Building both organizational and employee capability will be of paramount importance for decades to come. Organizations need to deal with the many challenges caused by rapidly changing technology, the onslaught of exiting Baby Boomers, and the generational differences from the new type of workers who will be replacing them. The unprecedented financial downturn that began in 2008 will compound the problems facing an organization’s ability to build capability as companies downsize and restructure their operations. Reaction to market downturn will displace some employees, particularly those in maturing economies, but will create opportunities for those who remain within the organization.

Expanding work beyond country borders is also creating challenges and opportunities. Mercer Human Resource Consulting says, “The globalization of the labor market has brought a new core competency to the table—the ability to work comfortably across languages, cultures, and time zones. People with these skills will be in great demand and will expect different career paths than what many organizations are accustomed to providing.”1

These changes have contributed to a shorter lifespan for the skills needed in organizations and an increased need for global integration. Through interviews with 1,130 CEOs, general managers, and senior public sector and business leaders worldwide in 40 countries, the 2008 IBM Global CEO Study reveals that while CEOs are anticipating becoming more globally integrated, managing talent worldwide will be a key dependency on how effectively their organizations can achieve such goals. CEOs are focused on making changes to take advantage of global integration in a variety of ways, including entering new markets, expanding their brands and products, and optimizing their operations on a more global scale. The most prominent change cited, however, is that “57 percent of CEOs intend to change their mix of skills, capabilities, and knowledge assets around the globe.”2 The IBM Global CEO Study also says that senior HR executives are concerned about finding new talent pools and updating employee skills.3

Companies need to understand how all these changes impact their ability to build and retain organizational capability. It will become increasingly important for companies to focus on ensuring that employees grow their skills in order to meet new challenges that the organization may face as the economy recovers and new business models emerge.

According to an article written by Mike Brennan and Andrew Gebavi in the March 2008 issue of Chief Learning Officer Magazine, a survey conducted by NYU’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies in 2006 showed that New York professionals of today expect to change careers more often than workers of prior generations. The idea of a lifelong career is a fading reality for a variety of reasons including a lack of defined pension plans, longer life spans, and technologies that allow employees to be more self-directed in their career exploration. It, therefore, becomes necessary for organizations to provide a flexible work environment where employees can make informed decisions to manage their careers.4

Companies that make the most of their global workforce take a holistic approach to managing their talent. They start with a comprehensive understanding of existing workforce demographics and capabilities and develop the ability to evaluate the current and future supply and demand for critical positions. Further, they are able to target their recruiting efforts to fill existing and potential future gaps for key job families, as well as create formal and informal development opportunities for employees whom the organization would like to retain. Global organizations that focus on talent management also apply tools and processes to connect individuals and locate expertise worldwide. Surrounding all of these efforts is an overall performance management system that is designed to provide employees with clear direction and the feedback necessary to improve their performance.5

To respond to these changing dynamics, organizations need to create agile career development processes that are flexible enough to build deep organizational capability. They also need to provide careers for employees in a way that builds individual capability. We now discuss how to develop organizational and individual capability by enabling employees to achieve meaningful careers that support the company in achieving its goal.

The key to building organizational capability begins with building individual employee capability. Employees need to focus on growing existing skills, as well as on learning new ones. They also need to gain the appropriate experiences that can help them grow their individual capabilities to match those needed by the organization to serve clients or customers. They need to understand emerging job roles and what skills are required to fill those roles—and ensure they take appropriate action to progress in their careers. They need to take even more responsibility for their own career development and managing their careers based on both the needs of the organization and their own personal aspirations. The combination of these factors will force organizations and their employees to collaborate on balancing what the company needs from its employees with what employees want from their careers.

This requires providing the appropriate structure, tools, resources, and support for employees to progress in their careers. In Chapter 3, “Defining the Career Development Process,” Figure 3.1 depicts the three elements that contributed to building meaningful careers: personal goals and aspirations; company business strategy and goals; and career opportunities in the company. At the core of these elements is the partnership that needs to be forged between the organization, the manager, and the employee. We now explore how these three elements work in tandem to provide the basis for career paths that lead to building both employee, and ultimately organizational capability. In Chapter 7, “Creating Meaningful Development Plans,” we explore the importance of the partnership among the organization, the manager, and the employee in the career development process.

