CHAPTER TWENTY

FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION

BUILDING THE PERFECT BEAST

OhMyGod, Artie, stop!” yells Herbie. Artie's '69 VW microbus wobbles over to the side of the road, next to a cream-and-baby-blue Maserati convertible parked in the lot. “Boy, I'd like to drive that beauty. Looks like it really flies.” “Whew,” whistles Artie, “look at it — low, wide wheelbase, scooped front, rear foil. Definitely built for speed.” A physicist or aeronautical engineer could give a more precise description, but Artie and Herbie have it nailed anyway. As much as they love Artie's microbus, they know it won't win any races, because it isn't built for speed. But that Maserati sure could. Intuitively, they apply the principle form follows function. If you asked them the right questions, they'd be able to describe the two ways this principle works:

-

When you look at an individual car, you can figure out what it's built to do (function) by its design (form). Conversely, when you build a car, you figure out its design by what you want it to do. If you want a racecar, build it heavy, wide, and lower in front than in back so the wind will press it to the track. If you want an economy car, build it light and shape it to cut wind resistance. You already know this as the principle of prosody.

-

When you look at two cars, you see whether they're different or the same. When they're the same design, they should have the same function. When they have different designs, they should have diff erent functions. This is the principle of contrast.

It doesn't matter whether we're talking about cars, rhyme schemes, architecture, or lyrics.

As a writer, you'll usually look from a car designer's perspective — from function to form. You know what you want to say, so you have to design form to support your ideas.

As we've seen, your tools for designing your lyric's shapes are phrase lengths, rhythms, and rhyme schemes. For example, say there's a place in your verse where emotion gets pretty active or intense. You might try putting rhymes (both phrase-end and internal rhyme) close together, and try using short phrases. Like this:

|

You can't play Ping-Pong with my heart |

a |

|

You dominate the table |

b |

|

My nerves are shot, you've won the set |

c |

|

Your curves have got me in a sweat |

c |

|

My vision's blurred, can't see the net |

c |

|

I'm feeling most unstable |

b |

Built for speed. The consecutive rhymes, “set/sweat/net,” slam the ideas home. The internal rhymes, “nerves/curves/blurred” and “shot/ got,” put us in overdrive. The acceleration creates prosody, the mutual support of structure and meaning — form follows function.

You can think of rhyme as a car's accelerator: The closer the pedal is to the floor, the faster the car moves. The closer the rhymes are to each other, the faster the structure moves. The farther away the pedal is from the floor, the slower the car moves.

Let's see what the ride would feel like if we toned down the rhyme action in the previous example:

|

You can't play Ping-Pong with my heart |

a |

|

You dominate the table |

b |

|

My nerves are shot, I've come apart |

a |

|

You wink and smile, still feeling playful |

b |

|

Weak and numb, I miss the mark |

a |

|

Feeling most unstable |

b |

Out pops the rear parachute. Prosody evaporates, or at least diminishes, when the rhymes are spread out into a regular pattern. But the short phrases in lines three, four, and five still press on the accelerator. If we lengthen some of the shorter phrases, we let off the gas even more:

|

You can't play Ping-Pong with my heart |

a |

|

You dominate the table |

b |

|

My nerves are shot, I've really come apart |

a |

|

You wink and smile, still feeling pretty playful |

b |

|

Weak and numb, I really miss the mark |

a |

|

Feeling most unstable |

b |

Look at what happens if we ease off on the rhymes, too, pushing them further apart:

|

You can't play Ping-Pong with my heart |

x |

|

You dominate the table |

b |

|

My nerves are shot, at last you've won the point |

x |

|

Your slams have put me in an awful sweat |

x |

|

My vision's weak, can't even see the ball |

x |

|

I'm feeling most unstable |

b |

Now the structure acts more like a slow-moving '68 VW microbus, while the meaning still dreams of checkered flags on the Grand Prix Circuit. Bad combination.

