Chapter 1. Partnership

“If we are together nothing is impossible. If we are divided all will fail.”

Winston Churchill

“In this new wave of technology, you can’t do it all yourself, you have to form alliances.”

Carlos Slim Helú

“If you can run the company a bit more collaboratively, you get a better result, because you have more bandwidth and checking and balancing going on.”

Larry Page

“Keep away from people who belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you too can become great.”

Mark Twain

Have you ever seen what appears to be a simple, straightforward technical decision unwind into political chaos? Conversely, have you ever seen what appears to be a politically charged decision just flow through without so much as a ripple of tension in the organization? In both cases, there seems to be a mystical force at work behind the scenes.

In the world of architecture, technical decisions need to be made every day. The needs of the business from both a short-term and a long-term perspective need to be considered. Your ability to determine the right direction and to convince those who need to implement it, to bear the operational costs, and to sell it will determine whether you are a success or a failure.

This chapter unveils one of the essential skills needed by a software architect: the ability to quickly form and establish partnerships.

What Is a Partnership?

A partnership is a relationship in which mutual trust is established. It is the willingness to stick together and pursue a goal even in the face of opposition. For an architect, forming partnerships is critical—it allows you to focus and present a common front when opposition comes.

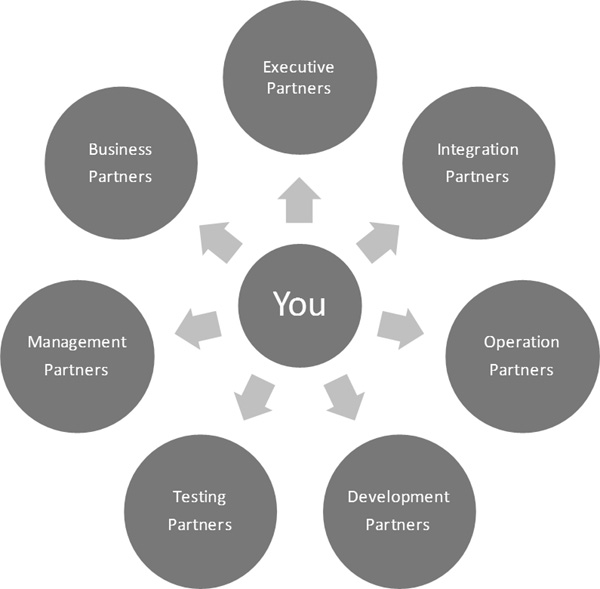

Architecture is a social activity. The more buy-in you have, the more likely you are to succeed. Understand who your partners are; they will act as your guideposts (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Partnership success formula

The ability to partner with others allows you to avoid being an island. In the world of technology, islands are easily defeated even when the goal or purpose is the right thing to do. On the other hand, a band of partners is not easily defeated.

What Are the Key Aspects of a Partnership?

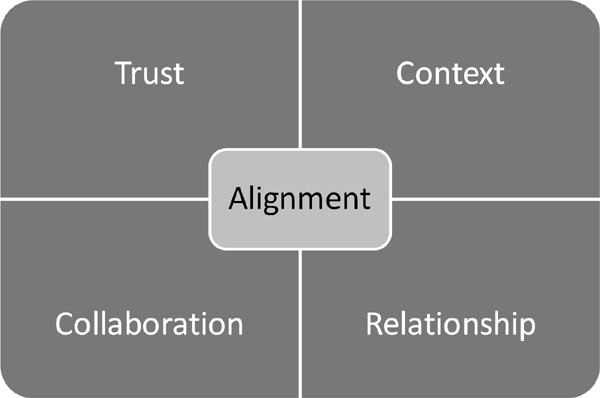

The key elements of a partnership are alignment, trust, context, collaboration, and relationship (see Figure 1.2). Understanding each aspect is the focus of this chapter.

Figure 1.2. The elements of partnership

Taking the time and effort to build partnerships within both the business and technical communities is a time-proven formula for success.

Alignment

Establishing a community for the purpose of guiding the architecture of the software and services related to a business is essential to ensure that the business’s near-term goals and the long-term vision are well aligned.

With Whom Do I Need to Be Partners?

