Chapter 1. Down the Rabbit Hole

The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.

— Joseph Campbell

The entire situation was unfamiliar. I was in a part of the world I had never seen—the foothills of the Trinity Alps in Northern California, deep in the heart of Humboldt County, where the cell phone reception seemed as prehistoric as the surrounding landscape. We completed the seven-hour drive from San Francisco, through the giant redwood forest, to explore the Hall City Cave. The beam of light emanating from my headlamp exposed vivid details: threatening stalactites, a rock wall covered in spiders, and a few inverted, sleeping bats. I was carrying a large yellow Pelican case containing an underwater robot I had helped design and build. That was really new.

“I think the next time we do this, we should wait until the summer,” I said to Eric as I handed him the case to get a better footing as we descended further into the cave. The clunky, waterproof boots I was wearing were not the best choice for spelunking, but they were my only option given the awful weather outside the cave. He looked at me and smiled. It was obvious to all six brave souls who made the trek that choosing a January date for our trip to the cave was not wise. With such a dry and mild winter we thought Mother Nature might spare us a few more nice days, but we had pushed our luck. The heavy, constant snowfall was an hourglass constantly reminding us of how little daylight was left and how much worse the return trip could get.

My remark to Eric was meant to be lighthearted. A series of nearly trip-ending incidents had left the group exhausted. We woke up to worse-than-expected weather and were forced to scramble to find chains for our car tires. After we made it up the mountain, we found the back roads to be impenetrable. Luckily, we met a local Wildwood resident who offered to help plow us through the snow-covered back roads. By the time we reached the cave, everyone was tense and tired.

Ever since Eric Stackpole and I first met and talked about underwater Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) and ocean exploration, we had been plotting for this moment. Eric tells the backstory, The Legend of Hall City Cave, much better than I do; it’s his favorite story to tell and he will share it with anyone willing to listen, whether it’s a full auditorium or a small dinner party. He always starts out the same way: ensuring that his audience has a full 90-second attention span to dedicate to his tale. He shakes out his arms and takes a deep, preparatory breath, “Whooooosh!” A wave of his hands and an exaggerated exhale take them back in time:

Flashback, 1800s. Northern California. Gold rush. Two Native American men rob a gold mining operation and make away with an estimated 100 pounds of gold. A sheriff’s posse is assembled to track down the men. After days of chase, they eventually catch the two men, but they no longer have the gold. The sheriff’s posse makes an offer, “Tell us where you hid the gold and we’ll spare your lives.” The men explain that they hid the gold in the Hall City Cave. Despite the sheriff’s promise, both men are hung on the spot. The posse returns to the area the men described and, sure enough, there’s a cave. They don’t find the gold, but toward the back of the cave they find a hole six feet in diameter and filled with water. The underwater cavern extends down further than they can see, and they lack the tools or technology to explore further, so the sheriff’s posse gives up.

Eric ends the story by recounting the numerous cave divers and treasure hunters[1] who chased the legend as far as a human diver could possibly explore, without ever finding the bottom. His final line is “and that’s why we’re building this underwater robot: to solve the mystery of the Hall City Cave.” More information on the story of Hall City Cave is shown in Figure 1-1.

I’ve heard the story a hundred times, and it never gets old. When Eric and I first met, that’s really all it was: a great story and a rough prototype of a robot he wanted to build. Even though I didn’t have any relevant technical experience, I knew I wanted to be a part of the adventure. The idea of exploring the unknown with an ingenious tool made from off-the-shelf parts held me in its grip. It struck a chord inside me that my office job couldn’t possibly reach.

Now, as I walked inside the cave with Eric and the ROV, I could hear my own heartbeat. About 15 meters inside the cave, descending its rocky steps and twisting caverns, part of me still didn’t believe the underwater hole was real; could it be that this was just an urban legend to lure tourists into the Wildwood Store just a few miles away? Part of me began to doubt the whole thing. But as we came upon what seemed to be the end of the cave, we flashed our lights toward the floor and there it was: a hole six feet wide, filled with crystal-clear water deeper than the flashlight could illuminate. Just as the story told.

