Chapter 30

Financial Institutions

(c) Types of Financial Institutions

(i) Banks and Savings Institutions

(ii) Mortgage Banking Activities

(viii) Securities Brokers and Dealers

(ix) Real Estate Investment Trusts

30.2 Banks and Savings Institutions

(a) Primary Risks of Banks and Savings Institutions

(b) Regulation and Supervision of Banks and Savings Institutions

(i) Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

(iii) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

(iv) Office of Thrift Supervision

(e) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act Section 112

(i) The Regulation and Guidelines

(iii) Holding Company Exception

(f) Capital Adequacy Guidelines

(i) Risk-Based and Leverage Ratios

(ii) Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 Components

(iv) Capital Calculations and Minimum Requirements

(v) Interest Rate Risk and Capital Adequacy

(vi) Capital Allocated for Market Risk

(ii) Regulatory Rating Systems

(iii) Risk-Focused Examinations

(i) Disclosure of Capital Matters

(j) Securities and Exchange Commission

(k) Financial Statement Presentation

(iv) Commitments and Off-Balance-Sheet Risk

(v) Disclosures of Certain Significant Risks and Uncertainties

(m) Generally Accepted Accounting Principles versus Regulatory Accounting Principles

(p) Loan Sales and Mortgage Banking Activities

(q) Real Estate Investments, Real Estate Owned, and Other Foreclosed Assets

(r) Investments in Debt and Equity Securities

(i) Accounting for Investments in Debt and Equity Securities

(iv) Securities Borrowing and Lending

(t) Federal Funds and Repurchase Agreements

(vi) Loan Origination Fees and Costs

(w) Futures, Forwards, Options, Swaps, and Similar Financial Instruments

(v) Foreign Exchange Contracts

(x) Fiduciary Services and Other Fee Income

(y) Electronic Banking and Technology Risks

30.3 Mortgage Banking Activities

(c) Mortgage Loans Held for Sale

(d) Mortgage Loans Held for Investment

(e) Sales of Mortgage Loans and Securities

(i) Gain or Loss on Sale of Mortgage Loans

(ii) Financial Assets Subject to Prepayment

(i) Initial Capitalization of Mortgage Servicing Rights

(ii) Amortization of Mortgage Servicing Rights

(iii) Impairment of Mortgage Servicing Rights

(iv) Fair Value of Mortgage Servicing Rights

(v) Sales of Mortgage Servicing Rights

(i) Securities and Exchange Commission Statutes

(ii) Types of Investment Companies

(ii) General Reporting Requirements

(g) Investment Partnerships—Special Considerations

(h) Offshore Funds—Special Considerations

30.5 Sources and Suggested References

Bank and Savings Institutions' Regulatory Guidance

30.1 Overview

(a) Changing the Environment

The financial institutions industry has changed significantly in the last two decades. The conventional model of providing and receiving financial services has disappeared in the era since the Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB) Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999. The continuous wave of consolidations in the financial services industry has resulted in fewer but bigger financial institutions, and they are often perceived as being too big to fail. Financial services and products of banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, and brokerage firms that once were distinguishable and whose roles were separated are now consolidated and converged. Regulatory changes and increased global competition have further blurred the lines among depository institutions, mortgage banking activities, investment companies, credit unions, investment banks, insurance companies, finance companies, and securities brokers and dealers.

Global competition has increased as all types of financial services firms conduct business directly with potential depositors and borrowers. Transactions traditionally executed through depository institutions are now handled by all types of financial institutions. Increased global competition has heightened the depository institutions' desire for innovative approaches to attracting depositors and borrowers worldwide. Financial institutions are seeking higher levels of noninterest income, restructuring banking operations to reduce costs, and continuing consolidation within the industry. Consolidation, convergence, and competition derived primarily from deregulation and technological advances have reshaped the financial services industry. The passage of the GLB Act has accelerated the pace of consolidation and convergence in the financial services industry and has raised some concerns that its implementation has created concentration of economic power that would have made it more difficult for government to effectively oversee the industry's activities and strategies in managing risk. Some overriding reasons for the current financial crises are:

- Ineffective regulation

- Greed and incompetence of executives of troubled financial institutions

- Nature of bank lending and investment

- Inadequate risk assessment

- Conflicts of interest financial services activities

This chapter presents an overview of the financial services industry, its role in the economy, types and nature of financial firms and their regulatory framework, financial activities, and related risks.

(b) Role in the Economy

Financial services firms play an important role in our economy by financing individual and business projects, lending to individuals and businesses, and investing in capital markets. Financial institutions can promote economic growth and prosperity for the nation, and their inefficiency can cause significant threats and the uncertainty and volatility in the markets, which adversely affect investor confidence worldwide. This lack of public trust and investor confidence has caused once-prominent Wall Street firms to either disappear or reorganize; for example, Bear Stearns merged with JP Morgan Chase; Lehman Brothers went bankrupt; Merrill Lynch was acquired by Bank of America; and Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs changed their corporate structures, becoming bank holding companies. It appears that the government facilitates the establishment of giant companies (e.g., AIG, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac) to promote its social, economic, and political policies. Executives of these giant companies continuously make high-risk decisions, and while they receive outrageous compensation to make these decisions, lawmakers and regulators have failed to hold them accountable for their excessive risk-taking activities and appetite. These companies became too large to fail; in efforts to prevent their collapse, the government steps in to bail them out at the taxpayers' expense. Financial institutions worldwide have lost more than $1.5 trillion on mortgage-related losses during the 2007–2009 global financial crisis. The failed financial institutions of Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, and Merrill Lynch all played a vital role in the recent economic meltdown, as they all engaged in risky mortgage-lending practices, credit derivatives, hedge funds, and corporate loans.

Financial institutions are essential financial intermediaries in the economy in the sense that they provide liquidity transformation and monitoring mechanisms. Financial institutions in their basic role provide a medium of exchange; however, they may also serve as a tool to regulate the economy. In a complex financial and economic environment, the regulation of financial institutions—directly and indirectly—is used to impact economic activity. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 was passed to minimize the probability of future financial crisis and systemic distress by empowering regulators to mandate higher capital requirements and to establish a new regulatory regime for large financial firms, by developing regulatory and market structures for financial derivatives and by creating systemic risk assessment and monitoring. Dodd-Frank created a Financial Services Oversight Council (FSOC) that identifies and monitors systematic risk in the financial sector. The FSOC recommends appropriate leverage, liquidity, capital, and risk management rules to the Federal Reserve. The FSOC can practically take control of and liquidate troubled financial services firms if their failure would pose significant threat to the nation's financial stability. Ineffective functioning of financial institutions can be detrimental to the real economy, as evidenced in the recent financial crisis when many U.S. and European banks went bankrupt, had to be rescued by government, or were taken over by other financial institutions.

(c) Types of Financial Institutions

There are many types of financial services firms including commercial banks, investment banks, insurance firms, pension plans, mutual funds and sovereign wealth funds that are vital to the financial markets. The more common types of financial institutions are described in this chapter. In view of the range and diversity within financial institutions, this chapter focuses on three major types of entities/activities: banks and savings institutions, mortgage banking activities, and investment companies.

(i) Banks and Savings Institutions

Banks and savings institutions (including thrifts) continue in their traditional role as financial intermediaries. They provide a link between entities that have capital and entities that need capital while also providing an efficient means for payment and transfer of funds between these entities. Banks also provide a wide range of services to their customers, including cash management and fiduciary services, accepting demand and time deposits, making loans to individuals and organizations, and providing other financial services of documentary collections, international banking, trade financing.

