Chapter 16

THE SCIENTIST

MEET THE SCIENTIST

Consider all of the best qualities of a mouse: intelligent, driven, and capable of solving any maze for the sake of that delicious piece of cheese at the end. The mouse is not worried about the work that might be involved along the way, whether it’s another puzzle to solve or a wheel to run on. In a similar way, Scientists are willing to put in as much work as necessary to accomplish their goal. The end result? If not cheese, definitely a well-informed and impressed audience.

Preparation is a Scientist’s specialty. A formula for preparation might look a little something like this: research, storyboard, design, rehearse, and repeat. Scientists don’t worry about how long this process might take; instead remain focused on doing a thorough job to prepare themselves before they step onstage. They calculate audience needs, they are fully aware of what is expected from them, and they devote themselves to fine-tuning their message and design.

If you scored as a Scientist, you might be a master of thorough preparation in other areas of your life. Maybe you’re the kind of person who likes to read the instruction manual before playing a board game. Perhaps you like watching how-to videos online. In any case, “attention to detail” are three words that don’t scare you. This is one of your best qualities, especially because we believe that the bulk of a great presentation is set up before a speaker even steps onstage.

What happens when a Scientist presents? The results can be mixed because they are often weighed down by the bulk of their own efforts. With so much research, so many data points, and so much detail, Scientists can fumble as they worry about missing important information.

A narrow focus on the data rather than on the impact of a speech can also hurt an audience’s memory of the main points. Sometimes too much is just too much. No one hearing Scientists doubts that they know their stuff. The problem lies in transmitting this knowledge in a clear way to the audience.

If you struggle with getting the audience to leave satisfied and fully informed, your focus needs to shift away from preparation and toward the audience. How can you simplify your message without talking down to them? How can you edit your data, facts, and stats to include only the most relevant information? Sometimes it’s about putting down that clipboard, setting aside that beaker, and focusing on what the audience experiences rather than showcasing how much research you put into the talk.

HOW YOU SCORED

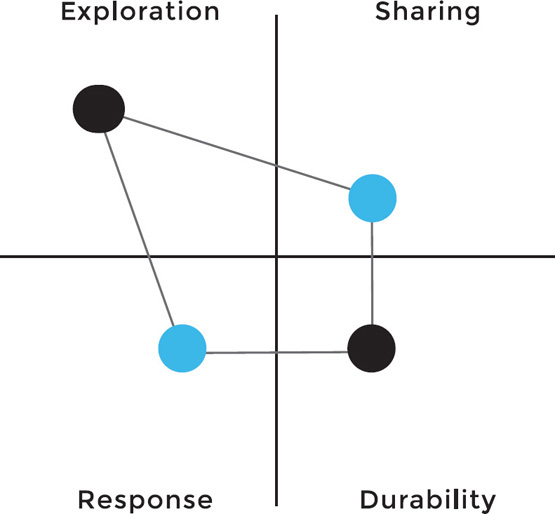

So how did you score the Scientist? These results were calculated using our four-quadrant algorithm in which anything on the outside corner of the specific quadrant is considered high and anything near the main intersection is considered mid-low (Figure 16.1). Here is a simple rundown of your placement in each quadrant and how we arrived at your profile:

Figure 16.1 The Scientist

EXPLORATION

Scientists score in the highest possible area of this quadrant, with a value so high that it almost breaks through the chart itself. More than just prepared- ness, Scientists also have a broad comprehension of what the expectations for their speech might be. They know how high the stakes are, and they also know exactly what the repercussions of either success or failure can be. This knowledge greatly affects the time they put into researching their topic, creating a content storyboard, designing the slide deck, and rehearsing the presentation out loud. As a Scientist, you can see all of the different chess pieces and potential moves on the table. You use Exploration as a way to make the right choices for every move you accomplish.

SHARING

When the stakes are high, the stress is high. Scientists fall in the mid- to low range of this quadrant, perhaps because of an overload of information and the high pressure that they put on themselves. It’s hard to seem natural when you are struggling to remember paragraphs of a speech or strings of information. You don’t lack ability or drive to do well in Sharing, which should be much more about having a conversation with your audience than becoming an auctioneer of facts and stats. When Scientists are able to let go of this, they perform much better.

