CHAPTER FOURTEEN

METER:

SOMETHING IN COMMON

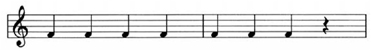

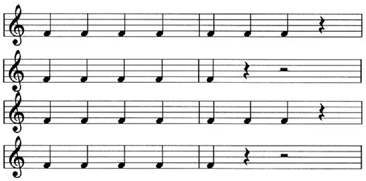

The sea captain of Western popular music is the eight-bar musical section, subdivided into two- and four-bar units. Expressed in quarter notes, old salty looks like this:

The eight-bar system is really one piece. Each of the subdivisions is a landmark along the voyage, giving directions and charting relationships. The end of bar two rests:

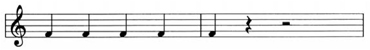

Then we tack into bars three and four:

![]()

What a different trip this section is (probably headed into the wind). Though we're at the end of four bars, we certainly feel unbalanced, and must continue:

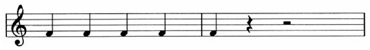

That's better; now we're in familiar territory. Not only that, but we know exactly what to expect next. Because of the match between bars one and two and bars five and six, we expect bars seven and eight to match bars three and four. When they do, we have arrived at the end of the trip. We feel stable:

Of course, this has been a very simple trip, but you'd be surprised how basic it is to Western music, from Bach to Berry. Go back and take another look at the complete thing, and, while you're at it, mark the strong and weak notes in each two-bar group:

|

DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM |

4 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM |

3 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM |

4 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM |

3 stresses |

The continuous voyage is organized according to a very simple principle: longer / shorter / longer / shorter.

You can't stop until you get to port. Now look at this simple nursery rhyme:

|

Máry hád a líttle lámb |

4 stresses |

|

Its fléece was whíte as snów |

3 stresses |

|

And éverywhére that Máry wént |

4 stresses |

|

The lámb was súre to gó |

3 stresses |

Yup, it has something in common with the voyage we just took:

|

DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM |

4 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM |

3 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM |

4 stresses |

|

DUM da DUM da DUM |

3 stresses |

Like the eight-bar unit, this meter is the staple of songwriters, from the early troubadours to Tom Waits. It is even called common meter, partly because of its pervasiveness (the basis of nursery rhymes — e.g., “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary,” “Old Mother Hubbard”), and partly because of its relationship to musical form. Imagine our old seafarer singing:

|

O Western wind, when wilt thou blow |

4 stresses |

|

The small rain down can rain? |

3 stresses |

|

Christ, that my love were in my arms |

4 stresses |

|

And I in my bed again |

3 stresses |

Since common meter is based on strong stresses, it doesn't really matter where the unstressed syllables fall. Like this:

|

If Máry hád a líttle lámb |

4 stresses |

|

Whose fléece was whíte as snów |

3 stresses |

|

Then éverywhére Máry wént |

4 stresses |

|

The lámb would be súre to gó |

3 stresses |

Or even this:

|

It was Máry who hád the líttlest lámb |

4 stresses |

|

With fléece just as whíte as the snów |

3 stresses |

|

O and éverywhére that Máry might chánce |

4 stresses |

|

The lámb would most súrely gó |

3 stresses |

Sometimes, common meter omits a strong stress. The most usual variation shortens the four-stress lines to three stresses, and adds an unstressed syllable at the end:

|

Sátan rídes the fréeway |

3+ stresses |

|

Pláying róck and róll |

3 stresses |

|

Gíve him lnáes of léeway |

3+ stresses |

|

He lóngs to dríve your sóul |

3 stresses |

It still works the same way: longer / shorter / longer / shorter.

The important point is that the first and second phrases don't match; three-plus stresses is still longer than three stresses.

Sometimes a strong stress isn't really that strong, as seen in this selection from Emily Dickinson:

|

I heard a fly buzz when I died |

4 stresses (2 adjacent) |

|

The stillness in the room |

2 stresses (in is pretty wimpy) |

|

Was like the stillness in the air |

4 stresses (2 of which are pretty wimpy) |

|

Between the heaves of storm |

3 stresses |

Common meter is nothing if not flexible. Sometimes the four-stress lines divide into two phrases. Sometimes the four-stress and three-stress lines add up to one complete phrase. Here are both events in one verse (written in triple meter) from Gordon Lightfoot's “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”:

|

They might 'a split up or they might 'a capsized |

2 phrases, each |

|

2 stresses |

|

|

They might have broke deep and took water And all that remains is the faces and names Of the wives and the sons and the daughters |

2 lines equal one phrase of 7 stresses |

Common meter is a great starting point for creating a lyric, and for assuring a musical match. But remember, I said starting point. Writing in common meter is not a goal, it is a tool. Since common meter creates expectations, you can learn to create nice little surprises. Watch Paul Simon work his magic in these two lovely unbalanced bridges.

First, from “Still Crazy After All These Years”:

|

Foúr in the mórning, craáped out, yaẃ ning |

4 stresses |

|

Lonǵing my lífe awaý |

3 stresses |

|

I'ĺl never worŕy, wáy should Ì |

4 stresses |

|

It's aĺl gonna fáde |

2 stresses |

|

(unbalanced) |

The short ending leaves us hanging, supporting the emotion of the bridge. (What? Structure can be used to support emotion? Yup. Structure can be used to support emotion.)

Next, from “Train in the Distance”:

|

Tẃo disappoińted beliévers |

3+ stresses |

|

Twó people pláying the game |

3 stresses (people set on weak beats) |

|

Negótiátions and lo⊨esongs |

3+ stresses (songs is weak in lovesongs) |

|

Are oöten mistáken for ońe and the saǂe |

4 stresses |

The last line unbalances the section and turns spotlights on the idea. A neat and effective ploy: If you want people to notice something, put it in spotlights. Ergo, put your important ideas in spotlights. Corollary: Don't turn on spotlights just to be cute.

Learn to cram your ideas into alternating four-stress and three-stress phrases. If they resist, let them, and see whether the results create any nifty little surprises, especially if the surprises help the meaning. The exercise will do you good; it will help you chart your course more clearly, and in stages that are foreseeable and easy to accomplish. If you need to take a detour, you will know where you are when you leave, and it will help you keep safely under control. A simple detour:

|

You've never felt what lonely is |

4 stresses |

|

Till you've flown the night alone |

3 stresses |

|

And the wind has blown you almost to despair |

5 stresses |

|

The sky runs black as midnight |

3+ stresses |

|

And the strip is hard to see |

3 stresses |

|

Heading into Charlotte on a prayer |

5 stresses |

Organizing your ideas into common meter may take a little work, but probably not that much, since, with rhymes like “Old King Cole” and “Little Miss Muffet,” it is ingrained from your earliest childhood. You can practice with any idea — a telemarketing call for example:

I had to call to say hello

I hope you're gonna buy

Times are tough and rent is due

And I've got songs to write

Or deciding whether to call for a date:

I wanna call, I wanna call

I know I'll sound too scared

My self-esteem is plunging fast

O do I do I dare?

EXERCISE 16

Try doing this with your grocery list. Try one in duples — da DUM da DUM — and one in triples — da da DUM da da DUM.

Learn to think in common meter. It will give you plenty in common with every Billboard chart in history, and plenty in common with the language of song from its earliest chartings. You will be sailing through it and its variations as long as you write lyrics. It's a strong map to work from; it will help you chart a manageable course to keep you from getting lost when those prosodic zigs and zags take you into lovely and unexpected waters.