Career paths of tomorrow have begun to take different shapes than the career paths of yesterday. This can be seen today by looking at the differences in how the Generation X or Y individuals view work versus their predecessors, the Baby Boomers. In recent years, loyalty to any particular company has become a thing of the past, and today’s young worker has different needs than the worker of yesterday. For instance, according to the Selection Forecast 2006–2007 cosponsored by Development Dimensions International (DDI) and Monster, responses from over 5,600 staffing directors, hiring managers, and job seekers in five global regions reveal that young employees want a fun place to work with social networks, whereas older employees moved up the ladder in a particular career and often stayed with the same company for their entire career. Employers need to be aware of these differences in order to attract younger employees’ interest.6

Thus, companies need to understand the needs of their younger emerging workforce and craft career paths that energize such workers, rather than offer them no option but to leave prematurely.

At IBM, its Expertise Management System and career framework, first introduced in Chapter 2, “Enabling Career Advancement,” provide the infrastructure that shapes career paths for IBM employees. Career paths are flexible enough to meet both personal and corporate goals as workforce needs change. The next section provides a view of IBM’s approach to building careers that is enabled through its agile career development process. We begin with a description of how job roles and associated career paths are defined within the company and form the basis of the Expertise Management System. We then describe how IBM’s career framework will provide an avenue for people to advance in their career over time.

As a company defines and changes its strategy, it is important to define and update the types of job roles and associated skills that are required in order to build organizational capability to achieve organizational goals. Employees need a guide for how they acquire the appropriate training and experiences required to progress in their careers while keeping up with these changing demands. This type of guide is often referred to as a career path or a map.

According to BNET Business Dictionary, the business definition of a career path is “a planned, logical progression of jobs within one or more professions throughout working life. A career path can be planned with greater assurance in market conditions of stability and little change.”7 However, in times where market conditions falter and layoffs are inevitable, employees need to stay abreast of their options based on the skills they possess. Whether employees are indeed laid off or whether they are among those who remain within the organization, they need to be flexible. They may need to be prepared to change “gears.” What was a thriving career yesterday could diminish or even vanish tomorrow as jobs require totally different skills than in the past, or technologies change and certain job roles become obsolete.

Employees also need to continually re-assess where they are in their personal career journeys. What they need and desire at the age of 22 may be different at the age of 30 or 40 or beyond. An agile career development process can also help employees manage their careers through both good and turbulent times. The process should include guidance to employees and managers on how to develop meaningful career paths. A career path enables employees to advance in ways that are meaningful to them personally. It also provides a structure for the organization to show employees how they can acquire different skills, gain valuable experiences within one job role or through various job roles, and build capabilities that provide value to clients. While employees need to take responsibility for owning their own career paths, managers also play an integral role in helping employees plan their career paths based on employee desires and what the organization needs from its employees.

If the 1980s was the era of the generalist, and the 1990s was the era of the specialist, then we are now in the era of the versatilist. In today’s business arena, technical aptitude (or any single specialty) alone may not always be sufficient. “Versatilist” is the term used to describe people whose widening portfolios of roles, knowledge, insight, context, and experiences can be applied and recombined in numerous ways to fuel innovative business value. According to Wikipedia.com, “A versatilist is someone who can be a specialist for a particular discipline, while at the same time be able to change to [or perform] another role with the same ease.”8

Employees need to be more versatile in what they know in order to compete for jobs and to remain resilient in an environment where technology and advancements in products and services change at lightning speed.

Career paths can take either a traditional approach or a versatile approach. In Chapter 2, we introduced the concept of multiple career paths. To further expand upon those concepts, on the traditional path, employees move forward by moving upward, gaining responsibility and authority in a single field. At IBM, many job categories offer focused paths for an employee’s career in a particular area of specialty. Employees may spend their entire careers in one particular primary job category, such as a software developer or human resources. They progress up the career ladder by having different jobs and experiences within their discipline, or they move between business units and gain exposure to other parts of the business. They build deep levels of expertise in their areas of specialty and are considered experts in this field.

In addition to the traditional path, IBM also offers a career path to meet the growing need for employees who are versatile, making lateral moves while expanding their skills in a career path that might span multiple job categories. According to an internal IBM website called “Advance your career,” “Employees move from one field to another, responding to their own interests and the company’s changing needs. They apply existing skills in new ways, share experience with colleagues, and broaden their competencies. Their rise through the hierarchy might seem slower, but they can reach positions with broader influence across departments and business units.”9 Versatile employees may be deep experts in multiple areas, although it may take years to acquire this level of in-depth expertise across several disciplines. In what is the more common scenario, employees are very well-rounded in multiple areas of the business but are not necessarily considered a thought leader in any one particular discipline. Employees with these types of versatile skills are becoming more popular across IBM as the complexity and global nature of the job roles increase. This situation is particularly prevalent in countries where there are large numbers of both employees and clients and where the complexity of client solutions may be greater. In contrast, many IBM employees are already versatilists, especially those in countries where there is a more limited client base and the IBM population is smaller, which requires each individual employee to perform multiple job roles in order to get the work done.

