ADAPTIVE

Be Fast

Tata Consultancy Services: Adapting to Grow

Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), the largest Indian company by market cap as of 2014, has grown into one of the most successful technology services firms by evolving rapidly in response to waves of technological change through an ongoing stream of small business-model innovations.1 This adaptive approach enabled TCS to grow from a small player to a leading global one. TCS’s revenue growth is impressive: $20 million in 1991, $155 million in 1996, $1 billion in 2003, and more than $13 billion in 2014. From establishing India’s first dedicated software R&D center in 1981 to developing India’s first offshore development center in 1985 to entering the bioinformatics market in 2005 and then cloud computing in 2011, TCS has continually evolved by responding to changes in the technology environment and the changes’ impact on corporate customers.2

TCS, while large, is just one of many firms competing in the fragmented space of technology services, an area that includes software solutions and services, consulting, engineering services, and business process outsourcing. Most players in this area have just single-digit market shares, so no firm can definitively shape the direction of the market, and rapid technological change makes for a high level of unpredictability.

In spite of its size, TCS is very externally oriented so that it can capture and harness change. The firm has grown with the environment, as the world economy has shifted from a physical to a digital economy.

With over two decades at TCS before he became CEO in 2009, Natarajan “Chandra” Chandrasekaran has overseen many of the evolutions in its service offering. “From an IT architecture point of view,” Chandra told us, “we started during the mainframe environment and have, over the years, adapted to a client-server environment, after which came the internet environment and today’s digital or hyperconnected environment.” Chandra sees digital technologies fundamentally affecting companies in many, often unpredictable ways: “Every business process will get reimagined. Every business model will get reimagined. How the company works internally will get reimagined. It is our job to engage with customers on how they think about digital . . . and we will shape our delivery model accordingly.” TCS therefore has to doubly adapt to both changing technologies and changing customer usage environments.

As technology and customer needs change, TCS has responded quickly and appropriately. For instance, the firm recognized early client demand for a business division devoted to proliferating online channels.

This need to adapt requires an external orientation that cascades throughout the organization, from strategizing to organization to innovation. For instance, in setting direction, TCS balances a rough top-down approach with bottom-up challenge, whereby a central group provides critical market information on each industry vertical—industry size; growth; and competition, technology, and demand trends—then challenges each business to come up with its own approach to best meet specific customer needs. This way, the eventual strategic direction emerges from a collection of individual initiatives that address the specific environmental changes and other new situations that each business segment faces.

Because the future can’t be planned, Chandra does not take a classical portfolio-management approach: “We don’t want to have [segment-level] cash cows or stars . . . This is about creating opportunities for each business to evolve and grow.” TCS places many small bets and then, depending on the success of each initiative, can reallocate resources quickly across businesses. The approach to innovation is experimental and rapid: TCS runs rapid cycles of what it calls the 4E Model—explore, enable, evangelize, and exploit. The model focuses on proactively promoting research across diverse areas, building prototypes, testing, launching, and scaling up.3 Because vast troves of information from disparate sources are critical for varied, rich exploration, TCS has invested heavily in its analytic capabilities to support these efforts.

Chandra told us that “customer-centricity” is the most important part of TCS’s innovation model: “Understanding and often preempting what the customer needs . . . is at the core of our strategic innovation, helping us innovate in our business solutions, delivery, and service models.” Several innovations have paid off for TCS. For example, the MasterCraft suite of tools leverages TCS’s expertise in the automation of the software development process to deliver quicker and higher-quality client support. And the Just Ask product, a social Q&A platform that enables a client to tap into the client’s own tacit individual or crowd knowledge, enables greater collaboration and reduction of time to market.

In addition to innovating in its products and services, TCS embeds innovation at two other levels in the business. At the engagement level, leadership encourages each business unit to think of every engagement as an opportunity for innovation, since each IT services project has unique characteristics. Finally, Chandra fosters an innovation-oriented, experimental mind-set at the individual employee level. He explained: “With three hundred thousand employees, we have tremendous intellectual horsepower within the company.” For instance, the firm’s Realize Your Potential program runs contests and hackathons around specific issues faced by customers or by some of the Tata group companies; any employee can participate in these events.4

TCS has achieved the rare feat of being both large and nimble by building a modular organization that is empowered to experiment. Since Chandra took over in 2009, the firm has grown from 140,000 employees to twice that.5 He said: “The company is very large, but we cannot get rigid, so we created twenty-three units, each addressing a specific group of clients. [The units] have common elements and, at the same time, are able to run with their own strategy. We don’t want hierarchy; we want network.” TCS’s attempts to reimagine how the firm works and collaborates include the Vivacious Enterprise, a social collaboration platform aimed at fostering engagement across TCS’s large and distributed workforce.6 Scale certainly helps TCS—it operates in almost fifty countries, is able to collaborate credibly with large global clients, and is the second-largest pure IT firm after IBM.7 But unlike a classical firm, TCS doesn’t win because it is big; it is big because it wins by taking an adaptive approach.

The Adaptive Approach to Strategy: Core Idea

When the business environment is unpredictable and nonmalleable and advantage may be short-lived, firms have to be ready to adapt quickly to succeed. As Chandra realized in the incessantly shifting technology services industry, an adaptive approach can drive growth and advantage by continuously adjusting to new opportunities and conditions (figure 3-1).

