Don’t Let the Snoops In

Keep Your Personal Data Personal…

Maria is an attorney who specializes in issues of privacy. She advises clients on the application of encryption methods, secure transmission of data, data protection overseas, etc. She counsels corporate clients on their rights concerning information and data related to disgruntled or terminated employees, and company rights bearing on examination of employee-used laptops and other devices. On corporate-owned devices, including phones and tablets, users can have absolutely no expectation of privacy. The firm can monitor and track all employee communications—work-related and personal—and look at all of their data at will. Because of Maria’s expertise in this area, her friends and family come to her with their personal privacy concerns as well. Her friends hear about current scandals and stories in the news, such as the recent Edward Snowden case, about search engines like DuckDuckGo and browsers like Tor, and ask Maria’s professional opinion of these events. Although she advises them to maintain their privacy to as great an extent as possible, she also admits that the open nature of the Internet is mechanically somewhat antithetical to the maintenance of total privacy.

Maria has had many spirited discussions with her friends and family about the practice of what has come to be called “targeted advertising.” Targeting is a tactic encompassing a set of tracking methods that commercial firms use to determine end users’ search patterns and browsing history. These data are used to select and present ads coinciding with preferences for related products and services. Maria’s opinion is that if you have to see ads on the Internet anyway, they might as well be relevant. Many of her friends disagree. They find the practice “creepy” and “Big Brother-ish,” but Maria sees preference matching more as being consistent with the nature of the Internet in the 21st century. Information about us is everywhere.

When educated, professional, up-to-date consumers today hear the words “snoops” or “spies,” they are most likely to think of government encroachment on privacy and civil liberties. In the United States we tend to think in terms of the most famous (or perhaps infamous) “three-letter agencies”: the NSA (National Security Agency), FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), and CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). Other countries have very similar agencies pursuing national security agendas, such as the GCHQ in the United Kingdom and the Mossad in Israel. In the United States, since 2001, it’s become increasingly evident that the NSA in particular has extremely broad access to a great deal of personal and financial data on ordinary American citizens.

This agency has access to data from our phone calls, text messages, e-mails, web site visits, social media posts, etc. Such data include not only information at the “to whom the call was made” or “from whom an e-mail was received” level, known as metadata, but content-related data as well—deep, personal content. The NSA “mines” the data and then subjects them to profound analysis using mathematical algorithms and artificial intelligence to uncover underlying patterns. These patterns are used to elicit usable information on people who may be involved with terrorist groups or other suspect organizations. The legality of this kind of data mining, often focused on citizens who have neither been accused nor convicted of a crime, without a specific court warrant, has been and continues to be hotly debated in courtrooms in the United States, United Kingdom, and around the world. An in-depth discussion of the legal issues bearing on this topic is well outside the scope of this book. Nonetheless, the accumulation, analysis, and application of personal data by governmental entities are raising serious civil liberties concerns that are likely to have far-reaching policy implications once the dust begins to settle on these questions. As of now, these implications are unclear.

The legality of governments spying on their own citizens is in doubt and calls into question a wide range of deeply held beliefs reflective of our identity as citizens in the Land of the Free, but of course countries do not limit their “snooping” activities to their own citizens. In 2013 the French newspaper Le Monde released a damning report accusing the NSA of collecting the telephone conversations and text messages of over 70 million French citizens. Caitlin Hayden, then spokeswoman for the National Security Council, responded: “The United States gathers foreign intelligence of the type gathered by all nations. We’ve begun to review the way that we gather intelligence, so that we properly balance the legitimate security concerns of our citizens and allies with the privacy concerns that all people share.” This doesn’t all go one way—it works in the other direction too. In May 2014, a US grand jury indicted five Chinese military officers, charging them with espionage and cyber crimes related to attacks at six US corporations. The Chinese government, which maintains no formal extradition policy with the United States, has flatly refused to hand over these officials to face trial.

Of course, on everyone’s radar is the highly electric case of Edward Snowden, which has generated an enormous level of media attention on the issues of privacy and government snooping. A former NSA contractor, Snowden released thousands of classified documents to the media in June 2013, fled to Russia, and was granted asylum in August 2013. The documents leaked by Snowden revealed the existence of many ominous US and worldwide surveillance programs.

These programs include the following:

- Boundless Informant

- PRISM

- Tempora

- MUSCULAR

- FASCIA

- Dishfire

- Optic Nerve

Let’s take a closer look at them now.

