Stay Out of the Net

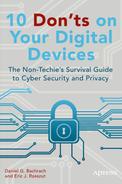

Joe is a midlevel procurement manager with 14 years of experience at the multinational company Worldwide, Inc. His section is a large one, and much of the procedural updating that regularly comes through official channels is disseminated virtually—by text, the corporate instant messaging application, or e-mail. Joe rarely sees his immediate supervisor during the course of an average day and is accustomed to getting—and following—electronically delivered policy and housekeeping directives. Joe’s communications with administrators from other sections in his division also typically come through company e-mail. From time to time updates to the company’s IT systems require him to change his existing passwords or create new ones, so he is not uneasy when he receives a routine e-mail from his company’s IT group directing him to update his system password (see Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. Sample e-mail asking for password confirmation and featuring two hyperlinks: the company logo and the “Update your account info” line

The e-mail is fairly well-written and looks kosher. It employs quasi-proper English grammar, incorporates the company logo in the usual way, and is signed with the correct phone extension for the IT help desk. The message contains a hyperlink to the company’s web site and another for Joe to confirm his existing password and set a new one.

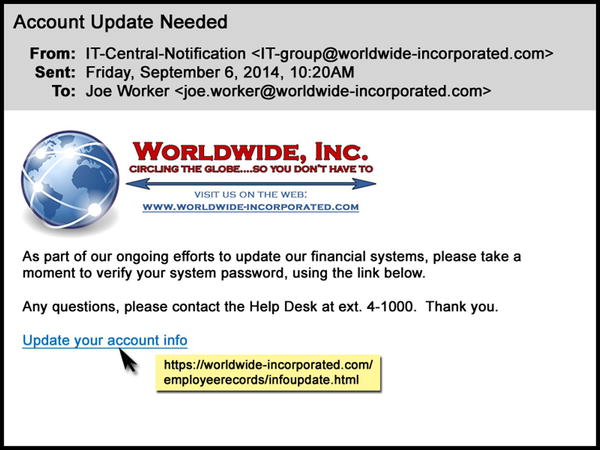

Joe nearly clicks the second link but hesitates when he remembers that upcoming system password changes are announced at the weekly section meeting and that he can’t recall such an announcement having been made at the last one. He hovers his cursor over the hyperlink and is alarmed to see that it would take him not to his company’s domain (Figure 1-2) but to a malicious domain (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1-2. Joe hovers his cursor over the account update hyperlink, expecting it to give his company’s domain name, as shown

Figure 1-3. Joe instead sees that the hyperlink would take him to a malicious domain

A Closer Look at “Phishing”

“Phishing” is a virtual attack that uses a more or less compelling or attractive lure to acquire confidential or proprietary information through the use of fraudulent electronic communication. Victims of phishing attacks get caught when they take the bait offered by a phisher, such as an apparently legitimate request by their IT department to change a password or by their credit card company to protect an account with an additional personal information gate. E-mail is the most commonly used approach to launch a phishing attack, but such attacks can also be launched through web sites, text messages, IM (instant messaging), and mobile apps. Phishing techniques began to be deployed in the late 1980s, some years before the term itself was coined. The term derives from “fishing” for gullible users’ login credentials and personal details, orthographically tweaked by substituting f with ph by analogy with “phreaking” (the practice of cracking phone network security to make free long-distance calls). The phish most commonly seen by IT departments is the one that almost snared Joe in the opening scenario. An electronic communication is sent to a target with a link embedded in a message that looks official but in reality originates from a fraudulent party seeking to steal personal information in order to gain malicious access or to resell to a criminal cyber organization.

Phishing techniques are increasingly sophisticated and well-crafted. No longer are incongruous language, improbable scenarios, or misaligned layouts used that give off the stink of phish that is immediately obvious to any employee. Today, the word choice, spelling, and grammar deployed in the most dangerous class of phishing messages are correct or, even better, are calibrated to be just slightly illiterate, in the same way that genuine corporate communications tend to be (as in Figure 1-1). Such phishes blend company logos, colors, design schemes, and other attributes of official communications in mimicry of legitimate messages that employees and customers routinely receive. Their sending e-mail addresses and hyperlink URLs are typically “spoofed” to resemble those of legitimate senders.

Sophisticated phishing operations are adept at securing and exploiting information about companies’ internal changeover periods. If a company is in the process of undergoing IT system changes of any kind, its users are more likely to expect rather than suspect password change requests and other change-associated e-mails. Phishers prefer to time their attacks to correspond with periods of transition when users’ psychological defenses are temporarily relaxed.

