Chapter Eight

Plot the Dramatic Action

Plot is a series of scenes that are deliberately arranged by cause and effect to create dramatic action …

Dramatic action creates excitement and urges readers to keep turning pages in a book. Without the presence of drama, action can be considered passive or simply movement. Movement and momentum qualify as action, but movement wrought with conflict, tension, and suspense transforms into dramatic action—which, in turn, engages readers.

Dramatic Action vs. Passive Action

As carefully as you plot the overall dramatic action and sense of uncertainty in your stories, use the same level of scrutiny when tracking the type of action—dramatic versus passive—in each scene to create a sense of expectancy, anticipation, and longing in the reader.

When the protagonist is not in control of the action, this casts doubt about the character’s ability to succeed and renders the scene dramatic. If something or someone other than the protagonist is in control of the outcome, the action becomes dramatic and the consequences uncertain: “Will she or won’t she get what she wants?” This elevates the intensity of the drama (which is vital for your story), and the reader reads faster to learn the answer.

The term passive action may seem like an oxymoron. However, I use this label to identify any habitual action taken by the characters that results in no risk, obstacles, opponents, opposition, danger, uncertainty, or emotion. Passive action scenes fall below the Plot Planner line.

In small doses passive action has its benefits. It can show the character’s internal reaction to the external events, slow down the pace of the story, bring a bit of levity when the story becomes too gloomy, demonstrate the character’s demeanor when she isn’t under stress, reveal a deeper look into her inner life, give her a chance to create a new game plan, and give the reader a chance to breathe.

Some examples of passive action include:

- two characters window shopping and talking

- a character giving a presentation in his field of excellence

- two characters walking on a beach

- a character cooking breakfast and sitting down to eat it

Passive action scenes can also be called contemplative scenes, and they work best when they are short and placed between two dramatic action scenes. Too much passive action and your story stalls and you risk losing your reader’s interest.

Drama implies a power imbalance between the character and an antagonist, which creates dark emotions. The degree of imbalance determines the seriousness of the struggle. If, for example, your character is jogging on a city sidewalk, preoccupied by her shopping list, her upcoming meetings, and other mundane thoughts, this is considered action (or movement), but it is not dramatic action. Scenes with action of this type belong below the Plot Planner line. Dramatic action means that plenty of conflict, tension, suspense, uncertainty, and/or fear is present in the scene; in other words, drama. Think now of a scene in which your character is being chased by a gunman through grimy alleyways and is unable to think clearly because her fear is so great. This scene is filled with dramatic action and belongs above the Plot Planner line.

Keep these points in mind as you plan dramatic action within your scenes:

- If your protagonist is shown running in a scene, without the presence of drama, the action depicted is simply movement.

- Without the sense of the unknown, the action depicted is simply movement.

- Without great doubt about the character’s ability to obtain her goals (“Will she or won’t she succeed?”), the action depicted is simply movement.

- Without something or someone other than the protagonist in control of the action, the action depicted is simply movement.

Now that your scenes in the middle are in place, use your Plot Planner to help you determine the pacing of your dramatic action plot.

Test Scenes for Dramatic Action

Test Scenes for Dramatic Action

To test whether a scene has dramatic action, ask who controls the action, and likely the outcome, of the scene. Who is stronger and more powerful—the protagonist or the antagonist?

Take, for example, a character with a scene goal of enticing her crazy neighbor out of his house so she can see him for herself and thus win a bet. In this case, the protagonist’s fear overrides her curiosity, and she bolts before she can set her goal in motion. By surrendering her control and moving away from her goal, her fear works as an internal antagonist. Thus the scene belongs above the Plot Planner line.