Like the classical approach, the adaptive approach has its own characteristic thought flow. Adaptive firms continuously vary how they do business by generating novel options, selecting the most promising, which they then scale up and exploit before repeating the cycle.

In terms of our art metaphor, the adaptive approach is like painting a landscape under changing light conditions. You need to keep your eye on your subject, work fast, and repeatedly layer brush stroke upon brush stroke until you have captured the fleeting moment—and then move on to capturing the next scene.

Strategy emerges from the continuous repetition of this vary, select, scale up thought flow, rather than from analysis, prediction, and top-down mandate. By iterating more rapidly and effectively than rivals do, adaptive firms outperform others, but the classical notion of sustainable competitive advantage is replaced by the idea of serial temporary advantage. As Rupert Murdoch, the chairman of News Corporation, noted: “The world is changing very fast. Big will not beat small anymore. It will be the fast beating the slow.”8

An adaptive approach is therefore fundamentally different from the classical one: it does not center on a plan, there is no one “strategy,” the emphasis is on experimentation rather than analysis and planning, advantage is temporary, and the focus is on means, not ends. We will explore some of these differences and their implications in the following sections, but first let’s look at another example of adaptive strategy in action.

Why Speed and Learning Matter: Zara

Zara, the Spanish fashion retailer, is a prime example of a company that has become very adaptable in an extremely unpredictable industry.9 On the eve of a new season, fashion retailers can hardly predict whether black is the new black or whether some other color is. In fact, even within a season, customer tastes frequently change. Historically, however, most retailers effectively relied on predictions of what customers would want to wear. And most retailers usually got it wrong and suffered the consequences, having to discount as much as half their stock each year.

Inditex, the holding company of Zara, was no longer happy to bear these kinds of costs and decided to take an adaptive approach to manufacturing and retailing. The holding company introduced fast fashion, in industry parlance, with Zara’s launch in 1975. Instead of trying to predict what customers might want, Zara opted to react faster to what they actually buy.

Zara achieved this in two ways. First, it shortened its supply chain, moving production facilities closer to customers and willingly accepting the trade-off of slightly higher manufacturing costs to gain more agility. Among other measures, the firm relocated production facilities for United States and European markets from East Asia to countries closer to end markets—countries like Mexico, Turkey, and North Africa. Proximity sourcing has been a success factor for Inditex’s model since its origination. The shortened supply chain reduced the time it took to deliver products from the design studio to the main street store to a mere three weeks—an extraordinary five months less than the industry average.10

Second, Zara produces only small batches of each style. In effect, these are real-time, in-market experiments, and the successful styles, those that flew off the racks, were selected for scaling up. The retailer tests many more items than its rivals, thereby keeping its customers engaged and ready for more. In fact, Zara commits six months in advance to only 15 to 25 percent of a season’s line and locks in only 50 to 60 percent by the start of the season, versus an 80 percent industry average. Consequently, up to 50 percent of Zara’s clothes are designed and manufactured right in the middle of the season.11 If harem pants and leather are suddenly the rage, Zara reacts quickly, designs new styles, and gets them into stores before the trend has peaked or passed.

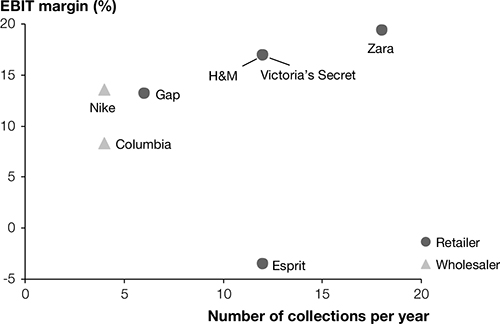

The impact has been significant: in 2010, Zara marked down only 15 to 20 percent of its inventory, in contrast to the industry average of 50 percent.12 Also, even though its direct production costs are higher than those of competitors that mostly center production in the Far East, Zara’s profit margins in that period were consistently double the average for the industry, and the retailer achieved significantly higher inventory turns to boost its return on capital (figure 3-2).

Zara’s adaptive approach in the fashion industry generates high returns

Source: Capital IQ, BCG estimates; BCG project experience; company annual reports.

Note: EBIT, earnings before interest and taxes.

WHAT YOU MIGHT KNOW IT AS

The advantage of adaptability is not a new notion. Charles Darwin first recognized the power of evolutionary processes, or adaptation, in the biological world. And adaptive business approaches—the notion that strategy cannot always be planned and that speed and flexibility can produce competitive advantage—owe a huge debt to biological thinking.

