6

Real Economy First

The chief value of money lies in the fact that one lives in

a world in which it is overestimated. —H. L. MENCKEN

FOR DECADES, THE U.S. FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY has played an important role in allocating capital to great businesses and ideas. Analogies have been made that financial services is akin to the circulatory system, circulating money to different industries and companies. In the process, financial firms assist in creating great wealth, producing world-class companies all over the world today.

But because money is used in every industry, financial services, unlike other industries, affect the entire ecosystem. This special trait therefore puts the financial industry into a separate category from all other industries. As such, a watchful eye must oversee its activities and abilities so that the financial industry doesn’t overstep its boundaries given its unique power. Returning to the circulatory analogy, cash, like blood, is integral to the economic system. But if a patient receives too much blood in a blood transfusion, the patient dies. In other words, the financial services industry, if too powerful, can negatively impact other industries in the economy. In 2008, the world discovered that is exactly what happened.

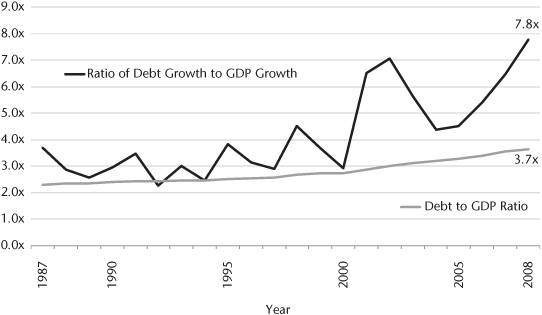

FIGURE 2 The Bubble: A Portrait of Inefficiency and Waste

Source: World Bank; Federal Reserve; Westwood Capital

Masters of the Universe

Simon Johnson, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, wrote in his article “The Quiet Coup” (Atlantic Monthly, May 2009) that Wall Street elites had captured Washington DC. At the time, most Americans were just beginning to make sense of what had happened to the nation. Simon’s accusations—the U.S. government had become a banana republic thanks to financial elites who overpowered democracy—came to some as a surprise. Shortly thereafter, Matt Taibbi, editor of Rolling Stone, wrote more colorfully that Goldman Sachs was a vampire squid sucking up humanity. In other words, he was describing how Goldman Sachs had used its unprecedented reach and power to defraud millions of people around the world and get away with it. Since then, much has transpired that has reinforced their views and those of many others who have written countless books and articles about the financial crisis.

Contrary to what the news media reported, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 was not nearly as sweeping and radical as the legislation that came out of the Pecora Hearings after the Crash of 1929. Back then, the U.S. government enacted the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated commercial banks from investment banks so that speculators could not use money from depositors for speculative purposes. Lawmakers also created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to protect bank depositors and the SEC to monitor fraud. But in 1999, during the Clinton administration, the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act was repealed. Consequently, large commercial banks such as Citigroup undertook speculative activities that ultimately required billions of dollars worth of taxpayer bailouts to save them from bankruptcy. The Financial Reform Bill that was signed into law by President Obama did not reinstate the Glass-Steagall provision. It also didn’t put into place any of the critical measures that could prevent another large-scale crisis from taking place again, such as forcing the large banks to split up into smaller banks to avoid the moral hazard known as “too big to fail” (TBTF). Advocates of real financial reform, who claim that banks outspent them in lobbying dollars by a ratio of 100 to 1, maintain that the “reform” was mere window dressing to appease the financially illiterate public. The legislation did not change the rules that precipitated the crisis, but only instituted token changes that would not deprive financial institutions of the freedom to operate as they wish. The environment we have created can be summed up in one word: financialization.

What is financialization? Here are just two of the various definitions offered by academics:

• “a pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production” (Greta Krippner of the University of California, Los Angeles)

• “a process whereby financial services, broadly construed, take over the dominant economic, cultural, and political role in a national economy” (Kevin Phillips in his 2006 book, American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century)1

Whichever definition one uses, financialization describes a classic case of the tail wagging the dog. In theory, financiers are supposed to help the real economy operate more efficiently by finding the best uses of capital. But in today’s reality, the real economy has been hampered by financiers who have become too powerful. Rather than Wall Street serving the real economy, Wall Street has enslaved it. Financialization has put the cart before the horse.

The evidence for financialization is everywhere. In 1987, financial services accounted for 5 percent of the S&P 500 total market capitalization. Twenty years later, the financial services market makes up more than 20 percent of that index. At the same time, trade-sensitive industries, such as manufacturing, have declined in economic importance. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, manufacturing was 21 percent of GDP in 1980 but has fallen to 12 percent in 2008. Finally the U.S. Department of Commerce reported that financial services, at $241 billion, were among America’s highest export categories in 2009.

Even more disturbing is the prospect that there may be nowhere in the world to escape its pernicious effects. According to McKinsey Global Institute’s annual global mapping report, the interconnectedness of world financial markets has been growing exponentially. Just prior to the credit crisis, cross-border capital flows exceeded $6 trillion, almost quadrupling since 1995. Moreover, debt in the form of cross-border lending between banks and non-financial institutions was the largest component, accounting for a whopping 42 percent of total capital flows. In contrast, cross-border mergers and foreign direct investment together only accounted for 15 percent of total cross-border capital flows. Rather than greasing the wheels of global commerce, financialization has already proven that it can induce the entire world economy to fall off a cliff as we have witnessed in the aftermath of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

Crisis is a natural state of affairs for financialization since the problem is never solved—it merely moves around geographically. Starting in the 1980s we had the Latin American crisis, followed by the Mexican crisis, the Long-Term Capital Management scandal, the Asian crisis, the Russian crisis, and the dot-com bubble before we finally had the subprime crisis, which hit the whole world. Although the central banks of the world came together to avoid a liquidity crunch to keep the world from falling into another depression, none of the underlying problems were fixed, the most egregious one being too much capital from too much leverage. That leaves the granddaddy of all crises—a reserve currency crisis—looming before us.