The set of partnerships that you need to form is multidimensional (see Figure 1.3). You need to form partnerships with those above you (executives) within your business unit and potentially within other business units. You need to form partnerships with those who will be doing the work (managers, testers, coders, operations, etc.). You need to form partnerships with those who are your peers (other architects, directors). You may also need to form partnerships with those who are your integration partners (within your organization, across organizations, and potentially across companies). And finally, you need to form partnerships with the business (new product development, marketing, sales, finance, strategy, etc.)—those who fund technology efforts.

Figure 1.3. You and your partners form a circle of trust and transparency.

So, you might be saying to yourself, “It sounds like I need to be partners with everyone.” The short answer is: to the greatest degree possible and to the extent that time allows it, yes. The time spent to collaborate with more people in making a decision (or minimally creating awareness of a decision) will serve you well. Not everyone will care passionately about the decision, but all will appreciate being informed. As a practical matter, there is usually only a limited amount of time in which to make a decision, and you will need to decide who the critical stakeholders are before you execute. One really quick way to evaluate who these stakeholders are is to ask the following questions:

• Who will pay for the development costs? The licensing costs?

• Who will pay for the maintenance? The scaling costs? The safety costs?

• Who owns the assets being created?

• Who will pay for the migration costs?

• Who will pay for the reengineering costs? If the reengineering occurs within a year of the project’s initial development, this may be an issue. If it occurs more than three years out, it most likely is a nonissue.

• Who will pay for the operational and legal costs?

• Who will develop the product? Test it?

• Who owns the resources for development? For operations?

• Who owns the intellectual property rights?

• Who owns the policies governing development?

• Who owns the deployment? Who determines where the product will be deployed? Are there regional, national, or international laws governing the deployment?

• Who owns the long-term strategy? Are you enabling it or disabling it?

The short answer is to start by following the money. Who will be financially impacted by the decision? Who is seeking what is best for the customer? These are your future partners. Their role as business leaders, as well as yours, is to find ways to grow the business and ensure its future sustainability.

Finding the Thought Leaders

In every business, there are those individuals who have significant influence with respect to the technical directions that are considered acceptable and desired. They have the right contacts within the industry, they have a solid sense of what is happening throughout the industry, and they have a finger on the pulse of technology.

These are the individuals to whom you need to listen.

Even if it is from a distance, learning what they are interested in and watching the directions in which they are heading can give you a model to emulate. It can also give you a likely safe path for technology-related decisions in areas in which you are not an expert. If you follow their technology directions, you need to understand the rationale for them and ensure that they apply to your situation.

If these individuals work at your business, you may have the opportunity to meet with them occasionally and use them as a sounding board for any tougher situations that you encounter.

Knowing the Influencers

The influencers are the individuals who can accept, reject, override, or negatively influence the decisions being made. In the world of architecture, these are often other architects, directors, VPs, senior VPs, and CTOs.

These individuals may or may not be directly involved with your project, but they hold the attention of most individuals in management when it comes to making decisions in particular areas. If they are not on board with the decisions you make, they will either directly or indirectly exert their influence to negatively impact those decisions.

The key is to discover who the influencers are and what areas of expertise they have. When decisions about directions apply, you are usually best off seeking their opinion. This serves multiple purposes.

First, they usually are experts and have good insights into the pros and cons of heading in certain directions. It is unlikely that your situation is completely unique, and they may have encountered it before; they may have a good sense of what has or has not worked in the past. They may also have a sense of what direction the company or industry is heading in this area.

Second, as others within the organization come to them to get a sense of whether the decisions being made are reasonable, the experts have an opportunity to act as salespeople for you. They will understand your problem, the approach you are seeking to take, and the solutions that were or are under consideration.

They are now acting as partners instead of outside consultants.

Establishing Trusted Adviser(s)

As an architect, you need to establish a small advisory board of trusted individuals with whom you can share ideas and from whom you can get honest feedback. They can help identify gaps in the approach you are taking, risks that may be associated with the approach, other benefits of the approach that you may not have considered, or others you may want to consult.

Community Review (Architecture Review Board)

In some organizations, there is a process of community review of ideas, technical decisions, and approaches. This review is an opportunity to gather feedback about ideas at various stages. The process can be useful for a variety of reasons; most people will give you

• Honest feedback on their similar experiences from the past

• Suggestions for alternatives you may want to consider

• Ideas for others you may want to consult

• Agreement that the approach is reasonable (which can be useful later on, to show that the decision was not made in isolation)

The goal is to use the community to leverage other people’s experiences and knowledge.

