|

13 |

Defining Interactive

First of all, we need to define more closely what we mean by the term “interactive”. Although interactive media were enabled by the convergence of computer, video, and audio technology in the same digital environment at the end of the twentieth century, there are previous examples of interactive structures in our culture. Although the term “interactive” is new, the phenomenon is not. We can even see this before the Gutenberg era of print media, which is only now being displaced by information technology. Although we associate books with print technology, a book is a piece of technology that preceded the printing press. Medieval monks wrote books with numbered leaves of paper or vellum bound together in a sequence so that the reader could keep the printed matter in a compact space and access any part of it very readily. Consider some of the alternatives—clay tablets, parchment scrolls, or palm leaves sewn together—all difficult to handle and absolutely linear. Those more primitive technologies use the writing medium in a sequence that is analogous to a straight line. You have to move along it in one direction, forward or backward, starting at the beginning or at one particular point. If you are in the middle of a scroll and you want to consult the beginning, you have to roll the scroll backwards, just as you have to rewind a videotape.

In the fifteenth century, the printed book was a stunning piece of cutting-edge technology that changed European civilization and had a revolutionary impact on social and political culture somewhat like the computer and the Internet do today. Books and magazines will not disappear soon because this technology is still very effective. Consider this book you are reading now! In a flash you can look at the table of contents, the index, or the glossary and go back to the chapter you are reading. In addition, of course, you can open a book at any chapter. Surely, this is the beginning of user input—namely, interactivity. Early on in the five hundred year history of printing this structural design was exploited to make dictionaries and, later, encyclopedias. This type of book is nonlinear in design. You open it at any point of alphabetical reference and you move between pages that are cross-referenced. This is also the logical model for hypertext that is now integral to the World Wide Web. Dozens of reference books, including the commonplace telephone directory, were never designed to be read in a linear fashion, but consulted in an interactive fashion. Did you ever meet anyone who reads the telephone directory, the dictionary, or even an encyclopedia from end to end? Can you imagine a telephone directory or an encyclopedia as a scroll? Most of the knowledge in the ancient world was recorded on these primitive handwritten media.

Interactive means that the reader or user can make choices about the order in which information is taken from the program. You cannot get information from the Yellow Pages without making choices. You cannot progress through a web site experience or a game or a training program without making menu choices or activating a link that starts a new chain of choices. Whereas the information in a reference work is pretty much on one predictable level, the experience of a game or a web site is an open-ended discovery. It is not only about a number of choices but about permutations and combinations of choices. So the number of choices becomes mathematically very great. This is becoming problematic for some giant web sites. Users get lost. Sites have to incorporate search engines. The paramount issue of the day is how to design choice for the user that is efficient and clear so that hits on a web site lead to burrowing and deep exploration.

Linear and Nonlinear Paradigms

Narrative works, whether in poetry or prose, appear to be linear in construction. Drama is linear because, like music, it plays out in time for a specific duration. We saw that one problem of writing screenplays is the linear play time that drives how you think and write. However, epic poetry from ancient time has usually been based, as with The Iliad and The Odyssey of Homer or the Sanskrit Mahabharata, on a huge mythological background web of stories that is not strictly a linear narrative but a cluster of interlinked narratives. Even European works such as Boccaccio’s Decameron, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, or the peripatetic novels of the eighteenth century, such as Fielding’s Tom Jones or Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, explore structures that are not end-to-end linear but layered or multidimensional and not necessarily chronological.

The Bible is an interesting example of both types of structure. Although the Old Testament is a broadly chronological sequence recording the history of the people of Israel, starting with Genesis, the New Testament is principally four parallel narratives. The Torah is still written out as a scroll and read sequentially throughout the year in a linear fashion. The scroll is housed in the Ark of the Covenant and worshiped as the word of God in synagogues. The Christian Gospels were recorded in a nonlinear format—parallel stories about the same events in the life and death of Jesus. The structure suggests the difference in the spiritual teaching. The former is based on 613 commandments elaborated in centuries of commentary to prescribe every detail of life in a tribal existence. The latter is based on a single commandment that is universal. The Gutenberg Bible, the vernacular book that launched the era of print media and changed the religious and political structure of Europe, embodies the two narrative paradigms.

