Chapter 2

A New Business Frontier

Social and technology changes require a new way of doing business.

The rules of the road in business have changed. Just ask Uber.

In a few short years, the ride-sharing service both transformed the transportation industry and found itself crashing against new standards related to leadership, transparency, and fairness.

With its phone-based app for arranging car trips, Uber pioneered a new, cheaper, more convenient way of getting around. It jump-started the “gig economy” by tapping independent contractors rather than traditional employees and quickly became a global force. Eight years into its existence, Uber’s revenue in 2016 had raced to $6.5 billion and it was valued at $70 billion—$15 billion more than General Motors.16

But its brash CEO Travis Kalanick also steered into one accident after another. In January 2017, Kalanick and the company were slammed for allegedly seeking to profit when taxi drivers protested the Trump administration’s refugee ban. Fueled by a #DeleteUber campaign on Twitter, roughly 500,000 users reportedly asked to delete their Uber accounts in the wake of that incident.17

The negative publicity continued in February 2017. Former Uber engineer Susan Fowler published a blog post claiming a culture of sexism at the company—including her charge that Uber refused to punish her manager after he made sexual advances, in part because he was a “high performer.”18 There were legal troubles as well, including a U.S. Justice Department probe.19 Kalanick’s reputation was further bruised by a video of him losing his temper with an Uber driver over fare policy.20 Several executives departed amid all the troubles.21

Along with the scandals came a financial warning sign: Uber was burning through cash at an astounding rate. It posted net losses that rose to nearly $1 billion in the last quarter of 2016—an amount that may have been the largest quarterly deficit in business history.22 Meanwhile, rival Lyft added more than 50 cities to its operations, and other companies were considering entering the ride-share market.23

Uber tried to course correct in early 2017. The company put a plan in place to fix its culture, and fired 20 employees in June because of harassment, discrimination, and inappropriate behavior.24 And Kalanick pledged to get leadership coaching in the wake of his altercation with the driver.25 But it wasn’t enough to prevent investors from pushing him out of the driver’s seat.26 Kalanick stepped down as CEO on June 21, remaining on the company’s board of directors.27

What a Difference 20 Years Make

Whether Uber’s culture flaws, scandals, and executive shake-up amounted to minor potholes or an insurmountable roadblock remained to be seen as of mid-2017. But the company’s valuation undoubtedly backtracked amid all the trouble. And the very fact that it careened so wildly speaks to the way the business world has changed in the past two decades.

Think back 20 years, and one can imagine Uber zooming smoothly past most or all of its recent troubles. Back then, consumers were less concerned with the ethics and politics of the companies in their lives. There were no social media networks where a company protest could catch fire so quickly. The Internet wasn’t yet a platform for giving any unhappy employee a forum to publish their views to the world. Nor had a culture of self-expression emerged—one that is intertwined with the millennial generation’s demand for a meaningful, positive purpose and a growing willingness on the part of people to leave a job if the company doesn’t match their values.

Put simply, dramatic societal and technological changes are creating new challenges for organizations as they seek to attract the best talent as well as win over customers. The days of unreformed “bad-boy” CEOs are numbered. Rapidly changing competitive landscapes are putting a premium on agility and redefining what it looks like. The need for decentralized decision making increases the importance of getting the best from everyone. Also making people issues more crucial is a shift to an economy where essential human qualities such as passion, collaboration, and creativity are vital to business success.

In effect, we have entered a new business frontier. This chapter maps how the landscape has shifted thanks to social and technology changes. It explains why business must change to succeed, and shows that what was good enough to be “great” 10 or 20 years ago is not good enough now.

Social Changes

Businesses today are operating in a society that expects more out of companies, that is more demographically diverse, and whose members aren’t afraid of speaking up and out. In effect, people are holding the companies in their lives to a higher standard as consumers, investors, and employees.

