Chapter 6: How can creativity be saved?

Profile of a paramedic: the seven creative thinking strategies

We were with a group of ‘at risk’ school students, on a government-funded wilderness expedition that would, we hoped, help them get their lives back on track. The most troubled of them had run afoul of the law; for others their families had given up hope. This was a rescue mission for many of these boys — the last stop on a long road that had been leading to almost certain destruction. The expedition involved taking them into the wilds, far from all their regular negative influences, and allowing them to learn the consequences of their behaviours. It was a tough trip: the boys ended up having to camp on the side of a cliff when their navigation skills went awry, and they had to eat cold food scraped out of cans when they wasted rations in a food fight and got their matches damp in the process. They often had to set up camp in the dark, battle inhospitable terrain and deal with unfamiliar wildlife.

The biggest and final challenge of the trip was to be a long abseil, a 400-metre drop down a massive cliff. There was only one way to get out of the wilderness, and it involved scaling that cliff, but even the most intrepid of expeditioners would have been terrified by this precipice and the sheer drop to the distant valley floor below. The night before the students were to take the big plunge we took 10 of them across to the other side of the valley to view the challenge they would face the next day. As the sun set over the mountains, casting a rugged shadow across the valley, we looked over in awe to what was actually the biggest abseil in Australia, Mt Banks. Silence fell over the group of students as they contemplated dropping off the overhang. Although we had been preparing for and building up to this final challenge all year, all the students, even the toughest of them, went pale at the sight of the steep cliff face.

Fiery red-haired Jack was the first to ask what was on everyone’s mind: ‘*%#@! How do we get down this f---ing drop? We don’t even have a rope that’s 400 metres long, do we?’ ‘Yeah,’ agreed Robert. ‘We couldn’t carry a 400-metre rope — it’d be too heavy.’ ‘What other choice do we have?’ countered Dennis. ‘It’s the only way out.’

As evening descended on the valley, spirits sank and a deathly fear fell over the whole group, almost paralysing in its grip. Most students crouched on the edge of the cliff and grappled with the fear of the unknown, trying to imagine what they would be doing and how they would be feeling in 12 hours’ time.

The only way to get these kids down this mountain would be in small, achievable steps. Robert was right, we didn’t have a 400-metre rope, but what the students didn’t know at that time was that we wouldn’t actually need it. What we did have in our supplies were two 50-metre ropes that we could use to make the descent, one pitch at a time. What it was not possible to see from a distance was that the sheer cliff face actually had several levels of ledges that could be used as separate pitch points as we descended. These students had already successfully completed numerous 55-metre abseils, so it would be a matter of helping them understand that they need face the challenge only one step at a time, in manageable stages. Looking at the whole mountain, the students believed the task was impossible, but when the process was broken down they began to believe they could do it.

The next morning every student took the plunge. The first few were lucky as the fog had not cleared, so they dropped into cloud without being confronted by the scale of the drop, but when the cloud disappeared and the full pitch was revealed it took far more coaching from us to prepare the children psychologically. We finally got them all over the top, and eight hours (and seven pitches) later, all had reached the valley floor without incident.

Once they found they could break the problem down, we were able to help them to see how they could apply that principle to other parts of their life, including dealing with problems at school. Suddenly the paralysing fear of the apparently impossible had gone, and a whole new world of possibilities was opened up for them. Many of these students were dramatically changed by that moment, discovering a new confidence that they could face whatever challenges came their way. They saw the world from a new perspective.

No matter how creatively challenged people may feel, or how much damage the creativity killers have already wreaked, it is possible to achieve the apparently unachievable and to rescue creative thinking. Some individuals and organisations find the process hard to get started; others start off enthusiastically but then feel overwhelmed or get stuck somewhere along the way. The more this happens, the less optimistic and persistent they become. We have found it’s better to break the process down to make the jump easier, providing people with clear, incremental steps they can take. Even then some become impatient and try to skip crucial steps, and as a result fail to reach the solution they’d hoped for.

When you go ‘off-piste’ — or take a leap off a mountain! — there may not be a clear path for you to take. But no matter how challenging the terrain, with the right skills, equipment and planning, you can be ready to face anything, one step at a time. The process we will share in these next sections should help you to explore pathways to creative development in a way that provides specific practical and useful outcomes. We have broken the process down into seven strategies so you can confidently take one pitch at a time.

Creativity starts with the individual, but individuals often don’t allow their creativity to develop. Time pressures, deadlines, an unsupportive environment, fear of failure and bureaucracy can all paralyse creativity. What threatens it most, however, is lack of exercise. Because you are in control of your life, you can actively develop your creativity. When was the last time you actually set aside some time to try something creative?

Once there is individual buy-in and commitment to creative development, there can then be organisational change. People who don’t think they need to be creative will stifle creativity in a team, allowing the organisation to chug along inefficiently. A lack of individual creative competence will also inhibit customers’ requests, which will prompt them to go elsewhere. Customers and clients (internal and external) will innovate with or without your organisation, so you will need to proactively pursue creative development opportunities to stay ahead.

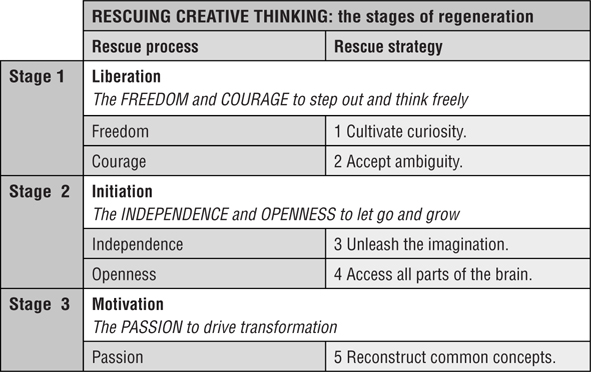

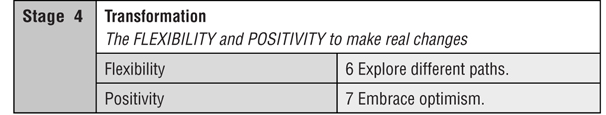

Developing creativity involves taking on a new thinking style. There are many different ways you can practise this style and release your creative potential. Just as there are four stages of degeneration in the death of creative thinking, there are four corresponding stages of regeneration we have identified as necessary in the rescue process:

• Stage 1: liberation

• Stage 2: initiation

• Stage 3: motivation

• Stage 4: transformation.

There are then seven strategies we recommend to assist with the rescue process (as illustrated in table 6.1):

Table 6.1: the Creative Thinking Life Cycle Model™ — the regeneration of creativity

Stage 1: liberation — the freedom and courage to step out and think freely

The first stage of the rescue process provides the platform for potential creative growth. It recognises the need for freedom, which opens up thinking in readiness for accepting new possibilities, and courage, which is the launch pad for stepping out on the intrepid journey.

Rescuer profile 1: freedom

This probing pioneer creates a mental state in which it is possible to feel safe and secure and to explore ideas without restrictions. Freedom encourages humble leadership and accessible work environments. It is a profile that is not restricted by preconceived ideas or concepts and is able to unlock challenges and open up possibilities. As a rescuer, freedom is ready to face any challenge at any time. Constantly finding new paths, and travelling cross country rather than on the beaten track, freedom is extremely resourceful and self-sufficient. It always wants to see what’s around the next bend, over the next mountain, beyond the next deadline, over the new horizon. The preferred rescue strategy of the pioneer is to cultivate curiosity. Freedom helps rescue you from control murder suspects whose main weapon is crushing coercion.

