Contents

Chapter One. Lessons from the Sandbox

Everything we need for today's marketplace we learned as kids.

Chapter Two. Check Your Moral Compass

We know darn well what is right and wrong.

Chapter Three. Play by the Rules

Compete fiercely and fairly—but no cutting in line.

Chapter Four. Setting the Example

Risk, responsibility, reliability— the three Rs of leadership.

It's high time to corral the corporate lawyers.

Chapter Six. Pick Advisors Wisely

Surround yourself with associates who have the courage to say no.

Chapter Seven. Get Mad, Not Even

Revenge is unhealthy and unproductive. Learn to move on.

Chapter Eight. Graciousness Is Next to Godliness

Treat competitors, colleagues, employees, and customers with respect.

Chapter Nine. Your Name Is on the Door

Operate businesses and organizations as if they're family owned.

Chapter Ten. The Obligation to Give Back

Nobody is completely self-made; return the favors and good fortune.

Acceptable moral values are child's play, not rocket science.

TO KAREN,

MY PARTNER AND

BEST FRIEND.

Praise for Winners Never Cheat

"How timely! How needed it is for one of the finest human beings, industrial leaders and philanthropists on the planet to compellingly drill down on 10 timeless, universal values for business and life. This book edifies, inspires, and motivates all of us to model these commonsensical lessons for our organizations, all our relationships and especially our posterity-for what is common sense is obviously not common practice.

Primary greatness is character and contribution. Secondary greatness is how most people define success-wealth, fame, position, etc. Few have both. Jon's one of them."

—Dr. Stephen R. Covey, author, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People and The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness

"In his creative gifts, in his business success, in his great philanthropy, in his human qualities, Jon Huntsman stands in a class all of his own."

—Richard Cheney, Vice President of the United States, on the occasion of the dedication of Huntsman Hall, The Wharton School, The University of Pennsylvania

"Jon Huntsman has successfully navigated corporate America guided by a strong moral compass. In his book, Jon shares his depth of knowledge and outlines how to succeed in today's competitive market place while taking the high ground."

—Senator Elizabeth Dole

"Jon Huntsman's new book ought to be mandatory reading for leaders—and those who aspire to be leaders—in every field. His secrets for success are no secrets at all, but invaluable lessons that he has reminded us, with his life and now with his words, are the pillars upon which we can build our lives, too."

—Senator Tom Daschle

"Jon Huntsman's book is about ethics, values, and his experiences. The practical way in which he shares those with the reader is amazing. This is a book with inspiration for a younger generation."

—Jeroen van der Veer, Chief Executive, Royal Dutch/Shell Group

"As I read Jon's book, I thought my father had returned to tell me that you are either honest or you are dishonest, that there is nothing in between. 2 + 2 = 4, never 3.999 or 4.001. Also, if you always say what you believe, you don't need to have a good memory. If we could only live the principles Jon has followed, what a different world it would be—both in our business and personal relationships."

—Former U.S. Senator and Astronaut Jake Garn

"Jon Huntsman has taken us back to the basics—the basic values that transcend all professions and cultures. He has provided real-life examples that are inspiring and show that 'good guys'; really can finish first. And he shows us how you can learn from mistakes. It is a 'must read' for both young men and women just stepping onto the golden escalator to success and anyone seeking reassurance that how one lives every day really does matter."

—Marsha J. Evans, President and CEO, American Red Cross

"A refreshing and candid discussion on basic values that can guide you from the sandbox to the board room—told by a straight shooter."

—Chuck Prince, CEO, Citigroup

"Jon's outlook on moral and ethical behavior in business should be inspirational to all who read this book. The lessons of fair play and holding true to personal moral values and ethics are time-honored principals which are all too often overlooked in today's world. While this book is geared to those in business, I see it as worthwhile reading to anyone."

—Rick Majerus, ESPN Basketball Analyst and legendary former basketball coach, The University of Utah

"It is true that all business enterprises are profit oriented, but the avarice for wealth and the ardent desire to stay competitive tend to lure more and more corporate executives to resort to unscrupulous, unethical practices. Although they may achieve temporary successes, their lucrative lies and fraud will be their ultimate undoing, causing great losses to their shareholders. Jon's book is a stentorian call for the corporate world to reassert accepted moral values and learn the responsibility of sharing gains with society, probably in line with the economic standard of the country.

—Jeffrey L.S. Koo, Chairman and CEO, Chinatrust Financial Holding Co.

"Succinctly capturing what the world's major beliefs all hold as an unassailable truth, that ethical behavior and giving more than you receive is the path to fulfillment and success in life, Winners Never Cheat deftly navigates these concepts with clarity and insight."

—Louis Columbus, Director of Business Development, Cincom Systems

"This is easily the most courageous and personal business book since Bill George's Authentic Leadership. If anyone has doubts about how one person can make a substantive difference in the world, this beautifully written book should dispel them immediately. I hope its message is embraced worldwide."

—Charles Decker, Author of Lessons from the Hive: The Buzz for Surviving and Thriving in an Ever-Changing Workplace

"Jon Huntsman and I have this much in common: We were raised to work hard, play fair, keep your word and give back to the community. I relate to what he is saying. Real winners never cheat."

—Karl Malone, Twice MVP of the NBA and Utah Jazz legend

"In an age of corporate scandal and excess, Jon Huntsman reminds us of the enduring value of honesty and respect. He shows us that morality and compassion are essential ingredients to true success. Over the years, Jon's extraordinary business achievements have been matched by a sense of charity that continues to touch countless lives. I am privileged to call him a friend."

—Governor Mitt Romney

"I can't put down the book after reading the first page. These are values universally cherished, whether in the United States, in China or elsewhere. A great and loving man emerges from the pages so vivid that he seems to talk to you face to face, like a family member. My life is richer and mind is broader after reading the book. I am very proud of my friendship with Jon Huntsman."

—Yafei He, Director General, Ministry of Foreign Affairs—China, Dept. of North American and Oceanic Affairs

"Nothing could be more timely than this provocative book from one of America's foremost business and civic leaders about the urgent need for greater ethics in our public and private lives. With wit and clarity, Jon Huntsman shares his guidelines for living a life of integrity and courage. It is a wonderful tonic for much of what ails us today. Winners Never Cheat is a valuable handbook for anyone wanting to succeed in business, or life."

—Andrea Mitchell, NBC News

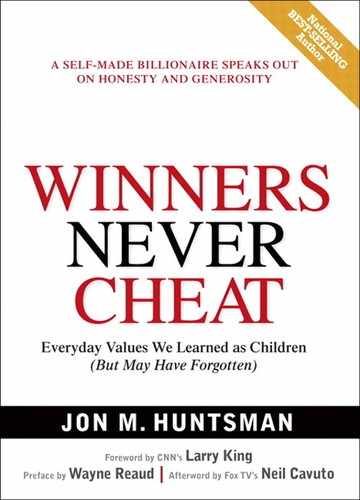

"Jon Huntsman is more than a phenomenally successful entrepreneur. He is a giant of a leader and a role model of integrity. In Winners Never Cheat: Everyday Values We Learned as Children (But May Have Forgotten), Mr. Huntsman establishes the inextric able link between following one's inner moral compass and achieving lasting success. His book is filled with timeless wisdom, timely examples, and an inspiring life story. Jon is the quintessential nice guy who has finished first!"

—Dr. Amy Gutmann, President, University of Pennsylvania

Acknowledgments

I wish to convey my great appreciation to Jay Shelledy, a professional writer and editor, who challenged and organized my thoughts and helped convert them to the written word, and to Pam Bailey, my dedicated and loyal administrative assistant who eased the hassle with those astounding and generally unknown complexities of writing a book.