In the late 1970s, Henry Mintzberg argued that companies sometimes unintentionally end up capitalizing on emergent strategies. These strategies are not the result of deliberate top-down plans, but rather emerge serendipitously while the intended plan is being pursued.13

In the 1980s, Richard Nelson and Sidney Winter developed the theory of evolutionary economics, suggesting that economic progress is essentially adaptive. BCG leaders Tom Hout and George Stalk around this time pioneered the concept of time-based competition, which held that advantage could be created by reducing cycle times in processes like new product development and production. Time-based competition centered on executing existing tasks faster, whereas adaptation also requires firms to learn how to do new things faster and more effectively too.14

In the late 1990s, Charles Fine developed the notion of temporary advantage, arguing that advantage is increasingly short-lived and that firms need to match their strategy cycle to the industry’s “clock speed.” Around the same time, Kathleen Eisenhardt argued that under high uncertainty, organizations and strategies can become agile by using simple rules that serve as guidelines and principles in place of complex rules and instructions. Rita McGrath also pioneered the idea of discovery-based planning, where plans are not treated as output forecasts against which performance is assessed but rather as plans for discovery that maximize learning while minimizing cost.15

Finally, BCG developed and commercialized the adaptive advantage concept in the early 2010s to help its clients react to increasing change and uncertainty. This concept detailed how firms can practically realize bottom-up strategic experimentation to replace top-down planning.16

When to Apply an Adaptive Approach

An adaptive approach to strategy is appropriate when—and only when—your company is operating in an environment that is both hard to predict and hard to shape.

So how can you recognize an adaptive environment? Essentially, an adaptive strategy is called for when forecasts are no longer reliable enough to produce accurate and durable plans because of ongoing, substantial change in technologies, customer needs, competitive offerings, or industry structure. Such an environment manifests itself in volatile demand, competitive rankings, and earnings; large forecasting errors; and short forecasting horizons.

By these measures, turbulence and uncertainty are now strikingly more frequent and intense in many industries and persist for longer than in previous periods (figure 3-3). Until the 1980s, less than a third of business sectors regularly experienced turbulence. But because of globalization, accelerated technological innovation, deregulation, and other forces, roughly two-thirds of the sectors now do.17

Increasing unpredictability of returns

Source: Compustat, BCG analysis.

Note: Volatility based on all public US companies.

*Average five-year rolling standard deviation of percent firm market capitalization growth by sector, weighted by firm market capitalization.

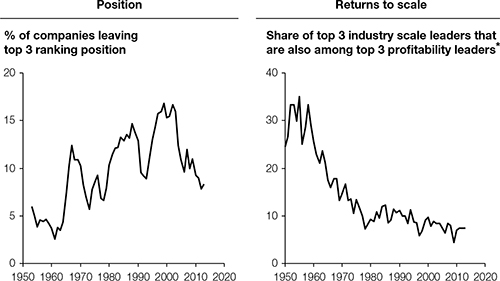

Over the past thirty years, the turbulence of business operating margins, largely static since the 1950s, has more than doubled. Also, the percentage of companies falling out of the top three revenue rankings in their industry each year rose from 3 percent in 1961 to 17 percent in 2002 and was around 8 percent in 2013. The value of incumbency has also diminished: the probability that the top three market-share leaders are also among the top three profitability leaders declined from 35 percent in 1955 to just 7 percent in 2013 (figure 3-4).

Some industries have been especially hard hit by the turbulence; they include software, internet retailing, semiconductors, and, as we saw with Zara, the fashion industry. Most companies in these sectors should be contemplating an adaptive approach to strategy—for part, if not all, of their business.

Sources of traditional competitive advantage are eroding

Source: BCG Strategy Institute analysis, September 2014, Compustat.

Note: Cross-industry analysis based on thirty-four thousand companies in seventy industries: unweighted average. Industries excluded in years where less than six ranks; companies were excluded in years where only sales or earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) were reported, or if sales were less than $50 million, or whose margins were less than –300% or greater than 100%.

*Scale is calculated as net sales, profitability as EBIT margin (on net sales).

Indeed, such is the prevalence of turbulence today that even some companies from capital-intensive industries more typically associated with a classical approach might also need to consider deploying an adaptive one. Take mining and metals, for instance. The volatility of metals and minerals prices from 2000 to 2010 was more than six times that of the previous decade.18 Most mining and metals firms find it hard to make their operations flexible and adaptive because of the long cycle, large-scale capital investments involved. Nevertheless, they are increasingly compelled to find new ways to increase flexibility because even moderate volatility in prices or demand against a high-fixed-cost base can wreak havoc with earnings. As a result, several firms in that sector are trying to shorten their capital cycles, spread investments over an increasing number of smaller assets, share ownership risk, make their operations more flexible, and exploit uncertainty by establishing asset-backed trading arms. As Jac Nasser, CEO of BHP Billiton, said in September 2013: “All resources companies will need to improve productivity and be flexible enough to adapt to change in this more challenging market.”19

Accurately assessing the environment is therefore critical. But it is clear from our research that many companies that objectively face an adaptive environment fail to perceive it as such, because they tend to overestimate the degree to which they can predict or control it. Conversely, even though turbulence is on the rise overall, the adaptive approach is not a panacea and must be applied selectively, when appropriate. As we saw in chapter 2, for many situations, a classical approach is still the right one.

ARE YOU IN AN ADAPTIVE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT?

You are facing an adaptive business situation if the following observations hold true:

![]() Your industry is dynamic.

Your industry is dynamic.

![]() Your industry’s development is unpredictable.

Your industry’s development is unpredictable.

![]() Your industry is not easily shapable.

Your industry is not easily shapable.

![]() Your industry displays high growth.

Your industry displays high growth.

![]() Your industry’s structure is fragmented.

Your industry’s structure is fragmented.

![]() Your industry is immature.

Your industry is immature.

![]() Your industry is based on changing technologies.