RESPONSE

You might think of this quadrant as the second half of Sharing, so Scientists fall into the mid- to low range of this category as well. Are you uncomfortable hosting a Q&A? Unsure how to answer difficult questions or wrap up a presentation? Preparing for a strong immediate response is all about ad-libbing with your audience, which memorization can’t help you with. Instead of rehearsing alone in front of the mirror, buy a friend a drink and talk over your main points. Answer his or her questions and become comfortable discussing your topic in a more natural way. Then, when the big day arrives, you’ll already have experience chatting about your subject rather than just delivering it.

DURABILITY

This quadrant might pose some revolutionary ideas to Scientists, who tend to score in the mid- to low range. What if your audience took the information that they learned and applied it in a real-life way? What if they were able to remember your message long after the talk was finished? In order to make a message durable, Scientists need to edit the content of their message from the Exploration stage. They need to learn ways to twist, shape, and mold their message into something much broader and longer-lasting. Not sure how this might work? Check out Chapter 22 about Quadrant 4 later on in the book.

SPOTTING A SCIENTIST IN THE WILD

Meet Lilly, a reporter at a local publication called The Daily Tuba. She’s new to a small team of seasoned reporters. She is also new to the city, which makes her feel intimidated in her starting position.

What sets Lilly apart, however, is her drive. She’s a thorough writer who makes sure that every single one of her facts and sources is vetted before putting a word down on paper. She is also a fast learner, and she is highly motivated to become one of the best reporters at The Daily Tuba.

Every month, the team meets for a session during which the reporters pitch ideas to the editorial staff for long-running pieces or monthly features. The best one or two ideas are adopted, and special real estate is made available for these features online and in the printed paper.

Lilly has an idea to run a feature about adjunct professors in her town. She is convinced that there is something fishy going on with the percentage of tenured professors and the number of recent adjunct additions that come and go through a revolving door. While the story is interesting, the problem is that she wants almost double the normal feature space to accommodate all of the testimonies and other information she’s already uncovered.

To convince the editors that the extra space will be worth it, she’s prepared a presentation to show some of the most shocking stats her research has revealed. She has a set of quotes, images, copies of pay stubs, and student interview footage that she wants to include in her deck to support her case. The problem is that Lilly has compiled too much information, and her editors will suspect that her article will need to be edited in the same way that her presentation needs some pruning.

Lilly needs to put on an editing lens rather than her normal research-driven reporter lens. She needs to look objectively at the content that she has acquired to find the emotionally compelling information. Overwhelming her audience is not going to convince them that she deserves more room in the newspaper. She needs to make her point clear, draw the editors in with compelling information, and then end the presentation with her main point repeated for emphasis.

Lilly is an underdog, but she’s also a Scientist. She already has everything she needs to make a convincing case. For most people, gathering information is the hard part. For Lilly, her challenge will be to edit everything down to what is essential to persuade her editors to give this story a huge feature. Perhaps the only thing that stands between a Scientist and success is a shift in perspective from asking, “How do I prove my point?” to “How can I make my audience feel the same way I do?”

YOUR NATURAL HABITAT

Small crowds, large crowds, and medium-size crowds, oh my! Scientists are usually anxious about any number of people watching their presentation, but they feel a little more comfortable when the group is large enough that they don’t have to answer questions or mingle afterward. Embrace this fear by leaving your audience with materials that don’t require a guide, such as handouts with more information or other valuable takeaway resources. That way your audience will feel satisfied and not abandoned with the information you presented.

BRAWN (STRENGTHS)

Thorough

Dedicated

Prepared

Your search history is miles long before you even type a word into a PowerPoint document, and you know how to cite your sources. Scientists are one of the most thorough and invested personalities when it comes to creating a content storyboard or designing their presentations; no topic is too difficult, no amount of research too small. It’s this can-do attitude that separates you from the crowd and gives you an unbeatable dedication to your message.

“Dedication” is the key word here. While other people may go through the motions of preparation in order to get the project over with, you work hard because, frankly, you enjoy it. You like being able to tinker with content and design until it feels just right, and you appreciate the joy of a well-sourced document that is watertight.