I also desire to thank deeply the professionals at Pearson Education: editor Tim Moore, senior vice president, sales and marketing, Logan Campbell, and marketing director John Pierce, for their unwavering commitment to and patience with a first-time author; development editor Russ Hall for clear and candid critiques; senior project editor Kristy Hart and copy editor Keith Cline for their swift, quality-enhancing suggestions to and the preparation of my manuscript; and Wharton School administrators, faculty, and students for their longstanding support in this and other endeavors.

I would be especially remiss if I did not acknowledge the contributions of Larry King, whose gracious Foreword set the tone for what follows; of Neil Cavuto, for his kind Afterword and whose own book, More Than Money, provided inspiration; and of trial lawyer extraordinaire Wayne Reaud for his humbling Preface. They are more than just successful professionals, highly respected by their peers; they are friends of mine.

I am indebted to my mother and other family members—living and deceased—for providing models of kindness and decency, and to my late father-in-law, David Haight, who always believed in me.

My greatest debt, however, is reserved for my spouse, Karen, our 9 children, and 52 grandchildren for providing me with 62 convincing reasons why a person ought to stay the proper course.

—J.M.H.

About the Author

Jon M. Huntsman is chairman and founder of Huntsman Corporation. He started the firm with his brother Blaine in 1970. By 2000, it had become the world's largest privately held chemical company and America's biggest family-owned and operated business, with more than $12 billion in annual revenues currently. He took the business public in early 2005. He was a special assistant to the president in the Nixon White House, was the first American to own controlling interest of a business in the former Soviet Union, and is the chairman of the Board of Overseers for Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater. Mr. Huntsman also has served on the boards of numerous major public corporations and philanthropic organizations, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the American Red Cross. The Huntsman businesses fund the foundation that is the primary underwriter for the Huntsman Cancer Institute, which he founded. It has become a leader in the prevention, early diagnosis, and humane treatment of cancer. He resides with his wife, Karen, in Salt Lake City. His oldest son, Jon Jr., was elected governor of Utah in November 2004.

Preface

I'm a trial lawyer and the book you're about to read could put me out of business. Nobody would be happier about it than me.

Over the past 30 years, I have taken some of America's biggest corporations to court, calling them to task for behavior that threatened people's health and livelihoods. From asbestos makers to tobacco purveyors to computer manufacturers, I have fought to make big companies more accountable in their business dealings.

Ordinarily, you would not expect a trial lawyer to be particularly close with the CEO of a big corporation. So when people hear that Jon Huntsman and I are good friends, and have been for 15 years, they tend to scratch their heads. In the ecology of the business world, aren't we natural enemies? Don't our respective jobs put us at odds with each other? The answer to both questions is no. And the reason is simple: Jon Huntsman is not your average CEO.

Jon is a true rarity in the corporate world: a hugely successful entrepreneur whose conscience is as sharp as his business sense, whose word is known as an unbreakable bond. From his very first job, picking potatoes in rural Idaho at age eight, to his current position of running the world's largest private chemical company, he has always put ethical concerns on equal, if not greater, footing than his business concerns.

I could give you a laundry list of things Jon has done—donating record-setting amounts to cancer treatment and research, tithing to his church, giving millions to colleges and universities—but that still wouldn't give you a clear idea of why he's so unusual. His ethics go far deeper than simply making donations and glad-handing for good causes. They are at the core of his being. They are, for him, a way of life.

In Plato's seminal work, The Republic, he gives us the notion of the ideal leader: the "philosopher-king." This is the man who possesses the perfect marriage of a philosophic mind and an ability to lead. As Plato wrote: "I need no longer hesitate to say that we must make our guardians philosophers. The necessary combination of qualities is extremely rare. Our test must be thorough, for the soul must be trained up by the pursuit of all kinds of knowledge to the capacity for the pursuit of the highest—higher than justice and wisdom—the idea of the good."

Jon Huntsman has pursued "the idea of the good" all his life, and as the continued health of his companies show, he's more than able to lead. But the true test of ethics comes not when a person gives with nothing to lose. It comes when he gives with everything to lose. That's why Jon Huntsman is the right man to do this book. And there's no question that he's doing it at just the right time. In this age of Enron, Tyco, insider-trading scandals, and rampant corporate malfeasance, we need Jon Huntsman's voice and leadership more than ever.

I hope Jon's book will remind us all that, like him, you can do well and do good at the same time. As a trial lawyer, I want every businessperson in America to read this book and take to heart Jon's example. Maybe then my fellow trial lawyers and I would have nothing left to do.

There's nothing I'd like better.

—Wayne Reaud

Foreword

Jon Meade Huntsman may well be the most remarkable billionaire most of America has never heard of. Legendary in petrochemical circles, he operates around the globe in a quiet, determined, respected, and caring manner. For nearly two decades, he found himself in the upper tier of Forbes magazine's list of wealthiest Americans, but it wasn't always that way.

Jon is the embodiment of the American Dream. His was a journey from hardscrabble beginnings to chairman of America's largest family-owned and-operated business. (In early 2005, he took the sprawling Huntsman empire public.)

As is the case with each Horatio Alger character, Jon Huntsman was afforded nothing but an opportunity to compete on the field of dreams. The rest—vision, determination, skill, integrity, a few breaks, and ultimate success—was up to him.

He won that incredible race fair and square, fulfilling his dream with moral principles intact, his word being kept, dealing above board and fairly with colleagues and competitors alike, and displaying a demeanor of decency and generosity.

All this, to me, is the essence of Jon Huntsman. It is why he has written this book and why it is worth your time to read it.

His career was launched with an undergraduate degree from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, an education made possible by a chance scholarship from someone who already had it made. Jon went on to build an empire and render an accounting for the favors and breaks he received along the way.

You may not have heard of Jon Huntsman, but the folks he has assisted over the years sure have.

Ask patients at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Hospital, a world-class research and patient facility in Salt Lake City exploring how we might prevent and control the dreaded disease, especially hereditary cancers. The Huntsman family has given a quarter of a billion dollars so far to that effort and vows to double that amount in the coming years. Jon lost his mother, father, stepmother, and grandparents to the disease. He himself has had cancer and beaten it. Twice.

Ask students and faculty at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where he became chairman of the Board of Overseers. His gift of $50 million made possible Huntsman Hall, a state-of-the-art business school complex, and the nation's leading international undergraduate program. Remembering what the chance for a college education meant to him, he has awarded several million dollars in scholarships over the years to employees' children and random students.

Ask the people of Armenia. Now there's a story worth telling.

On the evening of December 7, 1988, Jon and Karen Huntsman were watching the news in the living room of their striking Salt Lake City home. He was chief executive officer and chairman of Huntsman Chemical Corporation—an upstart in the stodgy and traditional chemical industry.

The lead story that nightly news was unsettling: An earthquake had devastated much of Armenia. Jon was riveted by the scenes of destruction unfolding before him: factories and apartments in rubble, roads and railways little more than twisted pretzels of concrete and steel, school buildings flattened, frantic survivors clawing through debris for loved ones.

A year earlier, Jon Huntsman probably could not have located Armenia on the map, but in the six previous months he had negotiated with Aeroflot, the airline of the old Soviet government, to manufacture in a new Moscow plant plastic service ware for in-flight meals. In the process, he became the first American permitted to own a majority interest in a Soviet business. He had become fascinated with the USSR bear, and now disaster had struck one of its satellite states.

"We have to do something," he said to Karen that night. He was taking the suffering before him personally. That's how Jon Huntsman is.

The aid that followed ranged from expertise and resources for a modern cement factory that would produce concrete that could withstand most quakes to food and medical equipment to apartment complexes and schools—all as gifts to a grateful, battered nation.

Before he was finished 15 years later, the Huntsman family had infused $50 million of its money into Armenia, visiting the nation two dozen times. Yet, on that December 1988 night, he had no ties to that region of the world. He didn't know the name of a single victim. But the name Huntsman is not unknown in Armenia today, where Jon is an honorary citizen and recipient of the nation's highest award.