The majority of phishing attacks are long-line or net phishing. These attempts don’t have a specific target. Their goal is to snare as many victims as possible following a volume or economies-of-scale approach and leveraging a broad, randomized targeting scheme. Contrasted with this kind of broadcast phishing is spearphishing, which is carefully and lethally aimed at a specific individual, company, school, or other organization. These kinds of attacks are much more dangerous than conventional untargeted phishing scams.

“Target”-ed Phishing

A targeted spearphishing attack may be deployed to go after someone specific, such as Joe, because the attackers are aware that he has a system account with access to sensitive company information. A general, untargeted phishing attack may go out to literally tens or hundreds of thousands of mailboxes or phones. If even a few of the targets click on the malicious link, the attack is a success. Spearphishing attacks, on the other hand, target a defined group of users or even only one high-value user within an organization.

One of the troubling characteristics of contemporary phishing is the range and versatility of tactics attackers use to lure or lull victims into providing valuable information. For example, in phone-keypad phishing, users are told to dial a number that a caller says belongs to the end user’s bank or credit-card company but that is in reality owned by phishers. End users enter their account number, social security number, PIN code, or other private information via the telephone keypad, which is then captured and sold or used by the phishers.

Phishers use cross-site scripting (CSS or XSS) to compromise legitimate sites with pop-up windows or browser tabs that redirect users to fraudulent web sites. CSS attacks are more prevalent on computers and systems with unpatched and/or outdated operating systems (for more, see Chapter 8).

Neutralizing phishing is not a trivial issue. What’s at stake? Money. Most phishers are in it purely for financial gain. EMC’s 2013 annual report estimated that $5.9 billion was lost worldwide to nearly 450,000 phishing attacks. This same report identified a hacking tool called Jigsaw that allows malicious actors to gain specific and detailed employee information for use in spearfishing attacks. With access to your bank account information and password, phishers can easily transfer funds away from your accounts or divert a paycheck or other direct deposit away from your account to accounts that they control.

Phishing also increases personal and organizational exposure to malware. For example, in November 2013 malware called Zeus was spread via attachments to phishing e-mails that claimed to contain important system and security updates. Once installed on a PC, Zeus detects banking, credit card, and other financial information entered by the end user and reports those credentials back to a compromised server. Reputable antivirus manufacturers such as Sophos and Norton issued statements immediately reminding users that no legitimate software manufacturer would ever send out security updates by e-mail attachment. Within a short time all the commonly used anti-malware programs, such as Microsoft Security Essentials and Sophos Antivirus, added specific protections against the Zeus malware to their security definitions. The users most at risk from malware are those who neglect to use continually updated anti-malware software.

But, it’s important to recognize that criminal phishers don’t limit themselves to attacks on little phish. Sometimes, they target and land the big phish as well—sometimes the whale. The well-publicized attack on Target Corporation that evolved over the course of several weeks during November and December of 2013 was likely instigated through a phishing attack on a Target contractor. In this massive security breach, more than 10 million Target customers’ credit card numbers were stolen. A heating, air-conditioning, and refrigeration firm headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Fazio Mechanical, reported a phishing attack on its systems. This attack was responsible for the delivery of a password-stealing piece of malware called “Citadel” that ultimately was the mechanism used to breach and compromise Target’s systems.

The malware attack at Fazio Mechanical is believed to have begun two months before the Target Corporation was, well, targeted. In addition to suffering a massively expensive public relations black eye, Target also directly shoulders some of the technical/operational responsibility for the loss of customers’ credit card information. Target failed to properly segregate its information systems infrastructure broadly—and its customer credit card databases specifically—from virtual corridors connecting directly to outside contractors. An HVAC contractor simply shouldn't have access to Target Corporation’s customer credit card data! But this breach, which turned out to have been one of the largest in U.S. history, was most likely catalyzed directly by an employee at Fazio who was tricked into clicking a link that just shouldn't have been clicked. Big storms start with small breezes…

Other Forms

Criminal phishing attacks aren’t limited to an approach through e-mail. For example, SMS phishing or “smishing” is a similar kind of attack, but one that is executed through the use of text messaging to potential victims’ mobile phones. Users receive a text message that their bank, credit card company, or other financial institution (credit union, student-loan company, etc.) needs them to reconfirm some aspect of their on-file personal information for records updating. This request could include anything from a user’s social security number to his mother’s maiden name to the specifics of the checking account used to pay monthly invoices. Absolutely no topic is off-limits.

On a similar tack, voice phishing is called “vishing.” With vishing, attackers use automated voice systems with which they can impersonate a bank or other robocaller. We’re all familiar with these calls today, getting them regularly from financial institutions or other sources, reminding us of appointments, of an upcoming event, or of changes in policy. Vishers can also often “spoof” the caller ID on the targeted victim’s phone, making it seem as though the call actually originates from a legitimate organization—even one from the user’s own contact list.