Both types of employees continue to be needed in IBM in response to client needs. The particular path that employees choose depends upon their individual needs as well as the overall needs of the company and where specific job roles are required. The company still requires employees with deep expertise in a particular discipline to solve very complex client problems. There is also an emerging need for employees who possess a wide range of capabilities so they can approach client opportunities in a more holistic manner.

A similar example is the case of a physician. Specialists are needed for very complex medical issues, where deep expertise can help quickly pinpoint a patient’s diagnosis and treatment options. The specialist, such as a medical oncologist that treats cancer patients, has treated the same type of cancer many times in many patients and often has the latest state-of-the art testing equipment or access to in-depth research and advanced treatments. On the other hand, that same patient may need a primary care physician as well to treat other minor illnesses such as a sore throat or a cold, where the expense and expertise of a specialist is just not required. Internists often treat more than just the sore throat; they may also realize that the patient has a family that is susceptible to catching the illness from the patient and hence speaks to the patient about how to protect his or her family from catching a cold. The primary care physician approaches the treatment in a very holistic fashion and knows when to refer the patient to a specialist.

In addition to versatility, employees at IBM can pursue a professional/technical career path in which individuals carry out work, utilizing an area of expertise. Some employees also go on to pursue managerial job roles in which individuals carry out work through leveraging the skills and knowledge of others. In the latter case where a technical career path leads to a managerial job role, the manager often retains his technical expertise at some level of mastery, however, now also focuses on growing “people management” skills.

All of these types of career paths can lead to an executive career path, whereby individuals develop the company’s long-term needs and strategies and provide leadership in executing them. But what guides employees? How do they determine the best way to progress along any particular path or even which path to choose?

The next section talks about how to define job roles as the basis for career paths. It shows how IBM creates flexible career paths that meet employee expectations and help achieve company talent goals.

Employees typically begin work in a company in some “job role”—or what they’ll be responsible for every day. Employees may also change job roles over time, whether it’s within the same organization or a new organization. Job roles are an integral part of a person’s career path.

At IBM, a job role is defined as a named, integrated cluster of work responsibilities and activities that need to be performed by a single person. In many cases, a single job role constitutes most of a person’s responsibilities and activities. Job roles are the levels at which skilled resources can be planned, acquired, developed, and deployed, and they need to be kept to a manageable number so that the marketplace can identify easily with all of them. According to an IBM’s internal Expertise Taxonomy website, “Job roles are important because they precisely define skills and ability to perform work independently or in teams. They are the skills ‘DNA’; that is, they are the fundamentals that keep the people side of the...business running.”10 With job roles, IBM has a common language for recruiting, skills development, and serving the client.

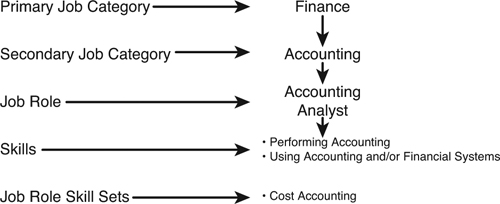

Chapter 5, “Assessing Levels of Expertise and Taking Action to Drive Business Success,” provided an overview of the IBM Expertise Management System, which begins with the definition of a common and consistent taxonomy for job roles and skills all across IBM. It starts by defining primary job categories and additional secondary job categories that comprise all the job roles needed across the company. Each IBM employee is in a single job category at any point in time. This is defined by the work the employee performs and the employee’s position code (a unique code used for compensation purposes and is determined based on the type of work one does and the level of responsibility for that job). Job categories are global and are composed of two groupings: the primary and secondary job category.

The primary job category characterizes broad segmentations of the type of work employees perform. These categories are wide-ranging in scope. All employees are assigned to a job category based on position code.

The secondary job category identifies more specific types of work that employees may perform and are subsets of the primary job categories. These categories are narrower in scope and are used within IBM to identify significant populations deemed necessary for business planning purposes. For instance, finance is a primary job category. Its secondary job categories are accounting, audit, business controls, other finance, planning/pricing, and tax and treasury.11

The term “career” is often used instead of job category. Each IBM employee worldwide performs one or more job roles and may have many job role skill sets, all with associated skills and descriptions. A job role skill set is a specialization of one and only one job role. These titles describe what one does: what a person’s job is.