Who is Jon Huntsman? Ask those who have been helped. Ask the communities around the globe where Huntsman Corp. does business. They will tell of the deep, personal interest he has in their fortunes, their families, and their futures.

Perhaps that generosity is the residual of growing up on the other side of the economic tracks. If so, it is only part of his philanthropic equation. Jon also subscribes to the obligation of everyone to be generous. Throughout the ages, charity has been a cornerstone of most world cultures.

The Gospel of Giving according to Jon holds that every individual—whether financially stretched or of means, but especially the rich—is duty-bound to return a portion of his or her blessings.

Jon Huntsman is a different breed. He believes business is a creative endeavor, similar to a theater production, wherein integrity must be the central character. Notwithstanding what you hear on the nightly news or read in newspapers, decent, ethical behavior is not a moral heirloom of the past. He believes in being honest, fair, and gracious—even when it costs him several million dollars.

This book isn't simply a marketplace catechism for moral behavior. In every chapter, there are nuggets of good management techniques for those who run companies or organizations, solid instructions for those in mid-management, and a bigger picture for employees and memberships. With an MBA from the University of Southern California, Jon is not only an entrepreneur extraordinaire but also an experienced CEO who has seen it all.

For the past 35 years, his business has gone from scratch to annual revenues of $12 billion. It wasn't all smooth sailing. He was on the verge of bankruptcy twice, but his reputation for tough-but-fair negotiations, a gracious and sensitive demeanor, an entrepreneurial sense, and a remarkable philanthropic commitment give him a unique perspective from which to offer these rules of the road.

Jon Huntsman is living proof you can do well by doing right. Leo Durocher was quite wrong when he said, "Nice guys finish last." Not only can nice people finish first, they finish better. Jon has little patience for situational ethics in the marketplace or life. He paints proper behavior in bold, black-and-white strokes. He believes in the adage that if you have one clock, everyone knows what time it is. If there are two, no one knows the time.

In 2002, I named him the Humanitarian of the Year because of his generosity to others. (Business Week ranks him among America's top philanthropists.) He even surprised me with a large, unexpected contribution to the Larry King Cardiac Foundation to help those who suffer from heart disease. My spouse, Shawn, and I count ourselves fortunate to have been friends of the Huntsman family for many years. I enthusiastically introduce Jon and recommend his take on life to you.

You'll get into Winners Never Cheat.

—Larry King

Chapter One. Lessons from the Sandbox

Everything we need for today's marketplace we learned as kids.

IF THE GAME RUNS SOMETIMES AGAINST US AT HOME, WE MUST HAVE PATIENCE TILL LUCK TURNS, AND THEN WE SHALL HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY OF WINNING BACK THE PRINCIPLES WE HAVE LOST, FOR THIS IS A GAME WHERE PRINCIPLES ARE AT STAKE.

—THOMAS JEFFERSON

COMMERCE WITHOUT MORALITY.

—THE FOURTH OF GANDHI'S SEVEN SINS

Growing up poor in rural Idaho, I was taught to play by the rules. Be tough, be competitive, give the game all you have—but do it fairly. They were simple values that formed a basis for how families, neighborhoods, and communities behaved. My two brothers and I had something in common with the kids on the upscale side of the tracks: a value system learned in homes, sandboxes, playgrounds, classrooms, Sunday schools, and athletic fields.

Those values have not lost their legitimacy simply because I am now part of the business world, yet they are missing in segments of today's marketplace. Wall Street overdoses on greed. Corporate lawyers make fortunes by manipulating contracts and finding ways out of signed deals. Many CEOs enjoy princely lifestyles even as stakeholders lose their jobs, pensions, benefits, investments, and trust in the American way.

Cooked ledgers, look-the-other-way auditors, kickbacks, flimflams of every sort have burrowed their way in today's corporate climate. Many outside corporate directors bask in perks and fees, concerned only in keeping Wall Street happy and their fees intact.

In the past 20 years, investor greed has become obsessive and a force with which CEOs must deal. Public companies are pushed for higher and higher quarterly performances lest shareholders rebel. Less-than-honest financial reports are tempting when the market penalizes flat performances and candid accounting. Wall Street consistently signals that it is comfortable with the lucrative lie.

Although I focus much of my advice on business-oriented activities, the world I know best, these principles are equally applicable to professionals of all stripes and at all levels, not to mention parents, students, and people of goodwill everywhere.

In the 2004 U.S. presidential election, morality issues influenced more votes than any other factor, but a Zogby International poll revealed that the single biggest moral issue in voters' minds was not abortion or same-sex marriage. Greed/materialism far and away was cited as the most urgent moral problem facing America today. (A close second was poverty/economic justice.)

In nearly a half century of engaging in some sort of business enterprise, I have seen it all. I keep asking myself, perhaps naively so, why lying, cheating, misrepresentation, and weaseling on deals have ingrained themselves so deeply in society? Could it be that material success is now viewed to be more virtuous than how one obtains that success?

One might even be tempted to believe that the near-sacred American Dream is unobtainable without resorting to moral mischief and malfeasance. Nonsense. Cutting ethical corners is the antithesis of the American Dream. Each dreamer is provided with an opportunity to participate on a playing field made level by fairness, honor, and integrity.

In spite of its selectivity and flaws, the American Dream remains a uniquely powerful and defining force. The allure stands strong and steady, but never so feverish as in pursuit of material gain. Achieving your dream requires sweat, courage, commitment, talent, integrity, vision, faith, and a few breaks.

The ability to start a business from scratch, the opportunity to lead that company to greatness, the entrepreneurial freedom to bet the farm on a roll of the marketplace dice, the chance to rise from clerk to CEO are the feedstock of America's economic greatness.

The dot-com boom of the 1990s, although ultimately falling victim to hyperventilation, is proof that classrooms, garages, and basement workshops, crammed with doodlings and daydreams, are the petri dishes of the entrepreneurial dream. In many ways, it has never been easier to make money—or to ignore traditional moral values in doing so.

Throughout this nation's history, a spontaneous and unfettered marketplace has produced thundering examples of virtue and vice—not surprising in that very human heroes and villains populate the business landscape. Yet, a new void in values has produced a level of deception, betrayal, and indecency so brazen as to be breathtaking.

Many of today's executives and employees—I would like to think the majority—are not engaged in improper behavior. Most of the people I have dealt with in four decades of globetrotting are men and women of integrity and decency, dedicated individuals who look askance at the shady conduct of the minority.

I have known enough business executives, though, who, through greed, arrogance, an unhealthy devotion to Wall Street, or a perverted interpretation of capitalism, have chosen the dark side. Their numbers seem to be growing.

The rationale that everyone fudges, or that you have to cheat to stay competitive is a powerful lure, to be sure. The path to perdition is enticing, slippery, and all downhill. Moral bankruptcy is the inevitable conclusion.

What's needed is a booster shot of commonly held moral principles from the playgrounds of our youth. We all know the drill: Be fair, don't cheat, play nicely, share and share alike, tell the truth. Although these childhood prescriptions may appear to have been forgotten in the fog of competition, I believe it is more a matter of values being expediently ignored. Whatever the case, it is time for us to get into ethical shape with a full-scale behavioral workout.

Financial ends never justify unethical means. Success comes to those who possess skill, courage, integrity, decency, and generosity. Men and women who maintain their universally shared values tend to achieve their goals, know happiness in home and work, and find greater purpose in their lives than simply accumulating wealth.

Nice guys really can and do finish first in life.

![]()

I worked as White House staff secretary and a special assistant to the president during the first term of the Nixon administration. I was the funnel through which passed documents going to and from the president's desk. I also was part of H. R. Haldeman's "super staff." As a member of that team, Haldeman expected me to be unquestioning. It annoyed him that I was not. He proffered blind loyalty to Nixon and demanded the same from his staff. I saw how power was abused, and I didn't buy in. One never has to.