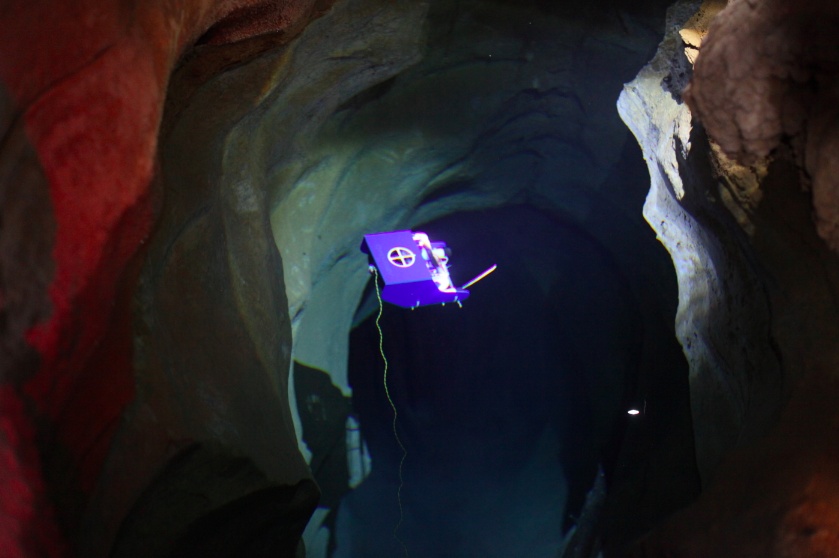

Eric set down the Pelican case near the underwater opening and took out the ROV. The combined direction of our headlamps lit up the work area, as shown in Figure 1-2. As we inspected the robot, Eric noticed the walk to the cave had caused one of the propeller ducts, the circular guards that wrap around the propeller, to crack off—not ideal, but not critically important. We decided to break the opposing duct to make it proportionate.

Even without the propeller ducts, the robot is a beautiful piece of bare-necessity engineering. Well, at least beautiful once you know what you’re looking at. Like most underwater creatures and contraptions, it looks awkward out of its natural habitat. The brain of the ROV, the main electrical system, is housed in a clear plastic cylinder that includes the camera, three speed controllers, and the micro-controller. The cylinder resembles a large French press, except horizontal, filled with electronics and built to withstand pressure. It’s kept air-tight with plastic end-caps. Wires and communication lines protrude from the end-caps and are potted with epoxy. In addition to keeping the electronics dry, the cylinder also serves as the main force of positive buoyancy to keep the ROV upright underwater. The outer shell of the ROV is a sheet of blue acrylic plastic that folds tightly over the cylinder, like downward folded wings. The wings extend down to the battery packs—six C batteries, three on each side—that also act as ballast to counteract the air-tight container. Add in the motors, propellers, and a few threaded steel rods, and the entire robot is still only about the size of a small microwave.

Eric started in with the last minute waterproofing, while I added weights to the steel rods to make sure that the robot had the correct buoyancy. Brian Lam, our photographer, arranged flashlights and made sure the cameras were rolling. Jeff Bernard and Bran Sorem, friends who had decided to join us for the trip, maneuvered themselves along the wall of the cave in order to shine lights into the cavernous depths. Zack Johnson, another friend and robot collaborator, unwound the tether, which would be the communication line to the robot when it was underwater. The moment of truth was finally here.

Eric walked over and set the robot into the water. It floated on the surface and we collectively held our breath and waited for the robot’s next move. The LED lights switched on, like an infant opening its eyes. The silence was broken by the buzzing of the robot’s propellers. Sporadic at first, it took several thrusts before we felt comfortable with the controls. Almost at once, the mood in the cave completely changed. The nervous anticipation around whether the ROV would even work was replaced by a playful excitement; what could this thing actually do?

