Chapter 4

Step-by-Step, How Do I Write Useful and Legally Defensible Reports?

In the prior chapters, we have made a case, hopefully a convincing one, for showing rather than telling readers you have met legal mandates, making reports more useful for the consumers, and why we advocate for the use of a referral-based, question-driven format that integrates data and responds directly to consumers’ concerns. In this chapter, we will examine each section of our proposed referral-based report and discuss step-by-step how to write a report using this structure. Where needed, we will discuss how this differs from what you might see in traditional test-by-test or domain-driven reports. There are several examples of full reports in Appendix II. It may be helpful for you to review some of these prior to reading how to structure a referral-based, question-driven report.

As we proceed, we want to remind you of several strategies, introduced in Chapter 3, that are overarching and perhaps not directly connected to the format you use to write your reports. These include using simpler language and reducing jargon, reducing boilerplate or generic statements, and carefully considering the level of detail needed to communicate with your intended audience.

How Do I Clearly Communicate the Purpose of the Evaluation?

The Reason for Referral section of the report communicates the background and rationale for the evaluation. In other words, the reader should know from reading the Reason for Referral section what led to the request for an evaluation and what issues are of concern to those who made the request. Many reports we read provide brief statements that at best point you in a general direction. They are often generic and provide little information about this child and this evaluation.

Examples: Poorly Written Reason-for-Referral Statements

These brief statements provide a vague rationale for the evaluation but communicate almost nothing to the reader about the nature of the “concerns,” difficulties with academic progress,” or “services” in question. In the case of “A psychoeducational assessment was completed as part of a triennial review,” the author is stating a fact, which is evident in the report that follows, instead of providing an actual rationale. Of course, triennial reviews are required, but this is a generic legal requirement that communicates nothing about the particular child being reevaluated. Another example is a kind of fill-in-the-blanks template used for all evaluations in some school districts.

This is, of course, much longer than the prior examples but still contains very little information unique to a particular child. Although we appreciate the effort, other than describing the special education evaluation process, the only unique data are given in the listing of possible impairments. Unfortunately, the statement provides no information about the nature of these impairments and does little to help us understand why the school team is evaluating this specific child.

Another problem with the previous referral statements is that they refer to constructs (e.g., social/emotional behavior, attention, cognitive processes, and difficulties in academic progress) that do not have a commonly shared definition. Not only will readers such as parents and teachers not understand them, but also they do not have a commonly accepted meaning among psychologists. This, unfortunately, means that no one who reads these reports will have anything more than a vague idea of what concerns led to the referral.

The Reason for Referral section of the report should communicate the purpose of the evaluation and identify the areas of concern. In addition, to strengthen the legal defensibility of the evaluation, it should identify what disabilities are in question. In order to accomplish this purpose, the Reason for Referral section should: (a) concisely describe the background or recent history of the problem; (b) describe the concerns, behaviors, or symptoms that led to the referral; (c) identify what areas or domains are to be assessed; and (d) communicate what disabilities are suspected. As much as possible, this section of the report should describe the concerns in behavioral terms. It can also be useful to quote the persons making the referral, using their words to describe the problem (Ownby, 1997). This information should logically lead to explicit evaluation questions or hypotheses, which we will discuss in more detail in the next section.

One implication of this approach is that the Reason for Referral section will often be longer than is typical in most reports, perhaps two or three paragraphs. The good news is that many reports already contain this information and it is simply a matter of moving some of what is usually placed in a background section into the Reason for Referral section.

When written more comprehensively, the Reason for Referral section of the report helps document the legal mandate that we assess in all areas of suspected disability and areas of need. In addition, it focuses the evaluation and makes it more individualized for a particular child. As we discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, this often requires that we spend time up front gathering information and exploring the problem with parents and teachers. Ahead we offer some examples and a discussion about their structure.

Examples: Reasons for Referral

Each of the previous paragraphs communicates information about the recent history of the problem. For example, we know that Michael’s mother has been concerned about his academic progress and behavior for at least a year. We know that he was evaluated because of a suspected learning disability and ADHD and that the team did not find him eligible for special education services. We also know that Mrs. Smith is not content with that conclusion and wants the team to look into autism and emotional disturbance. Lastly, we know that the evaluation will cover a variety of domains, including academic skills, intellectual development, speech and language skills, psychomotor development, self-help, and social-emotional development.

We also know something about the symptoms or behaviors that have led to the referral for an evaluation. For Michael, we know that his mother believes he is not doing well in reading and that she and his teacher have been concerned about his being off-task, being out of his seat without permission, and “negative attention-seeking behavior.” For Kris, we know she is failing classes, misses classes frequently, and only completes about half of her work. We also know that her parents are concerned about depression and that she has attempted suicide five times. In each case, we also know what disabilities are suspected, moving us closer to meeting our legal obligation to assess in all areas of suspected disability and need.