I was asked by Haldeman on one occasion to do something "to help" the president. We were there to serve the president, after all. It seems a certain self-righteous congressman was questioning one of Nixon's nominations for agency head. There was some evidence the nominee had employed undocumented workers in her California business.

Haldeman asked me to check out a factory previously owned by this congressman to see whether the report was true. The facility happened to be located close to my own manufacturing plant in Fullerton, California. Haldeman wanted me to place some of our Latino employees on an undercover operation at the plant in question. The information would be used, of course, to embarrass the political adversary.

An amoral atmosphere had penetrated the White House. Meetings with Haldeman were little more than desperate attempts by underlings to be noticed. We were all under the gun to produce solutions. Too many were willing to do just about anything for Haldeman's nod of approval. That was the pressure that had me picking up the phone to call my plant manager.

There are times when we react too quickly to catch the rightness and wrongness of something immediately. We don't think it through. This was one of those times. It took about 15 minutes for my inner moral compass to make itself noticed, to bring me to the point that I recognized this wasn't the right thing to do. Values that had accompanied me since childhood kicked in.

Halfway through my conversation, I paused. "Wait a minute, Jim," I said deliberately to the general manager of Huntsman Container, "let's not do this. I don't want to play this game. Forget I called."

I instinctively knew it was wrong, but it took a few minutes for the notion to percolate. I informed Haldeman that I would not have my employees spy or do anything like it. To the second most powerful man in America, I was saying no. He didn't appreciate responses like that. He viewed them as signs of disloyalty. I might as well have been saying farewell.

So be it, and I did leave within six months of that incident. My streaks of independence, it turned out, were an exercise in good judgment. I was about the only West Wing staff member not eventually hauled before the congressional Watergate committee or a grand jury.

![]()

Gray is not a substitute for black and white. You don't bump into people without saying you're sorry. When you shake hands, it's supposed to mean something. If someone is in trouble, you reach out. Values aren't to be conveniently molded to fit particular situations. They are indelibly etched in our very beings as natural impulses that never go stale or find themselves out of style.

Some will scoff that this view is an oversimplification in a complex, competitive world. It's simple, all right, but that's the point! It's little more than what we learned as kids, what we accepted as correct behavior before today's pressures tempted some to jettison those values in favor of getting ahead or enhancing bottom lines.

Although the values of our youth, at least to some degree, usually are faith-based, they also are encompassed in natural law. Nearly everyone on the planet, for instance, shares a belief in basic human goodness.

Human beings inherently prize honesty over deceit, even in the remotest corners of the globe. In the extreme northeast of India lies the semi-primitive state of Arunachal Pradesh. Few of us even know it exists. Indeed, this area is nearly forgotten by New Delhi. More than 100 tribes have their own cultures, languages, and animistic religions. Yet, they share several characteristics, including making honesty an absolute value.

How ironic, not to mention shameful, that the most educated and industrialized nations seem to have the most troublesome time with universal values of integrity.

Michael Josephson, who heads the Josephson Institute of Ethics in Marina del Rey, California, says one only has to view popular shows such as The Apprentice and Survivor to get the notion that life's winners are those who deceive others without getting caught. Nobody seems offended by that. It's not so much that temptations are any greater today, Josephson notes, it's that our defenses have weakened.

Be that as it may, I maintain we all know when we bend or break the rules, when we are approaching a boundary, when we do something untoward. Whatever the expedient rationale or the instant gratification that "justified" it, we don't feel quite right about it because we were taught better.

It is this traditional set of behavioral values that will lead us not into temptation but to long-term success. Forget about who finishes first and who finishes last. Decent, honorable people finish races—and their lives—in grand style and with respect.

The twentieth-century explorer Ernest Shackleton, whose legendary, heroic exploits in Antarctica inspired half a dozen books, looked at life as a game to be played fairly and with honor:

Life to me is the greatest of all games. The danger lies in treating it as a trivial game, a game to be taken lightly, and a game in which the rules don't matter much. The rules matter a great deal. The game has to be played fairly or it is no game at all. And even to win the game is not the chief end. The chief end is to win it honorably and splendidly.

![]()

The principles we learned as children were simple and fair. They remain simple and fair. With moral compasses programmed in the sandboxes of long ago, we can navigate career courses with values that guarantee successful lives, a path that is good for one's mental and moral well-being, not to mention long-term material success.

Chapter Two. Check Your Moral Compass

We know darn well what is right and wrong.

WHEN YOUNG MEN OR WOMEN ARE BEGINNING LIFE, THE MOST IMPORTANT PERIOD, IT IS OFTEN SAID, IS THAT IN WHICH THEIR HABITS ARE FORMED. THAT IS A VERY IMPORTANT PERIOD. BUT THE PERIOD IN WHICH THE IDEALS OF THE YOUNG ARE FORMED AND ADOPTED IS MORE IMPORTANT STILL. FOR THE IDEAL WITH WHICH YOU GO FORWARD TO MEASURE THINGS DETERMINES THE NATURE, SO FAR AS YOU ARE CONCERNED, OF EVERYTHING YOU MEET.

—HENRY WARD BEECHER

IT IS NOT OUR AFFLUENCE, OR OUR PLUMBING, OR OUR CLOGGED FREEWAYS THAT GRIP THE IMAGINATION OF OTHERS. RATHER, IT IS THE VALUES UPON WHICH OUR SYSTEM IS BUILT.

—SEN. J. WILLIAM FULBRIGHT

No one is raised in a moral vacuum. Every mentally balanced human being basically recognizes right from wrong. Whether a person is brought up a Christian, Jew, Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu, Unitarian, New Age, a free thinker, or an atheist, he or she is taught from toddler on that you shouldn't lie and there are consequences for doing so.

There is no such thing as a moral agnostic. An amoral person is a moral person who temporarily and creatively disconnects his actions from his values. Each of us possesses a moral GPS, a compass or conscience, if you will, programmed by parents, teachers, coaches, clergy, grandparents, uncles and aunts, scoutmasters, friends, and peers. This compass came with the package and it continues to differentiate between proper and improper courses until the day we expire.

When I was 10 years old, there resided several blocks from our home Edwards Market, one of those old houses with the grocery store in the front and the proprietors' residence in the back. It was only 200 or 300 square feet in size, but at my age the place looked like a supermarket. At the time, I was making about 50 cents a day selling and delivering the local newspaper.

I entered the store while on my route one day and no one seemed to be around. Ice cream sandwiches had just come on the market. It was hot and I wanted to try one. I reached inside the small freezer and grabbed an ice cream bar. I slipped the wrapped sandwich into my pocket. Moments later, Mrs. Edwards appeared, asking if she could help me.

"No, thanks," I answered politely and headed for the door. Just before it slammed shut, I heard her say, "Jon, are you going to pay for that ice cream sandwich?" Embarrassed, I turned around and sheepishly walked back to the freezer where my slightly shaking hand returned the ice cream sandwich to its rightful place. Mrs. Edwards never said another word.

It was a necessary lesson for a young, adventuresome boy, one that I have not forgotten nearly 60 years later. It wasn't at the moment of being exposed that I suddenly realized I had done something wrong. I knew it the second I slipped my hand into the freezer, just as I would know today if I pulled a similar, but more sophisticated, stunt in a business transaction. Each of us is taught it is wrong to take that which doesn't belong to us.

Certain types of behavior encourage a disconnect with our inner compass or conscience: Rationalizing dims caution lights, arrogance blurs boundaries, desperation overrides good sense. Whatever the blinders may be, the right-wrong indicator light continues to flash all the same. We might not ask, but the compass tells.

Some point out that today's society tolerates too much questionable activity, making it difficult for the younger generation to get a consistent fix on right and wrong. Little wonder, goes this line of thought, that when the newest batch of apprentices bolt from their classrooms, their values are open to negotiation.

I am not totally buying in. Society certainly is more permissive than when I was a child, but does anyone today truly condone stealing? Some modern teens may dismiss it, but does any student not consider cheating intrinsically wrong, no matter how many of their friends do it? Does society accept cooking corporate books, embezzlement, fraud, or outlandish perks for corporate executives? The answers, of course, are no.