The lights from the robot lit up the water, creating a vivid display of the interior of the underwater cavern. The lighting caused the cave walls to radiate deep blues and purples. With precise control, the robot descended into the depths. Watching it dive made my heart flutter. I couldn’t believe we had come this far. After all the designing, testing, and re-designing, it was really starting to become clear: we had accomplished an amazing feat of collaborative creation. Building this robot was a product of collective passion and commitment. We had to overcome a myriad of design and technical challenges to arrive at this point. We set out to make a capable underwater ROV that could be used for exploration, using only off-the-shelf parts and tools that are accessible to everyone. Also, we wanted it to be far cheaper than the commercial products that were available. And we had done it.

I didn’t just take pride in what we built but also in how we built it. The design was Eric’s baby, something he originally conceived and muscled into the world. But the current version of OpenROV—the model that made the trip to the cave—was a distant relative of Eric’s original prototype. This model was something much greater. From our very first conversation, Eric and I decided to make the project open source, meaning we release the designs, production steps, and bill of materials online for anyone to see and use. We created a website, OpenROV.com, where we displayed the build information and also problems that we were encountering. It started out as a way to show our friends what we were up to, but quickly grew from there. A few months into the project, we were getting advice and support from people all over the world, most of whom we had never met, some with extensive underwater robotics experience. The feedback, suggestions, and insights from members of that community were key to overcoming our challenges. By the time we found ourselves in the cave, the project had benefited from hundreds of contributors, spanning dozens of countries.

We ran the robot down the large cavern and into small offshoots that piqued our interest, as shown in Figure 1-3. At one point, the entire group erupted in cheers as we safely threaded the needle of a tight opening in the rocks. We came across a number of interesting artifacts: a long piece of tubing, some sunglasses, and an old lighter. Items you could imagine a group of teenagers dropping in during an afternoon adventure. We spent so long exploring that we eventually ran out of batteries. Luckily, we had navigated the robot back to a point where we could easily fish it out with the attached tether. It was a silly and humorous mistake in an otherwise successful maiden voyage.

We didn’t end up finding any treasure in the cave, but it didn’t matter. We had built the robot we dreamed of and, more important, had an adventure doing it. We met hundreds of new friends and collaborators and discovered there were a lot of other people interested in what we were doing. The process was far more valuable than the outcome.

For me personally, the real treasure was never gold, but something far more precious. This maiden voyage of our little robot was a tremendous experience, but my journey started long before that day in the cave. My challenges were more fundamental than any technical design. I had gone from non-existent engineering or design experience to making substantial contributions to underwater robotics. A project that had seemed intimidating and impossible to me only a year earlier shaped me into a completely new person. I had flipped the switch from being a passive consumer of life to an engaged, creative participant in it. I had gone from Zero to Maker.

It all started on a June morning—six months before the trip to the cave—in a small office in Los Angeles. That morning unfolded like most others. I was in early before any of my coworkers had arrived and was busy answering emails and responding to client issues. I didn’t expect that it would turn into a judgment day of sorts.

As a startup, we were struggling; revenue had trickled to a halt, investors were backing away, and the attitude around the office was bleak. The plan was to meet at 9:00 am for a team meeting and strategy session. When the founders of the company arrived late and asked only me to come into the conference room, I knew it wasn’t going to be good news.

They were letting me go.

Just like the headlines I had seen for the past two years—more layoffs, jobs eliminated, and record unemployment—but delivered with a piercing stab. It was no longer happening around me; it was my new reality. The next day, as the shock continued to set in, I took a long walk through the hills of Los Angeles trying to make sense of it all. I couldn’t help but think back on the events that led up to this moment, trying to excavate some sign I overlooked in the haze of unshakable confidence in being on the right path: a good college education, strategic work experience, and a job with a promising young startup company. Then suddenly, on a sunny Tuesday morning, it was gone.

