So far, we have looked at what we might call the frame to a performance and the principles that underlie its creation. In this chapter, we will get down to looking at the physical components of a performance, the way that such things as body language, and the effort that goes into any kind of movement, can create the impression of a thinking, autonomous character, a character that seems to have a life of its own.

We will look at what human beings actually do when they interact with other humans and how they use their bodies in different situations, both mundane and extreme, not because we think that you will always be animating human characters, you probably won’t be, but because human behavior is behind most of what you will do. As we’ve noted in previous chapters, you might be animating rabbits but, unless they are to be seen as real animals, they are acting as stand-ins for people and will need to display the kind of traits we see around us in society.

As “Ren and Stimpy” creator, John Kricfalusi says, “Human acting as I understand it doesn’t mean acting just like humans, it means expressing unique and specific things in response to what is specifically happening and what the characters should be feeling about what is actually happening, such as humans naturally do. It can still be cartoony or exaggerated, and is completely compatible with cartoony physics.”

The nature of the physical body is something else we need to look at too, since the way the character is constructed will determine how he or she moves. Above all, we will look at how, by getting the character right in physical terms, we can capture that most elusive of things, thought.

Body Language

When I’m out on the hill near my home taking the dog for a walk, I often encounter a lady, with whom I have a nodding acquaintance, coming the other way with her dogs. I never see her in any other context, such as in the street, so I only know her from these brief morning encounters but I can recognize her when she is merely a tiny figure in the distance, and it’s all down to body language, or, if you prefer, nonverbal communication.

When we communicate face to face with another person, we are never just using verbal language and we are communicating even when we aren’t speaking. There is no real agreement on how much meaning we take from the nonverbal component of communication, some people putting it as high as 90%, others as low as 50%, but there is no disagreement on the fact that it is a very important part of how we do communicate. When we meet someone for the first time, we don’t have to wait for them to open their mouth before we have formed an opinion of them and equally they of us. We may change our initial impression as we get to know them, but the way we get to know them is also based not just on what they say but also on all the nonverbal signals they give out all the time. It isn’t possible to stop giving out nonverbal signals, though people who understand what’s going on can often fake the signals to a degree, and actors, and by extension, animators, can use this knowledge to create a powerful performance.

As animators and directors, we need to be attuned to the possibilities of nonverbal communication because nobody gets by without it; in fact, we are made uneasy when we can’t detect body language that ought to be there, and our characters will only really come alive when we make them give off the right signals. The right stance will mean the difference between a person and a sign and an understanding of nonverbal signals will help create a real personality.

The Uncanny Valley

The Uncanny Valley is a term coined by professor of robotics Masahiro Mori and is the hypothesis that the more human a robot’s (and by extension a CG or puppet character’s) appearance becomes, the more empathetic and positive will be the response of an observer, up to a point where that response turns to one of revulsion. As the simulation gets progressively further from the robotic and closer to the human, the empathetic response will start to return. This “dip” in response can be seen plotted on the graph and gives rise to the ‘uncanny valley term.

Fig. 6.1 The more human a character’s appearance becomes, viewers will respond with more empathy, up to a point where that response turns to one of revulsion.

The reasons behind this aversion are not fully understood and still subject to research and speculation, including the idea that no matter how good the simulated person becomes we will still be able to tell, subconsciously, that they are somehow “other” but it is very interesting from a performance point of view. Though it was once thought that CG films would naturally have to progress to absolute realism, it can now be seen that we can stylize our characters as much as we like without losing empathy for them.

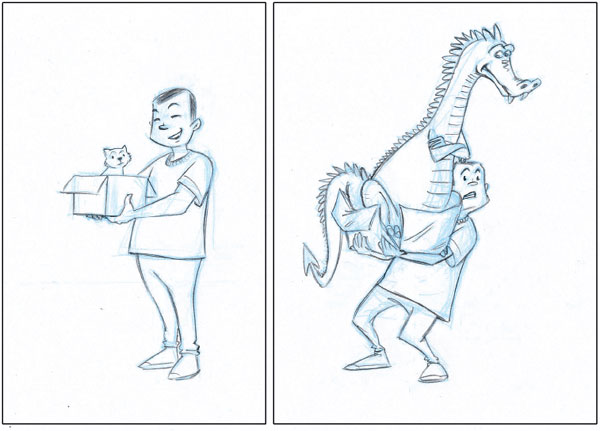

Fig. 6.2 It doesn’t take much to turn a personality free sign into something with a feeling of character. Just add a touch of body language, a tilt of the hips perhaps, or a change in the shoulders.

As Brad Bird, director of The Iron Giant and The Incredibles says, “One of my problems with full animation is, often times, people do beautiful movement, but it’s not specific movement. Old people move the same as young people, women move the same as men, and fat people move the same as thin people… and people don’t move the same. Everybody moves differently…”

What Brad Bird is looking for is the study of movement that is specific to character and not just conventionally well animated and, in The Incredibles, he set out to make sure that each character could be recognized by their movement as much as by their design. His aim was to create within his team an agreement on who the character was and how he or she moved so that even if they all had the same body shape they could be distinguished by their movement. An aim that is very similar to the way that the Disney animators had to work with the dwarfs in Snow White, and the way to do this is to make sure that you have taken note of and studied body language.

The lady with the dogs walks in a very particular way that I recognize from a long way off. She has a very determined stride, a way of leaning forward as she goes, with arms held by her sides that seems very purposeful and no-nonsense, as if she knows exactly what she’s about and she’s completely in control. Then again, since this kind of stance could also be interpreted as rather closed off and uptight, I could assume that she was a nervous and rather fearful type who felt she had to keep moving so that no one could talk to her and possibly upset her.

So immediately we can see the problems inherent in talking about body language; if it is a language, it is one that is often easy to misunderstand and, unlike verbal language, doesn’t actually have a vocabulary that everyone agrees on. In fact, many gestures that say one thing in one culture can mean another in another culture, so it isn’t as simple as saying this gesture indicates that feeling although many of the nonverbal signals we use are the same across all cultures.

As we mentioned in Chapter 5, there are certain signals generally accepted as being understood in the same way across cultures and therefore held to be part of our genetic makeup. These are happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, surprise, and anger, and Charles Darwin, in his book, The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), was the first to claim they were universal. His theory has been challenged over the years but has, since the 1960s, been acknowledged to be correct.

Even though these six traits are universal, body language isn’t an exact science, though increasing investigation, using brain-imaging technologies, is giving greater insight into what goes on in the interaction between brain and body and how thoughts and feelings translate into movement, both conscious and unconscious.

It’s easy to misread signals, especially if context isn’t taken into account. Many lists of body signals say that crossing the arms across the chest denotes defensiveness, the person closing him or herself off from an idea, for example, or resisting an argument. It could be, though, that they were merely trying to keep warm. Shifting from foot to foot can signal shiftiness or untrustworthiness, though it could equally mean the person needs to pee!

Sideways headshaking means disagreement or disbelief in Western cultures but a similar movement in India or by people of Indian descent means agreement or that the person is listening closely.

There are cultural differences that come into play when working with artistic conventions too. While making The Miracle Maker, I spent a lot of time with my Russian colleagues who were doing the model animation, discussing the work they had done, and going over what I wanted for up-coming scenes. Mostly, ideas about acting were common to both sides though I tended to have a more naturalistic idea of how I wanted to deal with the story of Jesus than they did and occasionally something would crop up that took me by surprise.

