Core Values Management at the World’s Oldest Universities

Case Study 1: Jagiellonian University

Name: Jagiellonian University in Kraków.1

Country: Poland (Krakow).

Date of foundation: Founded in 1364 (as the second university in Central Europe) by King Casimir III the Great, who received permission from the Pope to establish a university in Krakow, the capital of the Kingdom of Poland.

Motto: PLUS RATIO QUAM VIS (“let reason prevail over force”).

Form: A public university.

Rector/President: Professor Karol Musioł, PhD (from September 1, 2012, Prof Wojciech Nowak, PhD).

Structure: Jagiellonian University is composed of 17 faculties (which have different organizational sub-structures): Law and Administration, Medicine, Pharmacy and Medical Analysis, Health Care, Philosophy, History, Philology, Polish Language and Literature, Physics, Astronomy and Applied Computer Science, Mathematics and Computer Science, Chemistry, Biology and Earth Sciences, Management and Social Communication, International and Political Studies, Biochemistry, and Biophysics and Biotechnology.

University colors: Blue and yellow.

Enrollment: Total 51,601 students, including 2,941 PhD students and 2,648 postdiploma students.

Employees/Administrates: Total 7,083, including 6,499 faculty and 584 staff.

Alumni: no data.

Notable alumni: Marcin Bylica of Olkusz (chief astrologer to King Matthias Corvinus in Buda), Marcin Biem (astrologer who devised a reform of the Julian calendar), Jan of Glogow (the author of numerous mathematical and astronomical tracts, known all over Europe), Nicolaus Copernicus (astronomer), Jan Virdung of Hassfurt (a professor at Heidelberg University), Johann Vollmar (a professor at Wittenberg), Konrad Celtis (astronomer), Saint John Cantius (philosopher, physicist, theologian), Erasmus Horitz (astronomer), Stefan Roslein (astronomer), Maciej Miechowita (professor of medicine, prominent physician, historian, author), Adam of Bochen (professor of medicine), Jan Dlugosz (historian), Jan Kochanowski (author), Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski (author), Marcin Kromer (author), Mikolaj Rej (author), John III Sobieski (King of Poland), Karol Olszewski (chemist), Zygmunt Wroblewski (physicist, who were the first to liquefy oxygen and nitrogen from the air in 1883, and later also other gases), Napoleon Cybulski (physiologist, who explained the functioning of adrenaline), Tadeusz Browicz (anatomopathologist, who identified the typhoid microbe), Marian Smoluchowski (physicist, the author of major works on the kinetic theory of matter); Leon Marchlewski (chemist, who conducted research on chlorophyll), Paulin Kazimierz Zurawski and Stanislaw Zaremba (whose outstanding research gave origin to a new school of mathematics), Edmund Krzymuski (professor of penal law), Fryderyk Zoll Jr (professor of civil law), Stanislaw Wroblewski (professor of Roman and civil law), Wojciech Boguslawski (actor, theater director, founder of the national opera), Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II).

Brief History

In 1364, after many years of endeavor, King Casimir the Great received permission from the Pope to establish a university in Krakow, the capital of the Kingdom of Poland. It was the second university to be founded in Central Europe, after Prague in 1348. Soon afterwards, other universities were established in the area: in Vienna (1365), Pécs (1367), Erfurt (1379), and Heidelberg (1386). However, the Studium Generale in Krakow, as the school was then called, started functioning practically only in 1367. It consisted of three faculties: liberal arts, medicine, and law. King Casimir’s premature death in 1370 and the total lack of interest in the University demonstrated by his successor, King Louis of Anjou (King of Poland and Hungary), led to its gradual collapse.

The University (or the Academy, as it was called then) was restored, due to the endeavors of Queen Jadwiga, who pleaded its case with the Pope in Avignon and later bequeathed her personal effects to the University, which was re-established in 1400, after its benefactress’s death. Henceforth it was a full medieval university, consisting of four faculties (including theology). As it followed the pattern of the University of Paris, its Rector was elected by the professors. Colleges with accommodation for the professors and dormitories for students were founded. The restored Krakow University soon established itself in the world of learning.

In the seventh century, the Academy—involved in a violent conflict with the Jesuits who, supported by King Sigismund III, attempted to control it—increasingly conservative and scholastic, lost international academic status. It shared the nation’s declining position on the European stage. However, in spite of adversity, the Academy managed to establish a wide network of associated schools, known as “Academic Colonies.” The first of them was its own secondary school, Nowodworski College, founded after the reform of the teaching system in 1586. But the Academy also experienced the siege of Krakow by the Swedes in 1655 and was plundered after the surrender of the city.

In the eighteenth century, the University continued to decline, yet some signs of change became gradually apparent. The systematic teaching of German and French was introduced, as well as lectures in Polish law, geography, and military engineering. Fundamental reform at the University, such as new organizational structure, was introduced and a number of academic facilities were founded, such as the astronomical observatory, the botanical gardens, clinics, and laboratories. All lectures were in Polish, and scholars educated at foreign universities in the spirit of the Enlightenment were appointed professors, to disseminate Enlightenment ideas among students.

The third and final Partition of Poland posed a serious threat to the very existence of the University, but fortunately it was saved by the intervention of Professors Jan Sniadecki and Jozef Bogucki in Vienna. However, the University was subjected to the process of obliterating its Polish character and to its gradual reduction to the secondary school status. This threat disappeared after Austria’s defeat in the war with France in 1809, when Krakow was incorporated into the Duchy of Warsaw, but then, when it gained the status of the Free City of Krakow (1825–1846), it was subjected to a number of restrictive and harassing acts from the “protector” powers. In 1848, Krakow was again incorporated into the Austrian Empire, but after many years it gradually became a self-governing body. It was the beginning of another golden age for the University, which had been renamed the Jagiellonian University in 1817.

The number of chairs increased threefold, so that by the last academic year before the First World War there were 97 of them, while the number of students in the same year was over 3,000. They were mostly male, but in 1897 the first female students were admitted to study pharmacy. They were gradually accepted by other faculties; the last of them to admit women was the Law Faculty in 1918.