Your industry is based on changing technologies.

![]() Your industry is subject to changing regulation.

Your industry is subject to changing regulation.

The Adaptive Approach in Practice: Strategizing

Because adaptive strategy emerges continuously from iterative experimentation that is deeply embedded in the organization, thinking and doing converge. The simultaneous nature of these two activities differs from the classical approach, which is composed of two sequential phases of (1) analysis and planning and (2) execution. These activities are performed by different parts of the organization. In the adaptive approach, such a separation between strategizing and implementation would be fatal, slowing down and blunting the learning process. In this chapter therefore, the section on strategizing covers the entire process from capturing change signals to managing a portfolio of experiments. The implementation section of this chapter then deals with the broader organizational context that supports and enables this process to take place.

Applying an adaptive approach is easier said than done. Leaders increasingly use the vocabulary of adaptation, referring to VUCA environments (those with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) and extolling the virtues of agility and adaptability.20 However, as we will see later, many of these same firms continue to cling onto the top-down, slow-cycle, planning-centered practices associated with the classical approach.

The adaptive approach involves reading and digesting change signals to manage a portfolio of experiments focused on areas of highest opportunity or vulnerability. The goal is to run the cycle of vary, select, and scale up more quickly, economically, and effectively than rivals do, to build and renew temporary advantage.

Unlike classical strategy, adaptive strategy does not have predefined ends, because these are unknowable in an unpredictable environment. Strategy emerges and evolves iteratively. Leaders using an adaptive approach would therefore be missing the point by talking about the strategy. Leadership can define a domain of focus, a rough direction, or an aspiration, but the specific strategies are emergent and dynamic. In contrast, the approach to experimentation can be very deliberate. The risk taking and creativity required by an adaptive strategy may look undisciplined compared with a classical approach. But adaptive strategy requires an equal level but different sort of discipline throughout—from generating new options, to determining how promising ones are tested and selected, to establishing how to reallocate resources from less promising projects toward those that show potential.

Reading Change Signals

As Niels Bohr, the Danish Nobel Prize–winning physicist once put it: “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” So what should a firm do when it cannot set its direction through prediction?

To react to and harness change, firms need first to observe and to try to make sense of it. When observing change, firms need to capture the right information and decode it to discriminate between trivial and significant changes (the latter changes being those that might be threatening or constitute opportunities) and between forecastable, knowable factors and currently unknowable ones that require exploration and experimentation. To understand the significance of change, firms need also to question and challenge what they think they know by uncovering and reconsidering blind spots and hidden assumptions. External change signals might therefore point directly at an opportunity or a threat or more indirectly at an area of uncertainty where the firm needs to gather more information through experimentation. In this way, experimentation need not be blind, but rather can be more of a guided learning process.21

Capturing the right data can be immensely valuable to continuously generate new insights about changes in demand or competition. In Japan, global grocery chain 7-Eleven gained a significant information advantage in the early 2000s by leveraging its point-of-sale systems to track not just sales, but also other variables, such as customer demographics and even the weather and time of the day. With this data, the firm could test hypotheses about how these variables drive sales in real time, allowing 7-Eleven to identify promising or less promising items in a particular context. Thus, pricing, assortment, promotions, and layout could be optimized to local conditions on a daily or even multi-hourly basis by location. For example, the 7-Eleven systems could track the altered demand for lunch boxes from a new nearby building site and rapidly adjust the assortment on a store-by-store basis.22

Often the relevant information is already available and right under a company’s nose, originating, for instance, from interactions with consumers, suppliers, and other stakeholders, but the information may need to be properly captured and decoded through the use of data mining and analytics. Firms must be able to decode hidden patterns in large data sets and to react to changes rapidly before someone else does. The days when companies could secure an advantage by merely possessing information are dwindling: the information they possess may quickly lose relevance or may harbor hidden patterns that need to be teased out.

To understand the significance of change, firms must foster self-awareness about what they really know and must uncover their own hidden assumptions. This information map can shift constantly in a changing environment. In some cases, firms underleverage new information available to them—what we might call underexploited knowns, or elephants. There is also much that you may erroneously think you know—false knowns, or unicorns—and may need to challenge. Most challengingly, some things cannot be known at the time, without a change of perspective or further experimentation—double question marks, or unknown unknowns, to borrow an expression from Donald Rumsfeld, the former US secretary of defense (figure 3-5).23

Understandably, large companies find it hard to identify and address these three types of blind spots, since most operate with a classically biased world view. Firms assume they have a high level of knowledge about the market or competitive landscape and expect to see only a modest degree of change.

The story of big US car manufacturers and hybrid cars offers a lesson on underexploited knowns. In the early 1990s, the Clinton administration challenged the big automakers to design cars that were more fuel-efficient, against the backdrop of a growing ecological awareness among consumers. GM, Ford, and Chrysler did develop prototypes—but few reached the production line.24 This left a gap for Toyota. Its Prius became the first mass-produced hybrid car and was extremely successful. Cumulatively, Prius passed the one million vehicles sold mark in 2008 and reached three million in 2013. In 2009, it was the best-selling car in Japan.25

In other cases, firms may neglect to challenge a false known, a dominant but increasingly obsolete world view, in spite of abundant signals of change, because they underrate or ignore information at their disposal. An example of a false known is the apparently reasonable assumption that to at least some significant degree, people use smartphones for making phone calls! It is easy to imagine both how challenging it is for a long-standing telecommunications provider to question this belief and the significant strategic consequences of doing so. Telenor, a Norwegian telecom company, in fact did question this belief, as we will explore later in this chapter.

