Social Word of Mouth Marketing (sWOM)

Figure 1.1 An example of social sharing on Twitter

Source: Courtesy of C. Munoz.

Too personal? A tweet can say a lot. And a tweet with a hashtag and an image not only communicates more but is also much more likely to be shared. The screenshot in Figure 1.1 embodies many topics that this book will explore: the role of storytelling, the persuasive power of images, emotional appeals, personalization, and social sharing. It also marks the beginning of a positive story—which is where all good social media campaigns (and books) should begin.

In the summer of 2014, Coca-Cola launched the personalized “Share a Coke” campaign in the United States. Twenty oz. bottles of Coca-Cola, Diet Coke, and Coke Zero were adorned with 250 of the most popular American names for millennials and teens. Consumers were prompted to share their photos of the personalized bottles using #Shareacoke on social media. They could visit shareacoke.com to create and share virtual, personalized bottles on Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter. They could also be featured on Coke billboards by using #Shareacoke (Hitz 2014). Consumers were drawn to soda bottles that were emblazoned with not only their name but also the names of their family and friends. Coca-Cola’s bottle personalization was putting into action something that Dale Carnegie taught us long before—“A person’s name is to that person, the sweetest, most important sound in any language.” So, naturally, consumers wanted to share their name discovery on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Over the course of the campaign, consumers shared their experiences via the #Shareacoke hashtag over 250,000 times (Deye 2015). During the 2014 campaign cycle, more than 353,000 bottles were disseminated virtually (Tadena 2014). Geo-tagging and sales were correlated, and sure enough, there was a significant relationship between social sharing and sales (Deye 2015). By all accounts, the initial campaign was a sales success; Coke saw sales growth of more than 30 percent in one week (Deye 2015). Further evidence of the campaign’s success can also be found in its variations. In 2016, Coca-Cola launched “Share a Coke and a Song” which included song lyrics on labels, and in 2017, they printed holiday destinations on bottles distributed in the UK. More recently and with a focus on the COVID-19 pandemic, Coco-Cola created the “Holiday Heroes” Share a Coke campaign. Approximately, 40 heroes, such as caregiver, educator, and doctor, were placed on Coke labels (Arthur 2020). Today (or at least in 2022) you can still customize and purchase an 8 oz. Coca-Cola glass bottle for $6.00 (Coca-Cola 2022). Personalization is at the heart of why the Share a Coke campaign worked; however, part of their success was certainly attributed to the power of social word of mouth (sWOM) marketing.

93 percent of global consumers trust brand recommendations from family and friends more than any other forms of advertising. (Austin 2020)

Why Word of Mouth Marketing?

You are reading this book because you get it. Word of mouth (WOM) marketing is powerful—it impacts not only product preferences and purchasing decisions, but it serves to mold consumer expectations and even postpurchase product attitudes (Kimmel and Kitchen 2014). The beauty of branded WOM marketing communication is that it is a natural, normal part of our everyday conversations. In fact, over 2.4 billion conversations each day involve brands (Google; KellerFay Group 2016). The ample number of conversations related to products and services is attributable to the fact that we need and actively seek out input from family, friends, and even virtual strangers before we make a purchase. A 2021 study found that 98 percent of consumers surveyed believed that reviews were an “essential resource when making purchase decisions” (Power Reviews 2021). One of the reasons that family and friends’ recommendations matter so much is that they are simply trusted more—92 percent of consumers worldwide trust recommendations from family and friends more than any other type of advertising (Nielsen 2012; Austin 2020).

Marketing executives (64 percent surveyed) agree that WOM marketing is the most effective type of marketing (Whitler 2014). Further evidence of the effectiveness and popularity of WOM marketing can be found in the growing influencer marketing industry. In fact, influencer marketing spending is predicted to be over $37 billion in 2024 (ANA 2020). Outside of an implicit understanding that people seem to prefer the opinions of others over a TV advertisement, billboard, or branded website, on what information are marketers basing these beliefs? Can we quantify the effect of WOM?

In 2014, WOMMA (now merged with the Association of National Advertisers (ANA)) along with six major brands commissioned a study to determine the return on investment (ROI) on WOM marketing (WOMMA 2014). This was the first major study addressing not only the differing category impact of WOM but also its role in the overall marketing mix. Not surprisingly, the results reinforce many established beliefs about WOM’s level of importance.

• $6 trillion of annual consumer spending is driven by word of mouth (i.e., on an average 13 percent of consumer sales).

• WOM’s impact on sales is greater for products that consumers are more involved with (i.e., more expensive, higher risk).

• Most of the impact of WOM (two-thirds) is through offline conversations, whereas one-third is through online WOM.

• WOM, directly and indirectly, impacts business performance. For example, it can drive traffic to website or search engines, which can then impact performance measures.

• WOM can amplify paid media (e.g., advertising) by as much as 15 percent. The value of one offline WOM impression can be 5–200 times more effective than a paid advertising impression.

• Two weeks after exposure, online WOM (85–95 percent) has a quicker impact than offline WOM (65–80 percent) and traditional media—TV (30–60 percent).

Are these numbers compelling enough?

If you were paying attention, you would have noticed that according to these statistics, offline WOM appears to matter much more. Wharton Professor and author of Contagious, Jonah Berger, also suggests that we are spending too much time and effort on looking at online WOM (Berger 2013). Research supports Berger’s statement—a 2011 study from the Keller Fay Group found that only 7 percent of all brand-related WOM conversations occur online (Belicove 2011), with 94 percent of brand impressions happening offline (Google; KellerFay Group 2016). Berger suggests that this overestimation of online WOM occurs because we can easily see the conversation and we spend a lot of time online. And, we do spend a lot of time online; global online users spend approximately 7 hours per day online with roughly two-and-a-half hours spend on social media (We Are Social and Hootsuite 2022). In the United States, 85 percent of consumers are online every day, 48 percent are on the Internet multiple times a day, and 31 percent reporting an almost “constant” online presence (Perrin and Atske 2021). Without question, offline brand-related WOM matters more. But is online brand-related WOM limited to only 7 percent?