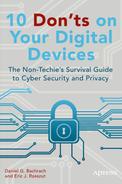

This is a big data mining and analysis tool used by the NSA. The documents leaked by Snowden included a “heat map” (shown in Figure 6-1) depicting the density of the NSA’s relative surveillance levels worldwide. Writing for the Wire, columnist Philip Bump estimated that this program gathered 9.7 petabytes of information (equal to 970,000 gigabytes) in a single month.1

Figure 6-1. This “heat map,” part of the NSA’s Boundless Informant program, shows the relative levels of surveillance performed on countries worldwide. Countries in green have relatively few surveillance actions, while countries in yellow, orange, and red, are more closely watched. (Public domain image, prepared by a US government official.)

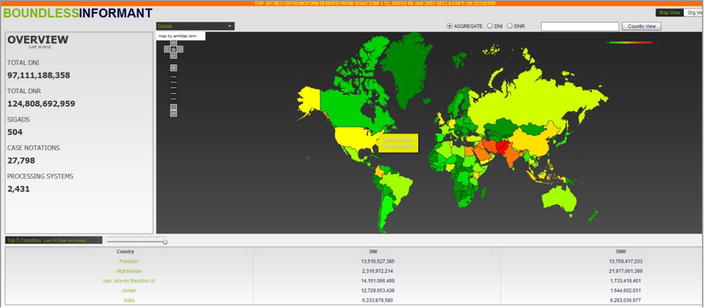

This is an electronic surveillance program started by the NSA in 2007 that gathers stored e-mails and other Internet communications from companies like Google, Verizon, and Yahoo!. This program takes advantage of the fact that much of the world’s Internet communication passes through servers in the United States (see Figure 6-2), even when neither sender nor recipient are physically in the United States.

Figure 6-2. A presentation slide from the NSA’s PRISM surveillance program shows how data may be captured from servers inside the United States, even when the destination and recipient are in other countries. (Public domain image, prepared by a US government official.)

Tempora is a British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) surveillance program whose data are regularly shared with the US government. This program uses secret taps on the fiber-optic backbone cables that undergird the Internet.

MUSCULAR is a joint US/UK program designed to access e-mail, documents, and mapping data from Google and Yahoo! (see Figure 6-3). Documents released by Snowden claimed that the MUSCULAR program had accessed millions of records at Google and Yahoo!.

Figure 6-3. Documents released by Edward Snowden claimed that the MUSCULAR program had accessed large amounts of customer data at Google and Yahoo! by exploiting the servers connecting these companies’ private networks to the public Internet. According to the Washington Post, “Two engineers with close ties to Google exploded in profanity when they saw [this] drawing.”2 (Public domain image, prepared by a US government official.)

This is an NSA database that collects geolocation data (i.e., physical location) from cell phones, tablets, laptops, and other electronic devices.

Dishfire is a second joint US/UK program designed to collect text messages from users worldwide, analyzing them using an algorithm-driven tool called Prefer.

This is a GCHQ program developed in conjunction with the NSA that collects webcam still-images from users without their knowledge. This program was first publicly disclosed in February 2014. Documents released by Snowden indicate that the program was active from 2008 until at least 2012. The Snowden documents revealed that users were viewed from their own webcams and were “unselected,” or randomly chosen. An ACLU statement offered that “This is a truly shocking revelation that underscores the importance of the debate on privacy now taking place and the reforms being considered. In a world in which there is no technological barrier to pervasive surveillance, the scope of the government’s surveillance activities must be decided by the public, not secretive spy agencies interpreting secret legal authorities.”

So, Who Else Is Snooping?

The NSA, FBI, CIA, and other “three-letter agencies” definitely receive the most press attention when it comes to invasions of personal privacy and Internet eavesdropping. Snooping, however, is in no way limited to governments monitoring our telephone conversations or cataloging our text messages. Other agencies and groups have a vested (financial) interest in collecting as much data as they can about end users’ Internet activities, and, critical here, it may not be in those users’ best interest to allow this kind of access to their private activities.

For-profit corporations are very interested in you—and your money—and want to know what you spend your time searching for online. If you are looking at products manufactured or sold by a competitor, businesses want to know about it. They want to display advertisements relevant to your online searches, with the goal of helping you to realize that their products or services are better and that you should purchase from them rather than the competition.