Seeking Alignment before Making Key Decisions

Architecture review boards can often derail the architectural directions you are trying to promote. To help prevent this, take the time to meet with key architects in advance of the board meeting to ensure that their concerns are addressed. This will help enable the architectural review to run smoothly for a couple of reasons. First, either key stumbling blocks have been removed or a better rationale for the decisions will have been created. Second, the group will require less education and you will likely now have allies who can help sell your architectural approach.

Unity helps drive consensus.

When there is a lack of unity, these meetings can turn into a feeding frenzy, even when the underlying architectural approach may have been reasonable.

Remember, you get only one shot at a first impression for the project you bring forward, and it will be a reflection on you. What type of impression do you want to leave?

Alignment of a Shared Vision Enables Partnerships

My personal experience has been that once you have alignment in a shared vision with strategic and noble aspirations, establishing partnerships is a natural outcome. Several years ago when I was working with new product development, we were trying to solve a challenging customer problem about how to quickly and easily access relevant information. The conversation continued over a series of weeks.

Over this time, we looked at every imaginable solution both inside the company and outside the company. The more we dove into the problem, the more key elements of the customer needs began to fall out. Our vision of where we needed to take the product line began to emerge. The technology to pursue this vision simply did not exist, but we could start to see a roadmap of how we might achieve the vision over the course of several projects and several years.

Our shared vision aligned our projects, architecture, and funding for the next three years, created new capabilities across multiple products, and resulted in a patent being issued.

Trust

Partnerships are founded and flourish on the notion of mutual trust. Without it, they will slowly wither away.

Establishing Trust

When you are partnering with individuals, you need to develop a sense of trust. That is, you need to be very clear about the situations in which you are asking for help. If there are any risks, previous history about the situation, or stories behind the story, you should be open with this information.

Part of establishing trust is to disclose the good as well as the bad. Allowing the other person to make a decision about whether or not to support your idea is important. Eventually the facts will surface, and your disclosure, or lack of it, will become very obvious to those involved. Early disclosure is almost always the correct path to choose, even when it is to your disadvantage.

Listen to your partners’ responses closely; they may identify risks, other solutions, or even better sales material.

Establishing Open Disclosure

When dealing with your partners, you need to operate in a manner of open disclosure. You may not be able to fully disclose all the information you are aware of due to constraints of confidentiality or the timing of public disclosure, but you, to the degree possible, should communicate openly.

Note

When you disclose information to your partners that they shouldn’t have access to, you are letting them know that you do not honor the confidentiality of others and that you might distribute information that they provide to you in confidence to others. It is essential to maintain your integrity and act in a trustworthy manner.

As you are asking for guidance or approval, you need to be clear about the problem or solution that is being discussed. Giving the appropriate background information will ground your partners in what you are dealing with. This includes disclosing

• The context of the problem or solution (what project it is related to, who the customers are, what time frames you are dealing with, requirements, usage information, etc.)

• Previous history related to the problem or solution, especially within the organization for similar situations (are others using it and if so, why; if not, why not)

• Known risks associated with the problem or solution

• Previous attempts at solving this problem (successes and/or failures)

• Alternatives considered, including their pros and cons

• Cost-related information (development, operational, licensing)

• Scale or usability information

• Related licensing restrictions

• Pros and cons of what you are considering

The key here is to let the partners know that you have done your homework and due diligence in presenting the information. This will enable them to fully understand the lay of the land and to give you real feedback. Otherwise, you are just trying to get them to support a conclusion you have already made, and you are wasting their time and unnecessarily lowering their level of trust.

Avoiding Getting Spread Too Thin (Overcommitting)

The opportunities for distraction for an architect are extremely high. There are always new projects, new technologies, new areas that need help. The challenge is that there are only so many hours in a day. If you say yes to everything, you will need to work 25 hours a day. It’s not possible.

The other challenge is that you may be asked to do something for one of your partners—one who may have just saved your back, and you may not even be aware of it—and you may have no spare time. You may have to say no, and saying no doesn’t always come easily.

Note

If you commit, you need to follow through—no ifs, ands, or buts—no exceptions. Your word is your honor. If you commit and fail to follow through, you will at best lose trust; at worst you will lose your partner.

