Step 4

Find Help

Questions to get you started:

Who helps you?

What are all the different ways that people support you?

How can your friends, family, and coworkers help you make a change?

I used to have a problem. I didn’t know when to keep my mouth shut. I challenged authority more than was healthy for me or my career. Fortunately, someone helped me overcome my behavioral addiction. He was a colleague of mine and also a good friend. At first, he just pointed things out to me after they’d happened. We’d have lunch after a team meeting and he’d say to me, “Do you know that you shouldn’t have said that the new policy is stupid?” I’d tell him that I realized it after the fact, and that would be that. We’d have a meeting. I’d say something challenging to my manager or about senior management. My friend would admonish me for it afterward, and I’d keep on doing what I was doing. I was finding it beyond my power to stop the behavior on my own.

66 Then he did something different. He sat next to me in a meeting, and every time he saw me getting frustrated, he would step on my foot. He knew the signs that meant I was about to say something detrimental to my career. It worked. It stopped me and forced me to think about what I wanted to say. I still challenged things when I felt strongly enough about them, but my challenges were more thoughtful and less antagonistic. We should all be so lucky to have friends who voluntarily step up to support our needs. The simple truth is that significant change requires help.

What do you need to consider in order to find help?

In this section we will explore various ways to build a network of support to help you break your self-addiction. Step 4 will address:

- The value of support

- How trust plays into support

- Who your possible supporters could be

- What roles they can play

- How some people play contrary roles and undermine your efforts to change.

The Value of Support

You will benefit from support in many ways. Supporters can offer you feedback, both critical and positive, on how you are doing relative to your goals. They can also provide you with unique perspectives. They can turn you around when you get down on yourself and point out your successes. Your supporters can ground you and help you see what is really happening in your change efforts.

A partner in your change efforts can also challenge and push you to greater performance and help you come up with new ideas for how to perform better in the future. Alcoholics Anonymous uses this support to guide its members. When a new person joins, he is encouraged to find a sponsor. The sponsor is someone who helps 67 the new member navigate the steps of the program and manage the situations that could lead to relapse. Without the sponsor, the program wouldn’t be nearly as effective.

Also, when you are alone and you fail to achieve your goals, there is no one with whom you can share your disappointment. When you involve other people, you create an important motivation that could help you make your change. People who are counting on you or rooting for you help you remain accountable and motivated so you work harder to avoid disappointing them. I’ve known many people who wouldn’t think twice about disappointing themselves, but disappointing other people would cause them tremendous angst. Building a support network can help fuel this type of motivation.

There is also a risk when you lack supporters that your success goes underappreciated. You can’t expect that the first time you change your behavior, everyone around you will notice your change, stop what they are doing, and give you a standing ovation. In all likelihood, you will be the only one who notices. Karen, The Pushover, tells her story of this experience.

The Pushover

When I committed to giving up my pushover behavior, I thought that people would really take notice. I remember a meeting I had with my department. We would have these big meetings with my boss and all of my peers and all of the people who reported to us. My boss always had new work to assign in these meetings, and he always asked for volunteers. I was always the first to raise my hand, and my team had started to dread these meetings because of that. During this meeting I counted the places where I would have jumped to volunteer in the past. There were 10 different times that I would have taken on a thankless task or project.

After the meeting, I looked for any sign of recognition from my team, any hint that they realized that this discussion was different. In the end, they didn’t seem to notice anything. I wanted to stand up and shout at them, “Don’t you realize how different things are? Don’t you 68 understand how hard I’m trying for you?” But they didn’t. It was really disheartening at first. Then I tried to see it from their perspective.

They’ve got this boss who’s always been a pain in the neck. I offer up their time even when they’re stretched thin. I ask them for “favors” because I somehow think that will make it okay that I’ve once again agreed to something that will make their work miserable. I put off difficult decisions because I don’t want to upset anyone. Of course, that just makes people more upset.

All of a sudden a conversation went by where I didn’t volunteer their time for everything. To them, this was an aberration. Maybe they thought I didn’t get enough sleep last night and wasn’t really listening. Maybe they thought that I was having family problems and was distracted during the discussion. Maybe they didn’t think anything at all, because they didn’t even notice. I expected them to do cartwheels because they’d had one good meeting with me. Meanwhile, for them, this was only one good meeting out of the last 100.

Karen thought that any change in her behavior that she noticed would also be noticed by those around her. She assumed that the same people who were frustrated with her would turn around and recognize and appreciate her for taking her first steps to make their situation better. The truth is that when you try to change, you will be much more aware of any minor adjustments in your action than those around you. The people around you are used to seeing you in the way they always have seen you. It is only once you make big changes and sustain them over time that others will see your progress and give you credit.

