You are unique, and if that is not fulfilled,

then something has been lost.

—MARTHA GRAHAM

Mark is an engineer working with a team in the high-tech industry. Like many managers, he finds himself torn between the people who report to him, and his boss Stefan, the head of his business unit. Mark and Stefan are in a heated exchange:

|

STEFAN: |

You should never have told the staff about this decision! |

|

MARK: |

I should have talked to you first, yes. But I needed to tell the team before they took irreversible action. |

|

STEFAN: |

That’s absurd! You’ve completely tied our hands and damaged management’s credibility. |

|

MARK: |

Everyone knew something was up, and they won’t trust me if I don’t tell them what’s going on. |

|

STEFAN: |

Well, be glad you have their trust, because I don’t trust you at all! Don’t expect me to come to you for advice again anytime soon. |

As the shouting match erupted in the hallway, Mark’s stomach was in knots. He tried to stay calm. But he was losing his cool. Part of him knew he should play nice. Stefan was his boss, after all. Another part of him wanted to strike.

Mark could picture a tennis match in his own mind, with balls lobbing back and forth across the mental net:

Take a stand against this jerk.

No, be a team player.

No one should treat you like this and get away with it.

Let it go—he isn’t worth making a scene.

Then the conversation in his head grew heated:

Is he kidding?

He thinks I broke the bad news?

He doesn’t get it.

People have been talking about this for weeks!

Stay calm, or this won’t end well.

This is why no one likes you, Stefan—because you’re a bully!

Shut up! He’s still your manager!

Mark finally gave in to his anger. He couldn’t hold his tongue for one more minute.

“If I’m so untrustworthy, why do I have the highest employee loyalty in the company?” Mark asked Stefan flatly. “Frankly, I’d be glad for you to not come to me for advice. With any luck, I won’t need to talk to you at all. You text me, and I’ll reply. Consider my door closed.”

When he got back to his office, Mark felt relieved. It was good to tell Stefan how he really felt.

But within minutes, a familiar sense of regret washed over him. He knew he should have kept his mouth shut, at least until he calmed down. Telling his boss he’d prefer never to talk to him again wasn’t the greatest idea. Yet time and again, in those hot moments of confrontation, he just couldn’t keep his cool.

If We Don’t Explode, We Withdraw

At the other end of the spectrum, there’s my former student Rafiq. Unlike Mark, Rafiq didn’t explode. In fact, he could hardly speak at all.

For three years, Rafiq had studied at Harvard Law School. After graduation, he’d planned to return to Pakistan and his family. Much to his surprise, while at Harvard, Rafiq fell in love with an American woman from the Midwest. Their relationship was a source of joy, but also dread. Rafiq knew that one day he’d have to tell his mother that he wouldn’t be returning to Pakistan as she assumed. He planned to marry Stacy and live in the United States.

On several occasions, the conversation almost happened. He’d phone home to discuss graduation plans since his mother, father, and extended family were all coming to America for the ceremony. He’d gone over and over it in his head—what he would say, the firm but gentle tone he would take. He visualized the conversation ending well.

But then the real moment would arrive, and he would freeze.

“When are you coming home?” his mother would ask. Rafiq would say nothing. “You’d better buy a plane ticket soon before the fares go up,” his mother continued. More silence.

During these actual conversations with his mother, part of Rafiq urged, “Go on, tell Mom the truth.” But before he could open his mouth, the counter-point emerged: “No! It will kill her.” With each of his mother’s questions, he felt the weight of her expectations. Waves of anguish accompanied opposing thoughts: “You have to tell her sometime,” followed by, “Keep quiet. You’ll break her heart.”

Rafiq wanted to be honest with his mother about his plans to stay in America—he knew he would have to, eventually. But he continued to teeter on the precipice of telling the truth. He deferred questions about plane tickets for later, not even fully aware of all the reasons why, but knowing that he couldn’t bring himself to tell her. Not today.

Succeed from the Inside Out

For many years at the Harvard Negotiation Project, my peers and I taught an Executive Education program in the summer. At the highpoint of the seminar, we ran an exercise to help people develop interpersonal skills. For this special session, we assigned one instructor to every three delegates, in order to provide a high level of individual coaching.

Workshop participants brought a real negotiation challenge from their lives, and we worked with them in trios to help each person improve in their chosen scenario. This all worked just fine, until one day, when a member of my trio was a Supreme Court justice.

Nothing had prepared me to run this high-stakes exercise with such a prominent person. This intimidating seventy-five-year-old gentleman had served on the High Court of his country for the previous thirty-five years.

Before his turn, I strained to imagine the kind of negotiation he would pick to get my advice. Would it involve confrontations with his fellow justices over the rule of law? Do people like him negotiate with the prime minister, I wondered, or members of Parliament? When the time came for his exercise, the judge described a difficult situation that had haunted him for decades.