After Poland achieved independence in 1918, the number of Polish universities increased from two (Krakow and Lvov) to five, as the universities in Warsaw and Vilnius were restored and the university in Poznan was founded. The academic staff of those schools was largely drawn from the resources of the Jagiellonian University. In the interwar years, Krakow University was considerably expanded. New departments were established, such as the Department of Pedagogy and the Slavic Department in the Philosophy Faculty, and the Physical Education Department in the Faculty of Medicine. However, many political conflicts between students of widely different political views often resulted in violence. The Senate of the Jagiellonian University repeatedly protested against the authoritarian rule of the government, particularly against the trial of opposition politicians at Brest in 1931, as well as against limiting the Universities’ autonomy. The Great Depression in the years 1930–1934 severely affected the finances of the young Polish state, which resulted in drastic cuts in expenditure on education.

The Jagiellonian University was dramatically affected by the German occupation of Poland: 144 University staff were arrested by the Gestapo, together with some students, 21 professors of the Academy of Mining and others, and sent to a concentration camp. In total 183 persons were imprisoned. The University was closed, its property dismantled, destroyed, looted, or sent to Germany. The University suffered losses also from the Soviets. Among the Polish prisoners of wars (POWs) murdered at Katyn and Kharkov were 14 Reserve Officers, University teachers, and graduates. Yet the other university staff resolved to persevere in the face of adversity. University courses were taught in a clandestine way, flaunting the strict Nazi ban on all but the most basic education. During the war period this underground university had about 800 students.

At the end of the Second World War, lectures began in February 1945, with more than 5,000 students registering. It appeared that this was the period of both reconstruction and rapid expansion. The first three postwar years were promising. Many academicians who had been forced to leave Lvov and Vilnius or those who could not return to Warsaw, virtually flattened by the war, found employment at the Jagiellonian University.

However, the year 1948 marked the beginning of the worst period in the University’s postwar history. Stalinism cast its ominous shadow on higher education. The Polish United Workers’ Party was in full control of every aspect of university life. Some professors were dismissed. The great change that came with the end of Stalinism in 1956 affected the University, as it did the whole country. The professors who had been dismissed were allowed to resume their jobs, and the University self-government was restored, the government, however, reserving the right to extensive control, particularly concerning academic promotion.

In 1968, students at the University were actively involved in political protests against the regime, which was followed by repressive measures against the most active protesters and some of the staff, particularly those of Jewish origin. Some academicians decided to emigrate from Poland. Still, when compared with the situation at other universities, repressive measures at the Jagiellonian University were considerably limited. This was certainly due both to the University authorities, who firmly defended the fundamental principles of academic ethics and cooperation, and to virtually all the staff.

The ancient Jagiellonian University, covered with the moss of centuries, today is a young, innovative place. In 1999, the Research Centre for the Life Sciences was opened, and in 2002 this was followed by the opening of the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology building, with the most up-to-date scientific and technological infrastructure in Poland, and the Institute of Environmental Protection. In 2005, the new site for the Institute of Geography and Spatial Management was opened. The infrastructure at the very center of Cracow is also being transformed and modernized—in 2005 the Auditorium Maximum was opened. Technological and Academic Incubator of Technology Park specializing in the Life Sciences was switched on in May 2006. In October 2006, the Jagiellonian University CMs Faculty of Medicine opened its Lecture–Conference Centre.

Vision, Mission, and Core Values of Academic Ethos at Jagiellonian University

On the first page of the Statute of Jagiellonian University enacted on June 7, 2006, there is a statement that clearly emphasizes its aged cultural heritage as follows:

The Jagiellonian University—Alma Mater Jagellonica—was established by King Kazimierz the Great, renovated by King Wladyslaw Jagiello. University continues its ancient heritage of service for science and education through carrying out scientific research, constant quest for the truth and promoting it with sense of moral responsibility for the Nation and the Republic of Poland.

In its activity the University lives up to a principle of PLUS RATIO QUAM VIS.2

In the same document within a section named General Terms there occurs also a mission statement of Jagiellonian University:

The mission of the University is to educate foster culture in society and carry out scientific research. Due to its own activity and personal example of academic society members, the University prepares mature, self-reliant people for the home country, who are ready to solve everyday problems, which the modern life brings up. The University not only takes part in development of science, health protection, art and other fields of culture but also educates and up-brings students and academic personnel according to ideas of humanism and tolerance, spirit of respect for truth and hard work, the law and justice, human dignity, patriotism, democracy, honour and responsibility for Society and Homeland.3

The core principles statement for performance of this organization include freedom of scientific research and promoting creative scientific; this is expressed in the unity of science and education, or operating by keeping constant contact with local and foreign research institutes, community centers, education and didactic institutions, cultural and economical units, and health care centers.

The Jagiellonian University Senate adopted the University Code of Ethics on June 25, 2003 to set forth the principles and values necessary to guide and govern the academic community.4 Science and higher education are being deeply restructured in Poland. There are still some crisis phenomena typical for the economic structural change of a state. Structure and conditions for a university’s performance are changing. Private higher education has developed to the great extent, and next-to-free graduate and undergraduate studies there extended various forms of highly charged educational services.5 Scientists, especially professors, take jobs at many schools, which influences their relations with their alma maters and the level of their dedication to scientific research. Not all resist the temptation to act in an unscientific way (participating in politics, elaborating expert’s reports ordered by private companies, diffusing views in mass media that hardly qualify as “scientific”).

Detrimental phenomena accumulate in scientists’ awareness, motivation, activity, and ethical attitudes, leading to an overall decline in standards and morale. Such a decline in ethics has a direct impact on the health of academic research and the well-being of the entire nation. The University Code of Ethics stands through time as the light of reason over force, guiding the conduct (and censuring the misconduct) of academicians in all fields of study. Their reflection in the attitudes and activities of the members of the university community support the sustainability of key moral values shaped by a long-standing university tradition.6

The core values of Jagiellonian University are7

• Truth, which is the fundamental of a scientist. It includes discovering the truth and formulating views and theories that are true as well as announcing and bringing up academic students.

• Responsibility for scientific technique, the whole discipline as well as institution and environment and for the way of exploiting scientist’s authority beyond the university and science, including application of research results in practice.

• Good will—the duty of every master is to inspire other masters and to transfer the widest, most reliable, and clearest message of the whole body of knowledge to lecture listeners and publication readers. It is also the creation of a “good job” atmosphere that encourages energy and enthusiasm of all participants of academic life, the atmosphere that would be free from small-mindedness, discouraging criticism, competitive hurry, and false simulation of scientific activity.

• Justice—the higher school is a school of justice, practical learning of its recognition, defining, application, and respect for its principles.

