Discover Your Inner Negotiators

Every game is composed of two parts, an outer game and an inner game. The outer game is played against an external opponent to overcome external obstacles, and to reach an external goal. . . . The inner game . . . is the game that takes place in the mind of the player . . . and it is played to overcome all habits of mind which inhibit excellence in performance.

—W. TIMOTHY GALLWEY

Giovanna was a sales manager at a national insurance carrier. She was in charge of driving new business and increasing premium income in her territory. She also oversaw several teams of sales representatives.

Giovanna was frustrated at getting passed over for promotion twice in a row. She couldn’t understand the problem, since her performance was stellar. Her sales reps met their premium targets; her agents offered competitive prices to consumers; she paid out losses when it was fair, and she refused to pay when her investigators found fraud. Her territory improved its profitability every year she was in charge. She’d even extended the company’s service lines—it now offered life insurance in packages that covered only auto and home in the past.

The first time she came up for promotion and didn’t get it, Giovanna didn’t say anything. The second time, she confronted her director of sales and demanded an explanation.

“To be perfectly blunt,” he told her, “your sales teams don’t want to work for you.”

He continued.

“Several team members have complained about your forcefulness when negotiating over sales targets, or commented on your hostility when you’re under stress.” He claimed that someone had mentioned her “aggressive” behavior as their reason for leaving the firm. “Frankly, until you get your management style under control, you’re not going to see any promotions.”

Giovanna was shocked.

I met with her a few weeks after that conversation, because she’d asked for a coach. When I asked her about how she worked with teams, she described herself as friendly, motivated, and applying high standards of excellence. I asked if she worked people very hard, and she said no, not really. “I don’t ask them to do anything I don’t do myself.”

We agreed that I’d speak with a range of her co-workers, and bring back my observations for further discussion.

To Close Your Performance Gap, You Need to See It

After talking with a bunch of people, I learned that the feedback Giovanna’s boss had shared wasn’t far off base. Her teams were alarmed by her temper and felt too intimidated to state their opinions. One person acknowledged her ability to get results. He quickly added that she was “a bully,” so he didn’t want to work with her.

I collected more information to test what I was hearing. A former team member who’d switched territories commented on Giovanna’s intelligence and integrity. She’d made the change because she wanted a better quality of life. “Giovanna is one of the best in the business. I know I could learn a lot from her. She’s just so driven—I could never keep up. She only saw how I could do better—she never noticed what I did well. And sometimes I just needed a break. But I was afraid to ask.”

When I brought these impressions back to her, Giovanna was taken aback. She said she had “no idea” why anyone would say those harsh things. In fact, she came up with several theories to explain it, none of them relating to her management style. Maybe people were jealous of her all-star results? Or maybe they didn’t want another woman rising into the ranks of leadership? I had my work cut out for me to help her connect herself in any way to the delay in her career progress.

Seeing Your Gap Means Expanding Your Profile

The first step in closing your Performance Gap is seeing your own role in the results you’re getting. Giovanna can muse about jealous colleagues all she likes. It isn’t going to get her promoted any faster.

Here’s the tricky part. In order for her to see how she’s getting in her own way, Giovanna needs to admit and accept something about herself that she doesn’t recognize yet. It’s not that she hasn’t heard the feedback. It’s that she can’t believe it without changing something about her profile, the way she defines herself to herself.

In the story she tells about herself, Giovanna is a principled, hardworking, and very successful businesswoman. She sees herself as a mentor who’s committed to developing her teams. In fact, she goes out of her way to show them opportunities for improvement. She connects people on LinkedIn. She gives that little extra push so they’ll stretch and grow. Her teams do work hard. But she always gives time off when people ask for it, no questions asked. Nowhere in her current autobiography is there room for Giovanna the Bully.

Seeing Your Performance Gap Enables Accountability

Normally we’d think someone needs to be honest with her, to tell her the hard truth. But she has the facts. People say she’s a bully. They feel intimidated by her. They change territories or leave the company to avoid working with her. Until she registers that she has an aggressive side, and integrates the information that she becomes hostile under stress, she has no way to take accountability for the reactions she’s getting.

