— 3 —

A MOVING TARGET

I had a couple of hours after my meeting with Shirley before my next interview—with Scott Beckett, VP of the oil and gas products division. I used the time to review more reports and to clean up my notes. I was glad that I didn’t have to go directly into the meeting with Beckett. He was a division general manager, running the largest and most profitable business unit, and probably the second most powerful person in HGS—after the CEO. I wanted to be really prepared for that interview. And after my meeting with the CFO—well, some of the things I thought I knew for sure weren’t exactly wrong, but somehow they felt less concrete and reliable than they had just a few hours ago.

I was finishing up when Vivek and Bill came into the team room. Vivek greeted me.

“Hi, Justin. How are things going?”

“Pretty well. I had an interesting interview with Shirley Rickert, the CFO. I’m just finishing up the notes. I guess you heard that Gordon wasn’t able to break away from his other engagement this morning.”

Vivek seemed to sense my discomfort. “Oh, I’m sure your interview went well. Can I have a look at your notes?”

“Sure. They aren’t quite done—I want to proof them one more time,” I said, handing Vivek the copy I had just printed, “but you’ll get a pretty clear idea of the interview.”

As Vivek scanned the page, Bill asked, “So, what did you think of Shirley?”

“Very nice, very professional, very competent. I was impressed by her overall, but also a bit surprised.”

“By what?” Bill seemed genuinely interested.

“Well, you probably know that there are six NPV analyses of Plastiwear floating around. Six analyses, some of which generate really different results. I asked Shirley if she knew which of these analyses were accurate. You know what her answer was?”

“What?”

“She didn’t know and it didn’t matter.”

Bill studied me for a second before replying. “Well, that doesn’t surprise me. Shirley’s the kind of CFO who tries to facilitate conversations among various factions in the firm. She usually doesn’t push a particular point of view, especially on controversial issues, but tries to make sure that all points of view are being heard.”

About then, Vivek finished skimming through my draft notes.

“Thanks, Justin. Well written. Sometimes it helps to include the questions you asked in an attachment to your notes. Sounds like you focused in on the NPV work. So, she didn’t have an opinion about which analysis was correct?”

“I was just telling Bill.”

“Yeah,” Bill recapped for Vivek, “Shirley really sees her job as building a consensus, not providing a single ‘right’ answer.”

“Well,” I observed, “one thing I figured out very quickly in the meeting was that present value analysis is anything but a clear and objective way to make decisions in a company.”

Vivek’s observations about present value analysis were more balanced than mine. “It can be a helpful tool. But it can also be abused. You can start with the goal of concluding that a project has a positive present value, and then build a model that generates that conclusion, or you can start with the opposite goal and build a model that reaches a negative conclusion. You don’t have infinite flexibility—if you follow accepted norms for constructing net cash flow projections and choosing discount rates—but you always have at least some flexibility. What is next on your agenda?”

“Lunch. Then a meeting with Scott Beckett.”

“The oil and gas guy?”

“Yes. He hates Plastiwear. He also managed the two teams that generated the negative present value analyses. I need to find out why he’s so down on it.”

“Great. Have you structured the questions you’ll use with him?”

“I’m just starting to work on them right now. I thought I would organize them into three categories—market size, strategic ownership, and timing of the investment. First: What is the magnitude of the dress shirt opportunity in terms of market size? Second: Which of their assets and attributes make HGS well suited to take a position in this market? And third: Is this the right time to move on this opportunity?” I had pulled these questions from a session held during my orientation week.

Vivek seemed pleased. “Great start. I’ve used a similar approach, which will make it easier to compare the results of our interviews. And we can also use the same questions to evaluate alternatives to investing in Plastiwear—for example, opportunities for product extensions in the oil and gas division or other innovations.”

Vivek then turned his attention to Bill, who looked up from reading through my notes.

“Bill, is there anything helpful you can tell Justin about Beckett?”

“He’s no-nonsense,” began Bill. “Really understands the ins and outs of the oil and gas business. Ambitious. He probably comes across a bit gruff, but he is deeply committed to both HGS and to the oil and gas division. His people are very loyal—he always looks out for them. A manager’s manager. I reported to him when I ran the oil and gas plants in Mexico.”

“Thanks for the background.” I wondered why Bill hadn’t volunteered more, sooner, since he knew the guy so well, but already the two of them were on their feet. “Good. Well, Bill and I are off to interview some more marketing people, in both the oil and gas and the packaging divisions. You’ll have our notes later today. By the way, we’ve already e-mailed our notes from the interviews this morning and posted them in the virtual team room,” Vivek remarked off-handedly as he and Bill left the team room.

So far, I had not seen Vivek eat and, given the volume and pace of work he was generating, I had just about concluded that he never slept either. Just what I needed—on my first assignment, I get paired with a consulting “iron man.”