In the wake of the Great Recession of 2008, consumers now seek “value and values,” according to research by journalist Michael D’Antonio and John Gerzema, the president of Brand Asset Consulting for global advertising firm Young & Rubicam. D’Antonio and Gerzema found that more than 71 percent of Americans are part of a “spend shift,” in which consumers are actively aligning their spending with their values. This shift cuts across demographic groups and is rewarding companies that demonstrate transparency, authenticity, and kindness in their operations.28

Meanwhile, American businesses face an increasingly diverse marketplace. Whites made up 80 to 90 percent of the U.S. population from 1790 to 1980. The year 2011 marked the first “majority-minority” birth cohort, in which the majority of U.S. babies were nonwhite minorities.29

The demographic changes come with cultural divides. Many baby boomers (those born from 1946 to 1964) and seniors (those born earlier still) resist the changing racial makeup of the country, while the millennial generation (those born from 1981 to 2004) is more inclusive. One study found just 36 percent of baby boomers thought more people of different races marrying each other was a change for the better, compared to 60 percent of millennials who applauded the trend.30

The millennial generation is one businesses have to pay close attention to, as both consumers and workers. Millennials surpassed their Generation X elders (born from 1965 to 2000) as the largest cohort in the U.S. workforce in 2015.31 That year, there were an estimated 53.5 million millennials at work, or about one-third of U.S. workers.

As employees, millennials prioritize meaning, balance, and job stability. A recent survey of 81,100 U.S. undergraduates found young people ranked an inspiring purpose as the most desired characteristic in an employer, with other top priorities being job security, work–life balance, and working for a firm with fewer than 1,000 employees.32 Millennials also expect a more personalized, development-oriented, participatory, collaborative, and transparent workplace, other research shows.33

That’s not to say that desires like purpose and cooperation are absent in people of other generations. After all, the “Greatest Generation” of Americans had the courage to defeat the Nazis in World War II, rebuild Europe, and put a man on the moon. Baby boomers and Generation Xers have had the vision and persistence to launch companies that have reshaped the way we live: firms like Microsoft, Genentech, Whole Foods Market, Apple, and Google, to name a few.

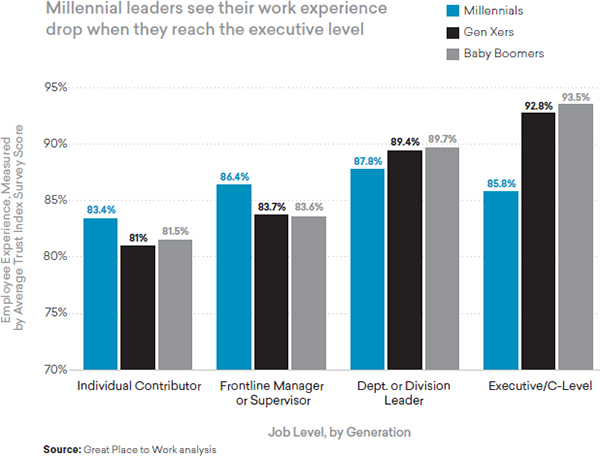

It could be that millennials have such lofty standards for work in part because they happen to have been raised during the economic boom of the 1990s. And many have entered the workforce during the U.S. recovery that began in 2009. In any event, this generation does stand out from others when it comes to the traditional climb up the corporate ladder. Our research, for example, discovered that baby boomers or Gen Xers generally have a more positive workplace experience the higher the job level they attain. Millennial executives, though, have a less positive experience than millennials in more junior management roles (see Figure 7). This could be a result of a clash between the demands of C-suite positions and millennials’ yearning for a rich life outside of work.

Figure 7

Millennials: A Dip at the Top

Millennial leaders see their work experience drop when they reach the executive level

What’s more, millennials are not afraid to seek employment elsewhere if their expectations are not met. Our research on different generations in the workforce found fewer than 5 percent of millennials who do not experience a great workplace plan a long-term future at their companies. That compares to 7 percent of Gen Xers and 11 percent of baby boomers who intend to stay at their companies despite not considering it a great workplace.