Here’s the rub: Giovanna will only close her Performance Gap for real when she meets those sides of herself, and lets them into her profile. Until then, she’ll keep doing what she’s doing now: make things up about the motivations of other people to explain why they say these mean—and untrue—things about her. In other words, she’ll point fingers rather than take accountability. What else can she do? No one wants to take responsibility for something they believe they didn’t do.

Once she knows about Giovanna the Bully, she can make a deal, negotiate an arrangement where Bully Giovanna can use her strength for good, and temper her hostility by partnering with Giovanna the Mentor. She can’t broker any internal agreements, though, until she knows which negotiators to bring to the table.

Now, you might ask, why should she “negotiate” with her inner bully? Shouldn’t she just get rid of the bully?

Fair question. Certainly the world doesn’t need more bullies. The short answer is no, she shouldn’t. For one, because she can’t eliminate the drive that comes out in the bully. And for two, that drive has constructive potential, if she directs it differently. She’s pushing now in unconstructive ways, partially because that drive isn’t balanced by something else. But that doesn’t mean she can’t change her ways.

When the forceful part of her works in tandem with the supportive mentor in her profile, she can combine her inner achiever’s drive with care for her team. Giovanna can still crusade for great results while leaving the hammer at home.

Now, let’s say Giovanna gets the right parties to the inner table. She wants an arrangement that works better. But she doesn’t know how. She can’t work this out until she knows how to negotiate with herself.

Close the Performance Gap by Negotiating with Yourself

The next step in closing your Performance Gap and developing lasting change is learning to negotiate with yourself.

Negotiate with yourself?

At first this idea sounds strange. Can you talk to yourself without being crazy? Can you disagree with yourself? If you have an argument with yourself, who wins?

As we just saw, our sales manager needs to negotiate a new deal with herself. Mentor Giovanna needs to bargain with Bully Giovanna, so she can get promoted. The two sides need to forge a new way to make friends and influence people. Mentor Giovanna can try to sidestep her inner bully. But she’ll start to see lasting change only when she brokers a truce that both sides accept.

At the start of my workshops, I ask people for examples of “negotiating with yourself.” It’s actually not hard to brainstorm a list once you think about it.

People usually come up with personal examples first: Should I eat the ice cream or stick to my diet? Make a scene with the garage for charging more than the estimate, or just pay the bill and move on? Accept the “friend” request from my high school nemesis, or have twenty years not removed the sting?

Soon, the list of topics grows more serious, and often turns to work:

■ Should I raise that difficult topic today?

■ Say yes to please my boss, or admit my plate is full?

■ I want to approach my colleague who’s back from bereavement leave, but then I tell myself it’s none of my business.

■ My client is pushing me hard to do something questionable. Technically speaking, it’s not against the written rules. On the other hand, it feels a bit unethical. Should I say no?

■ We’re nearing our fund-raising target, but we’re not quite there. Our biggest donor said I could ask him for more money if we fell short, but I feel awkward going back to him again.

As we go about the ordinary business of every day, there are inner commentators competing for our attention. At times they speak nicely. But often their voices debate each other like hostile adversaries on talk radio.

As you know by now, I think of them as negotiating parties—your inner negotiators. Like actual individuals, these internal negotiators have a range of styles, motivations, and rules of engagement. They have their own interests and preferred outcomes.

I suspect you’re no stranger to this inner tug-of-war. A sarcastic part of you wants to make a cutting remark when a colleague “forgets” again to do his part. Your kinder side tells you to talk to him about what’s distracting him. The fed-up parent in you wants to scream your head off at your teenager for leaving another mess. Your more grounded side knows you should set up a family meeting about chores and responsibilities. Your generous side leans toward loaning more money to your friend who can’t seem to manage her debts. But a self-protective voice in you hesitates, whispering in your ear, “She’s never paid you back before, and she won’t pay you back this time. You need money, too, you know.”

These voices can become like bullhorns on a football field, roaring for your attention, when you turn to the most important questions and choices in your life. The risk-taker in you demands that you walk out on a lousy job; the side that worries about the mortgage begs you to keep trying. The dream of your own baby pulls you to do one more round of IVF. Meanwhile the voice of reason looks at the statistics and counsels you, “Just face it. You’re not going to conceive, and you should let this go.”