That said, the fact that Vivek had validated my approach to organizing questions for Beckett renewed my confidence—a confidence that had taken a hit from my interview with the CFO. In addition, Bill’s comments about Shirley suggested that what she told me in the interview was consistent with his experience. That was good news.

Now I had to put the CFO behind me and concentrate on preparing for Beckett. After a couple of hours of additional work over a cold sandwich, I felt like I had a clear agenda for my next interview.

________________

I arrived at Beckett’s office a few minutes early. There was no one there to greet me, only an empty chair at what I assumed was his secretary’s desk. After a few minutes I peered into the open door of his office. It couldn’t have been more different from Shirley’s. There was little in the way of comfort. The chairs were solid and heavy, made of metal with black vinyl upholstery—the kind that sticks to your skin on hot and humid days—and the metal desk had seen better days. A whiteboard on wheels stood in the corner, with a few scribbles on it. The walls held plaques for quality and performance awards, but no personal mementos were visible—not even pictures of a spouse or children.

I was tempted to pace the hallway, but redirected my nervous energy to scanning some articles in a trade journal I picked up from a pile of newsletters and periodicals in the common area. Despite having done a couple of oil and gas cases in my MBA program, I soon got the sense that there was a lot I didn’t really know about this industry.

After another ten minutes, I thought about calling to check if I was in the right place. Just as I began to dial Darla Hood—Carl Switzer’s secretary, who had set up our interviews—Beckett arrived, with his secretary trailing a step or two behind. They were deep in conversation—or more precisely, Beckett was talking and she was nodding and taking notes.

“Martin can get you the numbers, and you can forward them directly to Anne. I don’t need to see them. Just make sure we keep a copy for Monday’s meeting.”

Beckett motioned to me to follow him into the office and gestured toward a chair while he wrapped up his instructions to his assistant. He turned to me and started right in.

“So, if it was your money, would you invest in Plastiwear?”

I was a bit taken aback, but responded, “I’d certainly take a good look at the opportunity. I know I’d rather wear a Plastiwear shirt at an attractive price than pay the same for something less comfortable that didn’t last as long.”

“Oh, yeah, wearing the shirt.” He paused and for the first time looked directly at me. “As a consumer, you have your preferences.”

While Beckett had looked pretty put together in our first meeting yesterday—a tailored suit, nice shirt, a perfect tie—today he was more relaxed, like he had gotten his fashion tips from Bill Dixon. Only a step or two above scruffy, his gray pants were a bit baggy, his long-sleeved white shirt well worn, a blue striped tie hanging five inches from his belt. Yesterday, he looked like, oh, I don’t know—a CEO in training. Today, he looked like an engineer.

“But,” he continued dryly, “we have to consider the situation as manufacturers—not consumers—and from that perspective, this is a very tough play.”

“You suggested this in our earlier meeting,” I began, but he continued, taking little notice of my comment.

“When evaluating a new product like Plastiwear, I always look at the industry to see whether there is an opportunity for HGS. Some industries are more attractive than others, and sometimes it’s hard to decide if—net net—an industry is a good one or not, but the men’s dress shirt industry—no question, from the very beginning, I’ve been convinced it’s very unattractive.”

I fumbled for words to steer the conversation toward my question list, but wasn’t quick enough. Beckett moved to the whiteboard near the window, picked up a marker, and continued.

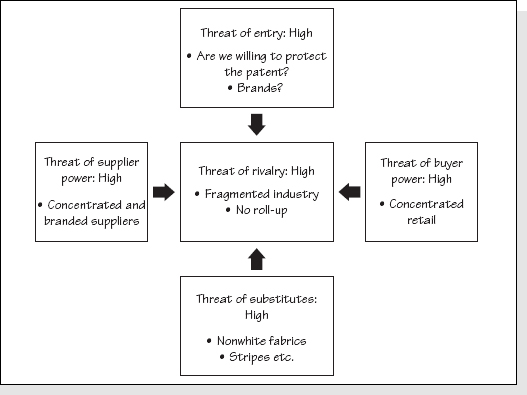

“We all use five forces for this type of analysis. Start with rivals.” To emphasize this point he wrote the word rivals on the whiteboard. Suddenly a student, I wrote rivals on my notepad as well.

“Rivalry for an HGS entry into men’s shirts would be a real problem. It’s a fragmented industry with over a hundred players, no one of them dominating more than 3 percent of the market. It’s not easy to compete in these types of industries, and the first thing that might come to mind is a roll-up strategy—consolidate the industry by exploiting scale in, say, shirt manufacturing. Maybe we could make a really bold move into this space, buy a few firms, integrate them with our own shirt technology, so that we have some clout. Not practical.”

