The Fourth Step

PLAY

How to Free Your Mind to Imagine Possible Worlds

For many of us, text messaging is like breathing—necessary, automatic, and reflexive. It hasn't been around very long, though: it's based on Short Message Service (SMS), a technology that's only been available on cell phones since the early 1990s. When SMS was first invented by the Dutch company CMG, it was designed to be used strictly for internal maintenance purposes. For example, CMG used it to broadcast messages to its customers about network problems, and to notify them if they had a voice message.

CMG had no plans for customers to send messages to each other, but amateur hackers in Europe, playing around with their phones, somehow stumbled on a way to do it. Then, to their delight, they discovered that this new pirated messaging system was free! The phone companies hadn't designed any way to track usage. Word spread fast; before long, teenagers across Europe—who often bought prepaid mobile phones—all knew that every text message was free. Suddenly, millions of messages were flying back and forth every month, and phone companies were scrambling to figure out how to bill per message.

Text messaging, now the norm, was not a corporate invention dreamed up in a research lab. It emerged from the zigs and zags of play and exploration.

There's an intimate connection between play and creativity—why?

- Play is when you let your mind wander. You put aside the hard work of the first three steps, you relax, and you give your subconscious time to work its magic.

- Play is when you enter the province of the imagination. Instead of dealing in precut, dry, dusty old facts, you envision what's possible. You create alternate worlds, making them more colorful and interesting, smarter and more meaningful, than the current reality.

Children are naturally creative. They experiment tirelessly, combining things that aren't supposed to go together—marbles and Play-Doh, race cars and bouncy balls. They paint purple grass and give trees arms; they dress penguins in top hats; and they never, ever fear looking foolish. They let their minds wander freely, and they visualize the ridiculous so well, it's often clever.

At the 2008 Art Center Design Conference, Tim Brown, the head of IDEO, gave the audience members thirty seconds to draw the person sitting next to them. You could hear the giggles, groans, and apologies as they sketched. Afterward, Brown pointed out that children, given the same task, show no embarrassment whatsoever. They happily show their masterpiece to their model, because they haven't learned to fear judgment. And fear is what inhibits creativity, making us conservative in our thinking and timid in our execution.

The techniques in this chapter help you summon back that childlike instinct to toy with the world, to pretend, to try on exotic costumes and turn everyday objects into props and cardboard boxes into a kingdom.

Adult life is filled with pressure and deadlines. To create the space for imagination, dreaming, and insight, it is your solemn duty to master the discipline of playing.

The boss was on vacation, wiggling his toes in hot sand on a beach in the Caribbean. The year was 1976, and the boss was John Reed, the executive in charge of Citibank's checking account and credit card businesses. At every big New York bank, these lines of business were famous money losers; no one had been able to figure out how to make money on checking accounts and credit cards. (I know, hard to believe, right?) All the banks made a neat profit on business clients, but lost money on people like you and me. Reed was a rising star at Citibank; he'd just been put in charge and told to figure out a way to make these businesses profitable. He was facing a huge challenge. It was time to play.

I know, some of you might say, “Wait a minute, that guy makes a handsome salary, and his business is losing money—why does he deserve a vacation?” But Reed wasn't just being selfish; he knew that he often had his best ideas while playing. He carried a notepad and a pencil all over that Caribbean resort. And one day, lying in his beach chair staring out at the waves, he saw the solution. He reached for his pad and started writing…

That day on the beach, Reed wrote more than twenty pages. At the top of the first page, he put a title: “Memo from the Beach.” Then he proceeded to draft the blueprint for a completely new kind of consumer bank. Customers could get their cash from a street-level machine; no need to wait in line for a teller. The machine could even tell you your account balance. Sounds familiar, right? But when Citibank installed ATMs all over Manhattan in 1980, it was the first and only bank in the world to have them.