For one particular scene, where Jesus is taken before the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, we had a cast of characters arguing their case in a noisy and dramatic assembly. Pilate angrily orders them to be quiet; “or I will charge you all with disturbing the peace of Rome!” And he makes an imperious hand gesture, with arm outstretched and fingers splayed, palm pointing at the floor as he does so. So imperious and over the top that it seemed like a caricature to me and, indeed, the origins of the gesture were in various examples of painting and statuary, some of which I’d seen around Moscow.

Ironically, for the country that gave us Stanislavsky, the father of naturalistic or Method acting, they were much more likely to use artistic conventions than real body language to depict important moments of the drama. I could understand this to a certain extent; since the Revolution, they had not had general access to debates over religion or the number of different ways the story of Christ had been done in the West, from Jesus Christ, Superstar to Dennis Potter’s play, Son of Man, so they had had to fall back on iconography from painting and sculpture that was still available in their museums. It was hard to change the animators’ minds on this point, since they considered it a legitimate use of a specific gesture that looked both dramatic and imposing and natural to such an authority figure. It was only when I told them that, in English, “peace” sounded just the same as “piece” and it would look like Pilate was charging the crowd with disturbing a specific piece of Rome (lurking just out of the bottom of frame) that they gave in and decided they would do it again without the gesture.

(I have to say that, despite the difficulties inherent in a coproduction across so many miles and with such differences of culture the work that the Russian animators produced is absolutely terrific in its ability to reproduce complex emotions and engage the audience.)

One size never fits all when it comes to body language; there are things we can say about the kind of movement that results from certain bodily conditions, but context is all when it comes to interpreting the signals sent out by another person. As many of us will have found out to our cost, body language can be faked and people who have something to sell us try to do this all the time. This is not to say that salespeople, for example, are necessarily trying to deceive us, but the simple fact is that they have to try to give out a sense of reassuring honesty and solidity even when they are feeling below par or have worries of their own. Then there are those who are out to deceive, and they really need to project an image of stability. They are the ones who will have studied how to hold themselves and where to look while lying in your face.

So, if we are studying or observing people in order to reference real ideas about movement in our animation, it is a good idea not to rely on a single example of nonverbal communication but to look at all the signals a person is giving out and find in the combination a better clue to meaning.

Other factors will also come into play when we attempt to either analyze or recreate body language; we’ve mentioned ethnicity and context, such as temperature, but even more obvious are the differences between men and women, the young and the old. For example, young people will generally be more supple and energetic than older people and, depending on how young they are, probably less inhibited in their movements. Women, on the whole, tend to be more inhibited than men; though as social mores change (in Western societies, mainly), this is becoming less true.

Leaving aside for a moment those people like politicians, salesmen, and con-artists (and actors), whose professions demand they try to alter their body language, we can say that nonverbal communication is not a matter of choice but something we do without thinking about it. Indeed, it is something that we do even when we don’t need to do it, because it is hard-wired into us. We’ve all seen people in the street on their mobile phones gesticulating away despite the fact that the person on the other end can’t see them and, as the instructor on my speed awareness course said, “if you breathe in when driving through a narrow gap, you’re going too fast”. Like the man in Figure 6.3, we have to move our bodies when communicating, presumably as a legacy of the thousands of years when we had no language and had to communicate the way animals do.

Fig. 6.3 It’s a cliché that Mediterranean types have to move and gesticulate when talking but we all do it to a greater or lesser extent.

You’ve probably seen a child wanting to tell her mother something as the mother is chatting to someone else. Unable to get a word in and told to keep quiet, the desperate need to communicate comes out as a twisty, hopping dance that has the child building up to a volcanic eruption of sound. Conversely, think of the soldier being harangued by the sergeant and having to respond while standing rigidly to attention. Quite apart from the fact he is on the receiving end of a telling off, he is unable to use any body language to explain himself, assert himself, or create a submissive posture that his hindbrain might think was a way to get out from under the torrent of abuse. Very uncomfortable.

Despite the fact that “the eyes are the windows to the soul” and our eyes are drawn to faces when people speak, we are actually taking in an enormous amount of information from a person’s stance, from hand positions, and the way we tilt our heads; we communicate with our whole body. The lady with the dog is so far away from me when I first see her coming that her face is a tiny smudge but the attitude and silhouette of her body is what I recognize.

Paul Mendoza, animator on several Pixar movies, including ‘UP ’, ‘WALL-E’, and Ratatouille when talking about his animation at the Bradford Animation Festival in 2010, talked about how important the eyes were to a performance but also, more surprisingly, of how much the movement of the shoulders brought to it. Our hips and shoulders are the pivot points in the body and these are the places where we show the weight of a character, with women generally carrying more weight lower down in the hips and men carrying more in the shoulders and we can immediately imagine a curvaceous woman leading with her hips or a brawny man moving with rolling shoulder movements. We tend to forget though how much our emotions can show up in the way we hold our shoulders, both men and women. Get into a tense situation and you will often find that your shoulders are heading up towards your ears and when the problem passes the release of tension allows them to slump back down. (This is how, quite literally, a person can be a “pain in the neck.” Someone who annoys you, without the possibility of a release of anger will cause you to tense your shoulder muscles and give you a stiff neck.)

An aggressive character will lead with his head down and chin out but when the verbal aggression turns into action he will bring his head right down into his shoulders and his arms will come up. A person disappointed by some action or slight will slump, their shoulders drooping, and all these actions can be seen in miniature, almost in rehearsal, before a character has to do something that will arouse the same emotions in someone else. Thus, it is possible to animate a character with their back to the camera and still have the audience understand exactly what he or she is feeling.

Character Interaction

Animated films can often feature single characters going about their business until assaulted by giant letters of the alphabet or stranded alone on a desert island, and we still utilize body language to allow the audience to understand what they are feeling. In fact, lacking another person to talk to, body language is often all we have to go on in assessing the character’s mental state. More usually, we are dealing with the interaction of characters and we have to provide body language that is a dialogue of action and reaction, of nonverbal responses, one to the other.

One obvious aspect of this communication is proximity, the distance characters are from each other. This, like other things, can depend on different social interaction in different societies; extended personal space can be expected in one society wherein another people will be quite happy to be quite close to each other. Naturally, this also changes depending on the sex of the persons interacting. However, it is interpreted, someone entering the personal space of another without permission will be seen as aggressive or crass. Lovers and friends, of course, have each other’s permission to remain in close proximity and that easy closeness indicates the state of a relationship without the use of words. In the same way, if one character is always trying to stand next to another and the second character is always moving away, we can see what is going on without the need for additional dialogue.

So, proximity is one factor that shows the relationship between characters, but there are several other factors that can observed during interaction, including what is known as mirroring.

When people are in sympathy with one another or, consciously or unconsciously, want to give that impression, their body language begins to become synchronized, they adopt similar postures indicating a rapport has been achieved. (Speech patterns, speeds, and tones also become synchronous.) When this happens, the speaker will feel the other person is empathetic and likes them; they will feel a kind of affirmation. If this doesn’t happen, communication can become very uncomfortable; unconsciously, the speaker will feel a resistance on the part of the other person.