The root cause is deregulation of the financial system that empowered financiers to overstep prudential rules that originally ring-fenced them. Deregulation enabled financiers to control the means of production and the economy rather than merely assist in the process. Interestingly in the United States, both political parties supported financial deregulation. Under the Clinton administration, Glass-Steagall was revoked and over-the-counter derivatives were allowed to multiply freely without being subject to the same scrutiny as stocks. Under the Bush administration, the SEC raised the permissible leverage ratios for banks. The cumulative effect of restrictions that were dismantled heightened financiers’ abilities to grow exponentially wealthier with far greater ease than the rest of the economy. This became possible because financiers had access to vast amounts of leverage without having to pay the consequences. To build a factory and turn a profit selling tangible products could take years, while amassing a fortune through a single financial transaction took only seconds to complete.

Great wealth begets great power. By 2008 when the financial crisis hit, the financiers at the largest firms had become so powerful that all the rules were changed on the fly.2 Like sovereign nations, they can’t go bankrupt.3

When assets and the means of production can be easily separated from the original owners who have invested hard-earned savings and sweat equity into their assets, it creates a situation in which the new owners, the financiers, do not have the same interest in the success of these assets. Without an emotional stake, they are likely not to give the assets the same level of care as the original owners. For the person who uses his or her own capital, sweat equity, and valuable time to build an asset, there is nothing more demoralizing than to see a financier use the power of leverage to seize control of the same asset through financial means. Whether such financial means are called leverage buyouts, private equity, distressed investing, or hostile takeovers, such financing behavior can sometimes border on legal theft. Though legal, these methods allow a person or group of persons to take possession or control of someone else’s property via financial sleights of hand based on terms that the original property owner would not have agreed to had the negotiating power been more equal.

Private Equity Pirates

Private equity firms like Kohlberg Kravitz Roberts & Co. (KKR), Carlyle Group, and the Blackstone Group, as well as all the large multinational banks like JPMorgan and Citigroup, have taken over both public and private companies by borrowing large amounts of money from the bond markets to fund their purchases. According to Thomson Reuters, there were 1,382 transactions in 2007, representing a 30-fold jump in private equity deal volume between 1995 and 2007. The amount of money followed a similar trajectory. In 1995, only $28 billion was engaged in this kind of financial activity. By 2007, it had reached $797 billion.

A vast majority of these transactions are done for purely financial reasons, which are often at odds with the national goal of creating jobs or driving innovation. The financiers typically target cash-rich companies in order to extract the cash from the company’s balance sheet. They do this by paying themselves large dividends once they control the companies. As soon as these financial players take control of a company, they temporarily hire turnaround artists from restructuring firms like Alvarez and Marsal to fire employees at the newly acquired company. Firing people is the preferred method of how these financiers “add value” and “increase profitability and efficiency” because cost cutting is the easiest way to increase profits of a company in the shortest amount of time.4 Increasing sales, on the other hand, is usually a much more difficult task and requires much more specialized knowledge. But since these financial players are primarily interested in quick profits through financial engineering, they customarily sell the same acquired company back into the public markets or sell it to another company for a profit once the costs have been cut to the barest minimum. Avis is an example of a company that was bought and sold over a dozen times between various financial players. Every time the company was bought and sold, the company experienced employee turnover. The company is arguably no better off than when it started.

Since the 1980s, these financiers have popularized and replayed this same cookie-cutter transaction thousands of times over with companies they claim they have “improved operationally.” The reality is that what the vast majority of these financiers have accomplished is the equivalent of furniture rearranging. While they reaped larger and larger profits for themselves, millions of American employees were fired, and future investments in research were sacrificed. Furthermore, the investment portfolios of these financial elites not only include ownership of entire companies all over the world but increasingly include public assets like stadiums, bridges, and ports. Taken to its logical end, it is possible that they could eventually own entire states, as desperate governments around the world have no choice but to privatize public assets in order to raise cash for the their now-empty public coffers. After all, Citibank alone, whose offices span 140 countries, made more money in 2010 than the poorest 10 countries combined.

Traitorous Traders

Another highly disruptive financial activity involves carry trades, in which a trader from the developed world—namely the United States and London—borrows money in the cheapest currency and reinvests it in higher-yielding or higher-return investments for a quick profit, usually through hedge funds and large multinational financial institutions. An example of a carry trade is the money U.S. banks have been borrowing from the U.S. Federal Reserve at essentially zero interest rates. These financial institutions take the interest-free money and reinvest it in Treasury bonds, stock markets, corporate bonds, derivatives, other currencies, or commodities. The large amount of borrowed money that goes into these other financial markets artificially drives up prices for every financial instrument and commodity around the world. The money used for such purposes has reached hundreds of trillions of dollars—many times the entire world’s GDP—because printing money via leverage requires nothing more than a simple computer keystroke. The only limit to such activity would be through financial regulation. But since regulators in developed nations, particularly in the United States, have been fairly liberal and permissive to the entities they regulate, the capital at the disposal of these financial institutions has become virtually limitless.

Inevitably, when the rich nations provide their financial institutions loans—that are tantamount to free money when interest rates are held near zero—to invest in however they please around the world, this hot money as it is known, can cause serious economic harm. In the United States, financial institutions were loaned over $2.5 trillion by the Federal Reserve to rebuild their balance sheets.5 But instead of using these funds to provide loans to real economy businesses in the United States, these financial institutions lent the money to hedge funds or used the free money to speculate in various financial markets for easy profits.

Some of this hot money has been used to purchase long-dated U.S. Treasuries (Treasuries with long maturities) and riskier corporate bonds. These large bond purchases have driven bond yields so low that borrowing costs for corporations returned to the same rates as it was just before the 2008 financial crisis.6 Many expert observers believed that credit risk was being systematically mispriced once again. Even more have become skeptical of the Federal Reserve’s credibility as a guardian of stable monetary conditions. Announcements of quantitative easing by the Fed were viewed as mere money-printing exercises fueling more dangerous economic bubbles.7 Rather than help solve the problem of America’s overreliance on debt in our financial system, the Federal Reserve has been increasingly seen as the source of the problem.8

Other hot money has gone into stock markets, artificially driving up stock prices so that the wealthy who own the majority of these assets will accrue the majority of the benefits. The artificially rising stock market also encourages more speculation from people who would otherwise find work with regular pay. When average citizens feel that they can make more money gambling in the stock market than in working at a real job, they are more likely to withdraw from being productive citizens in the real economy. A look at online brokerage data supports this trend. Prior to the 1970s, day-trading was practically nonexistent among small investors because of long settlement dates and higher commissions. But according to quarterly reports several decades later, TD Ameritrade, Schwab, and Etrade together account for about 16 million customer accounts and 540,000 trades a day. The total number of online accounts and daily trades may be multiples higher since many retail brokerage firms such as Fidelity and Scottrade also offer day-trading platforms. The total U.S. labor force is only about 150 million, according to the June 2011 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. If this trend persists and day-trading becomes more popular, America could become a nation of gamblers with no one left willing to work.