“Memo from the Beach” also described a new way to market credit cards: nationally and through the mail. But in 1976 there were some old nineteenth-century banking laws still on the books that made this very difficult—banks couldn't market nationally because they had to deal with different lending laws in every state. When a Supreme Court ruling changed this in 1978, Citibank already had a strategy in place—right there in the “Memo from the Beach.” All the company needed was to find a state willing to host its national credit card operations, and by 1980 Citibank had found a home. (Hint: It's not Delaware. See the bottom of the page for the answer.)1

Today we take it for granted that we can get cash from a machine, twenty-four hours a day. We often take it for granted that our credit cards (and, alas, their monthly statements) come in the mail. But if Reed hadn't gone to the beach and made some space for his imagination to play, this might never have come to pass.

Exceptional creators are masters of the discipline of play, the ability to imagine and envision possible worlds. Some of the most exceptional creators are also the most extreme players, as shown by researchers Robert and Michele Root-Bernstein. They interviewed ninety MacArthur Foundation genius grant recipients, and were surprised to find that quite a few of them engaged in what's called worldplay—the creation of elaborate imaginary worlds—when they were children.

- The invented land of Mystica, inhabited by people and other creatures and replete with maps and histories

- A “rainbowhouse” in which the child “lived with imaginary animals and cartoons I loved” and bedtime stories woven around people who “lived in the clouds and at night would come into your dreams”

Twenty-three of the ninety geniuses—about 25 percent—engaged in worldplay. (In a comparison group of typical undergraduate students, only twelve percent engaged in worldplay.) And most of those twenty-three geniuses felt sure there was a connection between their childhood worldplay and their creative success as adults.

Here's another intriguing discovery: guess how many of the extremely successful geniuses said that they engaged in worldplay as adults? A whopping 57 percent—that's even more than said they had engaged in worldplay as children! One genius said: “In a real sense to do theory is to explore imaginary worlds because all models are simplified versions of reality, the world.”

Another genius said:

My childhood was fairly rough and tumble, always racing around the neighborhood, building things, starting “businesses,” coming up with new “inventions” (that never worked), launching ourselves into outer space, saving bugs in jars, digging holes to China—in memory, at least, all fresh, unfettered, and teeming with possibility. My work today is pretty much the same thing.

Play works because it taps into your subconscious mind—and research shows that great ideas usually emerge from the subconscious. They only arise after you've identified a good problem, in the first step (ask); and filled your mind, in the second and third steps (learn and look). Once you've fed your mind well, it's time for your subconscious to get to work, mixing all of those ideas together. The frustrating thing about this process is that you can't control it; the ideas come in unexpected zigs and zags, and they're not delivered on demand. You can clear the way for them, though, by using the practices and techniques in this chapter. Successful creators are highly sensitive to their subconscious mind, and they've developed a deep awareness of how (and when) to listen to it. By practicing the discipline of play, you nurture your mind's natural ability to create. You put your conscious mind into a state in which it's wide open, it's listening closely, it's waiting for these ideas to emerge. The techniques in this chapter are simply ways to get all the logic and criticism and rules and inhibitions out of the way.

The Practices

Play seems so instinctive—and it actually was, when you were five. But for creative adults, play can be enhanced by mastering four practices: Visualize, Relax, Find the Right Box, and Be a Beginner.

The First Practice of Playing: Visualize

Visualizing is really just imagining possible futures. The techniques of this practice teach you how to imagine freely, the way kids do when they create fantasy worlds with blocks or dolls—and the way MacArthur geniuses do when they create scientific theories, great works of art, or new business models.

Imagine Parallel Worlds

Imagine Parallel Worlds

Pick one of the parallel worlds listed in the box. Now take whatever situation or problem you're puzzling over at the moment and try to envision it in that world's context. Or, try to think of ideas, images, or principles from that world that might be relevant to your problem.

- Deer hunting

- Motorcycle customization

- Vegan cooking

- Prison

- Dentistry

- Lawn care

- Hairstyling

- Foreign affairs

- Air travel

- Furniture design

- The Catholic church

- Comics

- The Mafia

- The Olympics

- The circus

- Vacation resorts

- Alternative medicine

One of my workshop students had been asked to create an oncology program that would be useful to Medicaid members. She chose furniture design as her alternate universe, and then she created this analogy: the frame of a sofa is like the bones of a body, and the fabric upholstery is like the skin, and the cushions are like the muscle tissue. For the sofa to be well designed, its structure has to be sound, its fabric has to look good, and its cushions have to be comfortable. That gave her three criteria by which to evaluate her program: structure, appearance and packaging, and user-friendly comfort and ease.