The number of IBM’s primary and secondary job categories and associated job roles may expand or contract over time as changes in the business dictate a need for more or fewer job roles. Each employee is in a particular job role, depending both on the skills and experiences that employee possesses and the needs of the business. How long a given employee stays in a particular job role or moves to other job roles depends on a variety of factors, and it is this movement that to a person’s career path.

The relationships among the various components of IBM’s expertise taxonomy are illustrated in Figure 6.1. In this example, the primary job category is finance.

To illustrate how this works, let’s go into more depth with the associated secondary job category of accounting. According to the definition within IBM’s expertise taxonomy, “Accounting is responsible for recording, analyzing, and reporting worldwide financial data in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), in support of IBM’s legally required filings.”12 An example of a job role associated with this job category is accounting analyst. The taxonomy continues to explain that

Two examples of associated skills include performing accounting and using accounting and/or financial systems, and one example of the various job role skill sets is cost accounting.

Developing a formal structure such as the preceding example of IBM’s expertise taxonomy provides a solid foundation for employee careers by providing employees a view of the types of job roles available, the skills required to perform those job roles, possible careers within the company, and the career(s) to which these job roles can lead. Developing a career path based on such components helps employees seek the appropriate job roles and experiences needed over the course of time to achieve personal aspirations and build capabilities that clients value. As employees across the company develop skills and gain new experiences, they build individual capability needed to serve the client. Over time, this collective growth in expertise helps the organization gain strength and increases its ability to meet client demands.

IBM provides guidance for the career paths, which typically contains a variety of elements that are critical in helping an employee progress along a path, build skills, gain new experiences, and advance in their careers. Career paths however, are not prescriptive. They provide career guidance for employees, and in some cases, the paths provide required steps that must be taken in order to achieve a particular career goal. In other cases, the guidance is suggestive, and various options are provided depending on the particular employee need. At times, employees may have to take a detour on their career paths, either because they choose to or because business conditions warrant such changes. Hence, employees need to be flexible in their career progression. They need to realize that not any two people’s career paths will look identical and that the best laid plans sometimes need to change. Because career planning is personalized and unique to the individual, the organization’s career development process needs to be nimble enough to allow for individual differences and changes in the environment.

Managers at IBM are very involved in helping employees lay out career paths as part of the overall career development process. Managers provide guidance in using various tools to build paths that suit the employees’ needs as well as meet IBM’s goal of having the appropriate capabilities required to serve its clients.

As already noted, career paths are unique to the individual, and they are customized as part of a career development discussion that managers have with employees. For this to work smoothly, IBM provides guidance to both employees and managers that assist them in developing a personalized plan for a particular career path. The various elements of the guidance that is provided by job category for a typical career path at IBM are explained next. This guidance might be obtained via a portal on the internal company intranet and is available to all employees and managers. It should be noted that the outline that follows is typical; depending on the job role, some career paths are more or less complex than others and therefore require more or less guidance. In addition, while this is how IBM handles career paths, this approach to providing career guidance could apply in many different types of organizations.

Following is an example of career guidance14 that IBM provides to its employees; it is typically provided for a particular job category.

- The description of the job category—This description could include information that describes the various roles within the job category and their responsibilities, characteristics of the type of person who would succeed in these types of job roles, and any unique traits or areas of specialty that can help individuals distinguish their areas of specific expertise.

- The positions within the career path—Employees can move along an upward career “ladder,” whereby they remain within the same job category while moving from one level to the next. An example would be a new employee at an entry-level position who, after some amount of time and experience, gets a promotion and moves to the next level or grade within the job category.

- The job roles within each career path—At IBM, a variety of job roles are contained within a job category. Therefore it’s important for employees to understand what job roles are available to them within any particular job category. Often skills are transferable across job roles within a job category, which creates another avenue for employees who do not desire to “move up the ladder” in a traditional sense, but want broader experiences in a variety of areas. To this end, the career guidance includes a listing and description of the various job roles within that particular career path.

- The associated expertise—The guidance should contain a listing and description of the required skills needed to perform the job roles that lead to growing one’s expertise.

- Learning activities—Because employees will need to grow their expertise, they need to understand what specific learning activities will help them achieve their career goals. The career guidance includes recommendations of such activities. These activities could include formal classroom or e-learning training or could be more experiential in nature, where learning takes place on the job through mentoring, job shadowing, or other collaborative endeavors.