• Reliability—science is a domain of extraordinary solidity, precision, reliable attitude to facts, achievements of predecessors, and precise language used for creating theories and knowledge diffusion.

• Tolerance—no period, school, method, or even the brightest mind should hinder the course of true science. Cognitive wisdom requires caution and the recognition of the importance of diversity, its understanding, and estimated acceptance or tolerance. Tolerance is understood as the cautious listening to the opinions of others, even to those that are contrary to the binding ones and especially contrary to our personal ones.

• Loyalty—Loyalty to the mother academic community may be expressed in everyday conduct as well as in special moments that require courage, commitment, and persistence and an abdication of private interest and opportunism. Loyalty may be expressed by the labor discipline and support for the democratically chosen authority as well as by the reliability toward colleagues, students, and all members of the academic community by helping with joint initiatives, especially those supporting the university’s and its members’ prestige.

• Independence—Scientific creativity is a process of two actions: of transforming the achievements of predecessors and present authors and of contributing the effects of research results that were independently prepared, conducted, and elaborated. Any violation of the principle of independence such as plagiarism, cryptoplagiarism, or autoplagiarism is the violation of the fundamental rules and the idea of the science mission.

• Honesty—It is connected with the attitude to other people, public issues of any public range, and the level of personal responsibility, and within the scientific and didactic activity—the application of clear and unambiguous criteria of conduct and evaluation.

• Dignity—It provokes the internal strength that does not allow withdrawal from personal beliefs or ethical principles or let the person give in to pressure, comfort temptations, and false aspirations for honors and awards. Dignity is not the privilege of any chosen social group, environment, or position. The equal right to dignity is possessed not only by the respected professor, but also by the scientific worker, or by a secretary, librarian, storekeeper, or by the worker of cleaning services.

• Freedom of science, freedom of scientists—ethical values arise, are in force, and express themselves openly within the communities of free people. Freedom is the precondition for the choice of values, searching for them, and their subsequent creation. The subjective freedom of scientists is necessary here. Those scientists conducting in accordance with their mind, experience, and individual conscience are able to develop fully their talents to discover and ability to defend the pressure of negative external factors or internal enslavement.

The Code of Good University Practices supplements the Jagiellonian University Code of Ethics; it was compiled by the Polish Rectors Foundation and passed by the Plenary Assembly of the Polish Rectors Conference on April 26, 2007.8 In this document are formulated fundamental principles and good manners in leading a university that go beyond the rules of common law and other legal regulations referring to higher schools’ performance.9 These principles include: public service; impartiality within public affairs; autonomy and responsibility; power sharing and balance in the higher school; transparency; dignity, respect, and tolerance; and the principle of universalism of research and education.

The document also includes sections referring to good practices of a rector’s conduct, such as: responsibility for university’s development; the culture of senate sessions; avoidance of decisions concerning the Rector’s own issues; education quality concerns; respect for the university’s tradition; and the Rector’s cooperation with his or her predecessors. Moreover, some sections referring to good practices of senate conduct are present in this document. They take into considerations issues such as cooperation between senate and faculty councils, student participation in senate sessions, responsibility for programs of education, ways of voting, and evaluation of a Rector’s activity.

Institutionalization of Academic Ethos Core Values at Jagiellonian University

Jagiellonian University is immersed in tradition. This tradition and its results, such as various rituals, ceremonies, and architecture symbols, express core values of this higher school. Academic customs embedded in the 600-year history of Jagiellonian University make its values as vibrant as today; they are bequeathed to subsequent generations of people managing Jagiellonian University.

In the process of maintaining, enacting, and directing Jagiellonian University’s core values, there is a wide range of ceremonies, rituals, architecture symbols such as the external architecture of campus buildings, monuments, logos, seals or colors, or the physical symbols as a dress code (ceremonial gowns), rings, symbols of prestige, symbols of hierarchy or social position as, for instance, presidential costume, chain, mace. Below, I will characterize briefly some of them.

Jagiellonian University preserves and promulgates its many rich customs and traditions. Regular and special academic celebrations are the proof for what are these great academic traditions and customs.10

According to the custom Rector, Deans, professors, and people with a degree of doctor habilitated have the privilege to wear traditional gowns and to carry an insignia of their authority. The style and colors of the gowns and the type of insignia correspond to the customs formed at the University. The Rector insignias are: a scepter, a chain, and a ring.11

The colors of particular faculties are

• black for Law and Administration;

• claret (deep red) for Medicine;

• claret with blue rim for Pharmacy and Medical Analysis;

• claret for Health Care;

• silver for Philosophy;

• blue for History;

• navy blue for Philology;

• navy blue with blue rim for Polish Language and Literature;

• purple for Physics and Astronomy;

• purple with blue rim for Applied Computer Science, Mathematics and Computer Science;

• yellow for Chemistry;

• green for Biology and Earth Sciences;

• brown for Management and Social Communication;

• carmine for International and Political Studies;

• ecru for Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology.

Life of the academic community is enhanced by specified rituals and ceremonies that come from the fifteenth century and are cultivated in modern times. They not only create a sense of community among participants of Jagiellonian University’s academic society but are also the basis for the cultivated cultural identity of the entire university.

The most significant ceremonies and rituals of academic tradition that are currently practiced at Jagiellonian University include: May 12 is when the school commemorates the founding of the Jagiellonian University and is a holiday for the whole academic community; November 6 is when the school commemorates the day when the professors and other members of the university community were imprisoned by Nazis in 1939 (it is the Commemoration Day about Them; and it is also the Commemoration Day about All Deceased Workers of the University); new PhDs promoting, or awarding honorary doctorates (doctorates honoris causa); and finally, the day of inauguration of the new academic year (usually October 1). On this day, Krakow inhabitants and tourists may see the ceremonial parade of professors from the oldest Polish university marching from the academic St. Anna Collegiate Church and Collegium Maius edifice to the Auditorium Maximum (before the year 2005 the march used to end in the Collegium Novum).

Although during the past 640 years the Almae Matris inauguration ceremonies of this kind did not always take place, they date back to the very beginning of the Jagiellonian University. The first ceremony of this kind, information about which has been preserved in documents, is connected with the University’s renewal. It took place on Monday, July 26, 1400 at the place of today’s Collegium Maius. Maciej Radzyminski—a historiographer of Krakow University from seventeenth century—created an imaginary description of this first inauguration. He was inspired by the ceremonies typical for his times (over 200 years later). The description illustrates the ceremonial parade of eminent hosts and professors in their gowns marching from the Wawel Castle, along the Royal Way to the Market Square, and then to Collegium Maius. There is no mention of this march in sources dated for 1400, but in the mid-seventeenth century, such parades were the element of the old academic tradition. They obviously result from the religious processions, which is why its participants were arranged according to their status—from students to the Rector holding the highest office (so-called ordo canonicus), who was preceded with people carrying the Rector’s mace (named pedli).