Basic misbehavior is considered as wrong today as it was 100 years ago, although I grant that today's atmosphere produces more creative and sophisticated rationalizations for such mischief. This is why heeding the advice of George Washington, a man renowned for his integrity, is worthwhile: "Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience."

Humans are the only earthly species that experience guilt. We never see our pet dogs, cats, or canaries acting chagrined for eating too much food or forgetting their manners. (And heaven knows some of them abuse the system.) Humans are unique for their ability to recognize righteous paths from indecent ones. And when we choose the wrong route, we squirm—at least inwardly.

The needle of individual compasses points true. Conceptually, the ethical route is self-evident to reasonable persons.

![]()

We are not always required by law to do what is right and proper. Decency and generosity, for instance, carry no legal mandate. Pure ethics are optional.

Laws define courses to which we must legally adhere or avoid. Ethics are standards of conduct that we ought to follow. There is some overlap of the two, but virtuous behavior usually is left to individual discretion. All the professional training in the world does not guarantee moral leadership. Unlike laws, virtue cannot be politically mandated, let alone enforced by bureaucrats, but that doesn't stop them from trying. Congress considered the corporate world today so challenged when it comes to ethics that it enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in an attempt to regain credibility for the marketplace. Ultimately, though, respect, civility, and integrity will return only upon the individual-by-individual return of values.

Ethical behavior is to business competition what sportsmanship is to athletic contests. We were taught to play by the rules, to be fair, and to show sportsmanship. The rulebook didn't always state specifically that shortcuts were prohibited. It went without saying that every competitor ran around the oval track and didn't cut across the infield.

My grandsons have a special club called The Great, Great Guys Club (The G3 Club). Members have to be at least six years old to attend meetings. It's not permissible to fall asleep, wet your pants, or crawl under the table, among other prohibitions. They set their own rules. Amazingly, the club is quite orderly. Because parents aren't present, it is interesting to observe the standards they establish by themselves. Here are a couple of examples (with Grandpa's literary padding):

• Do what you're supposed to when you are told to do it.

• Kindness and honesty determine heart and character.

• Never tell lies.

• Cover your mouth when you cough or sneeze.

Kids know what's proper behavior even if they don't always show it. Their moral compasses, although still developing, are in working order. They are too young to know they can trade in their conscience for a higher credit rating at Moody's. They instinctively know a conscience at ease is a best friend. They have never heard of Sophocles, but they understand his message: "There is no witness so terrible or no accuser so powerful as the conscience."

Ever notice how little guile youngsters exhibit? How honest they are with observations? How well they play with others? How smoothly they compete when adults aren't present? Sure, there always were—and still are—periodic squabbles, but kids work them out without a 300-page rulebook or a court of law. Sandlot games are played without referees or umpires, clocks, or defined boundary lines. When kids occasionally are thoughtless, it is more a case of spontaneous reaction rather than calculated meanness.

As a rule, playground protocol requires we offer a hand up to flattened opponents, share toys, call out liars and cheaters, play games fairly, and utter expressions of gratitude and praise—please, thanks, nice shot, cool—without prompt. To paraphrase Socrates, clear consciences prompt harmony.

At times, certain students in my tenth-grade biology class would write answers to a forthcoming quiz on the palms of their hands or cuffs of their shirts. Not many tried this because everyone knew cheating was wrong. In addition to the fear of being caught, most students also longed for respect as much as good grades. Once someone saw you cheating, you were never elected to student offices or respected on the sports field. Maybe that was simply part of the innocence of the 1950s, but twenty-first century students still know cheating is wrong, even though they may show more indifference toward this transgression than past generations.

People often offer as an excuse for lying, cheating, and fraud that they were pressured into it by high expectations or that "everyone does it." Some will claim that it is the only way they can keep up. Those excuses sound better than the real reasons they choose the improper course: arrogance, power trips, greed, and lack of backbone, all of which are equal-opportunity afflictions. One's economic status, sphere of influence, religious upbringing, or political persuasions never seem to be factors in determining whom these viruses will next ensnare.

There is contained in every rationale and every excuse, bogus as each ultimately ends up being, an awareness of impropriety. Succeeding or getting to the top at all costs by definition is an immoral goal. The ingredients for long-term success—courage, vision, follow-through, risk, opportunity, sweat, sacrifice, skill, discipline, honesty—never vary. And we all know this.

However, in the winner-take-all atmosphere of today's marketplace, shortcuts to success, at least initially, are alluring, and lying often can be lucrative. That said, scammers, cheaters, spitball pitchers, shell-and-pea artists, and the like historically have never prevailed for long. And when their fall does come, it is fast, painful, and lasting.

Whether exaggerating resumés or revenues, people attempt, when discovered, to quickly justify their unethical conduct. Enron officials rationalized from the beginning, same with Tyco brass, but the improper path is never required in the legitimate marketplace.

Values provide us with ethical water wings whose deployment is as critical in today's wave-tossed corporate boardrooms as they were in yesterday's classrooms.

Chapter Three. Play by the Rules

Compete fiercely and fairly—but no cutting in line.

BECAUSE JUST AS GOOD MORALS, IF THEY ARE TO BE MAINTAINED, HAVE NEED OF THE LAWS, SO THE LAWS, IF THEY ARE TO BE OBSERVED, HAVE NEED OF GOOD MORALS.

—MACHIAVELLI

THE SECRET OF LIFE IS HONESTY AND FAIR DEALING. IF YOU CAN FAKE THAT, YOU'VE GOT IT MADE.

—GROUCHO MARX

AMERICANISM MEANS THE VIRTUES OF COURAGE, HONOR, JUSTICE, TRUTH, SINCERITY, AND HARDIHOOD—THE VIRTUES THAT MADE AMERICA. THE THINGS THAT WILL DESTROY AMERICA ARE PROSPERITY-AT-ANY-PRICE... THE LOVE OF SOFT LIVING AND THE GET-RICH-QUICK THEORY OF LIFE.

—THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Which rules we honor and which we ignore determine personal character, and it is character that determines how closely we will allow our value system to affect our lives.

Early on, infused with moral purpose by those who influenced us, we learned what counted and what didn't. The Golden Rule, proper table manners, respecting others, good sportsmanship, the unwritten codes such as no cutting in line and sharing—all these allowed us to develop character.

Character is most determined by integrity and courage. Your reputation is how others perceive you. Character is how you act when no one is watching.

These traits, or lack thereof, are the foundation of life's moral decisions. Once dishonesty is introduced, distrust becomes the hallmark of future dealings or associations. The eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson had this in mind: "Without staunch adherence to truth-telling, all confidence in communication would be lost."

Businessmen and -women do not place their integrity in jeopardy by driving hard bargains, negotiating intensely, or fiercely seeking every legitimate advantage. Tough negotiations, however, must be fair and honest. That way, you never have to remember what you said the previous day.

I bargain simply as a matter of principle, whether it is a $1 purchase or a $1 billion acquisition. Negotiating excites me, but gaining an edge must never come at the expense of misrepresentation or bribery. In addition to being morally wrong, they take the fun out of cutting a deal.

Bribes and scams may produce temporary advantages, but the practice carries an enormous price tag. It cheapens the way business is done, enriches only a few corrupt individuals, and makes a mockery of the rules of play.

In the 1980s, Huntsman Chemical opened a plant in Thailand. Mitsubishi was a partner in this joint venture, which we called HMT. With about $30 million invested, HMT announced the construction of a second site. I had a working relationship with the country's minister of finance, who never missed an opportunity to suggest it could be closer.

I went to his home for dinner one evening where he showed me 19 new Cadillacs parked in his garage, which he described as "gifts" from foreign companies. I explained the Huntsman company didn't engage in that sort of thing, a fact he smilingly acknowledged.

