Corporations implement scorecards to monitor and drive performance for sustaining profitable growth. Operations lead to financial outcomes, and stronger financial performance supports operations. Therefore, the success of the Service Scorecard depends on how it is being used by executives for reviewing operational and financial performance. To ensure the active participation of executives and middle management, the Service Scorecard has leadership and acceleration elements.

The leadership element is critical to set the bar, demand performance, and align the organization to achieve business objectives. The Service Scorecard can be implemented successfully by utilizing the following areas:

Technology for ease of data gathering and reporting

People for their participation in developing goals and taking actions

Process level measurements to provide feedback in real time

Leadership at the process level

A culture of excellence to strive for the best

Teamwork to ensure broader implementation and positive interaction

In most organizations, the performance measurement task is assigned to the IT department or the assurance organization to ensure its implementation. Such implementations lack teeth to get anything done except reporting numbers. For example, there was a reporting manager who used to publish monthly performance reports religiously within the first week. At one point the manager took a vacation, left a stack of reports close to the door of his office, and notified all interested parties to pick up their copy. On his return from vacation, he was surprised to find the stack of reports without one copy missing. He then stopped publishing the report, and no one bothered to ask about it. Such an example is not an uncommon attitude about the scorecard.

With the technology available today, scorecards are displayed as dashboards, so people look at the dashboards. They are accustomed to seeing green, yellow, and red zones on dashboards. When it comes to implementation based on the yellow or red zones, excuses such as “it’s old data,” “the problem no longer exists,” or “it’s the other departments’ fault” are not uncommon. The leadership element is designed to eliminate such excuses, reward superior performance, and establish unquestionable accountability for performance.

Most businesses strive for continual improvement. One of the challenges with continual improvement is that managers are used to setting up realistic and marginal goals for improvement. They spend time reporting the achievement of those goals without being sensitive to the impact of improvement on corporate financials. At many companies, managers report improvement month after month, but employees do not see any improvement. They see reports of improved profit, but they also hear about upcoming layoffs. When such ironic incidents occur, questions inevitably arise. Either the improvement is not enough to overcome the financial challenges, or the growth is not enough to benefit from the improvement effort.

Today every company has some form of improvement initiative, be it lean manufacturing, Six Sigma, TQM, or another similar initiative. When a customer looks to establish a relationship with a supplier, it reviews competing bids for price, the quality management system (QMS), and service. At the time of evaluation, discriminating among potential suppliers is very difficult, because they all have QMS certifications, competitive prices, and customer service departments. All suppliers are incrementally improving in a roughly equal manner; thus, it becomes difficult to discern a good supplier from a bad supplier. The rate of improvement in a supplier’s performance, as measured by the Service Scorecard, can provide great insights about its internal operations, culture, leadership, and likelihood of being a dependable supplier.

Acceleration is required to achieve excellence, synergize departments, and demand passionate leadership commitment to achieve business objectives. Typical continual incremental improvement initiatives lead to employee boredom, management apathy, and leadership ignorance. Such incremental improvement initiatives become a champion’s job, and the champions look for justification for one’s existence through myriad improvement projects, unnecessary training, and a confounding and fancy reporting system.

Leadership and Acceleration in the GLACIER of the Service Scorecard form critical arch stones. Leadership inspires employees to excel, and Acceleration drives improvement. Most business successes are headed by inspiring leadership, such as Steve Jobs at Apple, Bill Gates at Microsoft, Jeff Emmelt at General Electric, Bob Galvin at Motorola, Herb Kelleher at Southwest Airlines, Louis Gerstner at IBM, Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway, Michael Eisner at Disney, and Lee Iacocca at Chrysler. On the other hand, many business failures, such as Enron Corporation, Tyco International, DeLorean Motor Company, TWA, and Arthur Andersen, can also be attributed to leadership failures. The corporate leadership makes or breaks the company at any state.

Simple analysis will show that if one strategy will ensure corporate success, it is acceleration in improvement. If every department, including design and development, continually improves significantly, then the corporation will do well. The strength of a company is determined by how fast and how much an organization can adapt to changing conditions. Continual improvement must be a habit. In some critical areas, inefficiency must be remedied and waste must be eliminated fast, as the profit margins become limited and prone to rapid deterioration due to intense global competition. Acceleration in performance improvement must become a major corporate initiative, mandating clearer accountability, faster improvement, and dramatic results. Acceleration facilitates growing profits.

