal to the big four music companies—Universal, Sony BMG, EMI, and Warner—as a manageable risk. Apple’s control of the iPod gave it the tools it needed to create enough digital rights management (DRM)—limiting music to five computers—to convince the companies that this was a brighter opportunity for them than the completely open MP3 files that users created when they imported music from CDs. Jobs was actually able to leverage Apple’s small market share into a promising position:[33]

Now, remember, it was initially just on the Mac, so one of the arguments that we used was, “If we’re completely wrong and you completely screw up the entire music market for Mac owners, the sandbox is small enough that you really won’t damage the overall music industry very much.” That was one instance where Macintosh’s [small] market share helped us.

Apple also played a key role in coordinating the pricing of songs among the big four music companies—99 cents a tune. This was a major step in weaning the music companies away from their high-priced retail distribution of prepackaged bundled digital goods— CDs—toward a digital distribution channel with a per-user/per-song revenue structure and potentially strong social-network effects. Downloads were also carefully priced to incentivize users who preferred having legal downloads and who trusted Apple and Steve Jobs to keep the price at that level despite the protests of the music labels.

After 18 months of negotiations, Apple was able to get started on its own platform, and later carry the DRM strategy to Windows. (One pleasant side effect for Apple of the DRM deal with the music companies is that it is difficult for Apple to license that DRM technology, preserving Apple’s monopoly there.)

Apple provided the music companies with a revenue stream built on an approach that would let them compete with pirated music, although the companies aren’t entirely excited about adapting to song-by-song models and the new distribution channels. However, EMI’s decision in April 2007 to start selling premium versions of its music without DRM—still through the iTunes store but also through other sellers—suggests that there is more to come in this developing relationship. Ecosystems evolve, and business ecosystems often evolve beyond their creators’ vision.

Working with the Carriers: Jajah

On September 15, 2005, the normally reserved Economist’s cover proclaimed, “How the internet killed the phone business.” The article heralded the end of the world’s trillion-dollar telecoms industry as Skype and other VoIP companies promised to make all phone calls free. Once Kazaa’s founders had been blocked from p2p file-sharing in the highly copyrighted music digital download arena, they turned that powerful viral distribution engine toward the Internet phone business, and aimed to make it profitable with a freemium strategy of charging business users to support free PC-to-PC calling for everyone else. The Economist article stated that “It is now no longer a question of whether VoIP will wipe out traditional telephony, but a question of how quickly it will do so...perhaps only five years away.”

Fast forward to a little more than two years later and the picture looks quite different. eBay has written off its acquisition of Skype, and Skype’s dynamic cofounders and serial entrepreneurs have moved on to disrupting the business models of yet another profitable industry—the media and video advertising industry—with their startup Joost.

Enter Jajah, a Web 2.0 voice telephony startup that seems to have taken a page out of Apple iTunes strategy playbook. Jajah partners and revenue-shares with local carriers to offer high-quality long-distance everywhere, using existing landline phones or cellphones. Calls between registered Jajah users are free, while long-distance calls to anyone else are at amazingly low local rates. In fact, its new service, Jajah Direct, assigns local numbers to all the long distance phone numbers in your online telephone directory so that you can call your family, friends, and colleagues overseas for almost the same cost as dialing a next door neighbor. Jajah routes long-distance calls over their own “backbone” infrastructure, allowing higher-quality service than the public IP system.

Jajah is breaking new ground in the mobile advertising arena as well. The challenge here goes beyond the usual relevancy and behavioral targeting. Jajah has to shape customer expectations in the emerging mobile, audio, and cross-media advertising areas. It’s easy to place Japan Air travel ads with callers who have a high volume of calls between the U.S. and Japan, but what does the ad say and when during the call? This is where the call-back system, described below, turns out to be an advertising opportunity. Phone callers don’t mind hearing a short ad while waiting to be connected at a low rate. And follow-up information can be displayed on the user’s account page, sent by SMS or opt-in to an email.

The User Experience

The Jajah calling experience is so convenient that 2 million users signed up for Jajah the first year, twice as many as Skype in its first year. There are more than 4 million users now worldwide. No special headset or phone equipment is required, and users are not tied to their computers or laptops. If you’re a frequent business traveler, you may have had the somewhat awkward experience of trying to have a Skype PC-to-PC call enroute to your gate while balancing your laptop on your carry-on luggage or a tiny telephone shelf. Like Flickr and other Web 2.0 companies, active, frequent users and independent bloggers created a critical mass and triggered a bandwagon effect. Interestingly enough, doing so little of its own marketing and advertising gave Jajah enormous credibility with users, both in the U.S. and overseas.