Financial modernization and financial reform legislation (Dodd-Frank Act of 2010) continues to change the way banks and savings institutions conduct business. Banks and savings institutions have developed sophisticated products to meet customer needs and technological advances to support such complex and specialized transactions. Continued financial reform may change the types and nature of permissible banking activities and affiliations.

(ii) Mortgage Banking Activities

Mortgage banking activities include the origination, sale, and servicing of mortgage loans. Mortgage loan origination activities are performed by entities such as mortgage banks, mortgage brokers, credit unions, and commercial banks and savings institutions. Mortgages are purchased by government-sponsored entities, sponsors of mortgage-backed security (MBS) programs, and private companies such as insurance companies, other mortgage banking entities, and pension funds. These financial institutions typically provide the long-term loans to businesses and individuals.

(iii) Investment Companies

Investment companies pool shareholders' funds to provide the shareholders with professional investment management. Typically, an investment company sells its capital shares to the public, invests the proceeds to achieve its investment objectives, and distributes to its shareholders the net income and net gains realized on the sale of its investments. The types of investment companies include management investment companies, unit investment trusts, collective trust funds, investment partnerships, certain separate accounts of insurance companies, and offshore funds. Investment companies have grown significantly in recent years, primarily due to growth in mutual funds.

(iv) Credit Unions

Credit unions are member-owned, not-for-profit cooperative financial institutions, organized around a defined membership. The members pool their savings, borrow funds, and obtain other related financial services. A credit union relies on volunteers (owners and users) who represent the members. Its primary objective is to provide services to its members rather than to generate earnings for its owners. More recently, many credit unions have made arrangements to share branch offices with other credit unions and depository institutions to reduce operating costs. Traditionally, credit unions have owned and managed by several members to provide financial services to its members and now have evolved to thousands of members with multi-billion dollars in assets.

(v) Investment Banks

Investment banks or merchant banks deal with the financing requirements of corporations and institutions. They may be organized as corporations or partnerships. Investment banks are financial institutions that assist corporations and governments in raising capital by underwriting and acting as the agent in the issuance of securities. An investment bank also assists companies involved in mergers and acquisitions and derivatives, and provides ancillary services, such as market making and the trading of derivatives, fixed income instruments, foreign exchange, commodity, and equity securities.

(vi) Insurance Companies

The primary purpose of insurance is the spreading of risks. The two major types of insurance are life, and property and casualty. The primary purpose of life insurance is to provide financial assistance at the time of death. It typically has a long period of coverage. Property and casualty insurance companies provide policies to individuals (personal lines) and to business enterprises (commercial lines). Examples of personal lines include homeowner's and individual automobile policies. Examples of commercial lines include general liability and workers' compensation. Banks, mutual funds, and health maintenance organizations are aggressively trying to expand into products traditionally sold by insurance companies. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the insurance industry benefited from the strong stock and bond markets; however, recent slow premium growth and the increased competition and economic meltdown continued to pressure insurers to reduce costs and improve profitability. Many companies in the insurance sector in particular have been adversely affected by the 2007–2009 financial crisis. Insurance companies that were involved in activities traditionally associated with investment banks, and are designated as savings and loan holding companies (SLHCs) and typically offer leverage and risk-based financial products (security-based swaps) have been deeply impacted by the recent crisis.

Implementation of provisions of Dodd-Frank will have significant effects on insurance companies by impacting their business transactions. The newly established Federal Insurance Office (FIO) is intended to play an important role in overseeing and coordinating insurance activities between the international insurance market and the U.S. insurance market. Nonetheless, the FIO will not be in charge of state regulation of insurance companies. The Dodd-Frank Act directed the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to establish rules and standards for broker-dealers and investment advisors will have a substantial impact on insurance companies. The FIO will oversee all aspects of the insurance industry, including systemic risk, capital standards, consumer protection, and international coordination of insurance regulation.

(vii) Finance Companies

Finance companies are non-banking lenders that do not receive deposits but provide lending and financing services to consumers (consumer financing) and to business enterprises (commercial financing). The more common types of consumer financing include mortgage loans, retail sales contracts, auto loans, debt consolidation loans and insurance service. The more common types of commercial financing include factoring, revolving loans, installment, term and floor plan loans, portfolio purchase agreements, and lease financing. Captive finance entities represent manufacturers, retailers, wholesalers, and other business enterprises that provide financing to encourage customers to buy their products and services. Many captive finance companies also finance third-party products. In the pre-financial crisis era, many mortgage finance companies and diversified finance companies increased their presence by increasing the number of loans made to higher-risk niches at higher yields.

(viii) Securities Brokers and Dealers

Securities brokers and dealers serve in various roles within the securities industry. Brokers, acting in an agency capacity, buy and sell securities, commodities, and related financial instruments for their customers and charge a commission. Dealers or traders, acting in a principal capacity, buy and sell for their own account and trade with customers and other dealers. Broker-dealers perform a wide range of both types of activities, such as assisting with private placements, underwriting public securities, developing new products, facilitating international investment activity, serving as a depository for customers' securities, extending credit, and providing research and advisory services.

(ix) Real Estate Investment Trusts

The new class of real estate investment trusts (REITs), formed since 1991, are basically self-contained real estate companies. They are designed to align the interests of active management and passive investors, generate cash flow growth, and create long-term value. Traditionally, REITs relied on mortgage debt to finance their development and acquisition activities. Recently many REITs have taken advantage of their large market capitalization and strong balance sheets to raise cash by issuing debt on an unsecured basis.

30.2 Banks and Savings Institutions

(a) Primary Risks of Banks and Savings Institutions

General business and economic risk factors exist for many industries; however, increased competition and consolidation among banks and savings institutions has resulted in the industry's aggressive pursuit of profitable activities. Techniques for managing assets and liabilities and financial risks have been enhanced in order to maximize income levels. Technological advances have accommodated increasingly complex transactions, such as the sale of securities backed by cash flows from other financial assets. Regulatory policy has radically changed the business environment for banks, savings, and other financial institutions. Additionally, there are other risk factors common to most banks and savings institutions, based on their business activities. The Dodd-Frank Act establishes stricter disclosure requirements and restricts banks' risk-taking appetite by encouraging them to redesign their business lines and services. The other primary risk factors are described next.

(i) Interest Rate Risk

Interest rate risk is the risk that adverse movements in interest rates may result in loss of profits since banks and savings institutions routinely earn on assets at one rate and pay on liabilities at another rate. Techniques used to minimize interest rate risk are a part of asset/liability management.

(ii) Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk is the risk that an institution may be unable to meet its obligations as they become due. An institution may acquire funds short term and lend funds long term to obtain favorable interest rate spreads, thus creating liquidity risk if depositors or creditors demand repayment. The primary function of banks in transforming short-term deposits into long-term loans makes them vulnerable to liquidity risk. Effective liquidity risk management is essential to banks to ensure their ability to meet cash flow obligations. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has released several publications designed to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations to promote a more resilient global banking sector. The BIS (2010, 2011) has established guidance on managing liquidity risk that provides details on:

- the importance of establishing a liquidity risk tolerance;

- the maintenance of an adequate level of liquidity, including through a cushion of liquid assets;

- the necessity of allocating liquidity costs, benefits and risks to all significant business activities;

- the identification and measurement of the full range of liquidity risks, including contingent liquidity risks;

- the design and use of severe stress test scenarios;

- the need for a robust and operational contingency funding plan;

- the management of intraday liquidity risk and collateral; and

- public disclosure in promoting market discipline.

(iii) Asset-Quality Risk

Asset-quality risk is the risk that the loss of expected cash flows due to, for example, loan defaults and inadequate collateral will result in significant losses. Examples include credit losses from loans and declines in the economic value of mortgage servicing rights, resulting from prepayments of principal during periods of falling interest rates.