Clearly, there are still questions. We do not really know why Michael’s mother has requested that the team focus on autism or emotional disturbance (other than that LD and ADHD were ruled out by the team first time around). There is obviously more to Kris’s story of five suicide attempts and how the suspected depression is manifesting other than poor attendance and work completion. Yet, when compared with the examples at the beginning of this section, these do a much better job of giving the reader the context and rationale for the referral.

We have found that there is a balance in writing the reasons for evaluation between too little and too much. Too little does not communicate sufficient information for the reader to understand what concerns led to the evaluation and what the hypotheses are about the cause of these problems (see the examples at the beginning of this section). Too much detail makes the Reason for Referral section cumbersome to read. The goal is to provide a brief, though specific, introduction to what follows, which will of course have much more detail.

The referral concerns lead to the referral, or evaluation questions. The evaluation questions should follow logically from the description of the concerns contained in the narrative of the Reason for Referral section. Together with the information in the Reason for Referral section, they provide a focus and guide for the evaluation.

How Do I Develop Well-Formed Evaluation Questions?

The information discussed in the Reason for Referral section should lead to explicit evaluation questions. In Batsche’s Referral-Based Consultative Assessment/Report Writing Model, after reviewing existing information about a student, the next step is to collaboratively develop the referral questions (1983). Like Batsche’s model, there should be a logical connection between the narrative of the Reason for Referral section and the evaluation questions that follow. Moreover, there should be logical connections between each aspect of the evaluation, including the reasons for the evaluation, the evaluation questions, the procedures chosen to conduct the evaluation, the results, and the recommendations that follow from the evaluation. This means that a reader should see the logical connection and flow between each stage of the evaluation.

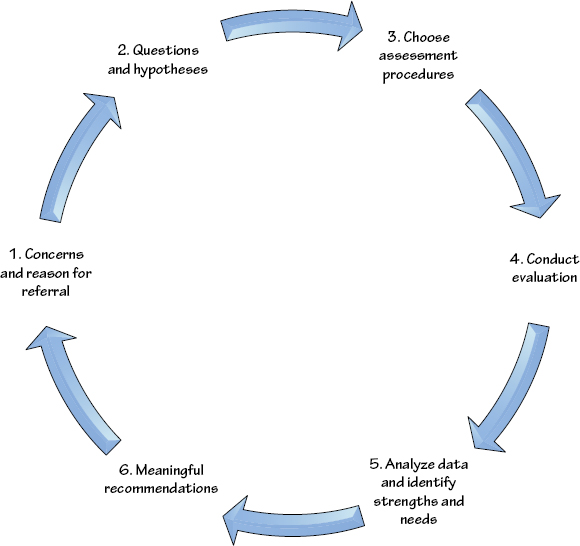

We represent this in Figure 4.1 as a continuous cycle that starts from a discussion of concerns and ends with the identification of strengths and needs. The cycle can of course start over, if there are new concerns or if the recommendations made do not adequately meet the identified needs. Like a good story plot, making our logic transparent goes a long way toward making reports more accessible and engaging to readers.

Figure 4.1 Evaluation Cycle

There is a legal framework for the types of questions that the evaluation must answer. Section 300.304 of IDEA notes the questions that an evaluation must answer:

In conducting the evaluation, the public agency must:

- Use a variety of assessment tools and strategies to gather relevant functional, developmental, and academic information about the child, including information provided by the parent that may assist in determining—

- Whether the child is a child with a disability under Sec. 300.8; and

- The content of the child’s IEP, including information related to enabling the child to be involved in and progress in the general education curriculum [emphasis added]. (IDEA, 2004)

We interpret (i) and (ii) as framing two types of questions for all evaluations: (1) disability or diagnostic questions, and (2) recommendations or “What do we need to do differently?” questions. Given that we are also responsible to assess in all areas of need related to the disability, and the psychoeducational evaluation is the foundation for the IEP, we add a third type of question, (3) current levels of functioning questions. In our reports we typically put the present-levels questions first, the diagnostic questions(s) second, and the “What do we need to do differently?” question last. In the following sections we discuss each of these in turn.

How Do I Write Present Levels of Functioning Questions?