Hot money has also flowed into global commodity markets causing harmful inflation everywhere on the globe.9 Skyrocketing prices for precious and base metals can hurt manufacturing profits and drive companies out of business for everything ranging from autos to medical devices. Rapidly rising food inflation is causing starvation among the poorest populations in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, prompting widespread riots and protests.10 While the Federal Reserve may deny responsibility for creating these speculative hot money flows, the trouble is that nothing, not even weather disruptions, can explain the coincidentally sharp rise in everything around the world since the Federal Reserve began its unprecedented money printing of trillions of dollars.

Finally, hot money has flowed across nations’ borders swiftly, causing much economic instability to developing nations offering higher interest rates. While some U.S. regulators, like the Federal Reserve, have argued that it is good for developing nations to receive capital, they fail to distinguish between the type of capital that is harmful and that which is beneficial to economic development. Harmful capital is the hot money that is extremely short-term in nature. The money comes in to buy foreign currencies and sovereign debt, causing import and export prices to change so dramatically that businesses are unable to establish terms of trade for any length of time. Such currency volatility hurts cross-border trades of real goods and services. International trade can again grind to a halt as it did in the years leading up to World War II when businesses had difficulty pricing items due to rapid currency debasement from Western countries seeking to make their exports more competitive. Instability in these markets can also lead to widespread bankruptcies that leave millions unemployed. The local businesses in these developing nations have no effective way to protect themselves from persistent volatility other than to buy foreign exchange contracts that guarantee specific prices. But the financial contracts themselves can be priced expensively so that buying them essentially would have the same effect as passing all the hard-earned money in the real economy back to the financiers. In any case, the economic situation for these developing countries has been rigged to favor the financiers under the mantra of “free market capitalism.”

The Secondary Effects

Having too many financial professionals has led to shortages of other professionals. The Yale Daily News reported as early as 2005 that many of its science majors were “selling out” for higher-paying business jobs such as those in finance. A whopping 58 percent of Harvard’s 2009 graduating students went into banking, a career choice that could certainly help pay off their large student loans. According to Reuters, Wall Street paid cash bonuses of $20.8 billion, the fifth-highest on record in 2010.11 That number translates to an average cash bonus of $128,530 per person, which is in addition to the base salary. The compensation at some financial firms was even more extreme. The average worker at Goldman Sachs, which includes secretaries and recent graduates, earned $498,000 in 2009 and $430,000 in 2010.12 Fred Merkel, a high-frequency trader for Bank of Montreal, surmised that even in 2011, large multinational banks were still handing out employment contracts to individuals with upfront guarantees of millions of dollars in compensation. In contrast, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the average salary for engineering managers of all types was only $125,000 in 2010.

Such a brain drain out of the sciences comes at a cost to technological and scientific endeavors that produce real goods and services. The creation of things such as preventative drugs and clean energy can improve the standard of living for more people than would the creation of more financial contracts. For example, according to National Review columnist Jerry Bowyer, the United States cannot afford to implement a universal health care program because there are not enough medical professionals in the country to service the additional 80 million uninsured patients. Similarly, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal also reported that the shortage of doctors has fallen below the safe ratio of 2000 patients per doctor. Fewer people are choosing to practice medicine largely because they do not feel adequately compensated for their time and risk when compared to Wall Street professions. The insurance industry, for instance, has largely usurped the profits that would otherwise be used to pay healthcare professionals. Dr. Klaus Lessnau who oversees pulmonary research at Lenox Hill Hospital and New York University resents that hospital management makes more money than the most senior surgeons. As a result, the supply of workers in areas such as the medical profession that deliver goods and services of real value to the economy have been curtailed by the financial industry.

If financialization is left unchecked, America will lose its competitiveness, its innovative dynamism, its way of life, and will slowly transform into a society that may more resemble a caste because social mobility will become increasingly difficult. According to Stephen Kaplan, professor at the University of Chicago, there are “more than twice as many Wall Street individuals as Main Street individuals (non-financial top executives) in the top 0.5 percent and the top 0.1 percent of the adjusted gross income (AGI) distribution.” It is no surprise then that the city with the most billionaires in the world, with a total of 45 according to Forbes, is New York City, dubbed by CNBC as the finance capital of the world. Once upon a time, the robber barons dominated their respective industries and amassed enormous personal fortunes. Today, the financial elite have become their equivalents in modern society. The difference is that the robber barons at least built great infrastructure for America, such as railroads, while Wall Street titans have left nothing of lasting value for society.

Furthermore, wealth is highly correlated to power. According to G. William Domoff, professor of sociology at the University of Santa Cruz:

Power is defined as the ability or capacity to realize wishes and reach goals even in the face of opposition.… Wealth can be seen as a “resource” that is very useful in exercising power. That’s obvious when we think of donations to political parties, payments to lobbyists, and grants to experts who are employed to think up new policies beneficial to the wealthy. Wealth also can be useful in shaping the general social environment to the benefit of the wealthy, whether through hiring public relations firms or donating money for universities, museums, music halls, and art galleries.… Certain kinds of wealth, such as stock ownership, can be used to control corporations, which of course have a major impact on how the society functions.… The United States is a power pyramid. It’s tough for the bottom 80 percent—maybe even the bottom 90 percent—to get organized and exercise much power.13

Say No to Finance

All of this capital havoc had been wreaked on nations, especially poor ones, for decades until China came onto the scene. During the Asian crisis of 1997, China watched closely how financial capital affected the real economy of all their neighbors from Malaysia to South Korea. With the wisdom of that experience at hand, the CCP was determined to ensure that such instability would not be allowed to dismantle the hard work and fortunes of its own people. Rather than listen to the Washington consensus, they decided to delay the development of their financial system and focus instead on developing their real economy first. As a result, their industrial sector grew rapidly, protected by an environment of stable prices due to a tight rein on the financial sector and a pegged exchange rate.