(iv) Fiduciary Risk

Fiduciary risk is the risk of loss arising from failure to properly process transactions or handle the custody, management, or both, of financial-related assets on behalf of third parties. Examples include administering trusts, managing mutual funds, and servicing the collateral behind asset-backed securities.

(v) Processing Risk

Processing risk is the risk that transactions will not be processed accurately or timely, due to large volumes, short periods of time, unauthorized access of computerized records, or the demands placed on both computerized and manual systems. Examples include electronic funds transfers, loan servicing, and check processing.

(vi) Operating Risk

Operating risk is the risk that losses can occur from internal failures and external events aside from financial risk. Operating risk is the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems, or from adverse effects of external events. This risk imposes a new capital charge to cover losses associated with operational risk.

(vii) Market Risk

Market risk is a risk that associated with earning volatility that caused by adverse price movements in the bank's principal trading positions. Market risk can be measured in terms of value at risk (VAR).

(b) Regulation and Supervision of Banks and Savings Institutions

The legal system that governed the financial services industry in the United States was created in response to the stock market crash of 1929 and the resulting Great Depression. Thousands of banks went out of business, and, in response, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933. Glass-Steagall prohibited commingling the businesses of commercial and investment banking. Its intent was to restrict banks from engaging in business activities that allegedly contributed to and accelerated the stock market crash. In the view of legislators, the way to do this was to confine banks to certain strictly defined activities.

In 1945, Congress enacted the McCarran-Ferguson Act as comprehensive legislation governing the insurance industry. McCarran-Ferguson effectively delegated the responsibility for regulating the business of insurance to the states. Since then, the states have maintained autonomy in their regulatory role with relatively minor, but increasing, exceptions. With the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 and amendments in 1970, Congress limited affiliations between bank and nonbank businesses.

Section 20 of the Glass-Steagall Act took on a life of its own. It limited banks' ability to own subsidiaries principally engaged in securities underwriting. Over time, that section evolved from being considered a prohibition against any securities underwriting to permitting banks to do so through a subsidiary, as long as underwriting revenues did not exceed 25 percent of total revenues of that subsidiary—thus allowing them to meet the not principally engaged test. Over the years, the effective relaxation of those restrictions enabled numerous acquisitions of securities firms by U.S. bank holding companies and by foreign banks.

These barriers also eroded over time through a combination of changes in customer demands and market activities, the increasing use of more sophisticated financial management techniques, advances in technology, regulatory interpretations, and legal decisions. Product innovation played a role, as the industry learned how to rapidly bundle and unbundle risk, creating new securitization products and accessing the capital markets in ways that had not been contemplated under the then-existing regulatory framework.

As banks assumed a larger role in insurance sales, brokerage, and securities underwriting activities, products began to converge in the marketplace, and the perceived benefits from the convergence of these and related activities instilled a new urgency in the effort to modernize and clarify the regulatory framework governing financial services companies.

The GLB Act amended the Bank Holding Company Act to allow a bank holding company or foreign bank that qualifies as a financial holding company to engage in a broad range of activities that are defined by the Act to be financial in nature or incidental to a financial activity, or that the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed), in consultation with the secretary of the Treasury, determines to be financial in nature or incidental to a financial activity. The GLB Act also allows a financial holding company to seek Board approval to engage in any activity that the Fed determines both to be complementary to a financial activity and not to pose a substantial risk to the safety and soundness of depository institutions or the financial system generally. Bank holding companies that do not qualify as financial holding companies are limited to engaging in those nonbanking activities that were permissible for bank holding companies before the GLB Act was enacted.

On July 21, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank), which is considered the most sweeping financial reform since the Great Depression. The Act is named after Senate Banking Committee chairman Christopher Dodd (D-CT) and House Financial Services Committee chairman Barney Frank (D-MA), and its provisions pertain to banks, hedge funds, credit rating agencies, and the derivatives market. Dodd-Frank is about 2,300 pages long, and more than 200 regulations that will arise from the Act have not yet been written. Dodd-Frank authorizes the establishment of an oversight council to monitor systemic risk of financial institutions and the creation of a consumer protection bureau within the Federal Reserve. Dodd-Frank requires the development of over 240 new rules by the SEC, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), and the Federal Reserve to implement its provisions over a five-year period. Dodd-Frank will impact many aspects of the financial services industry, including:

- Foreign banking organizations and foreign nonbank financial companies

- SEC examination and enforcement

- Systemic risk/prudential supervision

- Banks/bank holding companies

- Credit rating agencies

- Non-U.S. asset managers

- Derivatives

- Consumer and mortgage banking

- Alternatives (hedge funds/private equity)

- Large asset managers

- Brokers/dealers

- Insurance companies

Some provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 are summarized next.

- Dodd-Frank broadens the supervisory and oversight role of the Fed to include all entities that own an insured depository institution and other large and nonbank financial services firms that could threaten the nation's financial system.

- It establishes a new Financial Services Oversight Council to indentify and address existing and emerging systematic risks threatening the health of financial services firms.

- It develops new processes to liquidate failed financial services firms.

- It establishes an independent Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to oversee consumer and investor financial regulations and their enforcement.

- Dodd-Frank creates rules to regulate over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives.

- It coordinates and harmonizes the supervision, setting, and regulatory authorities of the SEC and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

- The Act mandates registration of advisers of private funds and disclosures of certain information of those funds.

- It empowers shareholders with a say on pay of nonbonding votes on executive compensation.

- The Act increases accountability and transparency for credit rating agencies.

- It creates a Federal Insurance Office within the Treasury Department.

- It restricts and limits some activities of financial firms, including limiting bank proprietary investing and trading in hedge funds and private equity funds as well as limiting bank swaps activities.

- The Act provides cooperation and consistency with international financial and banking standards.

- It makes permanent the exemption from its Section 404(b) requirement for nonaccelerated filers (those with less than $75 million in market capitalization).

- It requires auditors of all broker-dealers to register with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and gives the PCAOB rulemaking power to require a program of inspection for those auditors.

- It empowers the Financial Stability Oversight Council to monitor domestic and international financial regulatory proposals and developments in order to strengthen the integrity, efficiency, competitiveness and stability of the U.S. financial markets.

- It makes it easier for the SEC to prosecute aiders and abettors of those who commit securities fraud under the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 by lowering the legal standard from knowing to knowing or reckless.

- Dodd-Frank directs the SEC to issue rules requiring companies to disclose in the proxy statement why they have separated, or combined, the positions of chairman and chief executive officer.

In August 2010, the Basel Committee issued its guidance entitled Microfinance Activities and the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. This supervisory guidance highlights the application of the Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision (BCP) to microfinance activities in order to improve practices on regulating and supervising microfinance activities. The guidance is intended to assist global banking organizations to develop a coherent and comprehensive approach to microfinance supervision that addresses:

- Adequate and specialized knowledge of supervisors to effectively identify and assess risks that are specific to microfinance and microlending

- Proper and effective allocation of supervisory resources to microfinance activities

- Establishment of a regulatory and supervisory framework that is cost effective and efficient.

(c) Regulatory Background

Banks and savings institutions have special privileges and protections granted by government. These incentives, such as credit through the Federal Reserve System and federal insurance of deposits, have not been similarly extended to commercial enterprises. Accordingly, the benefits and responsibilities associated with their public role as financial intermediaries have brought banks and savings institutions under significant governmental oversight. For example, to stabilize the financial system during the financial crisis caused by subprime mortgage in late 2007 and 2008, several bailouts were implemented by the governments in the United States, the United Kingdom, and some western European countries. In the United States, after the government brokered sale of investment banks Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, Treasury secretary Paulson and the chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben S. Bernanke proposed a $700 billion bailout for the stabilization of the financial institutions in September 2008.