He continued in the same clipped, decisive tone. “Roll-ups work when there are ways to standardize and gain scale. Fashion content makes this industry very resistant to standardization. Even white dress shirts come in hundreds of different style and size combinations, with different fabrics and weaves and other variables.”

Agreed. Just browsing the Internet, I was amazed at the complexity of what I had assumed was a simple product. I was going to share my thoughts, but he didn’t give me a chance.

“And while there might be some upstream economies of scale in manufacturing the Plastiwear fiber and fabric, there are none in cutting and sewing shirts. That’s why so much of this work is sent overseas. You’ve got one person cutting, maybe, a hundred shirts at once, but assembly can’t keep the same pace. Even if you could get some automation—and I don’t think that is technically possible—why would you want to make big bets on a particular product or style?”

“What do you mean?” There. My first question.

He looked at me, noticing my attire as he responded. “Obviously, with changes in tastes and fashion, firms that make too large a bet on a particular style, size, or color can easily end up with their cash tied up in unsold inventory. This happens even with common dress shirts—different collars, fabrics, and so forth move in and out of style. One reason the apparel industry remains fragmented, besides the fact that there aren’t big scale economies, is that many firms are hesitant to make large investments in any particular cut or style. Unlike consumer electronics, one standard platform won’t dominate all our wardrobes anytime soon.”

Beckett continued without skipping a beat. “So where is the power to extract profits in this industry? It’s a tough play because both the customers and the suppliers have the power.” Now he turned to the whiteboard to make his point. “You can’t dictate to the customers—the large retailers. They decide what they’ll stock, how much they’ll pay, and who they’ll work with. You also have no leverage with suppliers. The fiber and fabric industry is relatively concentrated, and a small number of players are dictating pricing, supply terms, and delivery schedules. With suppliers who can hold up your production and customers who can take or leave your product, I feel sorry for the poor middleman trying to make a shirt.”

At this point, I felt I really needed to join the conversation, but the phone rang, and Beckett picked it up. He conducted some business on another matter without waving me out of the room, so I waited and thought about my next step. I decided to put aside my earlier line of questioning and instead go with his application of the five forces model. Fortunately, I had applied this common model frequently during my MBA program.

As Beckett hung up the phone and prepared to continue his lecture, I jumped in. “At least with a proprietary fabric, you would have a barrier to entry and there would be little threat from new entrants into that segment of the shirt market where Plastiwear could dominate.”

“You’d think so, wouldn’t you?” Beckett nodded and looked down at his marker. “But you’d be wrong. Patents aren’t defensible without deep pockets and vigilant legal teams. I’m not sure we would have the guts needed to stick this strategy out. But for argument’s sake, let’s assume we can run without direct competition with an iron-clad patent. Many players in plastics, wovens, apparel, and fiber operations are constantly introducing new fabrics and trying new things. We would just be one in the crowd.”

“What about branding the shirt, gaining an advantage that way?”

“Did you honestly look at the brand of the fabric when you bought that shirt?” he asked, already sure of my answer.

Shaking my head, I acknowledged his point. “Price and availability had a lot to do with my purchase of this particular shirt. It’s not that I ignored the brand on the label, but if this brand of shirt had been too expensive, I wouldn’t have bought it. And I definitely don’t know the maker of the fabric.” I didn’t bother to tell him how fresh the purchase experience was in this case.

“Look. I’m not saying no one is willing to pay for a dress shirt made from a branded fabric. But is that market really large enough to justify the investment we would have to make? I don’t think so.” He continued to the rest of the five forces. “There are plenty of substitutes for white shirts, and I don’t think we’ll suddenly storm that market when people go to work in all sorts of things these days—including plenty of business casual. Here’s a crazy idea—maybe a blue shirt, or a striped shirt—could be a substitute for our simple white shirt.” At this point, he seemed a bit wound up, but he added some more details to the five forces model on the board silently. His summary: “High rivalry, no barriers to entry, lots of substitutes, powerful buyers, and powerful suppliers. Yeah—sign me up for that industry.” The sarcasm dripped off his words.

Beckett’s five forces analysis of the white shirt industry

He continued, “Shirt manufacturing is a dog industry, and we would lose millions if we tried it. Listen, to me this is a classic nonstarter. I’m glad you guys are here, to cut through all the bull crap floating around about Plastiwear so that we can get on with growing our two key businesses.” He glanced at his watch and put down his marker. “If you discover anything interesting you’d like to share, contact my assistant and perhaps we can schedule another time together—maybe spend some time talking about some real high-potential strategic investments. Forget Plastiwear.”

“Well, thank you very much, Mr. Beckett. This has been very informative.” On my pad were blanks next to my three questions: market size, strategic ownership, and timing of the investment. Beckett clearly thought that if an industry was unattractive, the size of the opportunity, its fit with HGS, and its possible timing weren’t even worth exploring.

And just as quickly as my interview had begun, it ended, and I found myself back in the hallway.