Present-levels questions connect to the mandate to assess in all areas of need, whether or not they relate directly to the disabilities in question. They can, of course, vary depending on the child in question and the concerns raised by teachers or parents, but they often correspond to the areas listed on a typical assessment plan, for example, academic skills (reading, written language, and math), cognitive functioning, social emotional functioning, and so on. Samples of present-levels questions that correspond to the cases of Michael and Kris could include:

- What are Michael’s current levels of academic, cognitive, psychomotor, and social and emotional development?

- What are Kris’s current levels of academic, cognitive, and social and emotional development?

These examples of present-levels questions combine different areas of concern into one question. Although this may be appropriate in some situations, it can often be clearer to state each of these as a separate question. For example, Kris’s questions could be rewritten as three separate questions:

- What is Kris’s level of academic development?

- What is Kris’s level of cognitive development?

- What is Kris’s level of social and emotional development?

Returning to the section of IDEA that discusses evaluations, certain areas are specifically mentioned in the law:

(4) The child is assessed in all areas related to the suspected disability, including, if appropriate, health, vision, hearing, social and emotional status, general intelligence, academic performance, communicative status, and motor abilities [emphasis added]. (IDEA, 2004)

Given that school psychologists work in education, the issue of academic performance is always relevant in one way or another. For some children, the issue will be one of academic skill development, and for others, like Kris, who appear to have adequate skills, the more important issue will be one of classroom performance and the influence of motivation or the presence of behaviors that interfere with studying, completing work, or following classroom routines, such as inattention and impulsivity.

As we have discussed in Chapter 3, we also advocate for incorporating strengths into evaluations and reports. Returning to the present-level question above, they could be phrased to guide the evaluation to account for strengths and needs rather than just a level of functioning. For example, Kris’s present-level question, “What are Kris’s current levels of academic, cognitive, and social and emotional development?” would become “What are Kris’s academic, cognitive, and social and emotional strengths and needs?” If we separated them into three different questions, they would be:

- What are Kris’s academic strengths and needs?

- What are Kris’s cognitive strengths and needs?

- What are Kris’s social emotional strengths and needs?

Some school districts require that every child who is referred for an evaluation be assessed in certain areas. For example, every student is given a standardized test of intelligence or achievement, no matter the concerns raised by those who made the referral. This seems unnecessary, inefficient, and even intrusive. If there is good evidence from a child’s history that his academic skills are adequate (e.g., grades, work samples, district academic benchmarks, state testing, etc.), then it seems sufficient to use these data, usually gathered through reviews of records and interviews, to document the student’s present levels. Remember, we need to collect relevant data to help the IEP team write goals and create interventions. In this case, through our review of records and interviews we collected the relevant data needed and there is no reason to give a standardized achievement test. This allows the busy school psychologist to spend her or his limited time focusing on assessment concerns that are a higher priority instead of giving unwarranted standardized batteries.

District mandates that require the administration of a certain kind of standardized assessment seem to arise from a perspective that treats data from standardized tests as more legally defensible. We know of no evidence that suggests this is true. If called to testify regarding an evaluation, the standards by which that testimony would be judged would be similar to those used to judge expert witnesses and their testimony. If we examine how courts treat this issue, there is clearly room for judgments based on interpretation of the facts that draws upon professional knowledge and experience (Fed. R. Evid. 702 advisory committee’s note, 2000 amendments). Legally, psychologists are required to support their opinions, whether it involves use of a standardized test or professional judgment based on other kinds of assessment data.

How Do I Write Diagnostic or Disability Questions?

Simply put, legally all evaluations must determine whether a child has a disability and, if so, what kind. As we discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, it is good practice to identify what disabilities are in question up front, as part of the pre-assessment process. This is not only good practice but helpful in documenting your efforts to meet the legal mandate to assess in all areas of suspected disability. This is one of the problems with the poorly written referral examples on page 66. Although it identifies areas of potential impairment, it does not identify the suspected disabilities. We, as experienced professionals, could read between the lines and guess Other Health Impaired (because of possible ADHD implied by problems with attention) or Emotional Disturbance (implied by impairments of social/emotional functioning), but given the lack of other information, this is dangerously vague and not useful for those reading the report. We believe that it is much better to state explicitly the suspected disabilities in the questions that guide the evaluation.

The disability questions themselves are straightforward. There are 13 disabilities listed in IDEA (see Table 4.1). In most cases, you will quickly eliminate many of them because of your prior knowledge of the student’s concerns (e.g., deaf-blind, orthopedic impairment, etc.). Choosing the remaining suspected disabilities will depend on the quality of information you have at the beginning stages of the assessment process and your ability to clarify the referring parties’ concerns and formulate hypotheses.