On the other hand, our data dispelled a commonly held myth: that millennials are inveterate job hoppers. We discovered that when young people are at a great workplace, they are nearly as likely as their peers in older generations to want to remain at their companies. Fully 90 percent of millennials who feel they are at a great workplace want to stay there for a long time. In other words, a great workplace makes a 20× improvement when it comes to retention (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Trust Drives Millennial Retention

Millennials also tend to voice their opinions and concerns publicly, in company forums, on Facebook, and in blogs. Former Uber employee Susan Fowler, who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a bachelor’s degree in 2014, is a case in point. Not only did Fowler quit Uber for another firm after just over a year, but she documented her experience for the world to see. Her account not only painted the company as negligent and deceptive regarding her sexual harassment claim but described a back-stabbing, chaotic culture in which a manager allegedly bragged about withholding “business-critical” information from one executive in order to curry favor with another.34

Fowler’s blog, in effect, was the last straw for Kalanick’s reign at Uber. She painted the company as the last place millennials seeking an inspiring, cooperative, transparent culture would want to join or do business with. And given the increasingly important role millennials are playing in the workforce and as consumers, no company can afford to leave this generation behind.

Technology Changes

Susan Fowler’s willingness and ability to blog about her Uber experience is directly linked to her coming of age in a world with technologies for widely shared self-expression. Internet blog platforms, social media sites, and related transparency tools are among the technology changes raising the bar for businesses. Other technological developments now facing companies include:

![]() Increased automation, which paradoxically is putting a premium on the deeply human characteristics of employees

Increased automation, which paradoxically is putting a premium on the deeply human characteristics of employees

![]() Big data and the need for analytical chops and a learning mindset

Big data and the need for analytical chops and a learning mindset

![]() Heightened digital connectivity, which is accelerating the pace of change and pressuring companies to decentralize decisions

Heightened digital connectivity, which is accelerating the pace of change and pressuring companies to decentralize decisions

Transparency Tools

Susan Fowler is far from alone in sharing her thoughts online. Overall, 69 percent of the public uses some type of social media platform, such as Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. That’s up from about 50 percent in 2011 and just 5 percent in 2005.35 Combine that mass usage with people’s inclination to discuss work along with the rest of their lives online, as well as the ubiquity of cameras, and nearly everything that takes place in or at a company is at risk of being exposed.

Consider what happened when a passenger was dragged off a United Airlines flight by police officers in early 2017 when he refused to give up his seat. A number of passengers recorded the incident on their phones and posted video on social media. The video quickly went viral and was picked up by major news organizations. In an earlier era, before smartphones and social media, the incident might have been a small news item if it was noticed at all. Instead, the episode turned into a public relations nightmare for United. The day after the incident, United’s stock fell about 2.8 percent, wiping out about $600 million in market capitalization.36

Increased Automation, More Humanity

Apart from the rise of technologies that effectively disrobe companies, the ongoing march of computing and automation are pressuring organizations to up their game in different ways. Much of the debate in recent years about the “rise of the robots” has been about the way they are reducing the number of jobs in America.37 That’s an important discussion for society overall. But a more immediate impact of automation on companies is counterintuitive: pressure to bring out the least-robotic qualities of the workforce.

In effect, our economy has evolved through agrarian, industrial, and knowledge phases to the point where the essential qualities of human beings are the most critical. Author Dov Seidman uses the term “human economy” to capture this transition.38 He notes that analytic skills and knowledge—chief traits of what have been called “knowledge workers”—are not advantages in an era of increasingly intelligent machines. Yet people, he writes,

will still bring to their work essential traits that can’t be and won’t be programmed into software, like creativity, passion, character, and collaborative spirit—their humanity, in other words. The ability to leverage these strengths will be the source of one organization’s superiority over another.

