CHAPTER FOUR

LEARNING TO SAY NO

BUILDING WORKSHEETS

Writing a lyric is like getting a gig: If you're grateful for any idea that comes along, you're probably not getting the best stuff. But if you have lots of legitimate choices, you won't end up playing six hours in Bangor, Maine, for twenty bucks. Look at it this way: The more often you can say no, the better your gigs get. That's why I suggest that you learn to build a worksheet — a specialized tool for brainstorming that produces bathtubs full of ideas and, at the same time, tailors the ideas specifically for a lyric.

Simply, a worksheet contains two things: a list of key ideas and a list of rhymes for each one. There are three stages to building a worksheet.

1. FOCUS YOUR LYRIC IDEA AS CLEARLY AS YOU CAN

Let's say you want to write about homelessness. Sometimes, you'll start the lyric from an emotion: “That old homeless woman with everything she owns in a shopping cart really touches me. I want to write a song about her.” Sometimes you'll write from a cold, calculated idea: “I'm tired of writing love songs. I want to do one on a serious subject, maybe homelessness.” Or, you may write from a title you like, maybe “Risky Business.” Then the trick is to find an interesting angle on it, perhaps: “What do you do for a living?” “I survive on the streets.” “That's a pretty risky business.”

In each case, it's up to you to find the angle, brainstorm the idea, and create the world the idea will live in. Since you always bring your unique perspective to each experience, you will have something interesting to offer. But you'll have to look at enough ideas to find the best perspective.

Object writing is the key to developing choices. You must dive into your vaults of sense material — those unique and secret places — to find out what images you've stored away, in the present example, around the idea of homelessness.

EXERCISE 9

Stop reading, get out a pen, and dive into homelessness for ten minutes. Stay sense-bound and very specific. How do you connect to the idea? Did you ever get lost in the woods as a child? Run away from home? Sleep in a car in New York?

Now, did you find an expressive image, like a broken wheel on a homeless woman's shopping cart, that can serve as a metaphor — a vehicle to carry your feelings? Did you see some situation, like your parents fighting, that seems to connect you with her situation? These expressive objects or situations are what T.S. Eliot calls “objective correlatives” — objects anyone can touch, smell, and see that correlate with the emotion you want to express. Broken wheels or parents fighting work nicely as objective correlatives.

Even if you find ideas that work well, keep looking a while longer. When you find a good idea, there is usually a bunch more behind it. (The gig opening for Aerosmith could be the next offer.) Jot down your good ideas on a separate sheet of paper.

2. MAKE A LIST OF WORDS THAT EXPRESS YOUR IDEA

You'll need to look further than the hot ideas from your object writing. Get out a thesaurus, one set up according to Roget's original plan according to the flow of ideas — a setup perfect for brainstorming. Dictionary-style versions (set up alphabetically) are useful only for finding synonyms and antonyms. They make brainstorming a cumbersome exercise in cross-referencing.

Your thesaurus is better than a good booking agent. It can churn up images and ideas you wouldn't ever get to by yourself, stimulating your diver to greater and greater depths until a wealth of choices litter the beaches.

Let's adopt the working title “Risky Business” and continue brainstorming the idea of homelessness. In the index (the last half of your thesaurus), locate a word the expresses the general idea, for example, risk. From the list below it, select the word most related to the lyric idea. My thesaurus lists these options for risk: gambling 618n; possibility 469n; danger 661n; speculate 791vb. The first notation should be read as follows: “You will find the word risk in the noun group of section 618 under the key word gambling.”

Key words are always in italics. They set a general meaning for the section, like a key signature sets the tone center in a piece of music.

Probably the closest meaning for our purposes with “Risky Business” is danger 661n. Look in the text (front half) of the thesaurus for section 661 (or whatever number your thesaurus lists; numbers will appear at the tops of the pages). If you peruse the general area around danger for a minute, you will find several pages of related material.

Here are the surrounding section headings in my thesaurus:

|

Ill health, disease |

Insalubrity |

Deterioration |

|

Relapse |

Bane |

Danger |

|

Pitfall |

Danger signal |

Escape |

|

Salubrity (well-being) |

Improvement |

Restoration |

|

Remedy |

Safety |

Refuge. Safeguard |

|

Warning |

Preservation |

Deliverance |

This related material runs for sixteen pages in double-column entries. Risk is totally surrounded by its relatives, so if you look around the neighborhood, you'll find a plethora of possibilities. Start building your list.