Whether these debates continue all day—or for weeks or months—these conflicting voices and the inner turmoil they create leave you ill equipped to make good choices, take effective action, or sleep well at night. They make it difficult to lead your life, and sometimes nearly impossible to lead your organization. Unresolved inner conflicts also prevent you from jumping on opportunities that could take you to a whole new level.

Like Giovanna, your journey toward self-mastery involves:

1. Learning to recognize your inner negotiators

2. Learning to accept and appreciate them

3. Learning to negotiate with them to broker a new deal

4. Learning to anchor in your center of well-being

5. Learning to maintain centering practices over time.

Discover Your Team of Inner Negotiators

Since you first learned about Freud and what he called the ego, id, and superego, you’ve heard the idea that there’s more to you than meets the eye. You might have come across newer ways to name different parts of you: the inner critic; the people-pleaser; the perfectionist; the inner child. Or this concept might seem completely new to you. You might be asking, how can you negotiate with yourself? You might wonder whether distinct “parts” of you even exist.

They really do.

Today, science can prove what theorists have long believed: you are a complex ecosystem, delicately balancing interdependent parts in the shared habitat called “you.” Neuroscientists who’ve mapped the brain confirm that what appears to you and me like a singular mind is, in fact, a combination of many interconnecting parts.

Science writer Steven Johnson describes this in Mind Wide Open:

[T]he more you learn about the brain’s architecture, the more you recognize that what happens in your head is more like an orchestra than a soloist, with dozens of players contributing to the overall mix. You can hear the symphony as a unified wash of sound, but you can also distinguish the trombones from the timpani, the violins from the cellos.

Sophisticated technology now shows what social science had already claimed: that we’re multi-faceted, made of distinct parts with various functions.

Psychologist Jay Earley described this well when he wrote, “the human mind isn’t a unitary thing that sometimes has irrational feelings. It is a complex system of interacting parts, each with a mind of its own.” Daniel Goleman expressed a similar idea in Emotional Intelligence, writing that “in a very real sense we have two minds, one that thinks and one that feels.”

Long before this era of modern psychology, this same idea was famously expressed by Walt Whitman in Song of Myself: “I am large. I contain multitudes.”

Who Was That Masked Man?

If you’re still not sure about these “inner negotiators,” that’s fine. See if this helps.

Have you ever found yourself thinking or saying anything like this?

I don’t know why I said that—I didn’t mean it.

That was strange—something just came over me.

Where did that come from? I didn’t know I felt so strongly.

I just wasn’t myself.

I’m sorry. I’m really not like that.

If you recognize any of these thoughts, then you might ask yourself, who or what “comes over you” in those moments? If you weren’t yourself, then who were you? Is it possible that one of your internal negotiators took center stage, if only for a minute?

Maybe you went to shake hands with your son at his graduation, and felt tears welling up in your eyes. If you haven’t cried for twenty years, you could ask yourself, “What was that?” Or maybe you approached the nurse’s station every ten minutes, until someone finally came to your mother’s hospital room with painkillers. If you see yourself as an easygoing, laid-back person, you might feel surprised by the insistent tone coming out of your mouth to command the nurse’s attention.

The good news is that our variable nature is adaptive, necessary, and helpful, once understood. Dr. Daniel Siegel, a renowned brain researcher and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, explains it this way in his book Mindsight: “We must accept our multiplicity, the fact that we can show up quite differently in our athletic, intellectual, sexual, spiritual—or many other—states. A heterogeneous collection of states is completely normal in us humans.”

If you’re worried about multiple personalities, fear not. The “multiple minds” phenomenon we’re talking about is universal.

Think about it. Sometimes you go about your day, living like an ordinary Clark Kent. Other days you get the kids out the door, rescue three projects at work, advise your squash partner about his retirement accounts, and help your wife resolve a conflict with her sister. That day you’re a living, breathing Superman. Women feel these swings inside, too. Some days we feel small. We want someone to step up and fight our battles for us like Prim, Katniss Everdeen’s little sister in the Hunger Games. Other days we’re the Bionic Woman, superpowers and all.