________________

My meeting with Beckett was enlightening, to say the least. Obviously, he had very strong opinions, and he wasn’t shy about sharing them. But I couldn’t let that cloud my judgment about his analysis. He did make a compelling case against HGS entering shirts. High rivalry, low barriers to entry that were not easy to fortify, high buyer power, high supplier power, and lots of close substitutes—this was an unattractive industry, no matter how you cut it. If HGS entered and tried to scale up production, protect its patent, and create a brand, I could see how the firm would quickly lose the billion dollars that Beckett’s teams projected it would.

That conclusion was disappointing. After all, my own experience buying a white shirt showed me that while I could get a pretty good shirt for around $85, if I wanted a really good shirt—high thread count, high-end cotton, and so forth—I would have to special-order it, and it would cost around $400! If you could get a high-quality shirt at $60, or even $100—and that was what Plastiwear was promising—boy, that looked attractive to me.

But Beckett’s analysis seemed airtight. And even though it was negative, it felt good to have such a concrete conclusion to share with the team. And that was what I was going to report in our first team update. Ken had set a 7:00 p.m. meeting time. He would join us on the phone, as would Livia. The rest of the team—including Bill and Gordon—would be there in person. So far, Vivek, Bill, and I were the only ones who had put in any time on this project, so I assumed this meeting was our chance to brief the rest of the team on our conclusions.

I finished my interview with Beckett around 5:00 p.m. That gave me two hours to type up my notes, e-mail them to the rest of the team, and prepare for the team meeting. I also had to respond to the revised work plan Vivek had somehow found time to draft and circulate. But most of all, I had to prepare an airtight case against Plastiwear.

While I had been doing my interviews, Vivek and Bill had been meeting with marketing managers at corporate headquarters and in the two big business units, trying to understand their perspectives on the Plastiwear opportunity. Given Vivek’s relative experience, it didn’t surprise me that, when the meeting began, Ken and Livia turned to him.

Ken spoke first. His disembodied voice on the telephone reminded me of Charlie on Charlie’s Angels.

“First, Bill, are you there?”

“Yes, I’m here, Ken.”

“Well, Bill, it’s nice to meet you, even if it’s only over the phone. We consider ourselves fortunate to have you with us on this project. Carl tells me you’ve already pitched in, helping us in this very tight schedule. We appreciate your help.”

“I’ll be glad to help however I can.”

“Great. Why don’t we start with the marketing interviews? Vivek, we’ve all had a chance to read your notes. Anything you want to add?”

I suddenly realized that I had not read these reports.

“Yes, thanks, Ken.” I think Vivek was a little surprised that he was going first, because he was right in the middle of a bite of food when Ken called on him. We had ordered dinner delivered to the team room—our table now stacked high with Chinese food, soft drinks, HGS reports, and printouts from various financial and data collection services.

Regaining his composure, Vivek continued, “I just wanted to emphasize how much the marketing people hate the name ‘Plastiwear.’ I didn’t put this in my notes, but one manager said it sounded like a product right out of The Jetsons—you know, the cartoon about the family in the future. And not in a good way.”

Several of us chuckled at this reference, although I didn’t think Vivek would have ever seen The Jetsons growing up in India. I had heard about it, but I’d never actually seen the cartoon.

Gordon agreed. “I also thought it was an unfortunate name. ‘Plastiwear’—sounds like something out of an old science-fiction movie. Either that or a line of adult diapers. You can hear the tagline now—‘Plastiwear Diapers—When It Counts the Most.’” While this banter went on, I concentrated on the details of my argument against a Plastiwear investment, a bit impatient about the team spending so much time discussing the name, even in jest.

“Well,” replied Livia, who seemed to share my desire to move on, “HGS is a specialty chemical firm, not a marketing company. If we end up recommending that they pursue this opportunity, we can also recommend getting marketing experts involved to come up with a solid branding strategy.”

Ken picked up the thread. “Vivek, aside from the unfortunate name, anything else that will add to the synthesis and suggestions in your notes?”

“No. Overall, the marketing managers we interviewed had remarkably little to say about Plastiwear. They are very much an industrial marketing group and focus almost all their efforts on building the industrial brand. They have no experience and, as far as I can tell, no expertise in retail marketing. If HGS decided to brand Plastiwear shirts, they would have to develop an entirely new skill base—or at least get access to that base from another source, as you’ve suggested, Livia.” Everyone nodded in agreement.

Livia followed up on Vivek’s comments. “So, part of this engagement may involve helping HGS either develop or hire some retail marketing expertise or helping them find partners with the appropriate expertise. If we recommend in favor of a retail strategy, that is.”