Service organizations are becoming more complex, more autonomous, and more interdependent in the changing Internet economy. Service organizations such as telephone service providers, banks, restaurants, airlines, education institutions, regulatory and compliance organizations, IT service providers, and R&D service providers have both global reach and local impact. In order to lead an organization with attributes such as local and global presence, in-house and outsourced services, human- and technology-based services, personal and infrastructure level options, and centralized and distributed systems, leadership must be able to do the following:

Handle complexity while keeping it simple.

Learn technology while inspiring people.

Empower people while ensuring performance of the organization.

Due to this significant and critical latitude in the performance of an organization, the Service Scorecard includes the leadership element with guiding measurements such as employee recognition and profitability. Continually inspiring employees by having them actively participate in strategic as well as operations planning is now a more important aspect of leading an organization. For example, Colleen Barrett, president of Southwest Airlines, has said the following about the significance of stakeholders: employees first, customers second, and shareholders third. In service organizations, employees and their happiness matter, because the happier the employees, the more pleasantly they will serve customers. The leader of a service organization must be other-oriented instead of self-oriented to ingrain a service attitude in the organization.

The Leadership element is supported by the other elements of the scorecard to create synergy and achieve synchronization among various departments. The leadership role is critical in achieving sustained profitable growth. A decision by leadership may lead to action by all employees, resulting in a significant impact on the performance. Thus, the leadership decisions are weighted at 30 percent of the total forming the Service Performance Index (SPIn). Assigned weights are baseline weights and will vary depending on the business context.

One of the challenges in today’s corporations is that the CEO is involved more in dealing with external aspects of the business, such as shareholders’ concerns, Wall Street expectations, major individual investors, key customers’ concerns, or external communication through various media channels. As a result, leaders know more about what is not going right and what they should say, rather than what they should do more or better. The Leadership element of the Service Scorecard ensures a certain level of engagement and ensures that critical activities are performed.

Typical leadership expectations are to establish a vision for the organization, ensure strategic planning and execution to realize desired business objectives, communicate to inform various stakeholders, ensure a sound financial bottom line and top line, monitor compliance to government regulation, and be available at critical opportunities to meet with employees, clients, or other stakeholders. Successful CEOs or leaders are fast learners, whether that learning is about new technology, new product designs, or new methodologies similar to Six Sigma, Lean Manufacturing, or Innovation. Every CEO or president is a very smart person. Questionable strategy and tunnel vision are what misdirect corporate resources and lead to unsatisfactory business performance.

Vast literature resources exist on the leadership topic. Some popular themes of leadership are the stewardship approach requiring a servant-leader paradigm, the empowerment paradigm providing enablers to get things done, and the learning organization approach. Leadership has been defined as a process, as a relationship providing influence and motivation of personality traits, as a system of processes, and as an instrument to achieve desired corporate goals. Most of these approaches, however, fail to take the situation or business context at hand into account. Some of these approaches are also idealistic in nature. Additionally, none of these approaches appears to have been tested empirically. The situational (that is, contingent) approach of leadership is the most relevant for the Service Scorecard.

The transformational approach of leadership considers the business context and includes transactions and relationship elements. Considering leadership styles as a continuum, the transformational style is on the far-left corner, the transactional style is in the middle, and the hands-off approach is on the far-right corner. The Service Scorecard measures the impact of leadership on employees and other stakeholders. In this section, the transformational approach to leadership, as described by Peter Northouse in his book Leadership: Theory and Practice, is examined. The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire is based on the elements of transformational leadership. The questionnaire is divided into three broad leadership styles:

Transformational style—. Leadership showing transformational styles, including influencing, visioning, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration.

Transactional style—. Leadership providing rewards and placing checks and balances/corrections in place. Rewards and recognition are measured in the Service Scorecard.

Hands-off leadership—. Leadership places no rigid structure or guidance or rules in place.

Current trends in globalization, service mix, technology advancements, the use of intellectual resources, and tough competition require continually rapid organizational changes that add other dimensions to the leadership job. Globalization demands working with multiple organizations, dealing with people with diverse backgrounds, and communicating with businesses having a variety of cultures, government policies, and laws. All of these factors add to the complexity of the organization and challenge the leader to look for optimal and multidimensional solutions. So many tasks and the complexity of working with such organizations require that the CEO stay focused on his task of bringing out the best in people everywhere.