Recognizing how this works is not only a sign of positive mental health. It also opens the door to using the range of your potential in targeted ways. Mythologist Sam Keen wrote: “Few of us know the fantastic characters, emotions, perceptions, and demons that inhabit the theaters that are our minds. We are encouraged to tell a single (true) story, construct a consistent character, fix an identity. We are thus defined more by neglected possibilities than by realized ones.” As you get to know your inner negotiators, you’ll expand your profile. Then you’ll get better outcomes, because you’re using strengths and skills you’ve never put to good use before. The Performance Gap you’ve come to accept for years will start to close before your eyes.

Missing Team Members Perform Those New Skills

We all have parts of ourselves that we see, and parts that we don’t. We’ve let some of them into our profile. We’ve left others out.

Why should you care?

Because at the end of the day, if you want to get better results in your life, you need to change what you’re saying and doing now that leads to those outcomes. To create lasting change at work and at home, you need to recruit those members of your inner team who are absent or underutilized.

Said another way, each of the inner negotiators performs certain functions. They specialize in different skill sets. You fall into the Performance Gap again and again because you can’t do skills that belong to negotiators you’ve left behind.

Over time, as you become more familiar with deactivated sides of you, you’ll be amazed at how quickly you can master the skills that belong to the inner negotiators you’ve newly taken on board.

Inner Negotiators Are Personal, and Universal

We’ve talked so far about inner negotiators you can’t see. But what about the ones you do know about? Most of you can think of one or two voices you’re familiar with, for example:

|

The Judge |

The Artist |

|

The Achiever |

The Healer |

|

The Caretaker |

The Survivor |

|

The Rebel |

The Inventor |

|

The Problem-Solver |

The Destroyer |

|

The Gambler |

The Rescuer |

|

The Crisis Manager |

The Mystic |

|

The Seducer |

The Failure |

|

The Teacher |

The Explorer |

|

The Skeptic |

The Activist |

In the privacy of your own mind, your internal negotiators seem idiosyncratic and very personal. After all, they know all of your secrets.

To some extent, they are uniquely your own. Your inner cast of characters reflects what makes you distinctive. That includes things like your role in your family, the place you grew up, your ethnic culture, or your religious upbringing. It also includes things other people can’t see—your hurts, your loves, your experiments and mistakes, your personal triumphs and your private traumas. All of these experiences shape the constellation of voices on your inner team.

At the same time, we share some universal forces with common functions, “characters” who populate our human story. They evoke related themes for many people. Noted psychologist Carl Jung talked about these as “archetypes” that belong to what he called the “collective unconscious.” That means no one needs to teach you the essence of these images—they’re inborn like your DNA.

In other words, you don’t need to “learn” how to pump your heart in your body—you’re born knowing how to make your heart beat. Jung said you also don’t need to learn about core elements of the human experience. You’re born with recognition of archetypes, like Mother and Father, Hero and Villain, Ruler and Servant, Wise Elder and Fool.

We’ve come a long way since Jung. Tremendous work has built on his ideas, such as the pioneering work of Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, whose book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover sharpened our understanding of Jung. Thinkers like Carol Pearson and Caroline Myss have written extensively on archetypes. Other experts created ways of bringing them to life through experience, like my friend and colleague Cliff Barry, who designed a system he calls Shadow Work, and Hal and Sidra Stone, who originated Voice Dialogue. Gestalt. Big Mind. The list goes on.

Across the research, you’ll find some thinkers have moved away from the idea of inborn archetypes. They believe we create personified images out of our life experiences, but they still connect us to the larger human story. They discuss related concepts with fancy-sounding names, like imagoes, introjects, schemas, or personal myths.

I don’t know whether we come into the world recognizing these patterns, or we learn about them during our lives. What I can tell you is this:

■ by the time we reach adulthood, these archetypes or imagoes are alive and well in all of us

■ they shape us in ways we can’t easily see without working at it

■ they play a significant role in why we fall into the Performance Gap

■ with a bit of help, we can see clearly how they influence us and drive our experiences

■ once we recognize how they’re working, we can shift their form and create entirely new possibilities in our leadership and our lives.