“Every day for fifty years my wife has picked out my tie,” he told me. “I hate that. I can dress myself. Why does she do that?”

I was stunned. This was the big issue that kept him up at night? I asked the obvious question.

“Have you ever told your wife that you prefer to choose your own tie?”

“That’s exactly my problem,” he said. “No matter how many times I rehearse it in my head, I just can’t bring myself to tell her.”

After years of pondering the same question, something clicked. I got it.

Mark, Rafiq, and the High Court judge are smart people. They’re honest people. They know what makes communication work. Yet they betray themselves: by not holding their ground gracefully, by not telling the truth, and by not standing their ground while also protecting their important relationships.

Usually in the communication skills exercise I did with the Supreme Court judge, we practiced lines people could say when they returned to “real life.” But this time, suggesting to this towering figure that he rehearse the phrase “could you please not pick out my tie” seemed ridiculous. He was an exceedingly powerful person, a man who’d given orders for decades from the bench, issuing opinions that impacted a nation. He didn’t need help with assertiveness skills.

So, practicing behavior was not going to help. He knew the words he could say. The nut to crack was whatever stood in his way from actually saying them.

Working with the justice that day opened my eyes to the problem in a whole new way. Like others before him, when it came to the conversation that truly challenged him, he couldn’t say what he meant, or get what he wanted. But for the first time I saw clearly why focusing on behavior wasn’t the answer.

Beyond the shadow of a doubt, this person possessed the skills that he needed to meet his challenge. The way to help him succeed was to shift something inside him, to work with the voice that told him not to say anything. If he got the green light from that voice inside, he’d have no problem finding the words to talk with his wife. And that is indeed what happened.

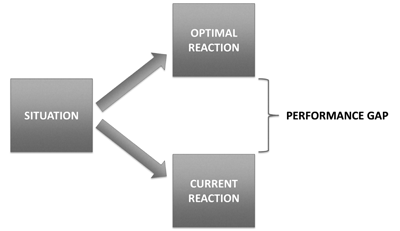

Your Current Reaction vs. Your Optimal Reaction

Once I had this insight, I saw the phenomenon everywhere. It turns out that most people find a disparity between what they know they should say and do to behave successfully—their optimal reaction—and what they actually do in daily life—their current reaction. I call this phenomenon The Performance Gap (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

It doesn’t matter how accomplished you are. Anyone can fall into the Performance Gap. The fact that you’re respected in your career, have a high IQ, or are an eloquent communicator doesn’t necessarily matter. You aren’t mostly falling into the Performance Gap because your problem is beyond your skill set. You’re likely stumbling because of what’s going on inside of you. You’re getting in your own way without even realizing it.

Going Left When We Meant to Go Right

How often do you plan to do one thing, but then in the moment, you do something else?

■ Do you ever plan to listen to your partner, but find yourself yelling—or shutting down—instead?

■ Do you ever intend to collaborate with other people, but then get rigid and stuck in your opinions?

■ Do you ever become defensive or reactive, when you want to keep your cool?

■ Do you say yes when you want to say no?

■ Do you say things and later wish you hadn’t?

■ Do you ever sit quietly, wishing you would speak up or take a stand?

■ Are you tempted to break away from everyone’s expectations, but feel too scared or “too responsible” to rock the boat?

■ Do you ever feel at odds with your passion and life purpose?

You may practice a dialogue on the drive to work. You can see yourself saying just the right thing. But it’s often not enough, no matter how senior or how experienced you are. Steps like these didn’t work for the High Court justice. And it hasn’t worked for thousands of people I’ve advised around the world.

Why, like Mark and Rafiq, do we fall victim to the Performance Gap again and again? Where do we go wrong? And most important, what can we do to change these outcomes?

One obvious answer is to learn better skills. With a stronger toolbox, you’d get the results, the process, and the relationships that you want. Right?

Actually, no. If you want lasting change, it doesn’t work this way much of the time. Most people think that learning new skills is the answer. It isn’t—at least not by itself. As my mother knew, you need more than a better toolbox.

New Skills Don’t Come from Just Learning Behaviors

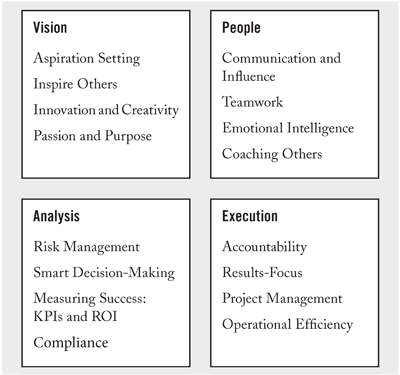

As I consult to companies across multiple industries, I’m struck by how many of them apply “competency grids” to their leaders and general workforce. It seems virtually everyone needs a way to measure the potential and performance of their people. Here’s an example of the kind of grid I’m talking about, listing the “competencies” that people will get measured by (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2

Since they hold people accountable to perform these competencies, companies need to build capability in their leaders and workforce to do them. So they routinely send their people through training to teach them the skills required to perform these competencies.