Ken’s reply was cautious. “That is always a possibility and might be a way forward. Let’s do our homework before we start to think too far into the future or close off any options. What we need now is as objective a read as possible about this opportunity. It seems to me that HGS is framing this as a retail play, and Vivek—it sounds like you didn’t have a chance to discuss how some of the B-to-B marketing experience they have at HGS might be relevant to us.”

I’m sure that Vivek saw this comment as a mild rebuke. I know I would have.

Ken continued, “So, Vivek, maybe you can think about how we might leverage whatever marketing skills they do have. Also, could you continue to explore which players on the marketing side have the power, or the incentive, to block or accelerate progress on a Plastiwear launch?”

“No problem, Ken. I’ll get on those issues right away.” I guessed that Vivek would probably be working all night rethinking his approach to marketing and that by tomorrow he would have an entirely new set of ideas. Vivek—consulting “iron man”!

Ken continued, “Bill, did you want to add anything to Vivek’s observations?”

“No, I think he summarized the state of marketing in HGS accurately. If we were to try to get into retail, no doubt, we’d have to develop or somehow access some entirely new skills.”

Ken then moved the meeting on to me. “Justin, your notes suggest that the VP of oil and gas products is quite pessimistic about Plastiwear and HGS playing in the shirt space.”

“Yes, Beckett is extremely pessimistic,” I replied.

“Do you have anything to add, over and above your notes?”

“Only to emphasize that I thought his approach—or rather, his team’s approach to this problem—was very careful and very thorough.”

“And you think the industry attractiveness analysis he used is a good basis for making strategic choices?” asked Livia.

Livia had asked a question I hadn’t thought of. In my MBA program, I had learned all about the five forces framework. I had practiced applying it maybe a hundred times, on different cases. But I had never really thought about whether it was a good way to make strategic decisions. I took it for granted—evaluate the attractiveness of an industry and enter only those that were attractive. Oh, there was something in my book about the limits of five forces analysis, but …

Suddenly, my response was less confident than I would have liked. “Yes. That’s what I learned. Five forces analysis was the starting point for nearly every case we did.”

Ken’s reply was a bit impatient. “We usually start with that kind of analysis as well. But it’s just a preliminary step.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well,” continued Ken—suddenly not just the senior consultant on the project, but now channeling a demanding professor—“there are a couple of clear limitations of this five forces approach. First of all, how would you characterize the perfect—the most attractive—industry possible, according to the five forces model? For example, how much rivalry would there be?”

“Very little.”

“Like, none, right?”

“OK.”

“How close would substitutes be in this industry?”

“Not close at all.”

“And the other threats?”

“Well, there wouldn’t be a threat of entry, no powerful buyers or suppliers.”

“Exactly. Now, what kind of industry has the attributes you just listed—no rivalry, no substitutes, no entry, no powerful suppliers or buyers?”

I thought about his question for a second before it became obvious. “That’s a monopoly.”

“So, what does that mean for using five forces to make strategic choices?”

Again, I had to think quickly, but muddled through. “I guess it means that firms should enter industries that are already monopolies or could be turned into something close to a monopoly.”

“And how often is that likely to be a viable option for a firm?”

Yet another question I had not thought of in my MBA program. “I guess, not very often.”

“Come on, Justin,” continued Ken, “given globalization, the number of industries where a firm can expect to either create or exploit monopoly power is very small. I’m not saying it’s impossible. And when we have a client that is operating in a monopoly or oligopoly, sure, five forces logic helps to focus on factors that might make its situation more competitive. But most firms at least have active rivals and viable substitutes.”

“I can see that,” I replied. “It doesn’t seem likely HGS would have a lot of opportunities in any of its businesses, based on five forces logic—given the highly competitive nature of its businesses, I mean.”

“That’s right. So, what that means is that using five forces to evaluate the attractiveness of an industry doesn’t tell us very much about strategic choice. In fact, except in highly unusual circumstances, this type of analysis would recommend not entering most industries, right?”

“Because most of the industries that firms can enter will actually not be all that attractive, at least according to five forces logic,” I replied.

“Now you’re catching on, Justin. And here’s another problem. How easy is it to enter a so-called attractive industry?”

“I’ll tell you from my experience, you only want to be in those that are hard to get into. Like that tennis club Ken and Carl belong to,” Gordon offered with a wink.

“So,” Ken continued, “the cost of entering so-called ‘attractive industries’ isn’t all that attractive.”

Ken chuckled, but I wanted to stay on track. I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. “So,” I persisted, “are you saying that five forces analysis is a waste of time?”

“No.” Now Gordon was serious. “We almost always start a strategic engagement with five forces and other basic analyses to help identify the competitive and structural challenges in an industry. This list of competitive challenges usually suggests some strategic opportunities that a firm might be able to exploit, or clarifies the sources of some of its problems.”

I looked around the table, and Vivek was shaking his head in agreement, while Bill sat quietly, watching with interest as the conversation unfolded in front of him.