I walked for hours and came to the realization that this was bigger than just losing a job. More important, I felt that in this work shake up, my life story had been stripped away from me. My personal narrative—my sense of purpose and direction in the world—no longer made sense. I had spent so much time justifying my actions (and time spent as a slave to a computer monitor) with the rationale that I believed in the mission of our company. I tried to get back on track mentally by telling myself I’d get another job. I dusted off my resumé—something I hadn’t needed to do in years—and just stared at it. I re-formatted and updated my experience, but after all the tweaks and sorts, something still wasn’t right. I kept questioning myself: What was I doing, really? No matter how I told my story, I realized, I couldn’t hide one glaring fact: The only thing I was qualified to do was to sit in front of a computer.

To make matters worse, my anxiety over being jobless was compounded by a blooming awareness that I was in a completely wrong business to begin with. It so happens that a year before I lost my job, I had attended a Maker Faire based on a friend’s recommendation. She thought I’d enjoy the crowd and the eclectic nature of the gathering. She was right. The Faire blew me away. The interesting projects—robotics, crafts, and massive installations—were only outdone by the passion and energy of their creators. In my wildest imagination, I could probably conceive of a few of these contraptions and characters, but never all in one place—in this bizarre environment where giant unicycles and autonomous robots blend into the crowd. Most strikingly, I couldn’t believe these individuals and groups were able to actually build this stuff. I didn’t quite know how, but I wanted to be more like them. Thinking and learning more about what I’d seen at the Faire that day led me to Eric and his ambitious plan to build his own submarine. I wanted to help with the robot adventure, though I wasn’t sure how I could contribute. Without even a basic high-school shop class education, let alone any kind of engineering degree, I had felt disqualified from even trying.

The jobless wandering and the maker longing were a powerful mixture in the days and weeks after being laid off. The more I thought about it, the more I realized how tragically specialized I had become. I was extremely well prepared for a job that no longer existed, without the fundamental skills I could repurpose elsewhere. I seemed to be far away from being able to build, fix, or create anything of tangible value—any real, physical thing. My so-called skills—emails, social media, and blogging—were hollow substitutes. Now, after hurtling in and out of a digital career, I felt as though I were missing a critical piece of my humanity.

Over the course of the following weeks, my awareness of my manual illiteracy only grew. I met a carpenter at a flea market who was selling handcrafted tables and desks. He explained to me that he used his tables to pay the bills while he pursued a comedy career in the evenings. I envied his resilience. His woodworking skills were something no one could take from him. Unlike my startup job, no one could tell him to stop making tables.

Soon, my desire to re-educate myself with basic making skills overshadowed my worry about finding a new job. I found myself thinking that getting another job would just be a distraction to a bigger goal, delaying the inevitable recovery of a missing vital element of my education.

I wanted to do something about it, but I wasn’t sure where to start. I decided to begin with the only lead I had: Make: magazine. In addition to putting on the Maker Faire, Make: publishes a quarterly how-to magazine filled with interesting projects and makers. It also publishes a popular blog at Makezine.com.

I wrote out a long email explaining my situation to the Make: editors, highlighting my suddenly free schedule and dedication to learning the skills and tools that I felt I’d missed out on. I proposed that I would do my best to become a do-it-yourself (DIY) industrial designer before my savings ran out, and blog about my entire experience for the Make: blog. I packaged the whole idea under the title “Zero to Maker in 30 Days” and I sent it off.

It was a shot in the dark, but lucky for me, they liked the idea. And now I had a written commitment to follow through on, regardless of how it turned out.

What started off as a one-month commitment to learn new skills turned into a life-changing journey. I quickly discovered that my initial trip to Maker Faire was simply the tip of the iceberg. I continued to meet more makers—a growing community of people who have adopted and rewritten the idea of DIY—and they were nothing like I expected.