You can see this humanization of work in the shift away from customer service scripts in recent years. Leading hospitality companies, such as Hyatt, have abandoned the robotic responses to customer interactions that had been intended to optimize service levels. Instead, employees from front-desk agents to food service workers are encouraged to have authentic encounters with guests. A few years ago at our annual conference, Hyatt’s executive vice president Robert W. K. Webb told a striking story along these lines.39 A room service worker took a meal to a couple staying at a San Francisco Hyatt and struck up a conversation with them. He learned that they were staying in their room because the wife, in remission from cancer, was too tired to go out on the town that evening. The Hyatt worker, named Andy, also learned that he and the wife shared a love of music, and he began singing Frank Sinatra songs. The couple appreciated his crooning so much that they called for encores, hugged him as he departed, and invited him back the next night. He obliged—this time with Tony Bennett numbers.

The husband wrote Hyatt a letter in gratitude for these surprising serenades. Webb quoted the letter at our event: “The last thing that we were looking for was an experience with room service when we went to San Francisco. But it turned out to be the highlight.” The key to this lasting impression was that Hyatt has freed its employees to respond to guests with empathy, creativity, and passion. “Andy was himself,” Webb said. “It was magical for them in the moment.”

This shift in emphasis from “hired hands” to “hired heads” to “hired hearts,” as Seidman puts it, has important consequences for the way businesses manage people. The deadening, disheartening workplaces that most people experience will face an ever-larger penalty. The companies that thrive in the human economy will be the ones that make people feel alive, where workers feel they can bring their full selves, where people reach their full potential as human beings.

Big Data

So technology is pushing companies to make more-humane workplaces. But that’s not to say tech shrewdness is not important. On the contrary, firms have to be smart about using computing power to gain insights about all aspects of their business. “Big data” will only become a bigger deal in making savvy decisions about products, pricing, marketing, and people management. For example, assessing data about how employees experience the workplace under different leaders is crucial to making adjustments and optimizing performance. In general, the need to make data-driven decisions means business leaders will need a willingness to learn—that is, a measure of vulnerability, an open mind willing to forego intuition when the numbers show otherwise.

Digitization

A final technology change forcing companies to do business differently is ever-increasing digital connectivity. Even as growth in global trade has flattened, cross-border data flows have grown by a factor of 45 over the past decade, according to McKinsey Global Institute researchers.40 Those data exchanges are projected to increase another ninefold by 2020. These digital connections contribute to a faster pace of business, where innovations happen rapidly.41

Hyperconnectivity also leads to greater uncertainty. “The competitive landscape is growing more unpredictable as digital platforms such as Amazon, Alibaba, and eBay are empowering companies of any size, from anywhere on Earth, to roll out products quickly and deliver them to new markets,” the McKinsey researchers wrote in a 2016 Harvard Business Review article.42

A New Kind of Agility

A faster pace of business is pushing organizations to be more agile. But the combination of technology and social changes described above is redefining what effective agility looks like. Decades ago, senior executives could survey the business landscape, issue a command about how the organization would change direction, and expect to control the execution of that command.

That old-school command-and-control model breaks down, though, when the time it takes to collect information for a central decision maker can mean missed opportunities. As noted in the introduction, John Chambers, executive chairman of computer networking giant Cisco, deems the traditional, top-down mode of leading obsolete. “Creating an entrepreneurial culture that empowers every employee—from interns to engineers—to create the next big thing is essential to survival,” Chambers told us.

Like the shift to “hired hearts,” the move to decentralized decision making and what some call a “sense and response” form of leading also makes people management more important. More employees become pivotal to the company’s success. If they aren’t bringing their best, the company pays a steeper price.

What’s more, agility takes a new shape when employees are less willing to be treated as passive cogs in a machine. As discussed above, people today want a sense of purpose at work and to be included in the conversation about where the company is heading. And as changes come faster, the entire organization—everyone in the workforce—needs to be resilient and adaptable in the face of rapid shifts in strategy.

A new model of agility is emerging. Leaders’ traditional inclination to hunker down and coil in before springing is less effective. Instead, leaders increasingly must reach out and gather up everyone to manage change.