The truth is offline and online WOM are not like oil and water; they can and do mix. The WOMMA study illustrates that offline and online work together to, directly and indirectly, impact business performance. Consumers today move seamlessly between online and offline communication, making it increasingly difficult for us to pinpoint whether the message that we saw came to us in-person or via social media. And, the 7 percent?—that is, from a study completed in 2011 (aka 77 years ago in Internet dog years). To offer some perspective, in September 2011, Snapchat launched and Instagram only had 10 million users. Smartphone adoption of American adults was at 35 percent (Smith 2011). Things are different in 2022. Instagram now boasts approximately 1.5 billion registered users (We Are Social and Hootsuite 2022) and smartphone adoption is at 85 percent (Pew Research Center 2021).

Socializing online is seamlessly integrated into our offline lives. For today’s consumers, particularly those from a younger generation, there is no offline or online socializing, it is simply socializing. Even when we are supposedly offline, we are drawn back through a symphony of chirps and beeps alerting us to an online conversation we should be responding to. We are being normalized to believe that we should upload images of our food, family outings, and post about positive and negative consumer experiences. Consumer e-commerce websites, such as Amazon, are providing more opportunities for not only consumer comments but also allowing individuals to upload images and videos showcasing their recent purchase. Consumer feedback or input is essential in the purchase of the product. This feedback is becoming increasingly visual; take for instance, the online rental dress company—Rent the Runway. On the primary product screen for each dress, Rent the Runway shares photographs taken by their consumers wearing the rented dress. The company encourages consumers to review the dress and provide personal information such as their height, weight, bust, body type, age, size worn, usual size, and event occasion. For any one dress, there could be over 100 photos highlighting not only the fit but “how others wore it,” illustrating how to accessorize and wear one’s hair with the dress.

With the advent and ubiquity of smartphones, image and video creation is easy and uploading almost instantaneous. In 2020, it was estimated that 3.2 billion photos and 720,000 hours of video were produced and shared each day (Thomson, Angus, and Dootson 2020). And if we break this down to the minute (in 2020), TikTok users watch 167 million videos, Instagram users share 65,000 photos, YouTube users stream 694,000 hours, and 2 million Snapchats are sent (Domo 2021).

Marketers also seek to further blend online and offline worlds. Television and print ads are prompting consumers to go online and watch, follow, and like. Traditional televised news programs routinely integrate social media conversations and “what’s trending” segments. While old and new media continue to become more integrated, the line is also blurring between types of online media. Owned media (e.g., company website, blog), earned media (e.g., shares, reviews, reposts), and paid media (e.g., sponsored posts, ads) are becoming fused. For example, finance website The Penny Hoarder (owned media) pays guest bloggers (paid media). The Dallas Mavericks basketball team embeds its social media feed into its website (owned media) and utilizes hashtags #MFFL (Mavericks Fan For Life) to prompt others to post (earned media). Bath and bedding brand, Parachute, promotes the hashtag #MyParachuteHome for consumer content that includes the company’s products. They then use the social-shared, user-generated content (earned) to develop online ads and direct mail pieces (paid media) (Greenbaum 2020). In addition, Parachute has curated social media posts under the #myparachutehome heading within product landing pages. Consumers can click on a social media post to “shop the looks you love.” Other approaches that creatively blend earned and owned media are branded Snapchat lenses, Facebook filters, and TikTok branded effects. The OTC cold and flu medicine, Mucinex, created a contest asking TikTok users to dance like a zombie using the hashtag #BeatTheZombieFunk (apparently, we feel like Zombies when we have the cold and flu). Users could also use a branded effect on their videos—a dancing cartoon mascot, Mr. Mucus, superimposed over their video. This synergy of different media types paid off: over half a million videos were uploaded, the campaign had 5.8 billion views, and there was a 60.5 percentage lift in ad recall (TikTok 2022a). So, why are marketers exerting this level of interest in both shaping and spreading sWOM? You know the answer—many consumers are more likely to purchase a product after seeing it shared on social media via a friend or family member (Patton 2016). WOM marketing matters. So let’s explore it together.

Traditional WOM and Electronic WOM (eWOM)

Without question, WOM marketing is powerful and perhaps one of the most persuasive factors in the consumer decision-making process. The focus on WOM marketing has grown exponentially, and with it, related marketing constructs intended to increase its potency: influencers, referral programs, brand ambassadors, viral marketing, seeding campaigns, and brand communities (Kimmel and Kitchen 2014). A growing number of companies have been created to capitalize on the power and potential of WOM. But what exactly is it, and how does word of mouth extend to the Internet?

WOM marketing is not new—but instead, our appreciation, evolving technology, and the growing number of firms and resources devoted to the topic has changed. The WOMMA trade association defines WOM marketing as “any business action that earns a customer recommendation.” Academically, numerous definitions have been put forward that are typically more complicated than industry’s (see Kimmel and Kitchen 2013 for a review). For example, “word of mouth is the interpersonal communication between two or more individuals, such as members of a reference group or a customer and a salesperson” (Kim, Han, and Lee 2011, 276). Or “in a post-purchase context, consumer word-of-mouth transmissions consist of informal communications directed at other consumers about the ownership, usage or characteristics of particular goods and services and/or their sellers” (Westbrook 1987, 261). Both definitions focus on the activity or the result of the activity (Kimmel and Kitchen 2013). As some of these definitions indicate, WOM communication can be either instigated by consumers organically, or when marketers are involved, the messages become amplified. Organic WOM refers to when consumers, without being prompted by marketers, discuss their product experiences. Whereas amplified WOM refers to marketing efforts to encourage consumers to amplify the WOM. This can include reaching out to influentials to spread the word and carefully crafting messages so that consumers want to share them and that are easy to be shared, creating buzz, and using referral programs. Later in this chapter, we will argue that we need to give more attention to the third type of WOM communication—collaborative. Collaborative can be thought of as a combination of both organic and amplified—a message that is jointly created and shared by marketers and consumers who have an interest in a product.