Criminals today are extremely flexible in the approaches they adopt. They take advantage of a wide range of common vehicles to camouflage their activities. Some of these are fairly new, so most users today haven’t developed the kind of healthy caution they might otherwise have when interacting with a more familiar potential delivery mechanism for malware. With QRishing, criminals play on our familiarity with—and excitement about—the now ubiquitous QR bar codes used in advertisements, on cereal boxes, and on a host of other products we see every day. Unfortunately, this particular convenience is as susceptible to parasitical encroachment as other modern vehicles. A QR code may say, for example, “Scan this to win a prize,” while in reality it installs a piece of malware directly onto your phone or computer.

And, of course, social networks are not immune from these kinds of attacks. Phishing scams are extremely common on Facebook and Twitter. “Click here to win free airline tickets.” “Click this for free games.” Phishers will use embedded links in communications masquerading as content coming from your friends, your work, your place of worship—any source you might trust—all with the goal of enticing you to click.

As we discuss in depth in Chapter 9, these are all types of “social engineering” approaches that attackers use to prey on our human nature to achieve their goals. They’ll use the threat of lost or found money (“You'll be charged $5/day unless you click here” or “You can win $1,000!”), authority (“Your supervisor requests that you enter your password here”), or immediacy (“There’s an emergency and we need your information immediately!”). Nothing is too devious or out of bounds, no message too sensitive, no concern too sacred.

Adopting a slightly different bearing, “USB-ishing” is an approach that attackers use to lure potential victims into plugging an unknown USB flash drive into their computer. Attackers will leave attractive, high-capacity drives in conference rooms, rest rooms, hotel lobbies, or other public places where they are likely to be found by unsuspecting phish. When a user connects the flash drive to a computer, the USB drive then automatically installs a Trojan, a key logger, or other malware onto the user’s machine—most often without the user knowing it’s been delivered.

This particular point of vulnerability may also have a broader, underlying structural problem. In July of 2014, security researchers Karsten Nohl and Jakob Lell demonstrated that USB drives are inherently unsafe by design. At the Black Hat security conference, these researchers demonstrated that malware can actually be hidden in the firmware of a USB device—the very software that controls the device itself. By concealing malware in the physical artifact in this way, it is undetectable by modern anti-malware software. Even more troubling here, the malware stored in firmware in this way is not removed when the drive is erased and or reformatted.1 Because USB flash drives are so incredibly useful, and because most of us use them every day for even our most sensitive data, the results from this report are chilling. Any USB drive that has ever been out of our direct control is vulnerable. What’s becoming increasingly clear is that the very fine line between security and usability continues to get thinner and thinner every day!

What Should You Do?

To avoid the potentially grave personal and financial costs of falling prey to phishing, like Joe, develop habits of reflexive suspicion and jealously guard your personal data. Unattractive traits in face-to-face situations are virtues online and can help to keep you safe (or at least safer).

Your suspicions should be raised if you receive an unsolicited e-mail or IM, click on a web site, or receive a phone call that asks for any of the following types of highly sensitive information:

- Your password

- Your bank account information

- Your employee ID or social security number

- Other private data

You should never provide any of these sensitive data via e-mail. E-mail is inherently insecure—there is no such thing as a private e-mail. This basic operational fact of virtual exchanges in the 21st century means that no legitimate organizational representative would ever ask you to provide this kind of information via e-mail.

Over the phone or on a web site, caution is no less essential. If you have any doubts about the legitimacy of a caller or a web site, make contact using a familiar, established, and assuredly valid channel, such as the phone number or the web site printed on the back of your credit card. Look closely at any e mails that claim to come from your bank, credit card company, mortgage company, or employer. Be suspicious. Are the colors in the logo a tad off or is the overall look not quite right? Are there any oddities of expression, slovenly spellings, or grammatical hiccups?

If you are ever asked in an e-mail to click a link, study it with gimlet eyes. Hover your mouse pointer over the link to see where it is going to take you before you click. Phishers rely on end users to be too hurried or distracted to notice clues that would emerge on closer inspection.

Look at the end of the web address—not the beginning or the middle—to see if it’s truly the site that it purports to be. If you click the link and go to the page, evaluate the page using the same criteria as you would when evaluating a suspicious e-mail. Look critically at the logo, colors, spelling, grammar, and vocabulary for any signals that something is awry. If it is, go no further. You could be putting your sensitive personal and professional data at risk—and putting your company’s servers and all of their systems in jeopardy as well.