While developing measurements, the challenge for the leadership is that there can be so many important measures that could be established. However, too many measurements for CEOs could lead to “runaway” CEOs, because they do have to deal with subtle aspects of the business. Selecting the two best measurements for the leadership must define roles clearly for the CEO. One measure is to inspire employees to do their best for producing outstanding results that create significant value for the organization through the CEO Award recognition. Employees or teams love to be recognized with the CEO Award for Exceptional Value. A trivial-looking aspect of the CEO Award is its publicity. The CEO Award must be publicized to create interest in employees to strive so that they identify areas for creating exceptional value.

Every employee wants to do a good job at work with the given tools, information, and knowledge (provided motivation exists). Bureaucracy and recognition for “waste savers” prevent employee engagements, especially in large organizations. Thus, CEO recognition of the employee provides the extra incentive for employees to strive for innovative, extraordinary performance. In smaller companies, employees are closer to the CEO or the president; however, in most larger organizations with a deep hierarchical layer, employees can not even think of seeing their CEO in person. An opportunity to be recognized by the CEO provides huge motivation to create significant value.

The second leadership measure for the Service Scorecard represents the CEO’s commitment to create value for stakeholders. Thus, Return on Equity (ROE) has been identified to be the second measure for leadership. This requires CEOs to continually monitor the financial performance of the corporation to satisfy the fundamentals of the business for ensuring ROE. For some businesses ROE may not appear to be a suitable measurement; however, the organization may decide to replace ROE with a similar measurement. Each measurement has been weighted at 15 percent for its contribution to the Service Performance Index (SPIn). For the leadership element and measurements to work effectively, the CEO must own these measures of performance personally and participate actively to achieve business objectives.

Having a CEO responsible for financial performance is the ultimate measure of the leadership performance. There is a long list of financial measures that corporations utilize. Selecting one that is representative of the CEO’s performance makes a difficult choice. ROE or an equivalent measure is a tangible and critical measure of the leadership’s performance. Most corporations have a ROE measure in place already; however, they do not necessarily utilize it to monitor corporate performance.

Leadership buy-in for implementing the necessary measurements is an imperative. No leader wants to be measured with the understanding that a leader is accountable for the overall performance of the company. By depending on the overall performance, the CEO is taking a chance of achieving desired business objectives without personally getting engaged. He must be willing to be held accountable for the necessary actions and expected outcomes. Many measurements can be used; however, selecting the two measurements, wherein the one is the input to the business performance and the other is the output of the business performance (ROE), makes sense for the Service Scorecard.

Initially, the CEO recognizing extraordinary performance may sound trivial. The intent is not to give awards; instead it is to inspire employees to give their best to the CEO’s vision and to the company. Accordingly, appropriate resources must be allocated, and organizational responsibilities must be assigned. For the CEO recognition to work as intended, clearly defined criteria for recognition must be established and communicated to all employees. The recognition must be inclusive and fair to all employees; otherwise, it would create more discontent rather than fulfilling its intent to promote intellectual engagement of all employees.

Most important of all is the CEO’s personal effort to achieve established goals for the two leadership measurements. Responsibility of the leadership measurements should not be delegated; instead the CEO must demonstrate personal passion and set an example of going after performance measurements. The CEO’s staff responsible for other performance measurements would certainly follow the CEO’s lead in planning, executing, and achieving the desired business objectives.

Planning for the leadership measurements can include input from stakeholders such as managers, employees, and customers, and a team must be formed to establish guidelines to gather information about exceptional successes, evaluate various successes, select successes for recognition, communicate those successes to the organization, and recognize individuals involved in creating the exceptional value. Besides, aggressive goals must be set to install the culture of continually raising the bar higher, whether annually, quarterly, or monthly.

One of the major challenges to establishing meaningful leadership performance measurements is creating a culture of accountability all the way from the top to the floor. If goals are established they are meant to be achieved; if reviews are held they are meant to challenge the status quo; if actions are identified they are meant to be completed on time to deliver desired outcomes. If one department needs help from others, priorities must be aligned and help offered. Such is the culture in which everyone is working toward achieving business objectives, making decisions in the interest of the organization, and optimizing department processes with team spirit, thus minimizing interdepartmental conflicts.

A CEO is respected as a leader if a clear vision is communicated, employees are inspired, and the organization is creating value for customers, employees, and society. The previously stated two measures provide leading indications of the CEO’s success.