On the surface, WOM appears to be simple. It involves the communicator, message, and receiver. However, the WOM process is impacted by a host of contributing factors. What are the attributes of the communicator—in particular, credibility? What motivates the communicator and receiver in creating or looking for the message? How much knowledge does the receiver have about the product? How important is the product to them? How strong is the connection between the communicator and the receiver? What is the message valence—positive, negative, or neutral? What is the mode and delivery of communication?

As you can see, it gets complicated. One of the more recent complexities is understanding whether or not what we know about traditional offline WOM translates to the Internet (eWOM)—is it “old wine in new bottles”? (Hint: it’s not).

eWOM

Over a decade ago, scholars sought to differentiate eWOM from traditional WOM, defining it as “any positive or negative statements made by potential, actual, or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet” (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004, 39). Unlike traditional WOM, which is communicated verbally, eWOM is transmitted through a variety of electronic communication channels: discussion boards, corporate websites, blogs, e-mails, chat rooms or instant messaging, social media, review websites, and newsgroups. There are numerous differences, outside of modality, between WOM and eWOM (Cheung and Thadani 2012; Chu and Kim 2011):

• The messenger/source: In traditional WOM, the receiver of the message is acquainted with the individual communicating it—the messenger or source. Even if the individual is somewhat of a stranger, there is a context and cues that will help discern the messenger’s credibility. In eWOM, the consumer may not be aquainted with the individual. This complicates the credibility of the message and the authenticity of the messenger.

• Many messengers and many receivers: In “real life,” WOM occurs as a one-on-one conversation between friends or in a small gathering, whereas eWOM can be akin to one individual (or many) screaming into a packed stadium full of people that is continually turning over with new spectators.

• Message/opinion transmitter: In traditional WOM, there is the opinion giver and receiver. However, eWOM provides a new role—that of the message or opinion transmitter. The transmitter may be the opinion giver, receiver, or someone new. As opposed to traditional WOM where distortion is likely to occur when and if the message is shared (think “game of telephone”), in eWOM, the message can be transmitted with a higher degree of accuracy.

• Limited privacy: WOM conversations occur in person typically between two individuals or in a small group. In contrast, eWOM messages can be shared immediately, repeatedly, and with 100 percent accuracy to the Internet world. Messages can be accessible to the masses.

• Asynchronous (not in real-time) communication: WOM communications are typically synchronous. eWOM is primarily asynchronous—conversation occurs over a period that, in some cases, can span years.

• Messages are enduring: Unlike face-to-face conversations, which quickly fade from our memories, online communication endures, sticking around long after that initial exchange.

• Measurable/observable: The Internet allows us to track, observe, and measure online conversations through various online analytic tools and measures (i.e., Constant Contact, Hootsuite). This simply is not possible (to this degree) in traditional WOM (yet).

• The speed of communication diffusion: eWOM can spread at an exponential speed. The conversation is not limited to water cooler banter but can spread across the globe in seconds. This is particularly true within social media.

• More communication with weak ties: Within an online environment, there is more exposure to what is known as “weak ties.” The term “weak ties” refers to “contacts with people where your relationship is based on superficial experiences or very few connections” (Tuten and Solomon 2015, 92). For example, a casual acquaintance or a friend of a friend. In traditional WOM communication, we frequently receive messages from friends and family (“strong ties”). While communication with “strong ties” certainly occurs online, there is more exposure and interaction with “weak ties”—strangers and online-only acquaintances. At least one study found that online weak ties were more persuasive than strong ties when selecting college courses and professors (Steffes and Burgee 2009).

sWOM Defined and Explained

When the Internet was first launched, electronic content was created by a few but consumed by the masses. Consumers could only read content; they could not create it (the Web 1.0 era). At the turn of the millennium, there was a gradual shift to create a Web where Internet users were not only consumers but also creators of Web content. The Web became a place where consumers could create, engage, and collaborate with each other (the Web 2.0 era). At first, electronic communication modalities consisted primarily of online discussion forums (e.g., Yahoo! Groups), boycott websites (e.g., walmartsucks.org), and the most popular of all, opinion websites (e.g., epinions.com) (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004). Now it includes a vast array of social platforms with varying degrees of media richness. But is WOM communication delivered via Facebook the same as those posted to a chat room or message sent via e-mail? Similarly, to the delineation of eWOM from traditional WOM, we believe that WOM communication via social media (sWOM) also deserves a more nuanced look. Specifically, we view social word of mouth (sWOM) as a subset of eWOM. We are not the first to propose reexamining and segmenting eWOM. Researchers Wang and Rodgers (2010) recognized the limitations of the earlier eWOM definition. They point out that conversations are not just positive or negative—many include mixed reviews and neutral information (Wang and Rodgers 2010). They also acknowledge the relationship between user-generated content (UGC) or consumer-generated content (CGC) (i.e., Internet content created and posted online by consumers) and eWOM, viewing eWOM as a type of UGC. Wang and Rodgers (2010) suggest that eWOM should be broken down further into two categories: informational-orientated contexts (i.e., online feedback systems and consumer review websites) and emotionally-oriented contexts (i.e., discussion boards and social networking sites). Both these typologies do not encompass all forms of electronic communication (i.e., e-mail and chat rooms or instant messaging).

In many respects, it almost sounds silly and redundant to call it sWOM. Yes, the essence of WOM is about being social. However, we argue that there is a distinct difference between WOM communication via social media and other eWOM tools, such as Instant Communication (IM) chat rooms, e-mail communication, review websites, and newsgroups.