Another important feature that can indicate the relationship between two characters relates to where they actually stand when speaking together. Facing someone directly can be very confrontational, but it can also be a sign of two people who feel a great deal of affection for one another. Someone can be “in your face” or “up close and personal,” and this face-to-face stance is always intense, so, even when people meet like this to shake hands in order to do business, they will very soon get into an arrangement that will allow them to be at an angle to one another. The classic boardroom situation is people facing each other across a large table, but modern business thinking regards this as overly antagonistic and sees sitting or standing at an angle of about 45° as much more comfortable and conducive to cooperation. You can see how this works for yourself when in conversation; if you are coming on too strong or being slightly over enthusiastic, whether it be in an aggressive or an affectionate manner, the person to whom you are talking will tend to edge round to the side so that you are not in looking directly at them.

An understanding of these principles can be applied to any kind of character, not only a human but also something quite abstract. With this in mind, we can show the relationship of a square and a triangle or two germs as well as a boy and a girl.

Eye contact is an interesting question too since reactions to it differ in different societies. In some places, it is thought rude to look an older and more respected person in the eye, in others we have the command, “look at me when I’m talking to you,” All good for interesting misunderstandings.

One thing that seems to generally happen within conversations, in terms of eye contact, is the difference between speaking and listening. A person who is listening to another will usually signal interest by looking at the person who is talking while the speaker will mostly look elsewhere, only looking at the listener occasionally as if checking to see if they are still there. These roles reverse when the speaker changes. Obviously, the listener, unless they are bored or trying to be rude, will want to signal that they are attentive and considerate; looking at the speaker is the simplest way to do so. This is often accompanied by head movements, like nodded agreement, and vocal affirmations or agreement.

The speaker, in contrast, is often remembering the thing she is describing or coming up with an idea or making a joke and when doing that we tend to look away to either the left or right. This seems to have something to do with the way our brains are wired, the left side dealing with memory and facts and the right with creativity, so that we look up and to the right when coming up with ideas and down and to the left when remembering facts.

Learning about listening is a very important part of an actor’s training (see Chapter 2 as it is not enough for an actor to be good at what he does with his own speech and body language; if he doesn’t appear to be being listened to by others, the audience won’t believe in him. The problem of working with a script where you know what is coming can lead to a flow of words and action that is artificial and doesn’t correspond to what would happen in real life where we have, at best, only a vague idea what a person is going to say. We also have to be able to react to what is said and done and that can’t happen without some kind of thought on our part. Actors train to listen to one another to the extent that they sometimes do an exercise where their lines are handed to them just before they are to say them. They still have to learn those lines before they go on stage but the training in listening is what they take with them. Listening is an activity just as speaking is, and in animating characters talking together, we have to consider the nonverbal signals our listening characters are giving out as they listen. A person who is listening to someone else is not just standing there, he is taking in what the speaker is saying and formulating a response, judging what is being said or being amused by it. He may be getting angry about it or being bored, but he will have his own thoughts and his body language will let us know what they are. You may be doing a piece of limited animation where there is no chance to animate the crowd standing in front of the man giving the speech, but the poses you give them need to tell the viewer exactly what they are feeling about the speech or the speaker.

Equally, a character that enters a room but doesn’t have anything to say right away or one who is on the fringes of the action but has no lines isn’t just standing around doing nothing. If the character is listening to the exchanges going on, then she will have her own feelings about what is happening and her body language is going to express those feelings, even if she hasn’t got the chance to act on them.

In a piece of limited animation, where there isn’t chance to do much more than pose her, her body language needs to seem like a reasonable response to what is going on, while being a pose that could reasonably be held.

Disney animator Ollie Johnston always said, “Find the golden pose, and build the scene around that pose.” In the same way that the director should work to understand the single most important point that the audience needs to get out of each scene, in order to understand where the film is going, the “golden pose” is the one that says what you want the animation to say in that scene. Often the pose will come out of the storyboard and, of course, it isn’t the only pose you’ll do for the scene, but the others will work to support that one to create the effect you are aiming for. A really good pose will read well and will show what the character is thinking. Chuck Jones was a master of the pose that was both funny and meaningful at the same time; he never over-animated things or let his animators over-animate things and always made sure that the important poses read well. What made this work so well was that, as well as holding a good pose, he made sure that he didn’t have the character freeze into position but, with judicious use of cushioning and overlapping action, like a tail or ear that caught up just a little latter, he could make a much more subtle effect and keep the character alive.

Johnson also said, “It’s surprising what an effect touching can have on an animated cartoon. You expect it in a live-action picture or in your daily life but to have two pencil drawings touching each other, you wouldn’t think would have much of an impact but it does.” This thought reflects, to me, the need to give the characters a sense of that autonomy we mentioned in the introduction. When the characters touch, they seem to acknowledge each other’s reality, quite apart from the one we give them, and it seems odd that this idea isn’t used more often. Think how seldom we see characters touching in a simple, natural way, and how contact is often restricted to the Prince’s kiss or the bad guy’s punch.

As ever, these notes are only ever intended as the baseline from which to work, and the creation of both comedy and serious drama means moving away from the expected or the cliché to the surprising and the particular. As with any language, many of the words are the same for everybody, but the way each person puts them together, their accent, intonation, pronunciation, and turn of phrase add up to the very particular individual.

So, although many people would like to have a list of readily available mannerisms that could be relied upon to indicate certain moods or feelings, it isn’t possible to set them down with any certainty. It is true that, once upon a time, acting was taught in this way, as a series of gestures that meant something specific. Actors would put the back of their hand to their forehead and swoon backward to indicate a shocked reaction to some revelation or become stooped and wring their hands to indicate servility. We’ve all seen this kind of performance spoofed by actors and comedians or someone playing the part of an amateur performer and the great Bugs Bunny mercilessly parodies this sort of acting, as in What’s Opera Doc?.

The work of Stanislavsky signaled the end for exaggerated staginess, as we discussed in Chapter 2, but this telegraphing of the emotional state of the character is still too often part of the journeyman animator’s repertoire, and many animators would like there to be a simple system of visual clues to emotional states. Sadly, it isn’t as simple as that (what is?), but www.businessballs.com/body-language.htm is a very useful website about body language, although you need to remember the provisos we’ve mentioned here when you look at it.

Effort

Understanding body language and trying to get feeling into a character is important, but the physicality of a performance is vital if the character is going to be believable. Without weight and a sense of the forces acting on and through the character, all the clever posing will go for nothing. Even if the character is light as air, a thing entirely possible in animation, we need to put over some sense of the effort that goes into being that way. A cloud is insubstantial, blown every which way by the wind, but if we intend to give the cloud a personality and make it actually do something in a believable way, it will need to move itself and react to the forces that act upon it.

For all the other characters, the ones that do have weight and solidity, it is even more important to feel the forces at work and make their feet hit the ground, make their muscles strain as they pull themselves up the cliff face, and make them stagger as they carry that cannonball. Or, if they are a fish, or a bird, or a dragon, they need to convincingly move through water or air, pushing against it and being buffeted by it. Without a convincing sense of the reality of the character, all the good design, all the fine drawing or puppet building, and all the brilliant character modeling will be wasted.

When I started teaching character animation, I usually set an exercise to do with weight and I ask my students how we might show that a ball the character has to pick up is heavy.

Simple question, eh? But some of the answers I get are often very convoluted and strange. Suggestions I have had include “show cracks on the ground underneath it”; “make it shiny and metallic”; and “write 10 tons on it.” I elaborate and say that, no, we won’t be using color or words; in fact, we will just draw the heavy ball as a simple circle, but I often still don’t get the answer I’m looking for.