Table 4.1 Disability Categories in IDEA 2004

| Autism Deaf-blindness Deafness Emotional disturbance Hearing impairment Intellectual disability Multiple disabilities |

Other health impairment Orthopedic impairment Specific learning disability Speech or language impairment Traumatic brain injury Visual impairment (including blindness) |

We often use the assessment plan itself as a guide. As we go through each area listed on the plan (e.g., academic skills, cognitive ability, motor skills, etc.), we ask the parent and teacher about their perceptions of the student’s strengths and weaknesses in each area. If something is not stated as an area of concern, we will ask questions that help us understand why this is not a concern. If something is stated as a concern (i.e., “Adrian just can’t seem to remember what I tell him to do”), we ask questions that help clarify what this looks like and what might be underlying this problem. For example, we would want to know if Adrian’s difficulty with remembering instructions was related to attention, motivation, memory, or some combination of these factors. During this process, we will sometimes ask direct questions such as “Do you think Adrian has a learning disability?” or “Has anyone ever mentioned autism to you in talking about Adrian’s difficulties?” This back-and-forth conversation inevitably narrows down our list of suspected disabilities and helps us identify what domains are of concern. Although not directly related to this topic, this early collaboration with parents and teachers also helps the IEP members feel like participants in the evaluation process, rather than uninvolved observers while we conduct our assessments.

Using Michael’s sample Reason for Referral statement, we can reasonably develop evaluation questions that focus on identifying a short list of suspected disabilities. For example, Does Michael have autism or an emotional disturbance, as defined by IDEA? In Michael’s case, the most important reason for these disabilities to be included is that his mother has requested that the evaluation focus on them. In other words, Michael’s mother suspects them, so they automatically go on to the list of concerns we discussed in Chapter 2. There is some evidence that supports these hypotheses, such as lack of friendships and odd behavior on the playground, but from a conservative legal perspective, Mrs. Smith’s concerns trump the school personnel’s opinion about the strength of this evidence.

Does Kris have an emotional disturbance as defined by federal and state regulations? This question seems more straightforward. Kris earned good grades before high school, which does not give strong support to a learning disability. The concerns focus on depression, suicide attempts, poor school attendance, and poor work completion. Given this, it seems logical that an emotional disturbance would be the strongest hypothesis for an educational disability.

How Do I Write Solution-Based, or “What Do We Do About This” Questions?

The last type of question is the “What do we do about this?” question. It is in our response to this question that we make the recommendations that flow from our identification of the child’s strengths and needs. If needed, this is also where we make recommendations about the content of a child’s individualized education program. We often phrase this as two questions. One question focuses on what might be necessary for the child to make adequate progress as judged by academic standards. The second asks if special education is necessary in order to accomplish this. Examples of these questions for both an initial evaluation and a reevaluation follow.

Examples: “What Do We Do About This?”—Initial Referral Questions

Examples: “What Do We Do About This?”—Triennial or Three-Year Reevaluation Questions

These types of questions put the issue of “What do you do about this?” and our recommendations front and center in our reports. Once evaluation questions are developed, the school psychologist determines what evaluation tools to use and what data to collect to answer these questions. It is beyond the scope of this book to delve into assessment practices and tools for each area of suspected disability; however, we hope you keep in mind the legal and best practice assessment points we have highlighted:

- The evaluation should be comprehensive.

- The evaluator should use a variety of assessment tools or approaches that gather functional and relevant data.

- The evaluation should be fair.

- The evaluator should be competent.

- The procedures used should be valid and reliable.

In the following sections, we discuss how to use evaluation questions as the structure for your reports. We also discuss how to write background information, assessment themes, and good recommendations.

The Background Information Provides Developmental and Educational Perspective to Your Report

The background information in a report has two important purposes. The first is to provide sufficient information about children to situate them in a developmental, social, and educational context. To return to our analogy of report as a story, it is important to know enough about the protagonist of a story in order to understand the implications of the plot. In the same way, it is important that we have enough basic information (e.g., gender, age, grade, family composition, etc.), in order to understand both the concerns and the results of the evaluation.

The second purpose of the background information is to identify social, health, or developmental factors that might play a role in explaining the concerns raised by consumers. Examples might include a previously unidentified hearing problem or a history of poor attendance and limited access to instruction. These factors can play a role in decision making by either their presence or their absence. The presence of symptoms early in development can play a direct role in diagnosing such disabilities as an intellectual disability, autism, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The absence of certain background variables can also play a role in deciding that a lack of academic progress is best explained by a lack of instruction or a health condition rather than a learning disability or that a child’s symptoms of hyperactivity are caused by ADHD rather than lack of sleep or medication taken for an illness. The background information can be structured in two ways. One is to give it the heading of Background Information as would be typical in most report structures. The second is to present it as a question, similar to the questions we have discussed. An example of how the Background section can be framed as a question is:

How does Anthony’s developmental, health, and educational history affect his academic achievement?

