Governance Structures

—John Maynard Keynes

The issues we have so far discussed and their implementation are all subject to the structure of governance you select. Surprisingly, the structure you select is highly predictive of your success. While there isn’t a “one size fits all” governance structure, we will focus on four primary models that are in vogue with many institutions and discuss a few variations within each model.

The first and simplest model is what we will call the DIY Model. In this model the board, or a subset of the board (the investment committee or even the CFO), manages, governs, and makes all investment-related decisions. This model is suited for organizations with straightforward investment objectives and policies, and minimal assets (less than $10 million).

The second governance model is the Traditional Model, where the board or another entity (e.g., the investment committee or CFO) will supplement their work with an investment consultant. As an institution’s size and the complexity of the investment strategy increases, institutions often look for additional help with their investments, and hiring an investment consultant is a common solution.

A third governance structure, the Internal Model, is where the governing body works in tandem with internal investment staff to carry out the mission of the organization.

The fourth and final governance model we will call the Contracted Model. Here, the governing body works with a contracted external investment team. The contracted investment office is responsible for all the same tasks that an internal investment office normally would do. The only obvious difference is they share some of their time with a small number of other clients. This would be called “outsourcing” in just about any other industry, but in the institutional investment world, the word “outsourcing” is used differently.

Depending on the complexity of the organization and investment program, and size of assets, each governance structure can incorporate many committees and individuals that play a role within the structure. For example, an organization that is implementing the Internal Model, which relies on an in-house investment officer, can also employ an investment consultant or contracted investment office if desired, based on the investment officer’s skills and scope. These decisions on how to structure the governance model, and in particular how roles and responsibilities will be delegated, are an important responsibility of the board.

Ultimately, the success or failure of an investment program will fall on the board, so getting the right players onto the board and structures in place is critical. There are obviously many decisions a board must make while constructing their governance structure. Some of these decisions include which groups or committees should be established, who will take on each responsibility, what level of involvement each group will encounter, and how the committee will be constructed. To further illustrate this point, the following are a series of tables (one for each governance model) that illustrates the potential groups and individuals that are necessary within each model, which groups and individuals are optional, and the expected level of involvement for the various participants.

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Required in Governance Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

The Board |

Very High |

Yes |

|

Investment Committee |

Very High |

Optional |

|

Investment Consultant |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

Table 6-2. Traditonal Model

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Required in Governance Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

The Board |

Moderate |

Yes |

|

Investment Committee |

Moderate to High |

Optional |

|

Investment Consultant |

Moderate to High |

Yes |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Required in Governance Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

The Board |

Low to Moderate |

Yes |

|

Investment Committee |

Moderate to High |

Optional |

|

Investment Consultant |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

High |

Yes |

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Required in Governance Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

The Board |

Low to Moderate |

Yes |

|

Investment Committee |

Low to Moderate |

Optional |

|

Investment Consultant |

Zero |

No |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Very High |

Yes |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

Zero |

Not used |

Irrespective of which committees and groups the board ultimately elects to include, the board must clearly declare the governance purpose for each body to ensure all roles, responsibilities and authorities are established well in advance. Any and all changes must be clearly communicated to all participants and decision-makers.

In the proceeding sections, we will discuss each of the governance models in further detail. Specifically, we will discuss how the chain of command can and ought to be structured, the key decision-makers within each model, the roles and responsibilities for various decision makers, and the benefits and shortcomings of each governance model.

The simplest and most basic governance structure is the DIY Model. In this particular structure, and as the name suggests, the board opts to be the sole decision-making body. As such, an increased amount of time must be spent by the board on investment-related decisions.

DIY Model Structure

Being the sole and ultimate decision-maker, the board has a number of issues and responsibilities that must be ironed out. Highest on their priority list is formulating an investment policy. Secondarily, they must determine how to implement the policy. The board must decide who will lead the efforts, and how they (internally) will hold one another accountable. Other discussions the board must consider are: Who will be responsible for performing investment manager due diligence? How will asset allocation targets be established? What liquidity is needed? What asset classes are investable? Who will be the custodian? Who will be the broker? How will best execution amongst brokers (implicit vs. explicit costs) be monitored? How will the board handle large market swings? Will the board tilt the portfolio to take advantage of market opportunities? Who will furnish performance reports? How often will performance reports be produced? How is risk being defined (volatility, probability of failure, drawdown, etc.)? What will spark a change in investments? Will external investment managers be used? Will the money be managed internally? How will future cash flows impact the portfolio? How often will the portfolio be monitored? Who will offer tax guidance? What is the appropriate time horizon? What legal or bond covenants must be considered?

Although the above list isn’t all-inclusive, it should be fairly apparent that the number of potential issues and responsibilities that must be accounted for could cause an unnecessary burden on the board.