• Personal accounts: In the case of eWOM, a large majority of information is shared on a company or third-party accounts. For example, a consumer writing a product review on Amazon, a concerned citizen posting a comment on a news website, or complaining about a malfunctioning product in a customer service forum. In contrast, a large percentage of sWOM is posted to and shared from a consumer’s personal account. The recipients of sWOM are more likely to be connected to the poster (strong or weak ties) than are the readers of posts that appear on the company or a third-party account. This fact alone may increase the credibility and persuasiveness of the message.

• Audience: When a consumer posts a comment to his or her personal social media account, it has the potential to be seen by a wider assortment of consumers. In contrast, eWOMs reach may be limited to those consumers who are interested in the topic or product being discussed. For example, product reviews on Amazon are seen only by those consumers viewing the product, whereas a larger audience may see a product review posted on Facebook. Granted a consumer’s Facebook friends may not have an interest in the product mentioned. However, the fact that they are exposed to the posting may have some level of influence at a later point in time.

• Defined messenger: Within social media, a user’s communication is connected to their profile. Profile information typically consists of an image and multiple descriptors. A descriptor can be as short as a sentence (e.g., Twitter) or as long as a resume (e.g., LinkedIn). E-mail, newsgroups, review websites, and chat rooms will typically only provide a user-name and user address. User descriptors are an important step in building credibility and trustworthiness in WOM communications.

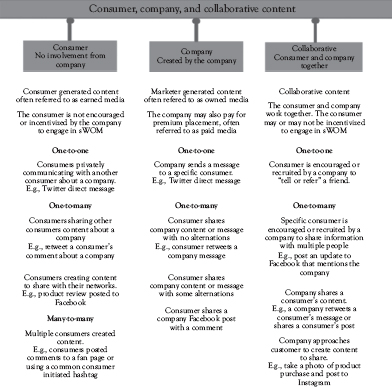

• Communication direction: Social media platforms allow for one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many forms of communication between the message communicator and receiver(s) (Figure 1.2). In other words, conversations can be between individuals (e.g., private direct messages on Twitter), one-to-many (e.g., tweet to a network), but also many-to-many, where a message is created and discussed within a network (e.g., tweet using a hashtag). sWOM encompasses three communication directions, whereas traditional WOM and eWOM are limited to one or two directions.

• Highly accessible and searchable: Unless a user has established privacy settings, social media posts can quickly be found through searches on social media platforms, major search engines, and specialized social media monitoring tools (e.g., Hootsuite, Meltwater). In contrast, chat rooms or IM and e-mail are not publicly searchable. It should also be noted that an increasing number of social media platforms are becoming synchronous and transient through the use of video and expiring content (i.e., Snapchat and Facebook Live).

• Faster scalability: Chat rooms or IM, e-mails, and newsgroups do not have the potential reach of various social media venues such as Twitter and Facebook. While an e-mail certainly has the potential to be sent far and wide, its dissemination does not match the speed and out-of-network connections that social media can. You also do not see entire TV shows and regular news segments devoted to trending e-mail.

• Saturated information overload: Many social media platforms (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) provide users with abundant information each time they log in. On social media, marketers face fierce competition for consumers’ attention (Daugherty and Hoffman 2014). To further complicate this issue, the active lifespan of a social media post can be very short, as it becomes buried in the sea of newly created content. On a website, a product review can live forever, but on social media, the life of a message can be fleeting. The median lifespan of a tweet is a matter of minutes, and a Facebook post will get the vast majority of its impressions in the first few hours after posting (Ayres 2016).

• Communication occurs in a mediated environment: Communication within social media occurs primarily through their social media platform. While many platforms (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) allow for direct communications via an internal mail system, the content that is shown or is more prominently displayed is readily controlled by the platform’s algorithm. Popular user posts and trending news and information, which can be commented upon, are not entirely under consumers’ control.

• More visual: Social media is becoming an increasingly visual medium. Facebook’s (now Meta’s) acquisition of Instagram, the ease with which you can incorporate images and video into a tweet, and the popularity of Pinterest, Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok all speak to consumers’ ability and desire to incorporate imagery into their communication. Older forms of electronic communication, such as e-mail, are not as visually oriented.

• Cocreation: Social media content is frequently cocreated between consumers and between marketers and consumers (and vice versa). This is often referred to as collaborative content. Marketers can inspire conversations or the creation and sharing of images through various initiatives such as contests and hashtag campaigns. Sometimes, these conversations generate a positive result, other times, consumers can, intentionally or unintentionally, take them in a negative direction. There are many examples of where hashtags have become “bashtags.” In 2014, the hashtag #myNYPD sought to encourage positive images of police officers and instead received, over one day, almost 102,000 tweets addressing various civil rights violations (Swann 2014). In some cases, marketers have also taken over existing consumer hashtags with negative consequences. In one example, Digiorno Pizza used the hashtag #WhyIStayed and included the answer—“I had Pizza.” Unfortunately, the hashtag was already associated with domestic violence (cringe!). Needless to say, they quickly deleted the message and profusely apologized but not before it received wide media attention (Griner 2014). More recently, companies have tried to capitalize on hashtag political movements by lending their support via social media. L’Oreal Paris, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, created an Instagram post with the message “Solidarity is worth it” along with a text description that included #BlackLivesMatter. The post was seen as disingenuous as L’Oreal Paris had previously fired the black model Munroe Bergdorf for speaking out about racial injustices. A social media backlash occurred, and L’Oreal ended up hiring Ms. Bergdorf as a Diversity and Inclusion consultant (Nesvig and Delgado 2020). There are, however, examples of positive consequences—DDB New York used the established #FirstWorldProblems meme for their highly successful WATERisLife viral video ad campaign. The campaign featured impoverished Haitians reading various “problems” (i.e., “I hate it when my house is so big, I need two wireless routers”) (Payne and Friedman 2012).

sWOM communication is any visual or textual post about a company or their product offering that is either created independently by a consumer, created by a company, or created by a consumer in collaboration with a company and publically shared on a personal or company social media account.