As a result of the financial repercussions of the Great Depression, the government took certain measures to maintain the stability of the country's financial system. Several new regulatory and supervisory agencies were created to promote economic stability, particularly in the banking industry, and to strengthen the regulatory and supervisory agencies that were in existence at the time. Among the agencies created were the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the SEC, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB), and the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC). The agencies that were strengthened included the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Fed. These entities were responsible for designing and establishing policies and procedures for the regulation and supervision of national and state banks, foreign banks doing business in the United States, and other depository institutions. This regulatory and supervisory structure, created during the 1930s, was in place for almost 60 years. In 1989, Congress enacted the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA), which changed the regulatory and supervisory structure of thrift institutions. The FIRREA eliminated the FHLBB and the FSLIC. In their place, it created the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) as the primary regulator of the thrift industry and the Savings Association Insurance Fund (SAIF) as the thrift institutions' insurer to be administered by the FDIC.

Even though several of the aforementioned federal agencies have overlapping regulatory and supervisory responsibilities over depository institutions, in general terms, the OCC has primary responsibility for national banks; the Fed has primary responsibility over state banks that are members of the Fed, all financial holding companies and bank holding companies and their nonbank subsidiaries, and most U.S. operations of foreign banks; the FDIC has primary responsibility for all state-insured banks that are not members of the Fed (nonmember banks); and the OTS has primary responsibility for thrift institutions. Exhibit 30.1 lists these regulatory responsibilities.

Exhibit 30.1 Supervisor and Regulator

(i) Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

The OCC charters, regulates, and supervises all national banks. It also supervises the federal branches and agencies of foreign banks. Headquartered in Washington, DC, the OCC has six district offices plus an office in London to supervise the international activities of national banks.

The OCC was established in 1863 as a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The OCC is headed by the Comptroller, who is appointed by the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate, for a five-year term. The Comptroller also serves as a director of the FDIC and a director of the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation.

The OCC's nationwide staff of examiners conducts on-site reviews of national banks and provides sustained supervision of bank operations. The agency issues rules, legal interpretations, and corporate decisions concerning banking, bank investments, bank community development activities, and other aspects of bank operations.

National bank examiners supervise domestic and international activities of national banks and perform corporate analyses. Examiners analyze a bank's loan and investment portfolios, funds management, capital, earnings, liquidity, sensitivity to market risk, and compliance with consumer banking laws, including the Community Reinvestment Act. They review the bank's internal controls, internal and external audit, and compliance with law. They also evaluate bank management's ability to identify and control risk.

In regulating national banks, the OCC has the power to:

- Examine the banks.

- Approve or deny applications for new charters, branches, capital, or other changes in corporate or banking structure.

- Take supervisory actions against banks that do not comply with laws and regulations or that otherwise engage in unsound banking practices. The agency can remove officers and directors, negotiate agreements to change banking practices, and issue cease-and-desist orders as well as civil money penalties.

- Issue rules and regulations governing bank investments, lending, and other practices.

(ii) Federal Reserve Board

The Fed was created by Congress in 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act. The primary role of the Fed as the nation's central bank is to establish and conduct monetary policy as well as to regulate and supervise a wide range of financial activities. The structure of the Fed includes a board of governors, 12 Federal Reserve banks, and the member banks. The board of governors consists of seven members appointed by the president, subject to Senate confirmation. National banks must be members of the Fed. State banks are not required to, but may elect to, become members. Member banks and other depository institutions are required to keep reserves with the Fed, and member banks must subscribe to the capital stock of the reserve bank in the district to which they belong.

Since all national banks are supervised by the OCC, the Fed primarily regulates and supervises member state banks, including administering the registration and reporting requirements of the 1934 Act.

The regulatory and supervisory functions and other services provided by the Fed include:

- Examining the Federal Reserve banks, state member banks, bank holding companies and their nonbank subsidiaries, and state licensed U.S. branches of foreign banks

- Requiring reports of member and other banks

- Setting the discount rate

- Providing credit facilities to members and other depository institutions for liquidity and other purposes

- Monitoring compliance with the money-laundering provisions contained in the Bank Secrecy Act

- Regulating transactions between banking affiliates

- Approving or denying applications by state banks to become members and to branch or merge with nonmember banks

- Approving or denying applications to become bank holding companies and for bank holding companies to acquire bank or nonbank subsidiaries

- Approving or denying applications by foreign banks to establish representative offices, branches, agencies, or bank subsidiaries in the United States

- Supplying currency when needed

- Regulating the establishment of foreign operations of national and state member banks and the operations of foreign banks doing business in the United States

- Enforcing legislation and issuing rules and regulations dealing with consumer protection

- Operating the nation's payment system

The Fed recently undertook several initiatives to mitigate the negative impacts of the financial crisis. These include:

- Extending credit facilities to financial institutions and thus improved market liquidity

- Lowering interest rates to eventually a zero-interest-rate policy by the end of 2008

- Taking several quantitative measures to reduce long-term-interest rates and purchase treasury bonds and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS

- Increasing deposit insurance limits and guaranteeing bank debt

- Ordering the 19 largest banks holding companies to conduct compensation stress tests to ensure that they had sufficient capital to with stand financial difficulties and be able to raise needed capital

(iii) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

The FDIC was created under the Banking Act of 1933. The main reason for its creation was to insure bank deposits in order to maintain economic stability in the event of bank failures. FIRREA restructured the FDIC during 1989 to carry out broadened functions by insuring thrift institutions as well as banks. The FDIC now insures all depository institutions except credit unions.

The FDIC is an independent agency of the U.S. government, managed by a five-member board of directors, consisting of the Comptroller of the Currency, the director of the OTS, and three other members, including a chairman, appointed by the president, subject to Senate confirmation.

The FDIC insures deposits under two separate funds: the Bank Insurance Fund (BIF) and the SAIF. From its BIF, the FDIC insures national and state banks that are members of the Fed. These institutions are required to be insured. Also insured from this fund are state nonmember banks and a limited number of insured branches of foreign banks. (After 1991, foreign bank branches could no longer apply for FDIC insurance.)

From its SAIF, the FDIC insures all federal savings and loan associations and federal savings banks. These institutions are required to be insured. State thrift institutions are also insured from this fund.

Currently, each account, subject to certain FDIC rules, in an insured depository institution is insured to a maximum of $250,000. Other responsibilities of the FDIC include:

- Supervising the liquidation of insolvent insured depository institutions

- Providing financial support and additional measures to prevent insured depository institution failures

- Supervising state nonmember insured banks by conducting bank examinations; regulating bank mergers, consolidations, and establishment of branches; and establishing other regulatory controls

- Administering the registration and reporting requirements of the 1934 Act as applied to state nonmember banks

(iv) Office of Thrift Supervision

In 1989, FIRREA created the OTS under the Department of the Treasury. The OTS regulates federal and state thrift institutions and thrift holding companies. As a principal rule maker, examiner, and enforcement agency, OTS exercises primary regulatory authority to grant federal thrift institution charters, approve branching applications, and allow mutual-to-thrift charter conversions. OTS is headed by a presidentially appointed director. The 12 district Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) continue to be the primary source of credit for thrift institutions.

(d) Regulatory Environment

The early 1980s were marked by the removal of interest rate ceilings, the applications of reserve requirements to all depository institutions, expanded thrift powers, and related deregulatory actions. However, the failures of a large number of thrift institutions and commercial banks caused legislators in 1989 and 1991 to increase regulatory oversight. Both FIRREA and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (FDICIA) were directed toward protection of federal deposit insurance funds through early detection of an intervention in problem institutions with an emphasis on capital adequacy. FIRREA also established the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), which took over the conservatorship and liquidation of a large number of failed thrift institutions due to the bankruptcy of the FSLIC. The RTC completed its mission in 1996 at a net cost of approximately $150 billion to the federal government.