One opportunity that you have is to bring people into your process. Let them know what you are doing. Then they will be more on the lookout and more likely to see the changes you make. It is important to celebrate your successes along the way. You will be much better able to enjoy the moment if you have partners with whom you can share your triumphs. 69

The Trust Factor

We will look in more detail at the different types of partners, how to identify people to help you, and how to ask those individuals for support. However, before we get to that, it is important to understand how trust issues play into these relationships. By telling people about your commitments to change, you become vulnerable. You are vulnerable because you have shared that you have a flaw and have opened yourself up to criticism if you fail to change. At this point, you may even be wondering, “Why should I trust other people with my change?”

The truth is that if you don’t trust someone to act honorably and help you change, then you probably shouldn’t invite that person to be a partner. However, if you don’t trust anyone to act honorably and help you change, then you should probably reexamine yourself and your ability to trust. That’s what John, The Talker, went through.

The Talker

I was embarrassed. It’s not like other people didn’t know that I talked a lot, but I was embarrassed to come out and say that I knew, too. I felt if I said it, it would be like saying that I knew I was a jerk or an annoyance or a blowhard. It would be like saying to everyone, “I know that you don’t really like spending time with me.” That just hurt. I really wanted to stay in my fake world where everyone pretended to ignore everyone else’s inadequacies and annoying quirks.

Besides, even if I could get past the embarrassment, this was a big career issue for me. I didn’t want to just come out and tell my colleagues that I had a “problem behavior.” That kind of information can come back to haunt you in a political organization like mine. I worked with a couple of people who were real snakes. They’d stab you in the back in a heartbeat.

There was one guy in particular who I really didn’t trust. I imagined what he would do if I talked to him about this. I envisioned elaborate scenarios in which he would use the information to prevent me from 70 getting promoted, to get my name taken off important committees, to stop me from getting other opportunities in the company. The more I thought about this guy, the more nervous I got.

Then it finally hit me and I knew what I was doing. I was using the worst case scenario to generalize about everyone I knew. My assessment of this guy may or may not have been accurate, but it certainly was not an accurate depiction of how my other colleagues would act. I knew a lot of people who cared about me and wanted to see me succeed. They were the partners I needed to seek. I allowed myself to get so wrapped up in my fears of what the snake would do that I failed to see the good things that others would be able to do.

John came to an important realization that there were people he could trust and people he couldn’t trust. His situation is similar to most. You probably know at least one or two people who are untrustworthy, can’t keep a secret, don’t care about you, and wouldn’t think twice about hurting you if it served their purposes. However, you probably know many more people who do care about you and who want to see you succeed.

Your challenge is to separate those who are trustworthy from those who are not. Once you do, you will find that trusting people and inviting them into your process creates benefits that are well worth the risks. Breaking your self-addiction is worth the vulnerability of sharing your development process. Developing a stronger relationship with the person because of this connection outweighs the discomfort and insecurity that it creates for you. You will also see that these are benefits that may come to your supporters as well.

I coached a woman who was trying to start a new exercise routine. When we began our work, she didn’t believe that anyone would simply want to help her. She thought that if she asked someone to help her, it would be a burden to them and they would resent her for asking. In fact, she thought these things because she was wrapped up in what this process meant to her. She never really considered what it could mean to someone else.

We weren’t talking about major commitments. All we were 71 discussing was asking one of her friends, a caring person who was something of an exercise buff, to ask her about her progress each week. They spoke on the phone regularly anyway. We were just considering dedicating a couple of minutes of those conversations to her workout progress, but she was dead set against it. Then I turned the tables.

I asked her what she would do if her friend asked her for help. What would she do if her friend asked her to do something that would take no more than five minutes each week, but would help him immensely? It was a no-brainer. Of course she would help. When I asked why, she had many reasons:

- She cared about her friend.

- It would make her feel good to be helpful.

- It might motivate her or give her insights for her own change.

- It was a minimal commitment for a powerful reward.

There are probably people in your life who aren’t trustworthy, but most people are. Not only are most people willing and able to help, but most will also receive benefits just from supporting your efforts. Alcoholics Anonymous figured this out with their sponsorship process. Far from being a burden, becoming a sponsor for someone else is actually a privilege that helps members complete the final steps of the process. By helping others, they actually help themselves.

Potential Supporters

Your goal in identifying partners is to identify as many people as you can who may be able to support your change. This is a brainstorming activity. Your objective is not to evaluate the names as they come to you. Rather, you want to identify as many names as you can. The longer your list, the more likely you will be to find partners who fit your needs. Include in your list your family members, friends, and colleagues who may be able to help you. 72

Exercise 4.1 Identify Possible Partners

Write down all the people you can think of who might be able to help you make your change. Take at least five minutes to identify these people.