Either way, it is important to begin this section with an explanation of the source of the information we report. As with other aspects of the evaluation, this makes clear the sources of our information and any potential limitations of the data we have gathered.

Examples: Providing Sources of Background Information

Following this introduction, we must make important decisions about what to include or not include in this section. One of the common challenges we face is sorting through the large amount of background information gathered during an evaluation and determining what information is important to highlight. This decision has both ethical and practical implications.

First, it is important to understand the scope of our evaluation. This helps us answer the question, “Is this relevant?” We have advocated for clearly stating the reasons for the evaluation and for developing questions that will guide the evaluation. This helps us understand the scope or purpose of the evaluation before we start, but also helps us communicate that purpose to the readers. Communicating the purpose of the evaluation clearly is not only an important aspect of informed consent and developing a collaborative relationship with consumers, but it can also help us decide what is relevant to include in a report. If the information we have gathered does not assist us in answering the evaluation questions we have posed, it is probably not pertinent and should not be included.

Second, the first goal of most ethical codes is typically beneficence, or the duty to do no harm. Given this, in addition to asking if the information helps us tell the story of a child accurately or if it helps us answer one of the evaluation questions, it is important to ask also if the information will do harm or break confidentiality in unnecessary ways (Michaels, 2006).

There is, of course, a tension in answering these two questions. Revealing a mother’s drug use during pregnancy may be helpful in understanding a child’s symptoms of hyperactivity but may also embarrass or deepen a sense of guilt or shame she has about the experience. In the spirit of a collaborative relationship, we will often either ask if it is okay to put a sensitive piece of information in a report or, if we have strong feelings that it is necessary, will at least frontload the parent (or child) that the information will be included and what our rationale is.

There are many ways to sequence or structure the information in the Background section but we often start by situating the child in a family. With bilingual youth, this is also where we will discuss language usage.

Examples: Situating the Child in a Family

Note that both Peter and Kendra live in families where there has been a divorce. This is a good example of potentially sensitive information. Our decision in these cases is that this is important basic information for understanding these families and potential sources of social support or stress. We would be cautious beyond this basic information. For example, it is probably not worth mentioning that Peter’s mother had mentioned she was “disgusted” by her ex-husband’s “fooling around and wasting money” behavior. This information is likely not pertinent to the referral questions and has at least some potential for harm. We understand that there might be situations where the tension between separated parents or other family issues may play an important role in explaining a child’s problems. As we mentioned earlier, we think it is best practice to discuss this with the parent beforehand. We are also cautious about interpreting or putting our own spin on this kind of information and will often use the informants’ own words to describe the situation. For example, we might say, “Mrs. Lopez describes her relationship with Peter’s father as ‘difficult’ and says the separation has been ‘very difficult on both me and Peter.’”

We typically follow this section with information about the birth, early development, and health. This is the part of the Background section where we also describe the child’s current health status, including any medical concerns and treatment, as well as current vision and hearing. We encourage writers of reports to phrase information positively. In other words, rather than saying, “Mike did not have any problems at birth and his mother says he did not experience any developmental delays,” we prefer to say, “Mike and his mother were healthy at his birth. His mother reports that he met his early developmental milestones within typical time frames.” The goal here is not to gloss over negative experiences or challenges, but whenever possible, describe the presence of something rather than the absence of something. For example, someone is “healthy” rather than “does not have any health problems.” This is not only easier to understand for the average consumer but also avoids the off-putting use of unnecessarily negative language in our reports. Some examples of this section include the following.

Examples: Using Positive Language

After providing information about birth, early development, and health, we will also discuss any prior community-based evaluations and treatment. If the child was evaluated by a school district, we usually incorporate these data into the Education History section that follows.

Examples: Medical or Treatment History

Following the information about birth, early development, and health, we would typically discuss the child’s educational history. This can vary considerably depending on a child’s educational experiences. The following are examples of an initial referral with a complex history, an initial evaluation with a less complex history, and a special education reevaluation.

Examples: Educational History

Some authors include information about a child’s hobbies, friendships, relationships with parents, and so on in the Background section. For the most part, we have found that this information is better placed in the Evaluation Results section as part of our response to the evaluation questions. For many of the children we evaluate, their social and emotional functioning is a concern. Given this, information about these topics, even if it is historical, is usually important in answering an evaluation question regarding their emotional status and ability to get along well with peers and adults. In addition, in the next section we will further discuss how developing and answering specific evaluation questions pushes us to integrate different sources and kinds of data and look past the kinds of categories found in test-based and domain-based report structures.