One of the best ways to combat this problem is to establish margin in your day, that is, purposely set aside time to act as a buffer. Guard this time closely; it will help keep you and your partners sane. Be cautious; the fact that you have a spare hour or two in your day doesn’t mean you should take on another commitment.

Sometimes there are seasonalities that come into play when you know you are going to be unusually busy or unusually free of commitments. When these occur, you will know in advance to either guard your time with extra caution or be more available to help others.

How to Unwind after You Have Overcommitted

If you are like me, once or twice a year all of your projects seem to have major time commitments converging at the same time. To deal with this, you can pursue several options.

The first option is to simply work more. The challenge with this is that the work of architects is highly social. A significant portion of their time is spent working with other people, and this tends to be during core working hours. There is only so much work that can be shifted away from the core work hours.

A second option is to evaluate the work you are doing and determine if any of it can be delegated to others. On most projects, there are some tasks I like to reserve for myself, such as investigating new technologies. Usually when I start feeling overwhelmed by the amount of work I am doing, it is because I have chosen to take on too many tasks that I deem fun. In reality, I need to start delegating and allow others to do the fun work. It’s a hard thing to do, but it gives others an opportunity to grow and learn.

A more drastic approach is to stop taking on new projects or assignments. Sometimes passing on that new and exciting project is the right thing to do; the project won’t seem so exciting when you are swamped and are unable or barely able to keep pace with all of your commitments. In reality, this is effective only with the help of your manager. There are a very limited number of times you can do this, so proceed with this option cautiously.

If you are unable to avoid taking on new work, the best route is to simply let each of the projects know that you are being stretched thin and that you will be spending less time with them. Ask them to engage you specifically when they need your help. Clear communication about the situation will resonate with others and enable them to understand how to determine the times and situations when it is appropriate to engage you.

As an architect, you need to know your limitations. Often the reward for good work is more work. When this happens, it is up to you to recognize the situation, manage your time efficiently, avoid overcommitting, and definitely avoid underdelivering.

Learning to Say No

Managing your time so you don’t get overwhelmed usually involves saying no. Learning to say no is essential to establishing trust.

When you are an architect, questions, requests, and consulting sessions can simply consume all of your time. The challenge is to figure out which ones you absolutely need to address yourself. In almost all circumstances, you need to listen for a while to figure out what the issue at hand is. If you don’t have time to deal with it immediately, you may need to ask your colleagues to come back later or, if possible, redirect them to someone else on the team who can help them.

Once you have had a chance to listen to and hear what is being requested, you have to make a determination of whether you have time to deal with the request.

Realize that you are the easy answer if you take on the request. Others may simply be trying to optimize their time instead of investigating the issue on their own. Sometimes letting others struggle a bit is not a bad thing. It will enable them to learn how to research an issue and to work it through the organization. Sometimes people are looking to get out of trouble; they may be handing you a bad situation that they created because they don’t want to deal with it themselves.

Most people have legitimate requests, but if you are swamped, you need to figure out if someone else on the project can take on a new request. On the other hand, if it turns out to be a critical issue that is likely to get raised up to senior management, you will want to drop everything you are doing and deal with it immediately.

Issues that involve senior management need to be managed very carefully. You do not want to let such issues be learning opportunities for the person making the request. Whenever senior management gets involved, the set of possible outcomes can vary dramatically. Now isn’t the time to say no.

Before you say yes, understand the commitment (Is this really your problem?), the amount of time needed, and the amount of risk you are taking on if you say yes or no.

Often just giving people additional ideas about how they can move forward can get them off and running again. Are there others to whom they should talk, websites that have the information they need? Can they dig into the problem a little more deeply and then come back if they still haven’t solved the problem?

Realize that the people you are dealing with are your partners. You are either adding value or removing value from the relationship, so be conscientious about how and when you say yes or no.

Remember, you may need their help in the future.

Trust Enables Transparency—the Lifeblood of Partnerships

Your ability to quickly and easily access information within your organization is critical to your success.

Recently, I had a chance to be included in an interview meeting with a customer about a new product area. The detailed information about the work the customer does illuminated the product ideas in a stunning fashion.

I am always amazed at how little I know about these new areas when this process starts and how much there is to know about the context of a customer for a new product area. I know that I need to immerse myself in the problem domain before I really begin to understand how to approach a reasonable solution to the customer’s needs. It is always exciting to start a new journey into unknown territory.