Of course, there are always things that a company may not or simply can’t know—unknown unknowns—without experimenting or a changing its vantage point. Therefore, adaptive companies need to build a culture of self-challenge, one that encourages the questioning of a company’s dominant logic to uncover and employs techniques aimed at highlighting blind spots. For instance, they try to look at their own firm through the eyes of an imaginary or real enemy, engage in war gaming against their own business model, or try to make an opposing business case or mandate a compulsory dissenting opinion for each new investment recommendation, in order to deliberately expand their field of vision.

Managing a Portfolio of Experiments

In a turbulent business environment, a company’s products, services, and business models can become obsolete very quickly. At the same time, firms cannot predict which new elements will replace the old ones. Luckily, leaders have a viable alternative to prediction: running a portfolio of strategic experiments managed with an eye on the twin imperatives of speed and economy. To do so successfully, firms set the perimeter for experimentation by reading change signals and generating a sufficient volume of new ideas to test in areas of interest. Promising opportunities emerge quickly through disciplined experimentation, with clear rules for selecting and pushing projects forward. Finally, firms scale up successful experiments by rapidly and cleanly reallocating resources.

Companies should first decide what to test. They should leverage change signals to focus on the areas that suggest the highest growth potential, the biggest threats, or the most important blind spots. Even where you lack a clear hypothesis, more experimentation yields more information, which yields more options. Unlike the classical firm, the adaptive firm leans toward taking action first rather than analysis.

Adaptive firms tap into two sources to make sure that they have sufficiently large numbers of new ideas to test. Either they embrace the natural variance inherent in the way the company operates, or they proactively introduce variance by creating a range of experiments and testing them. Passive works well in activities like trading or selling, where there is significant natural variance to tap into. Variance gives the adaptive firm a wide option set to explore. Interestingly, it is precisely this variance that classical firms try to eliminate from their processes in the pursuit of ever-higher efficiency levels. For this reason, it can be extremely difficult for a classical firm to really embrace an experimental approach even when such an approach becomes acutely necessary.

Google is not yet twenty years old and operates in a ferociously unpredictable market. Its cofounder and CEO Larry Page couldn’t make the point more strongly: “Many leaders of big organizations, I think, don’t believe that change is possible. But if you look at history, things do change; and if your business is static, you’re likely to have issues.”26 As a consequence, Google experiments on a wide range of options close to and distant from its core business—from AdWords to more exploratory investments through Google Ventures or speculative projects such as Google Glass. Many of these ideas come from the much celebrated 20 percent time program, which lets some employees spend as much as 20 percent of their time working freely on new projects of their choice.27

To ensure that experiments function quickly and cheaply, firms need clear rules for framing, executing, and assessing experiments, applying a principle of freedom within a disciplined framework. On a portfolio level, adaptive firms should strictly monitor their economics of experimentation. They should measure and optimize the number of experiments, the costs, the success rates, and the speed of progression. Typically, experiments should be individually small, large in overall number, and quick to come to a conclusion. Rather than investing a lot of time to evaluate and attempt to predict the success of each project before it is launched, adaptive firms continuously validate what is working in practice and iterate frequently on their portfolio. As management writer Tom Peters has urged: “Test fast, fail fast, adjust fast.”28

To return to Google: the firm actively measures experimentation outcomes so that, in light of the results, Google can rapidly reallocate resources among projects. Over the past ten years, Google has both launched and killed roughly ten to fifteen products annually without major customer or organizational resentment.29 While a classical strategist could think that the adaptive strategy sounds like “try something and see what sticks,” objective data—rather than disputable gut feel—governs each decision.

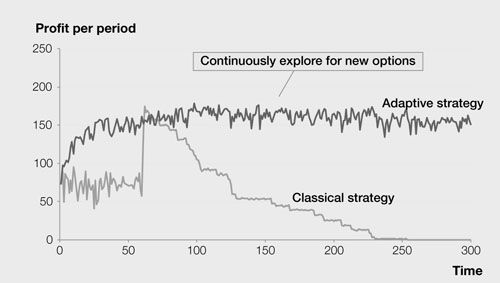

Classical strategies perform well when an environment is stable, because the attractiveness of the option chosen after careful analysis doesn’t change. However, when we add environmental dynamism and uncertainty to our computer simulation, classical strategies underperform strategies that invest more in continuously exploring new options.

In an uncertain environment, it is likely that the rewards from a currently exploited option will decrease or that new, potentially better options will arise. Therefore, strategies that continuously invest a proportion of resources in exploring new options, or adaptation, should yield improved performance.

Our simulation confirms this relationship. Increasing the degree of uncertainty of rewards per option over time requires a proportionally higher degree and continuity of investment in exploration (figure 3-6).