Look at these first few entries under danger: N. danger, peril; … shadow of death, jaws of d., dragon's mouth, dangerous situation, unhealthy s., desperate s., forlorn hope 700n. predicament; emergency 137n. crisis; insecurity, jeopardy, risk, hazard, ticklishness…

Look actively. If you take each entry for a quick dive through your sense memories, you should have a host of new ideas within minutes. (Frequent object writing pays big dividends here. The more familiar you are with the process, the quicker these quick dives get. If you are slow at first, don't give up — you'll get faster. Just vow to do more object writing.) Jot down the best words on your list and keep at it until you're into serious overload.

Now the fun begins. Start saying no to words in your list until you've trimmed it to about ten or twelve words with different vowel sounds in their stressed syllables. Put these survivors in the middle of a blank sheet of paper, number them, and enclose them in a box for easy reference later on. Keep these guidelines in mind:

-

If you are working with a title, be sure to put its key vowel sounds in the list.

-

Most of your words should end in a stressed syllable, since they work best in rhyming position.

-

Put any interesting words that duplicate a vowel sound in parentheses.

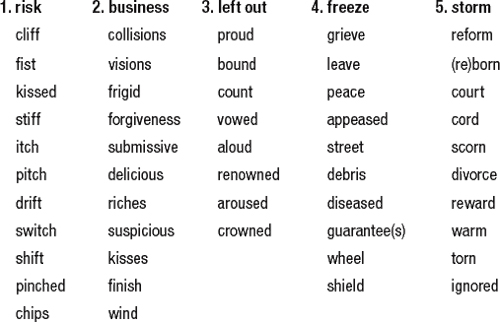

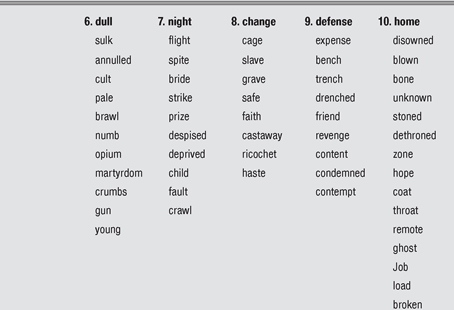

Your goal is to create a list of words to look up in your rhyming dictionary. Here's what I got banging around in the thesaurus, looking through the lens of homelessness:

-

risk

-

business

-

left out

-

freeze (wheel, shield)

-

storm

-

dull (numb)

-

night (child)

-

change

-

defense

-

home (hope, broken, coat)

This is not a final list. Don't be afraid to switch, add, or take out words as the process continues.

3. LOOK UP EACH WORD IN YOUR RHYMING DICTIONARY

Be sure to extend your search to imperfect rhyme types, and to select only words that connect with your ideas. Above all, don't bother with cliché rhymes or other typical rhymes. First, a quick survey of rhyme types.

Perfect Rhyme

Don't let yourself be seduced by the word “perfect.” It doesn't mean “better,” it only means:

-

The syllables' vowel sounds are the same.

-

The consonant sounds after the vowels (if any) are the same.

-

The sounds before the vowels are different.

Remember, lyrics are sung, not read or spoken. When you sing, you exaggerate vowels. And since rhyme is a vowel connection, lyricists can make sonic connections in ways other than perfect rhyme.

Family Rhyme

-

The syllables' vowel sounds are the same.

-

The consonant sounds after the vowels belong to the same phonetic families.

-

The sounds before the vowels are different.

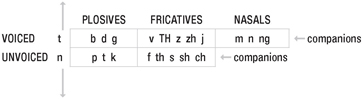

Here's a chart of the three important consonant families:

Each of the three boxes — plosives, fricatives, and nasals — form a phonetic family. When a word ends in a consonant in one of the boxes, you can use the other members of the family to find perfect rhyme substitutes.

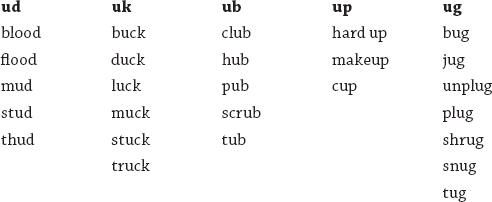

Rub/up/thud/putt/bug/stuck are members of the same family — plosives — so they are family rhymes.

Love/buzz/judge/fluff/fuss/hush/touch are members of the fricative family, so they also are family rhymes.

Strum/run/sung rhyme as members of the nasal family.

Say you want to rhyme this line:

I'm stuck in a rut

First, look up perfect rhymes for rut: cut, glut, gut, hut, shut.

The trick to saying something you mean is to expand your alternatives. Look at the table of family rhymes below and introduce yourself to t's relatives:

That's much better. Now we find that we have a lot of interesting stuff to say no to.