Fig. 6.4 Heavy, heavier, heaviest?

Now these are not stupid people, they have just not been able to see the wood for the trees, as it were. They seem to treat it as almost a trick question. But the answer is very simple. When we take away all other clues and the ball is a pencil circle on a ground plane defined by another line, the only way we can see that it is heavy when another force acts upon it. In this case, our character comes along and tries to pick it up.

That’s not the end of the story though; in trying to define how we show that the ball is heavy when lifted, the answer is not in the amount of sweat that pours off the character’s brow nor the straining noises on the soundtrack, it is in the effort the character expends in trying to lift it. In showing that effort, we use many of the animation principles laid out in the classic Disney studio list, The 12 Principles of Animation, that we noted in the Introduction:

- Squash and Stretch

- Anticipation

- Staging

- Straight Ahead Action and Pose to Pose

- Follow Through and Overlapping Action

- Slow In and Slow Out

- Arcs

- Secondary Action

- Timing

- Exaggeration

- Solid Drawing

- Appeal

We won’t need all of these in order to produce the effect we are looking to achieve but many of them are essential components. Appeal we’ll leave aside, and assume that our character is well designed and full of personality and within Solid Drawing, we’ll subsume the solid constructional values of a stop motion puppet or a computer-animated character. Staging will be useful insofar that we show the action from a vantage point that allows us to see the movement well; in this case, probable a three-quarter view from the front at eye level, but Straight Ahead or Pose to Pose animation is mostly to do with how we want to animate rather than what we are animating. Let’s assume a simple character without floppy clothing, so we don’t need to think too much about Follow Through; clothes aren’t going to show us much in the way of effort anyway.

So our character faces the ball and goes into an anticipation; not, as some students think, an opportunity to do some funny little strong man poses before he starts, but the way in which he leans over the ball, hunkering down to be ready to use his powerful thigh muscles. This anticipation, as we will see, is one of the most useful tools in our animation arsenal when showing effort.

Fig. 6.5 First the anticipation, leaning into the ball and getting purchase. Then he braces himself, pulling backward as his arms stretch. Then, er…

So, he moves in to the ball, the anticipatory movement always coming as a move in the opposite direction to the way in which the main motion is going to go.

Then he starts to straighten up, and we can use squash and stretch here to show how the weight of the ball is affecting his body, with his feet, perhaps squashing down into the ground and his arms stretching and lengthening before the ball has even moved. The ball, we will assume, is a cannonball and not amenable to squash and stretch even in our cartoon universe.

The amount of Exaggeration we use is entirely up to us and depends on the way we have designed our universe. A very cartoony universe will allow for a lot more squash and stretch, a more realistic one will demand less though all will benefit from a certain amount of exaggeration.

As our character stands and the ball leaves the ground, we will be using our skills in timing to create the Slow Out that creates the acceleration from a resting position. The fact that the acceleration is slow and minimal shows how much effort it takes to get the ball moving.

The fact that the body moves up and back before the ball moves means that the movement of the ball could be classed as Secondary Action but secondary action will certainly be present as the body gets to the top of its move and the head comes up after it.

In all these actions, we can see the presence of Arcs because one thing that we really need in order to show the weight of this object is Balance. To keep the ball off the ground, the character will have to balance the weight (which is what he would be doing with his own weight if he were standing still, to avoid falling over, but now the need to be balanced is crucial). Essentially, if we draw a center line through the figure, the weight of the character and the ball must be balanced on either side of that line. Since we assume the weight and solidity of the character from the type of character he is and the way he is built, we look at the way the ball is balanced and make conclusions about the weight of the ball. So, if the ball is held at arms length, we know it isn’t very heavy because the person holding it doesn’t have to lean back to take more of the weight toward the center line. The heavier it is, the more he will lean back, balancing the weight of the ball with the weight of his body, and if it is really heavy then the whole ball will need to rest on the center line with the body acting as a stand on which it rests. The ball will move in an arc as it comes up from its resting position on the ground to its rest in mid air (and naturally there will be a slow in to the rest position as the character resists the momentum he has created).

So, a simple action, but one that relies on a large number of animation principles in order to create the feeling of effort that leads to a good performance of that action.

This may feel very simplistic; after all, what has this got to do with putting over great depths of emotion or a series of great gags that set the audience alight? But there is a reason that this is one of the early animation exercises that are given to students; if you can’t get over to an audience, the effort required in picking up a heavy ball, how will you get over the effort required to do anything? And effort isn’t just what happens when we pick up something heavy, it is not exclusively to do with difficulty or big emotions, it is present in all actions.

Fig. 6.6 The first is not a heavy object; he hardly has to bend backward. The second is so heavy he needs to keep it balanced over his center of gravity.

Bill Tytla, Disney animator on films including Dumbo and Fantasia said, “The first duty of the cartoon is not to picture or duplicate real action or things as they actually happen, but to give a caricature of life and action. The point is that you are not merely swishing a pencil about but you have weight in your forms and do whatever you possibly can with their weight to convey sensation. It is a struggle for me and I am conscious of it all the time.”

Everything is inert until something comes along to get it moving; it’s not a new thought, it is Newton’s First Law of Motion. The ball will stay put until someone comes along to pick it up or a car hits it or natural forces cause it to rust away. We will sit in that chair until we decide to get up and do something, the difference between us and the ball is that we are alive and can move ourselves, either through a conscious decision or through reflex action (when the sharp spring shoots up through the bottom of the chair). Reflex action we’ll consider later but our concern here is with the action that is initiated by our character, and that action is initiated by thought and feeling.

The use of anticipation is one of the main differences between a character that can act of his or her own volition and an inanimate object. If an object moves into an anticipation before the main move, it shows volition and is alive. If it is not alive, it can only be acted on and, if it moves, that movement must be driven by an external force so that it can only accelerate from a stationary position, in the direction of the force that acts upon it.

Before we go on, I need to emphasize here that a character differs from the ball in another way in that he is not actually completely inert when he is sitting in the chair. Actions don’t come from nowhere and a character shouldn’t be a complete blank until the animator gets him going, he needs to be doing something, playing an action, as actors say, even if that is very minimal. The reason is, of course, that we are telling a story and the story has a dynamic, it is going somewhere. So even daydreaming is an action because it is based in personality, he is daydreaming for a reason and even if he’s sitting in the armchair, bored and picking lint from his clothes, he is doing something that is meaningful in terms of the story. It may be that his girlfriend has dumped him and his daydreaming is coming out of anger and frustration. The way he picks the lint off his shirt in this case will be a lot different to the way he would be doing it if he were thinking about her before the dumping. In one case angry little flicks, in the other more languid and dreamy; both displaying a minimum of effort but both driven by internal forces and each of them requiring a different way of using the animation principles above.

If being dumped, he then comes to the conclusion that he isn’t going to take this lying down, he’ll get up and rush off, maybe to give her a piece of his mind or perhaps to try to make up with her. There will be effort involved in getting up in either case, but the way he gets up and the way he walks off will be coming from a different place for the different emotions. If he hasn’t been dumped at all, he might be off to tell her how much he loves her; once again, the emotion is different and the simple act of standing up is changed by that emotion.