Meet the Big Four

Leading mythologist Joseph Campbell described each of us as “a hero with a thousand faces.” I think mastering a thousand faces sounds a bit daunting. If you have all of these different sides of you, how can you even begin to get a hold on them?

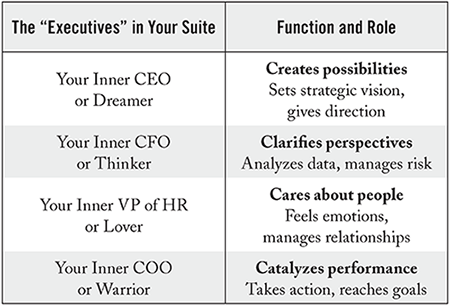

To help people develop as leaders and close their Performance Gap, I focus on a small set of those hundreds of faces. I call the group The Big Four (see Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1

They are:

■ your Dreamer

■ your Thinker

■ your Lover

■ your Warrior

To be sure, any four of Campbell’s “thousand” can’t capture every facet of who you are. Not even close. But that’s not the goal here.

What the Big Four cover is the basic ground you need to succeed at work and at home. By themselves they won’t get you to “self-mastery.” On the flip side, you can’t get to self-mastery without understanding them. The Big Four are universal, and relevant to the way you function every day. They’re also most likely to trip you up if you don’t see them coming.

Since I consult to a lot of businesses, I sometimes describe the Big Four as a leadership team, occupying your internal executive suite:

The Chief Executive Officer: CEO, or Dreamer

The Chief Financial Officer: CFO, or Thinker

The Vice President of Human Resources: The VP of HR, or Lover

The Chief Operating Officer: COO, or Warrior.

Sitting around a conference room table, these leaders would bring their own expertise and priorities to the conversation. If anyone missed the meeting, the team would make decisions that lacked a perspective vital to the company’s success.

Without the CEO, they could miss the bold vision that’s essential to an innovative strategy. No CFO, and the budget collapses. Without HR, the right people don’t get hired or developed. If the COO’s absent, it’s all talk and no action (see Table 2.2).

TABLE 2.2

A business will find itself in trouble if it doesn’t envision possibilities, can’t appreciate a 360-degree perspective, fails to care for its people, or turns in lackluster performance. This is true for you, too.

Linking the inner negotiators to the working world helps clarify the voices they express. It also points to their respective domains of skill and expertise. However, this helps only to a point. The Big Four represent much more than professional titles.

Wanting, thinking, feeling, and doing—these are part of the shared human experience. The Big Four represent your capacity to dream about the future, to analyze and solve problems, to build relationships with people, and to take effective action. How people express the Big Four varies by culture. But the basic functions cross boundaries.

Together the Big Four Lead to Optimal Performance

Whether you’re leading a team or running a household, the sides of you expressed by these inner negotiators help you succeed in different ways.

■ Sometimes you roll up your sleeves and keep working until you finish your memo for a client. Or you cross-check every name on the list and every table assignment before your family reunion, to make sure no one gets left out, or seated next to the wrong cousin. Maybe your business partner calls and asks you to fly to Paris for a one-day meeting—on your daughter’s birthday.

Here, you want your Warrior in the lead.

■ Sometimes you have a family member with special needs—an older parent who can’t live alone anymore, or a sibling who’s confided in you about struggling with addiction. There’s a lot to figure out, like how to pay for assisted living, or how to help your sibling get into recovery while respecting his or her privacy. At work you make judgment calls all the time: about contract terms and conditions; how to comply with regulations; making fair work schedules that divide weekends and holidays among the staff; whether to lower your prices; to name a few.

Here, you need your Thinker at the helm.

■ Sometimes you have the chance to land a valuable new client. To get their business, you need to show that you really understand their business issue and why it matters to them to fix it now. You only have one shot to build rapport and earn their trust. At home you need strong listening skills, too, if you’re talking to your sister whose spouse just walked out, or your co-chair of the annual All-School Dinner who wants to step down.

Here, you want your Lover out in front.

■ Still at other times you need all of your imagination, to plan the most memorable fiftieth-birthday party for your best friend, or design the best costumes ever for the Pirates and Princesses Parade. You need vision to come up with your third career after you “retire.” And a story to tell yourself and your family about why the upcoming move is going to be a grand adventure. At work you need to picture the future: to innovate the products and services that people will want a few years down the line; to hire and develop talent today that you’ll need tomorrow; to inspire your workforce; to refine your strategic direction.