For smaller institutions, or institutions with a board unwilling to relinquish control, that want one or perhaps two mutual funds, or maybe just want to leave the money with the bank or someone’s personal stock broker, this may be functional but not necessarily a “best practice.” If the institution has a limited asset base (less than $10 million) and a fairly straightforward investment program (perhaps all the money is at the bank), this governance structure may make sense, but if not, it’s likely an alternative structure would be a wiser fiduciary solution. For a fund that is sizeable or complex, the board may in fact be doing their institution a disservice by doing it themselves.

One of the main issues with the DIY governance model is time. Board members already have a finite amount of time, and the additional responsibilities that are required to manage the investment portfolio only add to their workload. The board can elect to set up a separate committee (an investment committee) to help with establishing investment policies and implementation, although, again, the onus still falls on the organization to establish and execute policy.

Implementation is time-consuming, and monitoring a portfolio on a quarterly basis as opposed to daily can leave it vulnerable. One of the most important value-adds that external advisors bring is their resources, specifically the time that is needed to proactively screen money managers, evaluate various investment opportunities, research asset classes, and monitor the risk of the portfolio.

Another drawback of the DIY Model is investment knowledge, or lack thereof. Even though there may be some trustees who have some personal investment experience, managing an entire portfolio (across multiple asset classes) is vastly different than managing a stock portfolio or personal 401k plan. Time is still another issue. Based on your institution’s own circumstances, if you believe implementing the DIY Model gives your institution the best chance for success, you should ensure that your board meetings do not turn into investment club meetings. Instead, roles and responsibilities should be assigned to different members prior to discussing investments. For example, the chairman of the board should set the meeting agenda to include items such as evaluation of the managers, fund performance, rebalancing activities, and any suggested changes to the portfolio. To minimize groupthink, the governing body should consist of five to seven members, with varying backgrounds and skill sets. Members should have term limits to ensure fresh ideas are being discussed and evaluated. For an institution implementing the DIY Model, the board must be cognizant of the fiduciary role they assume as actors on behalf of their institution, particularly their role in developing and executing investment policy. Overseeing implementation of the investment policy is one of the largest challenges facing a board that chooses to use the DIY Model. Unless your investment program is simple, and your investable assets are less than $10 million, it’s our belief that you’d be better served employing an alternative governance structure, given the amount of time and resources that are required to manage the investment program.

|

Option 1 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Accountability |

|

The Board |

Low to Moderate |

Very High |

|

Investment Committee |

Moderate |

Very High |

|

Investment Consultant |

High |

Zero |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Zero |

Zero |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

Zero |

Zero |

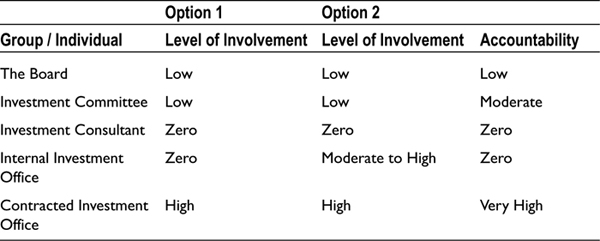

Although some organizations would argue the Traditional Model is a bit dated (and I would agree), the Traditional Model does provide for an outside perspective and added resources. Using a Traditional Model, an organization will work with an investment consultant, whose main task is to act as an external advisor establishing and implementing the investment policy. While an investment committee is not a requirement within this governance structure, most organizations will typically set up a committee to help monitor the investment consultant, enabling the board time to focus on strategy and policy decisions as opposed to investment implementation decisions.

Traditional Model Structure

George Russell, founder of Russell investments, pioneered the Traditional Model when, in 1969, he made a pitch to J.C. Penny to demonstrate the value of money manager evaluation. During his conversation with J.C. Penny, he convinced them that there was indeed value in evaluating and recommending money managers, and J.C. Penny in turn agreed to hire him (his first pension fund consulting client).

Over the past forty five years or so, the industry has changed dramatically. Historically, investment consultants, working in conjunction with the governing body, provided unbiased opinions regarding asset classes and manager selection; the service George Russell pitched to J.C. Penny. Today, though, it’s extremely difficult to categorize all investment consultants as the same because their roles, responsibilities, and business models have evolved over time. In 2005, the SEC described the activities of investment consultants as: (1) identifying investment objectives and restrictions; (2) allocating plan assets to various objectives; (3) selecting money managers to manage plan assets in ways designed to achieve objectives; (4) selecting mutual funds that plan participants can choose as their funding vehicles; (5) monitoring performance of money managers and mutual funds and making recommendations for changes; and (6) selecting other service providers, such as custodians, administrators and broker-dealers, showing the wide range of services offered by consultants. This enables the governing body to seek out only those investment consultants who can effectively meet their needs.