Before I dove into making, I barely knew which way to hold a hammer. I wasn’t sure if I could fit in or how the Make: readers would receive my eagerness to participate. All the makers I had met seemed brilliant, whereas I felt like an average guy, genetically disposed to being uncoordinated and uncreative. How was this going to work?

I had some preconceived ideas about makers: who they were, how they worked, and how they learned. I imagined the process to be a long, lonely, and tedious study of engineering, tools, and science—skills I had bypassed on the fast track to be more “marketable.” As it turned out, my initial assumptions were completely off. I quickly realized that these preconceptions were, in fact, the toughest obstacle I would need to overcome. When I recognized how unfounded they were, my own inner maker was able to come crawling out of his shell.

First, I learned how makers really worked. My first trip to Maker Faire left me with the impression makers were lone geniuses, toiling away in garages or workshops, putting countless hours into a project, repair, or invention and coming together once a year at Maker Faire to show off their creations. This couldn’t have been further from the truth. Making is definitely a team sport.

Makers are, above all, a connected and collaborative bunch. They meet online and share ideas on forums, blogs, and discussion groups. They give away their designs and collaborate on projects with people all over the world—the exact opposite of the competitive secrecy I had come to know in the corporate world. They’ve pooled resources to create “fab labs” and “makerspaces,” which are physical spaces that serve as hubs for sharing costs and maintenance of larger tools and equipment. It didn’t take me long to understand that little of anything is being done “yourself.” Making is actually not about DIY, but rather all about DIT, or Do-It-Together.

The next realization came when I began to learn about the new tools these makers were using. Before my immersion, I had a sentimental notion that DIY was about bringing back a bygone era, a time before hammers and nails were replaced with video games and iPads. I imagined DIYers to be torch-bearers, keeping alive the methods and craftsmanship that were marginalized by the onslaught of computer screens and advertisements. I wanted making to help me connect with something I felt had been lost over the past few generations—a part of being a self-sufficient human that was missing from my life.

In a way, makers are the guardians of this industrious self-reliance I had hoped for, but together they’re so much more. They understand and respect their place in history, as part in a long line of tool makers and tool users. Although they keep traditional knowledge alive, they are also busy inventing and bringing new technologies into the world. And these are not your grandparents’ tools.

The new maker tools are byproducts of increasingly affordable computers, components, and sensors. They are fueled by the rapid exchange of ideas on the Internet and are empowering individuals and small groups with a whole slew of new personal fabrication tools. Laser cutters, 3D printers, and other computer numerical control (CNC) machines (automated machine tools) are now affordable enough to be purchased for a home or office workshop and capable enough to create customizable, consumer-ready products. A product that 15 years ago cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to prototype and produce can now be created with a downloadable file and access to one of the numerous makerspaces that are popping up in cities all over the world.

And learning to use these new tools was shockingly easy, as I discovered. When I started, I predicted I would need an industrial design or mechanical engineering degree before I could make anything useful or valuable. I never imagined I could come so far in such a short period of time. In only a few months, I was 3D printing, teaching others how to use the laser cutter, and designing basic parts in computer-aided design (CAD) programs. I had started welding, working with sheet metal, and creating plastic molds. I was clearly not a master welder and certainly not the best microcontroller programmer, but I knew enough to get started. Anything I didn’t know—how to use a machine, what material to use, how to assemble something—I could just pick up on the fly. I learned skills as I needed them, depending on the specific problem facing me. And I was never alone. All the makers I met seemed to specialize in one area or another, and everyone was happy to teach what they knew. In fact, I discovered that everyone still had a lot to learn, but we were all able to leverage one another’s skills and knowledge.

As soon as I let go of my misconceptions, I was welcomed into a community of possibility. I realized I was part of something larger: a maker movement. I also discovered my experiences were not unique. This is how all of the new makers were informally inducted. In exploring this new world, I saw a new side of myself, a part that revels in the process of creating and sharing with others. I learned what I was capable of, and it was far more than I imagined.