Assessment Data from Multiple Sources Is Integrated into Themes

If you were writing a report using the approach we advocate, you would so far have: (a) a Reason for Referral section that explains the rationale and purpose of the evaluation; (b) a short list of evaluation questions; and (c) a Background section that provides the developmental, health, social, and educational context for the referral. What would typically follow this in a more traditional report would be an Evaluation Results section that would perhaps be divided into subheadings based on the instruments you used (a test-based format) or domains of functioning (a domain-based report). Instead, we recommend that you use the evaluation questions as the basic structure for your Evaluation Results section. As we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, we recommend you put the present-levels questions first, the disability question second, and the “What do we need to do differently?” question last.

Example: Referral-Based Report Structure

With this model, you first pose and then answer the questions. Questions 4a–e become the subheadings for your Evaluation Results section. In many reports, interpretation and integration of data is left to the Conclusion or Summary section. Our reports do not contain a summary or conclusion because the interpretation and integration of assessment data is ongoing and explicit in how we answer the evaluation questions. We agree with Batsche (1983) that integration of assessment data should occur throughout the report and believe this structure lends itself to the greatest integration of data.

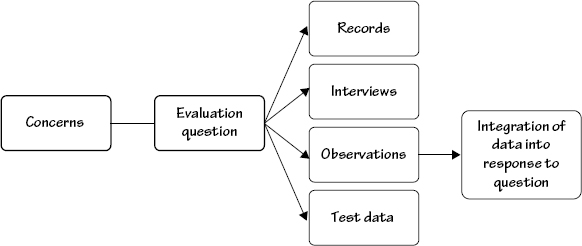

We want to be clear about the implications of this. For example, we do not have an “observations” section or an “interview” section but rather all information is integrated throughout the report. The response to an evaluation question may draw upon history, interview data, observations, or test results. Figure 4.2 represents how we conceptualize this.

Figure 4.2 Integration of Information in Response to Evaluation Question

This approach is challenging for us as authors because it forces us to think through all of the data we have gathered for the information that helps us answer each of the evaluation questions. This moves us in the direction of integrating different types of data to answer the question, a clear legal as well as best practice mandate. For example, in question 4a it would be common for us to discuss teacher reports, state testing, district benchmarks, and standardized academic test batteries. In the answer to the second question, 4b, we might include developmental information, teacher and parent reports, and the results of a standardized assessment of cognitive skills.

Within each section of the evaluation results, we will often use theme statements as another organizing tool. A theme statement is a concise (from one to three sentences) summary of the information that follows. One way to think about this is if we lifted the questions and themes statements from a report, we would essentially have an outline of our evaluation. Another way to understand the themes is that they are the answers to our evaluation questions. They are our major findings or conclusions, which, instead of being placed in a summary or conclusion, are integrated throughout the report as responses to the evaluation questions. In addition to being concise, theme statements should be written in straightforward language without reference to technical data. We typically highlight theme statements by using bold or italic type or placing them in text boxes in our reports. We will also usually place a statement at the beginning of the Evaluation Results section before our findings or responses to the evaluation questions, to explain the question-based format to the reader. An example of this is:

The assessment questions addressed within this report are listed as headings below. After each question, the answer is provided in italics. The information and data used to answer the questions are also provided in the narrative following each question. Specific scores on standardized assessments are included on the last page of the report.

We provide sample theme statements taken from our reports in what follows. Some are in response to present-levels questions and some in response to disability questions.

Examples: Sample Theme Statements

What follows each theme statement is a narrative that supports the theme by providing information integrated from various sources. This is a key point; rather than categorize information by domains or by the instrument used, it is organized so it responds to the evaluation questions posed. To return to our metaphor of report as story, the goal is to present a coherent plot that the reader can follow, using the questions as the basic structure. As to how much information is adequate to support a theme, we again suggest using Merrell’s Rule of Two and RIOT as guides (Leung, 1993; Levitt & Merrell, 2009). Two examples of what the combination of question, theme statement, and supporting data might look like follow. To see more examples, refer to Appendix II at the end of the book.

Examples: Pulling It All Together—Question, Theme (Answer), and Data

Note again the integration of different kinds of data in both examples. In a more traditional report, some of the information in Kris’s example (e.g., grades, credits earned, etc.) might have been placed in a Background section or the Academic Achievement section. Here the question is answered by a combination of current information from school records and historical information from a prior evaluation. In Drew’s example, information gathered through records review and a parent interview was combined to look at his history as a whole.