TRAPS (WEAKNESSES)

Anxious

Momentary

Uptight

What happens when the best formula fails? Sometimes the act of preparation does not create the desired results; there are just too many unknown factors. Scientists’ presentations risk coming across as too data heavy to be memorable, and Scientists seem to be too focused on their materials to be relatable. Don’t just work on the tangible facts but rather work to prepare for the theoretical events that could happen during your talk. Random questions, a quiet room, and unengaged audience members are included in this list. In short, prepare for anything that can’t be easily Googled.

Scientists also struggle with being natural and conversational onstage. It’s not easy to be yourself when a group of people, perhaps even a group of scary strangers, are staring at you. However, tactics such as starting with a personal story and peppering your talk with personal details may help ease you through the speech, and they may also help you appear more relaxed.

YOUR NATURAL ALLY

Take a lesson from Captivators (Chapter 5) and find inspiration in their ability to perform well onstage. Watch, listen, and interact with any Captivators you can find.

YOUR PREY

You appeal primarily to other research devotees, such as Curators, Scholars, and Navigators, who will recognize and appreciate your thorough work. These are the personalities who love to see sources cited and can recognize when you’ve spent time rehearsing main points over and over. Give them a reason to launch into a standing ovation at the end of your talk by making a call to action that appeals to the lifelong learners in your midst.

YOUR PREDATORS

Sweet and salty, good cop and bad cop. People love to have a balance of serious and “fluffy” when it comes to a presentation, as with any performance or educational experience. Audience members who search for levity within your presentation and find none may be disappointed, but they are also less likely to remember your main points.

FIVE DOS AND DON’TS

DOS

1. Add a friendly, warm element to your talk by sharing a story that shows your audience why the subject matter excites you.

2. Chances are, you’re putting way too many takeaways into your presentation for anyone to remember. Good Scientists know when they are at risk of overwhelming their audience, and they can edit their points accordingly.

3. After you finish the first draft of your presentation, write down a list of potential audience questions about the content itself. Can you answer these during your talk? If it’s a “maybe,” consider adding a Q&A session to facilitate better audience comprehension.

4. Always make eye contact. Break the room into three sections and take time to focus on one person in each section. Rinse and repeat.

5. When was the last time you devoted preparation time to rehearsing the delivery? More than that, when was the last time you actively asked for feedback on your delivery? Be sure to spend a little more time polishing your onstage performance.

DON’TS

1. Don’t ignore your audience’s needs. What are they getting out of your talk? How can you ensure that they walk away thinking, “I gained a new perspective, and I love it.”

2. Don’t forget that a presentation can be more than just informative. It can be used as a powerful tool for persuasion. How can your message change hearts and minds? How can it improve the lives of those who watch it?

3. Don’t let your slides be the star of your presentation. They may be informative and beautiful, but they will rely on the strength of a great presenter to make them memorable.

4. Don’t include so much content and so many slides that you need to rush to meet your time limit. Timed rehearsals and careful editing can help prevent a speedy style.

5. Don’t let research eat up the bulk of your preparation efforts. Divide your time equally between delivery rehearsal, audience research, and presentation content and design.

THE IDEAL SCIENTIST

There is no such thing as a bad persona. There are only areas to improve on within your range of strengths and weaknesses. With that in mind, what do ideal Scientists look like?

1. They are able to edit the unnecessary within their presentation, trimming it down to be as clear and simple as possible.

2. They refocus their goal away from displaying their hard work to evoking emotion in their audience.

3. They adopt a more conversational tone to make their delivery more natural, including tactics such as storytelling and using nonverbal cues to exude warmth.

Let’s revisit Lilly, our motivated reporter from The Daily Tuba. What happens when she changes her perspective and works on becoming the ideal Scientist?

1. She cuts her presentation in half and limits her sources to a single compelling story, which gives her deck a strategic focus on what matters.

2. She starts the presentation with a personal story about her experience talking to an adjunct professor with a large family who is trying to make ends meet.

3. She invites questions after her presentation to address concerns about the length of her article, which gives her credibility and impresses the team.

When ideal Scientists step back from their own mountain of work and view that same mountain through the audience’s eyes, they are able to make the changes they need to improve as presenters. Sometimes it’s less about asking how and more about asking why. Scientists have an advantage that many presenters don’t in that they are capable and willing to understand both. It’s important that you not let the “how” take over, devouring the content of your talk and distracting you and your audience from what really matters.