Here, you should call on your Dreamer first.

Become an Equal Opportunity Employer

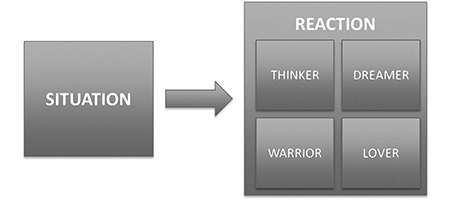

Ideally, you have the Big Four operating within you in balance. Then you can call on each one when the time is right. In reality, very few of us have easy access to all four. In any given situation, all four inner negotiators are available to us in theory. But we’re unlikely to make a real choice that considers all of them. We become increasingly skillful as we call on more of them, and learn to use more of them, comfortably and effectively (see Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.3

As we’ll explore more in the next chapter, we tend to use one or two of the Big Four a lot—they’re lead characters in our profile. We mostly ignore the other ones—they may not figure in our profile at all. Self-mastery involves a process of gathering all four of them together, and practicing how to use their strengths to balance each other.

As I’ve given talks and taught seminars around the world on this material, people grasp fairly quickly the idea of integrating all parts of themselves into their everyday interactions—the inspirational Dreamer; the analytical Thinker; the emotional Lover; and the practical Warrior. As we’ve talked about a lot in this chapter, what’s much harder to get is how this works in practice. People wonder, “How do each of the Big Four work inside of me?”

Trust Me, You Have the Big Four Inside of You

The Big Four can be hard to see in yourself. Like these audiences, you might think to yourself, “Emotional Lover? Not me. Ask my employees.” Or “Analytical Thinker? Tell that to my husband: he thinks I’m nuts because I read the horoscopes.”

I once worked with a rocket scientist who told me he “never feels anything.” I told him I found that hard to believe.

“Really,” he told me. “I don’t have any feelings.”

I remained skeptical.

“Are you married?” I asked.

“Yes, for twenty-eight years.”

“How did you know you wanted to propose if you have no feelings?” I asked.

“That’s easy,” he said. “Because she was the girl of my dreams, and I knew I would go crazy if I couldn’t be with her.”

You might not recognize the Big Four in yourself right away. But they’re in there.

The Big Four and You

For some of you, the way you relate to the Big Four is unmistakable. For others, you’re just starting to think about it: Which of the Big Four have I embraced? Have I left any behind? Am I able to balance them to make good choices and take effective action in my life? Which one do I need to develop the most?

It’s hard to give you a good answer to those questions in a book. If you want a richer picture of your profile, you can take the survey at www.winningfromwithin.com. Just click on “My Big Four Profile.” For now, let’s put a toe in the water with a quick exercise. This might jump-start your reflections—but don’t put too much weight on what you find.

Profile Quiz: Getting a Snapshot

Table 2.4 shows an exchange between two spouses. First, read the comment from “your spouse.” Then read the four possible responses. As you read the choices, imagine that you are the spouse who needs to respond, and ask yourself:

1. If this is me, which sample reply will I give first?

2. Do any of them strike me as “clearly” the most helpful?

3. Do any of them strike me as something I would never say?

Your spouse says: “I really need a vacation. I know we’re broke. But I’m burned out and exhausted. I need to recharge my batteries.”

Your opening response is one of the following:

ONE: “Sounds great. I can see us on a blanket on the beach with drinks in our hands. Shining sun. Lapping waves. Cool breeze. Perfect.”

TWO: “I think we’re over our budget. I don’t know if there’s any surplus we can spend. If we estimate the cost of a long weekend, we can compare the expense to our savings, and then determine what we can afford.”

THREE: “I’m sorry to hear you’re so exhausted. Tell me more: what’s going on with you?”

FOUR: “Well, if you work a bunch of overtime in the next few weeks, and we only eat at home, we can pay down the credit cards. But if we can’t lower the debt dramatically, we can’t go.”