Other parts of the religious processions included professors wearing garments derived from the higher clergy. When the Collegium Novum was erected in Krakow in 1887, it became the place of ceremonial inaugurations of the successive academic years, but the march still started from Collegium Maius, and it has not changed over time. The constant element of the inauguration (apart from the Rector’s report of Almae Matris activity of the precedent year) is a lecture by a professor from the university who is widely respected in the scientific community for his or her achievements, as well as the ritual of matriculation of chosen representatives of new students. Moreover, this ceremony always ends with singing a song, Gaudeamus Igitur (in Anglo-Saxon countries known as De brevitate vitae), what, for over the past 100 years, has been realized by the academic choir of the Jagiellonian University.12 During the ritual of matriculation, new students and doctors are included into the academic community, and they take the following oath:

Aware of the great tradition and accomplishments of the Jagiellonian University as well as the responsibilities of a member of the academic community, I hereby solemnly swear:

• I will seek the truth, the fundament of all science;

• I will gain lasting knowledge and abilities for the good of my Homeland;

• I will uphold the norms, social standards and traditions of the University;

• I will cultivate the good name of our University and the honor of its students.13

The oath indicates that the civil duty of a student is to respect tradition and customs of the University and take care of its image.

A statute of the Jagiellonian University specifies the rights and duties of its employees. The basic duties of research and didactic employees include educating and up-bringing students, supervising students’ work (taking into account merit and methods), conducting scientific research and developmental works, developing scientific or artistic creativity, and participating in organizational work at the University. Moreover, employees of the professor or doctor habilitated degree have a duty to educate the scientific staff. All the academic teachers are obliged to comply with the University’s System for Education Quality Improvement and adopted education courses.

Core values of Jagiellonian University’s academic ethos are expressed within its ceremonies, rituals, and documents of the school such as statutes, codes of academic values, or codes of good manner in higher schools; symbols also illustrate what the core of Jagiellonian University’s cultural identity is, namely its values constituting academic ethos.

When describing Jagiellonian University’s tradition, it is necessary to mention the edifice of Collegium Maius:

Collegium Maius, situated at the corner of St. Anna and Jagiellonska Streets, is the oldest university edifice in Poland. Its history goes back to the year 1,400, when King Wladyslaw Jagiello purchased the Pecherz family’s corner house and donated it to the University. The actual walls of the Pecherz house have been preserved in their foundations and on the side overlooking Jagiellonska Street. This is easily traceable by observing the wild-stone composition, so typical of the fourteenth century. The house was not large and hardly could hold the University activities. During the fifteenth century Collegium Maius was extended. The University was able to purchase the houses contiguous to the College and to combine them into a harmonious whole, complete with a courtyard enclosed with a ring of arcades, interrupted with the professor’s staircase, leading up to the first-floor balconies.

On the ground floor there were lectoria, i.e. lecture rooms, low-vaulted, dark and often wet rooms. On the first floor were the Library (added c.1515–1519), the Stuba Communis (refectory for Professors), the Treasury rooms and the Assembly Hall. The Professor chambers were located all over the building.

Up to the second half of nineteenth century the appearance and interior arrangements of the Collegium Maius didn’t change much. The neogothic reconstruction in the years 1840–1870, changed the original face of the Collegium and transformed it into the University Library, which used the building up to 1940. Between 1949 and 1964, on the personal initiative of Prof. Karol Estreicher Jr., the whole building underwent a major refurbishment and conservation, shedding all superfluous neogothic additions, that effectively blurred the austere elegance of its original structure. It this time the Collegium Maius was also designated as the seat of the Jagellonian University Museum, home to ancient university collections, including the collection of the old scientific instruments.14

After its thorough renovation, the lower levels of the Collegium Maius became a place for conferences in the so-called “Casimir the Great Hall,” and for meetings “At Pecherz” café; additionally, all the rooms may be used as exhibition halls. It also has a representative function as the museum hosts the most important academic conferences and Jagiellonian University Senate sessions. It has been visited by the most eminent university guests including John Paul II, Queen Elisabeth II, and the emperor and empress of Japan.

Collegium Maius is not the only museum located in the Jagiellonian University’s buildings as evidence of its long tradition and history. The Zoological Museum was established in 1782 as the Studio of Natural History, and the Jagiellonian University Museum of Pharmacy founded in Krakow in 1946 is the largest institution of its kind in Poland and one of the few such museums in the world. Jagiellonian University possesses one of the oldest collections gathered since 1782, and in 1900, as an initiative of Professor Walery Jaworski, the Museum of Faculty of Medicine was founded at the Jagiellonian University.15

Jagiellonian University has its emblems, seal, flags, and songs. Two crossed maces emblazoned on a blue shield topped with a crown adorn the University coat of arms. A separate coat of arms with a picture of Saint Stanislaw over a shield and a crowned white eagle on a red background is used for special celebrations and also serves as the primary seal of the Jagiellonian University. The University flag has crossed gold maces topped with a crown placed in the background. During academic celebrations, Gaude Mater Polonia is traditionally performed.16

Conduct compliant with the values of academic ethos are appreciated and rewarded at the Jagiellonian University. The most prestigious honor at the Jagiellonian University is the award of honorary doctorate (doctorate honoris causa). Awarding honorary doctorates (doctorates honoris causa) dates back to the 1810s and is modeled after the practices of German and Austrian universities. In April 1815, the Jagiellonian University referred to those universities when it requested from the educational authorities in Warsaw the right to “award doctorates to the men of letters distinguished for their wise and valuable writings.” The doctorates were called honorifica (not to be mistaken for those awarded under the ordinary procedures).17 The first honor of this kind was awarded in 1816 to Feliks Bentkowski and Paweł Czajkowski; in 2011, eminent persons such as Gaetano Platania (the historian with great achievements for the research on history of Poland), Peter-Christian Müller-Graf (one of the most eminent German lawyers of these days), Thomas L. Saaty (one of the most eminent American mathematicians), and Hans Joachim Meyer (a widely respected authority in general surgery) were honored.18