Now it was Livia’s turn to chime in. “Justin. This is Livia. The five forces framework does a great job helping to identify the competitive threats in an industry. Whatever strategies we develop for Plastiwear will need to address one or more of these threats directly. But using this tool to estimate the overall attractiveness of an industry is usually not that helpful.”

Livia continued on a different tack. “Justin, do you know anything about sailing?”

“I’ve been a couple of times. Why?”

“When I was a child, I just assumed that in order for a sailboat to go, say, east, the wind had to be blowing from the west to the east. I was amazed to learn that, no matter which way the wind blew, a sailboat could always get to where it wanted to go—if it had a skilled sailor at the helm. To me, the five forces are kind of like the wind, the direction that competition within an industry is moving. Strategy is about positioning the firm relative to the prevailing winds in a way to make sure that the firm gets to where it wants to go, no matter what direction the wind is blowing.”

“So,” Ken said, picking up on Livia’s analogy, “it’s good to know where the wind is coming from, but our job is to help firms use the wind to reach their profit and other goals. This is the case even if it is blowing directly against a firm, even if all five forces align against being in an industry and make it incredibly unattractive.”

“In fact,” added Gordon, “some of the most successful firms in the world are successful precisely because they have figured how to use very unfavorable industry winds—high rivalry, high threat of entry, and so forth—to their advantage. Look at Walmart, Southwest Airlines, Nucor Steel, Toyota, Starbucks. These firms have played in some pretty unattractive industries—at least according to a five forces analysis—and still they have been successful.”

“In other words,” concluded Ken, “while Beckett’s five forces analysis of Plastiwear is interesting, it is certainly not definitive. Our job is to identify appropriate ways for our client to compete using Plastiwear, despite these challenges.”

“Of course,” Livia said, almost to herself, “Beckett might turn out to be right. Men’s white shirts may be a nonstarter, no matter what analysis we do.”

As the conversation turned to other matters, I considered the two things I had learned so far working at HGS. First, I had learned that net present value analysis tells you nothing about the quality of a firm’s proposed strategic activities. Second, I had learned that the attractiveness of an industry, by itself, cannot be used to make good strategic choices. As the team continued with a discussion of the work plan, priorities, and hypotheses, I found it hard to concentrate. I was now in the uncomfortable position of having much of what I thought I knew about strategic analysis—present value and five forces—stripped away from me, and in public as well. What would be my next step? With these gaping holes in my strategy toolkit, how was I going to crack this case?

As our meeting wrapped up, Ken asked each of us if we had any parting comments. When it came my turn, I had nothing to add. Frankly, I was eager to wrap up the call, but Ken wanted to talk more. To me.

“Thanks, everyone. I think we’re clear on next steps, but let’s stay in close contact on progress toward deliverables. Post and circulate things as you’ve been doing, but ping me in real time if there is any breaking news. Nice work, Livia, Vivek, Gordon. And thanks again, Bill. Hey, Justin, let’s chat this evening, say about 9:00. OK? I’ll give you a call on your cell. Shouldn’t take long.”

“Great,” I managed to reply as the meeting concluded.

________________

“Let’s chat this evening. I’ll give you a call.” Those words said everything and nothing, no matter how many times I replayed them in my head. I wondered if it would make sense for me to resign now and take one of the Wall Street offers I had turned down. Better than getting fired by Ken tonight! I knew most consultants didn’t stay long, but I hadn’t intended to set a record for shortest tenure ever.

I tried to concentrate on the project in the hours after the team meeting, but the same thoughts kept coming to my mind: “Let’s chat … shouldn’t take long.” What was Ken going to say—“Well, Justin, obviously, you have failed the firm, failed the client, failed your family—and worst of all, Justin, you’ve failed yourself. So, you’re fired.” That would be a short conversation, for sure. Almost as short as my consulting career.

Waiting for this call was worse than waiting for a dental appointment. At least with the dentist, you’re better off after the appointment than before. Later tonight, I wouldn’t have a job. Nine o’clock was only an hour away, but it was the longest hour of my life. Every tick of the clock lasted a minute and every minute lasted an hour. Finally, at three minutes after nine, my phone rang.

My heart jumped. But I told myself to let it ring a couple of times—no reason to appear too anxious. Whatever happens, I told myself, keep cool and remain calm.

“Hello, Justin Campbell.”

“Hi, Justin. It’s Ken. How are things going over there?”

“Well. We just had a couple of reports on the competitive situation in the fabric industry sent over. They are more up to date than what HGS has been working with, although things haven’t changed dramatically in three years.”

“Good. Those might prove helpful. Listen, Justin, I thought it might be a good idea to talk about how you think things are going. I know we all got thrown a curve ball when the time schedule on this HGS project got shortened to just nine days, especially when Gordon couldn’t break out of his client commitments today. That’s put more pressure on the team than normal.” Ken sounded matter of fact. “Sometimes it’s like that, though.”