The telecom industry is a prime example of an industry whose environment has undergone a rapid shift from a relatively stable classical environment to a more rapidly shifting adaptive one. Jon Fredrik Baksaas, CEO of the Norwegian telecom operator Telenor, described the change through analogy: “I call it the ‘concrete phenomenon.’ You used to be able to plan: how many houses will be built, how much cement will you need, and you produced that much. And then you did it for the next year. And that is fundamentally different today. In our traditional fixed-line business, we have that degree of certainty, to some extent, but that’s where it stops.”30

Telenor’s advantage in the historically stable telecom industry came from its scale and cost competitiveness in operating fixed-line and mobile-phone network businesses in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. However, in the late 2000s, Telenor faced new challenges with the maturation of its network businesses, the accelerating switch in revenue contribution from voice to data, and the flurry of new internet-based services introduced by both tech giants and start-ups like Netflix and WhatsApp. In a short period of time, competition became more fragmented, consumer preferences and segmentation changed, and the industry became much less predictable.31

Telenor has succeeded, locally and in emerging markets, by implementing an adaptive approach to strategy, especially in the new areas of its businesses. For instance, it adjusted the speed and horizon of its planning to be more iterative, with a focus on seeing what’s happening and responding quickly, and added quarterly updates and revisions to the plan. “Minimizing delays in getting products to market is more important than hitting pre-set targets,” Baksaas said.

Additionally, Telenor has adjusted its approach to innovation. Baksaas gave us an example of why speed to market and novelty are so important: “I was speaking to an audience and asked how many had smartphones—ninety percent raised their hands. How many had iPhones? Seventy percent. And of those, how many had used the phone that morning to make a voice call? Only five percent. Everyone else had used their phone, but they had been using data and apps. So we must adapt our model accordingly.” In practice, that means that Telenor protects and funds innovation through a trial-and-error process in the innovation’s early stages before integrating it into the broader business. Telenor closely manages its experimentation engine, paying attention to adaptive metrics like cost per experiment, time to market, and percentage of sales from new products. It then scales up successfully piloted products rapidly, like appear.in, an in-browser group video conversation service. After a test-and-learn period, the appear.in service is now fully global, serving customers in 175 countries.32

Telenor has also updated its approach to talent management to “nurture and appreciate the risk-takers and innovators.” The firm, for example, developed a forty-person global leadership program that draws from across the organization and works to generate new business ideas; from this diverse, cross-functional group, eight novel ideas are in the development phase.

Baksaas emphasized that “in an era of unpredictability, the incumbent has the most to lose.” To combat the natural inertia that comes from comfortable positions of monopoly or scale, Telenor systematically leverages learning and experience from business in areas where the rate of change is the quickest, like Asian markets. There Telenor focuses on reaching and connecting the most consumers the fastest, for example, by driving the development of mobile phones placed at a price point below $20.

The Adaptive Approach in Practice: Implementation

Let’s look at the broader organizational context that supports and reinforces the adaptive approach to strategy. The approach must be embedded in every aspect of the organization, with an eye to promoting signal capture, experimentation, and selection by promoting external orientation, bottom-up initiative, and an agile and flexible organization.

Information

As we’ve seen, information management is critical for both signal capture and effective management of a portfolio of experiments. Therefore, adaptive firms must continuously refresh their data on external change and must have the analytic capabilities to uncover hidden patterns. These functions and capabilities need to be broadly embedded in the organization. To manage experimentation, information is needed on two levels: information to manage individual experiments (i.e., data on outcomes and controls for each experiment) and information to manage the overall portfolio (such as overall success rate, costs, speed, and aggregate return on investment).

Since the firm that first deciphers and acts on change signals gains advantage in an adaptive environment, the firm’s intelligence about the industry, the competition, and customer and consumer trends must be excellent. Adaptive firms, therefore, must invest in developing advanced analytics capabilities that can capture and leverage disparate, real-time data. Since the precise applications of patterns cannot be foreseen, the information needs to be easily and broadly accessible and visualized in a way that makes it easy for all parts of the organization to tap into it.

Car insurance company Progressive is a good example of a firm that built competitive advantage by using novel real-time signals to understand risk in a very segmented fashion. In the late 1990s, Progressive became the first US insurer to build capabilities in telematics, a technology that reads and reports data in real time from remote objects. In 2011, the firm introduced Snapshot, a small telematic device that drivers place in their cars. The device reports data on driver behavior such as mileage and acceleration and braking patterns. With that information, Progressive can create an individualized dynamic risk profile and offer savings of up to 30 percent to low-risk customers.33 Additionally, the firm uses the knowledge gained to continuously refine and update its customer and product segmentation. As a result of this, Progressive has improved on all major dimensions—sales volumes, retention, and loss ratio on its customer base. Progressive’s CEO, Glenn Renwick, said, “I consider Snapshot to be one of the most important things I’ve personally seen in my career.”34

Good results require accurate data for both the experiment and the corresponding control to determine whether the outcome meets the criteria for advancing or stopping the experiment. Effective experimentation also requires monitoring and management of overall idea generation, success rates, experimentation costs, speed of progression and resource allocation across the portfolio to maximize the yield on experimentation.