Other honors at Jagiellonian University include the Pro Arte Docendi Award, given to eminent University teachers for the high quality of their teaching, their mastery of imparting knowledge to their students, use of innovative methodologies of teaching, outstanding educational achievements, individual work with top students, and cooperation with student societies. The award, presented at the convocation of the new school year, may be given to individuals or groups.19 Moreover, the Merentibus Medal may also be awarded for services rendered at the University. It can be given either to a person or to an institution, from both Poland and abroad. In certain instances, the medal can be awarded to University staff members. Following a proposal from the Rector, the decision to present someone with the medal is undertaken by the Jagiellonian University Senate. An entry into the Book of the Awarded justifying the decision is made each time the medal is awarded. The Rector presents the medal during University ceremonies. At the ceremony, the medal winner also receives a special certificate, and the entry from the Book of the Awarded is read aloud.20

However, it is not only the past and tradition that live on at the Jagiellonian University as authorities of this higher school care for cultivating fresh values of academic ethos and creating a robust academic community through various initiatives. One example of such activity taken by the Rector for creating the sense of membership of this outstanding, aged university is a picnic day for Jagiellonian University’s employees. It is part of tradition at the Jagiellonian University that every May the Jagiellonian University Rector invites his employees for an annual picnic and provides attractions such as games, snacks, gifts, and dance classes.21

Fulfilling its mission, the Jagiellonian University does not forget its role in natural resources preservation for the future generations. Evidence for such conduct may be the initiative named “eco style student,” which is aimed at promoting and teaching water and energy conservation. Similar instances for actions taken by the Jagiellonian University’s authorities and academic community that fulfill university’s mission and enact values of academic ethos are numerous and would provide enough material for more than a single book.

Having studied and analyzed the above examples, it may be categorically stated that the Jagiellonian University is an excellent model of the ideal balance between modernity and tradition, today’s customs and those from the fifteenth century. Moreover, the university may be a kind of guidebook describing the way for cultivating values of academic ethos for centuries without the loss of the most important element of its identity and culture—its core values, and at the same time for changing everything else at the university. It is an exemplar that should be followed as it proves that the source for persistence and development of higher schools is their loyalty to academic values and incessant process of their enacting and protection for and on behalf of the successive generations.

Case Study 2: Hamline University

Name: Hamline University.22

Country: United States of America (Saint Paul, Minneapolis, MN).

Date of foundation: In the year 1854, named after Bishop Leonidas Lent Hamline of the United Methodist Church.

Motto: Looking back, Thinking forward.

Form: A private liberal arts college.

Rector/President: Linda N. Hanson.

Structure: Hamline University includes the following five schools and colleges: College of Liberal Arts, School of Education, Graduate School of Liberal Studies, Hamline University School of Law, and Hamline University School of Business.

University colors: Burgundy and gray.

Enrollment: Nearly 5,000 students, including 1,866 undergraduate students.

Employees/Administrates: No data.

Alumni: No data.

Notable alumni: Barb Goodwin (member of Minnesota State Senate), Martin Maginnis (member of US House of Representatives), Van Tran (current member of California State Assembly), Kerry Trask (candidate for Wisconsin State Assembly), Tom Dooher (president of Education Minnesota, AFT, NEA, AFL-CIO), Anna Arnold Hedgeman (civil rights leader and Hamline’s first African-American graduate), Gordon Hintz (member of Wisconsin State Assembly), Yi Gang (deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China), Duane Benson (American football linebacker), Carl Cramer (professional football player), Lew Drill (former professional baseball player), William Fawcett (actor), Coleen Gray (actress), Paul Magers (television news anchor), John Bessler (professor of law), Arthur Gillette (surgeon), John Kenneth Hilliard (academic and Academy Award recipient), Robert LeFevre (libertarian theorist), Deane Montgomery (prominent mathematician and recipient of the Leroy P. Steele Prize), Dwight D. Opperman (chairmen of Key investments and one of Forbes 400 richest Americans), Max Winter (former part owner of Minneapolis Lakers and Minnesota Vikings).

Brief History:

Hamline University is Minnesota’s oldest university. Named in the honor of Leonidas Lent Hamline, a Methodist bishop who donated the funds, Hamline’s first home was in the town of Red Wing in what was then the Territory of Minnesota.

The first classes were held on the second floor of the village general store. Classes were in the second term when students moved into the Red Wing building in January 1856. Seventy-three students enrolled at Hamline in the opening year.

Hamline graduated its first class in 1859: two sisters, Elizabeth A. Sorin and Emily R. Sorin, who were not only Hamline’s first graduates, but also the first graduates of any college or university in Minnesota.

Three courses of study were open to candidates for a degree:

• The “Classical Program”: Greek, Latin, English language and literature, and mathematics;

• The “Scientific Course”: included the studies of the classical program but substituted German for Greek and Latin;

• The “Lady Baccalaureate of Arts”: a separate course for women, omitting Greek and abridging Latin and mathematics while introducing French and German and the fine arts.

On July 6, 1869, the Red Wing location was closed. It is believed that the building was torn down around 1872.

Building operations for the new University Hall began in 1873, but the Depression had overtaken the planners and there were repeated postponements and delays. The doors finally opened on September 22, 1880, and Hamline’s history in Saint Paul began. The catalog for that year lists 113 students, with all but five of them preparatory students.

Tragedy shocked the campus on February 7, 1883 when the new building, barely 2.5 years old, burned to the ground. With frontier fortitude, the plans for a new University Hall were prepared. Eleven months later, the new structure, the present Old Main, was dedicated in the presence of a throng whose carriages were parked all over the campus.

During the First World War in April 1917, the students responded to the call to duty in a variety of ways, seeming to grasp the issues at stake and the parts that would be required of them in the war. In the fall of 1918, a unit of the Students’ Army Training Corps was established at Hamline and almost every male student became an enlisted member. The Science Hall was used for military purposes, with the basement becoming the mess hall, and the museum and several classrooms being marked for squad rooms and sleeping quarters.

A new venture was launched in 1940 when Hamline University and Asbury Methodist Hospital of Minneapolis established the Hamline-Asbury School of Nursing, offering a 5-year program (later a 4-year program) leading to the degree of bachelor of science in nursing.

A flood of veterans entered or returned to college after the Second World War under the G.I. Bill of Rights. The first reached the campus in the fall of 1946, when registrations passed 1000 for the first time.