China’s solution to financialization is to turn hot money into patient capital. Patient capital is direct investment in the real economy, such as building infrastructure and creating businesses that offer products and services people need for survival. For example, foreign direct investments by American companies in China to build research and development laboratories, manufacturing plants, and retail outlets have been granted the right to enter and exit the country unhindered. Unlike financial capital or hot money, patient capital doesn’t slosh around the economy looking for the next big payoff. Patient capital can enter and exit across borders without causing economic harm because it assists the growth of the real economy rather than undermining it.

Another reason that China has flourished so remarkably is that its citizens had limited opportunities to speculate and squander their savings. The only way out of poverty for most was through old-fashioned ingenuity, hard work, and long-term planning. As an example, hedge funds were illegal in China before 2010.14 As a result, millions of real economy companies and trillions of dollars worth of goods and services were created. According to China’s official statistics, China’s GDP was only $306 million in 1980. By 2009, China reached a GDP of $4.9 trillion, surpassing Germany as the world’s largest exporter and third largest economy in the world

China does have rapidly growing stock markets and a burgeoning bond market where unsophisticated citizens can speculate. There are even brokerage firms that host individuals who just want to day-trade their savings all day. But compared to the United States, the trading in financial markets in China is miniscule, accounting for less than a quarter of its GDP. In contrast, U.S. trading of its stock markets in 2000 was 145 percent of its GDP. By end of June 2010, U.S. trading in financial derivatives was $583 trillion, while its GDP was only $14.8 trillion.15 In other words, trading in the over-the-counter derivatives market alone was 40 times larger than the nation’s entire GDP for a year.16 This trading doesn’t even include the trillions that are traded in the equities, bonds, and foreign exchange markets. With so much money that can easily be made trading other people’s money, what economic incentive is there to build anything of value? Why become an entrepreneur in America, which would require years of labor that could still yield no material success, when it is so easy to become a trader or an investment banker and earn millions, or even billions, a year with relatively little effort? The choice is clear, and the U.S. government and Federal Reserve have been tacitly supporting this choice to the detriment of working people.

To put it in stark terms, there would be no China miracle if China followed the same monetary and fiscal policies as the United States. Unquestioningly, its economy would be ruined like the economies of so many other nations that have let Wall Street get ahead of the real economy. While China’s pegged exchange rate has been accused of being manipulative, China certainly was not the first nation to follow such policies. During the era of Bretton Woods, shortly after the end of World War II, Singapore, as well as Japan and Germany, experienced rapid economic development due to pegged exchange rates. Bretton Woods was a system of fixed exchange rates that 44 Allied nations adopted in an attempt to avoid the currency manipulation that preceded World War II. This idea has been resurrected as a topic of conversation among those in financial circles who do not see monetary policy by the Federal Reserve as legitimate. With a fixed exchange rate, financial institutions cannot interfere with the development of the real economy through foreign exchange markets and their derivative products. Arguably, the Industrial Revolution would not have been possible in the United States and Europe had it not been for the stabilizing effect of the gold standard during the period before World War I. With major currencies pegged to gold, central banks and financiers didn’t have the power to manipulate currencies to their own advantage. The real economy flourished with innovation and prosperity for the benefit of the larger population during that time. So from a historical perspective, keeping finance in check and developing the real economy makes great empirical sense.

China’s foresight became obvious to me when I went back to Shanghai in 2006 to do some research on China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). While meeting with representatives from Credit Suisse, Deutche Bank, and other firms, I had discovered that the Chinese officials were deliberately moving slowly on initiatives to develop the financial sector. Aside from the fancy stock exchange that was built, the Chinese dragged their feet on other financial proposals for futures trading and the liberalizing of other derivative markets. Submissions to government authorities would seemingly land in the wastebasket as getting government responses to these banks frequently lasted two years or more while responses to other industries were markedly more prompt.

I later learned that China had set up specific research arms that were independent of banks and brokerage units to investigate the likely effects and possible unintended consequences of permitting such financial products into the financial marketplace. In many ways, the Chinese method of financial regulation is similar to the process used by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve new drugs. Before a drug can be commercialized in America, the drug must undergo rigorous testing from clinical trials and be evaluated against a long list of safety measures. Likewise, the Chinese financial regulatory authorities independently conduct investigations on financial products and policies. Once researched, they review the results before giving approvals. But in the United States, new financial products are invented daily and sold to investors who are willing to purchase them. Financial innovations are not subject to reviews or approvals by United States financial regulators so long as the financial products do not violate existing laws. As a result, the alphabet soup of credit derivatives worth trillions of dollars escaped regulatory scrutiny from all the U.S. financial regulatory authorities. These were the same financial products that almost caused the collapse of the global financial system in 2008.

In addition to precautionary testing of financial products, the Chinese also require that loans reach maturity before their bankers are paid for the transactions. This policy ensures that bankers are not disaggregated from the borrower and will retain responsibility for the loan quality of the loans underwritten. A major problem with the securitized products leading up to the financial crisis of 2008 was that bankers were paid a commission for simply processing a loan application. If the loans went south, the bankers did not have to assume any responsibility for the losses. Making sure that financiers have skin in the game would help rein in irresponsible risk-taking behavior.

The Chinese government also announced in 2010 that it plans to open up other industries that were formerly closed to private investment, such as infrastructure, health care providers, and even certain types of banking. The number of people who will participate in these opportunities for wealth creation will multiply. By ensuring that other non-financial industries have a chance to flourish without out-sized influence from financiers, the Chinese government will help create an economy that is entrepreneurial, diverse, and robust.