Several months later, I received a call from the Mitsubishi executive in Tokyo responsible for Thailand operations. He stated HMT had to pay various government officials kickbacks annually to do business and that our share of this joint obligation was $250,000 for that year.

I said we had no intention of paying even five cents toward what was nothing more than extortion. He told me every company in Thailand paid these "fees" in order to be guaranteed access to the industrial sites. As it turned out and without our knowledge, Mitsubishi had been paying our share up to this point as the cost of doing business, but had decided it was time Huntsman Chemical carried its own baggage.

The next day, I informed Mitsubishi we were selling our interest. After failing to talk me out of it, Mitsubishi paid us a discounted price for our interest in HMT. We lost about $3 million short term. Long haul, it was a blessing in disguise. When the Asian economic crisis came several years down the road, the entire industry went down the drain.

In America and Western Europe, we proclaim high standards when it comes to things such as paying bribes, but we don't always practice what we preach. Ethical decisions can be cumbersome and unprofitable in the near term, but after our refusal to pay "fees" in Thailand became known, we never had a problem over bribes again in that part of the world. The word got out: Huntsman just says no. And so do many other companies.

Once you compromise your values by agreeing to bribes or payoffs, it is difficult ever to reestablish your reputation or credibility. Therefore, carefully choose your partners, be they individuals, companies, or nations.

I have a reputation as a tough but straightforward negotiator. I deal hard and intensely—and always from the top of the deck. Because it is perceived I usually end up on the better side of the bargain, I actually had one CEO refuse to negotiate a merger with me. He was afraid he would be perceived in the industry as having "lost his pants" or that he sold at the wrong time for the wrong price, but I have never had anyone refuse to deal with me for lack of trust.

Competition is an integral part of the entrepreneurial spirit and the free market. Cheating and lying are not. If the immoral nature of cheating and lying doesn't particularly bother you, think about this: They eventually lead to failure.

Remember the old chant: "Winners never cheat; cheaters never win"? And, as kids, we would chide those whom we perceived to be not telling the truth with: Liar, liar, pants on fire. Those childish taunts actually hold true today. Moral shortcuts always have a way of catching up.

In the Shinto religion, there is this teaching: "If you plot and connive to deceive people, you may fool them for a while and profit thereby, but you will without fail be visited by divine punishment." I hasten to add that temporal judgment also awaits. There is always a payback for indecent behavior.

Consider this parable: On a late-night flight over the ocean, the pilot announces good news and bad news. "The bad news is we have lost radio contact, our radar doesn't work, and clouds are blocking our view of the stars. The good news is there is a strong tailwind and we are making excellent time."

![]()

There are many professions in which one can find examples of hollow values, but nowhere is it more evident than on Wall Street, where the ruling ethos seems to be the more you deceive the other guy, the more money you make. It was none other than Abraham Lincoln who reminded us: "There is no more difficult place to find an honest man than on Wall Street in New York City."

I have spent nearly 40 years negotiating deals on Wall Street and have found few completely honest individuals. Those who are trustworthy and honorable are rare—but wonderful professionals. Some of my closest friends are found in this small cadre, be they in New York City or Salt Lake City. Those who choose to mislead others discover that this is not the type of corruption that sends people to prison. It is more a matter of intellectual dishonesty and lack of personal ethics. Compensation has replaced ethics as a governing principle. Wall Street has but one objective and one value: How much money can be made?

Wall Street thinks there is nothing wrong with this sort of behavior because everyone does it, but the lack of a sense of integrity also produces a lack of respect. WorldCom, Tyco, Enron, and other giant companies had leaders who failed to play fair.

Because they cheated, they lost. Accumulation of wealth became a driving force to these executives. They forgot the golden rule of integrity: Trust is a greater compliment than affection. With integrity comes respect.

Real winners never sneak to finish lines by clandestine or compromised routes. They do it the old-fashioned way—with talent, hard work, and honesty. It's okay to negotiate tough business deals, but do it with both hands on the table and sleeves rolled up.

Make it a point to never misrepresent or to take unfair advantage of someone. That way, you can count on second and third deals with companies after successfully completing the first one. Have as a goal both sides feeling they achieved their respective objectives.

In 1999, I was in fierce negotiations with Charles Miller Smith, then president and CEO of Imperial Chemical Industries of Great Britain, one of that nation's largest companies. We wanted to acquire some of ICI's chemical divisions. It would be the largest deal of my life, a merger that would double the size of Huntsman Corp. It was a complicated transaction with intense pressure on each side. Charles needed to get a good price to reduce some ICI debt; I had a limited amount of capital for the acquisition.

During the extended negotiations, Charles' wife was suffering from terminal cancer. Toward the end of our negotiations, he became emotionally distracted. When his wife passed away, he was distraught, as one can imagine. We still had not completed our negotiations.

I decided the fine points of the last 20 percent of the deal would stand as they were proposed. I probably could have clawed another $200 million out of the deal, but it would have come at the expense of Charles' emotional state. The agreement as it stood was good enough. Each side came out a winner, and I made a lifelong friend.

![]()

Every family, home, and school classroom has its standards. There is little confusion over boundary lines. Even professing not to understand the rules when caught breaking one acknowledges a transgression has occurred. But what happens when some of these children turn into adults? Why are these home and classroom rules so ignored? Why is improper behavior rationalized, even justified, when inside we know better? Some sinister force must take over in the late teens in which finding ways to circumvent traditional standards becomes acceptable.

As a teenager, my father would order me to be home by 8 o'clock. He didn't say "a.m." or "p.m." I knew he meant 8 that night. There was no fine print to detail what was meant when he said he did not want "me" driving the family Ford. Although technically, he only said I shouldn't drive that 1936 Ford coupe, he was including my friends. (A lawyer might have counseled that, technically, only I was prohibited. Unless my dad specifically stipulated my buddy or class of people in that prohibition, anyone but me was legally allowed to drive, but I knew better.)

As we grow older, our rationale for not abiding by the rules would make a master storyteller green with envy. We blame situations or others. The dog ate the homework that we ignored. We rationalize that immoral behavior is accepted practice. Shifting responsibility away from ourselves has become an art form.

In fact, we employ the same feeble excuses we did as children when we were caught doing something improper, something we knew we shouldn't be doing. Adults believe they are more convincing. We aren't. The "everyone does it" line didn't work as a teenager, and it won't work now. It's a total copout and easily trumped. Everybody is not doing it. Even if they were, it still is wrong—and we know it's wrong.

Then there's that old, sheepish excuse: "The devil made me do it." The devil never makes you do anything. Be honest. Improper actions often appear easier routes, or require no courage, or are temporarily advantageous.

If only Richard Nixon had admitted mistakes up front and taken responsibility for the improper conduct of his subordinates, something deep down he knew to be wrong, the American public would have forgiven him. With a sense of contrition, he could have created a presidential benchmark.

![]()

Children observe their elders so they know how to act. Employees watch supervisors. Citizens eye civic and political leaders. If these leaders and role models set bad examples, those following frequently follow suit. It's that simple.

There are no moral shortcuts in the game of business—or life. There are, basically, three kinds of people: the unsuccessful, the temporarily successful, and those who become and remain successful. The difference is character.

Chapter Four. Setting the Example

Risk, responsibility, reliability— the three Rs of leadership.

PEOPLE SEE SUCCESSES THAT MEN HAVE MADE AND SOMEHOW THEY APPEAR TO BE EASY. BUT THAT IS A WORLD AWAY FROM THE FACTS. IT IS FAILURE THAT IS EASY. SUCCESS IS ALWAYS HARD. A MAN CAN FAIL EASILY; HE CAN SUCCEED ONLY BY PAYING OUT ALL THAT HE HAS AND IS.

—HENRY FORD

A SHIP IN HARBOR IS SAFE, BUT THAT IS NOT WHAT SHIPS ARE BUILT FOR.