Consider Jason Kilar, who is not your typical CEO. Rather than enjoying the benefits that his status could provide or flaunting his power, he goes to considerable lengths to communicate modesty and humility. Instead of taking the grand corner office with the best view, Kilar is out with everyone else, sitting at a desk made partly from empty boxes. He takes a personal interest in all his new employees, taking them out to lunch to get to know them better and to find out from them what they would like to see happening in the organisation.

Writer and educator Gregory Ferenstein describes this revolutionary new approach to organisational structure that supports innovation, and explains the ideas this company and others like it have introduced. He explains how, as CEO of the multimillion-dollar video streaming giant Hulu,1 Kilar is taking some unorthodox steps. In his position he would have the right to enjoy the benefits of success, yet he sees a very important principle at stake here. He believes, ‘You will not attract and retain the world’s best builders in a command-and-control environment’. Andrew Mason, CEO of the similarly successful internet phenomenon Groupon, explains this concept further: ‘We assume that people are fundamentally good and people are responsible adults. The policies we have reflect those beliefs.’ Most organisations focus on setting up rules and regulations to deal with difficult employees, but Mason says, ‘The cost of creating bureaucracy and red tape that assumes the other 90 per cent of people are also bad is creating rules that encourage people to live up to the edge of those rules … Because the company is not showing them the respect and autonomy to get the work done in the way that they know it will actually get done, they’re treating the company with the same lack of respect’. Ferenstein explains that in these companies:

• Sales agents have access to real financial progress data so they can craft their own sales strategies rather than being set external targets.

• Employees work and sit together at interconnected desks of threes and fours, which removes the need for close managerial supervision and encourages ongoing discussion and open sharing of information.

It’s not surprising that Hulu and Groupon have both recently received awards for their exceptional commitment to workplace empowerment. (Pioneers of this empowering leadership style, which ensures freedom in the organisation, are the twentieth-century union movement and the Kibbutzim in Israel. Ricardo Semler introduced the concept of self-set salaries and employees voting for new managers nearly 30 years ago.)

Creating freedom in the organisation should not involve simply a superficial makeover; it needs to be built up from the foundations. Through establishing flatter management structures that help everyone to feel they have the potential to create, through establishing models of modest leadership, and through designing more accessible work environments that give the opportunity for employees to connect and collaborate, the kind of freedom that supports collaboration can be established. When it is, we’ll see more CEOs mixing with those who will ultimately make the difference in the organisation.

As we’ve discussed, children (and animals) who do not ‘free play’ when they are young can grow into anxious, socially maladjusted adults.2 Free play is an essential conduit to divert brain resources from dealing with the primitive survival functions so they can access creative thinking. If creative thinking is not exercised regularly, strong pathways in the brain cannot be established, and the ability to think creatively can actually wither. People who have enjoyed free play from an early age are better prepared to develop the creative confidence needed to thrive in later life.

Rather than allowing authoritarian, mafia-style management to take over, freedom creates opportunities for all to be empowered and to thrive. In contrast to the controlling bully boss and his weapon of choice, coercion, the guiding or facilitating leader who is able to encourage and bring out the expertise, confidence and creativity in others is increasingly valued.

Rescue strategy 1: cultivate curiosity

The important and difficult job is never to find the right answers, it is to find the right question.

Peter Drucker3

The terminal at Denpasar International Airport in Bali is an unusual architectural building, and sadly we are not using the word ‘unusual’ here in a positive way. The airport sits at the northern end of Jimbaran Bay, just far enough away from the smoky seafood cafes, the runway jutting out between two crystal-clear blue lagoons with white sandy beaches. A single small wire fence separates the famous rolling surf of tourist hotspot Kuta on one side and the quieter cove of Jimbaran on the other. Most of Bali’s 2.75 million tourists pass through this airport twice — either looking forward to their tropical beach holiday or looking back fondly on memories of their experiences. It’s a beautiful waterfront setting. The roof (if you could get to it) would offer 360-degree views of the spectacular island beach vistas. There’s just one big problem, though: the long queues and interminable waits (up to three hours) see travellers locked in a rather dull room with bright lights and expensive shops, and almost no chance of enjoying the major assets of the site. Apart from a few small windows that look out onto the runway tarmac rather than the open panorama on either side of it, the airport is completely walled in. The architect evidently failed to ask questions that would have produced creative solutions on how to take advantage of this prime location.

When architects design buildings, says former architect Lloyd Irwin, first they need to go to the site and ask questions to open up its creative possibilities. Questions should include:

• What is special about this site?

• What does the site need/cry out for?

• What response does it demand from me/the building?

It seems unlikely that the Denpasar airport architects asked these questions when designing their building.

The architect of the famous Sydney Opera House won an international competition launched in 1955 because he answered these questions most completely. To Jørn Utzon, the site was saying two things that produced revolutionary creativity:

• Sails. The waterfront location, great weather and popularity of sailing on the harbour inspired this symbol.

• The fifth elevation. Given the city-front location, Utzon was aware that the building would be viewed from above (from skyscrapers) as much as from the side, so he used the term ‘fifth elevation’ to describe the view of the roof, which needed to be as beautiful as the other four elevations.

Answering questions of design, location and purpose led to the famous sails solution — and an iconic building of creative genius.

The brain is innately creative and curious. Illusions work only because the brain will fill in the gaps to ‘create’ reality. It is up to us to unlock this capability, and the best way to do so is through learning to ask questions. A questioning mind stimulates curiosity, and curiosity fosters the desire to make new discoveries. The creative process can be triggered only by an insatiable appetite to explore and discover — an open and innocent curiosity. But this first step in the creative development process is often hampered by the inability to get past established assumptions and practices.

Geoffrey West (whom we encountered earlier in relation to his work on innovation in cities) spent most of his career studying high-energy physics, grappling with concepts such as quarks, dark matter and string theory. He started to get interested in the application of physical principles to the biological and social sciences around 15 years ago, and he was able to introduce some fascinating new concepts through asking critical questions such as: Why is it that human beings live around the order of a hundred years? Why don’t they live a thousand years, ten years or a million years? Where does that number come from? What is the mechanism of aging?4 Asking questions such as these opened up a whole range of new possibilities. This first step of cultivating curiosity is essential because we usually don’t see the world we live in as it actually is, but rather as we think it is. We see reality based on a set of:

• assumptions

• beliefs

• experiences

• prejudices.

These constitute our worldview, colouring or distorting what we see. Organisations (and societies) tend to have a collective worldview that the majority of its members buy into. To be creative is to see beyond this worldview, and the first significant creative tool is targeted questioning. As George Bernard Shaw famously said, there is a big difference between seeing things as they are and asking ‘Why?’ and dreaming things as they never were and asking ‘What If?” By focusing on how you can disrupt familiar patterns or current systems, you can find completely new and creative solutions.5

Understand: the power of curiosity

Asking good questions is a learned competency based on motivation, know-how and experience.6 We need to learn to ask even ‘dumb’ questions that come from a desire to search for possible solutions, rather than from expectation. If creativity originates with a question, then the art of asking ‘dumb’ questions can lead to enhanced creativity. Sadly, as we move from childhood to adult status we stop asking questions and start wanting to provide answers.