We define sWOM communication as any visual or textual post about a company or their product offering that is either created independently by a consumer, created by a company, or created by a consumer in collaboration with a company and publicly shared on a personal or company social media account. This definition is broader than other WOM or eWOM definitions; in that it considers not just opinions regarding the traditional products that a company sells but also the content that the company disseminates via social media. The stories that brands tell via social media are part of the product and contribute to its brand equity. This idea is similar to what consulting company McKinsey has called a “consequential” type of WOM marketing, “which occurs when consumers directly exposed to traditional marketing campaigns pass on messages about them or brands they publicize” (Bughin, Doogan, and Vetvik 2010). Social media has provided countless ways to distribute a wide variety of information that consumers deem valuable enough to share. Whether a social media post includes an e-book, white paper, product photography, how-to video, recipe, or even a joke, the act of sharing itself is an endorsement or recommendation. And, while a consumer may not be directly discussing the traditional product offerings of a company, they are still disseminating and conversing about a company’s offering in the form of their digital assets. This act of sharing in the social media space can be as simple as forwarding information (i.e., retweet or share), personalizing information that is created by someone else, writing product- or brand-related comments, or creating product- or brand-related content and posting it (i.e., video, photograph, etc.). The other aspect of this definition we need to highlight and explore is the intersection between consumers and companies in the social media environment (Figure 1.3). Increasingly, consumers and companies are cocreating content in both planned and organic ways.

As illustrated in Figure 1.3, sWOM communications can include one-to-one (e.g., direct message on Twitter), one-to-many (e.g., Facebook status update), or many-to-many (e.g., the use of a popular hashtag) messages. Communication can originate from a consumer, a company, or both parties can collaborate (the 3 Cs). Consumer content is created by a consumer without any involvement from a company—organic content. Examples include sharing an experience on Facebook, creating a video for YouTube, or Instagramming a photo of a recent purchase. This is commonly referred to as earned media because there is no cost to the company. Company-generated communication refers to the content created and posted by the company’s marketing department. The company shares this communication with one or more consumers in the hope that they will engage with the content through liking, sharing, retweeting, and commenting, thereby amplifying the communication. This is commonly referred to as paid media, particularly if the company has paid to promote the communication (e.g., promoted tweet). Outside of consumer-generated and company-generated content, there is a middle ground; a combination of both organic and amplified WOM efforts—collaborative. In this instance, consumers and companies are working together to create and share information. For example, a company may invite consumers to upload photos of their purchase with a hashtag. The Parachute example offered earlier in this chapter is an example of collaborative communications. Collaborative communication has seen significant growth in recent years, thanks in part to high smartphone-adoption rates (Tode 2015). Stores are now thoughtfully integrating social media within consumers’ in-store experience. Consumers are not only prompted via signage to not only “follow,” “like,” “Check-In,” and review retail venues but also to contribute to social media conversations via a preselected and promoted hashtag.

Some stores, like Target and Victoria Secret, even craft in-store photo-ops. See Figure 1.4 for an example. Both campaigns encourage users to take photos and use their hashtags (#targetdog, #vstease, #vsgift). Victoria Secret went a step further by rewarding their consumers with a “sexy surprise” (after they showed an associate that they shared their branded selfie). Signage is also becoming more dynamic as retail is slowly starting to embrace digital signage. Perhaps, displaying consumer tweets and posts related to brands will become commonplace within stores. Companies can create contests that require consumers to create content to be shared. Another example of collaboration communications is when companies hire social influencers to tweet positive statements about the company. Depending on the strategy, collaborative communication can be a combination of earned, paid, and owned media.

Regardless of whether the sWOM is consumer- or company-generated or whether it is a collaborative effort, some forms of sWOM require more effort than others. Retweeting takes much less effort than generating a new post. Generating a new status update takes less work than creating a video and posting it on YouTube. The amount of effort required of the consumer is closely tied to consumer engagement. The topic of engagement is covered in Chapter 2, so we will not discuss it here. But for now, suffice to say that marketers need to ensure that they account for varying levels of engagement and pay more attention to consumers participating in higher level engagement forms of sWOM.

Source: Courtesy of C. Munoz.

The importance of sWOM for marketers can be summarized in two key facts. First, almost everyone online uses a social network (Mander 2016). While usage rates may vary dramatically between consumer segments, social media is touching and impacting the lives of most consumers. Second, sWOM influences each stage in the consumer decision-making process and can impact sales. Like WOM and eWOM, sWOM serves as an important information source in the prepurchase research process. The Global Web Index Survey found that social media is used by 28 percent of Internet users to find “inspiration for things” and 27 percent find products to purchase. Social media was more popular in product-related searches for younger consumers (GWI 2021, 2022). Simply put, consumers are increasingly turning to social networks and consumer reviews to hear their friends’ (and strangers’) opinions on products, view pictures depicting how the product “really” looks, and find new uses and applications through videos. However, the extent to which they rely on social media in their investigations depends heavily on the type of product they are considering purchasing (Bughin 2015). Outside of facilitating product research, sWOM is leading to sales. In fact, there is evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only increased purchasing online but also that sWOM has been increasingly influential. A survey by Stackla found that 72 percent of consumer surveyed are spending more time online and 56 percent are more influenced by social media content since the start of the pandemic. Moreover, 79 percent indicated that user-generated social media content impacted their purchasing decisions, and 66 percent were “inspired” by other consumers’ social media images to purchase a new brand (Stackla 2021). Given the increasing rates of online shopping and the growing number of technologies that integrate shopping options directly into social media posts, it is not unreasonable to expect that sWOM’s direct sales influence will continue to increase.