Come Up with Fantastic Explanations

Come Up with Fantastic Explanations

Stretch your imagination by using this technique whenever you find yourself relaxing outdoors, whether you're camping in the mountains or just stretched out in a hammock on a balmy summer afternoon. Clear away any practical worries or to-do checklists. Empty your brain. Absorb the air, gaze at the sky. Now think of a natural phenomenon that's a mystery to you, and come up with three wild and crazy stories to explain it. Your explanation should be obviously false, yet seem strangely plausible. I'll get you started with a first fantastic explanation for each:

- What causes disease?

1. Evil spirits enter your body.2. _____3. _____

- Why is the sky blue?

1. It's actually a big lake surrounding the earth.2. _____3. _____

- Why does it snow?

1. Snow comes from a giant salt shaker, and an extraterrestrial monster is about to eat the entire planet.2. _____3. _____

It might help to imagine that you're a Stone Age human trying to figure out these natural phenomena without the benefit of modern science. Or that you're a three-year-old.

Envision What's Below

Envision What's Below

What's underneath you right now? Ceramic tile sprinkled with a few crumbs from the dog's Milk-Bone, okay. But what's underneath that? Keep drilling, right down to the center of the earth.

If you're outside of a city, you may live in a freestanding house, and below the floor might be just the earth. I live in a former coal-mining region where there's a good chance an abandoned mine is down there somewhere. I can envision some used Styrofoam coffee cups, empty chewing tobacco tins, some dirty bandanas that got left behind, maybe a few coins that dropped out of a miner's pocket.

If you're in a city, there will be many layers of stuff underneath you—especially if you're not on the ground floor of a building. Underground, there are likely to be tunnels for utilities, and possibly subway tunnels. Let your mind wander; the more details you can envision, the better.

Follow the Long Arrow

Follow the Long Arrow

Wherever you're sitting, envision a straight, invisible arrow shooting horizontally away from you. Imagine that it keeps going for at least a kilometer or a mile, parallel to the ground. Imagine moving out along that line, very slowly. As you go, identify all of the objects you pass through.

You're likely to be indoors while you're reading this, and if so, the first thing your arrow will hit is the wall. Move very slowly through the wallboard to the inside of the wall. Is there insulation? Wiring? In a minute you'll reach the wallboard on the other side of the wall and enter another room. Eventually you'll be outdoors. As your arrow continues, what's the next thing it hits?

Take your time—your arrow flies very slowly. Make sure to imagine everything it will pass through. At the end of a mile, envision exactly where your arrow is when it drops to the ground. What's around the arrow? Where is it resting, on what kind of ground? What do you hear and smell and see?

Explore the Future

Explore the Future

Travel five years into the future, and imagine that you've succeeded beyond your wildest dreams. What is your life like as a result? How has your success changed your circumstances? Write down as many details about this world as you can think of (using the present tense). Then write an imagined history of what's happened in the previous five years. Pretend you're working for a newspaper or a magazine and you're writing an article describing these events. Be sure to talk about the important decisions made five years ago (that is, today) that made the success possible.

Or imagine that you're being interviewed by a reporter who's writing a story about your success, and she's asking you the following questions (you might prefer to speak your answers into a voice recorder instead of writing them down):

- What's the best thing about achieving your goal?

- Why did you choose to pursue this goal?

- What was the first step you took to move toward it?

- Can you talk about one early obstacle, and how you got past it?

- Did anyone help you along the way?

- What advice would you give to someone with the same goal who is just starting out?

Visualize Your Space

Visualize Your Space

Close your eyes and imagine the place where you work. Spend some time looking around in your mind: visualize all of the furniture, what's hanging on the walls, the objects sitting on the desk. Imagine yourself walking around and touching the furniture, the walls, the objects. Identify a few things that irritate you. In my office, with piles of books on the floor, I'd probably imagine tripping over them!