I know trust has been established with my business partners when they are willing to include me in customer visits for their new areas of business innovation. This transparency about their business goals and direction enables me to make solid architectural decisions literally for years to come.

The customer visits usually give me more context about the business problem we are trying to solve than nearly any other experience I am likely to have. The experiences and the product conceptualization conversations that follow get indelibly etched into my mind and make for great projects.

The key is to remember that this journey doesn’t start early unless trust has been established and maintained with business partners. They are not required to engage technologists when they interact with customers; it’s a privilege to be included, not a right.

Context

Partnerships rely on operating in a particular context. This context helps frame the alignment, trust, collaboration, and relationship of the partnership.

Realizing the Nature of the Partnership

In life, context is critical to getting things right. Partnerships are no exception. Understanding the nature of the relationship with respect to your relative status within the organization is essential.

A person who is higher than you within the organization is likely hoping that you can provide a good sense of the current state of technology, what trends are occurring, and the success or lack of success a particular project is having.

A person who is more of a peer is likely looking to you as a sounding board for ideas, for help in an area where you have expertise, or for ideas on how to approach certain problems.

A person who is lower than you in the organization is likely looking for guidance on how to solve a problem, information about what opportunities may exist within the organization, or approval of a certain approach.

No matter whom you are interacting with, take the time to understand the context of the situation. This can help you determine how best to serve the person who is requesting your help.

Being Aware of Your Business Context

Architects need to be aware of their business context when advising partners on direction. The business context for an architect includes what markets the company is trying to enter or maintain and any specific policies that are enforced with respect to security, open source, procurement, and related areas.

The business context can help you quickly determine whether a particular project is viable.

Embedded within the business context is an increasing need for architects to understand the cultural and national differences of the various groups with whom they interact. This is driven in part by the nature of many projects today that can span geographic regions, and in part because individual teams that are involved in the projects include a wider diversity of people with different cultural and national backgrounds.

Technical Decisions Require Partnerships

Technical decisions narrow the set of future options available to the business. If you choose to make a hack for the solution, you are committing the business to future investment in that area if it needs to make a more strategic play. However, your hack may also enable the business to get to market more quickly and allow a refactor once the product has gained market acceptance. Having others on board (partners) with the technical decisions you make is essential to your future career health.

If the right parties were not involved with an earlier decision, they will have no impetus to defend what was done even if it was the right thing to do. The current thinking style and current development rules will be applied with no regard to the past. If you were the lone wolf on this decision, you are about to get sacrificed.

Take the time to gain key approvals anytime you are “hacking” the system or leveraging a legacy system that is scheduled for decommission. It is almost always an easy answer if you are doing a strategic solution and the business is willing to take on the cost.

The main point for seeking technical partnerships is to ensure that you are capable of delivering the well-understood results for the price specified. Coming back later to ask for more money is rarely well received.

Key Point: Technical Decisions Are Political Decisions

You might ask, “Why in the world is a technical decision a political decision, especially when I hate politics?” The answer is relatively straightforward: the decisions you make today will either limit or enable future options. You are in some very real sense putting handcuffs on the business. When the bill comes due, the business executives are likely to remember who made the decision. Of course, everyone wants to have all future options available, wants to be part of the decision making, wants to have the project cost a small amount, and wants to have it scale easily and inexpensively.

The larger the impact of the technical decision you are making (whether it be financial or strategic), the more carefully you will want to vet the solution, to ensure that you have the proper buy-in, and to know the scope of your decision. You will also want the business to understand the cost of making the decision as this will help drive the architecture and the decision process.

Presenting the Situation First (Give Context)

When presenting information, there is a tendency to want to dive into the problem, to quickly justify why your solution is correct, and to receive the praise of others on the brilliant solution you have devised.

The challenge is that most people do not have your context and need more background information to get to a point where they can reasonably evaluate what you are presenting.

One effective way to approach this is to use a process of presenting information called SCRAP (situation, complication, resolution, action, politeness) (see Figure 1.4). This is also occasionally referred to as SCQA (situation, complication, question, answer).

Figure 1.4. Context-driven selling: one of the easiest ways to get everyone on the same page when presenting a solution to a problem is to use SCRAP.