Once you have completed your list, the next step will be to determine who on that list to ask for support, and what kind of partnership to form with each person. Remember that different people are right for different roles. It isn’t about the person so much as it is about your relationship to the person. I had an experience once in which I saw this contrast in a very personal way.

I met my wife in graduate school where she was studying for her PhD in psychology. A few years later I became good friends with another PhD candidate in a different program. My friend asked me if I could coach her to help her work toward the completion of her degree. I was thrilled to support this process and agreed readily. At the same time that I was coaching my friend, I saw my wife struggling with many of the same issues. Attaining a PhD is an extremely difficult task, and it pained me to watch her go through such a tough time. However, I was limited in how I could help her.

For my friend I could play many roles. I could push and challenge her and question her actions and decisions. I could give her advice and we could work together to develop action plans and strategies. For my wife I had to play a very different role. I couldn’t push or challenge her. She pushed herself so hard and put so much pressure on herself that she needed something else from me. She needed me to play more of a compassionate role. I had to be supportive of her at all times, but especially when she felt overwhelmed. The one thing I absolutely couldn’t do was pressure her the way I did my friend.

This is not a flaw in my relationship with my wife. It is simply an indication of how I could best help her achieve her goals. Sometimes people are too close to or too far from the issues for you to feel comfortable with them in certain roles. You may have a great role for your friend to play that you couldn’t possibly ask your mom to play. Your brother may be able to do something for you that your 73 coworker cannot. You need to recognize what you most need from each individual to get the best support out of the relationship.

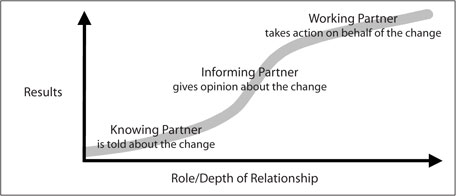

Supporting Roles

We will look at three different levels of support. Each has a certain depth to the relationship, and the deeper that relationship is, the more power it has to affect your change. These three types of partners are illustrated in the graph below.

The Knowing Partner

A knowing partner is simply anyone who knows what change you are trying to make. You tell them about your change. They know what you are trying to do, but they don’t have any defined role in the process. If they do something, it is by their own design. A knowing partner can be anyone—friends, family, coworkers, your cab driver, or the checkout person at the supermarket. They merely need to hear your statement to play their role. Of course, the closer to you they are, the more their knowing is likely to influence your behavior. Having knowing partners can certainly help, but they are the weakest social support that you can create. 74

The Informing Partner

Informing partners give you their opinions about your change. These supporters are ones whom you tell about your efforts and ask to give you feedback on your performance. For these to be truly effective, you should make plans to speak with them regularly about your progress. Frequently, people create informing partners by saying something like, “I’m trying to be less defensive. I’d like you to let me know how I’m doing.” Then they walk away and never discuss the matter again. It’s much more effective when the individual says, “I’m trying to be less defensive. I’d like to meet with you once a week to hear your observations on how I am doing.” An informing partner should be someone who can observe you in action. It does little good for you to ask for feedback on your behavior from someone who rarely or never sees you exhibit the behavior in question.

If you are willing to consistently ask for feedback, you will do a much better job of accomplishing your goals. Consistent feedback is not the same as extensive feedback. In fact, you can ask for this information in very brief conversations of only a few minutes duration. The key is to conduct these conversations consistently.

The Working Partner

Working partners are people who actually take action on your behalf to help you make the change. They may stop you when they see you engaging in the addictive behavior, as the friend I described at the beginning of this chapter did for me. Working partners can also be those who help you think through your actions and develop strategies for building new behaviors. If you have talked through any of the exercises in this book with someone else, that person was acting as a working partner. A working partner can also be someone who is going through the same change effort as you. For example, someone who goes with you to the gym to exercise can be a working partner.

A working partner can do a lot of things to help you succeed, but there is one thing that makes this partnership particularly valuable. The working partner will share the burden of the change with 75 you. Making meaningful and lasting change is a challenging and prolonged process and you are bound to face setbacks along the way. Working partners help you to keep going, to get past the difficult times, and to achieve your goals.

Here are four different types of working partners:

Thinker—someone who will help you think through plans and strategies for your change.

Challenger—someone who will push you to higher levels of achievement.

Supporter—someone who will provide you with positive feedback and encouragement.

Actor—someone who is with you and will act to help you alter your self-addictive behavior the moment you engage in it.

Each of the above roles can be distinct from one another, or someone could play multiple roles. Following are some of the roles I asked people to play in helping me to write this book.