Simply acting based on assumptions can be detrimental to creative problem solving. The aviation industry provides an interesting example of how this can happen. On 24 August 2001 an Air Transat flight en route from Toronto to Lisbon in a one-year-old Airbus A330 got into difficulties. A warning light indicated the plane was losing fuel fast. The captain, who knew it was a new plane, assumed it was simply a computer glitch. Later in the flight another warning light indicated a fuel imbalance between the two fuel tanks. The captain opened the crossfeed valve to transfer fuel from the full tank to the empty one, but the empty tank had a hole so the fuel was simply draining out into the air. Suddenly the plane ran out of fuel. Luckily, because of congestion over North America the plane had been rerouted southwards, so that it was now within gliding distance of the Azores, where the pilot guided it to a safe crashlanding without engines. If, however, instead of making assumptions, the pilot had been more curious about the warning lights and had opened himself up to other possibilities, the potentially disastrous incident might have been avoided.

Surveys of more than 3000 executives and 500 other individuals into what has become known as the ‘Innovator’s DNA’ have identified questioning as one of the five key ‘discovery skills’ that separate true innovators from others.7 8

Creativity enables people to:

• Consider different alternatives. Pierre Omidyar (eBay) talks about how at meetings he pushes people to justify themselves by asking curly questions and playing devil’s advocate. Being forced to imagine different alternatives can lead to truly original ideas.9

• Create constraints for thinking and open up imagining. Great questions actively impose constraints on our thinking, which can, curiously, serve as a catalyst for out-of-the-box insights. One of Google’s key principles is ‘Creativity loves constraints’. This includes utilising ‘what if?’ scenarios. Many people spend too much time trying to understand how to make an existing process work better; innovators are more likely to challenge the assumptions behind the process.

Unlock: the potential of curiosity through questioning

Questions put us into a ready-to-learn state of mind by stimulating curiosity. When you pose a question you give your mind a target. Asking questions is a powerful way to tap into your creative talents. They can open up possibilities and if used well can also provide focus and direction for creative problem solving. Open-ended questions force people to think beyond their established beliefs and assumptions. A common problem is that people want to jump straight to the answers without considering what they are really looking for. It’s almost as though they are too afraid to ask the question if they don’t already know the answer — so they don’t ask. The important thing to remember here is that the first step is simply to ask the question; you don’t need all the answers — yet. To ask ‘why?’/ ‘why not?’ and ‘what if’, for example, can get us thinking beyond the immediate apparent restrictions and open up the realm of the possible.

Next time you have an issue that needs to be resolved, first ask who? what? how? why? why not? what if? Perhaps the architects of the Denpasar airport terminal approached the design in purely practical terms — as a processing centre for embarking and disembarking air passengers. No-one provoked them to ask questions beyond this.

When Rembrandt’s famous painting The Nightwatchman was restored and returned to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, the curators performed a simple yet remarkable experiment. They asked visitors to submit questions about the painting. They then prepared answers, and placed the questions and answers on the wall outside the room in which the painting was displayed. As a result, they discovered, the average length of time that visitors spent viewing the painting increased from 6 minutes to 30 minutes.10 People reported that the questions encouraged them to look longer, look more closely and remember more. Questions can produce dramatic results by:

• giving the mind something to aim for

• putting the mind in a ‘ready to learn’ state

• helping the mind to focus.

Despite undergoing several large-scale renovations and expansions, Bali airport still ignores the view. Perhaps, to make the wait a little less painful, the tourists should be given the opportunity to write a few questions to post to the architects who designed the 2.5/5 rated airport!11

Practise: the technique of questioning

Don’t simply decide: It is not possible for us to become more creative. Go deeper to challenge the assumptions. Ask questions that will open up possibilities, such as:

• Who is affected by a lack of creativity?

• Who should be responsible for bringing creativity into the organisation?

• What difference might creativity make in our workplace?

• What if we were to encourage everyone in the organisation to be a part of the creative development process?

• What can we do to change the status quo and bring in fresh ideas?

• Why consider different options?

• How can creative new ideas and approaches help me/my team?

• How can we take action?

Apply: cultivating curiosity

Next time you have an issue that needs to be resolved ask who? what? how? why? ... For example:

• Who is affected by the issue? Who can take action?

• What are the issues? What can be done to address the issues?

• Why consider different options?

• How can actions make a difference? How can action be taken?

See how creative you can be with solutions!

Rescuer profile 2: courage

This calm affirmer brings back self-belief. Closely related to confidence, courage helps to deal with fear and neutralise ‘fight, flight or freeze’ responses to fear. The rescuer creates a positive linguistic environment that allows creative ideas to flow, and a positive emotional state that encourages the launching of daring quests. With no interest in limiting ideas and options to ‘black’ and ‘white’, but instead readily accepting many shades of grey, courage stimulates new options and possibilities. Courage’s preferred rescue strategy is to accept ambiguity. It rescues from fear murderers such as fear of failure, fear of risk and fear of the unknown, whose weapon of choice is drowning dread.

Have you ever wondered why people like to get tattoos? It is believed that tattoos were originally a way for men to demonstrate their capacity to face fear. Such capacity would have given them an evolutionary advantage, as breeding females would have favoured a mate who was strong and bold enough to protect them. Having a tattoo carved into your body with stone or shell would have been a painful and potentially dangerous undertaking. It demonstrated both a tolerance to pain and physical health, so tattooed people were advertising their prowess and vigour.

Similar signals of courage and vitality are seen in the animal kingdom. In many species, adults will form a defensive circle to protect their young from stronger predators. Gazelles will often leap into the air when escaping from lions. The peacock must carry around that ridiculously large tail simply to impress a potential mate.12

Rather than such exhibitionist expressions, the kind of courage that helps to save creative thinking is an affirming self-belief that challenges and neutralises fear. Consider again the types of creativity-threatening fear already discussed — fear of the unknown, fear of taking risks and fear of failure. To face the first requires the building of self-belief. The last two fears are in many cases quite understandable. Think about a banking institution, for example, where the wrong decision on a risk could cost the organisation a lot of money — and the individual concerned his or her job! Self-belief alone is not enough in this situation; it will require a combination of self-belief and cautious care.

We’ve worked with some very conservative Swiss banks over the years, and we usually find in our workshops that creative thinking is one of the last things they want to hear about from us. Being responsible for other people’s money is in the forefront of their minds, and that requires a conservative approach. There were harsh lessons learned during the global financial crisis, the fear of taking risks and the fear of failure among them. The country CEO of one insurance company we have worked with believes that insurance companies need to be very careful when they talk about being creative. ‘Our company has survived for over a hundred years by being conservative, finding systems that work and sticking with them.’ So when introducing creative thinking to a company that depends on conservative reliability you need to tread carefully. Risking failure in this context can be too spectacular.

For Tim Harford, the way to ensure failure is not catastrophic when trying something new is to introduce it on a scale that means failure would be survivable.13 Learn from your mistakes, and by requesting feedback along the way you can monitor the process. Harford believes that in most cases failure is a price worth paying. We don’t expect every lottery ticket to win, but we have to buy one if we want an opportunity to win at all. Research and development is not simply a redistribution of resources, like the lottery. It can generate improvements that make everyone better off in the long run, so it’s an area in which it’s worth taking risks. Statistically, the chances are skewed towards eventual success, since a lot of small failures will often lead to a few considerable successes.14The general manager of the IT company who had refused to acknowledge the value of new ideas failed to recognise that although most ideas would be likely to fail if actually implemented, the one or two ideas that succeeded would make the effort worthwhile. This GM was not prepared to ‘fumble forward’ in a constructive way, and so shut down his team’s creativity in the process.

Many ideas and projects will falter when there is a fear of ambiguity, when fear of the unknown prompts resistance to ideas that do not fit standard expectations. Openness and trust need to be developed in order for creativity to grow.