In addition to safety and soundness considerations, current banking regulations recognize economic issues, such as the desire for banks and savings institutions to compete successfully with other, less regulated financial services providers and to address social issues, such as community reinvestment, nondiscrimination, and fair treatment in consumer credit, including residential lending. Costs and benefits of regulations are weighed as the approach to regulation of the industry is redefined.

Many provisions of Dodd-Frank are considered to be positive and useful in protecting consumers and investors, including the establishment of a consumer protection bureau and a systemic risk regulator and provisions requiring derivatives to be put on clearinghouses/exchanges. The new Consumer Financial Products Commission (CFPC) will make rules for most retail products offered by banks, such as certificates of deposit and consumer loans. The Dodd-Frank Act requires managers of hedge funds (but not the funds themselves) with more than $150 million in assets to register with the SEC. Some provisions are subject to study and further regulatory actions by regulators, including the so-called Volcker rule to be implemented. Dodd-Frank fails to address the misconception of too-big-to-fail financial institutions, the main cause of the financial crisis—Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the housing agencies and the excessive use of market-based short-term funding by financial services firms.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is intended to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations to promote a more resilient banking sector with proper ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress and to improve risk management, governance, transparency, and disclosures. The Basel Committee examines the market failures caused by the recent financial crisis and establishes measures to strengthen bank-level and micro-prudential regulation to address the stability of the global financial system.

(e) Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act Section 112

Regulations implementing Section 36 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act (FDI Act), as added by Section 112 of FDICIA, became effective July 2, 1993. These regulations imposed additional audit, reporting, and attestation responsibilities on management, directors (especially the audit committee), internal auditors, and independent accountants of banks and savings institutions with $500 million or more in total assets. The reporting requirements were effective for fiscal years ending on or after December 31, 1993. Congress amended the law in 1996 to eliminate attestation reports concerning compliance with certain banking laws; however, management is still required to report on compliance with such laws.

(i) The Regulation and Guidelines

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 is aimed at minimizing the probability of future financial crises and systemic distress by empowering regulators to mandate higher capital requirements and establish a new regulatory regime for large financial firms. The Act is intended to provide more cost-effective and efficient regulatory guidelines for financial service firms and other impacted organizations. These regulatory guidelines are presented in Appendix A to the Act. The guidelines often leave discretion to an institution or its board, while simultaneously providing guidance that, if followed, would provide a safe harbor from examiner criticism.

(ii) Basic Requirements

Each FDIC-insured depository institution with assets in excess of $500 million at the beginning of its fiscal year (covered institutions) is subject to requirements concerning its annual report, corporate governance, and audit committee.

Annual Report

Covered institutions must file an annual report, within 90 days of their fiscal year-end, with the FDIC and other appropriate state or federal bank regulators. The annual report must include:

- A statement of management's responsibilities for:

- Preparing the annual financial statements

- Establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting.

- Complying with particular laws designated by the FDIC as affecting the safety and soundness of insured depositories.

- Assessment by management of:

- The effectiveness of the institution's internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting as of the end of the fiscal year.

- The institution's compliance, during the fiscal year, with the designated safety and soundness laws. Only two kinds of safety and soundness laws must be addressed in the compliance report: (a) federal statutes and regulations concerning transactions with insiders and (b) federal and state statutes and regulations restricting the payment of dividends.

In Financial Institution Letter (FIL) No. 86-94, the FDIC indicated that financial reporting, at a minimum, includes financial statements prepared under GAAP and the schedules equivalent to the basic financial statements that are included in the institution's appropriate regulatory report (e.g., Schedules RC, RI, and RI-A in the Call Report).

On February 6, 1996, the Board of the FDIC amended the procedures that IPAs follow in testing compliance to streamline the procedures and to reduce regulatory burden. Financial services firms must also comply with Sections 302, 906, and 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) to include executive certifications of both financial statements and internal control over financial reporting in their annual reports files with regulators and submitted to shareholders.

Corporate Governance

The globalization of capital markets and financial institutions demands convergence in regulatory reforms and corporate governance measures and practices. Corporate governance measures are state and federal statutes, judicial deliberations, listing standards, and best practices. In the United States, SOX and financial reform legislation signed into law in July 2010 the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act have established new regulatory reforms for financial institutions. The U.K. corporate governance reforms are specified in the 2003 Combined Code on Corporate Governance.

In October 2010, the Basel Committee issued its Principles for Enhancing Corporate Governance to promote effective corporate governance of financial institutions and banking organizations worldwide. These corporate governance principles address:

- The role of the board

- The qualifications and composition of the board

- The importance of an independent risk management function, including a chief risk officer or equivalent

- The importance of monitoring risks on an ongoing firm-wide and individual entity basis

- The board's oversight of the compensation systems

- The board's and senior management's understanding of the bank's operational structure and risks

The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) hosted an Accountancy Summit on October 12, 2010. Participants from more than 50 countries collectively supported the next points relevant to convergence in global corporate governance (IFAC, 2010):

The accountancy profession has a key role to play in strengthening corporate governance and facilitating the integration of governance and sustainability into the strategy, operations, and reporting of an organization.

Boards should be focused on the long-term sustainability of their businesses. As such, corporate governance reform must include strengthening board oversight of management, positioning risk management as a key board responsibility, and encouraging remuneration practices that balance risk and long-term (social, environmental, and economic) performance criteria.

Governance is more than having the right structures, regulation, and principles in place—it is about ensuring that the right behaviors and processes are in place.

Governance mechanisms need to be strengthened at banks and other companies to ensure better oversight of risk management and executive compensation.

More dialogue is needed between policy makers, the accounting profession, and other financial industries to consider how we can work together effectively on a global level.

Audit Committee

Covered institutions must establish an independent audit committee composed of directors who are independent of management. The entire board of directors annually is required to adopt a resolution documenting its determination that the audit committee has met all FDIC-imposed requirements.

The audit committee of any large financial institutions (i.e., total assets of more than $3 billion, measured as of the beginning of each fiscal year) must include members with banking or related financial management expertise, have access to its own outside counsel, and not include any large customers of the institution. If a large institution is a subsidiary of a holding company and relies on the audit committee of the holding company to comply with this rule, the holding company audit committee must not include any members who are large customers of the subsidiary institution. Appendix A to Part 363 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act provides guidelines in determining whether the audit committee meets these criteria.

The audit committee is required to review with management and the IPA the basis for the reports required by the FDIC's regulation. The FDIC suggests, but does not mandate, additional audit committee duties, including overseeing internal audit, selecting the IPA, and reviewing significant accounting policies.

Each subject institution must provide its independent accountant with copies of the institution's most recent reports of condition and examination; any supervisory memorandum of understanding or written agreement with any federal or state regulatory agency; and a report of any action initiated or taken by federal or state banking regulators.

Recent global financial crises and related economic meltdown underscore the importance of board committees, particularly the audit committee in overseeing managerial function of troubled banks and other financial institutions. Audit committees in the post-SOX world are required to protect investor interests by assuming more effective oversight responsibilities in the areas of internal controls, financial reporting, risk assessment, audit activities, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. In the post-SOX period, the audit committee selects the bank's external auditor and reviews the company's annual audited financial statements and internal control over financial reporting.

Lawmakers (SOX), regulators (SEC rules), and listing standards of national stock exchanges (New York Stock Exchange, Nasdaq, American Stock Exchange) generally require public committees to have an audit committee, which must be composed of independent directors with no personal, financial, or family ties to management. Rezaee (2007) states that:

- Audit committee members must be independent.