The School of Nursing was discontinued in 1962 following the decision to concentrate resources and staff on the liberal arts program.

During the 1960s, Hamline began to address matters such as the racial diversity of its students and faculty, institutional racism, and the education of culturally disadvantaged students. Hamline felt the impact of deepening racial turmoil during this decade. In 1968, black students on campus founded PRIDE—Promoting Racial Identity, Dignity, and Equality.

The university launched an innovative MBA program in 2008, aligned undergraduate and graduate programs in School of Business (including business, management, public administration, and nonprofit management) and School of Education, created centers for Business Law and Health Law, and created an in-residence MFA in Young Adult and Children’s Literature.

In 2008, Hamline University expanded to a 33,000-square-foot location in Minneapolis and now offers master’s level programs in business and education. Hamline has established a relationship with the United International College, the first liberal arts college in mainland China, and the Shanghai Institute for Foreign Trade.

Vision, Mission, and Core Values of Academic Ethos at Hamline University

In 2006, Dr. Linda N. Hanson, Hamline University’s 19th president, decided to lead “the university through the development of a comprehensive, university-wide strategic plan, Creating Pathways to Distinction, which describes Hamline’s academic vision and strategies to innovate in the tradition of liberal arts and professional education; to be dynamic and actively inclusive; to be locally engaged and globally connected; and to invest in the growth of persons.”23 Hamline built on this in 2006–2007 with a plan that fully focused on its mission, values, and goals for the future. This innovative program, Creating Pathways to Distinction, involved more than 200 trustees, faculty and staff members, and students. The Hamline University community looked at its existing system of education and determined how to create a stronger, more dynamic system that would be more timely, more sensitive to needs, and ultimately would benefit all in the Hamline community24. In the Hamline University Strategic plan for 2007–2012, as well as in the updated version of this document from 2011, we may find the following statements of vision, mission, and core values of Hamline University.

Vision of Hamline University:

To become a dynamic, learning-centered university rooted in the tradition of liberal education, locally engaged and globally connected, and dedicated to the personal and professional growth of every member of our diverse community.25

Mission of Hamline University

To create a diverse and collaborative community of learners dedicated to the development of students’ knowledge, values and skills for successful lives of leadership, scholarship, and service.26

Core values of Hamline University

Hamline University recognizes its roots in the traditions and values of the United Methodist Church, and aspires to the highest standards for

1. Creation, dissemination, and practical application of knowledge.

2. Rigor, creativity, and innovation in teaching, learning, and research.

3. Multicultural competencies in local and global contexts.

4. The development and education of the whole person.

5. An individual and community ethic of social justice, civic responsibility, and inclusive leadership and service.27

Institutionalization of Academic Ethos Core Values at Hamline University

The identity of the Hamline University is deeply rooted in tradition and values of United Methodist Church. The church and army are the oldest organizations that are managed with the use of core values. So it is not surprising that Hamline University has taken the best practices of implementing values for organization’s identity creating through its tradition and identity. Immersion of University’s identity within the values of United Methodist Church as well as its history full of military service made an institutional pattern of core values for this university.

Academic community members in Hamline University participate actively in the process of core values redefinition, formulating declarations of the university’s vision. University leaders are also aware of the fact that in order to make those written vision and mission statements feasible, core values as the core of university’s identity need to reflect strategic directions and objectives.

At Hamline University, its identity, initiatives, and inspiration are built upon a solid foundation of a clearly defined mission, sharply rendered values, and mature vision.28

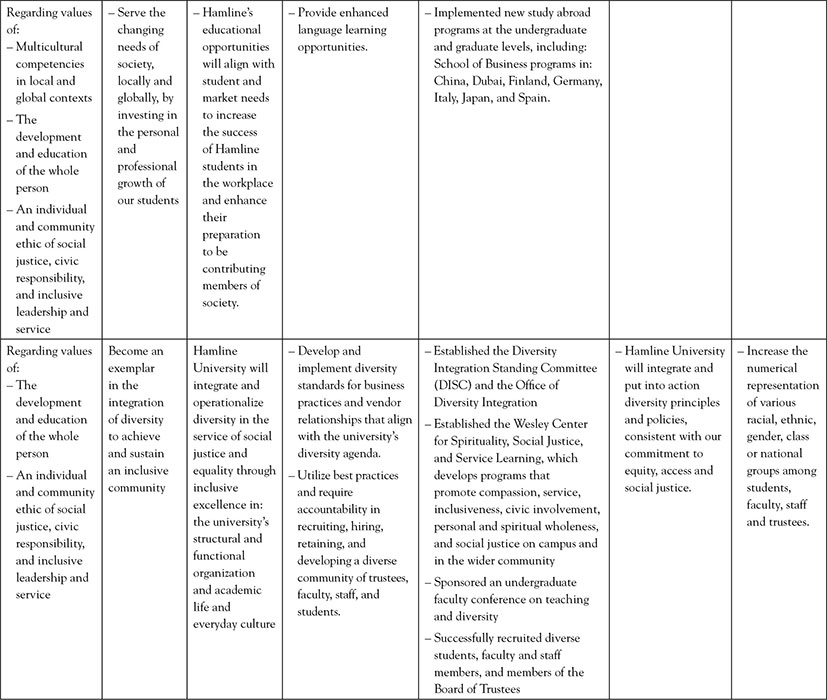

Table 8.1 presents the way in which core values of the Hamline University are reflected in strategic directions and initiatives for their realization in this university. It also indicates the achievements in core value enactment at Hamline University in the past 4 years. Moreover, Table 8.1 is evidence that through personal and collective efforts, Hamline University was able to achieve its objectives of enacting core values.

Table 8.1. Reflecting core Values of the Hamline University in Strategic Directions and Initiatives for Their Realization

Source: Author’s own study based on: Creating Pathways to distinction. Hamline University Strategic Plan 2011. Update and Hamline’s Strategic Plan. Pathways 20 2013–2017.

Hamline University has also elaborated on an array of tools in the form of policies and procedures that enable the school to fulfill objectives and tasks for its core values enactment. Those documents are accessible at the university’s website as faculty/staff/student policies and handbooks. Particular attention should be paid to the legibility of its location in particular webmarks “resources for”: faculty and staff, current/admitted students as well as families/parents, and veterans.

Among the various policies for faculty and staff, the Diversity Policy stands out, where we can read:

Hamline University commits itself to inviting, supporting and affirming cultural diversity on the campus. All university programs and practices, academic and co-curricular, shall be designed to create a learning environment in which cultural differences are valued.