Now, with your eyes still closed, adapt the image. Change anything you'd like to make it better. Money is no object. Rules don't exist.

The Second Practice of Playing: Relax

The point of this practice is to step back and allow your mind to wander. These moments of distance and unfocusing are important; they give your mind some space, which it can then fill with new ideas.

The techniques in this practice help you develop enough trust and patience to let your subconscious work. You have to give it plenty of time to operate at its own pace, and then be alert when it's ready to deliver.

Incubate

Incubate

Creative people work harder than most other people—especially when they're engaged in the second step, learn. But, paradoxically, they also take more time off. That's because they know they have their best ideas when they're not working. People who work 365 days a year and never take a vacation rarely realize their creative potential. (Remember John Reed on the beach?)

There's no creativity without some slack time. This is one of the most solid findings of creativity research.

Let incubation work its magic.

Relax.

Alas, this technique doesn't work very well if you're under a deadline; you can't force incubation. But trust in the creative process; ideas will come soon enough. The key is what you do while you're relaxing. Don't just snack and watch TV. Do something that engages your mind and body in a way that's totally different from your focused work time. Physical activity is particularly effective: your conscious mind focuses on the movement, freeing up the space your subconscious needs to sneak new ideas into awareness. Go out for coffee; take a walk; exercise; work in the garden; wash your car; repair an appliance.

Seymour Cray, the legendary designer of supercomputers, had an odd hobby: he spent countless hours digging an underground tunnel leading from the basement of his house in Chippewa Falls. Why? “I work for three hours and then get stumped,” he explained. “So I quit and go to work in the tunnel. It takes me an hour or so to dig four inches and put in boards… Then I go up [to my lab] and work some more.”

Unrelated, gently busy activities foster incubation because they keep you from thinking about your problem, puzzle, or challenge. Your mind has a chance to wander, and you get into a relaxed state in which your conscious mind pulls back a little, slackening the reins. Instead of tension, there's a little play, a little give.

Most of these soothingly distracting activities aren't possible at work. So if you need a creative insight on the job, save a few mindless organizational tasks for such moments, or offer to clean out the break room fridge. Think of some way to create an incubation space at your office. (If your workplace culture says you have to “stay at your desk” and “always make sure you look busy,” you're probably not in a creative environment. Maybe you can change it. If not, you might need to find sanctuary someplace else: at a nearby coffeehouse, or sitting on a bench on the landscaped grounds, or in a new job …).

- In the tub

- On the treadmill

- Gardening

- Mowing the lawn

- Sorting the recycling

- Waiting in the doctor's office

- Shopping

- Listening to talk show radio

- Listening to a boring lecture

- Sitting through a boring meeting

- Commuting to and from work

Leave Something Undone

Leave Something Undone

At the end of the day, don't try to finish the task completely. Leave a little bit unfinished. Then, the next morning, you'll find it easy to get started.

This technique is based on psychological studies that show that when you leave a task undone, “cognitive threads” are left dangling in your mind. (Remember the failure indices from the last chapter?) Before you start work again the next day, all of your nonwork activities—fixing and eating dinner, reading or watching television, getting ready for bed, sleeping, waking up, and showering—expose your mind to a broad variety of unrelated perceptions. If you're lucky, these unrelated perceptions will somehow hook on one of those hanging cognitive threads, and you'll have a sudden insight.

This is why there are so many stories of people having an inspiration during their morning shower, or when waking up in the middle of the night.

Still Your Mind

Still Your Mind

Many people find that quiet time enhances their imagination and creativity. The key is to find a place where your mind can be quiet and your imagination can flourish.

Different people do this in different ways. For most people, this is a time for solitude. You might have a special chair, or a mat on the floor on which you can sit in the morning sun. Other people find that their imagination flourishes in the social activity and the buzz of a local coffeehouse.

- It's away from the place where you do most of the conscious hard work.

- It's safe, familiar, and comfortable.

- There is no task or work visible.