Consistent with the online omnipresence theme, in June 2014 the social media giant Facebook announced that it would begin tracking users’ browsing habits outside of Facebook.com or the mobile Facebook app. If users are logged in to Facebook while browsing other sites online, Facebook would use those search data to guide its display of ads to coincide with the content of users’ online activity. “The thing that we have heard from people is that they want more targeted advertising,” said Brian Boland, Facebook’s vice president in charge of ads product marketing. “The goal is to make it clear to people why they saw the ad.”3 Market research firm Qriously, in a recent study commissioned by the Wall Street Journal’s CMO Today, reported that the privacy question may simply be a matter of semantics. Qriously announced that 54 percent of the respondents in their research said that they preferred “relevant” ads to “irrelevant” ads. The preferences of “Maria” from the beginning of the chapter may be among the majority. Yet, in the same survey, only 48 percent preferred “targeted” ads to “non-targeted” ads. Here, “relevant” and “targeted” are actually the same concept phrased differently. Users apparently don’t likely to feel “targeted,” even if they are!4

Although the government serves at the discretion of the people, theoretically, and for-profit organizations exist only as a consequence of market whimsy, most of us work for employers who do have legitimate claims on where we go and how we spend our time online. Employers have a vested interest in keeping track of what their employees do when they are using company equipment. Equipment can include computers, tablets, smartphones, company wireless networks, and any other infrastructure that supports employees’ online activities. The rights of employers to essentially unfettered access to all of our data and information have been upheld in a wide range of contexts. In the United States, courts have consistently ruled that employees have no “expectation of privacy” in the workplace.5,6

In light of this access, it is critical that employers maintain a comprehensive acceptable use policy (AUP) for company IT resources, with the penalties associated with violations of the policy clearly articulated. It is more critical that employees follow these policies!

Given the increasingly flimsy boundaries separating personal from work spaces, these policies may carry over into employees’ personally owned devices. This kind of restriction/penalty carryover is most likely when employees’ own equipment is used to access work resources or to connect to company networks. The main issue in focus throughout this book is control over the loss or theft of data. Employees often are compelled by AUPs to report the theft or loss of any electronic device—whether it be their company’s or their own—used to access company resources. Failure to report this kind of loss can be significant. Broad-scale compromise of virtual infrastructure, the loss or theft of clients’ personal data, competitor access to trade secrets, and even employment termination are potential consequences of noncompliance. It also is now extremely common practice among many larger firms to require the use of a pass-code or PIN on employees’ personal mobile devices before connection to corporate e-mail servers is permitted.

![]() Note This requirement, and its benefits, will be discussed further in Chapter 7.

Note This requirement, and its benefits, will be discussed further in Chapter 7.

Where Your Data Are…

Keeping the snoops out of your data involves different kinds of approaches depending on whether the focus is “data at rest” or “data in transit.” Data at rest refers to data stored on any one of a user’s personal devices, such as photos, tax documents, or work-related spreadsheets on a hard drive, the flash memory in a phone or tablet, etc. Those same data often need to be sent to, or are received from, someone else as work-related materials are forwarded for a meeting or pictures sent to a family member; they then become “data in transit.”

Data on the Move

When your data are on the move, there are some steps that can be taken to protect them on your own device(s). But users have to rely on third-party providers or employers to protect these data in transit. For example, end users can take advantage of products such as PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) to digitally sign their e-mails. If PGP is used then e-mails can be read only if the recipient has a “key” to access them. This key can be provided over the phone or through other non-e-mail methods. However, both using and configuring PGP is technically complex. Likely as a result of this complexity it has not seen widespread adoption. Somewhat famously, journalist Glenn Greenwald nearly lost his chance to initiate contact with Edward Snowden because he couldn’t get PGP correctly configured.7

In June 2014 Google announced that it had begun testing a plug-in for its Chrome browser. When used in conjunction with Gmail services this “end-to-end” plug-in is intended to make the e-mail encryption/decryption process much simpler for end users. This is likely to increase its visibility over more complex options, including PGP. Other similar encryption programs, such as “miniLock,” are starting to appear in the marketplace, focused on a wider, nontechnical audience.