Interactive narrative paradigms have evolved rapidly with the advent of video games. This new dimension to storytelling makes the audience part of the story. In the most sophisticated examples of the genre, the player of a video game interacts with an imaginary world, determines actions for characters and influences the outcome. The development of artificial intelligence opens up rich new opportunities for interactive illusion.1 At the start of the 21st century, we are experiencing the burgeoning of information technology that alters and develops preexisting forms of narrative and exposition.

It seems reasonable to argue that the human brain does not function in a linear fashion. It is more akin to a computer processor that multitasks and uses different types of memory. Physiologically, the human brain processes different sense impressions with different cells in different areas. Visual sensation is processed in the visual cortex and auditory sensation in the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe. Touch, which enables interaction through the mouse and keyboard, is processed in yet another sensory area of the cortex. We all know how we can hop between mental tasks and suspend one operation while we process another. Indeed, our lives seem to depend on being able to do this more and more now that we have the tools to exploit this potential of the human brain. All our memories, all our knowledge, and all our consciousness coexist with random access. We use them somewhat like a relational database but without the same efficiency or speed. We can even think and do two things simultaneously. Not only do we have to chew gum and walk at the same time, we have to multitask all day long. We drive a car, listen to the radio, drink coffee from a mug, plan the events of the day and talk on a cell phone. The way the human brain manages this reality stream and programs the actions that follow provides a nonlinear model. Linear media increasingly make use of multiple information streams. Television puts text titles on screen, or the stock market ticker under the news at the same time as the anchor is talking and the picture moving. It uses picture in picture so that the eye and brain must sort multiple streams of information simultaneously. Many channels have preview pop-ups of the next program in the corner of the screen so that the viewer is engaged in program planning while engrossed in current viewing, even of dramatic material that calls on the audience’s “willing suspension of disbelief” (Samuel Taylor Coleridge), something that would never occur in the viewing experience of film in a movie theater.

Combining Media for Interactive Use

Although we have probably always had nonlinear imaginations, we have not always had nonlinear media nor the tools to make them interactive. Our entire linguistic education encourages us to think, read, and write in a linear fashion going from left to right and from top to bottom. For traditional script formats for television, film, and video, we had to write for two media that can exist independently—sound and vision. Now we have additional media—graphics, animation, still photos, and text. So just as it is a bit of an adjustment to write a script with two or three columns, writing for interactive media will require a new layout to accommodate not only more elements of media production but also the nonlinear form and the interactive possibilities of the program. This is true for both interactive instructional programs and for games and interactive narrative. Because a script is always a blueprint or a set of instructions for a production team, we have to figure out how to express the interactive idea for the makers to build in that structural possibility.

What comes first: the chicken or the egg? Do you design the interactivity first or do you write the content? This is the key question for understanding the problem of interactive writing and design. This differentiates the challenge of writing content for linear media and writing content for nonlinear and interactive media. In the first, the presentation of content is predictable in flow and direction. Sequencing is critical to all the writing we have discussed so far. Suddenly, sequencing doesn’t mean a thing because the user or player is going to choose the order of multiple possible content sequences by mouse click or button press. We are creating menus of choice. To continue the metaphor, we are used to starting with appetizer, soup, starter, going on to the main course, and finishing with dessert. We can serve wonderful sit-down meals in this way, whereas interactive experience resembles a buffet. You eat what you want in any order at any time. Some people may want to eat dessert first, or stay with starters. Like all analogies, this one is limited.

The point is that the relationship of one scene to another, one page of script to another organizes the structure of the resulting film or video. For interactive media, there is no such relationship. The order in which you write down something does not reveal the final order of the program or even the order in which the user can access it. You can write words to be recorded as audio, pieces of text for display on screen, or images to be created by graphics tools or shot on video, but this has no necessary relationship to the way all these elements will be arranged in an interactive program. Nor would these individual pieces of writing express the interactive relationship between them. That interactive potential has to be conceived, designed, written down, or represented so that it can be made or rather programmed.

You have to know that an interactive design will work. Interactive content cannot meaningfully exist without interactive design, at least only to a degree. How do you prove that the interactivity will work whether it is on a web site or a CD-ROM? You have to write that interactivity into computer code that will make it happen. You have to use an authoring tool. The content or “assets” as they are often called— text, graphics, video, or animation—cannot be created first before design. It may not always be clear at the outset what media you need. These bits of content that might be greater or smaller or added on later are written as descriptions of what is going to come. The final result, what you are purveying, is an interactive click stream or a potentiality of interaction. You have to model a kind of prototype. The plan for this is difficult to describe in prose. A diagram seems to explain it better. This diagram is known as a flowchart. A flowchart can map the interactive idea more efficiently than lengthy descriptions of multiple opportunities for user choice.