Currency Manipulators

China’s strong economic engine as a result of its peg to the U.S. dollar has been a blessing for the entire world except to the financiers. After the 2008 financial crisis, China single-handedly brought the world out of recession, assisting countries from Brazil to South Africa to resume strong economic growth comparable to pre-Lehman levels.17 Had China not been in the picture, the world would have most definitively hit depression levels because no other country was strong and large enough to drive demand when demand vanished from American and European consumers mired in crippling debt. China was able to engineer this feat because the financial institutions in China were heavily controlled and regulated by the Chinese government. Financial institutions like hedge funds were outlawed, and banks were prohibited from gambling with depositors’ money. Instead, the financial institutions were directed by the central government to lend to real economy projects that would generate millions of jobs for the Chinese people immediately as well as far into the future. This included many plans for infrastructure, such as additional passenger terminals at airports that put people to work in the short term while laying the groundwork for future economic activity.18 These projects in turn required importing many resources from countries around the world which kick-started those foreign economies as well. Two years after the crisis, thanks to China, the economies of most developing countries had returned to growth levels comparable to pre-crisis levels. As the IMF reported, emerging market economies rebounded into positive territory in 2009 while developed countries experienced negative growth, and by 2010, emerging market economies exceeded their 2008 growth rates, growing on average 7 percent per annum.

But despite the enormous role China played in saving the economic fortunes of the world, including those of many U.S. businesses that were able to return to profitability by selling to the growing Chinese consumer class instead of indebted Americans, Washington and Western media have been relentless in filling the airwaves with vituperative accusations of China being a currency manipulator. Washington needed a scapegoat to blame for the enormous economic woes the nation suffered from the hands of its own Wall Street cronies and decided to use China as the convenient whipping boy. Even more sinister and outrageous, on March 2, 2011, the Pentagon went so far as to suggest that foreign countries such as China could have damaged the Western financial system.

Anyone who has worked in China knows this is impossible due to China’s complete lack of financial sophistication as well as its extremely conservative stance toward its financial reserves. The author of the report making such claims is Kevin Freeman, who said on the record that “the two major strategic threats, radical jihadists and the Chinese, are among the best positioned in the economic battle space.”19 He jumped to these conclusions when he admittedly had no evidence about the two unidentified traders he claimed caused the stock markets to go down and no evidence that they even happened outside U.S. borders.

Given the number of hedge fund managers, such as David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital, who were calling for Lehman’s demise publicly, it is certainly possible that the traders were in fact U.S. institutional money managers with trillions under management. These money managers could have borrowed amounts that were several times the worth of their net assets under management from the large multinational banks who offered prime brokerage services. Then they could have used this borrowed money to make risky bets that included shorting financial stocks.20 (Shorting a stock is a trading strategy that enables one to profit if a stock falls in price.) By using both their own assets and the borrowed capital, these money managers could have placed bets and increased their profits exponentially if trades moved in their favor. Hedge funds alone had around $2.2 trillion under management in 2007 right before the credit crisis, according to International Financial Services London, a UK lobby group. Naked short selling, an easy strategy by stock traders to drive down share prices of stocks, was widespread in the United States, especially among hedge fund managers, up until September 2008 when the SEC restricted the practice in response to the financial crisis.21 Short selling was illegal in China.22

Financial Warfare

The inverse situation, however, is far more likely. According to Marc Chandler, head of currency research at Brown Brothers Harriman, the financial research arm of the CIA is producing simulation games of financial warfare, hiring currency specialists who work in private investment banks to provide expertise. Furthermore, Wall Street has had decades of practice outsmarting and neutralizing developing countries with financial warfare through financialization and is ready to make China its next victim. China represents the last and final frontier for the financiers to prey with abandon, and Wall Street can’t wait. Sophisticated Western hedge funds and investment banking proprietary traders dream of the day they can initiate a financial attack on China’s currency the same way George Soros famously broke the Bank of England in September of 1992. On the day now known as Black Wednesday, Soros walked away with billions. Financiers have more recently tried to break up the euro, but their efforts have been continually thwarted by China’s opposite move to save it by its large purchases of Spanish and Greek bonds.23

One hypothetical scenario is that the U.S. government will continue to pressure China to make its currency float freely on the foreign exchange markets while at the same time run up its fiscal deficit unsustainably in tandem with the Federal Reserve’s inflationary money-printing activities. By monetizing Treasury debt and holding short-term interest rates below global inflation rates, the Federal Reserve encourages speculators to drive up the prices of most everything in the world. If China is forced to decouple its yuan peg to the U.S. dollar due to painfully high inflation that it is importing as a result of loose U.S. monetary policies, sophisticated hedge fund managers and other currency speculators will pounce on the opportunity to attack China’s currency.24 Speculators can easily drive the value of the yuan to extreme highs or lows since they can all make the same one-way bets. In 2010, currency traders drove the euro down from $1.50 until it was almost on par with the U.S. dollar by responding to speculation that the euro would break up.25 These speculators also are permitted much higher leverage in their currency trades (400 to 1)26 by brokerage firms than most retail stock traders get (2 to 1). This arbitrary rule gives traders more firepower to force a currency to move according to their whims. Such a political move against the wishes of the Chinese government by the U.S. government would be quite effective in taking down China’s economy without necessarily hurting large U.S. multinationals. The reason is that large U.S. companies could simply buy reasonably priced financial instruments from the American financial firms to protect themselves from a wildly fluctuating exchange rate while Chinese companies would be at the mercy of American financial firms who could discriminatorily charge outrageously higher prices for the same financial protection. Chinese financial firms have yet to gain permission from Chinese regulatory authorities to offer a variety of sophisticated financial hedging products to their customers. Although slowly catching up, they also do not have a deep bench of financial experts to compete with the likes of Goldman Sachs. If Chinese companies cannot protect themselves from wildly fluctuating prices from foreign exchange volatility on everything from imported commodities to exports, they would all be unable to conduct international business and thus go bankrupt.

The current foreign exchange market structure still makes it impossible to prevent speculative attacks. Unlike a stock exchange, foreign exchange is unregulated and conducted in over-the-counter (OTC) markets all over the world, which means that the trading happens over the phone, fax, or electronic network in a decentralized manner because there is no exchange or meeting place for this market. The lack of a centralized market place, the lack of transparency, and the lack of technology to enable central banks to deter currency attacks make foreign exchange markets a particularly vexing problem for governments everywhere, except the United States because of its reserve currency status. Speculators can attack a currency by launching trades in various geographic locations hiding behind and acting through multiple banks. For instance, Soros’s fund could launch a currency attack on a country by placing separate trades with Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, and others to sell a currency at any price. As a client of these financial firms, Soros’s firm’s identity is protected and unknown in the vast currency marketplace. The currency in question could start falling in value, and no one would be able to trace the trades back to Soros. So without a sophisticated system in place, central banks have no way of monitoring in real time what is happening. By the time an attack is detected, it is too late to do much of anything, while the attacker could walk away with billions of dollars in one day and be ready to come back for more the next day. Since some large speculators, such as Duquesne Capital Management or Quantum Fund, remain unregulated, their speculation can increase volatility in prices and cause the value of a currency to deviate far from its fundamental value while escaping any regulatory demands to stop such harmful behavior. This manipulation of currency value could disrupt trade, distress many domestic Chinese companies, cause economic recession, and even induce a civil crisis or depression in extreme cases.