Jajah offers free calling between Jajah users. This provides a clear incentive for viral marketing—and encourages new users to bring their whole rolodex of friends on to the system. Soon IM (instant messenger) “buddy lists” will join as well.

Most frequently, a user will visit the company’s web site at http://www.jajah.com and schedule a Jajah call online, as shown in Figure 5-6. In a few minutes, or at the scheduled time, the user will receive a phone call on her phone or cell phone. When she picks up, a voice will greet her and inform her that Jajah is connecting her call. The caller should then hear the destination phone start to ring. During this call-ringing wait time, she may hear an ad message. As soon as the party at the other end picks up, the call is connected—for free if the destination phone is a Jajah user; for a minimal local charge if the destination phone is located in any of the 27 countries Jajah serves.

The web page also provides three-way calling, web-conferencing services, and the Jajah Direct feature. Blackberry and mobile phone users with Internet/broadband connections can call long distance and access Jajah phone services directly from their phones. Jajah also offers business services for operations like call centers.

Alliances Make It Work

Rather than promising to turn the telecom world upside down, Jajah worked together with large industry players that had already invested huge amounts in infrastructure, ecosystems, and customer relationships. This nonthreatening co-opetition approach avoids the backlash that occurs when entrenched or incumbent interests feel threatened by industry turbulence and disruptive technology.

Like with Apple and the major music labels, Jajah generates a new source of revenue for local carriers, rather than threatening to cut them out of the loop entirely, as Skype threatened to do. Deutsche Telekom, the owner of T-Mobile, has even invested capital in Jajah to grow and expand its Voice 2.0 services, along with Intel Capital.

More Recombinant Innovation: The iPhone

Lessons from both the iPod and Jajah fit well with Apple’s latest innovation, the iPhone. Apple applied the lessons it had learned from managing the iPod and iTunes ecosystems to the much-heralded June 2007 release of the iPhone, combining its own technology reputation with a partnership in a new field. Cellular provider AT&T Mobility distributed and provided a set of new service features necessary to showcase the phone’s unique user experience and touchscreen.

The iPhone itself is technically fascinating, combining updated iPod software with a new touchscreen and software that applies Apple’s user interface experience to users who are familiar with the Web and earlier cell phone designs. It offers many features beyond cell phone service, including web browsing and email over wireless networks (avoiding cellular data charges when browsing in places with cheaper service), multimedia viewing and listening, and viewers for typical computer data formats such as Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, and PDFs.

When releasing the iPhone, Apple chose to partner with a single cellular carrier, a decision that allowed it to have more control over the iPhone user experience. It generated some controversy as well as many efforts, some successful, to hack the phone so it would work with other providers. Currently, Apple needs to reach 10 million users to achieve a 1% market share in the cellular market; in the first three months after its release, Apple managed to sell one million iPhones—though it took a price cut. AT&T Mobility’s 63 million subscribers are a good market in which to achieve this goal, but a small share of possible cell phone users who might want an iPhone.

Of course, if the iPhone becomes usable over broadly-deployed Wi-Fi and WiMAX, a single cellular carrier might become a moot point. In September 2007, Apple released the iPod Touch, giving users the option of getting the iPhone’s features minus cellular service. That doesn’t do much for the cellular partnership side of this ecosystem story. However, it will certainly widen the reach of the iPod ecosystem—deepening its connections with the Web and with software developers who are willing to work through Apple’s web-based mechanism for extending the devices’ capabilities.

While AT&T Mobility will be the only U.S. service provider for the iPhone through 2009, Apple plans to announce availability in Canada and Europe in 2007, and in Asia and Australia in 2008. Although the famously secretive Apple hasn’t released its plans yet, it’s likely that it will work through partnerships again, leveraging the iPhone’s prestige to ensure distribution. So far, it has fought hard against efforts in France and Germany to release the phone as an open device, limiting the openness of the device in France to French carriers and winning a court battle in Germany to keep the device locked to T-Mobile.