Outside of being instrumental in product research and influencing sales, sWOM communication has other benefits. Let’s look at some examples of how sWOM communication has made a difference:

• Generate awareness or buzz: Hershey’s Cookies “N” Crème created a TikTok Gen Z-focused campaign running In-Feed Ads drawn from four popular creator accounts. The four creators also posted short videos from their personal TikTok accounts. Ultimately, TikTok videos were successful in creating brand awareness (13 million video views and a 32.8 percent lift in ad recall) (TikTok 2022b).

• Increase social media engagement: Popular WOM content via social media can quickly increase a brand’s engagement, likes, or the number of followers on social media. Cadbury decided to honor (and elicit engagement) from their nearly one million fans of their UK Facebook page by creating a giant Facebook “like” thumb out of Cadbury milk chocolate. The result was over 40,000 new Facebook likes (in two days) and an increase of 35 percent for active fans (Bazu 2013).

• Inspire new product ideas and resurrect old ones: There is truth to TED Talk’s slogan—“Ideas Worth Spreading.” Good ideas catch on, and smart marketers look to popular sWOM messages for product inspiration. Popular organically created hashtags such as #BringBackCrystalPepsi helped inspire Pepsi to re-release this 1990s clear soda in 2016 (Mitchell 2015; PepsiCo 2016). Whereas other companies ask consumers directly to come up with new product ideas. Take, for instance, Lay’s “Do Us a Flavor” contest, which asked consumers to come up with new potato chip flavors and encouraged fans to vote via social media. The flavor winner received $1 million, and consumers’ taste buds were treated to exotic flavors such as Crispy Taco (2017), Southern Biscuits and Gravy (2015), Wasabi Ginger (2014), and Cheesy Garlic Bread (2013) (PepsiCo 2017).

• Increase consumer satisfaction: It goes without saying that you need to monitor social media conversations about your brand. Companies such as Nike and JetBlue go a step further by having dedicated Twitter handles to address consumer comments and questions. This has allowed them to provide, especially in the case of JetBlue, real-time support and frankly, happiness. Take, for instance, the story of a JetBlue customer who tweeted that he would board his 100th flight with them that year. Without knowing his name or flight (but looking up his handle and then tracking him down), they met him at his arrival gate with a banner and cupcakes (Kolowich 2014). Heck, we would have been satisfied with a retweet!

• Raise awareness and money for nonprofit causes: A growing number of nonprofits have been using sWOM to increase awareness for their cause and inspire donations. Facebook (now Meta) created its first platform fundraising tool in 2016. As of March 2021, Facebook and Instagram fundraising tools have raised over $5 billion in donations to nonprofits and some personal causes (Meta 2021). Many of these fundraisers are birthday fundraisers. Notable nonprofit fundraisers include the ALS association raising over $5 million St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital was gifted over $100 million, and No Kid Hungry has been able to help feed kids 100 million more meals (Gleit 2019).

Our Journey Ahead

This book is not an introductory “how-to” book on social media. It is assuming that you have already gotten your feet wet (or drenched) in the topic. Instead, the purpose of this book is to examine the influence of sWOM and provide guidance on how to operationalize its growing power. Our goal in writing this book is to bring together industry best practices and academic research to illustrate how much sWOM matters. It should also help you construct social media posts that will be both shared and conform to regulatory guidelines. Each chapter highlights a key area of sWOM that will further your understanding of the topic and provide actionable information to increase the likelihood of creating your own sharable sWOM marketing successes:

The Social Consumer

The social consumer examines individuals who use social media to inform their product decisions and also share product-related information and opinions with others. This chapter explores who they are, the different roles they play, and their motivations to share. It concludes what an acknowledgment that consumers are rethinking how they should integrate social media in their lives.

The Social Business

In most companies, social media usage begins in the marketing department, but it should not end there. Social media can add value in other ways including, offering strategic insights, identifying problems, crowd-sourcing ideas for new products and services, improving customer service, recruiting new employees, and empowering employees to spread positive sWOM. In this chapter, we discuss the importance of becoming a social business. We review the stages of social business development and how social tools can be integrated to become part of your company’s DNA.

Storytelling

Social media posts need to tell a story and marketers need to learn to be good storytellers. This chapter explores how to construct shareable stories concentrating on not only textual content but also the importance of visual communication in all your marketing efforts.

Social Influencers and Employee Advocates

Influencer marketing has seen tremendous growth in recent years. Influencers are no longer just celebrities. In fact, companies can see more return on their investment by utilizing “everyday consumers” or even their employees. This chapter provides an overview of the different influencer types, how to select an influencer that is right for a brand, and how to implement an influencer campaign. Particular attention is also given on creating and operationalizing an employee influencer advocate program.

The Power of Persuasion

To be successful in social media and to encourage sWOM, your company needs to be influential. In this chapter, we explore six principles of persuasion as they apply to social media.

Legal and Regulatory Issues

There is a very fine line between encouraging and incentivizing consumers and employees to engage in sWOM about your brand—a line that may have legal implications for your company. In this chapter, we examine “material connections”—relationships that exist between a company and an endorser of your brand—and the guidelines that must be followed to ensure that consumers are not being deceived by information they learn and recommendations they receive on social media. This chapter also explores the importance of having a well-developed social media policy, the process of creating a policy and appropriate content.

References

ANA. 2020. “The State of Influence: Challenges and Opportunities in Influencer Marketing.” Retrieved from www.ana.net/miccontent/show/id/rr-2020-state-of-influence.

Arthur, R. December 2, 2020. “Coca-Cola Dedicates Share a Coke to ‘everyday hereos’.” Beverage Daily. Retrieved from www.beveragedaily.com/Article/2020/12/02/Coca-Cola-marks-pandemic-year-by-dedicating-Share-a-Coke-to-everyday-heroes.