If a company has only one measurement as a leading indicator of the corporate performance, that measurement is acceleration. Acceleration is defined as the rate of improvement. Corporations have been improving their performance for many years. Large OEMs demand price reduction from their suppliers at a rate of about 2 percent to 5 percent every year. Wal-Mart asks its suppliers to improve performance and reduce cost on an ongoing basis. To meet customer demands, suppliers must find a way to cut cost. Initiatives using Six Sigma or Lean Manufacturing are implemented to reduce scrap, eliminate waste, or streamline processes. However, competitive forces require that this rate of improvement be accelerated. Indeed, the Six Sigma methodology works optimally when improvement targets are aggressive, thus forcing involvement of all employees and executives.

The Acceleration element in the Service Scorecard has been incorporated to create a culture of relentless and dramatic improvement for keeping up with competition and changing customer demands. Acceleration overcomes built-in organizational procrastination by forcing the middle management to take responsibility for rapid and dramatic improvement. Imagine the ability of a person to walk, jog, run, and race. Walking involves mostly the legs; jogging utilizes the stomach for retrieving energy; running involves the heart; and racing gets the head actively engaged. In a similar way, the hearts of people do not get involved unless we accelerate people to get involved to promote and realize improved performance.

For an organization to accelerate improvement, all employees must be synergized. In other words, when employees get intellectually involved, creativity sprouts, new ideas are born, and innovation occurs. Thus, it is critical for an organization to accelerate improvement to sustain profitable growth for overcoming the rate of inflation, increasing customer demands, higher employee compensation, and inefficiency in the newer processes.

The Acceleration element affects all other elements of the Service Scorecard as well as all aspects of an organization. Acceleration implies that each department head must establish aggressive goals for improvement, develop an action plan to achieve goals, monitor progress, and take necessary action to ensure progress as intended. One of the barriers to accelerating performance is the fear of failure that occurs due to setting arbitrarily aggressive goals, committing insufficient resources, and missing the established improvement target. Leadership in the organization must allow risk-taking, understand failures, and encourage aggressive goals. In the absence of such an environment, managers tend to set goals that are achievable and nonchallenging. As a result, organizations perform below their capability and miss the opportunity to improve corporate performance.

To establish aggressive goals, benchmarking must be performed to assess the market position and understand best-in-class performance levels. Considering the market position, internal inefficiencies, and waste of resources, managers can establish goals such that employees will be challenged to think creatively and do something different to reduce waste, gain competitive advantage, and improve corporate performance.

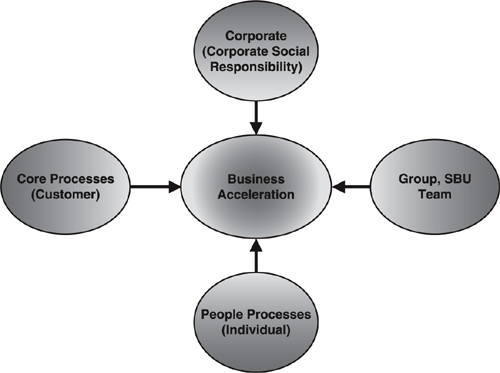

The Acceleration element illuminates the long-term commitment to continuous improvement. Business acceleration can be divided into the following categories, as shown in Figure 7.1:

Acceleration at the individual employee level—. Examples are employee performance and learning curves.

Acceleration at the team level or service group level or business unit level—. Examples are team performance indicators and service-time-to-market measures.

Acceleration at the process level—. Examples are process time and quality. These processes relate to core customer requirements.

Acceleration at the organization level—. Examples include improvement in corporate measures.

In his book Accelerate: 20 Practical Lessons to Boost Business Momentum, Dan Coughlin identified the importance of business acceleration based on his learning from various Fortune 500 and top private companies, including AT&T, Citigroup, Marriott, McDonald’s, and Toyota. No rigorous test is provided of this concept, however.

A common input of measuring acceleration in a company is the process of goal setting. Goal setting helps organizations focus on the results and outcomes and holds the party accountable for its actions. Clear expectations are set during the goal-setting process. The goals may be at the organizational level, process level, or business unit level. These goals may be objective or subjective, helping maintain or improve the performance, and at the process level or corporate level.