I quickly decided to fess up to my failures. If I pointed out my own weaknesses, maybe Ken would see that I understand my own problems, take mercy on me, and give me another chance. “Well, I do feel like I got off to a rough start.”

“What do you mean, Justin?”

“Well, it started when I used that example from my MBA class—on multiple conflicting assumptions about opportunities.”

Ken paused, then seemed to connect with what I was saying. “That was a bit naive, but it wasn’t a big deal. Sometimes you new MBAs seem to think that doing strategy work is just trying to figure out which case in your program is most like the client. Real-world strategy isn’t about cracking the case.”

I continued in confessional mode. “Then there was that five forces fiasco.”

“The fiasco didn’t have to do with your report of the analysis you heard from Beckett, which the team needed to be aware of. In fact, your notes were accurate as far as they went. The issue was that you bought his analysis hook, line, and sinker. You didn’t look at his analysis skeptically.”

“What fooled me was that he seemed to do a good job on the five forces analysis.”

“Two things to keep in mind whenever you see someone apply one of these analytical tools. First, whether it’s the five forces framework or present value analysis or whatever, they are just tools. They’re like, say, a hammer. You can use a hammer exactly the way it’s designed to be used, but instead of building something beautiful or durable, you can build a pile of junk. It’s not the tool, it’s how the tool is used; it’s the skills, interests, and motives of the person using the tool that determine whether the outcome of an analysis is reasonable. That leads to the second thing to remember.”

“What’s that?”

“When managers present a point of view, assume their point of view reflects some combination of how things actually are and how they want things to be. In your report, you noted, for example, that Beckett said he always opposed the Plastiwear initiative.”

“That’s what he said.”

“As he made clear in our first meeting. Now, one reason he may be opposed to the Plastiwear deal is that he really thinks it is a bad idea—he doesn’t buy the economics or he thinks it will hurt the firm. But he must also be considering how this strategic initiative will affect him, his people, and his career. How old is Beckett?”

“Mid-fifties, I think.” I paused to check on my guess. “He’s fifty-four.”

“And how old is Carl, the CEO?”

“He’s sixty.”

“So, Carl is about five years away from retirement—assuming this unfriendly takeover doesn’t happen and unseat him. Beckett’s the general manager of the largest, and most profitable, division in HGS. Don’t you think his position, experience, and age make him a top contender for CEO when Carl retires?”

“Sounds reasonable.”

“Now, if you were Beckett, wouldn’t you have a strong incentive to make sure that your division continued to be the largest and most profitable? What is it going to take to continue to grow the oil and gas division?”

“Higher sales, attractive products, maybe some new technologies; I would guess some new manufacturing sites.”

“And what does all this take?”

“What do you mean?”

“What will Beckett need to achieve growth?”

“Managerial attention, I guess.”

“And capital.”

I thought Ken sounded a bit frustrated, so I echoed quickly, “That’s right, capital.”

“Now if HGS commits to a big investment in Plastiwear, isn’t that going to have an impact on the capital available to Beckett and his division?”

“I was taught that if a business unit had a project that could generate positive present value in cash flows, it should be funded.”

“Justin, it’s time to move beyond MBA-land.” Now Ken’s frustration was unmistakable. “In the real world, there is a finite amount of capital to spend every year. Demand for this capital is almost always greater than its supply. If HGS makes a big financial commitment elsewhere, then Beckett might not get the capital he thinks he needs to grow his business. He needs to achieve continuous financial improvement in the oil and gas business to keep his current, and possible future, power. ”

“So, are you saying that Beckett’s analysis was just a way to advance his personal interests?”

“No, nothing that simplistic, but his personal interests color the type and amount of analysis he does. For example, after doing a quick five forces on one industry—men’s white shirts—he sees that this industry is unattractive, and so concludes that the firm shouldn’t exploit Plastiwear. Since the first result of his thinking leads to conclusions that are consistent with his preferences, he doesn’t push any further—doesn’t examine how the threats he’s identified in the industry could actually be turned to HGS’s advantage, for example. Besides that, he already has a full-time job running his division. He doesn’t have a lot of time to do in-depth analyses of Plastiwear applications.”

“So, he’s predisposed to find a particular answer, and once he finds it, he stops looking.”

“Exactly. This is where we, as outsiders, can add value. Our job is to realize that people like Beckett may have stopped thinking about these issues too soon and to push them to think harder about alternatives. I can’t count the number of times I’ve had to work with managers who did analyses that reaffirmed what they already believed, and had to motivate them to start thinking again.”

“Was that what I should have done? Ask him hard questions about his analysis, to get him thinking again?”