- Audit committee members to select and oversee the issuer's independent account.

- There must be a procedural process for handling complaints regarding the issuer's accounting practice.

- The audit committee is authorized to engage advisors.

Audit committee oversight responsibilities can be grouped into eight categories:

(iii) Holding Company Exception

In some instances, FDIC regulation requirements may be satisfied by a bank's or savings association's parent holding company. The requirement for audited financial statements always may be satisfied by providing audited financial statements of the consolidated holding company. The requirements for other reports, as well as for an independent audit committee, may be satisfied by the holding company if:

- The holding company's services and functions are comparable to those required of the depository institution.

- The depository institution has total assets as of the beginning of the fiscal year either of less than $5 billion or equal to or greater than $5 billion and a Capital adequacy, Asset quality, Management administration, Earnings, and Liquidity (CAMELS) composite rating of 1 or 2. Section 314(a) of the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 amended Section 36(i) of the FDI Act to expand the holding company exception to be equal to or greater than $5 billion. The requirement that the institution must have a CAMELS composite rating of 1 or 2 remained unchanged.

The appropriate federal banking agency may revoke the exception for any institution with total assets in excess of $9 billion for any period of time during which the appropriate federal banking agency determines that the institution's exception would create a significant risk to the affected deposit insurance fund.

(iv) Availability of Reports

All of management's reports are made publicly available. The independent accountant's report on the financial statements and attestation report on financial reporting controls is also made publicly available. SOX requires public reporting on:

- The audit committee review of both financial statements and internal control over financial reporting

- Management certifications of accuracy and completeness of financial statements and the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting

- External auditor report on fair presentation of financial statements and the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting

- Other financial reports released by management (management Discussion &Analysis, MD&A, earnings guidance).

(f) Capital Adequacy Guidelines

Capital is one of the primary tools used by regulators to monitor the financial health of insured banks and savings institutions. Statutorily mandated supervisory intervention is focused primarily on an institution's capital levels relative to regulatory standards. The federal banking agencies detail these requirements in their respective regulations under capital adequacy guidelines. The capital adequacy requirements are implemented through quarterly regulatory financial reporting (Call Reports and Thrift Financial Reports (TFRs)).

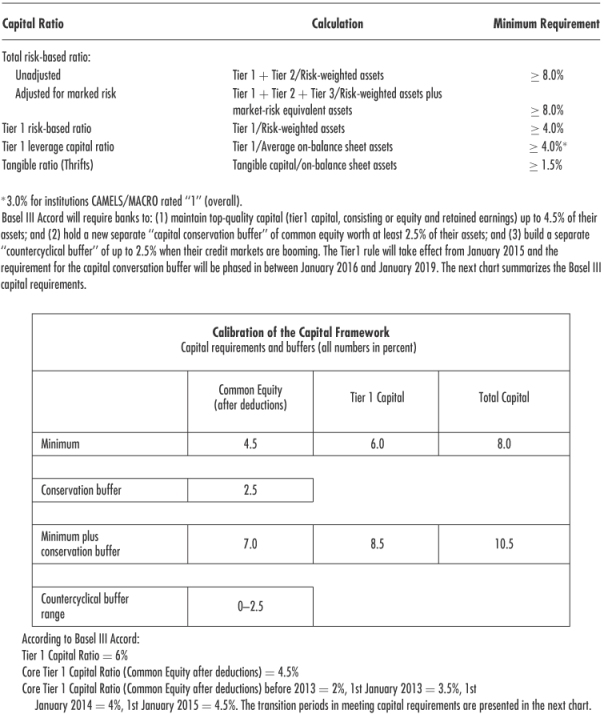

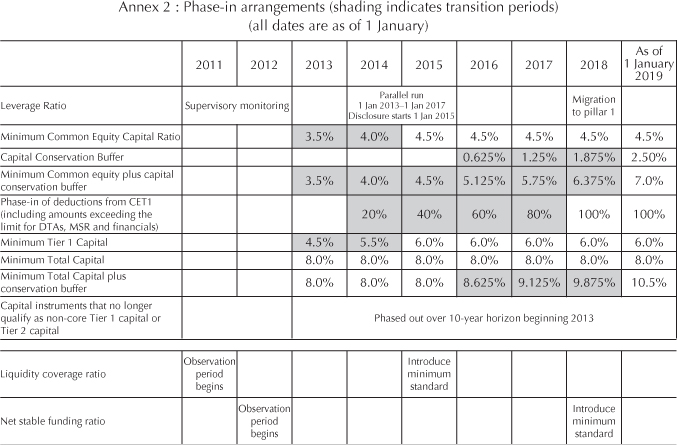

On September 12, 2010, global bank regulators agreed to require banks to significantly increase their amount of top-quality capital in an attempt to prevent further international financial crisis. The Basel III a global regulatory standard on bank capital liquidity, will require banks to maintain top-quality capital totaling 7 percent of their risk-bearing assets compared to the currently required 2 percent. Effective compliance with Basel III rules, which become effective in January 2019, would require banks to raise substantial new capital over the next several years. The primary objective of Basel III rules is to strengthen global capital standards to ensure sustainable financial stability and growth for banks worldwide. The rules are intended to encourage banks to engage in appropriate risk strategies to ensure their financial health and their ability to withstand financial shocks without government bailout supports. Specifically, Basel III will require banks to: (1) maintain top-quality capital (Tier 1 capital, consisting or equity and retained earnings) up to 4.5 percent of their assets; (2) hold a new separate capital conservation buffer of common equity worth at least 2.5 percent of their assets; and (3) build a separate countercyclical buffer of up to 2.5 percent when their credit markets are booming. The Tier 1 rule will take effect from January 2015, and the requirement for the capital conversation buffer will be phased in between January 2016 and January 2019.

(i) Risk-Based and Leverage Ratios

Capital adequacy is measured mainly through two risk-based capital ratios and a leverage ratio, with thrifts subject to an additional tangible capital ratio.

(ii) Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 Components

Regulatory capital is composed of three components: core capital or Tier 1, supplementary capital or Tier 2, and for those institutions meeting market risk capital requirements, Tier 3. Tier 1 capital includes elements such as common stock, surplus, retained earnings, minority interest in consolidated subsidiaries and qualifying preferred stock, adjustments for foreign exchange translation, and unrealized losses on equity securities available for sale with readily determinable market values. Tier 2 capital includes, with certain limitations, elements such as general loan loss reserves, certain forms of preferred stock, long-term preferred stock, qualifying intermediate-term preferred stock and term subordinated debt, perpetual debt, and other hybrid debt/equity instruments. Tier 3 capital consists of short-term subordinated debt that meets certain conditions and may be used only by institutions subject to market-risk capital requirements to the extent that Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital elements do not provide adequate Tier 1 and total risk-based capital ratio levels.

Specifically, Tier 3 capital:

- Must have an original maturity of at least two years

- Must be unsecured and fully paid up

- Must be subject to a lock-in clause that prevents the issuer from repaying the debt even at maturity if the issuer's capital ratio is, or with repayment would become, less than the minimum 8 percent risk-based capital ratio

- Must not be redeemable before maturity without the prior approval of the institution's supervisor

- Must not contain or be covered by any covenants, terms, or restrictions that may be inconsistent with safe and sound banking practices.

Tier 2 capital elements individually and together are variously restricted in proportion to Tier 1 capital, which is intended to be the dominant capital component.