Investment consultants often help organizations establish their investment policy, which is done through the creation of an investment policy statement. The investment consultant addresses return objectives, risk tolerance, acceptable asset classes, and portfolio rebalancing tactics when creating the policy statement. An investment consultant could also assist in the implementation stage, including help with investment manager due diligence, performance reporting, target asset allocation, and guidelines for asset allocation rebalancing.

While most consultants may offer investment manager due diligence and performance-reporting services, there are few who will make an actual hire-or-fire decision as it pertains to money managers. For that reason, many institutions operating with the Traditional Model still must rely on the governing body to implement the investment strategy by hiring and firing managers, implementing asset allocation decisions, and rebalancing. This, like the DIY Model, puts the responsibility for performance back in the hands of the governing body. This is one of the main pitfalls of investment consultants; some have described the role of a consultant as an “insurance policy.”

This shouldn’t come as a shock, because as their name implies, investment consultants do just what is expected—they consult. They offer multiple investment managers when presenting a particular investment idea to avoid accountability, and are often anything but transparent. The accountability and transparency issues (or lack thereof), has recently gained traction within the investment community. In fact, it was even highlighted by Andrew Kirton, global chief investment officer at Mercer. Mr. Kirton was quoted in September 2013 in Pensions & Investments magazine, saying “It’s in our clients’ interest to have the level of transparency that we have [none]. We’re not forced by marketing purposes to give advice we think isn’t in their best interest due to polishing numbers that makes us look better in a survey.” Definitely a rationalization of hiding how well they do or don’t do their jobs.

Lack of performance track records and poor performance are reasons so many institutions are looking for help elsewhere. Dr. Howard Jones and his colleagues, Professor Tim Jenkinson and Dr. Jose Vicente Martinez of Oxford University, examined the recommendations of investment consultants from 1999 to 2011 to determine whether or not they added value to a portfolio’s performance adjusted for risk. According to Dr. Jones, “The analysis finds no evidence that the recommendations of the investment consultant for these U.S. equity products enabled investors to outperform their benchmarks or generate alpha.”1 The study found that, on average, the consultants’ recommendations underperformed their benchmarks by about one percent. Lack of performance track record, or an underwhelming track record, is not the only drawback to the Traditional Model.

Another major drawback is the numerous conflicts of interest that exist between investment consultants and investment managers. A study by Jay Youngdahl of Harvard University, “Investment Consultants and Institutional Corruption,” addressed some of these conflicts of interest and other issues surrounding investment consultants. He found that, due to investment consultants’ position within the industry, they at times can and will collude with investment managers whereby the investment managers are recommended to the organization and in return the investment manager provides some remuneration for the consultant’s recommendation. Because so many institutions use investment consultants as their de-facto investment expert, investment consultants have increasingly gained power through the accumulation of clients and assets. This in turn makes them especially important from the vantage point of an investment manager, because they are the gatekeepers to the institutions who are the true asset owners. Therefore, it’s not uncommon to see investment managers wine, dine, send gifts, or offer free retreats to investment consultants.

That’s not to say the Traditional Model is entirely bad or that all investment consultants are corrupt. The Traditional Model does add an additonal layer of oversight and provides (perceived) safety to those board members that are worried about being fiduciaries. The most sought-after service offered by investment consultants is their managerial due diligence, often embodied by a platform of managers. A manager platform is a repository of investment managers that the investment consultant has already vetted and evaluated at the same level of diligence. The investment managers who occupy the consultant’s manager platform are currently being recommended to clients by the consultant. Each manager platform is different; some managers might be on the platform to fit a specific style box (e.g., large cap value, large cap growth, mid cap value, mid cap growth), while others might be on the platform because of the investment type (fixed income, private equity, hedge fund). Being on a platform is highly lucrative for the manager and reduces the consultant’s need to spend time or money on the diligence of many different managers.

Contracted investment offices have been used for years because of their flexibility and the customized nature of their service. Unlike investment consultants, for whom economies of scale lead to their own business success, contracted investment offices are successful for their member clients when working with a handful of clients. This leads to a much higher level of client service, more customized solutions, and advocacy for the fund that is not commonly found in the Traditional Model. The business is all about the client.

A fairly recent phenomenon is the increased use of contracted investment office in conjunction with an internal investment office. More public and private pension plans are seeking the expertise of a contracted investment officer not found with the in-house investment office. They leave the investment part mostly to the contract office and use the in-house office to interface with the stakeholders. It’s not uncommon for an internal investment office to be run by an executive director and to not be fully equipped with the skill sets that span the spectrum of investments.

In terms of structuring a Contracted Model, an organization has two basic options. One is to work directly with the contracted investment office (most common), and the other is to outsource a portion of the investment program to the contracted investment office while simultaneously keeping the rest in-house with the internal investment office.