The number of themes is of course dependent on the question asked and the data gathered and there may be multiple themes throughout the answer of a question. A simple outline of what this might look like in a report would be:

- Evaluation results

- What are Kris’s academic strengths and needs?

- Theme 1

- Evaluation data

- Theme 1

- Evaluation data

- Theme 1

- What are Kris’s academic strengths and needs?

We have found this format to be especially helpful when talking to parents and teachers about the evaluation results. What we typically do is to start the conversation with a reminder of the concerns discussed in the early stages of the evaluation process and then move on to pose and answer each question in turn. The questions and theme statements provide a natural outline for discussing the results and the recommendations that follow.

To summarize, use theme statements as summary statements or subheadings in the narrative response to an evaluation question. The questions and theme statements are a way of structuring the Evaluation Results section so that it focuses explicitly on the questions raised by consumers. They are concise, written in straightforward, nontechnical language, and typically draw upon data across assessment methods or sources. Contrast this with a test-based or domain-based report, where the data are not usually integrated until the end of the report.

How Do I Write Useful Recommendations?

Recommendations are what consumers are waiting for. As we discussed in Chapter 3, consumers such as parents and teachers have a very practical view of evaluations, and although they may be impressed with diagnostic wizardry, they value most professional judgment about what needs to be done to improve things for their children and students. Despite this, recommendations are often ignored because they are too complex or vague, or do not appear directly related to consumers’ concerns.

We have found some school psychologists reluctant to provide meaningful recommendations in their reports. Sometimes this seems to arise from the fear that schools districts will be legally obligated to provide whatever they put in writing. As we have argued, we believe this fear is overblown. So, if we were to state the first point of this section (in the spirit of the themes we discussed earlier), it would be to always provide meaningful recommendations.

In fact, we strongly believe that providing meaningful recommendations that respond to consumers’ concerns is a very good way to avoid legal complications. Although there has been a great deal of discussion in our field for increased involvement by school psychologists in intervention and prevention, many school psychologists continue to function as special education gatekeepers. One of the many problems with this role is that too often parents will attend a meeting where evaluation results are discussed and, unless their child is eligible for special education, the team has little to offer in the way of recommendations for meaningful changes in the child’s educational program. Recommendations are either nonexistent or so weak as to be of little use. If we view this from the perspective of a parent, the concerns that led to the referral remain but we have left them empty-handed. Many times, we have seen this frustration and dissatisfaction lead to requests for expensive independent educational evaluations and other time-consuming legal complications.

The process of crafting meaningful recommendations begins with the identification of the child’s unique pattern of strengths and needs. Given the potential that these recommendations might end up as part of a child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) in one form or another, it is important that recommendations be individualized and respond to unique needs. The clear identification of unique need helps provide the rationale for the recommendation. As you can tell from this and other comments we have made, we strongly believe that generic information is seldom helpful to the reader or, more importantly, the child. This is especially true for generic recommendations that do seem to respond to a particular child’s unique needs. These are both inadequate, legally, and ineffective (Yell, 1998). Even if a child does not need special education services and we are technically free of the mandate to develop an Individualized Education Plan, it is best practice to provide appropriate general education recommendations that respond to that child’s unique needs. Given this, the second point of this section is to link recommendations to clearly identified needs.

Recommendations can range from general to very specific. Where one falls on this continuum can depend on many factors, including your knowledge and training, but also the context of where the recommendations are to be implemented (i.e., is it reasonable for this to be done in this classroom or this school, etc.). On one hand, it can be perceived as presumptuous to be overly detailed and prescriptive about what teachers do in their classrooms. On the other hand, we want to avoid writing recommendations that are so general or obvious that they are of no practical use or, worse, offend the reader by appearing too simplistic (e.g., “Provide multimodal presentation of information”). We have tended to be more specific when we are confident that what we are recommending can be accomplished in a particular setting. This assumes you know your school team and the persons who will implement the interventions. In cases where we know less or have less confidence, we are often more general and offer examples of the kinds of things that might meet the needs we have identified.