- Specialties—Many categories within IBM job roles have “specialties,” requiring specialized skills in one or more areas of IBM’s business. One example would be a salesperson specializing in selling IBM solutions to companies in a particular industry. The salesperson would be required to grow a level of capability in the specific industry they serve as a way to better serve the client.

- Certifications—Some job roles have certification requirements and/or options. The certification is often associated with an external industry group or organization. Any necessary certifications, along with the requirements for achieving them, are included in the career guidance for a given career path.

- Collaboration—Connecting with others in the company is an excellent way to build a career and explore options. IBM offers employees a variety of outlets for building community and connecting with others, both within and outside a job category. Some of these avenues include participation in external activities, such as industry conferences and events, joining professional societies or associations, using social network tools, and finding a mentor. (Mentoring is explored in depth in Chapter 8, “Linking Collaborative Learning Activities to Development Plans”).

- Communities—IBM has also established “communities” to help employees collaborate with each other to learn and grow. There are several kinds of communities, from formal “communities of practice” to informal communities of similar interest. Communities of practice are supported by the business and include subject matter experts who are available to the members of the community for guidance, informal mentoring, and formal community learning processes. The communities are bound by the members’ commitment to give back to the community as well as benefit from it. The communities also promote an environment for exploring new ideas through a commitment to building trust and social capital.15

- Success stories—Success stories are examples from employees throughout IBM that provide interesting and varied approaches to career success. The stories might inspire other employees to think about how they can build their unique career success stories. While each career path is individual, exploring these success stories is often a great place to start, particularly if employees are contemplating a career move.

- Miscellaneous job role information—In addition to the preceding elements, IBM also provides miscellaneous information to help employees select their next career steps. This information is particularly useful as employees become more versatile and move across job roles in different parts of the business to gain additional expertise. It is also useful if employees are interested in changing careers. This information includes

• Common career moves across the company—IBM provides information that shows where employees can leverage particular skills in different job roles. For instance, employees who are consultants sometimes move into project management job roles, given that many of the consulting skills used in managing large engagements are transferable to project management roles. Knowing this type of information helps employees to better understand the possibilities available to them.

• Job role populations—This listing shows the approximate number of employees who are in a particular job role and includes growth across those populations. This information helps employees determine where there is either job role growth or retrenchment.

• Job categories by business unit—This is a view of the different types of job categories that are often found in particular business units. The information provides the relative worldwide breakdown, by organization, of IBM employees in each job category. It provides some guidance on where certain positions and job categories might be more prevalent and also helps employees see how they can move across the business within their job roles while gaining new experiences in different parts of the business. For instance, salespeople are found mostly in IBM’s “Sales and Distribution” business unit. Here, client relationship professionals work with integrated teams of consultants, product specialists, and delivery fulfillment teams to improve clients’ business performance. These teams deliver value by understanding the client’s business and needs. They then bring together capabilities from across IBM and an extensive network of business partners to develop and implement solutions for clients.16 However, sellers can also be found in IBM’s “Software Group” business unit. These employees focus on the sale of software for primarily middleware and operating systems.

In a large company such as IBM, it is particularly important that the career development process be flexible enough to both respond quickly to changes in the environment and also to offer employees the best options for advancing their careers. According to the 2008 IBM Annual Report, IBM had 398,455 employees and did business in more than 170 countries,17 so the variety of job opportunities is vast. It can be very confusing for employees to navigate across multiple business units and even countries in seeking career opportunities. Without some form of guidance, employees are not always sure of what their potential is across the company. The career guidance described in the earlier section of this chapter provides insights into how a company can provide clarity to employees on the options available to them. But how do employees put all this information into action? How do they determine what the next step is if the options are abundant?

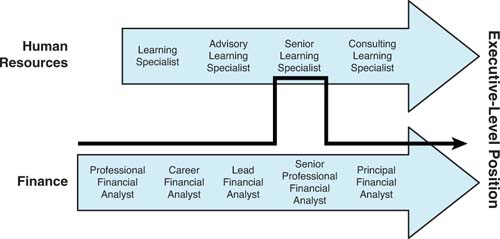

This guidance can be used to identify the options available as part of a career path for an employee. For instance, according to the IBM internal website called “Advance your career,” Figure 6.2 provides an example of a typical career path for employees in both human resources (HR) and finance.