The firm needs to extract as much learning as possible from each of its experiments—including those that don’t work. Failures are critical for adaptive firms, since these experiments could contain valuable information not only on what specifically works and what doesn’t, but also on the effectiveness of the experimental approach itself. Caesars Entertainment, a casino operator, leverages the information from the dozens of experiments it conducts in parallel not only to identify the best products for its customers, but also to fine-tune the experimentation process itself. Experiments are undertaken in separate, controlled parts of a casino so that each test can be properly assessed and, if appropriate, rolled out across the company.35 It is a rigorous process. As Gary Loveman, the CEO, joked: “There are two ways to get fired from Caesars: stealing from the company or failing to include a proper control group in your business experiment.”36

Innovation

Continuous innovation is quite obviously the lifeblood of an adaptive organization. Since adaptive companies experiment without a predefined goal, they need a disciplined and iterative innovation process to ensure that the best initiatives surface fast and economically. Therefore, adaptive innovation needs to be informed by external signals, built on small, low-cost bets, and iterated upon frequently. And, on a higher level, the process needs to be tolerant of failure and managed for overall economic optimality. This is certainly not to say that innovation and novelty are maximized for their own sake: experimentation is expensive and risky. So the adaptive firm also needs to adjust its rate of exploration to the circumstances and clock speed of its environment and then makes sure that the firm also fully exploits its successes, albeit for short periods.

We dealt with many of the key features of adaptive innovation in this chapter’s section on strategizing, so let’s now look at some essential differences with how innovation is normally conceived and implemented. Innovation in a classical firm is often somewhat detached from regular business activities, consisting of occasional leaps driven by an entirely separate R&D department. In an adaptive approach, innovation is the opposite: small steps, continuous, and operationally embedded. And unlike the visionary or classical approaches, you may not initially know what “new” thing you’re looking for, so you will inevitably have failures, setbacks, and surprises. Therefore, adaptive firms manage individual projects for speed, incentivizing progression and enforcing short timelines to push teams to converge quickly on whether something is worth progressing further, requires a change of direction, or needs to be aborted. For instance, Google requires that project specs be no longer than one page, a limit that helps reduce any reluctance or regret about changing course or winding down.37

Organization

The adaptive approach needs an organization that is able to capture and share external signals and to generate and manage a portfolio of experiments effectively. The necessary organization design principles, therefore, are to be externally oriented, information enabled, decentralized, and flexible to reallocate resources quickly as the focus of experimentation evolves.

An external orientation allows firms to capture external signals effectively. Often, this means that a firm embeds customers into its processes by building strong feedback mechanisms or by creating user communities as part of its organizational model. Sometimes, customers are even a main source of innovation ideas.

Adaptive firms are typically broadly information-enabled and make data visualization and analytics available throughout their organization, so that employees can spot change and formulate an immediate, fast response. This is different from the classical approach, where the analytical tools used for strategizing are usually concentrated among a small group of expert professionals.

Because of the need to stimulate bottom-up learning and individual creativity, adaptive organizations often foster a high degree of autonomy and are relatively flat and decentralized. The organizations are often characterized by the existence of informal, temporary, or horizontal structures, like internal forums, task forces, or councils that break down traditional functional silos to allow for sharing of information and flexibility in mobilizing around promising opportunities. Multiple layers, strict hierarchy, and a thick rule book would greatly reduce a company’s ability to execute a quick about-face in light of new signals from the environment.38

Safe Innovation Space: Organization at Intuit

Intuit is what its president and CEO, Brad Smith, calls a “30-year old start-up.”39 Despite being an “old”—that is, pre-internet—software company, Intuit has continuously rejuvenated its fortunes by retooling its innovation and experimentation processes to design cutting-edge financial software. Senior leaders at Intuit designed an organization that functions as a safe innovation space by reducing friction in new-product development and encouraging a philosophy of speed, guided by simple rules.

For instance, Intuit’s organization fosters openness, flexibility, and bottom-up contributions by empowering small, diverse teams of four to six people to identify problems and to prototype solutions rapidly. When an internal task force determined that too many managers were involved in new software releases, making the process inefficient, unclear, and sometimes demoralizing, the group rolled out a new decision process that grants far more authority to the small scrum teams that best know the product and target customers. Management’s role in each decision is limited to a pair of approvers: one sponsor to remove roadblocks and one coach to provide vision.40

Intuit’s organizational rules and processes serve less to constrain the organization than to empower and focus it. Faced with possible commoditization from free internet services, Intuit has maintained its leadership through a combination of new products and smart acquisitions, including the personal-finance aggregator Mint.com. Since Smith became CEO in 2008, Intuit stock has more than doubled.41

The adaptive organization is typically modular and flexible, which means that its units can be recombined quickly, depending on shifts in the environment or the decision to scale a particular experiment. Standardized (plug-and-play) interfaces enable the organization to morph to address changing needs by rapidly shift resources. Take Corning, the maker of Gorilla Glass, which has been used as a cover material for iPhones through 2014, along with nearly twenty-five hundred other devices across thirty-three major brands.42 As we will explore in chapter 7, Corning doesn’t know far in advance when device manufacturers will begin to build a new product or what the specs will be. But the company’s flexible organizational structure, lack of silos, and common incentives allow it to adjust roles and reallocate resources quickly to mobilize around new opportunities.

Culture

An adaptive firm’s ability to read and act on market signals and conduct experiments is underpinned by its culture. Adaptive cultures are therefore externally oriented and means focused. The culture creates the context for the generation of new ideas and rapid learning by allowing for a diversity of perspectives and encouraging constructive dissent, rather than compliance with a single mandated direction.