However, the flowchart does not describe the content—the text, the dialogue, the pictures, or the video clips. Out of each node on the flowchart comes a piece of writing that describes a graphic, a photo, an audio element, a piece of video, or text. So you have to think in two dimensions. One relates to the content of a particular piece of media. The other relates to your overall interactive purpose across the whole. Let’s illustrate all this by some communication problems for which an interactive multimedia design would be a solution. We need to recall the seven-step method:

![]() Define the communications problem. (What need?)

Define the communications problem. (What need?)

![]() Define the target audience (Who?)

Define the target audience (Who?)

![]() Define the objective (Why?)

Define the objective (Why?)

![]() Define the strategy (How?)

Define the strategy (How?)

![]() Define the content (What?)

Define the content (What?)

![]() Define the medium (Which medium?)

Define the medium (Which medium?)

![]() Write the creative concept.

Write the creative concept.

Until you answer these questions, you cannot intelligently decide whether an interactive medium is the solution. Defining the objective is going to weigh heavily in making this decision. Many producers despair of corporate clients who come in and say we want a web site or we want a CD-ROM without knowing the communications problem and the objective. They see that rivals and competitors have these products, so they want one. It is essential to start by looking at the communication problem, rather than starting with the communication medium and then finding the solution that will use the medium.

A video game is an exception to this analysis because it is interactive by definition and by its very nature. If you are designing a video game, you do not wonder whether it will be interactive; you know it has to be interactive. You spend your energy defining the target audience closely and thinking about a strategy to make it different, new, or appealing to that audience. The objective might be to excel in graphic realism or to innovate in streaming video or to create a totally engrossing imaginary world.

Let’s start with the DVD that accompanies this book. The problem is that beginning scriptwriters have difficulty seeing the relationship between words on a page and the finished product. They also have difficulty translating a visual concept such as a shot or an image into a descriptive scripting language. Descriptions and illustrations interrupt the flow of reading. Wouldn’t it be an advantage to be able to show a script and have a video clip to illustrate the scene? Wouldn’t it improve understanding of scriptwriting terminology describing camera shots and transitions if you could read the definition and see or hear an example? An interactive multimedia lexicon is a solution to a need to understand new concepts. The objective is to make scriptwriting terminology more accessible to a target audience of college students who are not always good readers and who might not retain the concept by reading a definition. The strategy is to make it easy to use.

Consider the following initial proposal document that is the formal beginning of the project:

Design Objective:

The main objective is to provide an interactive tutorial for scriptwriting terminology and its use. The idea is to provide a lexicon that combines text, image, and sound to explain each term. An efficient interface and clear navigation are important so that the module is easy to use. The user can select terms in any of the three main areas—camera, audio, and graphics—to increase familiarity with scriptwriting terminology and have a better understanding of the industry-wide conventions for this type of writing. The strategy is to create an easy interface with interactive links that make all definitions two or three clicks away from any place in the glossary.

Navigation:

The flow is hierarchical with links so that the user has an opportunity to connect traditional text definitions via hyperlinks to illustrations in the medium itself—video, graphics, and audio. Each page has a button link to the other branches so that the user can move at will between topics. Each page is designed to offer a choice to a deeper level with button or hyperlink options that move the user through branching to a graphic illustration. The hierarchy has three levels and then a return back to the top or a link to another branch. There is a link to a complete alphabetical lexicon that itself links to every definition, e.g., “Medium Shot”.

Creative Treatment:

Although the content is educational, the graphic style establishes a bright and user-friendly environment with clear navigational choices to click through the bank of information. Each link has a visual change such as a new color or a rollover effect together with a sound cue to support the navigational choices. Apart from the text that defines the term selected, we see a choice of visual icons for each type of illustration that embody links to that illustration. For example, the camera movements are represented by a camera icon, the camera shots by a TV frame icon, the audio by a speaker icon. When an illustration is a QuickTime movie, we set it in a quarter frame with relevant text. The usual player controls enable us to play, rewind, and stop. Likewise, audio illustrations have player controls including volume.