To ensure the achievement of these policy goals, Hamline University is committed to:

Encouraging all organizations to have as part of their constitution and by-laws, a cultural diversity policy that states explicitly the organization’s commitment to fostering cultural diversity on campus;

• Encouraging inclusiveness in all organizations while respecting the different needs of organizations composed of groups that have been or currently are denied equal opportunity.

• Developing and maintaining academic/co-curricular programs and university climate that promises a responsible, civil and open exchange of ideas.

• Educating all members of the campus community about diversity and forms of discrimination, such as racism, sexism, and homophobia.

• Maintaining a respectful environment free from all forms of harassment, hostility and violence.

• Recruiting and working to retain students, staff and faculty who are members of historically or otherwise under-represented groups.

• Providing the necessary financial and academic support to recruit and retain diverse students, faculty and staff.

• The University’s Cultural Diversity Committee shall act as a resource for the implementation of this policy and shall report annually to the President and the University Council. The President shall ensure that procedures are developed to implement this policy. The procedures shall include defined terms and ideas to assist organizations in implementing this policy.29

Its specific supplement addresses discrimination of any sort. The Harassment Policy encompasses all groups (faculty, staff, and students) in the Hamline University community. It starts with a declaration that:

Hamline University will not tolerate harassment, discrimination, or retaliation based on race; color; gender/sex; ethnic background; national origin; sexual orientation; gender presentation; marital, domestic partner or parental status; status with regard to public assistance; disability; religion; age; or veteran status in its employment or educational opportunities.30

There is also a clearly defined policy of strategic objectives and methods for their realization that is a consequence of the vision, mission, and core values.

Hamline’s mission is “to create a diverse and collaborative community of learners dedicated to the development of students’ knowledge, values, and skills for successful lives of leadership, scholarship, and service.” The strategic plan identifies as one of its goals that of becoming “an exemplar in the integration of diversity to achieve and sustain an inclusive community.” Strategic Direction, 4. Discrimination, harassment, or retaliation designed to silence, stigmatize, marginalize, or exclude any individual based on his or her inclusion in a protected class as identified below is incompatible with the University mission and vision to educate, to seek truth, and to sustain an inclusive community.

Students of Hamline University are also supported by the university’s authorities and administrators with valuable documents that serve as independent guidelines for their ethical decisions and actions aimed at studying the unique identity of Hamline University that is based on its core values.31

Undergraduate and graduate students have a number of relevant policies and procedures that should be obeyed if the students want to be successful participants of academic community at Hamline University. The basic document for each student is the Student Handbook 2011–2012, which addresses key topics, such as Hamline’s mission, governance and laws, principles of community, full services, graduate student policies, undergraduate student policies, policies for resident students, student organization information, and other questions and concerns.32

Hamilton University elaborated on a wide orientation program for admitted students that includes:

Piper Preview is the first of two required orientation programs for all incoming first-year students. During this 2-day/overnight program, you and your parents/family members will get the opportunity to

• Meet your New Student Mentor (orientation leader) and other incoming Pipers.

• Learn from faculty and staff what it takes to be academically successful.

• Choose your classes and register online.

• Speak with offices and departments to get all your questions answered.

• Get a sneak peek into life on campus with entertainment and a night in the residence halls.

• Leave with a feeling of pride and confidence knowing that Hamline was the right choice for you.33

• Piper Passages is the second required orientation program for all first-year students. A few days before classes start, students who plan on living in the residence halls will move in, commuter students will have a Commuter Student Pre-Orientation Program, and parents and family members will also participate in a variety of orientation sessions.34

Parents and guardians of students are also treated at the Hamilton University as integrated and important parts of the academic community. Interesting and recommendable initiatives include the Parent Network and Parent E-Newsletter.

The Parent Network is a representative group of the Parents Association and acts as a liaison between the University and the parents. And as a parent, you are already a member!

The Parent E-Newsletter is an excellent resource, providing updates and stories about life on campus, Hamline students, faculty, and other events and useful information about Hamline.35

Hamline University is proud of its long history of military service that started during the Civil War. In honor of the women and men of the military, the university is fully dedicated to offering veterans a superior academic experience.36 Hamline exhibits its pride in its veterans by helping them make the transition from military to school smooth, accessible, and richly rewarding.37

Hamline University includes its graduates as the custodians of Hamline University’s values:

Hamline owes its strong reputation for academic excellence and moral values to the leadership, generosity, and success of its alumni. It is thanks to alumni and their belief in John Wesley’s quote, “Do all the good you can, in all the ways that you can . . .” that Hamline has such beautiful and technologically advanced facilities, scholarships that allow students to reach their academic potential, and inspiration on how to live a life of leadership, service, and scholarship.38

All the mentioned policies, procedures, and initiatives for enacting core values at the Hamline University are supported by the Office of the Ombudsman. This office has existed at the Hamline University since 1998 as Ombuds services on a part-time basis, and since 2005 as Hamline University’s Ombudsman Office.

The Ombudsman is a confidential, neutral and informal resource to whom students, faculty and staff can bring any university-related question, concern, or conflict. The Ombuds is an alternative to existing university problem-solving services and can help to surface concerns, resolve disputes, manage conflict, explain of University’s policies and procedures, and educate individuals in more productive ways of communicating. The Ombudsman can function in a number of ways: as an impartial listener, as a resource for assistance, as a confidential advisor, as a facilitator of discussions or meetings and as an informal mediator or negotiator. Communications with the Ombudsman are entirely confidential, except in the case of imminent risk of serious harm. This confidentiality allows visitors to explore options and generate possible avenues for resolution without involving formal channels.

The Ombudsman Office is not an office of notice for the university.39

Hamline’s Ombudsman adheres to the Standards of Practice and Code of Ethics of the International Ombudsman Association. The Ombuds Office is confidential, neutral, informal and independent.40

Having analyzed the values of academic ethos of Hamline University, there emerges an impression that the value that best describes the spirit of the university and that interprets its vision and mission of the United Methodist Church is the diversity:

This diversity is not merely a characteristic of Hamline, but an integral part of its identity and values. It’s who we are, what we do, and how we see the world. Hamline isn’t a place where you “fit in,” conforming to the Hamline mold. Rather, Hamline “fits in” you, welcoming your unique contributions and valuing who you are.41

Diversity at the Hamline University is not just a beautiful decoration, a proper declaration. It is a deeply rooted value in the academic community supported with tools for particular policies, procedures, and initiatives for its institutionalization. It is a carefully cultivated and deeply shared core value.