Given Apple’s insistence on control, is the iPhone really a sign of Web 2.0? Perhaps not—Apple doesn’t recognize that fighting the Internet is rarely a successful strategy—but at the same time, the iPhone experience demonstrates how a company can leverage its existing experience and brand, connect with allies, and make money while combining an old business (telephones) with a new one (handheld access to the Web).

Lessons Learned

Revolutions may bring success, but not every successful business leads a revolution. Established companies that have built infrastructure, reputations, and customer relationships can also make good alliances. They benefit from the growth that newcomers can create, while the newcomers can enjoy much of what the older firms have to offer.

Apple and Jajah offer softer alternatives than their crusading predecessors. Pioneers Napster and Kazaa had left record executives convinced that digital music was the enemy, while Skype’s proclamations of the coming end of established phone networks left the telecom industry wondering what its future might look like. Apple offers the music industry a way to collect on its enormous library of recordings while joining the digital age; Jajah offers telephone companies a share of its revenue while shifting its customers away from regular long-distance service.

Both Jajah and Apple have depended on their users to grow their businesses, though Apple’s key hardware component—the iPod and, later, the iPhone—makes its model a little more complicated. Jajah relies on word-of-mouth to spread the message of free phone calls, whereas Apple relies on word of mouth and the media to spread the message that the iPod and iPhone are cool and “must haves.”

Apple’s ecosystems are much more complicated than Jajah’s, the result of the iPod’s business model, which sprouts new connections to support the iPhone. Nonetheless, all of them rely to some degree on cooperation and take advantage of network effects where possible, or on more typical economies of scale where network effects aren’t available.

The iPhone is still brand new, finding its place in a field in which Apple wasn’t previously established, but its success or failure promises to illustrate how far this kind of collaborative ecosystem building can go and what impact it can have on an evolving field.

Questions to Ask

Your business may not mine gold, produce shiny iPods and iPhones, or handle telephone calls, but you are likely to have old practices that can grow by connecting to new ones—or new ideas that need to build a foundation on older businesses.

Strategic Questions

What opportunities do you have for collaborative or recombinant innovation that could create a breakthrough possibility and opportunity?

Is collaborative innovation relevant to both sides? Is a particular collaboration win-win and positive sum—or is one party contributing/taking away more than the other?

What shared work or know-how will this collaborative innovation stimulate? What additional kinds of mind set shifts, conversations, and processes will this collaboration and the shared knowledge require among those involved?

What assumptions or beliefs are embedded in the process of the way this innovation will take place? Will there be issues with NIH (Not Invented Here) or perceived “cannibalism” of existing products and services or channels?

Is this collaborative innovation likely to generate forward out-of-the-box thinking, or is it likely to increase a focus on past problems and obstacles?

Does this collaboration leave room for new and different ways to work together, especially with a larger group or ecosystem of partners?

Consider how your business and industry currently works. To what degree have you opened up to “collaborative innovation,” multiplying the ways that users inside and outside of your project, team, or organizational unit can easily leverage, aggregate, and spark collective work, knowledge, and systems?

If you took the perspective of a CEO and strategic leader, how and when do you see Web 2.0-enabled collaborative innovation disrupting the current practices, business model, competitive advantages, and economics of your business and industry? What’s the risk of being a leader or laggard? When should this become a board room agenda item?

If you took the perspective of a CIO and program manager, how could you better benchmark, analyze, compare, and quantify the impact of shifts in collaborative innovation in key functional areas (e.g., marketing and sales, product and services development, customer support, inventory management, logistics and operations, recruitment and training, partner and supplier relations, and procurement)? How can this provide a new basis for enterprise and financial valuation?

Tactical Questions

What existing businesses (or business units) are likely to feel threatened by your projects?

What kind of support would you like for your projects from other businesses?

Among your competitors, are there any areas where competition is less keenly felt?

Can you find synergies among the network effects you create and your suppliers?

Do you have a product or service that could complement an existing web service?

How do you see your company diversifying or expanding opportunities?

What are your online-offline opportunities?

How can you maximize your online opportunities?

Do you have a product(s) that could be “recombined”?

How can you streamline processes or distribution?

[32] Hal R. Varian, “An iPod Has Global Value. Ask the (Many) Countries That Make It,” New York Times, June 28, 2007, http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~hal/people/hal/NYTimes/2007-06-28.html.

[33] Steven Levy, “Q&A: Jobs on iPod’s Cultural Impact,” Newsweek, Oct. 16, 2006, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15262121/site/newsweek/print/1/displaymode/1098/.