Individuals report that in ideal school and workplace environments three key qualities stand out15:

• Teachers/leaders respect me.

• Teachers/leaders are friendly, approachable and willing to listen.

• Teachers/leaders encourage me and help me to succeed.

Surveys by the Gallup organisation have also found that the best leaders create an environment in which people feel they can build trust and develop solid relationships. Such an environment provides individuals with the opportunity to take risks with learning and to develop in a safe and accepting context. Rather than being restrained by fear, individuals who have been listened to and accepted develop resilience and are therefore willing to take more risks. They are able to accept ambiguity rather than being afraid of apparent contradiction.

Roosevelt had the courage to lead his nation through a world war despite his considerable disability. He insisted that ‘there is nothing to fear but fear itself’. Inspired by this example of calm confidence, we can surely face the fears that hold back our creativity and let it flourish.

Rescue strategy 2: accept ambiguity

At the end of day one the organisers of the conference we were assisting with were very upset. The day’s keynote speakers had passed each other at changeover time without so much as a nod, one arriving at the podium as the other left. They certainly hadn’t taken the time to discuss the perspective each would offer and to coordinate their approaches. Without realising he was doing so, the second keynote speaker began to pull apart everything the first speaker had said. So the day’s two keynote speakers had completely contradicted each other, and the organisers thought it made them look bad. As it turned out, though, the apparent contradictions had a positive benefit. Instead of just being ‘empty vessels’ waiting to be filled, audience members now had to think through the two opposing approaches for themselves and come to their own conclusions. Imagine having to actually think independently at a conference presentation — heaven forbid!

Encouraging diverse, even opposing, opinions and ideas can help the creative process. Being spoon-fed homogeneous opinions and ideas does little for our creativity. Listening to lectures or attending seminars, many people (victims of a poor education system) simply ‘bank’ the useful information ready to withdraw later if useful. But it’s hard to be creative if there is no reason to be creative — that is, if we don’t see the need to search for new solutions or find new answers.

Paulo Freire argued that reality is an always changing, transitory process with dialogue and critical thinking at its heart.16 Reality is not static, compartmentalised or predictable, even though some education systems may make it seem so. Freire’s key message to educators was to be wary of encouraging the ‘banking’ of information, by which passive learners have preselected, predefined knowledge deposited into their minds. Freire also saw the danger that people’s creativity could be stifled by what he called ‘the Culture of Silence’, in which individuals lose the means to respond critically to the ideas that are forced on them by the dominant culture. An opposing or oppositional response that struggles with ambiguities is, he believed, at the heart of freedom of expression and free thought. For example, research has shown that in the most successful boards (boards that accept the ‘paradoxical pairings ambiguity brings with it’), ‘constructive critical dialogue is the single best indicator of board effectiveness’.17

Research suggests that highly creative adults have usually been raised in families embodying opposites. ‘Parents encouraged uniqueness, yet provided stability. They were highly responsive to kids’ needs, yet challenged kids to develop skills. This resulted in a sort of adaptability: in times of anxiousness, clear rules could reduce chaos — yet when kids were bored, they could seek change, too. The space between anxiety and boredom was where creativity flourished.’18

Understand: the power of ambiguity

The second approach to individual creative development emphasises the need to accept ambiguities and deal with them, rather than seeing issues in terms of simple black and white and closing off all possibilities when it seems there is no clear option. Remember that accepting ambiguities was listed as one of the keys to successful leadership in innovation and a foundation for creative thinking. Ambiguity can relate to an uncertainty about meaning or application. It can be seeing things that aren’t always visible, or even there at all, which can then lead to creative ideas. People like certainty because it’s safe, but accepting ambiguity is all about embracing uncertainty.

Jim Collins believes we should embrace ‘the genius of the and’.19 We must be able to embrace seemingly opposing extremes on a number of dimensions at the same time. This requires an open, innocent mind — and a whole lot of courage to stand up against the fear that kills flexibility.

Creative leaders don’t fear ambiguity; they use courage to learn how to utilise it. The new leadership models are not static but dynamic. The new leader is flexible, adapting readily to rapidly changing needs and demands. Leaders can become limited by their language and lose the ability to approach and resolve important issues creatively. The secret is learning to embrace ambiguity. Many leaders find this difficult. They think they should lead with strong, decisive, unambiguous decisions, but they fail to recognise that before good decisions can be made all options need to be considered carefully. This requires creative lateral thinking, outside of current language norms. Peter Senge20 believes management teams tend to confront complex, dynamic realities with a language designed for simple problems. It is time, he says, to think and act more creatively as leaders. Creative thinking happens only when people learn to think outside given parameters, when there is a linguistic environment that allows creative ideas to flow.

Unlock: the potential of ambiguity

Few creative ideas are right first time. In fact, innovators have only a 10 per cent chance of starting with the right strategy. What makes the difference in creative organisations is that they start anyway, even before all the pieces are in place. In business it is better to be ‘fumbling forward’ creatively than not to be moving at all. If we want to function creatively, it often means complete solutions will be unavailable. For example, where others sat back waiting to be sure, Google moved forward to test and rethink their strategy three times before landing on the successful one that drives their business today. Moving forward with creative ideas before there is full certainty means it will be important to face and deal with ambiguity along the way.

We need to encourage dualistic thinking. The most successful leaders are integrative thinkers — that is, they can hold in their heads two opposing ideas at once and then come up with a new idea that contains elements of each but is superior to both. This is the process of analysis and synthesis (rather than superior strategy or faultless execution). They promote multidimensional, nonlinear relationships. They resolve the tension between opposing ideas by generating new alternatives.21

When the conference organiser told us that having his two keynote speakers disagree on the same topic was the worst thing that had ever happened in his event-organising career, we smiled. In fact, we were impressed that the speakers had had the courage to express opposing ideas, and the audience had been given a chance to think for themselves. Bring on ambiguity!

Practise: the technique of ambiguous thinking

To use ambiguity as a creative tool you must allow for extremes on a number of different dimensions at the same time and learn to synthesise apparently incompatible opposites. Instead of choosing A or B, think of how it might be possible to have A and B — for example:

• purpose and profit

• continuity and change

• freedom and responsibility

• strength and sensitivity

• brains and brawn

• drive and empathy

• cohesion and cognitive conflict

• trust and distrust

• independence and involvement

• distance and closeness

• creativity and criticality.

Try this exercise: You are driving along in your car on a wild, stormy night. You pass a bus stop, and you see three people waiting for the bus:

• an old lady who looks as though she is about to die

• an old friend who once saved your life

• the perfect man or woman you have been dreaming about.

Which one would you choose to offer a ride to, knowing you could take only one passenger? You could pick up the old lady because she is closest to death, and thus you could be confident of saving her life. Or you could take your old friend because you owe him and this would be the perfect chance to pay him back. Then again, you might never find your perfect dream lover again…

Apply: to accept ambiguity

Think of two issues that seem to have only either/or solutions and come up with creative ways to allow for both possibilities. The moral dilemma above was actually once used as part of a job application. The successful candidate who was hired (out of 200 applicants) had no trouble coming up with his solution: ‘I would give the car keys to my old friend and let him take the old lady to the hospital. Then I would stay behind and wait for the bus with the woman of my dreams.’ This answer illustrates how it is possible to come up with creative solutions when ambiguities are accepted and possibilities are not closed off.

Stage 2: initiation — the independence and openness to let go and grow

The second stage of the rescue process involves release from pressure and expectation and opening up to growth. It includes independence, which frees up the mind to anticipate numerous possibilities, and openness, which ensures different perspectives are considered.