TABLE 2.4

In real life, your response might combine several of these elements. And in real life, these comments might not capture the wording you’d choose. For the purpose of this exercise, focus on the approach more than the exact words, and pick one you might take as your opening reply.

Which response sounds the most like where you would start? Do you like any of them the best? Do you reject any of them outright? Can you identify which negotiator is speaking?

In the first case, you hear the voice of the Dreamer, immediately envisioning the vacation and inspired by the picture of the beach. In the second comment, the Thinker comes through, inclined to look at the numbers and make a rational assessment. In the third reply, the spouse embodies the Lover, empathizing and reaching out to hear more. The fourth response reflects the stance of the Warrior, considering what actions to take toward the goal. The Warrior is also ready to draw the line and say no if needed.

Chances are that you reacted more positively to one or two of these responses. If that’s right, you might think more about those inner negotiators, and whether you favor them over the others in real life. To explore a little more, ask yourself what positive results you get from using those voices frequently. Likewise, think about what possible negative impact you might be getting from doing that.

For instance, if you gravitate naturally to the Dreamer, you might be great at inspiring your teams. On the flip side, if you’re quick to offer your vision at every team meeting, it’s possible you’re not leaving enough room for others to share their vision with the group.

It’s also possible that you reacted negatively to one or two of these approaches. You can ask the same questions of yourself. What benefits am I getting by rejecting this voice? What possible negative impact does it have on me or my life that I’m doing that?

So, for example, let’s say you really didn’t like the voice of the Warrior. Maybe you found it harsh and unfeeling. Maybe you thought the request deserved more brainstorming and problem-solving before jumping to a conclusion.

In your life, you might find good reasons to stay away from this practical, tough-love approach. Maybe you pride yourself on the way your kids always come to you when they need someone to listen. Or you value your reputation in the state bar association as a lawyer who prefers to collaborate. These are great outcomes you’re getting.

At the same time, if you reject the Warrior nine times out of ten, what are you giving up? Maybe those same kids who love to talk to you will turn to other people when they need the cold, hard truth. They don’t trust your feedback, because they know you’re always “supportive.” Those same colleagues might not refer clients to you. Deep down they value a lawyer who’ll fight. They question whether you’ll go the distance if a lawsuit turns ugly.

Every profile has its trade-offs.

If you really wanted to go on that vacation, take care of your spouse, and protect your family’s financial health, you’d be well served to draw on all of the Big Four—at the right time and in the right way. Putting that potential into practice is what closing the Performance Gap is all about.

Are Mother and Father the Same?

For our purposes, we’re not going into detail about variations among archetypes between men and women. Let me acknowledge that differences exist, just like researchers have found some differences in the brains of men and women. Despite not engaging the topic deeply, I’d be remiss not to touch on the gender aspect of inner negotiators at all. If you’re interested, I recommend classic works in this area by Carol Gilligan, Jean Shinoda Bolen, Robert Bly, and Sam Keen. I also suggest you review research from UCLA on different survival responses of women and men.

In my work introducing archetypes to clients from nearly every professional discipline, I can say that gender difference has played a smaller role than this vast area of research would suggest. Let me offer one example.

Do you remember Susan Boyle? She came out of nowhere and captured the world’s attention by singing on television. How did this middle-aged, frumpish lady sing one song on Britain’s Got Talent and become an international superstar overnight?

I’d say it’s because Susan Boyle is both an ordinary woman and a timeless archetype. Don’t we all want people to look beyond our outer blemishes to discover our inner beauty and hidden gifts? Aren’t we all like the frog waiting to be kissed, so everyone can see us rise and stand fully in our nobility?

I’ve witnessed the drive that Susan Boyle taps into—to feel seen and appreciated—in men and women in equal measure. Both men and women also have a part inside that’s drawn to self-destruct. Both are capable of acting The Loyal Friend, and The Betraying Spouse. Both can play The Tyrant, The Martyr, The Victim, or The Savior. Both can play The Virgin, The Whore, or The Saint. Both at times feel needy and powerless; both carry amazing strength and resilience.

Yes, the development journeys of heroes and heroines include different obstacles and unique milestones. At the same time, fundamentally, we’re all human. That’s the perspective I’m taking as we continue our basic exploration.