Soon after the 2011 earthquake in Japan, deputy finance minister Fumihiko Igarashi said, “The yen’s rise was driven by speculators. If we caved into such speculators that took advantage of people’s misfortunes, the Japanese economy would be ruined, and the whole world economy would be harmed.”27 In response, the G-7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors admitted that government intervention in exchange markets is justified when “excess volatility and disorderly movements in exchange rates have adverse implications for economic and financial stability.”28 The effect of a rapidly rising yuan would be no different. In simple terms, without a sophisticated system in place, foreign hedge fund managers could walk away with billions of dollars of reserves that were earned by real economy businesses operating in China.

Why would the United States potentially favor such a scenario? Historically speaking, the rise of a nation that challenges the power of another has often provoked great insecurity that leads to instability and wars. Today, with unemployment stubbornly high and the U.S. Army still guarding the same Korean border that saw vicious fighting with Chinese forces in the 1950s, the danger of kicking off World War III is remote but not impossible. One could argue that one way to diffuse the economic tensions that can lead to war would be to destabilize China’s economic situation so that it will never have the economic means to catch up militarily to confront the United States. Compare this to how Israel is suspected to have used a cyber-attack through computer viruses to neutralize Iran’s nuclear program without launching a full-scale war.29 In a scenario using financial speculation to attack China, it would be more difficult to pin blame on the United States for victimizing China in this way since the terrorist speculators would be almost impossible to trace. Repeated speculative attacks could slow China’s economic advance dramatically as top government officials are forced to divert attention away from other issues in order to deal with the currency problem and the resulting economic upheaval that could arise from such destabilizing economic forces. While currency attacks could be as destabilizing as a permanent revaluation, the difference is that large foreign multinationals could shield themselves by purchasing foreign exchange derivatives from large Western multinational banks that are all too happy to win additional foreign exchange business. Nonetheless, if this scenario were to unfold, it could severely damage China’s economic efficiency and force the Chinese citizens to suffer a worse fate than the Japanese, who already enjoyed a much higher standard of living comparatively speaking when their economy crashed in the 1990s.

Such may be the sad reality in the end if the United States pursues this foreign policy strategy, causing the whole world to lose a productive force. If China had never opened its doors to the world, hundreds of millions of people probably would not have escaped poverty. Indeed it was only about a dozen years ago that the Economist had a picture of Africa on its cover with the title “Hopeless Continent.” Chinese foreign direct investment in this continent turned things around. After the financial crisis, China had an integral role in preventing a worse catastrophe, which was a great blessing for every nation, including the United States, whose companies hit record profits selling to China in 2010.30

Dark Ages—Again?

Against the backdrop of the growing wealth inequality and economic stagnation in the United States, innovation—widely accepted as a necessary ingredient for sustainable economic growth and wealth creation—also shows signs of heading in the wrong direction. Jonathan Huebner, a physicist who works at the Pentagon’s Naval Air Warfare Center, studied the rate of significant innovations as catalogued in The History of Science and Technology. According to Mr. Huebner, the rate of innovation peaked in 1873 and has been declining ever since. He calculated that in terms of important technological developments, the world’s current innovation rate is roughly seven per billion people per year, comparable to the rates back in 1600. If extrapolated, by 2024, innovation rates will have stagnated to the same level as it was during the Dark Ages.31 Indeed, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, the world produced many inventors, including Thomas Edison and Alberto Santos-Dumont, as well as pioneering scientists, such as Marie Curie, who created life-changing inventions and made breakthrough discoveries that don’t have their equivalents today.

While authors such as Ray Kurzweil and Matt Ridley would argue that innovation is increasing exponentially based on past trends, anecdotal evidence in everyday life doesn’t appear to bear out their claims. After all, isn’t it odd that it’s always the same handful of companies—Apple, Google, Microsoft—that are most frequently cited as leaders in innovation when the United States can boast hundreds of large industrial companies? Are these other companies innovating at the same level? How come we haven’t had a medical breakthrough like a cure for cancer after decades of research and billions of dollars later? Why was it that during the Industrial Revolution inventions spawned giant companies across multiple industries, yet, since then, only the information technology industry has followed that pattern a century later? Aside from those in information technology, why haven’t there been more revolutionary inventions—revolutionary meaning that they fundamentally change the quality of life and serve as taproots for entrepreneurial offshoots? After all, more information, talent, and money exist now than ever before in history, yet we still haven’t journeyed to distant galaxies, traveled through time, discovered the secret of immortality, or enjoy the easy life that science fiction promised us.

Two theories have been advanced by Huebner for why innovation rates are slowing to a crawl. The first is the low-hanging fruit theory: early innovators plucked the easiest-to-reach ideas, so later ones have to struggle to crack the harder problems. Or it may be that the massive accumulation of knowledge means that innovators have to stay in education longer to learn enough to invent something new and, as a result, less of their active life is spent innovating.

Former neurobiologist Paul Roossin worked as a researcher in the Human Language Technologies Laboratory at IBM’s T.J. Watson Research Center. He doesn’t believe that massive knowledge accumulation is the limiting factor. He said that sciences are rather easy to understand, given that most of them follow a certain logic that is consistent across scientific disciplines. Just as the social sciences are interrelated, so are the hard sciences. He claims his knowledge of chemistry is just as relevant to understanding biology and physics as was learning the rules specific to those disciplines. His ability to consult across sciences in equal fashion is not unusual.