The Pattern of Stories

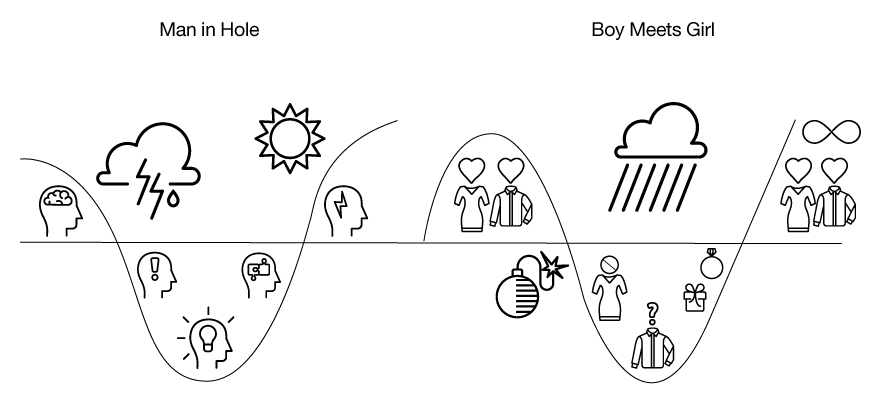

Guggenheim Fellow and award-winning novelist Kurt Vonnegut wrote his master’s thesis about the pattern of stories. Graphing the ups and downs of characters reveals the classification and arrangement of some of the more common and distinct story and plot types. He wrote: “The fundamental idea is that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper, and that the shape of a given society’s stories is at least as interesting as the shape of its pots or spearheads.” He believed in plotting on graph paper; I recommend banner paper. Following are two of his classic story shapes.

These images depict the crisis, or dark night, of the middle as falling into a hole or dark place. Though the Plot Planner instead traces a line that steadily moves higher, both visuals illustrate trouble. In Vonnegut’s graph, the main character’s circumstances of good fortune are plotted above ground while the line below reflects his ill fortune.

The Plot Planner line reflects the energy of the story rising in intensity scene by scene. That intensity is created by an antagonist’s good fortune causing the protagonist ill fortune. Both methods, though polar opposite reflections, are telling the same story—someone wants something, is interfered with, overcomes the opposition, and ends up better off than where they started.

Plot your story ideas on a Plot Planner with the action itself in mind for now. For each scene, simply determine if your protagonist is struggling against something or someone who wields more power, experience, wisdom, knowledge, skills, abilities, or favor, or if she is relatively in control. If she begins the scene in control, sure of what she is doing and where she is going, and she ends the scene in trouble, consider that entire scene as an above-the-line scene.

You’ll find scenes that fall short, do not meet the criteria, plummet below the Plot Planner line or, in Vonnegut’s story shapes, sit at ground level. For help in creating and plotting more tension and conflict in your scenes, see chapter nine.

Generating More Dramatic Action

If your scenes currently lack dramatic action, there are a number of ways to inject them with more.

- Call in the antagonists:

- Friends, family, or co-workers can stir up conflict for the protagonist.

- A natural disaster could be the problem your protagonist must face.

- A physical disability could hinder the protagonist from reaching his goal.

- The rules of religion, government, and customs might interfere with the protagonist’s needs or desires.

- The protagonist’s car could break down on the way to an important event.

- The protagonist’s motorcycle could skid on a slippery road.

- The protagonist could battle fears, flaws, or prejudice—either personal or that of others.

- The protagonist could face a ticking clock.

- Know the climax to help determine which antagonists are needed for the story in anticipation of what’s coming.

- Use foreshadowing in the middle to introduce overarching tension, conflict, or suspense in the plot.

- Delve more deeply into the character’s emotional development by detailing her reactions to the opposition she meets.

- When you test your scenes for cause and effect, ask yourself: Because this happens, what happens next? Also explore ideas that flow seamlessly from the scenes that came before and then twist the action in a seemingly impossible direction, complicating the character’s circumstances and thwarting reader expectations. For instance, the character (and the reader) believes she has identified the murderer, but on her way to confront the bad guy, she discovers his corpse.

- Don’t reveal everything at once. Leave hints and spread out the need-to-know details. Milk the suspense of the unknown. Curiosity drives the reader deeper into the story to learn the answers to the whys and hows you present.

- Add a great subplot like a relationship that thematically complements the primary plot and adds interest and complexity.

- Crescendo scenes in the middle with action and drama at the crisis that tops all the other setbacks and complications.

Right after the intensity of the crisis, the energy of the story drops off for a bit to allow the protagonist to catch his or her breath.