- You are not rushed, and you're not going to be interrupted (no e-mail, no phone).

Some people find it easier to still their thoughts when their body is moving. The ancient practice of t'ai chi is described as “meditation in motion” because its slow, graceful gestures silence the mind so effectively. Sometimes a workbench in the garage, or an easel on the back porch, creates a place to meditate. Taking a long walk is a time-honored way to clear your head. Or consider getting a dog; the necessary daily walks are perfect, regular breaks for meditative thought.

Listen

Listen

Even if you're reading this book in a fairly quiet place, there will be sounds around you—no place is completely quiet. Stop for a moment. Close your eyes. Breathe slowly and quietly. Listen to the everyday sounds you normally tune out:

- The clock ticking

- The fan of your computer or your home's furnace

- The sound of a truck driving by outside

The Third Practice of Playing: Find the Right Box

There's a popular belief that creativity comes from the absence of constraints. People assume that if you're not creative, it's because you're thinking inside the box—so all you need to do is get rid of the box!

But research shows just the opposite: creativity is enhanced by constraints. They just have to be the right constraints. The techniques of this section show you how important it is to draw boundaries around the space in which you play. If you're stumped for an idea, maybe you just need to play with different toys for a while; start a new game, with a different set of rules.

Be Specific

Be Specific

List as many white things as you can. Try to think of objects like chalk that are white by definition, not objects like cars or shirts that are only occasionally white.

_____

Now, list as many white, edible things as you can.

_____

The surprise for most people is that this second list is usually as long as the first! Why didn't you think of all of those items in the first part of the exercise? It's because more specific instructions result in greater creativity than do vague, open-ended instructions.

Beginning improv actors are taught to be specific when they propose new dramatic ideas. Instead of saying, “Look, it's a gun!” it's better to say, “Oh my god, it's the X-300 destroyer ray gun!” The second version makes it easier for your partner on stage to come up with a more creative reply. That seems counterintuitive, because the first version leaves your partner with a lot more options. But it works every time.

Draw the Right Box

Draw the Right Box

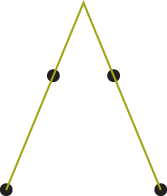

Connect the four dots shown here by drawing two connected, straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper between the first and second line. (Hint: You can't do it unless you draw outside of the trapezoid that's formed by connecting the dots.)

Turn to the next page for the solution.

The solution is an inverted V, with the lines extending above the top dots.

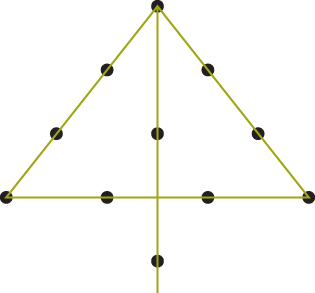

Now, see if you can connect these dots by drawing four connected straight lines, without lifting your pencil from the paper. (Hint: In this one, just like before, you'll have to go outside the dots.)

If you haven't gotten it yet, the next page helps you out by giving you the first line. Stay with me here; there's a reason to continue doing each exercise.

Give yourself a minute to think about it before turning to the next page for the answer.

Now, connect the four dots that follow by adding two more lines, starting at either end of the first line that's already drawn.

(Hint: Both lines have to go outside the box to make this work. If you're still stumped, the answer is at the bottom of this page.)2

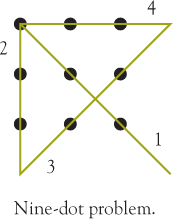

Now, that was all just practice. Here's a problem that should give you a bit more of a challenge. Connect these nine dots by drawing four connected lines without lifting your pencil:

Of course, you could use the three-line zig zag solution on the cover of this book, if you imagine the dots as marbles, or if you draw a very thick line—with a fat crayon, for example. And that's definitely a creative solution! But with small dots and a normal pencil, you'll need four lines.

If you haven't gotten it after a minute, look at the hint at the bottom of this page. (The solution is at the end of this chapter.)3

Without the proper training, the nine-dot problem is extremely hard; hardly anyone can solve it. The nine-dot problem is usually called an “insight” problem, because it's supposed to require a flash of creative insight to figure out that “you have to go outside the box.” In fact, the cliché started with this classic puzzle.