Even though these observations of “Doing-It-Together” and learning from one another were a revelation for me, I soon discovered that this radical collaboration had been there from the start of this new maker renaissance—rooted all the way back to an experimental class at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) over a decade earlier.

In 1998, MIT Professor Neil Gershenfeld and his colleagues dreamed up a “fab lab,” an assembly of high-tech machines that could build other machines, which he describes as using “supersonic jets of water, or powerful lasers, or microscopic beams of atoms to make—well, almost anything.”[2]

The biggest problem they encountered was that none of the students knew how to operate the new tools, so they decided to teach a semester-long course that would serve as an introduction to the fab lab. Thus, the class “How to Make (Almost) Anything” was born.

The class was originally designed as a primer for a small group of advanced students, but quickly evolved into something more as a hundred—from nearly every academic discipline—tried to enroll. The class was a huge hit and was taught for many subsequent semesters. The experience gave Gershenfeld a glimpse into the future of personal fabrication and much of what he saw surprised him, especially with regard to how students were learning. In his book FAB: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop—From Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication, Gershenfeld describes the scene in his class:

The final surprise was how these students learned to do what they did: the class turned out to be something of an intellectual pyramid scheme. Just as a typical working engineer would not have the design and manufacturing skills to personally produce one of these projects, no single curriculum or teacher could ever cover the needs of such a heterogeneous group of people and machines. Instead, the learning process was driven by the demand for, rather than the supply of, knowledge. Once students mastered a new capability, such as waterjet cutting or microcontroller programming, they had a near-evangelical interest in showing others how to use it. As students needed new skills for their projects they would learn them from their peers and then in turn pass them on… This process can be thought of as a “just-in-time” educational model, teaching on demand, rather than the more traditional “just-in-case” model that covers a curriculum fixed in advance in the hopes that it will include something that will later be useful.

The “just-in-time” learning model that Gershenfeld described jumped off the page. It was exactly the way I had learned about making. And it wasn’t a coincidence: this is how all makers learn.

In my first entry on the Zero to Maker column, I mentioned that my goal was learning enough to be dangerous. At the time, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I made the comment because I wanted to set the bar low enough that I could achieve it. I didn’t expect to become a master of any of the tools, trades, or technologies. Instead, I just wanted to feel them with my own hands and learn how they worked. I wanted to see what was possible.

This turns out to be the best possible strategy I could have taken. After talking to other makers, seeing how everyone operated, and reading second-hand accounts like Gershenfeld’s FAB, I realized that was what everyone was doing: exploring what is possible.

In retrospect, it seems silly that I was ever nervous about getting started. There was only one lesson I needed to learn. Actually, it was a choice. I had to choose to become a beginner, to get comfortable with mistakes, to ask a lot of questions, and to seek out the right teachers. After I crossed that bridge, everything else fell into place. Makers are a community of beginners, and we’re all learning together.

It’s easy for me to say, without hesitation, that my quest to become a maker changed my life. But more than that, it has become my way of life. The quest to re-skill myself turned into a fundamental re-thinking of how I view opportunity. And I’m not alone.

What started as a series of garage inventions and side projects has turned into a budding industry, with makers of all different shapes and sizes turning their fervor, skills, and ingenuity into businesses and careers—turning their passion and creativity into entirely new business models based on community and collaboration instead of the old model of cutthroat competition.

The businesses take many different forms. Some are a throwback to traditional craftsmen; artisans that create largely custom and specific pieces of work for a small community of clients and customers. People like Joel Bukiewicz, a knife maker in Brooklyn, discovered that there is substantial demand for his handcrafted cooking knives. After struggling for many years to find work as a writer and suffering a crisis over his career direction, Joel turned his attention toward making and quickly fell in love with the process of creating knives. But his story isn’t a harrowing tale of a spurned writer succumbing to isolation and madness a la Stephen King. Instead, in Brooklyn Joel discovered a vibrant community of other makers who share and collaborate to support one another’s businesses.