The idea is to

1. Start with the situation (nondisputable facts that everyone can agree upon)

2. Introduce the complication (the problem that needs to be solved)

3. Show possible solutions to the problem

4. Call the audience to action (how they can help)

5. End politely (thank everyone for their help and input)

This simple mechanism can be used to guide your partners to a solution without jarring them with low-level details and having the conversation be derailed. This technique is especially effective with executives. They need a clear, concise context for a situation before jumping in to help resolve it.

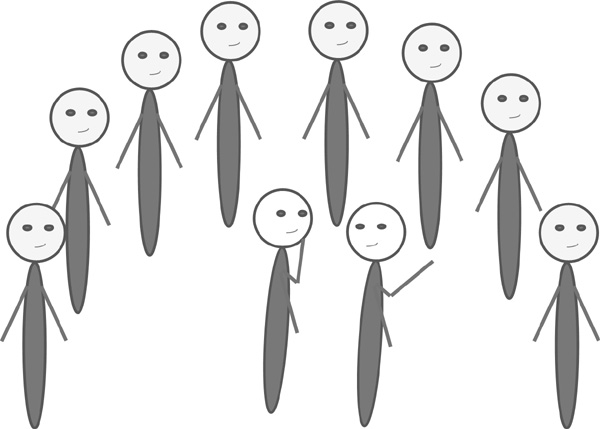

Having Your Partners’ Back

When you have taken the time to cultivate partnerships throughout the business, you need to guard those relationships carefully. Many conversations occur during the day. During these conversations, if someone is saying negative things about one of your partners, if possible you need to defend the person or correct the statements that are being made. Having your partners’ back and standing up for them is part of being a partner (see Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. When your partners are being surrounded and attacked from many fronts, step in and help defend them. You will earn their trust.

If you don’t defend them, silence is normally considered agreement. Worse yet, if you add fuel to the fire by disclosing information that puts them in a bad light, you are throwing them under the bus and thereby destroying a valuable relationship or minimally lowering its value. When this information gets back to the party involved (it usually does), it will take a significant amount of time and effort to undo the damage that was done.

Sometimes this is referred to as “keeping it in the family.” Every family is dysfunctional at some level, and work is no exception. Present a united front and work out the differences offline.

Contributing to Your Partners’ Success

Find ways to help make your partners successful. When there is an opportunity to put in a good word for them, to help them out in areas that are not directly related to the projects you are currently working on, or to provide feedback on their other projects as a trusted adviser, take the time to invest in your partners’ success. Small things can go a long way toward helping bolster your partners’ success.

Safety in Numbers

Whenever you are in architecture, you are in sales. You are typically selling a technology, a solution, an architecture, or some other key area. The broader the support you are able to build, the easier it will be to gain acceptance of the idea you are bringing forward.

Often within an organization, selling a solution isn’t just about numbers; it is about having the right support. Knowing who the influencers are in your organization and gaining their support can make acceptance of an idea or direction much simpler.

Collaboration

In a business context, a partnership’s success relies on the ability of those involved to work together toward common goals by contributing their best ideas in a cooperative environment. The spirit of collaboration can enable an open environment for conversations to occur and ideas to be reshaped and reformed. This reification of ideas is where innovation can spring to life.

Bringing Value to the Table

Most partnerships need to be more than a one-way street to information and guidance. You need to provide value in return for the information and guidance you receive. Often this means giving open feedback about information others may be seeking, ideas they may want to consider for projects they are working on, alternative approaches to solving problems they face. As you find information, websites, blogs, articles, or conferences they may be interested in, taking the time to forward this information to them can help balance the value of the partnership.

Becoming a Mentor

As an architect, you often encounter many opportunities to mentor others. During the course of any given year, I typically work on mentoring a handful of individuals. Usually, they are individuals who are looking to get promoted at some point in the future.

The key to developing a successful mentorship relationship is to understand what the individuals are hoping to learn:

• Do they want to learn a specific skill?

• Do they want to learn what the role of an architect is?

• Do they simply want to do their current job better?

Once you understand the direction in which they want to go, you can work on finding reading materials, blogs, or potentially even project-related tasks that they can help you with. Often doing is the best way to learn.

Try to find a regular time when you can meet, whether once a week or once a month. Having a set regular time will help guarantee that you do in fact meet. Most mentoring relationships usually last about a year.