Employees can spend their careers in a linear path. For instance, let’s take an employee, Jane Doe. She’s in Finance and starts out in an entry position as a Professional Financial Analyst. Jane can move across multiple job roles and levels of responsibility within finance. However, at some point, Jane may desire a change whereby she becomes more versatile in how she applies her finance skills and decides to move into an HR job role. Another situation may be that HR may have a need for someone with a finance background and seek individuals for HR job roles.

In this example, Jane became very versed at mentoring and coaching new financial analysts. While doing this, Jane acquired good facilitation skills through this on-the-job training. At one point in her career, the Learning team was looking for a facilitator to teach accounting classes as part of the finance curriculum. Jane found that she really like teaching, hence she spoke with her manager about doing an assignment in Learning as a facilitator. She then worked with her manager on selecting some courses and other possible work experiences to hone her facilitation skills.

After some period of time, a Learning Facilitator job role became available. The Learning team in HR was expanding their curriculum to include a Business Acumen class for technical (non-finance) employees. This would address a need for engineers and other technical employees to better understand the business dynamics of running the organization. HR then posted the Learning Facilitator job role on the internal job posting system. The skills required included not only facilitation skills but subject matter expertise in finance needed to teach basic and an advanced Business Acumen classes. Jane applied for this internal position and was offered the job. Her expertise in finance was a major factor in the decision, in addition to her versatility in acquiring facilitation skills.

Jane could continue in this job role for a long period of time and even advance to a higher level within HR. This could be construed as a career change if Jane decides to spend her remaining tenure in HR. She could also decide to move back to finance after she gained adequate capability in HR. Should she decide to return to finance, she would now have a broader perspective of the operations of the business and would bring these newly acquired skills back to her role in finance. If she were to remain within HR, she could further expand her facilitation skills or even move into a different learning role, such as an instructional designer who actually develops learning activities. These types of moves benefit employees by providing versatility in their careers and increasing the capabilities they personally bring to the table. It also benefits the company by ensuring its employees have the breadth and depth often needed to manage operations in a complex environment.

The example given here provides insight into how a person’s career path can have “twists and turns” over time that can even lead to a different career. The employee needs to work closely with her manager to determine whether such a career move is possible and what steps need to be taken to enable such a change. Once it is determined that moving to an HR role is feasible—based on both employee desire and business need—the employee and manager develop a plan that can help the employee achieve her new career goals.

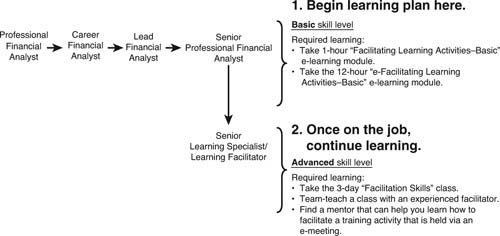

The following sidebar19 provides an example of career guidance that should be considered as Jane thinks about a potential career change.

Figure 6.3 provides an example of what Jane’s career path might look like after she made the decision to hone her facilitation skills to compete for a job in HR. She will then need to continue growing her skills in this new role. While this example is based on IBM’s career path for a Learning Facilitator, this information is fairly generic and could be applicable to many organizations. Jane needs to enter the career path here based on her level; hence, she needs a customized career path to increase her skills to be competitive for the Senior Learning Specialist level while she is still in the finance job role.

In Chapter 2, we introduced the concept of a career framework. At the time of this writing, IBM has begun the phased deployment of the framework to employees in several targeted primary job categories, with a goal to expand it to all job categories in the coming year. The career framework is another dimension of the Expertise Management System and identifies the capabilities that employees need in order to provide value to their clients. While skills are needed for an employee’s job role today and are acquired through targeted learning activities and repetitive practice, they tend to be learned in a short period of time. Capabilities on the other hand are acquired throughout one’s career and could take years of different experiences in various job roles to develop high levels of capability. The career framework provides a long-term focus on career development within IBM and provides the breadth and depth needed to grow capabilities that clients value.

The following section expands upon this discussion and shows how the career framework will further assist employees in understanding what career options are available to them and how they can advance in their careers.

IBM’s new career framework, when deployed, will allow employees and managers to further define clear, progressive career paths that may follow a single job category (for example, sales) or span multiple job categories (consulting and sales, as an example). This will result in building deep levels of capability and developing more versatile employees. It expands upon the components of the expertise management system that are in place today by enabling employees in any job role to understand what capabilities clients value and how they can grow those capabilities as part of their career advancement. The career framework consists of several major components, including capabilities that employees need and are valued by IBM’s clients, an organization structured to support the new framework, and enhanced online web-based IT tools and career resources. As a part of its implementation, it will be incorporated into the career development process that we’ve highlighted throughout this book.