When I asked Joel about his business, he couldn’t stop talking about how valuable this environment has been to his development. As soon as he opened up a physical store and showroom, his business took off. He was learning from his audience: what they liked, where and how they were using his knives, and how much they would pay. It was more than a store; it was a catalyst for building his community.

Internet platforms like Kickstarter and Etsy combined with new creative communities like the one Joel discovered in Brooklyn have created a new economic infrastructure for these 21st century artisans to prosper.

Small, community-oriented artisans are not the sole constituency of the movement. Makers are also the driving force behind the proliferation of technologies and platforms like 3D printers, CNC machines, and microcontrollers. Fast growing companies like MakerBot Industries are building and selling desktop 3D printers based on open-source designs.

When I was just getting started with making, I kept hearing about 3D printing. Everyone was talking about it and I had no clue what it meant. It was originally described to me as something very similar to a regular inkjet printer, except that instead of putting ink onto paper, it lays down a thin layer of plastic. Layer after plastic layer, it repeats the process until it has created an actual 3D object. The process continued to baffle me until I actually sat down with a MakerBot and learned how to use it. At its core, the process is as easy as clicking print and waiting twenty minutes for your creation to appear inside the machine. Watching the MakerBot in action helped me to understand what all the commotion was about; there’s something magical about printing out an actual, tangible object from a set of digital instructions.

The global community of hobbyists-turned-entrepreneurs has taken 3D printing, a technology that once was only available to researchers and wealthy corporations, and made it affordable enough to be purchased by an individual or small group and used in homes and offices in addition to academic or corporate research facilities. Instead of supporting proprietary research and development arms, these new 3D printing companies have innovated by openly sharing their designs and allowing their communities to give feedback to the product development. Drawing from the open-source software playbook, this model of open-source hardware is enabling small actors and teams to compete with much larger corporations and established businesses because of its leaner and more flexible approach, a strategy I’ll cover extensively in Chapter 5. MakerBot and the others have a ways to go before their affordable desktop printers are as capable as the expensive, proprietary models, but they’re doing an excellent job of making them easy for new makers, like me, to get into the game. And the maker tools are getting cheaper, more capable, and easier to use every day.

Large corporations are watching this trend, too, and making big bets that this new form of distributive, small-batch manufacturing takes hold. Corporations like Autodesk are busy building design software that enables new makers to quickly pick up the CAD skills they need to get started designing parts and components. Companies like Ford are becoming major partners in makerspaces like TechShop in order to give their employees access to cutting edge equipment. They are betting that innovation comes from empowered, front-line employees. By encouraging their employees to tinker with projects they’re passionate about, the companies are hoping to unlock creativity that previously had gone unrealized. Suddenly, making is relevant for more than just the tinkerers and hobbyists who do it for fun. It’s a new skill set that can help employees advance in larger organizations.

These major trends—tech-enabled individuals and community-based business models—are all pointing in the same direction: opportunity. In a time when job and career uncertainty are at an all-time high, it’s refreshing to see a budding industry (many industries, actually) with so much potential. The maker movement is waiting for people like you to figure out what’s next. To use a skiing metaphor, the mountain is covered with a thick blanket of fresh snow—you can go in nearly any direction, but you have to carve your own path.

This book is meant to be a map. It’s meant to give you a view of the maker landscape and get you up to speed as efficiently as possible. I have made the transition from Zero to Maker myself in just a few months and witnessed countless others do the same. Based on those lessons, I have created an easy-to-follow formula for avoiding the pitfalls and hurdles that can hold you back. This book is meant to put you in a position to make anything you want, even (and especially) your own business. It is designed to enable. To use the skiing metaphor again, think of this book as the chair lift—carrying you over the freshly covered slopes to give some perspective and dropping you off in a position to get started on your own thrilling run.

[1] Eric originally heard about the cave from a friend and got most of his initial information from Dave McCracken’s website.

[2] Neil Gershenfeld, FAB: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop—From Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication (Basic Books, 2007).