A good example of this involve-everyone agility can be seen at AT&T. Consider the way the communications giant has pivoted quickly in recent years. For one thing, the company has made radical changes in how it runs its massive network—handling capacity and services through software rather than hardware. In 2015, AT&T became one of the world’s largest providers of pay TV, with the acquisition of DIRECTV. Then in 2016, AT&T and its CEO Randall Stephenson took another bold step to become a major content player with a bid to buy TimeWarner.

As a result of such moves, what was once strictly a telecom company is now a major player in technology, media, and telecommunications. And this puts entirely new demands on its more than 260,000 employees, many of whom started in the landline phone business.

For obvious reasons, the nature of work is changing at AT&T. Soon, some 100,000 positions will require much different technical skills. Stephenson sees this as “the biggest logistical challenge we’ve ever tackled.” But AT&T isn’t going to solve the problem by simply letting go of employees who lack cutting-edge capabilities. And it isn’t focusing its investments just on “high-potentials.”

Instead, Stephenson and AT&T are working to bring all their people forward into the future. The company is inviting them to equip themselves for a digital future, at the company’s expense but on their own time. Partnering with educators and investing heavily in new curricula, AT&T aims to keep investing in workforce upskilling for the foreseeable future.

This isn’t purely a be-nice-to-workers move on Stephenson’s part. As he mentioned at our 2017 Great Place to Work For All conference, retraining existing AT&T employees for the jobs of the future makes the most business sense. “You could not just go out and replace 100,000 people,” he said. “Even if you were a heartless S.O.B., you could not make it happen. The reality was, we were going to have to come at this from the bottom up—build a plan for how you reskill and retool 100,000 people.”

AT&T’s strategy speaks to a new way of thinking about change and agility. It’s about developing and tapping everyone’s full human potential. Not only during static times—which are increasingly rare—but during times of tremendous change as well.

New Gig, Old Gig

We’ve discussed social and technological changes that have dramatically altered the business landscape and transformed organizational agility itself. There’s another shift that bears mentioning, an oft-cited change in the business world that isn’t as radical as it is sometimes portrayed: the gig economy. The rise of contract work arrangements, in which companies move away from traditional employer–employee relations, does change the workplace landscape significantly. It offers organizations greater financial flexibility even as it raises important societal questions about workers’ financial stability and well-being.

But what’s sometimes overlooked in conversations about the move to more contract work is that the key, fundamental relationship between organizations and workers doesn’t change. People are people. Contractors are drawn to companies they trust, just as employees are. Organizations still need to show contractors credibility, respect, and fairness to attract the best talent and get the most out of their gig workers. You might say that companies should give contractors an “arms-length embrace” to succeed with this growing practice.43 If they don’t show a measure of love to contractors, don’t treat them as partners more than transactional entities, organizations will stumble.

Uber, the poster child for the gig economy, learned this lesson the hard way in 2017. Consider the incident in which Travis Kalanick was recorded arguing with an Uber driver. The driver, Fawzi Kamel, told Kalanick that a fare decrease for Uber’s high-end “black” cars was unwise and hurt him financially. He says he lost $97,000 and went bankrupt because of Uber’s move. “People are not trusting you anymore,” he said.

Kalanick didn’t try to rebuild Kamel’s trust in the exchange. Instead, he offered this retort: “Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own s***. They blame everything in their life on somebody else.”

In this case, though, Kamel forced Kalanick to take responsibility for his own “s***.” Kamel sent a copy of his dashboard video recording to news outlet Bloomberg. That move turned what would have been a minor annoyance to Kalanick 20 years ago into yet another public relations headache. The incident prompted Kalanick to send a remorseful email to Uber’s entire staff. “To say that I am ashamed is an extreme understatement,” Kalanick wrote.44

Several months later, Kalanick was out as CEO, and the company was working to restore trust with its people and with the public. Whether Uber would succeed remained to be seen. But the company’s series of high-profile accidents showed that the economic landscape has transformed over the past two decades. Fundamental changes in society and continued technological advances have created a new set of challenges and opportunities, and a new way of managing change itself.

What was good enough to be great is different today.

It’s a new business frontier.