Sometimes formal mentoring programs are offered through a company or through local organizations. Sometimes the mentoring organizations are primarily for the purpose of bringing mentors and mentees together. Mentorship can take place as paired individuals or sometimes as a group activity.

Before you begin meeting, you should plan what you want to accomplish and tentatively put a plan together for how you are going to get there. The amount of preparation your mentees are willing to do in advance will be an indicator of how serious they are about working to improve themselves.

If you set an agenda in advance of each meeting and have whatever preparatory materials distributed and reviewed in advance, it will make the time you spend together much more productive.

At some point, giving feedback is essential. Mentees need to understand if they are on the right track or if there are other areas they may want to consider improving. One of the best pieces of feedback you can give is the strengths that you see; knowing that they are particularly good at something can help give them the confidence they need to pursue their goals. The areas where they need improvement may be very difficult to change, and many times the best they can do is minimize the impact of these areas.

Overall, seek to give mentees honest feedback and encourage them.

Seeking a Mentor

Over the years, I have had a series of mentors. I am always amazed at what they can see about me. They are able to quickly pick up on areas that I need to work on—areas that I thought I was actually good at—and, on the other hand, see strengths that I have that were not immediately obvious to me.

When seeking a mentor, you want someone who will give you a straight answer and tell you the things you need to hear, even when you don’t want to hear them or may not agree with them. Often, these are things that are apparent to others, but not obvious to you.

I have had mentors both inside and outside of my organization. In general, the mentors inside the organization are better because they are aware of the organizational culture and politics. They have a much better sense of how to navigate the organization successfully.

You need to have a sense of what you want to get out of a mentoring relationship. You need to be clear with the mentor about what your goals are, what you are seeking to become, what you have tried to date, and what you are planning on doing in the future. Giving your mentor a sense of the books you like to read, the blogs you follow, and any training you may have sought or are seeking will help inform the mentor about where you are within your career.

Have a plan for how often to meet and the goals of each meeting. This is your time. You should drive the agenda, but listen for feedback and adjust based on that feedback.

The results of mentoring are usually not immediately obvious, but over the course of three to five years, you can see the changes that have occurred, and you may discover that some of the piercing words about things that you needed to work on were in fact true. Once you have a little more perspective, it is usually easier to see that these statements were accurate.

Partnerships Can Be a Source of Opportunity

Usually as new opportunities present themselves within the business, there is a certain lead time and limited revelation of the scope of the opportunity. Your network of partners will determine whether or not you are considered for the opportunity or even have a chance to hear about it.

When you do have a chance to hear about such opportunities, be willing to jump in and take a risk. If your partners are asking you to consider the opportunity, you usually already have their backing and support.

Normally, these types of opportunities do not present themselves on a regular basis. If you say no now, you may put yourself out of consideration the next time; so think quickly and be willing to jump even if you don’t have all of the details.

Partnerships Are a Step toward Ideation

For architects, gaining the trust of the business and forming partnerships are essential. These partnerships eventually lead to the business being willing to draw you into the inner circle. It is inside this inner circle that the directions for the business are set. It is the place that will determine the future work and opportunities you will have. It is the home of ideation and discovery.

Collaboration Drives Stronger Partnerships

In today’s world of fast-moving technology, collaboration is essential to provide competitive solutions. It is rare today that you have the ability to be the expert in all of the areas related to a solution for a customer. This collaboration needs to occur on multiple levels.

You need to collaborate with your customers to continually navigate toward high value. This may involve giving them early access to your pipeline of solutions to get critical feedback. You need to collaborate with your supply chain of technology providers to find solutions that will last and scale; this may take the form of proofs of concept, access to industry-leading experts for advising on technology selection, and specialized training.

My experience has been that the companies that are in the forefront of new technology areas, where the open-source community is beginning to thrive, have unique industry insights and are able to give expert guidance on the use of these new technologies.

These forms of collaboration both within the company and outside of the company will help solidify your community of partnerships and can provide significant value for all parties involved.

Relationships

Partnerships are established and maintained through relationships. These relationships both inside and outside an organization are essential for architects to be successful.

Partnerships Are Not Just about Business

As you develop partnerships, you need to develop and maintain the relationships. Although partnerships are critical to succeed in business, you need to cultivate them. Taking the time to get to know the people better—learning what they like to do for hobbies, who their kids are, what their kids like to do—will go a long ways toward establishing a better partnership.