What if you want to rhyme this:

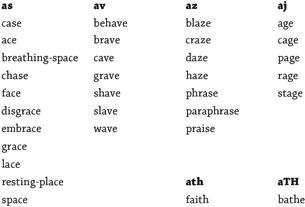

There's nowhere I can feel safe

First, look up perfect rhymes for safe in your rhyming dictionary. All we get is waif. Not much.

Now look for family rhymes under f's family, the fricatives. We add these possibilities:

Finally, nasals. The word “nasals” means what you think it means: All the sound comes out of your nose. Rhyme this line:

My head is pounding like a drum

Look up perfect rhymes for drum: hum, pendulum, numb, slum, strum.

Go to the table of family rhymes and look at m's relatives:

|

un |

ung |

|

fun |

hung |

|

gun |

flung |

|

overrun |

wrung |

|

won |

sung |

|

jettison |

|

|

skeleton |

Finding family rhyme isn't difficult, so there's no reason to tie yourself in knots using only perfect rhyme. Family rhyme sounds so close that when sung, the ear won't know the difference.

Additive Rhyme

-

The syllables' vowel sounds are the same.

-

One of the syllables add extra consonants after the vowel.

-

The sounds before the vowels are different.

When the syllable you want to rhyme ends in a vowel (e.g., play, free, fly), the only way to generate alternatives is to add consonants after the vowel. The guideline is simple: The less sound you add, the closer you stay to perfect rhyme.

Look again at the table of family rhymes. Voiced plosives — b, d, g — put out the least sound. Use them first, rhyming, for example, ricochet with paid; then the unvoiced plosives, rhyming free with treat. Next, voiced fricatives, rhyming fly and alive. Then on to unvoiced fricatives, followed by the most noticeable consonants (aside from l and r), the nasals. You'd end up with a list moving from closest to perfect rhyme to furthest away from perfect rhyme. For example, for free, we find: speed, cheap, sweet, grieve, belief, dream, clean, deal.

You can also add consonants even if there are already consonants after the vowel, for example: street/sweets, alive/drives, dream/screamed, trick/risk.

You can even combine this technique with family rhymes, such as dream/cleaned, club/floods/shove/stuff ed. This gives you even more options, making it easier to say what you mean.

Subtractive Rhyme

-

The syllables' vowel sounds are the same.

-

One of the syllables adds an extra consonant after the vowel.

-

The sounds before the vowels are different.

Subtractive rhyme is basically the same as additive rhyme. The difference is practical. If you start with fast, class is subtractive. If you start with class, fast is additive.

Help me please, I'm sinking fast

Girl, you're in a different class

For fast, you could also try: glass, flat, mashed (family), laughed (family), crash (fam. subt.).

The possibilities grow.

Assonance Rhyme

-

The syllables' vowel sounds are the same.

-

The consonant sounds after the vowels are unrelated.

-

The sounds before the vowels are different.

Assonance rhyme is the furthest you can get from perfect rhyme without changing vowel sounds. Consonants after the vowels have nothing in common. Try rhyming:

I hope you're satisfied

For satisfied, we come up with: life, trial, crime, sign, rise, survive, surprise.

Use these rhyming techniques. You'll have much more leeway saying what you mean, and your rhymes will be fresh and useful. Again, look actively at each word. Use them to dive through your senses, as though you were object writing.

You'll find more on these rhyme types, including helpful exercises, in my book Songwriting: Essential Guide to Rhyming.

Rhymes and Chords

You can think about rhyme in the same way you think about chords. Go to the piano and play three chords: an F chord with an F as the bass note in the left hand, then G7 with G as the bass note, then, finally, C. Play the C chord with the notes C, E, and G in the right hand, and a C as a bass note in the left hand. Sing a C, too. It really feels like you've arrived home, doesn't it?

Next, do the same thing again with your right hand, singing a C when you get to the C chord, but this time, put a G in the left hand. It still feels like you're home, though not quite as solidly as when you played C in the bass. Still, it's difficult to notice the difference.

Do it all again, this time playing the third in the bass, an E. It still feels like a version of home, but less stable. It seems to have some discomfort at home — a very expressive chord.

Do it again, keeping the E in the bass, but this time take the C out of the chord in your right hand. Sing the C. This feels even less comfortable.

Last time, add a B to the right hand, still leaving the C out. Now, you're actually playing an E minor chord, the three minor in the key of C, still singing the C. Now we have only a suggestion of home, rather than sitting down to the supper table.