In addition to e-mail, many people also adopt cloud services to move their data. While most of these services claim some level of encryption of customers’ data in transit (diminishing the probability that third-party attackers can gain access to it), many also reserve the right to inspect users’ data or provide access to these data to authorities if requested. However, providers’ dependence on governmental license to engage in interstate commerce increases the complexity of their relationship with your data as it pertains to issues of privacy.

For example, in 2012 Microsoft suspended the accounts of a SkyDrive (now OneDrive) customer because he had uploaded data that violated terms of usage, even though the data in question were for his own private use and not shared with other users. In Microsoft’s terms of use8 there are prohibitions against material that “depicts nudity of any sort including full or partial human nudity or nudity in non-human forms such as cartoons, fantasy art or manga” or “incites, advocates, or expresses pornography, obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, hatred, bigotry, racism, or gratuitous violence.” With the emergence of such morality policing, items (images, sound files, videos) entirely legal to own, and unshared with other users, can put users in violation of the terms of service for a cloud provider such as Microsoft. What this also means is that cloud providers are (presumably periodically) scanning users’ files for potential violations of their terms of service. Big Brother is watching, even if you’re paying.

Some lesser-known cloud services—Wuala (wuala.com), SpiderOak (spideroak.com), and Tresorit (tresorit.com), for example—require users to encrypt all of their files before uploading any data to their storage services. Because the data encryption is performed on the user’s local devices (and only users know the encryption password) these providers couldn’t examine customers’ data even if they wanted to. Perhaps more important is that if “required” to make these files available to formal authorities or government agencies, they would be inaccessible. It is possible that the size/reputation vs. data sanctity trade-off will shift market sentiment toward smaller, less established providers that functionally eliminate the content vulnerability variable from the services purchase equation. Time will tell.

Taking an Active Role in Protecting Your Data

The industry is not ignoring the extent that operational considerations bearing on privacy coincide with market sentiment. In November 2013 the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) began surveying Internet companies about the privacy protections they offer to customers. The EFF has continued to update results from the survey as companies have adjusted upward the protections they offer (see Figure 6-4). The EFF is particularly concerned with operational protocols and mechanical features that protect consumers’ data in the event a government agency or other substantive body physically taps into the service’s fiber-optic (or other) data lines. The focus of the EFF survey isn’t mere paranoid hand-waving. The NSA was involved in just such line-tapping within the jurisdiction of its MUSCULAR program, affecting the data of millions of end users.

Figure 6-4. The results of the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s “Crypto Survey,” as of June 2014. (This figure is a derivative of “Encrypt the Web Report, Who’s Doing What”, by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, used under CC BY 3.0. https://www.eff.org/encrypt-the-web-report.)

The EFF survey asked data storage providers to respond to several questions regarding privacy. Does the provider flag all “authentication cookies,” small files used to store credentials, as secure, thus providing them only over an encrypted connection? Does the provider encrypt web sites with hypertext transfer protocol secure (HTTPS) by default? (HTTPS is the secure version of the web standard HTTP protocol.) Requiring HTTPS forces users’ connections to adopt an encrypted channel at all times. Does the provider incorporate HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS), a technology that forces a secure connection? When HTTP HSTS is used, it is more difficult for attackers to “spoof” a secure connection. In effect, the browser looks at the connection twice, in different ways, to ensure that it is encrypted. In the case of e-mail providers, is STARTTLS used? STARTTLS is a protocol that encrypts transmitted e-mails, but the transmission is secure only if both the systems from which the e-mail is sent and received use it. Does the provider use “forward secrecy” for its encryption keys? The forward secrecy protocol prevents a compromised key from being used to read past e-mail communications. Each key is good for only the current session, not past or future connections. As a body, this set of operational steps provides end users some level of e-mail privacy.

Critical also here is retention of users’ search privacy. In 2005, Apple was the first to introduce a “Private Browsing” mode, which it incorporated into the Safari browser. This operational mode, which is sometimes crudely referred to as “porn mode,” is designed specifically to not store any cookies, cached files, or other location identifiers on a computer’s hard drive. Google’s Chrome browser followed in 2008 with an “Incognito” mode, and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer (see Figure 6-5) and Mozilla Firefox added their own similar camouflage functionality in 2009. The most popular mobile device browsers also have added this functionality. In theory, when these filtering modes are used during an Internet search, Internet activities leave no traces on the local computer.