Certain deductions are made to determine regulatory capital, including goodwill and other disallowed intangibles, excess portions of qualifying intangibles and deferred tax assets, investments in unconsolidated subsidiaries, and reciprocal holdings of other bank's capital instruments. Certain adjustments made to equity under GAAP for unrealized gains and losses on debt and equity securities available for sale under Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Statement No. 115, mainly unrealized gains, are excluded from Tier 1 and total capital. Portions of qualifying, subordinated debt, and limited-life preferred stock exceeding 50 percent of a bank's Tier 1 capital are also deducted. Any regulatory capital deduction is also made to average total assets for ratio computation purposes. The new market-risk capital guidelines discussed in section vi also contained further capital constraints, by stating that the sum of Tier 2 and Tier 3 capital allocated for market risk may not exceed 250 percent of Tier 1 capital allocated for market risk. Thrift's tangible capital is generally defined as Tier 1 capital less intangibles.

(iii) Risk-Weighted Assets

The capital ratios are calculated using the applicable regulatory capital component in the numerator and either risk-weighted assets or total adjusted on-balance-sheet assets as the denominator, as appropriate. Risk-weighted assets are ascertained pursuant to the regulatory guidelines that allocate gross average assets among four categories of risk weights (0, 20, 50, and 100 percent). The allocations are based mainly on type of asset, type of obligor, and nature of collateral, if any. Gross assets include on-balance-sheet assets, credit equivalents of certain off-balance-sheet exposures, and credit equivalents of certain assets sold with recourse, limited recourse, or that are treated as financings for regulatory reporting purposes.

Credit equivalents of off-balance-sheet exposures are determined by the nature of the exposure. For example, direct credit substitutes (e.g., standby letters of credit) are credit converted at 100 percent of the face amount. Other off-balance-sheet activities are subject to the current exposure method, which is composed of the positive mark-to-market value (if any) and an estimate of the potential increase in credit exposure over the remaining life of the contract. These add-ons are estimated by applying defined credit conversion factors, differentiated by type of instrument and remaining maturity, to the contract's notional value. The nature and extent of recourse impacts the calculation of credit equivalents amounts of assets sold or securitized. In December 2001, the banking agencies issued a final rule amending the agencies' regulatory capital standards to align more closely the risk-based capital treatment of recourse obligations and direct credit substitutes. The rule also varies the capital requirements for position in securitized transactions and certain other exposures according to their relative credit risk and requires capital commensurate with the risks associated with residual interests.

(iv) Capital Calculations and Minimum Requirements

The capital ratios, calculations, and minimum requirements are presented in Exhibit 30.2.

Exhibit 30.2 Capital Ratio Calculations and Minimum Requirements

Source: Basel III Accord: The new Basel III framework. www.basel-iii-accord.com

In summary, Basel III rules set forth tougher capital requirements by providing more restrictive capital definitions, requiring higher risk-weighted assets, capital buffers, and higher minimum capital ratios. These Basel III standards are expected to affect profitability and transformation of the business models of many banks as well as other bank activities in regard to stress testing, counterparty risk, and capital management infrastructure. Implementation of provisions of Basel III is expected to demand more standardized risk-adjusted capital requirements that will enable investors to better analyze and compare risk-adjusted performance

In the United State, the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP) has increased capital levels by requiring many U.S. banks to increase their capital levels (the current Tier 1 common median for U.S. banks is 9 percent) and providing an adequate transition period of eight years to generate further capital buffers through earnings generation.

(v) Interest Rate Risk and Capital Adequacy

OTS capital rules require that certain savings associations with excessive interest rate risk exposure (as defined) must deduct 50 percent of the estimated decline in its net portfolio value resulting from a 200 basis point change in market interest rates in excess of 2 percent of the estimated economic value of portfolio assets. In August 1995, the banking agencies amended their minimum capital requirements explicitly to include consideration of interest rate risk but did not establish a means for quantifying that risk to a specific amount of additional capital. During 1996, the federal bank regulatory agencies approved a policy statement on sound practices for managing interest rate risk in commercial banks but did not include a standardized framework for measuring interest rate risk. The agencies elected not to pursue a standardized measure and explicit capital charge for interest rate risk due to concerns about the burden, accuracy, and complexity of a standardized measure and recognition that industry techniques for measuring interest rate risk are continuing to evolve.

(vi) Capital Allocated for Market Risk

In September 1996, the federal bank regulatory agencies—the OCC, FDIC, and Fed—amended their respective risk-based capital standards to address market risk. Specifically, an institution subject to the market risk capital requirement must adjust its risk-based capital ratio to take into account the general market risk of all positions located in its trading account and foreign exchange and commodity positions, wherever located and for the specific risk of debt and equity positions located in its trading account. Market risk capital requirements generally apply to any bank or bank holding company whose trading activities equal 10 percent or more of its total assets or whose trading activity equals $1 billion or more. In addition, on a case-by-case basis, an agency may require an institution that does not meet the applicability criteria to comply with the market risk guidelines, if the agency deems it necessary for safety and soundness purposes, or may exclude an institution that meets the applicability criteria.

No later than January 1, 1998, institutions with significant market risk were required to:

- Maintain regulatory capital on a daily basis at an overall minimum of 8 percent ratio of total qualifying capital to risk-weighted assets, adjusted for market risk

- Include a supplemental market-risk capital charge in their risk-based capital calculations and quarterly regulatory reports

- Maintain appropriate internal measurement, reporting, and risk management systems to generate and monitor the basis for the VAR and the associated capital charge

The institution's risk-based capital ratio adjusted for market risk is its risk-based capital ratio for purposes of prompt corrective action and other statutory and regulatory purposes.

Institutions are permitted to use different assumptions and modeling techniques reflecting distinct business strategies and approaches to risk management. The agencies do not specify VAR modeling parameters for internal risk management purposes; however, they do specify minimum qualitative requirements for internal risk management processes as well as certain quantitative requirements for the parameters and assumptions for internal models used to measure market risk exposure for regulatory capital purposes.

There are several models of risk assessment and management, including most widely used models of VAR developed through statistical ideas and probability theories. VAR utilizes a group of related models that share a mathematical framework by measuring the boundaries of risk in a portfolio over short durations. The portfolio can consist of equities, bonds, derivatives, or other financial instruments, and risks can be measured in terms of diversification, leverage, and volatility as a proxy for market risk. VAR takes into consideration both individual risks and firm-wide risks.

Financial institutions use VAR to quantify their risk positions for both internal and external purposes. The extensive use of derivatives by many firms in the late 1990s and the early 2000s encouraged regulators such as the SEC and the Basel Committee to establish rules and guidance to require public quantitative disclosures of market risks in their financial statements. VAR then became the primary model of assessing and managing risks. The Basel Committee even allowed banks to rely on their own internal VAR measures in determining their capital requirements.

Backtesting

Institutions must perform backtests of their VAR measures as calculated for internal risk management purposes. The backtests must compare daily VAR measures calibrated to a one-day movement in rates and prices and a 99 percent (one-tailed) confidence level against the institution's actual daily net trading profit or loss (trading outcome) for each of the preceding 250 business days. The backtests must be performed once each quarter. An institution's obligation to backtest for regulatory capital purposes does not arise until the institution has been subject to the final rule for 250 business days (approximately one year) and, thus, has accumulated the requisite number of observations to be used in backtesting. Institutions that are found not to have appropriate models and backtesting programs or if backtesting results reflect insufficient accuracy likely will be required to incorporate more conservative calculation factors that would result in a higher capital charge for market risk. It has been argued that too much reliance on VAR and its widespread use in determining capital requirement do not consider the important risk of potential financial meltdown.