The career framework is currently composed of client-valued capabilities that were identified as part of a year-long analysis, focused on the client experience. The capabilities include selling, consulting, and providing industry insight, among others. More capabilities may be added to the framework as the work is expanded to include other job categories. There are many benefits to this new framework.

Employees will gain clarity in understanding capabilities (core skills that can be leveraged) needed for current and future roles. They will be able to identify new career possibilities that leverage their current capabilities and receive guidance on developing capabilities needed to succeed. Employees will be more effectively able to define for IBM what they are able to do, and to be possibly chosen for potential deployment to new opportunities. Finally, employees will benefit from more substantive employee/manager career development discussions.

Managers will also benefit from the new framework. They will better understand the capabilities of each member of their teams and gain greater precision in matching employee capabilities and successful client experiences to emerging opportunities. They will also be able to lead more substantive development discussions with employees.

The following processes underlie the career framework, along with associated web-based tooling and a new, dedicated, website that also contains complete details on the initial capabilities and how they are used to drive client success.

There is a new validation process that guides employees on how to progress within the framework over time by successfully demonstrating in a sustained fashion the requirements for a capability at a specific level of expertise. There are five levels of capability, from “Entry” to “Thought Leader.” Employees will be placed into the framework based on a set of criteria that includes their job roles, levels or grades, prior experiences, and other related criteria. They will be aligned to one or more of the initial capabilities, with a “major” and one or more “minors.” For instance, a sales person would be aligned to the “selling” capability as his “major,” similar to a college student who majors in a particular subject area. These are the skills and experiences needed as part of what they do on a day-in, day-out basis. In addition, a sales person might also require some level of capability in understanding the industry in which they sell products or services, hence he would also be aligned to the “providing industry insight” capability but possibly at a lower level of mastery than his “major.” Again, this is similar to college students who may minor in a particular subject area and take some courses in such so they have general knowledge, but it is not their major area of study. Together both subject areas provide a well-rounded student, and in the case of the career framework, provides a well-rounded employee.

The validation process is supported by web-based tooling, which allows an employee to apply for a move from one level of capability to the next. Achieving this next level of capability is a major milestone in one’s career and could take several years of building skills, changing job roles, and gaining different experiences. Hence the validation process provides an additional aid in developing a career path for an employee, in addition to the guidance described earlier for a specific job role.

The career framework will also showcase a career advisor network, a new peer-to-peer learning initiative, where “volunteer employees” have been trained in IBM’s career development process and will answer questions for employees being introduced to the career framework for the first time. They will be able to provide guidance via an electronic chat session on the various components of the career framework and how it can be used to help the individual employee.

A gap analysis is another lever available to employees. It shows how employees can use the framework to assist them with their career development; comparing their personal suite of capability levels with the recommended levels for key job roles across IBM. Based on the outcome of this analysis, employees can build different learning activities and required experiences into their development plans based on a “Career Guide” that has been provided to employees. This additional information provides yet another view of how one can progress in their career along a particular career path, and provides milestones along that path that recognizes their level of expertise and career achievements.

It is important to note that while a career path may have some standard items that are common to many employees, such as learning activities that help grow certain skills, career paths can be very individual based on the skills that the employee brings to the table. An employee will need to work with her manager and/or mentor to develop a customized plan. Chapter 7 provides further insights into how employees and managers engage in developing customized career paths through an individual development planning process. We discuss in detail how IBM approaches career development planning as part of its career development process. Career development planning provides an avenue for employees to work with their managers and mentors on carving out career paths that meet individual needs and allows employees to take responsibility for their own careers by using the plethora of career guidance provided by the company. Chapter 8 then focuses on mentoring relationships and other collaborative ways to learn that can enhance a person’s career path.

One of IBM’s primary job categories includes management. Most IBM managers begin their careers in one of the other primary job categories. As employees progress in their careers, they have the option to remain in a “nonmanager” role and in some cases can progress to the executive level in a technical role. In other instances, employees might choose a manager job role whereby the manager supervises other employees or managers (as in the case of an “up-line” or middle manager) and accomplish work through others. Employees that choose a manager career path often move in and out of the manager role and go back to their former careers—or choose new ones. As they gain new experiences, they may move back into management roles. Other employees fulfill their careers as managers. They might also move into manager roles in other parts of the business for variety and to gain new experiences. These various career paths are determined by a combination of employee desire and company need. Manager roles can also lead to executive positions if the individual is qualified for such a role and if a need exists.