It is worth noting that in 2002 Hamline University formulated a definition for the term “diversity” that not only draws on its own policies and definitions but also turns a keen eye toward the concerns of those outside the community; case in point, by examining definitions from the University of Central Florida:

Diversity refers to the variety of backgrounds and characteristics found among humankind; thus, it encompasses all aspects of human similarities and differences.42

Authorities at the Hamline University are fully aware that for fulfilling its mission as “a diverse community of learners with students at the center that transforms lives,”43 it is not enough just to elaborate a diversity policy. Policies must be a complete, active, vital collaboration among administrations, schools, and programs.44 That is why at the Hamline University, the value “diversity” is integrated “across five major focus areas”:

Student learning inside the classroom (faculty development and academic affairs);

Students outside the classroom (student affairs);

Faculty recruitment and retention;

Staff recruitment, development, and retention;

External relations and partnerships.45

The Office of Diversity Integration is responsible for all activities within these areas; it supports university programs with a keen eye toward ensuring comprehensive advocacy on behalf of all diversity and equality practices.46 Exemplar activity by this unit includes:

• developing and coordinating diversity-centered events with faculty, staff, and students;

• initiating development and training opportunities;

• supporting innovative scholarly and curricular techniques;

• creating a welcoming campus environment for all students, regardless his or her background;

• maintaining an archive of diversity-related documents and resources;

• developing relationships with organizations beyond the walls of academia in the community at large.47

The University’s authorities do know that communicating a particular value, explaining its meaning, and even creating appropriate infrastructure in a form of policies and procedures is not enough. Implementation of particular value depends not only on the awareness of the value’s essence among members of academic community, but also on their knowledge and capabilities to take particular actions for its implementation.

That is why the Hamline University elaborated and implemented “The Staff Diversity Development Initiative, [which] is a framework for professional development training and educational opportunities that assist Hamline University staff members in

• developing knowledge, awareness and skills for strengthening their work in and with our diverse community of learners and workers;

• supporting student learning, acclimation and success in the university community;

• achieving their individual professional and personal diversity goals as outlined in their annual performance reviews; and

• assisting Hamline University to achieve our diversity goals and aspiration in their respective roles, responsibilities, and units.48

Apart from this, faculty members have support for teaching diversity in the form of pedagogical support, curriculum development, and assessment resources. The Race, Gender and Beyond Faculty Development Program “offers a range of activities from individual consultations, to drop-in reading groups, to workshops, on-going reading groups as well as summer institutes.”49

Hamline University reinforces its experience and knowledge about institutional value of “diversity” among academic community from external organizations:

Since May 1999, Hamline University has been sending a team of staff, students, faculty and administrators to the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity (NCORE) in American Education.50

NCORE’s purpose is to support the development of Hamline-based diversity leadership and Hamline’s teams, in turn, provide on-campus programs tailored to the particular learning needs of our university community.51

Having analyzed the spectrum of activities undertaken at the Hamline University for institutionalization of the “diversity” value, there emerges an impression that the school is replete with diversity. In effect, this university has created a specific culture of diversity. Immersion in an organization that actively fosters such diversity is the best way for this value to become embedded within students. Hamline University constantly offers activities in the form of diversity workshops, programs, and training opportunities that are aimed at helping students prepare to live, serve, and succeed in a diverse university and in the world. The Hedgeman Center for Student Diversity Initiatives and Programs or the Safe Zone Network are two prime examples of this fine attention to diversity.

Authorities at Hamline University also remember that the substantial element of core values maintaining is motivating and rewarding for behavior compliant with them. The choice of awards and distinctions is very impressive in this field. They include awards and distinctions such as Wesley Award for students, staff, and faculty, Diversity Research Award, or the Honorary Degrees.

The Hamline Diversity Research Award is given annually to an undergraduate who demonstrates excellent facility with scholarly research materials to produce a project on a diversity topic.52

On the other hand

Honorary degrees are awarded to outstanding high-achieving individuals who have made contributions in their respective fields, and who live lives that demonstrate the highest ethical integrity and commitment to the greater good. (…)While not all recipients have close Hamline connections, all such individuals exemplify Hamline’s core mission, vision, and values.53

When describing management by values of academic ethos in the Hamline University, we cannot forget that it is the first and the oldest university in the state of Minnesota. Its identity derived from its nearly 200-year-old traditions. This immersion in tradition is visible at every step in the Hamline University, starting from the Hamline Seal that includes three values: religion, learning, and freedom,54 through architecture symbols such as The Bishop Statue, Bridgman Memorial Court, and Hamline United Methodist Church, ending up with stories like these:

This quote from John Wesley is the cornerstone of what Hamline is all about it. It’s recited by the President at the Matriculation ceremony and at Commencement—and a few times in between.

Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.55

and The Piper:

In the 1920s, Hamline athletics were quite successful. As interest in the teams grew, the St. Paul Pioneer Press-Dispatch writers felt that a new team name was needed to replace the traditional name, “Red and Gray.” Suggestions came in, among them “Red Sox,” “Red Legs,” and “Cardinals.” But the suggestion that caught on was “Pipers,” taken from Robert Browning’s poem “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” Throughout the years, students have shown their school spirit by bringing the Piper to life.56

Not all traditions hearken back to older times. In 2005, Hamline’s president Linda N. Hanson decided to “light up Hewitt Avenue” for the Christmas holidays by gathering the community around the Bishop statue and flipping the switch for the many lights adorning the festive tree. Now, holiday celebrations include cocoa, candy canes, and camaraderie during the Annual Tree Lighting Ceremony at the school.

This example not only clearly shows that Hamline University cultivates its identity and its core values through stories from the past but also participates in the process of continually developing those traditions. Authorities not only talk but also listen to what the academic community members are talking about, what jokes and stories they are saying. The University’s leaders choose those that reflect university’s core values.

Through the evidence above, Hamline University clearly shows itself to be a model for managing core values that constitute cultural identity of the university. This identity is a set of core values (its central characteristics) that can distinguish a higher school, not only grounding it in the ideals of university that have come down through the ages but also remaining on the tip of twenty-first century advancements and concerns. Core value management is an important catalyst for the continued success of a higher school. Hamline University has proved that for the past 200 years, it has been excellent in this process.