Text definitions travel with the navigation from level to level. Choosing camera leads to a choice of three sub-topics: shots, movements, and transitions. So “movement” is added to the camera identity of the frame. Then at the next level, the specific movement is added: “movement—PAN.” A short definition is fitted into the layout with a movie frame and controls so that the movement can be seen as live-action video. In this way the information is cumulative. Links to web sites about scriptwriting and productions could add another dimension but would also distract from the central purpose, which is instructional.

The written proposal is a necessary start. It does not solve the many problems of design but rather states what they are. It does not enable you to experience the navigation, which is the key to the nature of interactive experience. In fact, between proposal and production many things changed as the reader can verify by using the DVD at the back of the book. The provisional flowchart included an interactive game that had to be abandoned because it would not really work in practice.

One of my students proposed an interactive project on national parks, something like a kiosk, CD-ROM, or web site. The idea appeals immediately. The Department of the Interior (specifically the National Parks Service) would be the theoretical client. The project provides a solution for dealing efficiently with public inquiries, but it goes even further and anticipates a need to promote tourism. Much of this type of information has no linear logic. Geographical location, wildlife, and recreational facilities need to be accessed through some kind of interface. The hierarchical content becomes enormous. The amount of content was far greater than ever imagined in the written proposal. In this case, the organization of the interface determines the content. An excellent example of this type of interactive guide has since been created called “The Adirondack Adventure Guide.” You can examine the design document in detail.2

![]()

Many projects get out of control and cannot be finished because the design-versus-content relationship is not understood at the outset. In a professional world in which you are paying graphic artists, videographers, and sound engineers to create assets at great cost, you cannot afford to ask for content in a script phase without an interactive design. What you are selling or what the producer is selling is the interactive experience, not the content per se. It is rather a way of experiencing and using the content.

It is probably true to say that there is no industry-wide standard script layout for interactive programming. The layouts are still being invented to some extent. You will come across a patchwork of script formats. For example, if a game involves dialogue, then a scriplet, or mini script, similar to a master scene script, might be useful for a dramatized section. An audio recording might be prepared like a single-column radio script. A description of a graphic can be a simple paragraph, but sooner or later, a graphic is going to have to be sketched in storyboard format. Finding ways to lay out the screens or sequences is probably manageable by common sense. You really need to group the different kinds of assets together. You need a shot list of all the audio and a folder with those scripts numbered or indexed to relate to a plan for the navigation. The same is true for video and graphics. The relationship between the scripting elements cannot be understood without this plan of navigation that explains the interactive sequencing and menu choices that must be built in with an authoring software like Macromedia Director. Although you need a written design document describing the objective, the interface and how the navigation will work, you also need a new kind of document which is a diagram of the navigation. It is called a flowchart. In short, you cannot write much specific content without a flowchart because of the nature of the production process. The sequence is:

![]() Write a needs analysis defining the communications problem for the client.

Write a needs analysis defining the communications problem for the client.

![]() Write a creative proposal demonstrating that interactivity is an answer.

Write a creative proposal demonstrating that interactivity is an answer.

![]() Write a design document describing the interface and how the navigation will work.

Write a design document describing the interface and how the navigation will work.

![]() Map the interactive navigation by creating a flowchart.

Map the interactive navigation by creating a flowchart.

![]() Create storyboards for graphics/animation.

Create storyboards for graphics/animation.

![]() Write key scriplets for video, audio, text.

Write key scriplets for video, audio, text.

The key step is number three: navigation. It is difficult to describe it thoroughly in prose. Should a writer be drawing? In the new media world, the role of writer is breaking down, or the role of writer is expanding, depending on how you define your role. Is the writer the designer of content and the designer of the audience interface with that content? The answer ought to be yes.3 The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain maintains “that writers, rather than designers, should be composing the scripts for games.”4 This suggests that designers are writing and that writers need to encompass design.

The capacity to think about the final experience and media result before production resources are committed to the project has always defined the role of the writer. The writer has to have a grasp of what interactive code and computer scripting language can do to describe interactive possibilities. The carriage builder has to become an auto worker. It is a symptom of change in the media landscape.

It seems awkward to introduce drawing, storyboarding, and charts into a work on writing for visual media. Writers do not necessarily have artistic skills. What if you cannot draw? If you do not conceptualize navigation, you take a backseat to some other member of the team. The question is whether the writer becomes a co-designer or just a wordsmith called in to write dialogue, commentary, or text. Perhaps collaboration is possible. Writers could also be designers and vice versa. There is a parallel between this and the writer/director relationship in linear media. Writers lose control to directors once production begins.