Rescuer profile 3: independence

This imaginative liberator offers an objective view of any situation. Independence provides the opportunity for a calmer, non-emotive reflection on thoughts and actions. Independence has a free will that enables it to open up to any number of possibilities without restriction or judgement. It also brings perspective on who really has control by being able to shut out the many high-pressure murderers. Independence’s preferred rescue strategy is to unleash the imagination. It rescues from pressure murderers excess stress, multi-tasking and expectations, whose weapon of choice is strangling stress.

One of the ultimate tests of courage is the courage needed when facing pressure. In these situations you need to remember that you have free choice, and you can call on Independence to help you through. No matter how powerless or trapped we may feel by pressure, we actually have the means to decide that enough is enough. The insatiable appetite for more and more stress in contemporary life needs to be challenged and confronted head on. Independence enables individuals to recognise the strangling bonds that have held them back and to find ways to release these. It provides an objective view of the situation and gives the opportunity for calm reflection on thoughts and actions.

The first step Independence needs to take is away from constant ‘busy-ness’ and towards taking ‘time out’. Time out can help give perspective, so you can more easily set priorities, assessing which expectations are realistic and which unrealistic. It will also provide the physical, mental and emotional break your body desperately needs. This helps to establish the foundations for learning and creating. An unexpected win to taking time out is that it involves an ambiguity: you can take time out and arrive at innovative solutions. This happens because when we take a break from a situation, our brains often keep working on problems through non-conscious processing. Everyone has had the experience of leaving work with a pressing issue unresolved, only to be overtaken by an ‘a-ha!’ moment during the night, when no longer thinking about the problem. This is the result of non-conscious processing.

What’s even more interesting is that it appears that highly creative people are able to utilise non-conscious processing of innovative ideas more than others, and this is what distinguishes them from the pack. Dr Jason found that after a break people came up with more divergent solutions than when working continuously on a problem, and also, in a related experiment, that highly creative people utilise this non-conscious processing time more effectively than others do. A moment’s reflection makes it clear that we are consciously aware of only so much at any one time, yet we are able to do many things automatically. For instance, you can drive a car and hold a conversation with a passenger at the same time. So when you are really focused on a work problem, what is happening with the parts of your brain that encode emotion, abstract thinking and visual imagery, for example? Brain scans show they are still active, and in a lot of respects they are doing what they always do; they simply don’t have access to your conscious awareness. The bottom line here is that these areas can be called upon to generate diverse ways of thinking about any situation in order to come up with innovative solutions.

Experiments using brainwave scans have measured new neural activity when a rat is exposed to a new situation. When the rat is allowed some down time following this, it is possible to see the new neurons become stimulated through the brain from the hippocampus, which is the brain’s memory access point. This establishes a clear basis for learning. If, on the other hand, you don’t have down time, there will be a neurological toll, and the damage sustained will significantly reduce your ability to think creatively and learn through the process. Imagine how bad it must be for our brains if we continue to challenge our minds through constant simultaneous stimuli, such as when we are consciously multi-tasking. Instead of taking time out, we tend to ‘push through’ the work we need to do relentlessly, no matter how tired we might be or how strained our poor brain is. Perhaps we eventually allow ourselves some time off or have a few quiet moments in the day (sitting at a bus stop or walking to work, say). But instead of spending these quiet times simply enjoying the moment, allowing our minds to wander or constructively meditating, we often continue to fill them up with mind-straining activities, such as texting, tweeting, net surfing or gaming. By doing so we are simply not giving our minds the space they need to be creative. Researchers are now beginning studies to see what effect constant technology use is having on creativity and the imagination in upcoming generations.

Innovation consulting firm Brighthouse actively provides its employees with opportunities to think independently and therefore open themselves up to creativity.22 On top of their regular five weeks’ vacation a year, they are all given an additional five days (called ‘Your Days’) to be devoted to free thinking. Similarly, at the marketing and product development consulting firm Maddock Douglas, employees can bank up to 200 hours a year for pursuing personal interest projects.23

You may still have pressure in your work or life; in fact, as mentioned earlier, many people are more creative under pressure, and perhaps that is something that works well for you, but you need to feel in control of it. You need to feel that it is your choice, that the pressure is not externally imposed. That is why independence is so important in dealing with the potential threat of pressure. Within the confines of their regular restrictions and expectations, everyone has a certain amount of choice. For example, are you staying up late to finish a project because you have been told to do so or because you have not organised your time well enough to get it done in normal hours? Should you be blaming someone or something else for the stress you are feeling, or should you be working to develop better coping mechanisms yourself?

To minimise pressure it is important to ensure there is time when there are no deadlines, expectations and commitments. Through thought management and the daily practice of relaxation techniques, it is also possible to face stressors without feeling the stress. After all, lion tamers manage to remain calm when working with lions! By minimising pressure you can encourage independence, activate free, unrestricted thought and unleash the imagination. This is as true for the organisation as for the individual; an organisation that is always stressed, under pressure and behind schedule is extremely constrained in its ability to move forward creatively.

Rescue strategy 3: unleash your imagination

Do you remember the time when travelling used to provide the opportunity to switch off? When you could use this time to dream of the future, to plan a special event or to solve problems in your mind, or even — heaven forbid! — to unwind and relax? Where travelling time used to be unstructured and unfocused, providing opportunities for free thinking, it is now most often used for completing personal and work commitments. How often have you seen people on public transport texting or calling their friends to make social arrangements or using their iPhone or Blackberry to do web research, send emails or make business calls? How often have you seen people on aeroplanes using their laptops to prepare PowerPoint presentations or write business plans? How often have you done any of these yourself? It’s a great use of otherwise ‘wasted’ down time, but it can come at the expense of unleashing your imagination.

These days most people’s time is strictly scheduled and structured so there is very little left over for ‘free thinking’, the sort of thinking that encourages creative ideas. ‘Free thinking’ time allows the mind to wander into new territories and stumble on new ideas (utilising all the different areas of the brain when the mind is not specifically focused). We have developed the mistaken belief that the more time we spend on focused work activities, the more productive we are being, yet sometimes it is only when we switch off that our mind is really free to be creative. Every day, according to de Bono,24 we should set up ‘Purposeful Opportunities — or ‘POs’ to enable us to let our minds wander. This should be part of our daily routine. Note the famous Google strategy: each employee has one day per week to play with new gadgets/ideas.

Imagination works only in the divergent space in our mind. We know intuitively that down time stimulates creativity: when we suggest that someone ‘sleep on it’ to help them arrive at a solution, we are allowing their divergent thinking to work and giving their imagination room to breathe. This increases the total space in their brain that is open to new ideas.

Understand: the power of imagination

When do your best, most creative ideas come to you? Common answers are in the shower or just as you are waking up or drifting off to sleep. That’s because your mind is at its most divergent and least focused in these moments.25

What did the following people have in common?

• Manfred Eigen, Nobel Prize winner in chemistry (1967)

• Donald Campbell, recipient of Scientific Contribution Award from American Psychological Association (1970)

• Freeman Dyson, recipient of Max Planck Medal (1969) — quantum electrodynamics

• Kekulé, nineteenth-century chemist — molecular structure of benzene

• Archimedes — weight in water theory.

Answer: not one was actively working on his ‘discovery’ at the time of his breakthrough.26 Divergent thinking is a major key to creativity. It is the ability to let your mind wander, to go where it has never been before, to dream. When you allow your mind to wander, you utilise your most powerful creative tool, your imagination. As Albert Einstein said, ‘Your imagination is a preview of life’s coming attractions’.