All of these voicings are useful, and all of these voicings are tonic (home) functions. Some land solidly and bring motion to a complete halt. Others express a desire to keep moving somewhere else — a kind of wanderlust. Each has its own identity and emotion.

Rhymes work the same way. Some are stronger than others and express a desire to stay put; they are stable. Others may have a foot at home, but their minds are looking for the next place to go. They feel less stable.

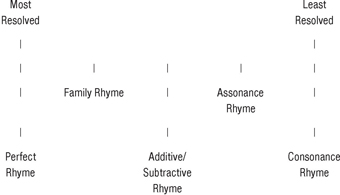

Here are the rhyme types, listed like the chords you played, in a scale from most stable to least stable:

RHYME TYPES: SCALE OF RESOLUTION STRENGTHS

Look at the simple example below — a stable, four-stress couplet. With perfect rhyme, it feels very solid and resolved:

A lovely day to have some fun

Hit the beach, get some sun

As we move through the rhyme types, things feel less and less stable, even though the structure remains the same:

Family rhyme:

A lovely day to have some fun

Hit the beach, bring the rum (a lot like C with G in the bass)

Additive rhyme:

A lovely day to have some fun

Hit the beach, get some lunch (a lot like C with E in the bass)

Subtractive rhyme:

Hit the beach and get some lunch

A lovely day, have some fun (a lot like C with E in the bass)

Assonance rhyme:

A lovely day to have some fun

Hit the beach, fall in love (a lot like C with E in the bass, no C in the right hand)

Consonance rhyme:

A lovely day to have some fun

Hit the beach, bring it on (a lot like the E minor in the key of C)

Expanding your rhyming possibilities accomplishes three things:

-

It multiplies the possibility of saying what you mean (and still rhyming) exponentially.

-

It guarantees the rhymes will not be predictable or cliché.

-

Most important, it allows you to control, like chords do, how stable or unstable the rhyme feels, allowing you to support or even create emotion with your rhymes.

Together, these offer a pretty good argument against the proponents of “perfect rhyme only.”

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know you

Ah yes, understand. Telegraphed and locked down. Mostly, I find it disappointing when I know what's coming. When it's already telegraphed and waltzing in your brain, why say it? If you instead said something different, you'd have both messages at the same time:

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know you'll take a stand (understand, the expected cliché, is still present.)

I like the perfect rhyme here. The full resolution seems to support the idea. Now, how about:

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know you'd like to dance

I love the surprise here. It also uses the telegraphing of understand as a second message. It's not a cliché rhyme. Pretty close, though, with n in common but d against c. That little bit of difference introduces something that perfect rhyme can't: a tinge of longing created by the difference at the end. The lack of perfect rhyme creates the same kind of instability as, say, the C major triad with a G in the bass. Almost, but not fully resolved. Just as a chord can create an emotional response, so can a less-perfect rhyme:

WORKSHEET: RISKY BUSINESS

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know you're making plans

The same tinge of instability.

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know you want to laugh

What do you think the chances of hooking up are now? They seem about as remote as the assonance rhyme. Yup, the rhyme type really can affect and color the idea.

It's still a “tonic” function, but now it seems more like a C major triad with an E in the bass.

Finally:

Baby baby take my hand

Let me know I'm on your mind

Now there's curiosity and uncertainty, expressed completely and only by the consonance rhyme. Pretty neat, huh?

Brainstorming

Brainstorming with a rhyming dictionary prepares you to write a lyric. At the same time you are brainstorming your ideas, you are also finding sounds you can use later. With solid rhyming techniques that include family rhymes, additive and subtractive rhymes, assonance and even consonance rhymes (especially for l and r), using a rhyming dictionary can be as relaxed and easy as brainstorming with a friend, except it's more efficient than a friend, and it won't whine for a piece of the song if you get a hit.

A worksheet externalizes the inward process of lyric writing. It slows your writing process down so you can get to know it better, like slowing down when you play a new scale to help get it under your fingers. The more you do it, the faster and more efficient you'll get.

The sample worksheet on pages 44–45 includes both perfect and imperfect rhymes. Reading this worksheet should be stimulating. But doing your own worksheet will set you on fire. Decide now that you will do a complete worksheet for each of your next ten lyrics, then stick to it. The first one will be slow and painful, but full of new and interesting options. By the third one, ideas will be coming fast and furious. You will have too much to say, too many choices, and too many rhymes. Though getting to this point takes work, it will be well worth the effort. Think of all the times you'll get to say no. No more clichés. No more forced rhymes. No more helpless gratitude that some idea, any idea at all, came along. No more six-hour gigs in Bangor for twenty bucks. Trust me.