So what enables you to think about, conceive, and express navigation?

Branching

The easiest concept to grasp is branching. The metaphor is a tree that starts with a single trunk and then grows branches, which in turn grow smaller branches until there are thousands of twigs with leaves on them. The directory structure of a computer hard drive in most operating systems is presented to the user in this way. You navigate through directories and subdirectories until you find a specific file. This is known as a hierarchical structure. It is not an interactive structure because you can only go backward or forward in your click stream. You find this out if you construct too many folders and subfolders. Computer directory structures can be very unwieldy unless you have a tool like Windows Explorer to look down on the branching structure from above and navigate around it. Those who remember MS-DOS will remember the tedium of switching drives and changing directories to find a file.

You are probably familiar with organizational charts that show a chain of command or a chain of relationships. The limitation of this model as an interactive plan is apparent as soon as you go down or up a few levels. The number of branches increases geometrically. Getting from one branch to another is workable if you look at a page because your eye can jump from one part of the hierarchy to another. If the structure has embedded sequences that are hidden from view through menu choices, we are stuck with a tedious backtracking procedure that is like turning a book into a scroll. The depth of certain web sites leads to real navigational problems. To return to the model of a tree, we need to be like a bird that hops or flies from branch to branch at will, not an ant that has to crawl down one branch to the trunk in order to go up another branch. Hence, we create hyperlinks between branches—active buttons or screen areas that switch us instantaneously to another page or another file. The cross-referencing can become very complex. You cannot link everything to everything else because the permutations and combinations would quickly become astronomical. This is the point at which you begin to design interactivity. You start to think about those links that will be either indispensable or useful. This thinking has to be set down. It is not just a crisscross of links, it must also be an interface that reveals the intention of your interactive design. You need to invent a visual metaphor that immediately communicates the organizing idea. This is the visual imagination at work. Once again, can you do it in prose? Partly!

Although it overlaps graphic design, inventing and organizing content and designing the look are two different tasks. The organizing idea could be that you see a bulletin board. Each of the notes posted on it is an active link. For another example, you have a room. In this room each object has a visual meaning and links to the other areas of content. Doors or windows can lead to subsets of information. Obviously, the visual metaphor should relate to the content, the objective, and the target audience. If you are designing learning materials for children, you might want cartoon animals in a zoo or a space fantasy. If you are creating an interactive brochure for a suite of software tools, you would look for a classy and clever interface (say a stack of CD-ROMs that slide out when you mouse over) that expresses something unique about the applications. Once again, can you do it in prose? Partly!

Computers now depend on visual metaphors codified as icons to communicate functions: a trash can for Macs, a recycle bin for Windows; the hand with the pointing finger; the hourglass; the hands turning on a clock face; the animated bar graphing the amount of time left for a download. The visual writer has a talent that works with images projected on a screen and should be able to propose visual metaphors for navigation and organization. In fact, the best writers can manage content and communicate ideas precisely through visual metaphor and visual sequencing. So the visual writer has an imagination that can migrate from the linear to the nonlinear world. It is probably the key to your professional future and essential to a lot of media creation in the years to come.

You know the problem. Again, witness certain web sites, particularly university web sites! You spend hours trying to find your way through the maze. You also have to grasp the organizational idea presented in the home page. Web site design is a problem of visual organization but also of navigation. If you want to express an interactive idea, limiting yourself to writing only a word script would be like tying one hand behind your back when you can also draw a diagram with a purpose-built computer tool.

We can represent the linear paradigm as a piece of string. We thread beads— events, scenes, chapters, sequences—on the string to create linear programming. Once we break with the linear world, we have no specific model as an alternative. We should consider other analogues or metaphors of organization that will lead us out of linear into non-linear. For example, take the wheel! It is a non-linear paradigm. It has a hub, spokes and a circular rim. There is no beginning and no end. You can go from the center down a spoke (think link!) to any part of the circumference and vice versa. A variation would be a hub with satellites. You can combine branching with other structures after one or two levels, somewhat like a plan for an airport. Then there are pentangle patterns, which join up all nodes to all other nodes. A narrative journey can follow parallel paths with alternative routes, useful for interactive video games.