In contrast to the expressly goal-oriented, disciplined culture in the classical firm, the adaptive approach requires a culture of openness and playfulness to encourage the generation of new ideas. The culture promotes challenge by allowing constructive dissent and promoting cognitive diversity. And because adaptive organizations rely on individual creativity and initiative, they articulate a set of common behaviors and a common purpose in the place of precise endpoints.

Netflix, for instance, is unique in the way it first codified an explicit set of adaptive management beliefs and principles. Here is an example from its “Reference Guide to Freedom and Responsibility Culture”: Process-driven companies are “unable to adapt quickly, because the employees are extremely good at following the existing processes . . . we try to get rid of rules when we can. We have a culture of creativity and self-discipline, freedom and responsibility” that benefits from “highly aligned, loosely coupled teamwork . . . the goal is to be big and fast and flexible.”43

The culture at Netflix has underpinned sustained viability and superior operational and financial performance in a highly turbulent industry. As Netflix has evolved from providing mail-order DVDs to streaming digital media to developing independent content, its stock price rose tenfold from 2009 to 2014, and Netflix became the largest source of internet traffic in North America in 2013.44

Leadership

Adaptive leaders lead through setting context, rather than goals. They do this by orienting the organization externally, creating an experimentation-friendly culture, specifying the rules under which experiments are conducted, and highlighting the areas where experimentation is to be focused. Reed Hastings, CEO and founder of Netflix, summarized this important quality of leadership: “The best managers figure out how to get great outcomes by setting the appropriate context, rather than by trying to control their people.”45

Culture and Leadership at 3M: William McKnight

William McKnight officially became president of 3M, an industrial conglomerate, in August 1929—just two months before the Wall Street crash. Over the next twenty years, he ran a company that needed to cope with a great deal of change. His achievement stands as the classic case of a leader creating the context within which his team of brilliant innovators could shine.

McKnight formulated a set of management principles that could be remarkably applicable to any innovative technology companies’ culture today: delegate responsibility to stimulate individual initiative; tolerate mistakes to avoid dampening the spark of creativity; allocate free time in the working week for people to pursue their own interests; establish platforms so that great ideas can be shared across the organization.

As he prepared to step down from his role as president in the late 1940s, McKnight set down these principles in a code for the leadership team that would be assuming the day-to-day control of the company:

As our business grows, it becomes increasingly necessary to delegate responsibility and to encourage men and women to exercise their initiative. This requires considerable tolerance. Those men and women, to whom we delegate authority and responsibility, if they are good people, are going to want to do their jobs in their own way. Mistakes will be made. But if a person is essentially right, the mistakes he or she makes are not as serious in the long run as the mistakes management will make if it undertakes to tell those in authority exactly how they must do their jobs. Management that is destructively critical when mistakes are made kills initiative. And it’s essential that we have many people with initiative if we are to continue to grow.46

Today, these principles continue to set the context for 3M’s employees. The company encourages its R&D staff members to exercise their initiative by giving them as much as 15 percent of their time for “tinkering,” often on basic research topics with no obvious or immediate commercial potential.47 In other words, “Google Time” has been around far longer than Google. These organizational and cultural elements are central to 3M’s enduring success. 3M often exceeds its own goal to generate 30 percent of its sales from newly launched products.48

Tips and Traps

As we have seen, successful adaptive strategy hinges on continuous, disciplined execution of signal-guided, iterative experimentation rather than preset goals. To conduct such experiments effectively, you must accept the limits of your knowledge and your powers of prediction and prepare for the future by creating and exploiting options, rather than by deriving a single, unchanging plan through analysis and prediction.

ARE YOUR ACTIONS CONSISTENT WITH AN ADAPTIVE APPROACH?

Your approach to strategy is adaptive if:

![]() You aim to capture and decode change signals early.

You aim to capture and decode change signals early.

![]() You create a portfolio of options and experiments.

You create a portfolio of options and experiments.

![]() You select successful experiments.

You select successful experiments.

![]() You scale up successful experiments.

You scale up successful experiments.

![]() You reallocate resources flexibly.

You reallocate resources flexibly.

![]() You iterate (vary, select, scale up) rapidly.

You iterate (vary, select, scale up) rapidly.

Volatile, unpredictable environments and adaptive strategies are much discussed and are, superficially at least, familiar to most managers. Not surprisingly, then, a quarter of the companies in our survey declared that they had adaptive approaches to strategy, and more that 70 percent think that plans should evolve. Nevertheless, many companies acknowledged that they have insufficient adaptive capabilities: only 18 percent and 9 percent saw themselves as expert at reading signals or managing experimentation, respectively. Few companies, however, appeared able to identify adaptive environments accurately, and many companies tended to read such environments as more predictable or malleable than they actually are. Moreover, even when firms declare an adaptive approach, the practices the companies actually used—planning, prediction, emphasis on ends rather than means, and the like—tended to be decidedly nonadaptive. Our survey painted a clear picture of many companies recognizing the importance of adaptive approaches but having insufficient knowledge or experience of how to operationalize this understanding. Hopefully, this chapter and the tips and traps presented in table 3-1 will help remedy this gap.

TABLE 3-1

Tips and traps: key contributors to success and failure in an adaptive approach