One of the main draws of the Contracted Models that contracted investment offices can work with varying levels of discretion and fiduciary roles. Specifically, contracted investment offices are able to help organizations in a similar capacity as an internal investment office. This includes assisting not only in meeting the return objectives, but also with developing funding requirements, cash-flow needs, volatility concerns, audit support, and sometimes even corporate finance decisions.

Working with a varying level of discretion depending on the board’s preferences, the contracted investment office can develop an investment policy statement, implement the investment program, perform investment manager due diligence, make asset allocation recommendations, establish risk metrics, create performance reports, conduct research on various asset classes, assist in audit support, review all limited partnership agreements, advise on custodial and brokerage accounts, monitor liquidity, and tilt the portfolio given various market opportunities.

Institutions that can’t afford, or choose not to afford, to use an internal office are able to replicate an internal investment office at a fraction of the cost. Institutions chose this approach because they can get experienced and highly productive investors at a reasonable cost.

|

Group / Individual |

Level of Involvement |

Required in Governance Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

The Board |

Low |

Yes |

|

Investment Committee |

Moderate |

Yes |

|

Investment Consultant |

Zero |

No |

|

Internal Investment Office |

Very High |

Yes |

|

Contracted Investment Office |

Zero |

No |

Internal Model Structure

The only real difference between the Internal Model and the Contracted Model is that the investment office is internal, with actual employees rather than contract employees. This internal investment office would include a chief investment officer and perhaps a staff, although that’s not a requirement. The internal investment office would manage all the day-to-day nuances of the investment management program, including manager performance, investment manager due diligence, asset allocations, portfolio tilts, portfolio risk, and liquidity.

This internal structure allows the board and investment committee the time required to focus on oversight. Oversight includes constructing reasonable evaluation metrics so the internal investment office is held accountable for their investment decisions. In conjunction with the internal investment office, the governing body needs to set the investment policies at the onset of the investment program, so that the risk and return objectives are defined and established. Another decision is discretion. Investment discretion, in any of the governance models, is not necessarily black and white; it’s more likely to be a shade of gray. Internal investment offices can work with varying levels of discretion, but this should be established well in advance so there are no questions as to who holds accountability for investment performance. Delegating full autonomy and discretion to the internal investment office places the accountability solely on the internal investment office. This accountability allows the governing body to quickly implement change if the internal investment office is not pulling their weight.

The only shortcoming of the Internal Model is cost. According to some in the industry, it isn’t economically feasible to have an internal investment office until an organization reaches $2 billion or so in assets, and becomes a necessity after about $5 billion. Cost alone, or even assets, shouldn’t determine the direction the board takes; control and perhaps secrecy are other factors.

As one of many variations on a theme, the Internal Model can also incorporate an investment consultant or contracted investment office in situations where (1) the governing body is looking for additional data points; (2) costs are an issue and hiring additional staff is a political nightmare; and (3) the internal investment office doesn’t have the skill set or expertise in specialized areas such as hedge funds, private equity, or the like.

Recap

The Internal Model is the gold standard, and its success is dependent on the quality of the individuals employed. Cost is the factor most at issue for a board; can they, or are they willing to, afford one and its corollary: can they pay enough to get experience? Following that closely is the Contracted Model, which has nearly the same advantages as the Internal Model at a fraction of the cost. It is slightly less—an advocate and needs slightly more supervision. Because their use is observable in increased portfolio returns and in board satisfaction, these are the models we favor.

So what makes a good investment committee? Good investment committees debate issues and make recommendations that are framed openly and transparently. As Catherine D. Gordon and Karin Peterson LaBarge of Vanguard wrote in May 2010 in “Investment Committees: Vanguard’s View of Best Practices,” the best investment committee practices are:

- Establish an explicit understanding of a portfolio’s purpose and objective and a clear definition of success in determining whether the portfolio fulfills that purpose and meets that objective.

- Create a charter outlining the roles and responsibilities of committee members, support staff, and—if applicable—consultants and outsourced CIO.

- Establish a clear investment strategy that includes a reasonable set of assumptions about a sponsoring organization’s risk tolerance and expected returns.

- Establish a straightforward process for hiring managers to implement that investment strategy and for identifying the circumstances under which such relationships can be terminated.

- Act with common sense and discipline.

As the world of finance continues its exponential path of increased complexity, determining lines of authority, delegating roles and responsibilities, and implementing oversight policies are essential to success. This process and structure we will call governance. The actual definition of governance can be summed up as “the processes, structures and organizational traditions that determine how power is exercised, how stakeholders have their say, how decisions are taken and how decision-makers are held accountable.”

______________

1Tim Jenkinson, Howard Jones, and Jose Vicente Martinez, “Picking Winners? Investment Consultants’ Recommendations of Fund Managers,” Journal of Finance, Forthcoming (2014), http://ssrn.com/abstract=2327042.