Austin, S. November 3, 2020. “Why Trust and Incentives Help Consumers With Better Brand Selection.” Entrepreneur. Retrieved from www.entrepreneur.com/article/357871.

Ayres, S. 2016. “Shocking New Data About the Lifespan of Your Facebook Posts.” Post Planner. Retrieved from www.postplanner.com/lifespan-of-facebook-posts/ (accessed June 22, 2016).

Bazu, A. 2013. “Cadbury’s ‘Thanks a Million’ Campaign: The Sweet Taste of Success!” UCD Graduate Business School Blog. http://ucdblogs.ucd.ie/digitalmarketingstrategy/cadburys-thanks-million-campaign-sweet-taste-success/ (accessed February 08, 2017).

Belicove, M. November 2011. “Measuring Offline Vs. Online Word-of-Mouth Marketing.” Entrepreneur. Retrieved from www.entrepreneur.com/article/220776.

Berger, J. 2013. Contagious. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Bughin, J. 2015. “Getting a Sharper Picture of Social Media’s Influence.” McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/getting-a-sharper-picture-of-social-medias-influence.

Bughin, J., J. Doogan, and O. Vetvik. 2010. “A New Way to Measure Word-of-Mouth Marketing.” McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/a-new-way-to-measure-word-of-mouth-marketing.

Cheung, C.M.K. and D.R. Thadani. 2012. “The Impact of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication: A Literature Analysis and Integrative Model.” Decision Support Systems 54, no. 1, pp. 461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.008.

Chu, S.C. and Y. Kim. 2011. “Determinants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-of-Mouth (eWOM) in Social Networking Sites.” International Journal of Advertising 30, no. 1, pp. 47–75.

Coca-Cola. 2022. “Custom Bottles Page.” Coca-Cola. Retrieved from https://us.coca-cola.com/store/custom-bottles.

Daugherty, T. and E. Hoffman. 2014. “eWOM and the Importance of Capturing Consumer Attention Within Social Media.” Journal of Marketing Communications 20, no. 1–2, pp. 82–102. doi:10.1080/13527266.2013.79 7764.

Deye, J. 2015. “#ShareACoke and the Personalized Brand Experience.” Marketing Insights. Retrieved from www.ama.org/publications/eNewsletters/MarketinglnsightsNewsletter/Pages/shareacoke-and-the-personalized-brand-experience.aspx (accessed February 08, 2017).

Domo. 2020. “Data Never Sleeps 9.0.” Domo. Retrieved from www.domo.com/learn/infographic/data-never-sleeps-9.

Gleit, N. 2019. “People Raise Over $2 Billion for Causes on Facebook.” Meta for Business. Retrieved from https://about.fb.com/news/2019/09/2-billion-for-causes/.

Google; KellerFay Group. 2016. “Word of Mouth (WOM).” Retrieved from https://ssl.gstatic.com/think/docs/word-of-mouth-and-the-internet_infographics.pdf (accessed May 28, 2016).

Greenbaum, T. 2020. “7 User-Generated Content Examples and Why They Work So Well.” Retrieved from https://www.bazaarvoice.com/blog/7-ugc-examples/.

Griner, D. 2014. “DiGiorno Is Really, Really Sorry About Its Tweet Accidentally Making Light of Domestic Violence.” AdWeek. Retrieved from www.adweek.com/adfreak/digiorno-really-really-sorry-about-its-tweet-accidentally-making-light-domestic-violence-159998.

GWI. 2021. “Social Media Marketing in 2021.” Global WebIndex. Retrieved from www.gwi.com/reports/social-report-b.

GWI. 2022. “Social Media Use By Generation.” Global WebIndex. Retrieved from www.gwi.com/reports/social-media-across-generations.

Hennig-Thurau, T., K.P. Gwinner, G. Walsh, and D.D. Gremler. 2004. “Electronic Word-of-Mouth Via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet?” Journal of Interactive Marketing 18, no. 1, pp. 38–52. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/dir.10073.

Hitz, L. 2014. “Simply Summer Social Awards Contestant #3 | Simply Measured.” The Simply Measured Blog. http://simplymeasured.com/blog/simply-summer-social-awards-contestant-3-cocacolas-shareacoke-campaign/#sm.00018n9uis1172fifrc4xqq28xm0f (accessed February 08, 2017).

Kim, W.G., J.S. Han, and E. Lee. 2011. “Effects of Relationship Marketing on Repeat Purchase and Word of Mouth.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 25, no. 3, pp. 272–288. doi:10.1177/109634800102500303.

Kimmel, A.J. and P.J. Kitchen. 2013. “WOM and Social Media: Presaging Future Directions for Research and Practice.” Journal of Marketing Communications 20, no. 1–2, pp. 1–16. doi:10.1080/13527266.2013.797730.

Kimmel, A.J. and P.J. Kitchen. 2014. “Introduction: Word of Mouth and Social Media.” Journal of Marketing Communications 20, no. 1–2, p. 24. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc11&NEWS=N&AN=2013-45151-002.

Kolowich, L. 2014. “Delighting People in 140 Characters: An Inside Look at JetBlue’s Customer Service Success.” Hubspot Blog. Retrieved from http://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/jetblue-customer-service-twitter#sm.00018n9uis1172fifrc4xqq28xm0f.

Mander, J. 2016. “97% Visiting Social Networks.” GlobalWebIndex. www.globalwebindex.net/blog/97-visiting-social-networks.

Meta. 2021. “Coming Together to Raise $5 Billion on Facebook and Instagram.” Meta for Business. Retrieved from www.facebook.com/business/news/coming-together-to-raise-5-billion-on-facebook-and-instagram.

Mitchell, E. 2015. “Pepsi Makes the Most of Viral #BringBackCrystal Pepsi Campaign.” Adweek. Retrieved from www.adweek.com/performance-marketing/pepsi-makes-the-most-of-viral-bringbackcrystalpepsi-campaign/.