But remember Mark, Rafiq, and the judge? Learning the behaviors of leaders doesn’t translate into performing the practices of leadership. To generate real change—to see new behavior and get new results that last over time—you need to activate something inside you that enables you to perform the skill.

If you do that, new behavior will come naturally. If you don’t, when the pressure’s on and the stakes are high, you’re unlikely to see new behavior outside of the seminar room.

Taking My Own Medicine

While I researched this book on creating lasting change, I went through a personal transition that gave me a look at “change” from up close.

My life was stable if predictable: I’d lived outside of Cambridge, Massachusetts, for nearly twenty years. I’d remained in the same career throughout those years. I ate in the same Chinese restaurant, went to the same movie theater, and belonged to the same synagogue. I lived fifteen minutes from my sister.

Then, in what felt like the blink of an eye, I fell in love, got married, wed a divorced man from The Netherlands, moved to Amsterdam to live with my new husband, Bernardus, and to live near his son, became a stepmother to a little boy who speaks no English, and landed in a foreign country with no family or friends.

If I wasn’t an expert on change before, I am now.

Before coming to live in The Netherlands, I saw myself as a strong, confident, resourceful person. In fact, if you’d asked me to choose one word to describe myself, I might’ve chosen self-reliant.

A downside of my personal profile is that I couldn’t easily ask for help. But that wasn’t too bad. I didn’t like “needy” people much anyway, and didn’t want to be one of them. Indeed, as the youngest of four, I’d learned early about the folly of weakness. I’m told that as of three years old, I described myself as “a tough cookie.”

Relocating from the United States to Western Europe involves a punishing illusion: everything appears to be basically the same, when it is, in fact, just different enough that a formerly competent person can do nothing. And I mean nothing.

When I first arrived last year, I felt overwhelmed by my new situation. I figured that doing some “normal” things around the house would make me feel—well, normal. So I headed upstairs with a basket of laundry.

Kreukherstellend and Overhemden

To start with, I couldn’t figure out how to turn the machine on. And try as I might, I couldn’t get the door to open to put in any clothes. When I did triumph over the washing machine door, I faced the following panel of choices:

■ Witte was/Bonte was

■ Voorwas

■ Kreukherstellend

■ Overhemden

Are you kidding me?

Laundry was not going to work as my “comfort” activity.

So I turned to other presumably familiar activities to find solid ground: things like making coffee, or roasting a chicken.

No dice.

I couldn’t figure out the coffeemaker if my life depended on it. All I wanted was a plain old Mr. Coffee machine. But here they take coffee so seriously. Everyone has a cappuccino machine, or—as in the house I moved into—one that makes espresso. I’m not sure at that time I even knew the difference between cappuccino and espresso, but I’ll tell you one thing they have in common. I cannot make either one of them in a European, fancy coffee-making device.

Roasting the chicken was out of the question. In our house in The Netherlands, we don’t have an oven. Seriously. We have a microwave, but not something you’d use to roast a chicken. Apparently, “everyone” here cooks on the stovetop. Of course, I could warm up my coffee in the microwave. But that would have required success where I was already an abject failure, as you know.

I was starting to break down. And I was out of ideas.

I finally called a friend in the States, and she had the most annoying thing to say.

“Maybe life has brought you to The Netherlands to learn about your vulnerability.”

“My what?” I asked in disbelief.

“You’re always the strong one, cooking up visions and making things happen. Now you can’t make a cup of coffee. Maybe you’re on a journey to discover a new side of yourself, one you don’t see very often. The part of you that feels vulnerable.”

I thought, “This is what I get when I call my friend? Some friend!”

And she really was.

Integrating Our Hidden Sides

Closes the Performance Gap

The past year of struggle, minor successes, and seemingly infinite confusion has forced me to deal with the Vulnerable Erica. Not something I admit lightly. But I had nowhere to hide.

The irony is that I teach my clients to look for new sides of themselves, to tap inner resources they haven’t discovered. I assure them this is productive and meaningful, that it will improve their lives at work and at home. I also say that such exploration and discovery will build power in their center, the inner core that gives them strength and capacity for skillful action.

Now I was taking a dose of my own medicine.

My Year of Living Vulnerably reinforced several points that we’ll explore throughout this book:

1. We are more multi-faceted than we realize.

I’d defined myself narrowly, both to the world, and to myself.