Unless you’re perfectly confident an e-mail or web site is legitimate, don’t enter any data. If you’re working for a firm with an IT department, get in contact with your section IT supervisor. If you are on your own, seek out and ask a reputable source about the e-mail or the web site. If it’s your credit card company, bank, or other financial institution, call the phone number on the back of your card or on your billing statement to determine whether the contact is legitimate or not.

If you’re at all suspicious about an e-mail, do not reply to it. If you reply to a phishing e-mail with questions seeing clarification, the phishers will just lie to you and tell you whatever they think you want to hear. You represent no more than a criminal mark to them. E-mail is simply not a secure method of communication for any kind of critical information. E-mails can be hacked or intentionally or accidentally forwarded to others; anyone with an official purpose is wary of these inherent limitations.

It is important to forward suspicious e-mail to your IT supervisor, if you work for a firm with an IT group. The IT consultants can confirm whether or not the e-mail you received is a phishing e-mail. They can also often block or otherwise prevent that particular sender from reaching any of the computers or systems at your company again. If you realize only after clicking a link and entering personal data that it’s suspect, you should immediately take the following steps.

First, change all passwords and other identifiers that you provided to the suspect site. This will stop or retard phishers’ efforts to make direct use of your data. If you entered work-related data, notify your immediate supervisor and the IT area supervisor at once. It is essential that the right sequence of remedial protections be initiated to try to limit the spread of damage. If you entered personal credentials or financial data in reference to your bank account or credit card company, notify those companies immediately. When cleaning up a phishy mess, it is especially important to use channels that are above suspicion, such as calling the phone number on the back of your card or on your statement or visiting your local bank branch in person. The crucial and inviolable rule is to never to send passwords or other private data via e-mail.

Although it’s out of the hands of the “average user,” e-mail providers also are doing what they can to intercept phishing attacks before they reach users’ in-boxes. In August of 2014, Google announced that it would be implementing new anti-phishing mechanisms for its enormously popular e-mail service, Gmail. Google will now restrict the use of Unicode characters—characters in non-Latin alphabets, or alternates to Latin characters—when used in certain combinations designed to trick people. For example, replacing the letter a in “OnlineBank.com” with a Greek lower-case alpha wouldn’t be noticeable to most end users (see Figure 1-4). But with the proliferation of international web domains that allow non-Latin characters, the user could unknowingly be taken to an entirely different web site.2

Figure 1-4. Most users would never notice (or understand the significance of) the difference in these two URLs. The top link is typed in standard Latin characters; the second link replaces the lowercase a with a Greek lowercase alpha

Be cautious and take steps to protect yourself from non-e-mail forms of phishing. Be suspicious of unsolicited text messages and phone calls. Be careful when scanning any QR codes. Use common sense when looking at links on your social networks, links that purport to be from your “friends.” If something seems too good to be true, it probably is! When in doubt, contact your friend via a known-to-be-good method (e-mail, phone, text) and ask if she sent you a particular link. Don't use USB flash drives that you find somewhere or that are handed out, and be cautious when lending USB drives to someone else (and then getting them back). On all of your social network sites, always watch your links!

Additional Reading

For more reading on how to keep away from phishers and their bait, see the following links, and visit our web site at www.10donts.com/phished.

- Microsoft Safety & Security Center, “How to Recognize Phishing Email Messages, Links, or Phone Calls,” with examples of these various types: www.microsoft.com/security/online-privacy/phishing-symptoms.aspx

- Norton Security, “Spear Phishing: Scam, Not Sport,” featuring a discussion of how spearphishers attempt to gain information on their targets: http://us.norton.com/spear-phishing-scam-not-sport/article

- OnGuardOnline (produced by the US Department of Justice), “Phishing Scams,” which includes methods for reporting phishing attackers: www.onguardonline.gov/phishing

- PayPal, “Can You Spot Phishing?”, a quiz that tests the reader’s knowledge of common and uncommon phishing attack vectors: www.paypal.com/webapps/mpp/security/antiphishing-canyouspotphishing

- Sophos.com, “Simple Steps to Avoid Being Phished,” www.sophos.com/en-us/security-news-trends/bestpractices/phishing.aspx

- Stay Safe Online (powered by the National Cyber Security Alliance), “Spam and Phishing,” with some good general advice: www.staysafeonline.org/stay-safe-online/keep-a-clean-machine/spam-and-phishing

______________________________

1Wired, Andy Greenburg, “Why the Security of USB Is Fundamentally Broken,” www.wired.com/2014/07/usb-security/, July 31, 2014.

2Google Official Enterprise Blog, Mark Risher, “Protecting Gmail in a Global World,” http://googleenterprise.blogspot.com/2014/08/protecting-gmail-in-global-world.html, August 12, 2014.