Nesvig, K. and S. Delgado. June 09, 2020. “Munroe Bergdorf Joins L’Oreal Paris as Consultant After Calling Out the Brand.” TeenVogue. Retrieved from www.teenvogue.com/story/munroe-bergdorf-loreal-paris-black-lives-matter.

Nielsen. 2012. “Newswire | Consumer Trust in Online, Social and Mobile Advertising Grows.” Nielsen. www.nielsen.com/insights/2012/consumer-trust-in-online-social-and-mobile-advertising-grows/#:~:text=According%20to%20Nielsen’s%20latest%20Global,an%20increase%20of%2018%20percent.

Patton, T. 2016. “8 Statistics That Will Change the Way You Think About Referral Marketing.” Ambassador Blog.

Payne, E. and C. Friedman. 2012. “Viral Ad Campaign Hits #FirstWorld Problems.” CNN. Retrieved from www.cnn.com/2012/10/23/tech/ad-campaign-twist/.

PepsiCo. 2016. “Celebrate the 90s With Crystal Pepsi—Iconic Clear Cola to Hit Shelves This Summer.” PepsiCo Press Release. www.pepsico.com/live/pressrelease/celebrate-the-90s-with-crystal-pepsi-iconic-clear-cola-to-hit-shelves-this-su06292016.

PepsiCo. 2017. “America Has Voted! Lay’s Crispy Taco Crowned 2017 Lay’s Do Us a Flavor.” Pepsico. Retrieved from www.pepsico.com/news/press-release/america-has-voted-lays-crispy-taco-crowned-2017-lays-do-us-a-flavor-winner10112017 (accessed February 08, 2017).

Perrin, A. and S. Atske. 2021. “About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Say They Are ‘Almost Constantly’ Online.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved from www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/26/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-say-they-are-almost-constantly-online/.

Pew Research Center. 2021. “Mobile Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved from www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

Power Reviews. 2021. “New Consumer Survey of More Than 6,500 Consumer Reveals Increasing Importance of Product Reviews to Establish Trust and Drive Purchase Behavior.” GlobeNewswire. Retrieved from www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/05/20/2233533/0/en/New-Consumer-Survey-of-More-than-6-500-Consumers-Reveals-Increasing-Importance-of-Product-Reviews-to-Establish-Trust-and-Drive-Purchase-Behavior.html.

Smith, A. 2011. “Smartphone Adoption and Usage.” Retrieved from www.pewinternet.org/2011/07/11/smartphone-adoption-and-usage/.

Stackla. 2021. “Post-Pandemic Shifts in Consumer Shopping Habits: Authenticity, Personalization and the Power of UGC.” Stackla. Retrieved from https://stackla.com/resources/reports/post-pandemic-shifts-in-consumer-shopping-habits-authenticity-personalization-and-the-power-of-ugc/.

Steffes, E.M. and L.E. Burgee. 2009. “Social Ties and Online Word of Mouth.” Internet Research 19, no. 1, pp. 42–59.

Swann, P. 2014. “NYPD Blues: When a Hashtag Becomes a Bashtag.” Public Relations Society of America. www.prsa.org/Intelligence/TheStrategist/Articles/view/10711/1096/NYPD_Blues_When_a_Hashtag_Becomes_a_Bashtag#.V3PeIvkrKM8 (accessed February 08, 2017).

Tadena, N. July 15, 2014. “Coke’s Personalized Marketing Campaign Gains Online Buzz—CMO Today—WSJ.” The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/cmo/2014/07/15/cokes-personalized-marketing-campaign-gains-online-buzz/.

Thomson, T.J., D. Angus, and P. Dootson. 2020. “3.2 Billion Images and 720,000 Hours of Video Are Shared Online Daily. Can You Sort Real From Fake?” The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/3-2-billion-images-and-720-000-hours-of-video-are-shared-online-daily-can-you-sort-real-from-fake-148630.

TikTok. 2022a. “Mucinex.” TikTok for Business. Retrieved from www.tiktok.com/business/en/inspiration/mucinex-98.

TikTok. 2022b. “Hershey’s Cookies ‘n’ Crème.” TikTok for Business. Retrieved from https://us.tiktok.com/business/en-US/inspiration/hershey’s-cookies-‘n’-cr%C3%A8me-365.

Tode, C. August 10, 2015. “Retailers Adapt Social Media for Real-World, In-Store Sales Impact.” Mobile Commerce Daily. Retrieved from www.mobilecommercedaily.com/retailers-adapt-social-media-for-real-world-in-store-sales-impact.

Tuten, T. and M.R. Solomon. 2015. Social Media Marketing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wang, Y. and S. Rodgers. 2010. “Electronic Word of Mouth and Consumer Generated Content: From Concept to Application.” In Handbook of Research on Digital Media and Advertising: User Generated Content Consumption, ed. M. Eastin, pp. 212–231. New York, NY: Information Science Reference. doi:10.4018/978-1-60566-792-8.ch011.

We Are Social and Hootsuite. 2022. “Digital 2022 Global Overview Report.” Retrieved from https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2022/01/digital-2022-another-year-of-bumper-growth-2/.

Westbrook, R.A. 1987. “Product/Consumption-Based Affective Responses and Postpurchase Processes.” Journal of Marketing Research 24, pp. 258–271. doi:10.2307/3151636.

Whitler, K. 2014. “Why Word of Mouth Marketing Is the Most Important Social

Media.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/kimberlywhitler/2014/07/17/why-word-of-mouth-marketing-is-the-most-important-social-media/#3443d9c37a77.

WOMMA. 2014. “Return on Word of Mouth.” Retrieved from https://womma.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/STUDY-WOMMA-Return-on-WOM-Executive-Summary.pdf (accessed February 08, 2017).