Remember, 98 per cent of children aged three to five years score at the top of the scale for divergent thinking, while only 2 per cent of adults have similar scores.27 We tend to lose this capacity with formal education and acculturation, yet divergent thinking plays an essential role in helping us to solve problems creatively.

Unlock: imagination techniques

It is possible to develop your imagination by trialling exercises designed to stretch your mind into exploring a range of possibilities.

The Rorschach inkblot test has been used for around 90 years to help people to explore different ideas and interpretations and supposedly reveal their unconscious desires and motivations. Imaginative ideas don’t always have to generate breakthroughs; incremental creativity can be just as productive and frequently more successful.

Mind mapping28 is an exercise to find connections and generate ideas for problem solving. Try this simple mind mapping exercise to see where it leads you: Write the key word ‘happiness’ in the middle of a sheet of paper, and draw lines radiating out from that word. Write down your thoughts on what the concept means to you. Continue to follow as many different concepts as you can, radiating out from the central concept.

Now a business application: Write the central question or ambiguous issue to be resolved (for example, ‘How can a premium product be sold without discounting?’). Develop into a mind map (for example, look at packaging, changing customer habits, changing product, service, production. Think about where, how, whom to sell it to (for example, only in cities). Are there any ambiguities that can be mapped?

Practise: imagination techniques

• Try seeing shapes in the clouds.

• Think of 101 uses for a billiard ball.

• Come up with different interpretations for words in the dictionary.

• Find funny new explanations for typical kids’ questions (for example, ‘Where do fairies come from?’ ‘What makes an aeroplane fly?’ ‘Why is there lightning and thunder in a storm?’)

• Make a symmetrical shape by putting paint in the centre of a page and then fold the paper in half, as in the Rorschach test, and come up with at least five different interpretations for what it could be.

Apply: unleashing the imagination

When you have a problem or issue to be resolved, ask yourself ‘what if?’ questions. Use your imagination to come up with wild and crazy ideas. Sometimes the best solutions can be prompted by the most improbable ideas, as your mind opens up to a new range of possibilities.

Rescuer profile 4: openness

This receptive initiator releases creative thinking. Openness enables the individual to make sense of diverse and often opposing ideas. Openness sees value in everyone and considers every option or idea. Some of the most profound ideas openness accepts don’t come from the ‘experts’, although they should be listened to as well. Through not staying limited to preferred thinking styles but instead accessing all possible approaches, openness creates vast opportunities. The preferred rescue strategy adopted by openness is to access all parts of the brain. Openness saves us from insulation murderers such as biased media, homogeneity and lack of diversity, whose weapon of choice is bludgeoning bias.

Restricting your exposure to information sources can definitely be a problem when it comes to innovation, and can lead to unhealthy insulation. But although we have already identified the media as a clear creativity murder suspect, we need to apply our second creative thinking strategy here — we need to be prepared to accept ambiguity. The media itself is inherently neither positive nor negative. Depending on how it is used, it can in fact be either a murderer or a resuscitator. Like fire, which when controlled can contribute positively to our lives, but when not controlled can be incredibly destructive, the media has the potential to both harm and help.

Of course not all TV shows are dumbing us down. Some shows, for example, require the viewer to make sense of multi-threading, ambiguous themes that encourage creativity to develop.29 (Multi-threading is a term used in computer science to refer to the ability of computers to process multiple sources of input at once and should not be confused with multi-tasking, which usually shuts creativity down.) Some of the complex plots of breakthrough mini-series, which often have numerous characters engaged in different storylines and facing different problems, can make it challenging to piece together the narrative. Shows such as 24, Heroes and Fringe took us across different time zones and into parallel universes; one episode of Heroes followed more than 20 main characters in three time zones, making it a real creative stretch to be able to make sense of it all, let alone find solutions! Also, while TV comedy was traditionally based on a 30-second set-up line before the punchline, in shows such as The Simpsons the jokes work on a number of different levels, with new subtleties of humour becoming apparent only after a few viewings.

There is a difference between intelligent shows and shows that force the watcher to be intelligent. When the intellectual activity takes place only on the other side of the screen, there is no need for the viewer to be creative. It is no more challenging for your mind to watch intelligent shows than it is challenging for the body to watch football on TV — unless you respond to it and act on it. But when the watcher is forced to fill in the details and call on demanding cognitive brain power, creative thinking has the opportunity to thrive.30

When you play chess or Monopoly there is no ambiguity in the rules or the progression from beginner to advanced. In fact, in most games if the rules were ambiguous there would be a fatal flaw in the game. In many video games, however, the rules are rarely established upfront and become apparent only as you play deeper. Many people think video games are only good for developing hand/eye coordination, but the ultimate key to success in video games lies in deciphering the rules and probing the complex physics of a world as a scientist might. Scientific methods need to be applied in assessing probability risk, pattern recognition, participatory thinking and analysis. Reality shows also use a device that’s important in video games: again, the rules are not established. Through probing the system’s rules for weak spots and opportunities, the viewer is encouraged to think through different options to different potential outcomes. When solving puzzles, detecting patterns or unpacking a complex narrative system, the brain is exercised.31

Beyond the media, there are plenty of other opportunities to open up to creative thinking. It is important to know how to access all areas of the brain, to break out of the single-track thinking imposed by insulation, and to be open to opportunities other than those to which the brain is naturally predisposed.

It has been known for some time now that each hemisphere of the human brain has different dominant roles. According to the ‘split brain theory’,32 which was originally popularised more than 35 years ago, the two hemispheres of the brain have two distinctly different functions. While the left brain is dominant for speech and language, ultimately also focusing on logical and detailed tasks, the right brain is responsible for visual and motor tasks. The researchers discovered this specialisation when they severed the corpus callosum (the thick cord of neurons connecting the two distinct halves of the brain) of patients seeking relief from epilepsy. The concept has more recently become so common that people are being labelled ‘left-brain’ thinkers and ‘right-brain’ thinkers according to which hemisphere is thought to be dominant.

However, neuroscience has not emphatically demarcated functions to either the left or the right. The brain is so holistic and so complicated that it is difficult to trim it down to such a simplistic principle. To help keep the concept straightforward and practical, then, we will merely discuss the brain as having a binary function; to go any further than this would be to make the discussion too complex to serve our purpose. So to keep it simple: some people look at problems purely practically and factually, ignoring imagination and emotion, while others view them from a more imaginative and reflective perspective based on feelings, rejecting logic. (Different areas of the brain specialise in emotion, but they are deeper, and not specifically on the right side.) To address this problem simplistically we have referred to this as ‘left-brain dominance’ and ‘right-brain dominance’, although this idea is now a little outdated.

Interestingly, animals do not have the same hemispheric specialisation but have been found to have the same capacities in roughly equal amounts in both sides on the brain. (Dolphins never sleep because they are able to rest one side of the brain while using the other, alternating between the two sides of the brain!) This originally indicated that the lateralisation in humans was an evolutionary development, but more recent research has found that lateralisation is a way for the brain to find more space for development. This is demonstrated by the fact that when you drop some functions on one side of the brain and allow the other side of the brain to develop a specialisation, the ability to utilise more functions is enabled.33

These functions are not so location specific that you can have only one ability or the other. The two hemispheres of the brain are connected by several neuron bridges, known as commissures (the largest of which is the corpus collosum). This bridge, along with other, smaller neuron bridges, enables us to synthesise information from both sources, so we are not completely right or left brained. The more we learn to use these bridges the more flexible our mind becomes and the more capable it is of coping with a wide range of tasks.