Various learning programs exist in IBM for first-line managers, up-line or middle managers, and executives, as well as “emerging leaders” or those individuals identified as future leaders or managers in the company. As part of IBM’s talent management process to fill and grow the executive ranks, the company is in the process of redesigning its business and technical leadership program that provides a single view of its global leadership pipeline. The program is intended to identify, develop, and retain high-potential, high-performing personnel to ensure IBM has the right leadership in the future. This is accomplished through targeted leadership and business acumen development that helps IBM’s future leaders grow and realize their full potential. IBM has created a common and global set of guidelines for the identification and development of its future leadership and at the time of this writing, is currently redesigning the program to reflect the needs of tomorrow’s succession planning and leadership pipeline.

These programs help employees move from their technical roles to manager roles, and once in the manager roles, they learn how to be high-performing managers.

Companies should consider implementing a formal structure that identifies and defines the job roles needed within the company, as well as the associated skills needed to perform those job roles, in order to attract, retain, and develop employees. The extent to which companies do this will be determined based on the size of the organization; however, companies of any size will benefit from some planning in this area.

Senior management must be committed to such an effort and provide ample support and resources. The following is a suggested list of critical success factors to consider in developing an expertise management system:

• Secure senior management commitment, sponsorship, and funding, within both HR and the business units.

• Identify a program owner, someone with the appropriate authority to manage the system who will be given adequate funding to secure the staff required to drive the work effort.

• Create a partnership with the lines of business across the company. They will be instrumental in identifying the types of jobs needed and developing the job roles and associated skill requirements to support the company strategy, based on their line of business mission.

• Develop the appropriate tools that might be required to house the job role descriptions, skills and definitions of such skills, and employee assessments of these skills.

• Develop a career framework that identifies the required capabilities to serve clients and provides a means for career advancement.

• Link the needed learning activities required to grow.

• Provide employees access to the right experiences that lead to career advancement by building individual capabilities that clients value.

• Identify the criteria for certifications, if required.

• Integrate career paths as part of the career development process.

• Provide the appropriate career guidance to managers and employees so they are aware of the job roles within the company, the competencies, skills, and experiences needed to build individual capability, and the options available for career advancement.

• Measure the progress of the initiative for continuous improvement.

Endnotes

1Mercer Human Resource Consulting. Point of View. “The Career Joint Venture: Forging a three-way partnership to build careers and drive business performance.” 2005. p. 5.

2IBM Corporation. “The Enterprise of the Future: Implications for the Workforce,” The IBM Global CEO Study. Last updated October 8, 2008. p. 14, http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/index.wss/ibvstudy/gbs/a1030532?cntxt=a1005263.

3Ibid, p. 14.

4Brennan, Mike and Gebavi, Andrew. “Managing Career Paths: The Role of the CLO,” Chief Learning Officer Magazine, March 2008: pp. 48–49.

5Lesser, Eric; Ringo, Tim; Blumberg, Andrea. Transforming the Workforce: Seven keys to succeeding in a globally integrated world. IBM Global Business Services: May 2007.

6Howard, Ann, Ph.D., Scott Erker, Ph.D., and Neal Bruce, “Slugging Through the War for Talent. Development Dimensions International, Inc. and Monster,” Selection Forecast 2006–2007 Executive Summary. pp. 1–3.

7BNET Business Dictionary. “Business definition for: Career Path,” http://dictionary.bnet.com/definition/career+path.html.

8Versatilist. Wikipedia.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Versatilist.

9IBM Intranet. “Advance your career” website, Updated January 26, 2009.

10IBM Intranet. Expertise Taxonomy website; “About Expertise Taxonomy.”

11Ibid.

12IBM Intranet, Expertise Taxonomy website; “Expertise Taxonomy Browser, Version M72.”

13Ibid.

14IBM Intranet. Career Guide.

15IBM Intranet. Collaboration Central: Communities.

162007 IBM Annual Report. “IBM Worldwide Organizations: Sales and Distribution Organization,” p. 21.

17IBM 2008 Annual Report. “Management Discussion: Employees and Related Workforce,” p. 1, http://www.ibm.com/annualreport/2008/md_7erw.shtml.

18IBM Intranet. “Advance your career: Broaden your career web pages,” Updated May 3, 2007.

19IBM Intranet, Expertise Taxonomy website, op. cit.

20IBM Intranet. “Facilitator Zone,” Facilitator excellence learning plan.