2. We pick parts of ourselves to define who we are.

Based on what I saw as my strengths, I’d defined myself as a highly competent woman who could do it all on her own.

3. The identities we form have some truth to them.

I am generally a capable and resourceful person. In most situations I feel confident. I like to initiate things and make them happen.

4. Yet, they don’t tell the full truth. We create profiles of ourselves by elevating certain elements of who we are and leaving others behind. That distorts the full truth.

I am vulnerable as well as powerful.

5. The identity we show the world, and ourselves, isn’t necessarily false. But it isn’t fully true. What we amplify and diminish in our profile leads to our Performance Gap. That keeps us from fulfilling our potential in all areas of our lives.

If people, starting with me, see only my powerful side, they don’t see all of me. Trouble is, the parts that I’ve deleted from my profile have a lot to offer. Like my vulnerable side, who knows how to ask for help. I can only exercise that skill when I integrate that missing piece into my profile.

6. We gain something when we recognize a part of ourselves that’s missing from our profile—the way we define who we are—and expand it to include what we left out. We also gain by right-sizing parts of our profile that we express now in excess. Doing both gives us a sense of centeredness. And that leads straight to high performance.

I can make coffee in The Netherlands now. Believe it or not, I can choose on my own between Bonte Was and Overhemden. Bernardus’ family is part of my family. And Bernardus’ son, whom we call the Little Dude, is teaching me to speak Dutch. That’s all because I learned to ask for help. To let people see that I’m struggling. And to accept that while I’m powerful to my core, I am vulnerable to my core, too.

7. Lasting change doesn’t happen overnight.

Yes, I can do the laundry. Yes, I love Bernardus’ family. But I have all of one friend in The Netherlands. We haven’t found a synagogue yet. I have no familiar restaurants. No idea where to find a movie theater. Stepparenting is a world unto itself. I miss my sisters terribly. I long for my house, my friends, and people speaking English. I’d be stretching it to say that Amsterdam feels like “home.” It’s not easy, but it’s the voyage I’m on.

The Bottom Line

Ideally, we’d like to deliver our optimal reactions. Most of the time, we don’t. Instead, we fall into the Performance Gap.

This happens in part because of who we tell ourselves we are—the profile we hold that defines us. It also comes from disconnecting from the strengths and centeredness at our core. To close your Performance Gap, you need to look closely at your current profile, and learn to develop it. Your profile can adjust—a little here, a little there—so it can serve you and the world in whatever circumstances you’re living in now. Leading and living in a centered way will enable that adaptation.

The Winning from Within method of balancing your profile and connecting to your core isn’t about my adventure to a new land. It’s about the voyage we’re all on: to stretch and grow, to live fully, to figure out who on earth we really are. It’s a method for waking up to the wide range of our experiences, both out there in the world as well as in our inner lives. This voyage is both joyful and painful. But ultimately, we want to water the seeds of possibility that are dormant within us. That’s how we live and lead from our full power, our full potential, our full beauty and grace. It’s how we find our way home.

Appreciating the interplay of our internal experience and the world we see around us is also central to leading wisely and fostering lasting change. Madeleine Albright expressed this well when she said, “Opportunities for leadership are all around us. The capacity for leadership is deep within us.” From centuries-old philosophy to contemporary physics, we find this nexus: of inner and outer; microcosm and macrocosm; heaven and earth; immanence and transcendence. In the language of my lineage, Kabbalah: as above, so below. From different directions we come back to the mirror between the grandeur of the universe and the wonder of being human.

This wisdom is driving a new conversation about developing leaders because our times demand it. It’s hard to miss that we’re living through massive change on a global level that impacts each of us on a direct level. Whether you’re coaching a local team, working at a medical clinic, running a law firm or a nonprofit. If you’re trading stocks, working in government, serving meals, attending to passengers, or flying the plane. If you go to school, write blogs, make movies, do research, give lessons. If you counsel or nurse or teach. The deal is the same. You’ll find success and satisfaction from contributing to the world around you with the full breadth of your inner resources. No matter what you do.

You’ll discover that navigating the bumpy road outside gets easier when you can tap the innate wisdom at your core. Indeed, as you get to know yourself from the inside out, you learn to your surprise that some of the bumps out there actually reflect the ones in here. Paradoxically, you can ease your way through the world outside by engaging, embracing, and integrating more of yourself on the inside.

Workshop participants ask me what I mean when I talk about integrating more of you “on the inside.” I say, “Think about everything that happens in you from the neck down. How much attention do you pay to all of that?” I don’t mean you should forget about your head. But the question helps draw attention to embracing more of what’s going on inside of you.

All of that starts with seeing and expanding your profile, the story you tell yourself about who you are. Broadening your profile is what we’ll look at next, in chapter 2.