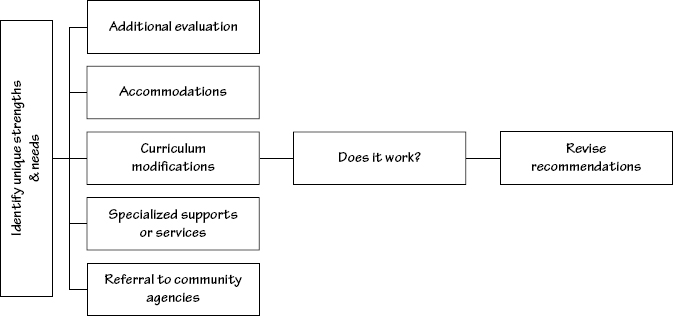

Once a child’s needs have been clearly identified, it is helpful to have a way to conceptualize the kinds of recommendations you might make in a report. One way to understand types of recommendations is to see them in terms of (a) additional evaluation, (b) accommodations, (c) instructional or curriculum modifications, (d) specialized supports or services, and (e) referrals to a community agency or other resource (Lichtenberger et al., 2004; National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities [NICHCY], 2010). Figure 4.3 outlines this problem-solving process as it relates to recommendations. Once a student’s unique strengths and needs are clarified, then meaningful recommendations can be written in the appropriate areas.

Figure 4.3 Thinking Through Recommendations

Recommendations for further evaluation are common when the results suggest that specialists not involved in the initial evaluation conduct additional evaluation. For example, this could arise when your assessment of a child’s verbal abilities suggests the need for the involvement of a speech-and-language pathologist or when you note fine-motor or sensory problems that might be clarified by an occupational therapy evaluation. Another version of a recommendation for further evaluation can also be the suggestion that an area assessed as part of your evaluation be reassessed at some point in the future, perhaps after providing an intervention designed to prevent an apparent weakness from growing into a bigger problem (Lichtenberger et al., 2004).

Accommodations do not require changes in the content of the curriculum but are rather designed to remove barriers and increase access to the general education curriculum. The logic of accommodations is that if a barrier is removed, the child will access the same content and material as other children. Yell (1998) divides accommodations into four categories: (1) classroom accommodations such as preferential seating; (2) academic adjustments such as allowing more time to complete an assignment, allowing a note-taker, or completing fewer items to show mastery; (3) accommodations of tests such as more time to complete a test or giving a student an exam orally rather than in writing; and (4) use of aids or technology such as a text-enlargement device. The goal here is to modify the environment so the child can access the curriculum, without fundamentally modifying the material learned.

Curriculum modifications suggest a change in what is taught or what the student is expected to learn (NICHCY, 2010). Modifications in the curriculum improve instructional match or the match between the learner’s skills and the material taught (Ysseldyke & Christenson, 2002). It can involve remedial interventions or compensatory instruction that teaches needed skills but can also mean changes in structure such as providing a different level of homework or using different evaluation methods for an assignment. Remedial interventions can involve the kind of specialized instruction found in special education but might also involve academic supports in general education such as a supplemental reading program.

Supports or services can be a specialized academic program or intervention such as an individualized behavior plan or a specialized reading program but can also include any of the services regarded as related services in IDEA (IDEA, 2004). The IDEA defines related services as “services that may be required to assist the child with a disability to benefit from special education” (IDEA, §20 U.S.C. 1401 (a) (17)). The law mentions several specific services but also makes clear that this list is not exhaustive (Yell, 1998). Related services are also in the Section 504 regulations but no specific definitions are included in the statute (Yell, 1998). The services noted in IDEA are listed in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Related Services in IDEA 2004

| Audiology Counseling Early identification and assessment Medical services Occupational therapy Orientation and mobility services Psychological services Recreation |

Parent counseling and training Physical therapy Rehabilitation counseling School health services Social work services in schools Speech pathology Transportation |

A referral to a community agency or other resource might include a referral for medical evaluation or treatment or to community agencies that provide specialized psychological treatment or post-secondary transition services. Sometimes local educational agencies have contracts with agencies to provide services such as mental health treatment. Other times, community agencies provide free or low-cost services to the community.

Connecting children and families to community resources is more difficult than it seems at first glance. We have found that this process is made easier if we frontload the parents or child with as much information as possible, including (a) name, (b) phone number, (c) address, (d) contact person, (e) appointment and intake procedures, and (f) required paperwork. Of course, not all of this information needs to be included in a written report but we have found it useful to provide this level of detail in writing at the meetings where the assessment results are discussed.

Remember, the recommendations are placed in the response to the question, “What do we need to do about this?” We have found it best to first identify a need and then offer our recommendations. Sometimes we present recommendations in a list such as the following.

Examples: Recommendations as a List

In other reports, we have found it more useful to incorporate the recommendation into a narrative that responds to the “What do we need to do about this?” question.

Examples: Recommendations as a Narrative

To summarize this section, we recommend that you always offer meaningful recommendations, link them clearly to unique needs, and consider the child’s needs for each of the following types of recommendations of (a) additional evaluation, (b) accommodations, (c) instructional or curriculum modifications, (d) specialized supports or services, and (e) referrals to a community agency or other resource.