A flowchart is a schematic drawing that represents the flow of choices or the click stream that a user can follow (see Figure 13.1). If you don’t plan it, it won’t be there. Although you can compel the user to make a choice, you do not know which choice. Although the user may think of choices that you haven’t, he cannot insert new choices into the finished interactive program. If a link is not there, the user cannot put it in. He cannot build his own bridges or impose his own interactive design on a program that is already authored.

Figure 13.1 Flowchart Symbols

Interactive multimedia designers have come to think of the flowchart as the first step in designing interactive choice. This map or diagram of the interactive click stream has become the ubiquitous planning document for interactive design. The problem of communicating the flowchart has resulted in a convention that reduces verbal explanations of choice to symbols. In fact, you can use the tables and boxes of a word processor to create flowcharts. More versatile tools exist such as Inspiration, Smartdraw, Storyvision, and StoryBoard Artist. Each has a dictionary of shapes and symbols and drawing tools that enable anyone to create a flowchart How else are you going to design navigation?5 These software applications were invented to cope with the complexity of relating navigation diagrams or flowcharts with multiple storylines to the text that describes scenes. You are able to manipulate text files and graphics in a way that is beyond the scope of word processors. Movie Magic also has a template for an interactive script format that you can consult in the Appendix.

![]()

Storyboards

We saw that commercials and public service announcements made use of storyboard techniques to lay out clear visual sequences for clients. Storyboards are very useful for graphics and animation sequences (see the First Union example on the DVD). Computer software exists that enables the non-artist to visualize directly in the medium and design motion sequences for animation and live action. Storyboard Artist is a software program that allows you to create animated sequences out of a repertoire of characters and backgrounds that you can play as a movie.

Authoring Tools and Interactive Concepts

To understand interactivity, it is helpful to grasp how it is constructed. All of the assets—video, graphics, text, audio—have to be assembled as computer files and set into an interactive script that plays them when the user clicks on a button or link. So all the scripts or scriplets of individual pieces of media do nothing until you orchestrate them into an interactive scenario by means of an authoring tool. This is a software application that writes a scripting language with commands in computer code that make the various files display on screen in response to user input from the mouse. You cannot author this interactivity from a script easily unless it is expressed as a flowchart. The way an authoring tool works illustrates exactly why scripting content in segments does not express the interactivity.

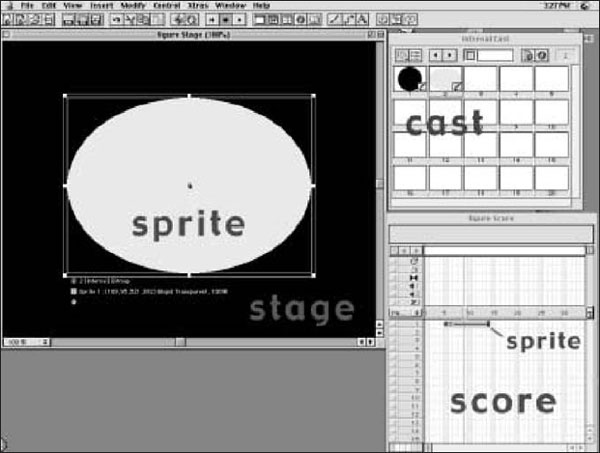

The professional authoring tool of choice for fixed media is Macromedia Director.6 Video game authoring tools or programming software are often proprietary, such as Electronic Arts’ RenderWare. The function is the same, which is to encode the interactive choices available to the player or user. In Macromedia Director, all the graphics, movie clips, audio clips, and text exist as separate cast members that are called onto the stage, that is the screen display, as “sprites”. Each cast member, when it comes to the stage, becomes a sprite, which occupies a frame in a complex score (see Figure 13.2). Each sprite and each cast member can be assigned behaviors that tell it to respond to a command such as “mouse enter” or “mouse down”. The way the score plays, with its pauses for user input that jumps from one screen to another, is controlled by a computer scripting language called Lingo. This code makes the events happen in response to user input—clicking on a button—or a rollover or a link to a web site outside the CD or DVD. The sophisticated coding of the score at the high end requires a programmer, somewhat like a movie or a video requires an editor, to create the final shape of the program by writing the Lingo code which tells the computer what to do.

Figure 13.2 An example of Stage, Cast, Sprite, and Score in Macromedia Director showing their relationship.