Most of the time, people don’t think about their actions as they perform them. In fact, it’s usually a bad idea to do so; try running up stairs and start thinking about running while doing it—a recipe for falling on your face. (The authors accept no responsibility for anyone taking them too literally and actually falling upstairs.) So, in getting up, our character’s movement is controlled by well-developed motor functions, but the nuances of that move are dictated by his emotions.

You can see that, in coming up with an example of a character getting up from an armchair, I couldn’t explain it in the same way I did the character picking up the ball. When the character picks up the ball, it works as a simple starter exercise, since the process is pretty mechanical and we don’t need to know the backstory. On the other hand, immediately we start to think about someone getting up from a chair, we start asking questions about what is going on; what’s the story here? The character’s intention in getting up is now part of the equation and I wouldn’t think of giving this as an exercise unless I also gave the students a bit of storyline to work with. I might say what I wrote above that here was a man dumped by his girlfriend, sitting disconsolate, until he decides that he’s going to try to win her back. Alternatively, the figure in the armchair could be Sherlock Holmes, pondering a problem and then suddenly arriving at a conclusion that springs him out of the chair, or a sad old man whose wife has died, hearing a persistent knock on the front door when he would rather be left alone. All three of these characters will be sitting in different ways and will get up in different ways, each one dependent on the story we are telling, played out through the emotions that are filtered through their separate personalities, and enacted by their various physical types.

There are a huge number of permutations in the way that these different elements come to make up the persons we create. In this instance, the young man could be fat or thin, athletic or weedy, college educated, a nerd, lazy or hard working, a country boy or a city gent, independently wealthy, down on his luck, a bit dim or junior Einstein, etc. etc. And any combination, from any country you care to name. So if he’s clever, an idea may come to him in a flash, but if he’s overweight he won’t be able to respond as swiftly as he might like and there might be a bit of resentment there that leads to a realization that his girl might have had her reasons for dumping him. Some of this might become apparent in the way he sets his shoulders and pulls in his stomach as he goes off to see her.

Interestingly, although the student running through a range of strongman poses before having his character pick up the ball was wrong in thinking this was the kind of thing that made up anticipation, I think he had unconsciously picked up on the need for a story or idea behind the action. What he was doing was creating a reason why the man was going to pick up the ball, some kind of motivation to create an objective for him. He is a strongman and this is what a strongman does. Often students will not be able to leave it at that; just a strongman in the act of picking up a heavy object, they will also want to add a gag at the end to round off the story.

As you can see, we’re storytelling animals, and they are not wrong in doing this, they are responding to the need to situate the action in an explanatory framework, they can see that there has to be a lead in to an action and there is always a follow-through. This is true of the emotional, storytelling aspect; the guy has been dumped, he gets up because he wants to get the girl back, and realizes maybe he needs to lose a little weight and be someone she can admire; and it is true of the way in which we animate the actions he goes through. When we animate, we need to be conscious of the importance of the buildup to an action and the results of that action. This is why anticipation is vital, because no action comes completely out of the blue. Anticipation tells us why the character is taking the action and the thinking behind it, even more so when the action itself is very swift, like throwing a punch. This doesn’t mean that the anticipation itself has to take a long time, but if we animate the punch in the way that reads strongly and go right past the contact point, we need that flash of anticipation to tell us what is in the character’s mind as he begins his move. How the character follows through from the punch is important too. Is there a feeling of triumph, of instant regret that he lost his cool, or has he suddenly realized what he is capable of? Will he dance back, ready for the next round, or freeze as he realizes the guy he punched has friends all around?

It is important to really “feel” what you are animating, to get inside the emotional core of the action, so it is vitally important that you understand the character and the scene and how it fits into the overall structure of the film, series, whatever. There are several ways of going about this; if you are dealing with an established character, you will be able to watch previous series episodes, the director or lead animator may have written a character study or you will go through the idea for the scene with the director. However, when it comes to creating the physical performance, it is not good enough to rely on only a cerebral understanding of the character, we really need to work from the inside out.

There are two good ways of doing this that go hand in hand; acting out the action and thumbnailing the scene.

Fig. 6.7 Like a throw, a punch gains more force from the wind-up or anticipation. Pulling back gives the arm further to go and it can cover the distance fast, putting power into the movement. The anticipation also acts like a spring to “bounce” the movement off. Unless you want to do this in slow motion and enjoy the distortion as fist hits face, it is more powerful not to show the point of contact and have the first travel past the point of impact. That way we feel that the blow has been so powerful we only see the result.

The only way to really understand how to get the body language right is knowing what you do about the character and try to act it out as them. The great Disney animators didn’t shy away from doing this though they realized they weren’t great actors in the stage sense (if they had been, they might well have done that rather than turn to animation), but they found enough in the acting out of a scene to give them a clue to the physical sense of a character. I realize difficulties might arise if the character is a fish or a cloud but the principle applies because, if I can refer you back to the discussion about Shere Khan in Chapter 5, the fish or cloud is really only a human in disguise. By doing even an imitation of the action, no matter how badly, you will start to find something in there that you can use. In particular, you will probably find you are holding yourself in a certain way or that the voice is being produced in a particular part of your body and you will get a clue to the way this fish or this cloud has of holding itself. Then it is on to thumbnailing the action using this knowledge. Take a look at Kaa the python in Disney’s version of The Jungle Book (1967, Wolfgang Reitherman) and see how the animator, the great Milt Kahl, uses the long snake’s body in lieu of hands and shoulders. Shere Khan asks Kaa where Mowgli might be and Kaa replies, “Search me,” pulling up his body to give a shrug and then, realizing he has said the wrong thing, immediately coiling part of himself to cover his mouth as if it was a hand. Then when Shere Khan squeezes Kaa’s body to feel if he’s eaten Mowgli, he twists up like a shy girl who has been tickled.

Fig. 6.8 Kaa, from Disney’s The Jungle Book, is a picture of innocence.

Fig. 6.9 Thumbnail sketches are a way of working through an idea, of trying out a performance before getting into the difficult and time-consuming work of animating. Here Joanna Quinn works out how a character in “Elles” should untie her bundle.

(We’ll look in more depth at this way of preparing for a performance in Chapter 7, Scene Composition.)

Milt Kahl was someone who would then go on to wrestle with the insights he had gained by making thumbnail sketches of as many variations on the action as he could until he found the right one. As Brad Bird remembers:

“He believed that if his animation was better than anyone else’s, it was because he worked harder. Literally each scene is the result of a lot of decisions that were made. That’s why the scenes feel so rich when you watch them. He was always trying to push everything to its ultimate statement. And when you watch a scene, you’re seeing one ultimate statement going on to the next.”

Silence

In 1951, composer John Cage visited Harvard University and was shown their anechoic chamber, a room specially designed to absorb sounds rather than have them reflect as echoes. Such chambers feature external soundproofing and internal walls, ceilings, and floors composed of materials that absorb or scatter sound in such a way that it becomes undetectable by the human ear.

Cage went into the chamber expecting to hear nothing, pure silence, but he later wrote, “I heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation.”

Cage had found sound where he had expected pure silence.