—WILLIAM SHEDD

I have always loved the biblical passage, "Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap." It describes leadership responsibility clearly and concisely, the precise spot where the buck stops. The lesson is clear: Careful cultivation pays off. Parents and employers who nurture, praise, and when necessary, discipline fairly, experience happier and more successful lives for themselves and those in their charge.

Nothing new, you say? I agree, but we need reminders of this point to help overcome unforeseen or uncontrollable obstacles that cloud end results.

In the marketplace, we may do everything in our power to reap plentiful profits, but because of good-faith miscalculations, malevolence, negative markets, or acts of nature, a successful yield escapes us. My youthful years spent working on a potato farm taught me how an early frost or heavy rains can adversely affect the harvest no matter how carefully we tended the crop.

Fumbling by our own hand or someone else's also can ruin things. In spite of inspired vision, the purest of intentions, exemplary dedication, and great skills, success is never guaranteed. What's important is that the person in charge takes responsibility for the outcome, be it good, bad, or ugly. Surround yourself with the best people available and then accept responsibility.

As a naval officer aboard the U.S.S. Calvert in the South China Sea in 1960, I learned this lesson firsthand. My commanding officer, Captain Richard Collum, was a World War II veteran whom I greatly admired. On one occasion, we were to rendezvous the ships of our squadron with naval ships from seven other nations. The Calvert was carrying the admiral or, in naval parlance, the Flag. Every ship followed the lead of the flagship.

It was 4 a.m. and I was the officer of the deck. As a 23-year-old lieutenant (j.g.), I had much to learn in life, yet I alone had been given the great responsibility of directing the formation of the ships during those early morning hours.

At 4:35 a.m., I ordered the helmsman: "Come right to course 335." The helmsman shouted back confirmation, as is traditional in the navy: "Coming right to course 355."

I thought all was well, but I had not clearly heard his erroneous response. He thought I had ordered "355" degrees, rather than "335." As we made the incorrect turn, the remaining ships followed. We were off course by 20 degrees.

Some of the ships realized the error and returned to the proper course. Others did not. The formation was in dangerous disarray. Avoiding collisions caused a massive entanglement—and it was my fault. Fortunately, no damage was done, except to my self-confidence. I felt a sense of ruination and failure. How could one issue an order to the helmsman, have it reported back in error, and not catch the discrepancy? After all, repeating the order is the fail-safe mechanism for alerting one to such misunderstandings.

Learning of the debacle, Captain Collum came running to the bridge in his bathrobe and immediately took over, relieving an embarrassed young lieutenant. I was devastated. The 42 ships in our squadron took several hours to realign. Later, when the seas were calm and order had been restored, the captain called me to his cabin.

"Lt. Huntsman," he said, "you learned a valuable lesson today."

"No, sir," I responded, "I felt a great sense of embarrassment and I let down you and my shipmates."

"To the contrary, lieutenant, now you never again will permit such an act to occur. You will stay on top of every order you ever give. This will be a life-long learning experience for you. I am the captain of the ship. Everything that happens is my responsibility. You may not have caught the helmsman's mistake, but I am responsible for it. The navy would hold a court martial for me if any of the ships had collided during that exercise."

I learned then and there what it means to be a leader. Even though the commanding officer was asleep, my actions were his actions. I also learned another lesson: By reassuring a young lieutenant that he still had the captain's confidence, he extended hope for the future.

I would repeat that scenario (the captain's, not the lieutenant's) many times as head of Huntsman Corp. Reprove faults in a way that keeps intact self-confidence and commitment to do better. As a CEO, I accepted responsibility for our plants, even though some of them were a half a world away. CEOs are charged by their directors to guarantee the good conduct and safety of employees and the company.

![]()

The marketplace has many leaders—certainly in title. Leadership in the true sense of the word, I'm afraid, is not so abundant. The top executives of some leading businesses haven't the slightest idea of the breadth of stakeholder expectations. That's the result of "leaders" simply being appointed to the position or who found themselves at the top of a corporate chart, next in line for the top job. Real leadership demands character.

Leadership is found in all walks of society: business, political, parental, athletic, military, religious, media, intellectual, entertainment, academic, and so forth. In every instance, leadership cannot exist in a vacuum. By definition, it requires others, those who would be led—and seldom are they a docile group.

Effective, respected leadership is maintained through mutual agreement. Leadership demanded is leadership denied. Leadership is not meant to be dominion over others. Rather, it is the composite of characteristics that earns respect, results, and a continued following.

![]()

Leadership demands decisiveness and that is why it is absolutely critical that leaders know the facts. To ensure that critical information and solid advice reaches them, leaders must surround themselves with capable, strong, competent advisors—and then listen.

Unfortunately, many companies and organizations are led by executives who fear bold, candid, and talented subordinates. They seek only solicitous yes-types. They embrace adulation, not leadership. The great industrialist Henry J. Kaiser had no time for spineless messengers. "Bring me bad news," he demanded of subordinates. "Good news weakens me."

It also matters that top leaders have experience. In times of crisis, experience counts. Soldiers in combat situations prefer to follow battle-tested veterans rather than fuzzy-faced lieutenants fresh out of ROTC. It's no different in other walks of life.

Leaders must show affection and concern for those under their responsibility. Those who would render loyalty to a leader want to know they are appreciated. Whether or not they realize it, executives in leadership roles solely for the four Ps—pay, perks, power, and prestige—essentially are on their way out.

![]()

Leadership is about taking risks. If your life is free of failure, you aren't much of a leader. Take no risks and you risk more than ever. Leaders are called on to enter arenas where success isn't covered by the warranty, where public failure is a real possibility. It's a scary scenario.

A 2004 survey found that 3 in 5 senior executives at Fortune 1,000 companies have no desire to become a CEO. That's twice the number compared to the first such survey conducted in 2001. Why? The risks.

The chance of making mistakes increases dramatically with leadership, no matter its nature or level, but never having failed is never having led.

To succeed, we must attempt new things. Success rates were never a consideration as youngsters when we tried our first hesitant steps, when we learned to use a toilet, when it came to correctly aiming the spoon at an open mouth, or when we decided it was time to tie our own shoelaces. As children, we understood fumbling comes with beginnings. Temporary failures never got in the way of those grand, early-life ventures.

Mistakes are not the problem. How one identifies and corrects errors, how one turns failure into a new opportunity, determines the quality and durability of leadership. Watergate wasn't so much a burglary as it was the failure to recognize mistakes, to take responsibility for them, and to apologize accordingly.

Those who prefer jeering and ridiculing on the sidelines when the players err or stumble just don't get it: Mistakes and miscues often are transformed into meaningful, successful experiences. Keep in mind the old saying: "Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from poor judgment."

I am reminded of a great observation from President Teddy Roosevelt in which he places the participant and the belittler in perspective:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, and comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause, who at best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

True leaders ought not worry greatly about occasional mistakes, but they must vigilantly guard against those things that will make them feel ashamed.

That said, though, repeating the same mistake too many times makes one a partner to the error. Strong leaders accept responsibility for problems and deal with them swiftly and fairly. If the problem is your responsibility, so is the solution.

Risk was a favorite topic around the dinner table as my children were advancing through their elementary and high school years. It prompted a couple of my sons a few years later to immediately jump into the commodities market and lose their shirts. They misinterpreted my advice (although I admit to doing the same thing in my younger years). Leaders clearly have to take measured risks.

![]()

Leaders can come in different forms and flavors, but core elements rarely vary: integrity, courage, vision, commitment, empathy, humility, and confidence. The greater these attributes, the stronger the leadership.

Many business executives seek only breathtaking compensation and perks. Legions of politicians desire only to remain in office and lead with their own self-interests in mind. There are religious leaders who bathe in reverential treatment. And we all are familiar with celebrities who are addicted to adoring fans. None of that is leadership. Successful leaders maintain their positions through respect earned the old-fashioned way.