Figure 6-5. Microsoft calls the privacy mode in Internet Explorer InPrivate Browsing and presents this warning when it is activated. As of 2014, all major desktop and mobile browsers offer a similar feature

This works, in theory…. In practice, the various camouflage functions offered by Google, Microsoft, et. al are not 100 percent effective. These modes do effectively obscure searches stored on the local computer. However, a record of users’ Internet activities can still be found on a corporate firewall, the telecom company’s DNS (Domain Name Server [or System or Service]) equipment, or other network infrastructure. A more secure way to conceal Internet activities from prying eyes is through the use of a proxy browser.

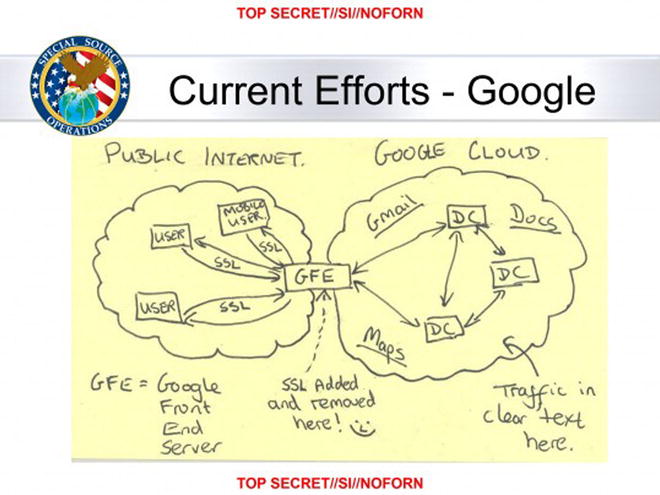

A proxy browser can be used for additional privacy protection. A proxy browser, as the name implies, serves as a “proxy” for end users, disguising their true identity and location. The most well-known proxy browser, Tor, is a free tool that can be found easily on the Internet. Tor completely separates end users from their activities on the Internet. This does not mean that activities and users become invisible online. Rather, while a “snooping” government agency or corporation can identify the user, and can also identify sites that have been visited, snoops cannot connect the two sides of the equation and link users with sites. Tor obscures any connection between specific sites and specific users.

Figure 6-6. When using an insecure browser and the HTTP protocol, a user’s complete set of activities, location, credentials, and other data are available to a hacker, a government agency monitoring the connection, the user’s ISP, and any groups these agencies collaborate with

Tor actually uses an onion as its logo to advance the analogy of inserting “layers” between what a user does and the identification of those activities. Users’ data and identity are protected as traffic is routed through several different Internet relays (see Figures 6-6 and 6-7). For example, when a non-proxy browser (such as Apple Safari or Google Chrome) is used to browse to a web site (such as cnn.com), that traffic passes from users’ devices, to their ISP or telecom provider (Verizon, AT&T, Comcast, etc.), to CNN’s servers, and back again. If no specific precautions are taken, users’ identity, their physical location, and their desired web site (along with any related credentials) are totally visible to the destination site, the telecom provider, and any eavesdropping organizations that happen to be paying attention.

Figure 6-7. When using the Tor browser and the HTTPS protocol, the user’s traffic is routed through a series of Tor “relays.” A hacker, a government agency, and the user’s ISP can see some of the user’s data, but not all of it together. The site being visited gets most of the user’s data, but not his or her specific location/identity, which is obscured by Tor. (Figures from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, used with permission under the terms of a Creative Commons license [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/].)

In contrast, when using a browser such as Tor, user traffic is bounced through several relays on the way both to and from the destination. Each Internet relay has access to only one layer. Tor is often used to circumvent filters that organizations impose to block social media, news sites, and other potential “time wasters” that can distract employees during work hours. Because Tor systematically obscures the source of online traffic through this relayed approach, content filters cannot identify prohibited web sites or other sources and correctly block them.

Somewhat ominously, it appears that the NSA is focusing more attention specifically on Tor users. Code for an NSA program called XKeyscore has been analyzed by researchers. The software seems to focus specific surveillance activity on users outside the United States who visit the Tor home page or even conduct Internet searches for private browsing options.9 Ironically, for users concerned about their online privacy the best defense may be a good offense. The larger the Tor user base grows, the harder it will be for governments to track individual Tor users, who increasingly become, in essence, a user block.