The student exhibits at the 2010 World Science Festival held in New York City seem to lend support to Paul Roossin’s claims. There, public high school students who had won a science contest displayed their own original scientific research that was on par with some of the best research labs in America. For instance, searching for the gene responsible for a certain type of cancer, one junior wrote a software program that simulated biological functions hundreds of times faster than if one were to record that behavior through empirical studies.

Today’s potential inventors do have many advantages and tools that past inventors did not have, such as computer-aided design software at their disposal, which can speed up innovation. The exponentially faster and higher computing power available in the modern era should more than offset the greater time required for one to accumulate more knowledge. After all, information can be accessed and analyzed so much more quickly than a hundred years ago. Moreover, according to Paul Hoffman, author of Wings of Madness, the morality of scientists a century earlier drove them to conduct experiments using themselves as subjects. This had the effect of shortening their own life spans when compared with scientific inventors today. This further renders Huebner’s explanations less plausible.

A theory Mr. Huebner did not consider is the systematic suppression of innovation in most industries. Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter popularized a theory about the destruction of established companies through disruptive innovation called creative destruction. Could this be what is happening in limited circumstances? Mr. Schumpeter posited that the entry of innovative entrepreneurs would succeed in gaining market share in a capitalist society and thus destroy the profits and position of established companies while powering the economy ahead.

But the obstacle to creative destruction is described in Mancur Olson’s book The Rise and Decline of Nations.32 A leading economist, Mancur Olson describes how lobby groups organize over time to alter polices in their favor. Coalitions form to prevent change that would hurt its members. Since the burden is shared by the entire population and therefore unlikely to meet public resistance, these benefits initially seem inconsequential; but over time, the growing number of lobby groups and the benefits accrued to them end up stifling the nation as a whole.

It is clear that large established companies would not have any interest in seeing their market share or profit disappear to upstart entrepreneurs such as those behind Elastol that may have superior, innovative solutions. They would fortify their positions as much as they could by insisting on laws and policies that would protect their turf. The large and growing number of lobby groups in the United States—more than 17,000 in 2007—supports this hypothesis.

The United States is certainly not alone in experiencing this phenomenon. In some places in Latin America, a single company may monopolize an entire industry. The sons and daughters who take over control of a company from their parents ordinarily are not particularly innovative but have the financial resources to create laws that block new entrants from challenging the monopoly. Inefficiencies begin developing because there are no competitors to force improvements. When the established monopoly player cannot keep up with international competition, production starts sliding and domestic workers get laid off. As a result, the entire economy of the community suffers.

If the United States doesn’t want to lose its competitive edge and experience this very predictable fate, it must give power to the entrepreneurs in the real economy. This, above all else, requires overcoming the inordinate amount of power that Wall Street has garnered over the years.

Back to Basics

The United States could take a page out of China’s playbook by restricting banks to traditional banking activities—making loans and taking deposits—as one possible solution. As Paul Volcker vigorously pointed out, the Glass-Steagall Act that separated investment banking from the more utilitarian, commercial banking kept the United States safe from a financial crisis reaching Depression-like levels up until the law was repealed. In some ways, China’s financial regulatory system resembles the United States before Glass-Steagall was dismantled. The Chinese separate the functions between commercial banks and investment banks and have distinct regulatory agencies to govern them.

Lawrence Summers and others have argued that such a separation is unnecessary because that would not have prevented the fall of Lehman Brothers. Lehman, when it collapsed, was not also acting as a commercial bank. This argument has serious problems, however. Although Lehman remained an investment bank, the financial innovations that developed after Glass-Steagall was repealed blurred the distinctions between investment banking and commercial banking. Furthermore, when Lehman Brothers went down, just about every other financial institution was in danger of collapsing as well. Had the Federal Reserve not intervened with historic emergency measures like guaranteeing money market funds, Lehman’s downfall could have potentially wiped out the entire financial system. Even if we assume that Lehman couldn’t destroy the financial system, the bankruptcies of Citibank, JP Morgan Chase, or any of the other multinational banks that conducted both commercial and investment banking activities because of the dismantling of Glass-Steagall would most certainly have done the job. Due to the elimination of Glass-Steagall, the existing multinational banks have all become TBTF, a problem that didn’t exist before.

Reinstating lower leverage limits would also help solve the problem of TBTF. Part of the reason Wall Street became too powerful was the access to large amounts of leverage that they didn’t used to have. The debt-to-net capital ratio—or leverage ratio—used to be 12 to 1 but was lifted to 40 to 1 for broker dealers when Christopher Cox headed the Securities and Exchange Commission. Less leverage would translate into smaller balance sheets. While this would certainly hurt the profitability of large banks, the net benefit is that financial capital would not overwhelm the real economy.

Financial institutions also used to be more conservatively managed when they were private partnerships. When partner capital was at risk, financial speculation did not run rampant because few would put their entire net worth on the line. But in more recent years, access to public markets and other innovative legal structures meant that financiers had free options. In other words, bankers and traders were rewarded for any profits they made from risk-taking behavior but did not have their wealth taken away if their actions resulted in losses. Like gamblers playing with other people’s money, financiers had payoff profiles that encouraged speculation as opposed to prudent investments. If we balance the risk/reward tradeoffs more evenly, financiers will likely exercise greater self-restraint.

Proposals to reduce executive compensation have been advocated by populist groups. However, legislating such changes could become too arbitrary and create new problems. Under such a scenario, bank executives could find loopholes for compensation while regulations fail to reform the problem of a flawed incentive structure. A more straightforward way to reverse the brain drain into financial services is to follow the above prescription: limit leverage, increase personal accountability, and separate financial activities to provide more transparency and easier regulatory scrutiny. The consolidated effect of these three rule changes will naturally reduce the outsized profitability of financial services. Less profitability eventually will lead to lower compensation.

Finally, advocates for free-market capitalism should distinguish between capitalism for the real economy from capitalism for the financial community. China practices the former, encouraging capitalism to flourish in the real economy, which creates hundreds of millions of jobs and real wealth. Capitalism in the real economy enables large segments of the population to lift itself out of poverty into the middle class through real wealth creation. However, too much freedom in the financial economy can have the opposite effect. The failure of lawmakers to recognize the difference has contributed to the ascendancy of the financial sector to the most dominant position in the nation’s economy at the expense of many other industries. Today, a significant percentage of the powerful and wealthy rely on financial markets to make a living, creating too much capital being sloshed around the global economy that can set off another financial crisis. They must be weaned from borrowing capital as their main line of business and source of income. It will be challenging, but the world can’t afford another crisis of global magnitude.