It has also been shown that because the brain has significant plasticity, although there may be an initial dominance, each hemisphere can be retrained to learn the skills of the other hemisphere. It was found, for example, that someone who had had a stroke that affected the left brain, and had lost the use of speech as a result, learned to speak again with specific training.34

Creative people can, to some degree, master conscious awareness. They can make conscious choices about which brain process they are using, train themselves to direct an issue to be looked at by one and/or another part of the brain, and arrive at both logical and intuitive solutions as a result. Accessing both sides of the brain is about knowing first what your natural brain dominance is and knowing how and when to switch. It’s also about knowing how often you switch compared with the average person. Unconsciously becoming stuck in one hemisphere or the other for very long periods of time can be a symptom of bipolar disorder.

But for many people it is also possible to control the switch rate. Mathematicians need to stay on one side of the brain longer and remain focused, so they switch less, but artists, musicians and dancers learn to switch more quickly.35 Buddhist monks are able to maintain a very slow switch rate through meditation and deliberately remain in the left side of the brain for long periods of time.36 Neuroscientist Jack Pettigrew believes that brain switching speed could determine what we’ll be good at in life. As you might have already noticed, like most that are worthwhile, this skill often takes long practice, but it is also possible that we can train ourselves to control switching.

The final antidote to the impact of potentially murderous Insulation is to ensure diversity within groups. A diverse group of independent individuals is likely to make certain types of decisions and predictions better than individuals or even experts. Diversity ensures that groups are not drawn towards extremes, but rather are able to take in all perspectives and come to a balanced conclusion. ‘The absence of debate and minority opinions is dangerous in a team,’ believes James Surowiecki. ‘Diversity of opinion is the single best guarantee that the group will reap benefits from face to face discussion.’37

As noted in chapter 2, when forming a new software venture at HP, Peter Karolczak began by gaining multiple perspectives, ensuring divergent expertise. Leaders with the ability to select diverse teams have been found to obtain the most creative groups in a scientific environment.38 While many people continue to build like-minded, homogeneous teams, it is important to find structures to support heterogeneous diverse teams that allow for a range of individuals and ideas.

Rescue strategy 4: access all parts of the brain

You know your children are growing up when they stop asking you where they came from and refuse to tell you where they’re going!

P. J. O’Rourke

Having a teenager has its moments. It seems to be a stage in life when kids become incredibly inventive and accomplished at not telling (or at least stretching) the truth. One common trick is for them to say they are sleeping over at a friend’s place, while they are actually up to mischief elsewhere. With each parent assuming that the other is watching over the children, the kids themselves manage to slip under the radar undetected. When asked, ‘What did you get up to last night?’ there are only two real responses teenagers can make: (1) they can tell the truth, or (2) they can lie. When they are telling the truth they are accessing the more factual side of their mind, recalling real events recorded inside their brain. When they are lying, they are actually telling stories. They are making up an event that didn’t happen (or changing the facts), which takes a lot more concentration and imagination. What has been discovered is that storytelling and recalling facts access different parts of the brain, and this offers a clue as to how we can start to revive creative thinking.

A handy secret for parents is that we can now discover when teenagers are telling stories (or, to avoid the euphemism, lying). The TV program Lie to Me popularised psychologist Paul Ekman’s research into body language. The underlying assumption is that when a person is lying they are accessing the right side of their brain (imagination), and their eyes will look upward and to the left to access the relevant part of the brain. Fortunately, carefully checking the eyes of your potentially deceitful teenager the morning after a night out can also help to assess the possible lack of sleep and/or consumption of harmful substances, so it’s in any case a useful exercise.

Dr Jason’s research reminds us also that we can utilise spontaneous processes by giving the brain time to ‘incubate’ and thereby access both emotional and cognitive solutions that may have been previously unavailable to conscious awareness. This can enable us to fully utilise the brain’s capabilities and learn and train creative thinking.39

Understand: the power of accessing all parts of the brain

Accessing all parts of the brain enables effective integration of the following, apparently opposing functions:

• predominantly left-brain functions: logical, sequential, analytical, methodical, focused on details

• predominantly right-brain functions: holistic, synthetic, artistic, emotional, focused on the big picture.

Although most of us are born with the ability to utilise all parts of the brain, and our natural development encourages this process, life experience can stifle the ability. The more we use one part of the brain to solve a problem, the more we tend to use that area again. But it is possible to regain a balance by deliberately exercising the non-dominant parts of your brain.

The term ‘dialectical bootstrapping’40 has been used to describe how we can learn to tap into more perspectives that are already inside our heads. This concept involves the unique idea that each of us has a diverse board of directors in our heads, but that we can only run a good board meeting if we learn to listen to each perspective and incorporate it in our decision making.

We have discussed how in order to be creative you need to be able to balance left-brain functions with right-brain functions, so the outcome of creative thinking that successfully accesses and synthesises both sides of the brain is much deeper and more enriched. The process becomes:

• not just function but design

• not just argument but story

• not just focus but symphony

• not just logic but empathy

• not just seriousness but play

• not just accumulation but meaning.41

Unlock: accessing all parts of the brain

Raise your right hand. Did you know your left brain is controlling this function? Now tap your left foot. This is being controlled by your right brain. Those who predominantly use their left brain will be trying to analyse this information. They will be analysing the details and asking, ‘Is it true? Will it work? How can I prove it/quantify it?’ The right hemisphere of the brain processes information ‘holistically, as a big picture’. Those who predominantly access their right brain will find it easier to accept the imaginative approach.

We must learn to accept and utilise all approaches: to understand the world not only as a set of logical propositions but also as patterns of experience. We all have natural predispositions and preferences — for example, which hand we use to do things. The more we use this hand, the more comfortable we feel using it, but the opposite is also true: the less we use the hand, the less comfortable we feel using it. If you are asked to catch something with one hand, which hand would it be? As we grow, we develop certain muscle coordination and preferences. The same is true with the ways we think, but to be truly creative we must break these patterns and open up to new ways of thinking.

In our seminars, when we ask people to produce mind maps to illustrate a problem, it’s amazing how often their responses are heavily weighted to one hemisphere, usually the left-brain approach. When we explain the importance of being open to looking at both sides for solutions, a whole new set of ideas emerges.

So before you next tuck your teenager into bed for a good night of sleep (hoping they won’t sneak out later), if you’d like to develop their skills at using all parts of the brain, ask them to try cleaning their teeth with their non-dominant hand!

Practise: to access all parts of the brain

By looking at a problem from different angles (dialectical bootstrapping), it is possible to create diversity in thinking. Try using the following method of devising your own mental board of advisers to consult when facing a problem or planning to come up with something new42:

• Assume that your first solutions are off the mark or incomplete.

• Think about a few reasons why that could be so. (Which assumptions and considerations could have been wrong?)

• What do these new considerations imply?

• Based on this new perspective, develop a second, alternative set of solutions.

Mind mapping seeks to use the whole brain to solve a problem or understand an issue. Instead of the usual approaches, which force the mind to think in a logical way, mind mapping incites more creative solutions by ‘cooperating’ with brain structure and physiology through thinking in radial forms — much like the pattern of thoughts as they move across the neurons in the brain — and stimulating both hemispheres equally.

To practise, use colour pens and develop your own symbols, icons and visual vocabulary for your mind maps. Making a list is a left-brain task; the use of colour, visuals and radiating forms are right-brain tasks.