From Director, Macromedia derived a web animation tool called Flash that copes with frames that move and layers of visual elements. The same software developer devised Dreamweaver for web site design so that you do not have to master HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language), which is the open source computer code with which most web pages are constructed. It is the primary computer language of the World Wide Web. There are many other web page authoring tools that put the web page designer at one step removed from HTML; nevertheless, webmasters still need to know the actual code that makes the pages work, both for the execution of design and for maintenance.

To summarize production: step 1 is to assemble the media elements; step 2 is to position the media elements on stage or screen display; step 3 is to write the interactivity by means of a scripting language; step 4 is to render it as a stand-alone program that will play from a CD-ROM or DVD on any computer platform, or to translate it into HTML compatible code so that it will run on a web site.7 Macro-media Director can also publish a Shockwave version of an interactive program, which can be embedded in an HTML document and played on the web.

It probably makes sense to divide the world of interactivity into two broad categories. The first is fixed interactive, including storage media such as CD-ROMs, DVD-ROMs, and proprietary disks or cartridges that companies like Sony and Nintendo use for video game consoles. When the program is completed, the producer publishes it, manufactures it, and distributes it in physical form. To change it means going back to the authoring tool and burning a new glass master from which to manufacture new disks. That is what we had to do to revise the CD that goes with this book for this second edition. In fact, we have changed from a CD to a DVD to gain real estate for all the new media content.

The second category is web-based non-fixed media, or interactive pages, uploaded to a server that is linked to a network. Most of the time the network is the internet. Then that site becomes part of the World Wide Web, which is a construction of unlimited connectivity between servers on that network. In practice, the network on which the non-fixed media work could also be a LAN (local area network) or a WAN (wide area network) not connected to the public internet or part of the World Wide Web. Many corporations and organizations maintain their own networks that work on the same principle as the internet, but you and I have no access to them. In fact, the internet itself was originally the growth of a Pentagon WAN (called ARPANET) to decentralize command functions, which was then used by the defense establishment and the research establishment to send documents and messages. The internet is simply a network that is not owned by anyone and to which anyone can have access so long as they can connect their computer to a portal, or an internet service provider (ISP). Companies that maintain the servers and the infrastructure of the network (fiber optic cable, satellites, microwave circuits) and provide access to this network charge a tariff and rent space on their servers for the web page files to reside and be accessible to browsers.

All this background is perhaps more than we need to know as writers. However, because of the relatively recent emergence of the internet, it seems wise to ensure this understanding so that we can see how writing is different for different interactive media, just as writing for movies is different from writing for television or video. The difference comes about because of the nature of production and distribution in each. Fixed and changing interactive media rest on different computer languages. One can be translated into the other, but there is a different functionality between a closed disk with a predetermined audience and use and a computer file open to anyone in the world with a computer and a connection to the internet. This difference is dramatized by the problem of hackers, who can enter and modify those files, whether on a server or on your computer. This is not true for a manufactured disk.

Now we should consider what kind of communication problems find better solutions in interactive media. Always remember that the writer is paid to think as much as to write. So the question arises whether traditional linear video will do a job better, or whether it is better to create an interactive solution. To think clearly about the uses of interactive media and understand how to write for them, we need to observe to what uses they are put. The uses are not always confined to either fixed or fluid media. For example, video games can reside on a web site or be distributed on a disk. Multiple users can access a web-based game, whereas only those with access to the player console have access to a game on fixed media. The same is true for, say, an interactive training or educational program. Broadly, the uses of interactive media are similar to linear media except that the new capability of interactive media allow some new applications. You can’t use linear media for a kiosk in a mall, for example, where you want to provide shoppers with an interactive guide.

Multimedia Components

Although the writer is not directly concerned with the production issues of making sure a program works cross-platform or is compatible with the average computer speed and RAM, it is wise to be aware of them. Any knowledge of how graphics, animation, and authoring tools work changes everything for a writer of interactive media. The more you know, the more intelligently you can write. If you make something interactive on Macromedia tools like Dreamweaver or Director, you get a much clearer idea of what the process is and what you need on paper as a planning document before you create assets or start programming. Just as a screenwriter should understand the language of cinema and how the camera frames shots and how shots can be edited, so a writer of interactive media would learn from using an authoring tool.

The interactive world is made up of several components: text, graphics, animation (2-D and 3-D), still photos, video, and audio. Each of these assets is produced independently with a different production tool. Some, such as text, graphics, and animations, can be created within the computer environment. Still photos, video, and audio originate in other media and have to be produced externally and digitized as computer files so that they can be edited with sound editing software and video editing software.