Later, Cage wrote his famous piece, 4’33” (Four minutes, thirty three seconds) (1952) in which the performer or performers are instructed to sit without playing anything for the specified time. Though it is often thought of as four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, such a performance is anything but silent; there will always be the sounds of the concert hall, the sounds filtering in from outside, and, as Cage found in the anechoic chamber, the sounds of the audience’s own bodies. As the Bonzo Dog Doo Da Band noted on the album sleeve for A Doughnut in Grannie’s Greenhouse, “The noises of your body are part of this record.” The work is actually intended to get the listener to engage more fully with the act of listening and to realize that sounds are going on all the time. It also opens up the idea that music is not just the thing that is made by the players of instruments, but can be the whole sphere of our aural experience; music is everywhere. Arguably, this is the auditory version of what Marcel Duchamp was doing when he brought the “Readymade” art object into the art gallery; by putting a urinal on show and calling it Fountain he was breaking down the wall between high art and the rest of the world and saying that art was all around, that art is about what one chooses to be art, and that, in that case, there is nothing that is not art.

So silence does not exist and everything is art. And what has this to do with performance?

Well, I would suggest that silence must be as much a part of a performance as any of the gestures or speeches that make up what we normally understand as performance, that silence is dynamic, that silence is not an absence but a presence.

Without silence, without pauses, there is just the continuous hum of words and action and the danger is that an audience just goes along with it, lulled into a sort of trance, and misses the important stuff you are trying to get over. With the silence, the audience sits up, pays attention, just the way you do when a noise that’s been going on in the background so long you no longer hear it, stops.

To stick with music for a moment, one of my favorite songs is “Doctor Feelgood” by Aretha Franklin, and one of the best, most spine-tingling moments in that song comes at the end when she puts in a perfectly timed pause before the final word. It’s worth listening to the recording to see how that pause brings the song to a staggering conclusion.

Listen to your favorite comedians too, and see how much they owe to their sense of timing; see where the joke falls and reflect that timing is the ability to balance the right words with just the right pause that brings the house down. My wife is my toughest critic and one of her criticisms of my work is that I put too much in and don’t leave enough spaces. I like to flatter myself she’s just like the Emperor in Amadeus, criticizing Mozart for having written “too many notes,” but she is often right (not always, honest), and I have to bear this tendency in mind when I work and strive to achieve the perfect relationship of notes to rests.

Actor Sir Ralph Richardson said, “The most precious things in a speech are pauses. A pause will fill the void, capture attention; it will punctuate, illuminate and build the tension in a speech.”

And we are not just talking about a speech, because when we talk about silence we are also talking about stillness, the pauses we put into our visuals that do the same job of enhancing the performance. The pregnant pause is a staple element of any comedy film but the cartoon takes it almost as far as it can go. Any Roadrunner cartoon will offer a series of wonderful examples of brilliantly timed pauses that create the comedy. Take a look at Zoom at the Top (1962) Chuck Jones and admire the way the timing builds a delightful tension as the Coyote tries to set up a bear trap in the middle of the road. Later, the Roadrunner comes along and the trap fails to spring even when he jumps on it, so the Coyote goes to investigate and, inevitably, the trap shuts on him. Take in the pause before it does so and the brilliant fact that Chuck Jones cuts to a shot of empty desert as it shuts, so we don’t actually see anything. Then the beat before the mangled figure of the Coyote limps into shot. Of course, the pause that always occurs between the Coyote dwindling to nothing as he falls away from camera and the puff of dust as he hits the canyon floor is an example of nothingness to rank with the pause in Doctor Feelgood.

Let’s be clear, though; when we talk about stillness or silence, we aren’t talking about nothing happening—a total lack of sound or a freeze frame. The action may pause while speech goes on or a character may fall silent and still be moving, slowly, and subtly.

But here’s an extreme example of stillness: I was once lucky enough to spend a day looking at films and talking with Terry Gilliam; this was when I was at film school and my friend Phil and I were the only animators there at the time. Terry was not as well known as he is now and, amazingly, we had him all to ourselves. While he seemed to like what he saw of our animation, he felt that the full animation style we were working in was too much work for him and he told us about his favorite of the pieces he had done for Python. The scene, he said, consisted of a dog lying on the pavement with two off-screen voices arguing over whether the dog had moved or was dead. Despite the fact that there was only one, completely immobile, illustration of the dog, he said that lots of different people swore they had seen it move. He chuckled a lot when he told us that story, but it does illustrate a serious point, two points in fact, that sound can make things come alive and that audiences want to get something out of what they see on screen and don’t mind doing some work to find it. A moment of stillness, if handled correctly, will become meaningful depending on the moments surrounding it.

These moments are very powerful for an audience, especially when they come to punctuate the whirl of the action.

Let’s say that at the big reveal moment in the movie a young character asks a pretty important question, like, “If you’re not my father, then who is?” The character who asks the question wants desperately to know the answer, and so too do the audience who have been following him on his quest. They can see this is the moment everything is about to change. They are hanging on every word. At this point, the revelation will mean something to both the older and the younger person, there will be a current running between them and this is where silence is at its most powerful.

The audience will be leaning forward, ready to hear what comes next, focused on the performers and trying to read into the silence. They will be thinking, trying to work things out by looking at every nuance of the movement, each glance of the eyes—and sometimes it will only be a glance that they will get, sometimes only the tension going out of the older character’s shoulders as he comes to a decision.

So how long is a silence, or a beat, or how long should they be? And is a pause the same as a beat? Well, we might say that a silence is probably longer than a pause and a pause is longer than a beat but, as with body language, there is no chart of definitive answers to this. With body language, we can at least point to certain signs that seem to mean the same thing in most contexts, with silences we have nothing to go on but feeling. We have to learn how to judge a pause in the same way we learn how to tell a joke and realize that any example of silence or stillness comes from one thing, the action. What we shouldn’t do is to fetishize the idea of the meaningful pause in the same way that an indulgent actor might try to add gravitas to his performance by pausing for a “significant” amount of time. This is just a way of saying, “Look how clever I am; I’m really emoting here.”

When things stop, they stop for a reason that is completely to do with what is going on in the movie, they pause because the action demands it. It may be a revelation or a question that demands an answer, the shock of a re-appearance or the need to dredge up memories. It might be that a character has just given up in disgust with no more words to say, they might be speechless with rage or so worn out trying to get over the mountain that they slump to the ground, but they will stop for a reason and start again when another reason asserts itself.

Even the Roadrunner cartoon has its beats defined by the necessity of the action, rather than just as a pause to allow for laughter. In To Beep or not to Beep (1963, Chuck Jones), the Coyote is startled by the Roadrunner into leaping up and smashing his head through an overhanging rock. The next shot is a high angle looking down on his head poking out of the overhang, and his expression is the only thing that changes, but in that static moment, he goes through a range of emotions that register pain, disappointment, anger, and the birth of a cunning plan. He makes a transition from defeat to defiance that gets him back on the search for victory and takes the story forward again. So, although we might argue that the Coyote is an entirely predictable character, never changing in his single-minded pursuit of the Roadrunner, the ability to see his thought processes seems to give him an added dimension that makes him more sympathetic and engaging. It is as if we could see how hopelessly trapped he is in this quest and how he knows it too.

If a character is angry, her rant may run up against the simple fact that she has made the object of her anger cry. She has to pause, something in her is touched and she has to rethink, to come up with a new action to change the situation. In the example above, the older man who has been acting as the younger character’s father realizes that the time has come to tell the truth. He may or may not have rehearsed this moment in his mind many times but now he has to deliver the speech he is caught off guard and he pauses, uncertain of how to start. Whatever it is, the reason for the pause is in the action that leads up to it and the end of it comes when something forces speech or the resumption of action, the woman has to try to stem the flow of tears or the child’s false assumption of his real father’s identity forces the previous father figure to speak out.