Benefits of accelerating improvement are multifold. Due to the aggressive improvement goals, teamwork is required. It creates interdependence among departments and sensitizes them to each other’s goals. Each department understands that acceleration in improvement is a corporate goal for everyone, so cooperation is critical and benefits are mutual. Acceleration promotes involvement of the customer for ensuring growth and exceptional service. Most important, once committed to accelerate improvement at an aggressive rate, the leadership and managers must both get passionately involved; otherwise, failure is imminent. Without the leadership involvement, a corporation cannot accelerate improvement.

Innovation is an outgrowth of acceleration in business performance. Normally, improvement and innovation are considered to contradict each other. Incremental improvement is all about consistency, whereas innovation is about disruption. When the improvement becomes dramatic, it requires innovation, as the new process must become consistent at the different level. Improvement can reduce inconsistency, whereas innovation can raise the bar. The typical goal for improvement must exceed the comfort level, forcing the new solution to be significantly different from others.

Being a nonconventional measure, practicing acceleration in improvement becomes the most challenging measure. The typical measure is the rate of improvement that is needed for each department. Besides being a new measure, another challenge is that this rate of improvement measure causes discomfort for managers, because it requires them to set an aggressive rate of improvement. Based on the market position, and internal opportunities for improvement, a typical rate for improvement may range from 30 percent to 70 percent in manufacturing processes and 15 percent to 30 percent in nonmanufacturing processes.

The improvement measures reduction in waste of both time and material. For example, if a typical process is yielding 80 percent, the rate of improvement goal could be set between 30 percent and 70 percent of the 20 percent waste. Similarly, if a sales process is producing a certain level of sales or margins toward the established profitable targets, the improvement goal could be a 15 percent to 30 percent reduction in gap from the targets. Of course, internal and external, as well as controllable and uncontrollable, constraints must be considered for each process. The controllable constraints could be fixed, while the uncontrollable constraints are managed with some uncertainty using statistical analysis.

To implement the rate of improvement measure, each manager establishes a baseline for the key processes and submits a plan to achieve dramatic improvement that mandates redesigning the process for superior performance. If a process is running close to perfection, or a process has a significant performance loss, the latter gets the priority in setting the departmental goals. In addition, if a process is very critical to the success of the department, that process gets the priority in setting departmental goals. However, goals must be set such that they make each department operate better, faster, and more cost effectively. After the department identifies key processes and its baseline performance, each manager submits the improvement goal and a plan to improve the performance.

The improvement plan includes key tasks, departmental responsibility, critical assistance required from other departments, and estimated date of completion. The improvement plan must also include methods of reporting and communicating the departmental performance internally and externally to the department. The report may include posting trend charts on a bulletin board, for example.

Experience shows that many performance reports show the final goal and performance with respect to the final goal. In such cases the performance target will be missed during most of the year. Even if incremental improvement is realized in some months, it looks like failure and can discourage employees due to lack of recognition. Therefore, dividing the year-end goal into monthly goals, and tracking the process performance against these monthly goals to ensure continual progress, is recommended.

The plan for accelerating improvement must be developed with extensive cross-functional participation. Breakthrough thinking is incorporated at the planning stage by setting aggressive goals and assigning tasks requiring innovative approaches. Otherwise, low-hanging opportunities will show an initial improvement that will hit an impasse in the latter months. Changing course in later months becomes difficult due to initial successes. Thus, the department manager must commit to an innovative approach at the planning stages.

Implementing acceleration requires passion and enthusiasm from the department manager, a culture of employee participation at all levels, and deployment of all resources. It requires leadership, the use of technology, the intellectual engagement of employees, knowledge management, benchmarking, research, and idea management. The department manager plays a significant role by demanding the improvement, providing resources and guidance, and monitoring performance. If the monthly goals are not achieved, all brains must be brought into a huddle to determine remedial actions with a sense of urgency. There must be awareness that the department expects excellent—not acceptable—performance. The standards of excellence are being on target. Highlighting performance targets regularly sensitizes employees to their responsibilities and consequences.

Both the Leadership and Acceleration aspects of GLACIER in the Service Scorecard are critical to continuous and improving business performance.

Leadership drives the performance and is the central piece of the Service Scorecard.

Creating a culture of accountability is very important to institute measures for the leadership element.

Acceleration drives rate of improvement and is driven by middle managers.

Acceleration and leadership elements both require cross-functional participation and buy-in.