If Americans want a healthier, more diverse economy, we should follow China’s example of limiting the power of the financial sector while investing in other industries that have been neglected. Green technology has had vocal supporters. But the amount of money that has gone into green technology research from the federal government is negligible compared to the trillions that have been lent to the nation’s largest banks with essentially no strings attached. Likewise, science funding to programs like NASA should be increased. Europeans have invested in a long-range plan to achieve energy independence by installing solar panels in North Africa, whose energy will be transported back to the European continent.33 Americans have made no equivalent investments.

Many of us have been misled by government and industry spokespersons who claim innovation is alive and well by pointing to the successes of the information technology industry. A closer examination of the facts reveals that the high-tech industry gave birth to many successful start-ups only because it was an area that was largely unoccupied. Information technology was so different from traditional forms of media that the early entrants, such as Bill Gates of Microsoft, sneaked through under the radar before anyone could stop them. The challenge is to allow entrepreneurship to flourish in more established industries.

The nearly insurmountable obstacles that handicap disruptive entrepreneurial activity are bad enough, but the enduring effect of these practices is the continual brain drain out of industries that need innovation to sectors that arguably don’t. As I briefly mentioned earlier, when people realize that it’s too difficult to buck the system, they eventually abandon the good fight to follow the path of least resistance. Furthermore, the people who receive large compensation packages from big established firms inevitably drive up the cost of living. It becomes increasingly difficult for real economy entrepreneurs to start and sustain technologically innovative companies without regular incomes that keep up with inflation. Technological innovation often requires far more time and resources than would creating a service-oriented company like a hedge fund. The risk/reward ratio is so unfavorable that fewer entrepreneurs will be willing to stick it out. Eventually, most won’t even consider a career in scientific fields and Mr. Huebner’s prediction that the world will enter a period that parallels the Dark Ages will surely become realized.

We may never know to the fullest extent what the collateral damage of this systematic stifling of innovation has done to America. However, it is highly likely that the dearth of new start-ups with disruptive technology has exacerbated the growing problem of unemployment. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are defined as under 500 employees, have been significant sources of employment in America, accounting for roughly half of the workers in the private sector.34 The taproot innovation called the Internet produced millions of small businesses that hired millions more. Where will the next taproot innovations come from if big industry conspires against the bright minds that dare to innovate and revive the economy?

The U.S. government can follow another of China’s practices by creating government-backed incubators of technology. Private venture capital firms in Silicon Valley and Silicon Alley in New York City have provided incubator space, business advice, and funding for social media start-ups, but U.S. venture firms do not typically extend the financial and social support to the families of entrepreneurs. Supplying living quarters and other amenities means that tech entrepreneurs can focus on developing new inventions and filing patents worldwide without the worry of eking out a comfortable living. China recognizes that such support is crucial to attracting entrepreneurs, especially older ones. As the Council of Competitiveness concedes, people in their fifties start twice as many technology firms than the stereotypical tech entrepreneurs in their twenties. Following China’s example would be a small investment relative to the potential payoff of starting the Third Industrial Revolution.

U.S. Government Hatchery

The United States currently has no such comprehensive innovation program in place. It has a Small Business Administration (SBA) that provides small business loans and has a program for creating Small Business Investment Companies (SBIC) that was supposed to provide government funds for venture capital. Unfortunately, the small business loans largely go to mom-and-pop shops, not to disruptive technological companies. The SBICs also have been known to funnel government funds to Certified Capital Companies (CAPCOs), which were originally conceived as an economic tool to create jobs by providing venture capital funds to small businesses unable to access traditional financing. However CAPCOs have largely proven to be scam vehicles for investors to arbitrage government funds for a profit without investing in a single company.35 Even if these government programs worked according to plan, they still do not offer the same comprehensive capital and security that the Chinese incubators offer.

U.S. private capital in the form of angel investors and venture capital have historically stepped in to fund promising entrepreneurs with great ideas. Thanks to a handful of visionary venture capitalists, a number of great American companies such as Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and Fairchild Semiconductors have created hundreds of thousands of jobs and substantial wealth to Americans and the world with their inventions.

But leaving it solely to private industry means that perhaps many more great ideas never get funded because the time and capital required to turn a great idea into a commercial product could be more than private investors are willing to give. Most of the major venture capital investments after the dot com bust have been in social media rather than in engineering, which characterized previous venture capital investments. These investments provide much quicker financial return to the private investors. However, save for the ability to connect and coordinate large numbers of people quickly—as in the multiple Middle East demonstrations in 2011—the real material benefit to society is much less consequential than a radically disruptive new invention that could revolutionize our lifestyles. Even the average investment to bring an incrementally improved medical product to market could require upward of a billion dollars and ten years, an investment horizon often too risky for most private investors and indeed most established companies.36 But investments in taproot technologies are the most important and most needed investments for our collective future. Acknowledging that private investment has its limitations and that we need radical new inventions to save civilization, we must have the government step in to bridge that gap.

The Long and Short of It

Modern commerce has no doubt been profoundly shaped by the theories of John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman on how to manage economies. The former emphasized both fiscal and monetary policy, while the latter gave money a starring role, by suggesting that monetary policy can affect economic growth through manipulating the money supply. We now know that these strategies have reached their limits since the boundless use of both has failed to resuscitate U.S. employment in any adequate way and may, in fact, derail any possible recoveries with the threat of unacceptable levels of inflation. Thanks to financialization, these theories no longer apply.

The lesson we need to relearn from China is that we must not let the financial services industry become too powerful. China does not have a better financial system than ours, but it does have one that is not all powerful. As Americans, we knew the wisdom of curbing financial power back in the 1930s. We need to reinstate those financial regulations in order to nurse the global economy back to health. Following China’s example, we also ought to provide incentives for pursuing productive real-economy activities because these activities are at an inherent disadvantage when compared to the relative ease and high compensation of financial services. Fostering true wealth creation will take more effort, ingenuity, and time to develop than financial activities. But relying on China alone for the next inventions will be too risky a proposition. China may be forging ahead, but to save the world, America must join in the race.