Private searching isn’t easily done without switching to a separate browser. However, another approach to conceal or protect Internet searches is to use a search engine called DuckDuckGo (DDG). DuckDuckGo does not store IP addresses or user information. In August 2010 DDG announced a collaboration with the Tor network allowing for completely anonymous end-to-end Internet searches. DuckDuckGo may be developing into a more serious competitor for established search engines like Google and Bing. Users can “switch” to DuckDuckGo simply by opening duckduckgo.com in their web browser, instead of google.com or bing.com. DDG is poised to get even easier to use in the near future. In June of 2014 Apple announced that DuckDuckGo will be an available search option in the Safari browser in the upcoming versions of both its desktop (OS X 10.10) and mobile (iOS 8) operating systems.

Data at Rest

Different possibilities emerge when the issue is the protection of users’ “local” data. This kind of in situ protection begins with whole disk encryption (WDE). Modern operating systems available through Apple and Microsoft include options offering users the capability to encrypt their entire hard drive. This means that, without a proper password or other authentication method, any data stored on the hard drive are inaccessible. For example, if a thief steals a laptop incorporating an encrypted hard drive, he or she can’t access the drive without knowing the encryption password. Even if the thief physically removes the hard drive from the laptop, the contents will be scrambled gibberish. Apple calls its WDE variant FileVault. Microsoft refers to its product as BitLocker. There also are third-party offerings on the market, which include commercial products like Symantec’s PGP Whole Disk Encryption and Sophos SafeGuard and the open source DiskCryptor.

Application of the WDE process provides users with reasonable assurance (against the casual or commercial snoop) that only authorized users can gain access to their computer. Most systems incorporate a PIN or password authentication gate. Other systems use a smart card or token in lieu of (or increasingly in conjunction with) a password in multilevel protection schemes. Without access to the proper logon credentials or materials, all of the data stored on the hard drive remain encrypted and unreadable. The end user of course may be forced or coerced into providing logon credentials, through threat of legal action or physical violence. The latter is referred to as “rubber-hose cryptanalysis”—mitigating the protection offered through WDE.

Previously, we hedged, noting that WDE offers reasonable assurance of protection against unauthorized computer access. In reality, it is possible that even the most sophisticated WDE may not protect against government surveillance. In September 2013, the New York Times reported that the NSA had circumvented or cracked most corporate and consumer encryption tools. Some of these private systems had been accessed through stealth approaches. In other cases, surprisingly, manufacturers had actually collaborated in this effort and inserted a “back door” at the government’s request, allowing unfettered systems access.10

In light of evidence pointing to the widespread erosion of protocols protecting individual privacy, until recently a popular alternative to corporate WDE products, and one believed to be independent of NSA surveillance, was a product called TrueCrypt. Released in 2004, TrueCrypt was an open source product, developed for noncommercial use and available for free download. In true techno-thriller fashion, the product was developed by an anonymous group known only as the “TrueCrypt Foundation.” The software was multiplatform, supporting Windows, Mac, and Linux PCs. Surprisingly, given its obscure parentage, many organizations recommended TrueCrypt as an officially sanctioned encryption product. Its multiplatform capability, corporate independence, ease of use, and the fact that it was free (!) likely off-set the mystery of its origins, making it enormously attractive.

In an effort to confirm the security offered by TrueCrypt, an audit of the software was successfully crowd-funded in October 2013. Continuing the techno-thriller theme, a group calling itself the “Open Crypto Audit Project” claimed to be in contact with the anonymous developers, who announced their support of the project. The first phase of the audit, completed in April 2014, reported finding no significant vulnerabilities in the software and no evidence of “back doors.” The second and final phase of the audit was scheduled for completion in October 2014. In the interim, on May 28, 2014, TrueCrypt’s developers announced that the project would be discontinued. A new version of the software was released that could decrypt files but that could not encrypt them. Speculation among security professionals focused on whether TrueCrypt had been forced to cease operations by a government agency, or whether the software had somehow been exploited or compromised. As of the writing of this book, no evidence of a security compromise had been unearthed. Further thickening the plot, there has been no recorded occurrence of TrueCrypt encryption having been “cracked,” or data being obtained from an encrypted machine without the password.

![]() Note As an extended aside, US courts have generally ruled that a private citizen cannot be forced to divulge an encryption password. This is considered “self-incrimination” and a violation of the protections offered by the Fifth Amendment.