These weren’t all of the partners involved in the process, but they are good examples of people who played tremendous roles in helping me develop the writing behaviors and discipline that made this book possible. In the next exercise you will review your list of names of possible supporters and determine the roles each person can play. 76

Exercise 4.2 Create Roles

Go through your list of possible partners and create roles that each one could play. Try to identify at least two people as informing partners and at least two as working partners. You do not have to assign a role to everyone on your list of possible partners. In fact, if there are people on your list whom you do not trust, now is the time to remove them from the process.

Don’t ask them for this support yet. The next chapter will provide strategies for creating an effective support relationship.

Addiction Enablers

You have now started to build your own Circle of Support. The next chapter will detail how to approach your partners and develop effective relationships to support your change. However, there is a flip side to the support coin. As you have examined the people in your life who may be able to help you make your change, you may also have come across people who will make it difficult for you to change. There will inevitably be people who make it easy for you, even encourage you, to engage in your self-addictions. These people are addiction enablers, and they come in many forms.

- The Coconspirator does it with you. These are the people who take a break with you to go smoke a cigarette. These could be people who are always willing to join in when you want to be angry, bitter, and negative. Coconspirators share your self-addiction and make it easier for you to maintain the behavior.

- The Pessimist believes that you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. They just don’t think people change. Pessimists make it easy for you to choose not to do anything about your self-addiction because they convince you that it would all be a wasted effort anyway.

- The Admirer tells you that whatever you’re doing isn’t so bad. They may say, “Don’t get so down on yourself. You’re a great person.” Admirers are incapable of saying anything critical. They love to compliment you and make you feel 77 great about yourself, even if that stops you from making improvements in your life.

- The Avoider turns the other cheek and pretends that the behavior doesn’t exist. They may get angry or frustrated with you on the inside, but they won’t let you know.

Each of these addiction enablers makes it difficult for you to break your self-addictions, but that doesn’t make them bad people. In fact, in their own ways they may be trying to help. It’s just that they don’t realize how their actions actually hurt you. They simply don’t know that they have the opposite effect from what you desire. The good news is, they are likely more than happy to do something differently so they can help you. You just need to tell them about it. When I was a smoker I had lots of coconspirators who would actively encourage me to join them for a cigarette or to buy in bulk to reduce the cost. When I told them that I was quitting, they turned their behavior around and refused to let me have any of their cigarettes if I asked. They went from coconspirators to working partners.

In some cases, you will be able to easily change the behaviors of your addiction enablers. In others, their behaviors will be too entrenched to change, and your challenge will be to negate their messages. There are three ways in which you can limit or eliminate the impact of your addiction enablers. First, you can avoid them. The simplest solution (assuming the addiction enabler isn’t someone important to you) is simply to reduce your exposure to them.

Second, you can try to change them. You can ask them to change their behaviors and help you make your change. This can be a good strategy, but you will need to watch to make sure they are playing the role you want them to play and not sliding back into enabling your addictions.

Third, you can change the way you respond to their behavior. If you know what kind of addiction enabler they are, you can adjust your response based on that knowledge. With the Pessimist, the Admirer, and the Avoider, you will need to remind yourself that they don’t own the truth. When you speak with them, it is important to avoid getting sucked into their version of reality. You 78 need to remember that change is more possible than what the Pessimist says. Your behavior is more important than what the Admirer tells you. The Avoider is more affected by your behavior than she lets on. If you prepare yourself with this knowledge, then you can construct your own version of the truth to fuel your efforts.

The Coconspirators are different in that they push you into your addictive behaviors in the moment. They offer you a donut when you’re on a diet. They invite you to join them in their misery when you are trying to be more optimistic and positive. With the Coconspirators you can begin with this strategy: just say “no.” In Steps 7 and 8 we will discuss at greater length different strategies for preparing yourself to avoid your addictive behaviors and achieve new, more positive behaviors. For now, here is an example of how someone trying to break the addiction to a short temper dealt with her addiction enablers.

79 The next exercise will help you to identify the addiction enablers in your life. Then you will think through strategies for addressing each of them.

Exercise 4.3 Disable Your Addiction Enablers

Construct a chart like the one on page 78. Identify people who play each enabler role in your life (Coconspirator, Pessimist, Admirer, Avoider). Keep in mind that some of the roles may be played by multiple people, some people may play multiple roles, and some roles may not be played by anyone.Then come up with at least one strategy for each of the addiction enablers you have identified.

Surrounding With Support

You should now have a clear picture of the people who surround you. You should know which of them can open up new possibilities for helping you to change. You should also see who around you might cause you to slip back into bad behaviors. Understanding the players is the first step. The next step will be approaching each of these individuals, asking for their support, and coaching them in how they can best help you make your change. That is the topic of Step 5, Invite Support.