Find time to go out for lunch, get coffee, or just stop by to chat. You will find your days are more enjoyable. As with all things, be aware of what the cultural norms are to ensure that you are engaging with others in an appropriate manner.

Making Deposits before You Start Withdrawing

As with most relationships, there is a give-and-take to helping each other out. When one party makes continuous withdrawals, the interest level in maintaining the relationship becomes strained. Make sure you take the time to keep in touch and help out whenever possible; this will make it easier for you to ask for help in the future.

External Partnerships

Staying in contact with those who have changed business units or have left the company can be an excellent way to develop partners. In addition, being active in local user groups or conferences can also be an excellent way of keeping a broad network of people who can help advise on particular issues.

Knowing what other businesses are using for tools or what processes they are following can help inform you about what changes are occurring in the industry. They can also give you a sense of what types of projects local executives are approving.

A strong internal and external professional network is critical to maintaining success and also serves as a source of technical and business expertise that a single person would have difficulty developing and maintaining alone.

Bad Experiences in the Past?

Get over it. Suck it up. You need to make sure the right people are involved with decisions. If you don’t, it will come back to haunt you.

For good or bad, whether you get along with someone or not, sometimes you need to get over your previous bad experiences with the person and draw him or her into a conversation. Learn to be polite, and ignore the past.

When you enter these situations, know what you want when you go in. Getting information that will help the business succeed is the right thing to do even if it’s painful.

When you are finished, say thank you. The person may not even remember the previous event that is so fresh in your memory.

Avoiding Caustic Members of the Organization

There are always certain individuals in every organization who love to demean, destroy, and belittle others. They effectively establish fear in others and use that fear to their advantage. They are often caustic individuals and are generally politically aligned well enough that they are safe from being removed from the organization.

Although they may carry influence within the organization, it is usually best to avoid them. There is almost no good that can come out of interacting with them, and there is usually a large downside to interacting with them unless you enjoy a good fight.

If you do need to interact with them, it is usually best to let them speak their piece without interruption. Keep track of any points you wish to make, but make sure everything you say is well reasoned. The key is not to interrupt. Usually, this is not a conversation; it is more of a monologue.

Summary

The road to partnerships begins with

• Establishing alignment

• Finding the right partners

• Finding the thought leaders

• Knowing the influencers

• Establishing trusted advisers

• Leveraging community review

• Aligning a shared vision

• Establishing trust

• Establishing open disclosure

• Avoiding overcommitment

• Learning to occasionally say no

• Establishing context

• Understanding the nature of the partnership

• Being knowledgeable of the business context

• Framing technical decisions with a partnership

• Realizing that technical decisions are political decisions

• Learning to sell with a context

• Having your partners’ back

• Realizing there is safety in numbers

• Establishing collaboration

• Bringing value to the table

• Being willing to be a mentor and knowing when to seek a mentor

• Recognizing opportunities

• Enabling ideation

• Establishing relationships

• Being more than just about business

• Making deposits before you begin withdrawing

• Leveraging external relationships

• Overcoming bad experiences from the past

• Avoiding caustic members of the organization

For architects, establishing partnerships across multiple areas of the business is essential for survival. Architects live in a highly politicized world and are constantly being challenged for the decisions that they make.

You need senior executives, business partners, and others to understand and support the decisions that have been made. They can defend you when you aren’t present. Without these partners, you will get the opportunity to view the underside of the organization as it drives over you.

References

Bradberry, Travis, and Jean Greaves. 2009. Emotional Intelligence 2.0. TalentSmart.

Bruch, Heike, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 2002. “Beware the Busy Manager.” Harvard Business Review, February.

Covey, Steven M. R., with Rebecca R. Merrill. 2008. The SPEED of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything. Thomas Nelson.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2002. The Tipping Point. Back Bay Books.

Maxwell, John C. 2001. The 17 Indisputable Laws of Teamwork: Embrace Them and Empower Your Team. Thomas Nelson.

Patterson, Kerry, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler. 2011. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second Edition. McGraw-Hill.

Schwartz, Tony, and Catherine McCarthy. 2007. “Manage Your Energy, Not Your Time.” Harvard Business Review, October.