EXERCISE 44

We might as well destroy prosody completely while we're at it. This time, you do it. Rewrite the example below so lines three and five contain one long phrase each, instead of two shorter ones. Be careful not to rhyme.

|

You can't play Ping-Pong with my heart |

x |

|

You dominate the table |

b |

|

… |

x |

|

Your slams have put me in an awful sweat |

x |

|

… |

x |

|

I'm feeling most unstable |

b |

Compare your result to the original and you will see what an important role structure can play in support of meaning. If you're careful how you build your form, you can make it work for you. Tend to the prosody of form and function, and your structure will become a powerful and expressive ally rather than an obstacle standing between you and what you really meant to say.

THE PRINCIPLE OF CONTRAST

Herbie and Artie know the difference between their microbus and the cream-and-baby-blue Maserati. No big mystery — they're built different. This is another way to look at “form follows function.” Simple logic: Things that look the same should do the same thing. Things that look diff erent should do diff erent things. A microbus is not a Maserati.

Verses in a song should all have the same function — they develop the plot, characters, or situations of the song. That's why they're all called verses. Because the verses all have the same function, they should all have the same form. Easy, huh?

Or this: When you move from a verse to another function — for example, to a chorus function (commentary, summary) — the form should change: the rhyme scheme, phrase lengths, number of phrases, or rhythms of phrases. Maybe all four.

“Form follows function” is the real rationale behind what often look like silly rules:

-

All verses should have the same rhyme scheme!

-

Change the rhyme scheme when you get to the chorus.

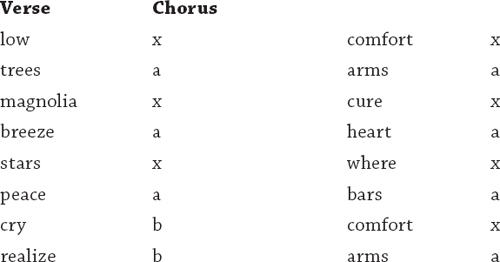

Look at this verse and its chorus:

Southern Comfort

Verse 1

Spanish moss hanging low

Swaying from the trees

Honeysuckle, sweet magnolia

Riding on the breeze

Southern evenings, Southern stars

Used to bring me peace

But now they only make me cry

They only make me realize

Chorus

There's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

You're the only cure

For this aching in my heart

I've searched everywhere

Tried the bedrooms, tried the bars

But there's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

Each section contains, roughly, the same number of phrases. No contrast there.

The verse rhymes its alternate lines, except at the end, where it accelerates with a couplet. The chorus rhymes every other line, too, without the couplet acceleration at the end:

Still not much contrast between the sections. The verse contains two complete sections of common meter rhythm. The only variation is the extra stressed syllable in the last line:

|

Stresses |

|

|

Spánish móss hánging lów |

4 |

|

Swáying fróm the treés |

3 |

|

Hóneysúckle, sweét magnólia |

4 |

|

Ríding ón the breéze |

3 |

|

Soúthern évenings, soúthern stárs |

4 |

|

úsed to bríng me peáce |

3 |

|

But nów they ónly máke me cry |

4 |

|

They ónly máke me réalizé |

4 |

That's a lot of common meter, but there's more. Look at the chorus:

|

Stresses |

|

|

There's nó Sóuthern Cómfort |

3+ |

|

Unléss you're ín my árms |

3 |

|

Yoú're the ónly cúre |

3 |

|

For this áching ín my heárt |

3 |

|

I've seárched éverywhére |

3 |

|

Triéd the bédrooms, triéd the bárs |

4 |

|

But there's nó Sóuthern Cómfort |

3+ |

|

Unléss you're ín my árms |

3 |

Although most of the phrases have three stresses, the section still leans toward common meter:

-

The balancing phrases are three stresses, the signature length of common meter.

-

The opening phrase is longer than three stresses, three plus — a normal variation of common meter's four-stress line. When you want two sections to contrast, the opening phrase of the new section must make a difference immediately. If you don't make a difference there, don't bother.

-

The two three-stress phrases with extra weak syllables are in the same positions as four-stress phrases in common meter, leaving only two contrasting phrases in the entire chorus. And they're the same length as half the lines in the verse.