Basel rules require that bank stress tests consist of:

- The stressed VAR (SVAR), which is computed on a 10-day 99 percent confidence level and three times the 10-day 99 percent stressed VAR will should be maintained

- Model inputs that are calibrated to historical data from a continuous 12-month period of significant financial stress

- Maintenance, on a daily basis, of the capital requirements determined based on the higher of its latest stress VAR number and an average of SVAR numbers calculated over the preceding 60 business days multiplied by the multiplication factor

Risk factors considered in pricing models should also be included in VAR calculations.

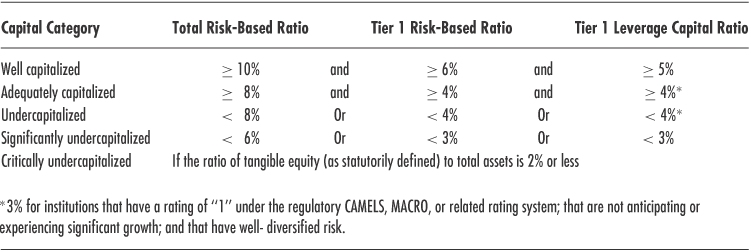

(g) Prompt Corrective Action

The federal banking agencies are statutorily mandated to assign each FDIC-insured depository institution to one of five capital categories, quantitatively defined by the risk-based and leverage capital ratios.

Institutions falling into the last three categories are subject to a variety of prompt corrective actions, such as limitations on dividends, prohibitions on acquisitions and branching, restrictions on asset growth, and removal of officers and directors. Irrespective of the ratios reported, the agencies may downgrade an institution's capital category based on adverse examination findings.

The regulatory capital ratio ranges defining the prompt corrective action capital categories are summarized in Exhibit 30.3.

Exhibit 30.3 Regulatory Capital Categories

Federally insured banks and savings institutions are required to have periodic full-scope, on-site examinations by the appropriate agency. In certain cases, an examination by a state regulatory agency is accepted. Full-scope and other examinations are intended primarily to provide early identification of problems at insured institutions rather than as a basis for expressing an opinion on the fair presentation of the institution's financial statements. The Dodd-Frank Act has substantially increased the enforcement oversight function of the SEC and the Federal Reserve Board and their examination programs to regulate the financial services industry effectively.

(i) Scope

The scope of an examination is generally unique to each institution based on risk factors assessed by the examiner. Some examinations are targeted to a specific area of operations, such as real estate lending or trust operations. Separate compliance examination programs also exist to address institutions' compliance with laws and regulations in areas such as consumer protection, insider transactions, and reporting under the Bank Secrecy Act.

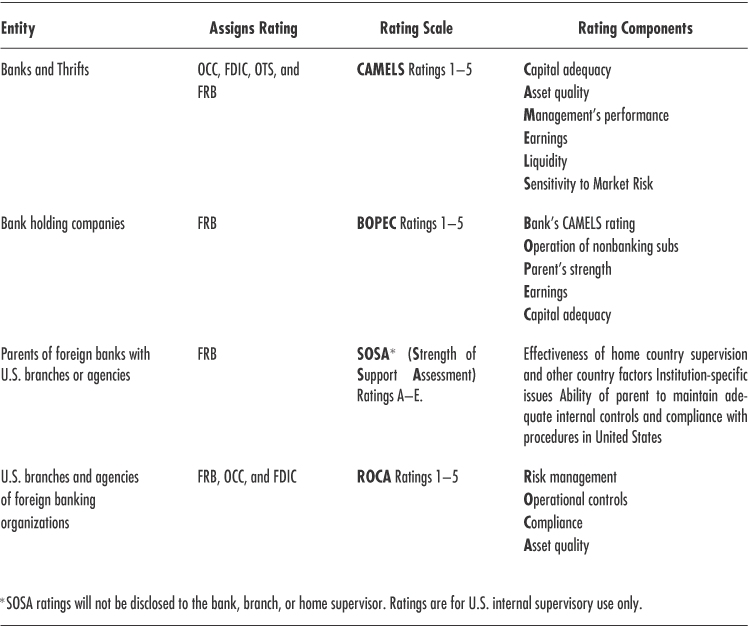

(ii) Regulatory Rating Systems

Regulators use regulatory rating systems to assign ratings to banks, thrifts, holding companies, parents of foreign banks, and U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banking organizations. The rating scales vary, although each is based on a 5-point system, with 1 (or A) being the highest rating. The rating systems are presented in Exhibit 30.4. Additionally, in November 1995, the Fed issued Supervision and Regulation Letters (SR) No. 95-51, Rating the Adequacy of Risk Management Processes and Internal Controls at State Member Banks and Bank Holding Companies. It states that Federal Reserve System examiners, beginning in 1996, are instructed to assign a formal supervisory rating to the adequacy of an institution's risk management processes, including its internal controls.

Exhibit 30.4 Regulatory Rating Systems

The Dodd-Frank Act addresses activities, practices and structure of the nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (NRSROs), better known as credit rating agencies. Specifically, provisions of Dodd-Frank pertaining to NRSROs include:

- Mandating internal control requirements for NRSROs

- Improvements in governance practices of NRSROs

- Addressing potential conflicts of interest of NRSROs

- Imposing new liability exposure on NRSROs

- Requiring new methodology and procedures to be used in credit ratings process

- Requiring more transparent disclosures on credit ratings process

- Increasing SEC oversight of NRSROs

(iii) Risk-Focused Examinations

Over the last two decades, the banking agencies have been developing and implementing a risk-focused examination/supervisory program that focuses on the business activities that pose the greatest risks to the institutions and assesses an organization's management systems to identify, measure, monitor, and control its risks. Bank examiners should learn from factors that caused the global financial crisis, pay attention to all types of bank risks, and recognize the importance of risk-focused examination and supervision in preventing further financial crises. It is evidenced the extend, nature and complexity of international financial transactions, in the years preceding the start of financial crisis in 2007, bank supervisors and examiners failed to develop adequate and effective risk-focused techniques to properly deal with the complex situations.

(h) Enforcement Actions

Regulatory enforcement is carried out through a variety of informal and formal mechanisms. Informal enforcement measures are consensual between a bank and its regulator but are not legally enforceable. Formal measures carry the force of law and are issued subject to certain legal procedures, requirements, and penalties. Examples of formal enforcement measures include ordering an institution to cease and desist from certain practices of violations, removing an officer, prohibiting an officer from participating in the affairs of the institution or the industry, assessing civil money penalties, and terminating insurance of an institution's deposits. As previously discussed, other mandatory and discretionary actions may be taken by regulators under prompt corrective action provisions of the FDI Act. The Dodd-Frank Act has provided more resources and mechanisms for U.S. regulators such as the SEC and the Federal Reserve to more effectively enforce irregularities and violations of securities laws that threaten the health and financial stability of the nation. The Dodd-Frank Act directs regulators to issue more than 240 rules in implementing its provisions such as the Volcker rule, which would ban proprietary trading by those banks that benefit from Fed borrowing privileges and deposit insurance as well as whistle-blowing rules in providing incentives and protections for whistleblowers to report violations of securities laws and other irregularities to regulators.

(i) Disclosure of Capital Matters

Beginning in 1996, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Audit Guide for Banks and Savings Institutions required that GAAP financial statements of banks and savings associations include footnote disclosures of regulatory capital adequacy/prompt corrective action categories. There are five minimum disclosures:

If, as of the most recent balance sheet date presented, the institution is (1) not in compliance with capital adequacy requirements, (2) considered less than adequately capitalized under the prompt corrective action provisions, or (3) both, the possible material effects of such conditions and events on amounts and disclosures in the financial statements should be disclosed. Additional disclosures may be required where there is substantial doubt about the institution's ability to continue as a going concern.

These disclosures should be presented for all significant subsidiaries of a holding company. Bank holding companies should also present the disclosures as they apply to the holding company, except for the prompt corrective disclosure required by item 4.