On the wall of my office, there hangs a plaque on which are inscribed the words of legendary CBS newscaster Edward R. Murrow: "Difficulty is the one excuse that history never accepts."

I made sure my children understood what that meant. Life is difficult and success even more so, but anything worth doing must be challenging. Engaging in activities devoid of difficulty, lounging in risk-free zones, is life without great meaning. Children are perceptive. They learn as much from observation as from participation, so parental leaders especially need to practice what they preach.

![]()

In 2001, our company was on the verge of bankruptcy. Our high-yield bonds were trading at 25 cents on the dollar. Our financial and legal teams had brought in bankruptcy specialists from Los Angeles and New York. In their united opinion, bankruptcy was inevitable. Although I had passed the CEO reins to my son Peter, I was still chairman of the board. I was also the company's largest shareholder.

For me, bankruptcy was not an option. It was our name on the front door. Family character was at stake. Virtually all of the 87 lenders we dealt with at the time believed we would crash. Cash was tight. We were in a recession. Our industry was overproducing; profit margins were dropping. Exports had shrunk. Energy costs were spiraling out of control.

In the middle of that perfect storm, we were hit by a rogue wave, the 9/11 catastrophe.

I reminded myself in the midst of this turmoil how grateful I was that I had been chosen to lead the company at this time because I was convinced I could guide our company through this unprecedented siege. This company would not be seized by corporate lawyers, bankers, and highly paid consultants with all the answers on my watch. Not one of them could truly comprehend my notions of character and integrity.

We initiated cost-cutting programs on all levels and at all geographic locations, negotiated an equity position for bondholders, and refinanced our debt with those 87 lenders. We raised additional capital to help pay down that debt. Piece by piece, we put the complex financial mosaic back together. It would have been much easier to have chosen bankruptcy, but two and a half years later, Huntsman Corp. emerged stronger than ever. Wall Street was amazed.

A crisis allows us the opportunity to dip deep into the reservoirs of our very being, to rise to levels of confidence, strength, and resolve that otherwise we didn't think we possessed. Through adversity, we come face to face with who we really are and what really counts.

![]()

Leadership calls for a high degree of confidence, a requirement that keeps many people from wanting to be in charge of problematic situations. To believe in one's self, to not be swayed by the emotions of the moment, to tap the reserves of unused power and inner forces, provide the energy to lead. One must have the confidence that he or she will survive when others expire.

There is a great "can do" spirit in each of us, ready to be set free. We all have reserves to tap in times of danger. In a crisis, a person's mind can be brilliant and highly creative; true character is revealed.

Leaders are selected to take the extra steps, to display moral courage, to reach above and beyond, and to make it to the end zone. For, at the end of the day, leaders have to score or it doesn't count.

![]()

In today's what's-in-it-for-me environment, humility is vital for good leadership. One must be teachable and recognize the value of others in bringing about positive solutions.

I recently met with my old friend Jeroen van der Veer, chief executive of Royal Dutch/Shell Group, at his office at The Hague. Jeroen was president of Shell Chemical Company in Houston during the early 1990s. It was clear to me then that he was on his way upward to the most senior position in the world's largest company. We became trusted friends.

I asked him his thoughts on leadership. "The one common value that most leaders lack today, whether in business, politics, or religion," he replied, "is humility." He cited several cases where high-profile individuals fell from exalted positions because they refused to be teachable and humble.

"They knew all the answers and refused to listen to wise and prudent counsel of others. Their prime focus should be to create other leaders, the long term and a certain modesty about their own capabilities."

Additionally, leaders need to be candid with those they purport to lead. Sharing good news is easy. When it comes to the more troublesome negative news, be candid and take responsibility. Don't withhold unpleasant possibilities and don't pass off bad news to subordinates to deliver. Level with employees about problems in a timely fashion.

When I was in the ninth grade, I secured a job assembling wagons and tricycles at a Payless Drug-store. On Christmas Eve, the store manager presented me with a box of cherry chocolates—and laid me off. I was stunned. The manager never indicated the position was temporary. It left such an awful impression on me that I vowed I would always be up front with employees when it came to the possibility of layoffs.

![]()

Leadership must be genuine, energetic, and engaged. I have served as a director on five major New York Stock Exchange boards in the past 25 years. During that time, I have met few men and women who I felt were really providing help to the companies involved. Directors regularly make foolish, Wall Street–driven decisions, harmful to the long-term health of the company, because of today's addiction to short-term gains.

You would think that most corporate directors know better. They are, after all, supposed to be bright, successful individuals. Unfortunately, many of today's boards are little more than social clubs that do a poor job of protecting the long-term interests of stockholders.

Most corporate directors lack expertise in the industry of the company they are directing. Management easily manipulates such directors because the latter's chief concerns are fees, retirement benefits, and the prestige of being on a corporate board. Typically, they have only a small portion of their net worth invested in the company. They loathe being at odds with the CEO, chairman, or other directors.

Stockholders would be outraged if they were aware of the lack of focus, expertise, connectivity, and good judgment exhibited by a sizable number of corporate directors. Although these directors occasionally fire the CEO in a huff when a deal doesn't work out or an ethical gaffe is exposed, they would better meet their obligations if they stopped CEOs from making bad deals or unethical decisions in the first place.

Always cheer for the individual director who breaks ranks to propose a novel route, who offers a different perspective, who raises ethical concerns, or who focuses on the long-term well being of stockholders.

I have great respect for many CEOs in today's business world. They are dedicated, gifted, and honest men and women. They appreciate why they were chosen to lead their respective companies. They accept their duties: keep business healthy; deliver a fair profit in the most professional, socially responsible way possible; display moral backbone; and be forthcoming.

![]()

When the ship finds itself in trouble, as my earlier story related, all eyes turn to the captain. Subordinates may have been the ones who erred, but it is the captain who must take responsibility for the mistake and for steering the ship out of trouble. And, be assured, it takes more effort correcting a mistake than it takes to make it.

Leadership is a privilege. Those who receive the mantle must also know that they can expect an accounting of their stewardships.

It is not uncommon for people to forego higher salaries to join an organization with strong, ethical leadership. Most individuals desire leadership they can both admire and respect. They want to be in sync with that brand of leader, and will often parallel their own lives after that person, whether in a corporate, religious, political, parental, teaching, or other setting.

A good example of this is Mitt Romney, currently governor of Massachusetts, who returned integrity to the scandal-ridden 2002 Winter Olympics. That classic show of leadership was infectious all the way through the Olympic organization to the thousands of volunteers. As a result, those Games came off the most successful and problem-free in recent Olympics history.

Conversely, because leaders are watched and emulated, their engagement in unethical or illegal conduct can have a devastating effect on others.

![]()

Courage may be the single most important factor in identifying leadership. Individuals may know well what is right and what is wrong but fail to act decisively because they lack the courage their values require.

Leaders—whether inside families, corporations, groups, or politics—must be prepared to stand against the crowd when their moral values are challenged. They must ignore criticism and taunts if pursuing a right and just route. Leadership is supposed to be daunting. Courage is an absolute requisite. Without it, noted Winston Churchill, other virtues lose their meaning. "Courage is the first of the human qualities because it is a quality which guarantees all the others."

Some economists argue that business leaders have but a single responsibility: to employ every legal means to increase corporate profits. Commercial enterprise, such economists reason, is amoral by nature. Compete openly and freely in any way you wish so long as you do not engage in deception and fraud (rule-book violations).

Embracing that sort of credo, it is not hard to see why executives rationalize ethical corner cutting or how impressionable business-school students are turned loose on the marketplace without the proper emphasis on morality. Humility, decency, and social leadership appear to be irrelevant.

The gospel according to these economists implies that if somehow one finds a loophole in a law prohibiting shortcuts across the infield, one does not have to remain on the same oval track with the other racers. One is allowed—no, obligated—to maximize results under the broadest interpretation of the official rules of conduct, however bent, loopholed, or indecent it may be.