In the BBC TV adaptation of Dickens’ Great Expectations (2011, Brian Kirk), there is a wonderful example of a pause that is truly significant and informs everything that is to come. Young Pip (Oscar Kennedy) encounters the escaped convict Magwitch (Ray Winston) on the Kent marshes. Magwitch, a hulking brute covered in mud and blood, sends the boy to steal a file from his uncle, the blacksmith, threatening him with all manner of harm if he informs on him. Pip returns with the file and Magwitch starts to work on his fetters, expecting the boy to leave, but Pip pulls out of his pocket a piece of pie he has also taken and offers it to the convict. Magwitch just stares at him. And in that stare, the whole of the story turns and, though we do not know it yet, makes off in a different direction. In that pause, Ray Winston shows what a great actor he is as his thought processes are written on his face; though his expression hardly seems to change, we see his shock at the fact that he has been treated with kindness, though he has not been kind. We see his worldview start to change, the humanity he has lost to a world of crime, and punishment is revealed still to be there, deep within him. All without a word being spoken. Later, when he is recaptured, this moment is all that is needed to explain why he does not tell the soldiers that Pip brought him the file and why he confesses to the theft of the pie so that Pip is not blamed.

It is a wonderful moment and really highlights the greatest advantage of the use of silence and stillness, the ability to reveal the mind of a character. This is where the concept of autonomy comes in again; we can see the thoughts going through the mind of the character but we are not privy to all of them, or we see the process but have to wait to find out what decision has been made. This means the character appears to know more than we do and, because we are human and empathetic, we can credit another being with the power of independent thought and therefore, life.

We might hope to reach the kind of acting that we see in “Great Expectations” in a feature film context, but we can keep it in mind even if we are working on a limited budget or scale. It costs nothing to add in a moment of stillness that transforms the drama but it does require the ability to empathize with how the character is feeling at any given moment and express that on screen in whatever animation technique you are using. This is where the ability to pose a character well is important and the study of body language is essential to make that pose work. The interesting question then is, how do you come out of that pose to suggest that something has changed in the moment of stillness? If, for example, the villain has been brought up short by some revelation, then decides that to give in to this new idea would be weak, and he will go back to his previous intention, he will still need to reset himself. The character is in possession of new information and cannot now act as if he were ignorant of it. His body language will now be a negation of what he knows to be true so perhaps he fights with more ferocity since he is fighting himself as well as the hero, or perhaps he has decided that he is doomed now and it is too late to change his fate so he fights with a grim resignation. However it goes, the silence is made meaningful by what is on either side of it as well as what goes on within it.

As we have noted above, animated films often feature a single character acting out a role that brings him into contact with objects rather than other people. In fact, although we know them as Roadrunner cartoons, the films featuring the fleety fowl should perhaps be better known as Coyote cartoons since we spend most of our time with him as he tries to get yet another one of his Acme purchases working. In these situations, the Roadrunner is often no more than a blur of dust and a cheery “Meep, Meep.”

In these situations, the moment of silence or stillness will be brought about by an internal realization and not by someone else. But in many cases, we are working with more than one character, and this leads us on to the question of how to deal with secondary and background characters.

We have already dealt with the way one character needs to listen to another and the need for every character to be playing some kind of action or intention within Body Language, but here we need to look at the contribution others make to the effect of silence.

Say we were animating the extract from “Great Expectations” referred to above. We have the tableau of Magwitch stock still, brought up short by an unexpected act of kindness, but also Pip holding out the slice of pie and anticipating that the convict will take it from him. Since it is the effect of this action on Magwitch that we are most interested in, we do not want Pip to be doing anything that will divert attention from him, but we have to judge the extent of this pause and how much we can do before we need to bring it to an end. And we need a natural end that will bring us back to the present reality of mud and iron fetters. Pip’s, “Don’t you want it then?”, becomes the simple, prosaic way in which the tension is broken, allowing a hungry Magwitch to come back to himself and grab the pie.

The moment of stillness of one character may be enhanced by the activity of other characters in a scene, creating the opposite of what we usually find when our eye is drawn to activity. This can make for very powerful storytelling, but we have to choreograph the scene carefully in order to focus the viewer’s eye on the thing we want them to see. It is always the case that motion will attract the attention of a viewer, but it is also true that the eye is drawn to areas of contrast and a thing that stands out by virtue of the fact it is different, whether that be a difference of tone, form, color, or motion.

So while a good strong pose is important in all animation, it is particularly important here since it will be the solidity of the pose that registers amid the surrounding action.

The motion against which you have set up the contrast also has a role to play in making sure that we are looking in the right place. What needs to happen is that the action has to become de-individuated, that is, it has to stop looking like individual actions that we want to look at and become something like a moving mass that has no focal point to lead the eye. So repetition is useful, which can be cycles where appropriate, color contrasts are toned down, the individuality of the surrounding characters is de-emphasized and the framing of the shot is designed to lead the eye to the character we want to focus on.

Reflex and Other Physical Reactions

Although we have talked a lot about the concept of characters being seen to think, and the importance of giving them motivation, needs, and wants, not all actions come out of conscious thought or volition; some reactions are built in and bypass the conscious mind. Stick your hand on a pin and you don’t have to think about moving your hand away, before you can understand that you have been hurt, your hand will have moved. It used to be thought that a signal from the hurt would have to travel all the way to the brain in order for it to send back a signal to make the hand move away but we now understand that the signal from the sensory neuron goes no further than the spinal cord. There it crosses the synapse to the motor neuron and comes back to cause a muscle contraction that moves the hand away. The sense of pain comes a moment later because the signal that triggers the sense of pain does have to go all the way to the brain to be processed.

One thing to remember when animating a reflex action is that, although the hurt may be in the hand, for example, it is not only the hand that moves, the reaction spreads out through the body. In particular, when a person is walking and steps on a tack or a sharp stone, if he only responded by lifting the injured leg, he would probably fall flat on his face. Not only is there a need to signal the leg to stop moving down and to move away from the hurt, but also other signals need to tell the rest of the body to rebalance the weight. Even in the case of small pains, there will be a tremor within the rest of the frame, an almost sympathetic action from the other members, so that if the right hand reacts to a heat source and pulls back, the shoulders may come up and the other hand may do a similar action—only later. The initial, reflex action is coming straight from the spine, the other, sympathetic action is, like the expression of pain in the face, coming from the brain’s reaction to the pain and is going to be a secondary action.

This is where thought comes back into the equation since we still need to see that a reflex response is followed up with a sense of the character’s reaction to the hurt and that the reaction is a function of his personality. So it might be that the big, tough gangster character still reacts reflexively when he touches the muzzle of his still hot gun but that, perhaps due to a higher pain threshold, the reaction is not so great as we might expect, and particularly, he will minimize his secondary reaction to the actual pain. In pulling in the reflex or holding down any secondary action that might normally follow it, he could be trying to show that he is a hard man or make sure that he doesn’t lose status in the eyes of those around him.

In fact there is a scene of exactly this sort in Lawrence of Arabia directed by David Lean (UK, Columbia Pictures, 1962), where screenwriter Robert Bolt establishes the plot and theme of the movie and the character of T. E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) in an early scene. Set during the First World War in the Arabian Peninsula where the British are fighting the Germany’s Turkish allies, Lawrence, one of the few Englishmen who can understand the region, is sidelined making maps, until the call comes to send him into the desert to recruit the Bedouin tribes. In the map room, he snuffs out a match by pinching it slowly without any sign of a painful reaction. When a corporal tries it and reflexively starts from the pain, the corporal indignantly declares that “It damn well ‘urts.” and wants to know the trick. The trick, Lawrence tells him, “is not minding if it hurts.”