• Write down a work-related issue you would like to address, and list possible solutions from the mind map. Identify which of these are left- and right-brain focused. If you were heavily dominated by one side of the brain, try now to find solutions using the other side of your brain.

• Record a task you had to complete recently at work, and write down how you approached it to determine what your natural orientation is. Now look at how you could use the other side of your brain more by using associated skills.

• Record a question that needs to be answered from the issues that you identified:

• Make a list on the left side of how this task could be approached logically.

• Make a list on the right side of imaginative and more emotional responses.

As a warm-up, practise drawing a symmetrical picture with your left and your right hand at the same time. Next, try to draw a face in profile with your dominant hand, and then draw a mirror image of that face with the other hand.

To improve left-brain performance, try:

• mathematical puzzles

• word definition exercises

• magic squares.

To improve right-brain performance, try:

• creative writing

• letter and word puzzles

• spatial awareness games.

Apply: accessing all parts of the brain

At the top of a piece of paper write down a task you need to complete. Divide the page into two columns, and list how you could approach the task from a logical, ‘left-brain’ perspective in the left column and a more imaginative and feeling-based, ‘right-brain’ perspective in the right column.

Stage 3: motivation — the passion to drive transformation

The third stage of the regenerative rescue process treats apathy and ensures there is inspiration for continued growth. This stage focuses on passion, which is not content with conservative and standard ways of thinking, but rather continues to push the boundaries with new ideas and concepts born from a deeper commitment.

Rescuer profile 5: passion

This zealous motivator understands the importance of the labour of love. Passion recognises that the most successful people often are not the most talented but the ones who are impelled by innate curiosity. Passion is not satisfied with accepting or conforming to the way things are, but instead is prepared to break apart the old in order to make way for creative new connections. Its healing power and intrinsic motivation helps to restore self-belief and confidence and drive towards outstanding outcomes. Passion’s preferred resuscitation strategy is to reconstruct common concepts. It offers rescue from apathy murderers such as lack of motivation, lack of initiative and lack of drive, whose weapon of choice is lacerating lethargy.

Vikki Howorth is someone who exemplifies the creativity that can come from a focused passion. She is a woman on a mission. After building a successful PR business with her husband Mike, she now has the opportunity and financial independence to devote her time and energy to making a difference in others’ lives. She uses her experience to increase awareness of global poverty issues, and she has a targeted strategy. She is a supporter of the ‘Micah Challenge’,43 which has established specific steps for helping to ensure politicians remain accountable for working towards the UN’s ‘Millennium Development Goals’. These are eight international development objectives that all 193 United Nations member states and at least 23 international organisations have agreed to achieve by the year 2015. In these goals, governments have promised to reduce poverty in specific ways — for example, by reducing the child mortality rates, eradicating extreme poverty, fighting global disease epidemics such as AIDS, and developing global partnerships for development. It is an ambitious venture, but one that is so goal oriented and practical that it really could make a difference.

What strikes you when you meet Vikki is her exuberance and enthusiasm for the task at hand, and her perseverance in following through to get the job done. Determined not to give up and to continue to be a ‘voice for the voiceless’, she is proud of the fact that she has been labelled ‘the loudest nagger’ on behalf of the poor by her local federal government member. She travels to Canberra to lobby politicians, bringing clever artistic expressions of community commitment to the Millennium Development Goals. In partnership with a creative team from her Christian community, who are just as passionate as she is, Vikki has previously been involved in such projects as presenting larger-than-life-sized pictures of politicians with notes from children urging them to continue to support the Millennium Development Goals. To address the global midwife crisis, she presented a ‘Special Delivery’ to our foreign affairs minister — a jacket adorned with cards of ‘hope’ — that read ‘our hopes are pinned on you’. And she persuaded politicians to sit on a giant toilet on the Parliament lawn to draw attention to global sanitation issues. Along with Mike and her family, she has also spent time on the ground in the countries she supports. Through her church she works with Compassion Australia, also committed to following through on the Millennium Development Goals. A highlight of their fundraising activities is a fundraising walk, which raises up to $50 000 at a time from sponsorship of just a small number of walkers. The walk confronts participants with challenges faced in developing countries — for example, they are asked to carry buckets of water to represent the distance many people in the world need to walk to get access to drinking water.

When you have a passion, you have a purpose and often become incredibly driven and creative. You have the desire to keep persevering and to follow through. When you have this sort of desire to do something, you devote time and energy to it. You don’t simply accept things the way they are; you put in the effort to look at them from a different perspective. Changing the world takes passion; changing a small area in your life takes this sort of passion and commitment too.

Benjamin Bloom, a professor of education at the University of Chicago, found that all the high achievers in his research study had been inspired by keen teachers and supported by devoted parents. And they had all developed a high level of expertise generated from the intense passion that leads to commitment, rather than from having any particular innate skill or talent. Later research building on Bloom’s pioneering work, as compiled in The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, also revealed that high achievers are made, not born. This is an illustration of how passion can also create the conditions for the growth of creativity in others.

Harvard professor Teresa Amabile focuses on motivation in her studies of successful creative thinking because, as she believes, ‘The desire to do something because you find it deeply satisfying and personally challenging inspires the highest levels of creativity, whether it’s in the arts, sciences, or business’.44

Malcolm Gladwell, a writer who has helped to humanise and popularise economics over the past few years, has cleverly calculated the number of hours that any individual needs to put in to become an ‘expert’ in a specific area — 10 000 hours, which adds up to about 10 years in most cases.45 That’s a huge amount of time, and yet he brings up example after example to illustrate how this has consistently been the case with high achievers.

So who would put in these sorts of hours if they didn’t have passion? Yet even with all this practice, there is still a big difference between those who become ‘technical experts’ in a field and those who move beyond what others have done before them. Gladwell points out that Mozart wrote his first completely original masterpieces after the age of 40 — after having built up 10 000 hours of compositional practice (there’s that magic number). Mozart’s passion enabled him not only to produce technically accomplished music, but to utilise his creativity to write music that would engage and inspire others. But don’t mistake our point here. We are not suggesting that you need to put in 10 000 hours of practice to be creative — we are saying passion facilitates creativity. All of these highly creative individuals already had a passion that supercharged their subsequent creative output.46

Think of people who have inspired others through their passion and commitment: Alexander Fleming was not the first physician to notice the mould formed on an exposed culture while studying deadly bacteria. A less gifted physician would have ignored this seemingly irrelevant occurrence, but Fleming found it ‘interesting’, wondered if the process had scientific potential and after further investigation discovered penicillin, which would save millions of lives.

Organisations that have thought simple monetary incentives could motivate creativity or trigger passion have been disappointed. In a study performed in the US, moderate incentives were offered for better performance on creativity tasks; in a similar experiment in India massive incentives (up to several months’ wages) were offered. It turned out that creative performance was actually lower under increased monetary incentives. What, then, does incentivise people to be creative? One of three key factors appears to be autonomy, which stimulates a personal passion and pride.47

Like Henning’s discovery of phosphorus, if you don’t take initiative and just ‘get going’ with the creative process you will never get anywhere. Similarly, if you don’t have the drive and perseverance to push the creative process through to a practical outcome, you won’t actually achieve much. Intrinsic motivation is critical here, as unless the motivation is intrinsic the creative passion will not survive. When Arthur Schawlow, winner of a Nobel Prize in physics in 1981, was asked what he thought made the difference between highly creative and less creative scientists he replied, ‘The labor of love aspect is important. The most successful scientists often are not the most talented. But they are the ones who are impelled by curiosity. They’ve got to know what the answer is’.48

Rescue strategy 5: reconstruct common concepts