“Not necessarily. Mostly, at this stage of the project, we’re just collecting information—getting everyone’s point of view out on the table. If there are some obvious weaknesses in his approach, then yes, it makes sense to raise questions and push back. We will do this, but it usually isn’t in the first interview. No, Justin, the problem wasn’t that you didn’t force Beckett to start thinking again.”

“So, what was my mistake?”

“Your mistake was that you didn’t force yourself to start thinking again. You drank his Kool-Aid instead of remaining objective. For example, Becktt’s five forces analysis focused on the shirt industry, right?”

“Yes.”

“As did his present value analysis—it also focused on returns to HGS if they went into the shirt industry. Right?”

“Yes. So far, most of the analyses I’ve seen in HGS have focused on men’s dress shirts.”

“Well, Justin, suppose that instead of going into shirts, HGS used Plastiwear to go into the fibers and fabric industry—selling fibers and fabrics to other firms who then make dress shirts or other products. Becktt didn’t do a five forces analysis or conduct a present value analysis on that industry, maybe because he got the answer he wanted from analyzing shirt manufacturing. Maybe there is an opportunity in shirts, maybe it’s in the fiber and fabric industry, maybe it’s in just doing research and development into fabrics, maybe there is no opportunity here at all. We’ve barely scratched the surface of thinking about the possibilities. But once you decide which industry you are going to analyze, well, that largely determines the outcome of the five forces analysis. You have the answer when you ask the question. We want to avoid closing down our thinking prematurely.”

“Can we use five forces to identify the right industry to study?”

“No,” responded Ken. “The five forces framework takes the industry to be analyzed as a given. If you analyze the wrong industry, it really doesn’t matter how good the analysis is. Bottom line is we have to explore multiple options along the steps in the value chains that may be opportunities for HGS—especially when we’re evaluating a new technology like Plastiwear. Plus, if we close off options too soon, that can create dysfunctional dynamics within our team.”

“What do you mean?”

“When you buy into unfounded assumptions or jump to premature conclusions—about what the relevant industry or industries are, about what the right analysis is—you can’t provide the objectivity the client needs and deserves. If others on our team do this as well, then conflicts among managers in the client firm are mirrored by conflicts on the strategy team. At that point, unless we’re intentionally role-playing, we aren’t adding the value we should.

“I hope this gives you some new things to consider,” Ken continued, “but I don’t mean for you to be too critical of management. That’s not a helpful attitude either.”

“I got it. Healthy skepticism to remain objective.”

“Just one more question for you tonight, Justin. Why do you suppose it was so easy for you to buy into Beckett’s analysis?”

“Well, I thought it was rigorous.”

“Justin,” Ken said, now sounding a bit annoyed. “It was rigorous. Just incomplete, focused on only one of several possible industries, and very likely self-serving. My question to you is—why didn’t you see these obvious problems? Why did you drink the Kool-Aid so fast?”

“I don’t really know.” I reacted honestly, clutching tightly to my last shred of dignity.

“Next time we talk, Justin, you need to know the answer to this question. It’s the only way we can make sure you don’t get caught up in this same way again. I’d like you to give me a call as you begin to understand what’s going on—not just with the client, but inside your head as well. Good night, Justin.”

“’Night, Ken.”

He hung up.

________________

Well, at least I wasn’t fired. And Ken had given me some great insights about strategy and the project here at HGS. But his last question was a hard one. Once the strategy team had described the weaknesses in Beckett’s analysis, they were incredibly obvious. Industry attractiveness, by itself, usually doesn’t drive strategic choices, since monopolies are so rare and the cost of entering “attractive” industries is generally very high. More important, sometimes a firm can use strategies to turn threats into opportunities, making an unattractive industry attractive—at least to that firm. Even more fundamentally, these kinds of analyses don’t tell you which industry to analyze. No matter how rigorously you analyze the wrong industry, you still get the wrong answer—or maybe the right answer to the wrong question. And sometimes industry analysis—like any management tool, I guess—can be used to reaffirm a manager’s preexisting preferences rather than to objectively analyze a strategic opportunity.

It’s not that five forces analysis is wrong—it just has to be applied appropriately.

But, why hadn’t I seen these weaknesses? Had I ignored them during my MBA program as well? Was I just not smart enough to see them? Was I too tired to focus? Those questions echoed in my head well into the night.

1. Do you agree with Beckett that “shirt manufacturing is a dog industry, a classic nonstarter”? Why or why not?

2. Justin discovers some important limitations of the five forces model. What are those limitations, and under what conditions does it make sense to use this model?

3. How can the strategy team distinguish between objective information about Plastiwear and information that is colored by the preferences and biases of a particular manager?

4. What other questions should Justin have asked Beckett?

5. If real-world strategy isn’t about “cracking the case,” what is it about?

6. If you were Justin, what would you say to Ken in your next phone call?