Lawrence’s ability to overcome the reflex response and the pain that accompanies the burn is indicative of his willpower, a will that allows him to accomplish great feats and, incidentally, shows off the exhibitionist and, possibly, masochistic side of his character.

As an aside, I remember contributors to the letters page of Action Comics, in issues I had as a boy, spending much time debating whether Superman could actually feel anything at all if he was the “Man of Steel” and if this meant he couldn’t react to anything. If you want to pursue this line, the question has lots of implications for action and character. How would Superman, in his Clark Kent disguise, notice that he’d put his hand down on a hotplate if he couldn’t feel anything? I imagine that his super-speed could be used to create the impression of a reflex before anybody noticed he hadn’t had one, as long as he had some way of finding out that he was overheating. The answer that the letters editor came up with was that the nerves that control pain reactions were different to the ones that detect pleasurable sensations and therefore he could have one and be able to kiss Lois without pushing his face through hers, and not the other, so he didn’t feel the impact of the bullets the hoods were firing at him.

We often deal with extraordinary characters in animation and, certainly for me, part of the fun comes in working out how the differences in their construction or abilities impact on the performances they give.

Of course, when dealing with humor, the reflex reaction is often superseded by the needs of the gag and a character will often touch a hot surface and fail to react for a beat or stand on a nail and build up a head of steam before blowing his top.

The exaggerated take that we so love in the Warner and MGM cartoons and, in later years, cartoons like Ren and Stimpy look very much like reflex reactions due to the speed at which they take place, but they are, in fact, the opposite. There is always a quantity of thought going on in these reactions because it is funnier to see the moment of stillness before the reaction that makes the reaction stronger by its presence.

The great progenitor of the extreme cartoon “take” and the kind of physical gag that causes a character to fly to pieces or squash into a cube is, of course, Tex Avery and his playful manhandling of cartoon conventions takes performance into areas of lunacy that have rarely been equaled. As we noted in Chapter 2, “Types of Performance” the heroes of Avery’s films become the very signs of the emotions they are displaying and this type of humor is a perennial favorite of the animator who likes to really take things to extremes.

The question of how far this can go and how many of the basic principles of animation we have to conform to is an interesting one. For some, there are no limits to what can be done and the character’s body can change in any way, for others there has to be something that remains constant to give the character what Chuck Jones calls “anatomy.” I don’t want to be dogmatic on this issue, but it does seem as if the character stops being a character unless it retains at least one element we can recognize, which, in most cases, will be mass. Notice how, no matter how extreme the distortion of form gets, a character in one of these extreme takes will retain its body mass so that it may stretch out but it will get very thin at the same time. The particular physics of the cartoon will change the nature of the body’s materials so that it obeys the laws that might apply to rubber rather than flesh. The secret is that, once you have chosen the kind of laws under which your creation will work, you have to stick to them. Even John Kricfalusi, who likes to push things as far as he can, is convinced of the benefit of an “internal logic” for characters and the importance of learning the fundamentals of animation so that you can then use “controlled abstraction rather than arbitrary unbalanced distortion.”

Reflex actions are a result of external force acting on the body and represent the body’s non-intentional ways of dealing with them. In the case of the hot iron or the sharp stone, the character will recoil or step off the stone, but what about those cases in which the body’s reactions can have no real bearing on the force ranged against it? I’m thinking here of the larger, more powerful actions of a tidal wave or an explosion where it isn’t possible for the character’s reactions to have any effect on the force that overwhelms him. In animation, this is as much a matter of performance as any other character actions, and the way the way the body moves has to be animated just as well as if the character were standing talking. In live action too, many of these moves have an acted component; after all, nobody is really getting shot in all those crime movies. The difference is that many of the things we see are really happening or there is a physical trick being employed to make things look real, for example, when a tank of water is emptied into the set to simulate the ship sinking or a rope is tied to a harness worn by the performer so that he can be pulled off his feet when apparently hit by bullets. In these cases, there isn’t much acting needed, in fact the bullet and rope trick is done so that the performer doesn’t have to act being hit by bullets, which would require him to push himself off the ground using his leg muscles and would look rather fake.

Until recently, we didn’t have any outside forces we could apply to a character to, for example, knock her off her feet or sweep her away in a tsunami. In CG animation, it is now possible to apply dynamic forces to the body of a virtual actor that will then act in the same way as a real body. After that the animator can take over and add the touches of acting that might happen after the initial wave had hit. From being thrown off her feet and pushed along in a realistic way, the animator can then have the character start to try to bring her motion under control or, if that is what the story needs, to have her start to panic and thrash around. The performance in the early stages is under the control of the computer but can obviously be tweaked by the animator to create the best possible effect.

In other types of animation, it is still the case that we have to animate these things in the same way we have to animate characters talking or walking around, and we have to judge the best way to create a real feeling of the irresistible force that hits them.

What is happening in all these cases, whether created by the animator or some software, is that a character that, in acting terms, is playing an action, is hit by a force that overwhelms them and stops that action. So it can be someone standing chatting in the street who is hit by a sniper or a person running from the approaching tidal wave, but there is a change that negates what has gone before. What remains is still performance but of a different kind since it doesn’t include what we might think of as acting; it is much more to do with elemental physical forces acting on a person rather than a person acting on the world. What remains in this scenario is the character’s body and the way it is designed; it may lose a sense of its weight under water but its mass and the way its limbs are connected will remain. Or, being hit by a bullet, it may lose the power to stand but it will retain the weight that will carry it to the ground. This is also partly the case where a character is being thrown around in a moving vehicle. There will be an involuntary component to the motion as the body is jolted about and a voluntary one as the character tries to keep on an even keel.

As ever, the important thing is to understand your character not, in this case, from a psychological point of view but from a physical one. You need to fully understand how she is constructed, how flexible she is, how heavy she is, in order to know what will happen to her when she encounters the external force.

Understanding the character’s physical construction is also important when looking at that other order of involuntary actions, ones that come from inside the body, like sneezing or shivering. We all know how hard it is to prevent a sneeze that wants to get out or how short a warning we get when one is about to occur; it’s like something else has taken over part of our body and, though we can reach for a handkerchief, we aren’t going to be able to stop it. Sneezes can be extremely violent and can really shake the body around, which is where the necessity of understanding construction comes in, as they can be like an explosion that sends out a shock wave from the center of the body into the extremities, with lots of secondary actions happening in the arms and legs. A thin character can look like he is about to fly apart in a violent sneeze but an obese character sneezing could look like the shock waves of an earthquake were rippling through his flesh.

For comedy purposes, the sneeze is goldmine and we’ve often seen a character hiding behind a crate in a dusty warehouse as he spies on the bad guy, trying in vain to hold back a sneeze, but we could also consider how the way a character sneezes can be funny. If the demure little old lady has a sneeze that could knock over an elephant, or the muscular heavy has the daintiest of sneezes (and a tiny pocket handkerchief), we can get a lot of amusement out of the contrast. Once again, the way in which a character copes with an involuntary action can tell us a lot about who they are.