Note As an extended aside, US courts have generally ruled that a private citizen cannot be forced to divulge an encryption password. This is considered “self-incrimination” and a violation of the protections offered by the Fifth Amendment.

Additional Reading

For more on protecting your data from eavesdroppers, see the following links, and visit our web site at www.10donts.com/snoops.

- Wired magazine’s “Threat Level” blog, which focuses on issues of online privacy, security, and crime: www.wired.com/category/threatlevel/

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s “EFF’s Encrypt the Web Report,” tracking the major Internet companies and their levels of data privacy: www.eff.org/encrypt-the-web-report

- Gizmodo, “Tor Is for Everyone: Why You Should Use Tor,” featuring an explanation of Tor’s features and a walkthrough on how to use it: http://gizmodo.com/tor-is-for-everyone-why-you-should-use-tor-1591191905

- Lifehacker, “How to Encrypt Your Email and Keep Your Conversations Private,” featuring a detailed guide on using PGP for e-mail encryption: http://lifehacker.com/how-to-encrypt-your-email-and-keep-your-conversations-p-1133495744

- Daily Mail, “The Edward Snowden Guide to Encryption,” with screenshots and the full video produced by Snowden: www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2628082/The-Edward-Snowden-guide-encryption-Fugitives-12-minute-homemade-video-ahead-leaks-explaining-avoid-NSA-tracking-emails.html

- PC World, “Three Practical Reasons to Use Your Browser’s Private Mode,” with explanations and instructions: www.pcworld.com/article/2106766/three-practical-reasons-to-use-your-browsers-private-mode.html

- PC World, “So Long, TrueCrypt: 5 Alternative Encryption Tools That Can Lock Down Your Data,” with reviews and links to built-in OS encryption methods and third-party options: www.pcworld.com/article/2304851/so-long-truecrypt-5-encryption-alternatives-that-can-lock-down-your-data.html

______________________________

1Wire, Philip Bump, “How Big Is the NSA Police State, Really?” www.thewire.com/national/2013/06/nsa-datacenters-size-analysis/66100/, June 11, 2013.

2Washington Post, Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani, “NSA Infiltrates Links to Yahoo, Google Data Centers Worldwide, Snowden Documents Say,” www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-infiltrates-links-to-yahoo-google-data-centers-worldwide-snowden-documents-say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-4166-11e3-8b74-d89d714ca4dd_story.html, October 30, 2013.

3New York Times, Vindu Goel, “Facebook to Let Users Alter Their Ad Profiles,” www.nytimes.com/2014/06/13/technology/facebook-to-let-users-alter-their-ad-profiles.html?_r=1, June 12, 2014.

4Wall Street Journal, Jack Marshall, “Do Consumers Really Want Targeted Ads?” http://blogs.wsj.com/cmo/2014/04/17/do-consumers-really-want-targeted-ads/, April 17, 2014.

5American Bar Association, Diane Vaksdal Smith and Jacob Burg, “What Are the Limits of Employee Privacy?” www.americanbar.org/publications/gp_solo/2012/november_december2012privacyandconfidentiality/what_are_limits_employee_privacy.html, November/December 2012.

6Wolters Kluwer Employment Law Daily, Ron Miller, “Employees Have No Reasonable Expectation to Privacy for Materials Viewed or Stored on Employer-Owned Computers or Servers,” www.employmentlawdaily.com/index.php/2011/11/24/employees-have-no-reasonable-expectation-to-privacy-for-materials-viewed-or-stored-on-employer-owned-computers-or-servers/, November 24, 2011.

7Wired, Andy Greenberg, “The Ultra-Simple App That Lets Anyone Encrypt Anything,” www.wired.com/2014/07/minilock-simple-encryption/, July 3, 2014.

8Windows, http://windows.microsoft.com/en-GB/windows-live/code-of-conduct, April 2009.

9Ars Technia, Cyrus Farivar, “Report: Rare Leaked NSA Source Code Reveals Tor Servers Targeted,” http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2014/07/report-rare-leaked-nsa-source-code-reveals-tor-servers-targeted/, July 3, 2014.

10New York Times, Nicole Perlroth, Jeff Larson, and Scott Shane, “N.S.A. Able to Foil Basic Safeguards of Privacy on Web,” www.nytimes.com/2013/09/06/us/nsa-foils-much-internet-encryption.html?ref=us, September 5, 2013.