Essentially, by the time we finish the chorus, we have been through four common meter systems. That's a lot. Imagine the boredom by the time you finish four more:

Verse 2

I've tried my best to ease the hurt

Leave the pain behind

But evenings sitting on the porch

You're always on my mind

Southern Comfort after dark

Helps me face the night

But there's nothing to look forward to

'Cept looking back to loving you

Chorus

There's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

You're the only cure

For this aching in my heart

I've searched everywhere

Tried the bedrooms, tried the bars

But there's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

Ho-hum structure. If the lyric's meaning were more interesting, there might be some hope, but it's not that interesting. Even if the meaning shone in eleven shades of microbus DayGlo, the structure still should help the meaning, not hurt it.

The bridge finally delivers a contrast:

Bar to bar

Face to face

Someone new takes your place

No one's ever new

I always turn them into you

But by the time we get to the bridge, it's too late; everyone has wandered off for a hot dog. Then there are two more lumps of common meter for the tombstone:

Chorus

There's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

You're the only cure

For this aching in my heart

I've searched everywhere

Tried the bedrooms, tried the bars

But there's no Southern Comfort

Unless you're in my arms

EXERCISE 45

with the chorus. You might look at Jim Rushing's “Slow Healing Heart” or Janis Ian's “Some People's Lives” for how to handle eight-line structures. Alternately, you might try unbalancing the structure by shortening it. Try it before you read further.

The rewrite below balances six lines against two, rather than dividing the verse into two four-line sections of common meter:

|

Rhyme |

Stresses |

|

|

Spánish móss hánging lów |

x |

4 |

|

Bówing fróm the trees |

a |

3 |

|

Hóneysúckle ríding ón the breéze |

a |

5 |

|

Sóuthern évenings, sóuthern stars |

x |

4 |

|

Swéet magnólia níghts |

x |

3 |

|

Uséd to bring me hármony and péace |

a |

5 |

|

Látely théy just máke me cry |

b |

4 |

|

They ónly máke me réalize |

b |

4 |

Chorus

There's no Southern comfort

Unless you're in my arms

You're the only cure

For this aching in my heart

I've searched everywhere

Tried the bedrooms, tried the bars

But there's no Southern comfort

Unless you're in my arms

Now the verse and chorus look different. Even Artie would notice. Though this lyric could still use major rewriting, at least its structure isn't stuck in the mud.

Prosody and Contrast

Of course, contrast between sections can also add prosody:

|

Verse |

|

|

If I went into analysis |

a |

|

And took myself apart |

b |

|

And laid me out for both of us to see |

c |

|

You'd go into paralysis |

a |

|

Right there in my arms |

b |

|

Finding out you're not a bit like me |

c |

|

Chorus |

|

|

Ready or not |

d |

|

We've got what we've got |

d |

|

Let's give it a shot |

d |

|

Ready or not |

d |

The chorus really zips along by changing to short phrases and consecutive rhymes. The speed is really a result of contrast; it seems so fast only because the verse has been so leisurely. Paul Simon's “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” and Beth Nielsen Chapman's “Years” both work on this same principle. Here's the first verse and chorus from “Years”:

|

Stresses (with musical setting) |

|

|

I went home for Christmas to the house that I grew up in |

6 |

|

Going back was something after all these years |

5 |

|

I drove down Monterey Street and I felt a little sadness |

6 |

|

When I turned left on Laurel and the house appeared |

5 |

|

And I snuck up to that rocking chair where the winter sunlight slanted on the screened-in porch |

9 |

|

And I looked out past the shade tree that my laughing daddy planted on the day that I was born |

9 |

|

Chorus |

|

|

And I let time go by so slow |

3 |

|

And I make every moment last |

3 |

|

And I thought about years |

2 |

|

How they take so long |

2 |

|

And they go so fast |

2 |

The verse lines are lingering and relaxed, just like the daughter. The chorus shows how fast years go by, accelerating the pace with shorter phrases. Not only is there contrast, but the contrast supports the meaning. Even within the chorus, the longer phrases slow time down, while shorter phrases step on the accelerator.

Chapman sets the first two lines into four bars of music. The last three also fit into four bars, but the last line, and they go so fast, is only one bar, supporting the lyric prosody perfectly. Nice stuff.

Become a designer; fit form to function. When you run with the LA fast-track set, step out with the Maserati. But when you want to join Artie and Herbie for the next Grateful Dead concert, go in style in the DayGlo microbus. Stop to consider what you need, and then build it. Have an effective, interesting structure ready for any occasion.