But the solution is not about thinking outside the box; it's about finding the right box. Now that you've solved similar problems, it's a lot easier. You don't need a blinding flash of insight, because you already know how to solve “outside the dots” problems.

After all that practice, you're now a pro. Are you ready for the sixteen-dot problem?

Without lifting your pencil, draw six straight lines that connect all sixteen dots. (Hint: Every line must go outside the box. The solution is at the end of this chapter.)

Create a New Box

Create a New Box

Invent your own tiny area, or box, of expertise, one that takes you only an hour or two to master. Some examples:

- Buy a motorcycle magazine and tear out all of the advertisements for protective clothing. Look through them closely and watch for the common features. Now you're an expert in “how to lay out motorcycle magazine ads.”

- Photograph the same scene with every possible setting on your camera. Now you've attained an expertise most camera owners never acquire: you understand how different settings change the image.

- Watch every YouTube video on how to tie a bow tie or a scarf. Now you can teach your kids.

- Go out in the yard. Pull up twenty blades of grass and take them inside. Carefully split each blade of grass in half, lengthwise. In ten minutes, you're an expert in “how to split blades of grass.”

- The next time you're in a diner, or any restaurant that has those napkin dispensers on the table, open up the dispenser and take out all of the napkins. Figure out how the spring works to make sure the napkins always stay right at the opening. In five minutes, you're an expert in napkin dispenser mechanics.

Successful creators are playful and inquisitive. When you live your life with a playful attitude, you develop an instinct to spend five minutes here and there mastering tiny boxes—just like children at play learn everything about how marbles roll on different carpet textures, or how a Slinky travels down the stairs. Before you know it, you're an expert in hundreds of tiny boxes. And that's when good things start to happen unexpectedly—because good ideas come from blending lots of different tiny boxes.

Use Every Box

Use Every Box

Which of the following letters is different?

Most people will say F because it's the only consonant. But every one of these five letters is different in a different way. Look at each letter in turn, and find something that makes it different from the others.

The Fourth Practice of Playing: Be a Beginner

Zen Buddhists have beginner's minds; gamblers have beginner's luck. And anyone trying to be creative needs to begin all over again every day so ideas will be fresh.

We start over again reluctantly; beginning is hard. It's so much easier to just recycle a solution that worked the last time. But beginning is exciting, too; everything is new, and all things are possible.

The techniques of this practice nudge you into the childlike state of not knowing. As you try each technique, notice how that beginner's mind-set feels, and try to take its wide-open innocence back to your own area of expertise. Become a beginner again and again.

Do Something for the First Time

Do Something for the First Time

When was the last time you did something for the first time?

Try …

- Hula-Hooping

- Juggling

- Playing harmonica

- Baking bread

- Building a card tower

Start a New Hobby

Start a New Hobby

Experiment with a new hobby. It can be something classic:

- Model trains

- Wood carving

- Basket weaving

Or you could try something new, such as

- Starting a blog

- Building a Web site

- Uploading a video to YouTube

- Making a video by editing footage from your last family holiday

Plan on Fun

Plan on Fun

Keep a written list of fun activities that you'd like to do someday. You could …

- Take cooking classes

- Go skydiving

- Race a motorcycle

- Sign up for a writing workshop

- Take piano lessons

- Learn archery

Add to the list as you hear about new opportunities and develop new interests. Resolve to do something from the list at least once each year.

Onward …

We've gotten through the first four steps, and I haven't said anything about how to have creative ideas! And yet these first four steps are the secret to a successful, creative life. When you engage in these four steps, your mind becomes a creative engine, generating ideas nonstop.

So now we're ready for the fifth step, think, generating creative ideas. You can't jump ahead to the fifth step; you won't have truly creative ideas without first going through these four steps. But now that you've made it to this point, you're ready for techniques to increase your brain's productivity.

Solutions

1 South Dakota

2 The two lines form a V that extends down beneath the bottom two dots.

3 You have to go outside the box two times.