Finding a Script Format

The jury still seems to be out on what script formats are acceptable to interactive media producers. No clearly defined format has come to the fore such as those that exist for the film and television worlds. Published books that cover the subject in most depth cite a number of variants that leads one to think that the format can be tailored to the writer, the production company’s established format, and the interactive nature of the project. The Interactive Writer’s Handbook cites thirteen key elements in a design document. Some of them, such as a budget, schedule, marketing strategies, and sample graphics, require input other than the writer’s. There is an area of overlap between layout, graphic design and visual writing. Graphic design is the technique of visual communication, not necessarily the visual conceptualizing of content that precedes it. The design document dreams up the idea and finds a visual solution to a communications problem. The graphic designer chooses fonts, colors, layout, and orchestrates the look and coordinates the esthetic detail to make the idea work. Writing precedes graphic design, which is a facet of production and execution of the vision. Visual thinking, which is a way of construing the content with an organizing idea, precedes conceptual writing.

Visual writing would come into play for a concept, a story summary, character descriptions, and an interactive screenplay. Where characters and drama are involved, a modified master scene script works very well to describe setting, characters, and dialogue. When characters have different responses depending on choice, the format has to indicate a numbered sequence of choices. Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? has encounters with characters in different locations. Different interactive choices produce different responses from the characters, which give you information and clues. So in a given location, the character’s replies are going to have to be numbered and related to where the player clicks on active parts of the screen. So the script format is going to vary with the type of project.

Conclusion

Most writers of traditional media seem to be afraid of interactive media. It dethrones the writer to some extent. Linear media present the writer with a clear task, a clear role, and a definite authorship from which all production proceeds. Interactive media do not make the script the premise of the product. Writing is necessary to flesh out a design. A number of different writing skills can be employed in the same production. One interactive producer explained to me that he uses three kinds of writers: one for text on screen, one for concept, and one for dialogue or voice-over. Sometimes, he gets all three in one writer. This is why the writer is not the author of interactive media in the same way as movies or television.8 Collaboration is, has, and always will be, indispensable to creative media program content. It seems even more true for interactive media because of the very nature of the medium. We now need to examine more closely the uses to which interactive media and interactive writing can be put.

Write an organization chart to document the chain of responsibility for an organization such as a company where you work, a college or university, or a club or other organization to which you belong.

Write or draw a logical branching sequence for an interactive CD on (a) pasta, (b) automobile racing, (c) solar energy, or (d) cats.

Devise visual metaphors for the commands, “Wait!”, “Think!”, “Danger!”, and “Important!”

Describe the navigation in prose for an interactive CD on (a) cooking with pasta, (b) automobile racing, (c) solar energy, or (d) cats.

Write a flowchart for a simple game in which you have to click on a moving circle to score points, which are then displayed on screen.

Design an interactive multimedia resume for yourself.

Describe an interactive game based on a world concept. Describe the main characters and what the objective of the game is.

Write a proposal for a training CD-ROM that teaches the highway code for your state with an interactive test at the end.

Endnotes

1See the discussion on the International Game Developers Association website: http://www.igda.org/writing/InteractiveStorytelling.htm.

2See Writer’s Guild of America West’s website at http://www.wga.org/

3A sample of opinions by writers who have worked on interactive projects can be found in Interactive Writer’s Handbook, 2nd edition, by Darryl Wimberly and Jon Samsel (San Francisco: Carronade Group, 1996).

4See http://cgi.writersguild.force9.co.uk/News/index.php? ArtID=147.

5See Smartdraw at http://www.smartdraw.com/exp/ste/home/ and Storyboard Artist at http://www.powerproduction.com.

6See Phil Gross, Director 8 and Lingo Authorized 3rd Edition (Berkeley, CA: Macromedia Press, 2000).

7See Timothy Garrand, Writing for Multimedia, 2nd edition (Boston: Focal Press, 2000) and also Darryl Wimberly and Jon Samsel, Interactive Writer’s Handbook, 2nd edition (San Francisco: Carronade Group, 1996) Larry Elin, Designing and Developing Multimedia: A Practical Guide for the Producer, Director, and Writer (Boston:Allyn & Bacon, 2000).

8Of course, the French new wave cinema has always asserted that the director is the auteur of the film. That is hard to see if the screenplay is an original.